1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Librorium Editions

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This exposé, based on facts which have come to my knowledge, though probably far from being complete, aims at depicting the recent state of things in Russia, and thus to explain how the great changes which have taken place in my country have been rendered possible. A lot of exaggerated tales have been put into circulation concerning the Empress Alexandra, the part she has played in the perturbations that have shaken Russia from one end to another and the extraordinary influence which, thanks to her and to her efforts in his behalf, the sinister personage called Rasputin came to acquire over public affairs in the vast empire reigned over by Nicholas II. for twenty-two years. A good many of these tales repose on nothing but imagination, but nevertheless it is unfortunately too true that it is to the conduct of the Empress, and to the part she attempted to play in the politics of the world, that the Romanoffs owe the loss of their throne.

Alexandra Feodorovna has been the evil genius of the dynasty whose head she married. Without her it is probable that most of the disasters that have overtaken the Russian armies would not have happened, and it is certain that the crown which had been worn by Peter the Great and by Catherine II. would not have been disgraced. She was totally unfit for the position to which chance had raised her, and she never was able to understand the character or the needs of the people over which she ruled.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

RASPUTIN AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

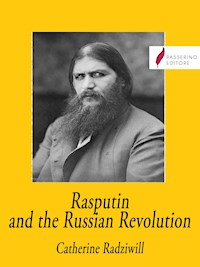

Photo by Paul Thompson

Gregory Rasputin “The Black Monk of Russia”

RASPUTINAND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

BY

PRINCESS CATHERINE RADZIWILL(COUNT PAUL VASSILI)

AUTHOR OF “BEHIND THE VEIL AT THE RUSSIAN COURT,” “GERMANY UNDER THREE EMPERORS,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

1917

© 2022 Librorium Editions

ISBN : 9782383833864

TOMONSIEUR JEAN FINOTEditor of the “Revue”

My dear Mr. Finot:—

Allow me to offer you this little book, which may remind you of the many conversations we have had together, and of the many letters which we have exchanged. In doing so, I am fulfilling one of the pleasantest of duties and trying to express to you all the gratitude which I feel towards you. Without your kind help, and without your advice, I would never have had the courage to take a pen in my hand, and all the small success I may have had in my literary career is entirely due to you, and to the constant encouragement which you have always given to me, and which I shall never forget, just as I shall always remember that it was in the “Revue” that the first article I ever published appeared. Permit me to-day to thank you from the bottom of my heart, and believe me to be,

Always yours most affectionately,Catherine Radziwill(Catherine Kolb-Danvin)

PUBLISHERS FOREWORD

When the book called “Behind the Veil at the Russian Court” was published the Romanoff’s were reigning and, considering the fact that she was living in Russia at the time, the author of it, had her identity become known, would have risked being subjected to grave annoyances, and even being sent to that distant Siberia where Nicholas II is at present exiled. It was therefore deemed advisable to produce that work as a posthumous one, and “Count Paul Vassili” was represented as having died before the publication of “his” Memoirs. This however was not the case, because on the contrary “he” went on collecting information as to all that was taking place at the Russian Court as well as in the whole of Russia, and, consigning this information to a diary, “he” went on writing. If one remembers, “Count Vassili” distinctly foresaw and prophesied in “his” book most of the things that have occurred since it was published. This fact will perhaps give added interest to the present account of the Russian Revolution which now sees the light of day for the first time. Though devoid of everything sensational or scandalous it will prove interesting to those who have cared for the other books of “Count Vassili,” for it contains nothing but the truth, and has been compiled chiefly out of the narrations of the principal personages connected in some way or other with the Russian Revolution. The facts concerning Rasputin, and the details of this man’s extraordinary career, are, we believe, given out now for the first time to the American public, which, up to the present moment, has been fed on more or less untrue and improbable stories or, rather, “fairy tales,” in regard to this famous adventurer. The truth is far simpler, but far more human, though humanity does not shine in the best colours in its description.

PART I

RASPUTIN

INTRODUCTION

This exposé, based on facts which have come to my knowledge, though probably far from being complete, aims at depicting the recent state of things in Russia, and thus to explain how the great changes which have taken place in my country have been rendered possible. A lot of exaggerated tales have been put into circulation concerning the Empress Alexandra, the part she has played in the perturbations that have shaken Russia from one end to another and the extraordinary influence which, thanks to her and to her efforts in his behalf, the sinister personage called Rasputin came to acquire over public affairs in the vast empire reigned over by Nicholas II. for twenty-two years. A good many of these tales repose on nothing but imagination, but nevertheless it is unfortunately too true that it is to the conduct of the Empress, and to the part she attempted to play in the politics of the world, that the Romanoffs owe the loss of their throne.

Alexandra Feodorovna has been the evil genius of the dynasty whose head she married. Without her it is probable that most of the disasters that have overtaken the Russian armies would not have happened, and it is certain that the crown which had been worn by Peter the Great and by Catherine II. would not have been disgraced. She was totally unfit for the position to which chance had raised her, and she never was able to understand the character or the needs of the people over which she ruled.

Monstrously selfish, she never looked beyond matters purely personal to her or to her son, whom she idolized in an absurd manner. She, who had been reared in principles of true liberalism, who had had in her grandmother, the late Queen Victoria, a perfect example of a constitutional sovereign, became from the very first day of her arrival in Russia the enemy of every progress, of every attempt to civilise the nation which owned her for its Empress. She gave her confidence to the most ferocious reactionaries the country possessed. She tried, and in a certain degree succeeded, in inspiring in her husband the disdain of his people and the determination to uphold an autocratic system of government that ought to have been overturned and replaced by an enlightened one. Haughty by nature and by temperament, she had an unlimited confidence in her own abilities, and especially after she had become the mother of the son she had longed for during so many years, she came to believe that everything she wished or wanted to do had to be done and that her subjects were but her slaves. She had a strong will and much imperiousness in her character, and understood admirably the weak points in her husband, who became but a puppet in her hands.

* * * * *

She herself was but a plaything in the game of a few unscrupulous adventurers who used her for the furtherance of their own ambitious, money-grubbing schemes, and who, but for the unexpected events that led to the overthrow of the house of Romanoff, would in time have betrayed Russia into sullying her fair fame as well as her reputation in history.

* * * * *

Rasputin, about whom so much has been said, was but an incident in the course of a whole series of facts, all of them more or less disgraceful, and none of which had a single extenuating circumstance to put forward as an excuse for their perpetration.

* * * * *

He himself was far from being the remarkable individual he has been represented by some people, and had he been left alone it is likely that even if one had heard about him it would not have been for any length of time.

* * * * *

Those who hated him did so chiefly because they had not been able to obtain from him what they had wanted, and they applied themselves to paint him as much more dangerous than he really was. They did not know that he was but the mouthpiece of other people far cleverer and far more unscrupulous even than himself, who hid themselves behind him and who moved him as they would have done pawns in a game of chess according to their personal aims and wants. These people it was who nearly brought Russia to the verge of absolute ruin, and they would never have been able to rise to the power which they wielded had not the Empress lent herself to their schemes. Her absolute belief in the merits of the wandering preacher, thanks to his undoubted magnetic influence, contrived to get hold of her mind and to persuade her that so long as he was at her side nothing evil could befall her or her family.

It is not generally known outside of Russia that Alexandra Feodorovna despised her husband, and that she made no secret of the fact. She considered him as a weak individual, unable to give himself an account of what was going on around him, who had to be guided and never left to himself. Her flatterers, of whom she had many at a time, had persuaded her that she possessed all the genius and most of the qualities of Catherine II., and that she ought to follow the example of the latter by rallying around her a sufficient number of friends to effect a palace revolution which would transform her into the reigning sovereign of that Russia which she did not know and whose character she was unable to understand. Love for Nicholas II. she had never had, nor esteem for him, and from the very first moment of her marriage she had affected to treat him as a negligible quantity. But influence over him she had taken good care to acquire. She had jealously kept away from him all the people from whom he could have heard the truth or who could have signalled to him the dangers which his dynasty was running by the furtherance of a policy which had become loathsome to the country and on account of which the war with Germany had taken such an unexpected and dangerous course.

The Empress, like all stupid people, and her stupidity has not been denied, even by her best friends, believed that one could rule a nation by terror. She, therefore, always interposed herself whenever Nicholas II. was induced to adopt a more liberal system of government and urged him to subdue by force aspirations it would have been far better for him to have encouraged. She had listened to all the representatives of that detestable old bureaucratic system which gave to the police the sole right to dispose of people’s lives and which relied on Siberia and the knout to keep in order an aggrieved country eager to be admitted to the circle of civilised European nations.

Without her and without her absurd fears, it is likely that the first Duma would not have been dissolved. Without her entreaties, it is probable that the troops composing the garrison at St. Petersburg would not have been commanded to fire at the peaceful population of the capital on that January day when, headed by the priest Gapone, it had repaired to the Winter Palace to lay its wrongs before the Czar, whom it still worshipped at that time. She was at the bottom of every tyrannical action which took place during the reign of Nicholas II. And lately she was the moving spirit in the campaign, engineered by the friends of Rasputin, to conclude a separate peace with Germany.

In the long intrigue which came to an end by the publication of the Manifesto of Pskov, Rasputin undoubtedly played a considerable part, but all unconsciously. Those who used him, together with his influence, were very careful not to initiate him into their different schemes. But they paid him, they fed him, they gave him champagne to drink and pretty women to make love to in order to induce him to represent them to the Empress as being the only men capable of saving Russia, about which she did not care, and her crown, to which she was so attached. With Rasputin she never discussed politics, nor did the Emperor. But with his friends she talked over every political subject of importance to the welfare of the nation, and being convinced that they were the men best capable of upholding her interests, she forced them upon her husband and compelled him to follow the advice which they gave. She could not bear contradiction, and she loved flattery. She was convinced that no one was more clever than herself, and she wished to impose her views everywhere and upon every occasion.

Few sovereigns have been hated as she has been. In every class of society her name was mentioned with execration, and following the introduction of Rasputin into her household this aversion which she inspired grew to a phenomenal extent. She was openly accused of degrading the position which she held and the crown which she wore. In every town and village of the empire her conduct came to be discussed and her person to be cursed. She was held responsible for all the mistakes that were made, for all the blunders which were committed, for all the omissions which had been deplored. And when the plot against Rasputin came to be engineered it was as much directed against the person of Alexandra Feodorovna as against that of her favourite, and it was she whom the people aimed to strike through him.

Had she shown some common sense after the murder of a man whom she well knew was considered the most dangerous enemy of the Romanoff dynasty things might have taken a different course. Though every one was agreed as to the necessity of a change in the system of government of Russia, though a revolution was considered inevitable, yet no one wished it to happen at the moment when it did, and all political parties were agreed as to the necessity of postponing it until after the war. But the exasperation of the Empress against those who had removed her favourite led her to trust even more in those whom he had introduced and recommended to her attention. She threw herself with a renewed vigour into their schemes, urging her husband to dishonour himself, together with his signature, by turning traitor to his allies and to his promises. She wanted him to conclude a peace with Germany that would have allowed her a free hand in her desires to punish all the people who had conspired against her and against the man upon whom she had looked as a saviour and a saint. Once this fact was recognised the revolution became inevitable. It is to the credit of Russia that it took place with the dignity that has marked its development and success.

This, in broad lines, is the summary of the causes that have brought about the fall of the Romanoff dynasty, and they must never be lost sight of when one is trying to describe it. It is, however, far too early to judge the Russian revolution in its effects because, for one thing, it is far from being at an end, and may yet take quite an unexpected turn. For another, the events connected with it are still too fresh to be considered from an objective point of view. I have, therefore, refrained from expressing an opinion in this narrative. My aim has been to present to my readers a description of the personality of Rasputin, together with the part, such as I know it, that he has played in the development of Russian history during the last five years or so, and afterward to describe the course of the revolution and the reasons that have led to its explosion in such an unexpected manner.

CHAPTER I

We live in strange times, when strange things happen which at first sight seem unintelligible and the reason for which we fail to grasp. Even in Russia, where Rasputin had become the most talked-of person in the whole empire, few people fully realised what he was and what had been the part which he had played in Russia’s modern history. Yet during the last ten years his name had become a familiar one in the palaces of the great nobles whose names were written down in the Golden Book of the aristocracy of the country, as well as in the huts of the poorest peasants in the land. At a time when incredulity was attacking the heart and the intelligence of the Russian nation the appearance of this vagrant preacher and adept of one of the most persecuted sects in the empire was almost as great an event as was that of Cagliostro during the years which preceded the fall of the old French monarchy.

There was, however, a great difference between the two personages. One was a courtier and a refined man of the world, while the other was only an uncouth peasant, with a crude cunning which made him discover soon in what direction his bread could be buttered and what advantages he might reap out of the extraordinary positions to which events, together with the ambitions of a few, had carried him. He was a perfect impersonation of the kind of individual known in the annals of Russian history as “Wremienschtchik,” literally “the Man of the Day,” an appellation which since the times of Peter the Great had clung to all the different favourites of Russian sovereigns. There was one difference, however, and this a most essential one. He had never been the favourite of the present Czar, who perhaps did not feel as sorry as might have been expected by his sudden disappearance from the scene of the world.

I shall say a thing which perhaps will surprise my readers. Personally, Rasputin was never the omnipotent man he was believed to be, and more than once most of the things which were attributed to him were not at all his own work. But he liked the public to think that he had a finger in every pie that was being baked. And he contrived to imbue Russian society at large with such a profound conviction that he could do absolutely everything he chose in regard to the placing or displacing of people in high places, obtaining money grants and government contracts for his various “protégés,” that very often the persons upon whom certain things depended hastened to grant them to those who asked in the name of Rasputin, out of sheer fright of finding this terrible being in their way. They feared to refuse compliance with any request preferred to them either by himself or by one who could recommend himself on the strength of his good offices on their behalf. But Rasputin was the tool of a man far more clever than himself, Count Witte. It was partly due to the latter’s influence and directions that he tried to mix himself up in affairs of state and to give advice to people whom he thought to be in need of it. He was an illiterate brute, but he had all the instincts of a domineering mind which circumstances and the station of life in which he had been born had prevented from developing. He had also something else—an undoubted magnetic force, which allowed him to add auto-suggestion to all his words and which made even unbelieving people succumb sometimes to the hypnotic practices which he most undoubtedly exercised to a considerable extent during the last years of his adventurous existence.

Amidst the discontent which, it would be idle to deny, had existed in the Russian empire during the period which immediately preceded the great war the personality of Rasputin had played a great part in giving to certain people the opportunity to exploit his almost constant presence at the side of the sovereign as a means to foment public opinion against the Emperor and to throw discredit upon him by representing him as being entirely under the influence of the cunning peasant who, by a strange freak of destiny, had suddenly become far more powerful than the strongest ministers themselves. The press belonging to the opposition parties had got into the habit of attacking him and calling his attendance on the imperial court an open scandal, which ought in the interest of the dynasty to be put an end to by every means available.

In the Duma his name had been mentioned more than once, and always with contempt. Every kind of reproach had been hurled at him, and others had not been spared. He had become at last a fantastic kind of creature, more exploited than exploiting, more destroyable than destructive, one whose real “rôle” will never be known to its full extent, who might in other countries than Russia and at another time have become the founder of some religious order or secret association. His actions when examined in detail do not differ very much from those of the fanatics which in Paris under the reign of Louis XV. were called the “Convulsionnaires,” and who gave way to all kind of excesses under the pretext that these were acceptable to God by reason of the personality of the people who inspired them. In civilised, intelligent, well-educated Europe such an apparition would have been impossible, but in Russia, that land of mysteries and of deep faiths, where there still exist religious sects given to all kinds of excesses and to attacks of pious madness (for it can hardly be called by any other name), he acquired within a relatively short time the affections of a whole lot of people. They were inclined to see in him a prophet whose prayers were capable of winning for them the Divine Paradise for which their hungry souls were longing. There was nothing at all phenomenal about it. It was even in a certain sense quite a natural manifestation of this large Russian nature, which is capable of so many good or bad excesses and which has deeply incrusted at the bottom of its heart a tendency to seek the supernatural in default of the religious convictions which, thanks to circumstances, it has come to lose.

The American public is perhaps not generally aware of the character of certain religious sects in Russia, which is considered to be a country of orthodoxy, with the Czar at its head, and where people think there is no room left for any other religion than the official one to develop itself. In reality, things are very different, and to this day, outside of the recognised nonconformists, who have their own bishops and priests, and whose faith is recognised and acknowledged by the State, there are any number of sects, each more superstitious and each more powerful than the other in regard to the influence which they exercise over their adherents. These, though not numerous by any means, yet are actuated by such fanaticism that they are apt at certain moments to become subjects of considerable embarrassment to the authorities. Some are inspired by the conviction that the only means to escape from the clutches of the devil consists in suicide or in the murder of other people.

For instance, the Baby Killers, or Dietooubitsy, as they are called, think it a duty to send to Heaven the souls of new-born infants, which they destroy as soon as they see the light of day, thinking thus to render themselves agreeable to the Almighty by snatching children away from the power of the evil one. Another sect, which goes by the name of Stranglers, fully believes that the doors of Heaven are only opened before those who have died a violent death, and whenever a relative or friend is dangerously ill they proceed to smother him under the weight of many pillows so as to hasten the end. The Philipovtsy preach salvation through suicide, and the voluntary death of several people in common is considered by them as a most meritorious action. Sometimes whole villages decide to unite themselves in one immense holocaust and barricade themselves in a house, which is afterward set on fire.

An incident that occurred during the reign of Alexander II. is remembered to this day in Russia. A peasant called Khodkine persuaded twenty people to retire together with him into a grotto hidden in the vast forests of the government of Perm, where he compelled them to die of hunger. Two women having contrived to escape, the fanatics, fearing that they might be denounced, killed themselves with the first weapons which fell under their hand. It was their terror that they might find themselves compelled to renounce their sinister design, and thus fall again into the clutches of that Satan for fear of whom they had made up their minds to encounter an awful death. Even as late as the end of the last century such acts of fanaticism could be met with here and there in the east and centre of Russia. In 1883, under the reign of the father of the last Czar, a peasant in the government of Riazan, called Joukoff, burnt himself to death by setting fire to his clothes, which he had previously soaked in paraffin, and expired under the most awful torments, singing hymns of praise to the Lord.

Among all these heresies there are two which have attracted more than the others the attention of the authorities, thanks to their secret rites and to their immoral tendencies. They are the Skoptsy, or Voluntary Eunuchs, about which it is useless to say anything here, and the Khlysty, or Flagellants, which to this day has a considerable number of adepts and to which Rasputin undoubtedly belonged, to which, in fact, he openly owed allegiance. This sect, which calls itself “Men of God,” has the strangest rites which human imagination can invent. According to its precepts, a human creature should try to raise its soul toward the Divinity with the help of sexual excesses of all kinds. During their assemblies they indulge in a kind of waltz around and around the room, which reminds one of nothing so much as the rounds of the Dancing Dervishes in the East. They dance and dance until their strength fails them, when they drop to the floor in a kind of trance or ecstasy, during which, being hardly accountable for their actions, they imagine that they see Christ and the Virgin Mary among them. They then threw themselves into the embrace of the supposed divinities.

As a rule the general public knows very little concerning these sects, but I shall quote here a passage out of a book on Russia by Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace, which is considered to this day as a standard work in regard to its subject. “Among the ‘Khlysty,’” he writes, “there are men and women who take upon themselves the calling of teachers and prophets, and in this character they lead a strict, ascetic life, refrain from the most ordinary and innocent pleasures, exhaust themselves by long fasting and wild ecstatic religious exercises and abhor marriage. Under the excitement caused by their supposed holiness and inspiration, they call themselves not only teachers and prophets, but also Saviours, Redeemers, Christs, Mothers of God. Generally speaking, they call themselves simply gods and pray to each other as to real gods and living Christs and Madonnas. When several of these teachers come together at a meeting they dispute with each other in a vain, boasting way as to which of them possesses most grace and power. In this rivalry they sometimes give each other lusty blows on the ear, and he who bears the blows the most patiently, turning the other cheek to the smiter, acquires the reputation of having the most holiness.

“Another sect belonging to the same category and which indeed claims close kindred with it is the Jumpers, among whom the erotic element is disagreeably prominent. Here is a description of their religious meetings, which are held during summer in a forest and during winter in some outhouse or barn. After due preparation prayers are read by the chief teacher, dressed in a white robe and standing in the midst of the congregation. At first he reads in an ordinary tone of voice and then passes gradually into a merry chant. When he remarks that the chanting has sufficiently acted on the hearers he begins to jump. The hearers, singing likewise, follow his example. Their ever-increasing excitement finds expression in the highest possible jumps. This they continue as long as they can—men and women alike yelling like enraged savages. When all are thoroughly exhausted the leader declares that he hears the angels singing, and then begins a scene which cannot be here described.”

I have quoted this passage in full because it may give to the reader who is not versed in the details of Russian existence and Russian psychology the key to the circumstances that helped Rasputin to absorb for such a considerable number of years the attention of the public in Russia, and which, in fact, made him possible as a great ruling, though not governing, force in the country. In some ways he had appealed to the two great features of the human character in general and of the Russian character in particular—mysticism and influence of the senses. It is not so surprising as it might seem at first sight that he contrived to ascend to a position which no one who knew him at first ever supposed he would or could attain.

At the same time I must, in giving a brief sketch of the career of this extraordinary individual, protest against the many calumnies which have associated him with names which I will not mention here out of respect and feelings of patriotism. It is sufficiently painful to have to say so, but German calumny, which spares no one, has used its poisoned arrows also where Rasputin came to be discussed. It has tried to travesty maternal love and anxiety into something quite different, and it has attempted to sully what it could not touch. There have been many sad episodes in this whole story of Rasputin, but some of the people who have been mentioned in connection with them were completely innocent of the things for which they have been reproached. Finally, the indignation which these vile and unfounded accusations roused in the hearts of the true friends and servants of the people led to the drama which removed forever from the surface of Russian society the sectarian who unfortunately had contrived to glide into its midst.

The one extraordinary thing about Rasputin is that he was not murdered sooner. He was so entirely despised and so universally detested all over Russia that it was really a miracle that he could remain alive so long a time after it had been found impossible to remove him from the scene of the world by other than violent means. It was a recognised fact that he had had a hand in all kinds of dirty money matters and that no business of a financial character connected with military expenditure could be brought to a close without his being mixed in it. About this, however, I shall speak later on in trying to explain how the Rasputin legend spread and how it was exploited by all kinds of individuals of a shady character, who used his name for purposes of their own. The scandal connected with the shameless manner in which he became associated with innumerable transactions more or less disreputable was so enormous that unfortunately it extended to people and to names that should never have been mentioned together with him.

* * * * *

It must never be forgotten, and I cannot repeat this sufficiently, that Rasputin was a common peasant of the worst class of the Russian moujiks, devoid of every kind of education, without any manners and in his outward appearance more disgusting than anything else. It would be impossible to explain the influence which he undoubtedly contrived to acquire upon some persons belonging to the highest social circles if one did not take into account this mysticism and superstition which lie at the bottom of the Slav nature and the tendency which the Russian character has to accept as a manifestation of the power of the divinity all things that touch upon the marvellous or the unexplainable. Rasputin in a certain sense appeared on the scene of Russian social life at the very moment when his teachings could become acceptable, at the time when Russian society had been shaken to its deepest depths by the revolution which had followed upon the Japanese war and when it was looking everywhere for a safe harbour in which to find a refuge.

* * * * *

At the beginning of his career and when he was introduced into the most select circles of the Russian capital, thanks to the caprices and the fancies of two or three fanatic orthodox ladies who had imagined that they had found in him a second Savonarola and that his sermons and teachings could provoke a renewal of religious fervour, people laughed at him and at his feminine disciples, and made all kinds of jokes, good and bad, about him and them. But this kind of thing did not last long and Rasputin, who, though utterly devoid of culture, had a good deal of the cunning which is one of the distinctive features of the Russian peasant, was the first to guess all the possibilities which this sudden “engouement” of influential people for his person opened out before him and to what use it could be put for his ambition as well as his inordinate love of money. He began by exacting a considerable salary for all the prayers which he was supposed to say at the request of his worshippers, and of all the ladies, fair or unfair, who had canonised him in their enthusiasm for all the wonderful things which he was continually telling them. He was eloquent in a way and at the beginning of his extraordinary thaumaturgic existence had not yet adopted the attitude which he was to assume later on—of an idol, whom every one had to adore.

Photograph, International Film Service, Inc.

The Ex-Czar and His Family

* * * * *

He was preaching the necessity of repenting of one’s sins, making due penance for them after a particular manner, which he described as being the most agreeable to God, and praying constantly and with unusual fervour for the salvation of orthodox Russia. He contrived most cleverly to play upon the chord of patriotism which is always so developed in Russians, and to speak to them of the welfare of their beloved fatherland whenever he thought it advantageous to his personal interests to do so. He succeeded in inspiring in his adepts a faith in his own person and in his power to save their souls akin to that which is to be met with in England and in America among the sect of the Christian Scientists, and he very rapidly became a kind of Russian Mrs. Eddy. A few hysterical ladies, who were addicted to neuralgia or headaches, suddenly found themselves better after having conversed or prayed with him, and they spread his fame outside the small circle which had adopted him at the beginning of his career. One fine day a personal friend of the reigning Empress, Madame Wyroubourg, introduced him at Tsarskoie Selo, under the pretext of praying for the health of the small heir to the Russian throne, who was occasioning some anxiety to his parents. It was from that day that he became a personage.

* * * * *

His success at court was due to the superstitious dread with which he contrived to inspire the Empress in regard to her son. She was constantly trembling for him, and being very religiously inclined, with strong leanings toward mysticism, she allowed herself to be persuaded more by the people who surrounded her than by Rasputin himself. She believed that the man of whose holiness she was absolutely persuaded, could by his prayers alone obtain the protection of the Almighty for her beloved child. An accidental occurrence contributed to strengthen her in this conviction. There were persons who were of the opinion that the presence of Rasputin at Tsarskoie Selo was not advantageous for many reasons. Among them was Mr. Stolypine, then Minister of the Interior, and he it was who made such strong representations that at last Rasputin himself deemed it advisable to return to his native village of Pokrovskoie, in Siberia. A few days after his departure the little Grand Duke fell seriously ill and his mother became persuaded that this was a punishment for her having allowed the vagrant preacher to be sent away. Rasputin was recalled, and after this no one ever spoke again of his being removed anywhere. From that time all kinds of adventurers began to lay siege to him and to do their utmost to gain an introduction.

Russia was still the land where a court favourite was all-powerful, and Rasputin was held as such, especially by those who had some personal interest in representing him as the successor to Menschikoff under Peter the Great, Biren under the Empress Anne and Orloff under Catherine II. He acquired a far greater influence outside Tsarskoie Selo than he ever enjoyed in the imperial residence itself, and he made the best of it, boasting of a position which in reality he did not possess. The innumerable state functionaries, who in Russia unfortunately always have the last word to say everywhere and in everything and whose rapacity is proverbial, hastened to put themselves at the service of Rasputin and to grant him everything which he asked, in the hope that in return he would make himself useful to them.

A kind of bargaining established itself between people desirous of making a career and Rasputin, eager to enrich himself no matter by what means. He began by playing the intermediary in different financial transactions for a substantial consideration, and at last he thought himself entitled to give his attention to matters of state. This was the saddest side of his remarkable career as a pseudo-Cagliostro. He had a good deal of natural intelligence, and while being the first to laugh at fair ladies who clustered around him, he understood at once that he could make use of them. This he did not fail to do. He adopted toward them the manners of a stern master, and treated them like his humble slaves. At last he ended by leading the existence of a man of pleasure, denying himself nothing, especially his fondness for liquor of every kind. At that time there was no prohibition in Russia and, like all Russian peasants, Rasputin was very fond of vodka, to which he never missed adding a substantial quantity of champagne whenever he found the opportunity.