Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

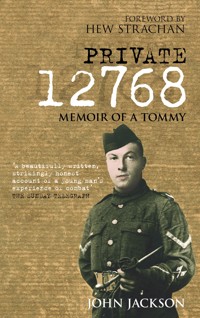

A newly discovered account of life in the trenches that challenges our perception of how British troops viewed the First World War. There is no shortage of personal accounts from the First World War. So why publish another memoir? The principal reason is the tone of enthusiasm, pride and excitement conveyed by its author, Private John Jackson. Jackson served on the Western Front from 1915 until the war's end; he was present at Loos in 1917, on the Somme in 1916, in Flanders in 1917; he was on the receiving end of the German offensive in April 1918; and he took part in the breaking of the Hindenburg Line at the end of September 1918. Conditioned by Wilfred Owen's poetry and dulled by the notions of waste and futility, British readers have become used to the idea that this was a war without purpose fought by 'lions led by donkeys'. This narrative captures another perspective, written by somebody with no obvious agenda but possessed of deep traditional loyalties - to his country, his regiment and his pals.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 406

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

John Jackson was a ‘lion’. He joined up a few weeks after the First World War was declared and served on the Western Front from 1915 until the war’s end. He was present at Loos in 1915, on the Somme in 1916 and in Flanders in 1917; he was on the receiving end of the German offensive in Flanders in April 1918, and he took part in the breaking of the Hindenburg Line at the end of September 1918, going on to march into Germany, liberating Belgium and France. What makes this memoir unique is that John Jackson doesn’t look back on his battle experiences with disillusionment, and presents a view of the war quite at odds with the all-pervasive War Poets’ bleak outlook.

This memoir was written by an ordinary Private, who saw the worst of the conflict, streets ‘strewn with dead and running with blood’, but whose belief in the just fight of the British Army and his respect for his superiors, many of whom he considered ‘the best of friends’, never wavered. His narrative captures the devotion and courage of the soldiers of the day, and his moving account leaves us in no doubt of his own sense of victory at the end of the war.

John Jackson wrote up his remarkable memoir in 1926, basing it on the diary he kept throughout the war and his vivid recollections of the conflict. It has remained unpublished until now.

JOHN JACKSON

John Jackson ‘signed on for “3 years or the duration”’ of the Great War on 8 September 1914, leaving behind his family and job with the railways. He joined the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders and was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery on the Passchendaele Ridge in 1917; by the war’s end he had been appointed a Corporal.

HEW STRACHAN

Hew Strachan is the Chichele Professor of The History of War at the University of Oxford. He is universally acknowledged as the world expert on the First World War and is author of Oxford University Press’s landmark three-volume history of the First World War, on which the recent Channel 4 series was based. A chance recommendation led to his discovery of the memoir still treasured by John Jackson’s niece, and his immediate recognition of its fresh perspective on the war.

CONTENTS

Title

Foreword by Hew Strachan

A Note on the Text

Preface

1 War!

2 I join the Cameron Highrs

3 Forming the 6th Battalion

4 Rushmoor Camp

5 Life at Bramshott

6 Billeted in Basingstoke

7 Chisledon Camp

8 Sports and a Royal Review

9 Off to the ‘Front’

10 Our journey to the trenches

11 Into the fighting line

12 The battle of Loos

13 Some trench fighting

14 15th Division in rest

15 Through hospital to ‘Blighty’

16 At Stirling

17 Back to France

18 With the 1st Camerons

19 On the Somme

20 A month’s rest

21 More of the Somme

22 Rough times in the trenches

23 Moving around

24 On the Assevilliers Front

25 Work and play

26 Northwards to Belgium

27 The Nieuport Sector

28 Clipon Camp

29 Home on leave

30 Passchendale

31 In front of Houthulst Forest

32 Decorations on the field

33 New positions at Houthulst

34 The Pigeon school

35 Langemarck Sector

36 At Givenchy and Esars

37 The defence of Bethune

38 The signalling school

39 Noeux-les-Mines

40 A holiday in Paris

41 Gassed!

42 Storming the Hindenburg Line

43 Armistice Day

44 A long, long trail

45 Marching eastwards

46 Crossing the German frontier

47 The end of the trail

48 A few weeks in Germany

49 Coming home

50 Conclusion

Afterword

Copyright

FOREWORD

There is not a shortage of personal accounts from the First World War. Most of those who fought may not have been poets, but they could read and write. The war stood on a cusp. Compulsory primary education ensured basic levels of literacy. A couple of generations later and the primacy of the written word would be challenged by other forms of communication. True, there are fewer narratives by private soldiers than by officers. But that still does not make John Jackson’s story unique. So why publish another memoir?

The principal reason is the tone of enthusiasm, pride and excitement conveyed by its author. Conditioned by Wilfred Owen’s poetry and dulled by the notions of waste and futility, British readers have become used to the idea that this was a war without purpose, fought by ‘lions led by donkeys’. John Jackson was a lion. He served on the Western Front from 1915 until the war’s end. He was present at Loos in 1915, on the Somme in 1916 and in Flanders in 1917; he was on the receiving end of the German offensive in Flanders in April 1918, and he took part in the breaking of the Hindenburg Line at the end of September 1918. For much of that time he was a regimental signaller, crawling over open ground ensuring that telephone links were maintained despite falling shells and small-arms fire. He was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery on the Passchendaele Ridge, the furthest point of the British advance in the third battle of Ypres. Those who doubt the value of decorations for gallantry, and their effects on morale, will suspend their cynicism when they read Jackson’s reactions.

There are lions in this account, but there are no donkeys. Jackson’s view of officers was conditioned by those whom he met, and they were largely front-line soldiers like himself. His account of the death of his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel A.F. Douglas-Hamilton, who won a posthumous Victoria Cross at Loos for his brave leadership on 26 September 1915, shows his admiration for his superiors. Again and again throughout his narrative, he bears testimony, both direct and indirect, to the fellow-feeling and mutual respect that existed between officers and other ranks, and between the soldiers and their non-commissioned officers.

That was in large part the achievement of the regiment to which John Jackson belonged. In 1881 the regular infantry regiments of the British army were linked to form two-battalion regiments, with one battalion serving at home and one abroad. There was one exception to this rule, the 79th or Cameron Highlanders. This was good news for the Victorian lovers of kilts and bagpipes (and John Jackson proved to be just as much a fan as they), but it presented a major recruiting challenge as the northwest of Scotland could no longer produce sufficient men to fill so many Highland battalions. They therefore looked elsewhere in Scotland, to its industrialised central belt, poaching men that regiments from the Lowlands and borders reasonably regarded as their own. When the First World War broke out, Jackson was working in Glasgow with the Caledonia Railway. He himself hailed from Cumberland. But he joined the Camerons. His choice was determined, he tells us, by ‘the class of men joining the various units’. Before the war, military service did not attract respectable men in secure and skilled employment like Jackson. During the war such people were anxious to serve alongside those with similar backgrounds. Jackson chose wisely. Initially destined for a Territorial Battalion, the 5th, he eventually found himself in the 6th. The University of Glasgow still awards a Cameron Highlanders prize each year. It was established as a memorial by those students from the university who joined the 6th Battalion in 1914 and came back from the war in memory of those who did not. It would be easy to conclude that relations in the 6th Battalion were good and morale high because of this mix of middle-class and skilled working-class backgrounds, and that may be right. But in 1916 Jackson was transferred to the 1st Battalion – the ‘real’ 79th and a regular unit. There is no indication that fellow-feeling was any different here.

Those interested in the operations of the British Expeditionary Force and its tactical development will find many significant insights in Jackson’s experiences. His introduction to the front in 1915, at a time when the army was not under the strain it took later in the war, is striking for its good sense and its gradual nature. His criticisms of the behaviour of the men of the 21st Division at Loos, who he says were kept in the line at revolver-point by their officers, puts the fall of Sir John French, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, in a different light. French was criticised for not having straightaway released his reserve, which included the 21st Division, to the General responsible for the battle itself, Douglas Haig. The division had a trying time getting to the front, but Jackson’s narrative raises the question of whether it would have been of any use if it had got there earlier.

In 1916 Jackson was invalided back to ‘Blighty’. His account of his recuperation and re-training is illuminating. He says that veterans, as he was now deemed to be, were treated with a light hand at home. When they got back to France they went through the infamous ‘bull-ring’ at Etaples. This was where, in 1917, the British army’s only major mutiny of the war erupted. Jackson confirms that many of the non-commissioned officers ‘took a delight in making things as hard as possible’. This angered those who had been in the front line before. But Jackson’s account of the training itself leaves no doubt that it was purposeful and realistic: its toughness left its products better prepared for what awaited them.

Although Jackson took part in the advance to the Hindenburg Line (or Siegfried position as the Germans called it) in February 1917, in many ways his most interesting observations for that year concern the fighting that did not happen rather than what did. Haig’s plan for the battle of Ypres involved an amphibious landing along the Belgian coast in the rear of the German positions. Jackson trained for an operation that would have broken the trench stalemate by using British seapower to get round it. But it was forestalled by the lack of progress further south, around Ypres itself, and by the subsequent deterioration of the weather as the season advanced. The 1st Battalion, Cameron Highlanders ended its share in the battle in the mud of a front line no longer marked by trench lines but by a string of shell holes.

In early 1918, it was still in the same sector, on the receiving end of German raids, launched to disguise where the true thrust of the imminent German offensive would be directed. On 21 March the Germans attacked further south, on the old Somme battlefield, but on 9 April a second blow fell in Flanders. It hit the sector of the line held by one of two Portuguese divisions. It crumbled, and the Camerons were one of the units put in to reinforce the salient to the south in a bitter defensive battle. Jackson later went on leave to Paris, whose cultural delights enchanted him (soldiers were tourists as well as fighters), and was then gassed. But he was back for the last operations of the war, the so-called ‘hundred days’ when the British army broke the Hindenburg Line and advanced north and east.

He leaves us in no doubt of his own sense of victory. The march towards Germany brought liberation to occupied France and Belgium. On 16 December 1918, with their colours brought out from storage in Edinburgh, the Camerons entered Germany with bayonets fixed and pipes playing. When John Jackson came to record all this, in 1926, he was sure that the cause had been right and that Britain had had to fight. He was writing before the flood of war literature triggered by Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. Between 1928 and 1930 novels and memoirs bore testimony to the sense of betrayal among those who had fought. Their difficulties in re-adjusting to civilian life, to a world without war, were linked to a revulsion against the war and the reasons for it. Many of them were victims of the Slump, unemployed and purposeless. Perhaps John Jackson himself went through similar disillusionments, but if he did he did not record them – or see fit to change what he had written in his memoir. By leaving it untouched he gave us a narrative which captures another perspective, written by somebody with no obvious agenda but possessed of deep traditional loyalties – to his country, his regiment and his pals.

Hew Strachan

Chichele Professor of The History of War at theUniversity of Oxford

October 2003

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

This is a faithful reproduction of John Jackson’s original hand-written memoir. Any infelicities of spelling, grammar or language in the original manuscript have been replicated in this edition.

The Editor

Preface

In the following pages, I shall endeavour to give some description of army life during The Great War, in conjunction with some personal adventures during that period. Compiled partly from the diary I kept while on active service and partly from my own vivid recollections, I hope it may be of some little interest to all who chance to read it. The book is dedicated to the gallant 79th Regiment of Foot, ‘The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders’, in whose ranks I saw 4½ years of active service.

John Jackson MM

1st Battn Cameron Highrs

1

War!

My story begins in the memorable month of August 1914, in the city of Glasgow, where I was employed in the service of the Caledonian Railway Coy. Little need here be said of the events, which are now historical, leading up to the declaration of war against Germany, by Britain; chief of which were the Sarajevo assassination, followed later by the violation of Belgian neutrality by the hordes of the Hun, in their effort to capture the Channel ports, at a first lightning stroke. Let it ever be remembered, that but for active British intervention so early as August 4th 1914, this country of ours would not now hold her proud position as ‘Mistress of the Seas’, nor would there exist today the wonderful British Empire. Instead, German ‘Kultur’ would dominate us all, and only those who saw it in force, in the parts of France and Belgium occupied by German forces, can understand the humiliation such a situation would have entailed. The declaration of war caused tremendous excitement throughout the country, resulting in magnificent displays of patriotism on every hand. Perhaps for once in my life, I, too, was excited, as I knew it would mean a terrible fight. The spirit of adventure was always strong in me, and as news came of the departure of the British Expeditionary force, and the manner in which it met, and fought, ‘a thin line of khaki’, against the massive German columns, I knew the time had come when I could not live at peace as a civilian. A family bereavement stayed me some little time, but I was determined to go and fight, and stated my intention to enlist while on a visit home. I am proud to record there was no opposition to my wishes, though what the consequences might be, no one could foretell.

Two days later, on Sept 8th, along with a friend, Andy Johnstone, I went to the recruiting office in Cathcart Road, and there we signed on for ‘3 years or the duration’. We were sworn in and passed the doctor, and I remember the chief qualification necessary seemed to be our willingness to fight; certainly there was no real medical examination. At the recruiting office we joined company with two ticket-collectors from the Central Station, all four of us deciding to stick together as long as possible. Their names were Malcolm McLeod and Joe Symes.

2

I join the Cameron Highrs

In these early days of war, recruits had the choice of regiment they wished to join, a privilege which was denied to many thousands of men, who came under the law of compulsory service, as time went on. Had I enlisted in my own district, most likely I should have entered the Border Regt and probably this story would not have been written.

On the 10th Sept I reported, as instructed, at Maryhill Barracks, and, with my three companions discussed what regiment we should join, meanwhile taking notice of the class of men joining the various units, and finally decided on the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders – the 79th Foot, a choice of regiment which I never regretted. The barrack-square was crowded with recruits, and a very simple method was put into operation for the purpose of placing men in the battalions they wished to join. At frequent intervals, long poles bearing a crude banner, on which were inscribed the names of regiments, were hoisted in the square, and men ‘fell in’ according to their choice. Here were to be found all the signs of cheeriness that have been the ‘hall-mark’ of the British soldier during the hardest campaign ever fought. Everybody was in high spirits, for this crowd was part of ‘Kitchener’s Army’ in the raw; no need for compulsion here, and no conscientious objectors included in their ranks. The words of such a famous soldier as Lord Kitchener – ‘Your King and Country need you’ – were sufficient for the cosmopolitan crowd that we were. Workers of all grades, students, doctors, policemen, gentlemen-about-town, dukes’ sons and cooks’ sons all united under the motto, ‘For King and Country’, and all ready to see the game through to the end. Having had our papers examined, the men for the Cameron Hrs, to the number of 300, paraded at 8pm and left Maryhill by special train at 9.15pm. Our immediate destination was unknown, but we rightly judged it to be Inverness, that being the headquarters of our regiment. We created a stir at Perth, our first stop. As yet, there was no discipline amongst us, and being a lively lot, we made things hum. Apart from this the journey was uneventful, being night-time, and most of us tried to sleep. About 5am we reached Inverness, and marched to the castle over ground covered with snow. We had a miserable breakfast of bread and cheese and some half-cold tea. There was no sitting down to tables or being waited on. It was simply a wild scramble, such as respectable people could not imagine, and a very rough introduction to army life. It was no use waiting till the scramble had subsided. That only meant we should get nothing, so, like hundreds of others had to do, I scrambled for food. During the day we paraded, and each received a regimental number the figures 12768 being tacked on to my name. Afterwards, I had a walk through the town. Inverness is quiet, and clean.

From the castle, which stands out prominently on high ground, magnificent views of the in-lying country and the shores of the Moray Firth can be obtained. The barracks themselves are fine stone buildings, with spacious courtyard or square, for parade purposes. During the afternoon volunteers were called for to join the 5th (Lochiel’s) Camerons, then lying at Aldershot, and as this seemed to us to be a step in the direction of France and the fighting line, we four gave in our names, and received orders to be ready to leave by the 4.20pm train, so that we were less than 12 hours at our depot. The volunteer party consisted of 100 men, and headed by the depot band, we marched down from the Castle to the station. Like many thousands of others, we had a rousing send-off from the people of Inverness, who showed the greatest enthusiasm, while the liveliness of our party was undoubted.

On a fine, September, evening, then, we set off on our journey south, and in the light of a summer sun we viewed the magnificent scenery, as the train ran through the Highlands. Towering mountains of rugged grandeur, their tops glistening with snow, peaceful glens and valleys, swift rushing streams that leapt and foamed among the rocks, and calm lochs in their moorland settings, left a picture in the memory which nothing could surpass. With a speed that made us hold on to the seats we swept through the Trossachs, and the famous pass of Killiecrankie, and as the twilight faded into darkness we arrived at Perth. During a stay of 20 minutes, we were lavishly supplied with hot tea, scones and cakes by ladies of the British Women’s Temperance Association. For this kindness we were all very grateful to the ladies concerned, and gave them a rousing good cheer as our train steamed away from the platform on its way south. Reaching Carlisle in the early morning, we halted just long enough to change engines before continuing our journey via the L.N.W. railway to London. Here, after a cup of tea, which was all we had in the way of breakfast, we passed by way of the ‘Tube’ to Waterloo Station, and having some time to wait for our connection, many of us had our first walk on the streets of London. Soon we had entered on the last stage, and in due course reached the great military centre of Aldershot, after a journey occupying 21hours. On arrival at the barracks, all the men belonging to the Western Highlands were asked to step forward. I believe there were two, and these were the only men out of the party sent specially to join the 5th Battalion who actually entered its ranks. The remainder were marched off to the gymnasium in Maida Barracks, which was to be our temporary residence. This was the beginning of the roughest period of my experience as a soldier at home. We were each given a boiled potato (skin included) and a piece of meat for our dinner. We did not have plates, knives, or forks, nor yet tables to sit at. No, our tables were the floor-boards. Perhaps allowances should be made at this time, for the unpreparedness of the authorities, with regard to the abnormal numbers of recruits, but with all things considered it was sickening to men, who had previously known decent home-life. We became more like animals than humans, and only by scrambling and fighting like dogs were we able to get food to eat. Some may read this and imagine that I exaggerate, but men who went to Aldershot in 1914 know I speak the truth. Our bedding was a solitary blanket, and our bed the block-paved floor of the gymnasium, so our training to withstand hardships began on arrival. Fatigued, as we were with our long journey from the north, we slept soundly, though perhaps many of us dreamt, that first night, of the good soft beds we had left at home.

3

Forming the 6th Battalion

At the time of my arrival at Maida Barracks, there were some 500 men, who did not belong to any particular battalion at all, and as the 5th Camerons had completed their strength, sanction was given to raise another battalion which came to be known as the 6th Camerons. A skeleton formation was made the day following our arrival, and we four friends, still determined to stick together, were placed in the third or ‘C’ company. When all the arrangements were completed, we were dismissed for the day, it being Sunday. It must not be forgotten that we were all wearing civilian clothes, many indeed wore their best, so we did not look much like soldiers of H.M. Army. In the evening we were given a kit-bag, and some minor articles of kit. For some time very few of us had such a thing as a towel; we learned to make a handkerchief do. We found Aldershot to be a hive of soldiers in different stages of training. In addition to the various regular barracks, camps had been formed wherever space could be found. As a training centre it is splendidly situated, and fashioned on modern ideas and requirements. Each barracks is complete in itself, from its officers’ and ‘married’ quarters, to a well appointed cook-house and general offices.

Recreation grounds, then used for encampments were everywhere, also comfortable recreation rooms and reading rooms. A well known building in Aldershot was the ‘Smith-Dorrien’ Soldiers’ Home, which contained a billiard-room, reading and writing rooms and a good library. In it were also a post-office, private baths, and a buffet, where light refreshments could be purchased. The ‘Home’ was always crowded when men were off duty, and many thousands of men will have pleasant recollections of happy evenings at the Smith Dorrien Home. The different barracks were separated by splendidly kept drives, which were bordered by gardens and shrubberies. At Farnborough, just outside the camp, airships and aeroplanes could be seen manoeuvring and flying about like huge birds. To us, from the north, all this was new and extremely interesting. The surrounding district, bordering on the ‘Downs’, was very much different from what we had been accustomed to, while the weather was fine and sunny. Immediately following the formation of the 6th Camerons, we commenced the drill, so necessary to make us efficient soldiers. We found it very hard, fatiguing work at the beginning, as we learned to march, form fours, about turn, and all the mystifying movements of that bane of recruits life, ‘Squad Drill’. Our instructors were chiefly old reserve soldiers; indeed we were very fortunate in having so many who had served in the senior battalions of our own regiment. One of these instructors I remember especially well as he became my company Sgt Major at a later date. This N.C.O. appeared before us one morning, and it was very evident, despite the fact that he wore a nice grey suit, what his business was. He was very smart and very strict, but knew his work thoroughly and turned out some very smart squads. A few days later we were introduced to yet another ex-regular, dressed in blue serge, and carrying a silver mounted cane. This was John Macdonald late Regimental-Sergeant-Major of the 1st Battalion, a terror to recruits, and all under him on parade, but a gentleman off it. He became known to us as ‘Jake’, and when after a months stay, he left us, he was promoted to commissioned rank as Qr Master of the newly formed 8th Battn. As most days for some time were identical, a description of one will give a fair idea of the work we did at this period. Reveille went at 5.30am, and after a cup of coffee we turned out at 6.30 for what we called running parade. This consisted of a steady trot, or ‘double’, and short walk alternately, finishing up with a few minutes physical drill. We breakfasted at 8, and turned out again at 9.30 for squad drill till 12.15pm. Then dinner and parade at 2pm for more drill till 4.15pm. This ended our days work unless we were unlucky and got detailed for some ‘fatigue’ or work party. ‘Last Post’ sounded at 9.30 and ‘Lights out’ half an hour later, so we learned to keep respectable hours. Under our open-air life we became very bronzed and hardened. A great trouble, to many fellows, was sore feet, and the gravelled parade grounds of Aldershot were ideal places for raising blisters and making the feet uncomfortable. I was very lucky in having sound feet, and suffered little in this respect during all the campaign.

4

Rushmoor Camp

Having, through the addition of various drafts, become a larger body of men than the gymnasium was capable of accommodating, we left Maida Barracks on the 23rd of September for a camp at Rushmoor, on the outskirts of Aldershot. Life in tents under good conditions is fine, but it is not very nice when 14 or 15 men occupy one tent in hot weather, and it was hot at this time. What was much worse, we found the whole camp in a verminous condition, and we became very much infested with ‘small mites of the crawling and biting variety’. We had no beds to sleep on; two blankets constituted our total in bedclothes, and our boots served the purpose of pillows. Near us were camped the 9th & 10th Gordons, the 11th Argyll and Sutherlands and the 13th Royal Scots. Soon after our arrival at Rushmoor, the rumour went round that the King was to pay us a visit, and we began practising formations for his inspection. We had our ‘Royal Review’ on Sept 26th on the ‘Queen’s Parade’ Aldershot. 120,000 men were present, many of whom, like ourselves, wore civilian clothes. I remember that I wore the linen collar I had on when I joined up, but for this occasion I turned it wrong side out to appear as respectable as possible.

The day was very hot when the Royal visitors arrived. The Camerons had position on the left flank, and I was lucky enough to be in the front rank. First of all came the King attended by Lord Kitchener, easily recognised by his immense size. Following these came the Queen and Princess Mary with two Court Ladies in attendance. In rear of the Royalty were Sir A. Hunter, Chief of the Aldershot Command, and his Staff. The Royal party I had seen before, but I was very pleased to have the opportunity of seeing the great soldier, Lord Kitchener. Very stern and commanding he looked as he passed along the ranks, a centre of interest to the thousands standing to attention on parade. At the conclusion of the review, three mighty cheers were given for their Majesties, after which we marched back to the camp, the rest of the day being spent as a holiday. Shortly after this, we experienced a very welcome change in our drills. From the monotony of ‘squad drill’ we passed on to ‘extended’ or ‘skirmishing order’, as it was more popularly called, which allowed us much more freedom of movement. We learned to work to signals instead of commands, and began to get more interested in soldiering. Night operations were also introduced, while once or twice a week we went route-marching. This latter was perhaps the only parade one could say we really enjoyed, as it gave us opportunities of seeing round the surrounding district. We were encouraged in the practice of singing on the march officers and men joining in together. A great favourite was ‘Auld Reekie’, the only verse of which ran as follows:

Oh! I can’t forget ‘Auld Reekie’

Dear old Edinburgh ‘Toon’

For I left my heart behind me

Wi’ bonnie Jessie Broon

But I’ll wear a sprig o’ heather

When I’m on a foreign shore

To remind me of ‘Auld Reekie’

And the lassie I adore.

To this and many other songs we marched many a mile along country roads of sunny Surrey, and Hampshire. As time went on the battalion. became possessed of a pipe band which evoked rounds of applause as it played through the villages.

Autumn was now advancing, with its shortening days and dark evenings, and the want of means of recreation was very much felt in the camp. During the last few weeks of our stay at Rushmoor, concerts were organised, by some of the junior officers, and these were held once a week. The number of voluntary artists who came forward, and contributed to these entertainments was surprising, and included singers, pianists, violinists, comedians and dancers. Many a pleasant evening was spent in a large marquee, which served as a ‘Hall’ for our concerts. About this time we were issued with our first uniforms and a funny looking lot we were when dressed up. I got hold of a regimental tunic of scarlet, complete with blue cuffs and white facings, together with blue trousers sporting a red stripe. Camp life soon spoiled their appearance, but they were all we had for a long time. We were supplied also with rifles, and began to look like real soldiers. We had much useful instruction given us on the care and handling of our weapons and found ourselves having extra work keeping them clean. There was now a general break-down in the weather, and we found camp life anything but sweet, amongst rain and mud. Generally when it was wet we had lectures in marquees on the methods of fighting at the front, also on trenches and various other interesting items. Sometimes, however, we were caught out in the rain; I particularly remember doing a route march one day, 11 miles out and 11 miles back to camp, while it poured down. We had no overcoats, and nothing to change into on our arrival home, so we just had to grin and bear it. I suppose this should be termed the ‘hardening process’. Dodging rain drops which came through the tents, was a favourite pastime in bed on a wet night, while it was a common occurrence to find water in our boots in the morning. The camp got into a terrible mess, and so did we as we floundered about amongst the mud. With the weather conditions so bad, we were daily expecting to be moved to better quarters but it was not till 16th November that we packed up at Rushmoor Camp. We learned we were going to one of the many hutment camps, which at this time were being built for the accommodation of troops in many parts of the southern counties. From Aldershot, we proceeded via the London and South Western Railway to a little station named Liphook. Detraining here, we marched to Bramshott Camp, situated on the London–Portsmouth road, now so well known as the training camp of thousands of Canadian soldiers. The 45th (our) brigade, with the 46th, were the first occupants of this famous camp, and we found it in a semi-finished condition on our arrival. A small army of men was busy erecting huts, while a continuous stream of motor wagons passed to and fro, carrying building materials, both for huts and roadways.

5

Life at Bramshott

I cannot admit, either from first impressions, or from our experience of it, that we ever cared for Bramshott Camp. The huts and their environs were nothing less than a quagmire, so much so that at times it was impossible to ‘form up’ on the parade ground and we had to make use of the main road, very often, for this purpose. We did a great deal towards making roads and pathways through the camp, work that we did not relish very much I must say, as the weather was generally very cold and wet. For our training ground we were allowed the use of the Wolmer Park estate, parts of which were eminently suitable for open-warfare training as it contained large tracts of scrub and moorland. We continued to progress in our musketry, and began to practise in shooting, commencing on the minature ranges. Great attention was still paid to our marching. We had now regular route-marches, and began to be well acquainted with the district. The roads were splendid to walk on, and we discovered many beautiful woods and interesting villages. A prominent feature of the district is the large number of road-side hotels, suggesting that the beautiful scenery succeeds in attracting many visitors during the holiday season. Not many miles from the camp, and along the Portsmouth road, is a very wonderful natural depression of the ground, having the curious name of ‘The Devil’s Punch Bowl’. It is like a huge cup with very steep sides and a circumference of about two miles. Many a fine imitation battle have we fought through the Punch Bowl, with its dense undergrowth, its fine trees, its whins and thorns that made you move on whether you wished to or not. Our night manoeuvres must have often alarmed the people of the peaceful south-country villages; to be wakened in the middle of the night by a wild rush of feet along the village street, accompanied by ‘wild Hie’lan’ yells’ could not be conducive to calm sleep and pleasant dreams. Generally speaking, however, the inhabitants took everything in good part, and the majority thought a lot of the ‘Jocks’, which the exigencies of the war had brought among them. To help pass away the long winter evenings, a large marquee had been erected near the camp, and this we used as a reading and writing room. There was also one in which cinema shows were frequently given. Concerts too were organised, at which many local ladies were voluntary artists It was not uncommon, either, for a large party of men to be invited to a supper and social evening, by ladies of the outlying villages, such was the good feeling existing between the people and ourselves.

Christmas was now drawing near, and we began to think of ‘leave’, and a few days at home. In due course we went on furlough, and I well remember how we paraded in the early hours of a wintry morning, and marched down to Liphook Station, en route for London and thence home. For my part I was glad of the few days, which I spent among friends at home, though the time passed all too soon. Going on leave is very nice but the return to camp in this instance was a ‘knock-out’. After a miserable journey back to Bramshott, via London, on arrival we found that the windows of our huts had been opened during our absence and our blankets were soaking with the rain which had driven in. Tired, and weary as we were, after our long journey, we could only pass the remainder of the night trying to keep warm by walking about the hut. Soon after this there arrived, in a draft from Invergordon, a young fellow who belonged to Kendal, by name of Charlie Hutchinson, and between us there sprang up a lasting friendship. He was allotted to my section and took the place in my immediate circle of friends, of Joe Symes, who for some trivial fault had been transferred to the Royal Scots Fusiliers some time before.

We began the year 1915 by having a holiday on New Year’s Day, and enjoying a grand dinner given to ‘C’ company, by our popular company commander Captain Crichton. Needless to say we did full justice to the good feast provided. We were now busily engaged in our musketry training and for the purpose of firing our courses, had to tramp to Longmoor Range every day. I think we all liked range-firing, and competition was keen amongst us as to who could make the highest score. On January 22nd the whole of the 15th Division comprising (in infantry):

44th Bde:

7th Camerons, 8th and 9th Gordons & 9th Watch

45th Bde:

6th Camerons, 11th Argylls, 7th R.S. Fusiliers, 12th H.L.I.

46th Bde:

7th & 8th Seaforths, 7th & 8th K.O.S.B. and 13th Royal Scots

were reviewed on Frensham Common by Lord Kitchener and M. Millerand, the French Minister for War. From our camp to Frensham was a distance of 9 miles, and this we marched in the fiercest of winter weather. We carried no great-coats, although snow fell all day, and for 3 hours we stood waiting, numb and cold, for our visitors. Many a poor beggar fainted under the trying ordeal, and was carried off on a stretcher. Through the stampeding of an officer’s charger, we were treated to a fine exhibition of horsemanship on the part of our transport officer, an ex-Canadian rancher, who succeeded in rounding up the runaway in true cowboy fashion, after an exciting chase on the common, to the cheers of 20,000 onlookers. Our struggle back to Bramshott through a foot of snow comes back to my memory, as clearly as if it happened yesterday, with the brutal voice of our second-in-command, the Earl of Seafield, forever ordering us to ‘keep to the left’, on a road which was little removed from a cart-track. The 1st of February brought to an end our range-firing, and thereafter we returned to our drills, our route-marches and fatigues. We had also had a large amount of trench digging, and this to many fellows unused to handle a spade, was a heart-breaking job. Always, however, we had our fun as we worked and the startled exclamation of a man engaged in trench work by night, as he found a pick sent neatly through the seat of his trousers, taught one to be careful as to who was working behind him. I’m sure officers must have been forced to smile at what they heard sometimes under cover of the darkness of night. We were now so well advanced in our training, that a half holiday was allowed us on Saturdays, and numbers of men made use of the weekends to visit London or Portsmouth. Sunday mornings found every available man on Church Parade. The majority, belonging to the Presbyterian Church, attended a massed brigade service, generally held in the open air. A small number belonged to the Church of England, myself being one of these few, and we were allowed to attend service at the parish church at Bramshott, where we were always welcomed, and treated with every courtesy. We had now reached the middle of February, and rumours were current that we would soon be moved again. On the 18th an advance party of Black Watch and Gordons of the 44th Brigade arrived in Bramshott to take over our billets, while a party of our own men left for Basingstoke. Certain now that we were leaving Bramshott, our hearts grew light, and we did not mind the numerous hard fatigues such a movement of troops entails. It was whispered we were going into ‘private billets’ which meant a sort of heaven to us, after our rough experiences at Rushmoor and Bramshott. We cleaned and scrubbed our huts and bed-boards; in fact everything that would scrub, got its share. We paid final visits to the surrounding villages wondering perhaps if we should ever meet such good friends again. To the villagers it was to be a sore parting, their ‘Jocks’ were leaving them at last. We were the recipients of sincere good wishes on every hand, but while regretting the loss of such warm-hearted friends, I think none of us were sorry to say farewell to the muddy precincts of Bramshott Camp.

6

Billeted in Basingstoke

At mid-day on the 20th of February we marched out of Bramshott Camp to the strains of ‘The 79th’s Farewell’ played by the pipers, and entrained at Liphook travelling from there, via Petersfield, Redhampton, Porchester and Winchester to Basingstoke. On our arrival, it was found there was insufficient accommodation in the town for the whole regiment, and accordingly my company were billeted protem in the small village of Worting situated about 2 miles north of Basinstoke. I considered myself very fortunate in being allotted to the house of a signalman named Bradbeer, whose wife, a Devonshire woman, showed me the greatest kindness and I shall ever have pleasant memories of my stay with these people. It was of course a decided change for us to have a good house to stay in, and real, comfortable, beds to sleep in, accustomed as we had been for some months to roughing it in camp. As at Bramshott the people round about were all good to us, and spared no effort to make us feel at home amongst them. Concerts, whist parties etc, were arranged for our pleasure, thus showing the generous hospitality of these friendly south country people. About the end of the month the battalion was issued with its proper uniform of kilts and khaki tunics, and so at last we were able to dress as befitted a proud Highland regiment. I well remember our first parade in kilts; how smart we all appeared, and how the C.O. Col Douglas-Hamilton surveyed with evident pleasure, the ranks of his men as he passed up and down on horseback.

Accommodation having now been found in Basingstoke, my company was transferred to their new billets in town on March 12th. Again I had a splendid billet with a Mr Purdue in George Street, and had for a room-mate my good friend Charlie Hutchinson. Here again, our landlady was very kind, and everything was made very pleasant for us. Charlie and I often went to church services with Mr Purdue, a jolly good fellow, who did all in his power to show us all there was to be seen and known in the district. As often as possible we visited our good friends in Worting, where we were always made welcome.

Our military training was now reaching advanced stages. Route marching, always the most enjoyable of parades made us familiar with a large part of Hampshire, the length of marches being gradually extended till we were hardened to perfection, and it would have been a remarkable regiment that could have endured the pace and fatigue alongside of us on the march. ‘A Cameron never can yield’ was an appropriate motto for us, there was no ‘give in’ attached to the 6th Camerons. Night operations, too, became much in vogue, including trench digging, sham fights and forced marches, and from these hard nights we used to return to our billets at all hours, and Charlie and I were always ready for the hot cocoa, left ready for us by our landlady, before tumbling into bed. Our training, if hard, was very interesting, and allowed us much freedom of movement; moreover it kept us very healthy, and from the open-air life we were in a hard and splendid condition. We were fast becoming finished soldiers, and knew our time in this country would be short, but everyone was anxious to be out among the real fighting. Perhaps we did not fully understand what it meant, but we were full of enthusiasm and confidence in our ability as a regiment to make a good name once we had the chance. We had a brigade inspection on Basingstoke Common on March 18th, by Gen. Pitcairn Campbell, O.C. Southern Command, which passed off very well.

The scene of much of our training was the beautiful surroundings of Hackwood Park, the home of Lord Curzon, and it was here that the Queen of Belgium and her children were then staying as ‘refugees’ from the war. Field games were very much indulged in at this time, football being the chief attraction. We had quite a good regimental team, and many were the friendly tussles we had with the rest of our brigade, and also the local teams of the town. There was great rivalry between the Cameron team and that of the Argylls, the merits and performances of the two teams being about equal, and there was sure to be a battle royal when they met in games.

On April 3rd we were issued with new leather equipment which puzzled us for some time, before we got it correctly put together. This was something more for us to keep clean, and, of course was responsible for not a little ‘grousing’.

Bayonet fighting now became very much in evidence, during this period in our training, as did also trench digging by night. Skirmishing and sham battles we always enjoyed whether by day or night, and we tramped many miles during these operations. I remember one day having a mimic battle at Winklebury, said to be the scene of a battle in old English history. Our objective this day was Winklebury Hill held by the Argyll and Sutherland Highrs, and after various manoeuvres, extending over some hours, we were adjudged to have been successful in our attack, and to have captured the position held by our rivals.

Our pleasant stay at Basingstoke could not last for ever, and after about six weeks we began to make preparations for yet another move. The trenches were all filled in at Hackwood Park and this took a good deal of work, though not nearly so much as it took to dig them. Once more we had to say ‘Goodbye’ to good friends, whose kindness will always remain a pleasant memory. We handed in our extra kit and blankets on Sunday April 25th, and made ready for moving next morning; the beginning of a march I’ll never forget.