Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arena Sport

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

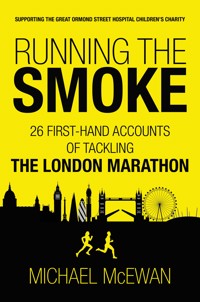

This updated edition features a new introduction, and an exclusive interview with long-distance runner Paula Radcliffe. It is the world's most iconic road race. It is twenty-six-point-two miles of iconic landmarks, cheers, tears, sweat, pain, courage, determination and inspiration. It is triumph over adversity on a colossal scale. It is the London Marathon - and it's an event unlike any other. Running The Smoke tells the story of what it's like to take part in this race in the most enlightening and enriching way possible: from the perspectives of twenty-six different people who have participated in it since its inception in 1981. Candid and inspiring if you are preparing for your first marathon or your 100th, Running The Smoke will give you the encouragement, insight and belief you need to cross that line.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RUNNING THE SMOKE

26 FIRST-HAND ACCOUNTS OF TACKLING

THE LONDON MARATHON

First published in Great Britain in 2016 byARENA SPORTAn imprint of Birlinn LimitedWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.arenasportbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Michael McEwan, 2016

ISBN: 9781909715387 eBookISBN: 9780857903327

The right of Michael McEwan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, Edinburghwww.polarispublishing.com

Printed in Great Britain by Clays, St Ives

For Juliet,and the three little ones who’llnever run a marathon but are withus every step of the way.

‘The greater the obstacle,the more glory in overcoming it.’Molière

‘When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life;for there is in London all that life can afford.’Samuel Johnson

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE LONDON MARATHON

ONE: Dick Beardsley

TWO: Lloyd Scott

THREE: Sir Steve Redgrave

FOUR: Sadie Phillips

FIVE: Claude Umuhire

SIX: Steve Way

SEVEN: Dave Howard

EIGHT: Nell McAndrew

NINE: Kannan Ganga

TEN: Jamie Andrew

ELEVEN: Jo-ann Ellis

TWELVE: John Farnworth

THIRTEEN: Guy Watt

FOURTEEN: Andy Rayner

FIFTEEN: Dale Lyons

SIXTEEN: Liz McColgan-Nuttall

SEVENTEEN: Phil Packer

EIGHTEEN: Luke Jones

NINETEEN: Rob Young

TWENTY: Michael Lynagh

TWENTY-ONE: Claire Lomas

TWENTY-TWO: Dave Heeley

TWENTY-THREE: Laura Elliott

TWENTY-FOUR: Michael Watson

TWENTY-FIVE: Charlie Spedding

TWENTY-SIX: Jill Tyrrell

26 TIPS FOR RUNNING THE LONDON MARATHON

26 LONDON MARATHON FUNDRAISING TIPS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT GREAT ORMOND STREET HOSPITAL

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

American Dick Beardsley, left, and Inge Simonsen of Norway cross the finish line together to win the first-ever London Marathon in 1981. Getty Images

Lloyd Scott poses near Tower Bridge during his attempt to complete the 2002 London Marathon wearing a full deep-sea diving suit. Getty Images

Sir Steve Redgrave, wearing the No.1 bib, waves to the crowd during the 2001 London Marathon. Getty Images

Sadie Phillips and her boyfriend, Jon, ran the 2015 London Marathon after Sadie defeated cancer not once but twice.

Claude Umuhire, a survivor of the Rwandan genocide as a child, ran the 2015 London Marathon only a matter of years after sleeping rough on the streets of the capital.

Steve Way weighed close to seventeen stone before he discovered a talent for running.

Steve Way finishing the 2014 London Marathon. He was the third fastest Brit that year and, as a result, qualified for the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow later that year.

Dave Howard ran the 2014 London Marathon in memory of his best friend, Matthew West, who committed suicide a year earlier.

Kannan Ganga, right, ran the London Marathon in 2015 after his partner, Satori Hama, left, passed away on the morning of the 2014 race.

Nell McAndrew with her mum, Nancy, ahead of the 2007 London Marathon which they ran together. Getty Images.

Jamie Andrew ran the 2002 London Marathon, just three years after having all four limbs amputated following a climbing accident in the French Alps.

Jo-ann Ellis ran the 2014 London Marathon in memory of her son, Jake, who died from a rare form of cancer aged just five.

Jake Ellis.

Football freestyler John Farnworth completed the 2011 London Marathon whilst juggling a football the entire way. He didn’t drop the ball once, kicking it an estimated 90,000 times! piQtured

Dale Lyons is one of a small band of runners to have completed every single London Marathon since its inception in 1981.

Guy Watt, pictured here with his daughters, ran the 2015 London Marathon just over a year after he was almost killed in a horror car crash.

Andy and Elaine Rayner with their son, Sebastian.

Liz McColgan takes the tape to win the 1996 London Marathon. Getty Images

Former Army major Phil Packer defied doctors’ expectations when he completed the 2009 London Marathon.

Watching the 2014 London Marathon put novice runner Rob Young on the path to becoming one of the world’s top ultra-marathon runners. Chris Winter

Look closely – Luke Jones (No.27588) ran the 2014 London Marathon . . . barefoot. MarathonFoto

Australian rugby union legend Michael Lynagh, left, completed the 2013 London Marathon alongside Sky Sports rugby presenter, James Gemmell. MarathonFoto

Claire Lomas closes in on the finish line during her London Marathon challenge in 2012. Robin Plowman

Dave Heeley has completed the London Marathon more than a dozen times since 2002, despite being registered blind.

Paul and Laura Elliott had a wedding day to remember when they tied the knot during the 2015 London Marathon.

Former boxer Michael Watson crosses the finish line after completing the 2003 London Marathon in 6 days, 2 hours, 27 minutes and 17 seconds.

A delighted Charlie Spedding crossing the finishing line to win the 1984 London Marathon.

Jill Tyrrell ran the 2006 London Marathon, just a matter of months after being caught up in the 7/7 terrorist attacks in London. ‘I had the motivation of wanting to prove to the bombers that they didn’t, couldn’t and never would win,’ she said.

PREFACE

EVERYTHING HURTS.

The soles of my feet, my shins, my calves, my knees, my thighs, my hamstrings, my hips, my chest, my shoulders, my forearms, my head.

Everything.

I might be imagining it but I think I can feel each individual hair pulsing in the crown of my skull in time to my heartbeat and, just for good measure, I’ve even managed to get sunburnt.

Suddenly, a realisation hits me: I’m crying. At least I think I am. I sweep the back of my hand across my cheek to make sure. At first, the friction of dry skin on dry skin feels as though I’m dragging sandpaper across my face but then I feel them. Tears. Warm, humiliating, inexplicable tears. Great.

I’m exhausted. I’m dehydrated. My shorts and T-shirt are rinsed in sweat.

I’m a mess.

There’s not much I can do about any of that right now, though, so I hobble forward to collect my medal. A volunteer in her fifties picks it up, opens the lanyard and is ready to pass it over my head and down around my neck when she hesitates. Right then, I realise I’m not just shedding a few tears. I’m sobbing almost uncontrollably, like a scolded child.

Somehow, I manage an embarrassed laugh. ‘I’m really sorry,’ I say. ‘It’s just that I’ve been waiting for this moment for most of my life.’ A trifle melodramatic but not entirely untrue, either.

The woman smiles, continues and, as she adjusts the way the ribbon sits on my neck, she pats me on the shoulder and says: ‘Well, you’ve earned it.’

I force a grateful nod of acknowledgement and shuffle along, studying my medal as I go. As I gaze at it, I feel almost hypnotised and, in that instant, every pain evaporates at once. Right at this moment, I feel only one thing: pride. Immense, immeasurable, irresistible pride.

It has taken me years to get to this point and, for good measure, a further four hours, forty-one minutes and fifty-nine seconds to complete the punishing but magnificent course. But it has all been worth it.

It’s Sunday, 13 April 2014 and I have just run the London Marathon.

*

I THINK I’m quite like most other runners in that I don’t run for pleasure.

It is not, in my opinion, a particularly enjoyable activity. Putting one foot in front of the other as fast as you can – what’s to enjoy?

Instead, I run for fulfilment. I do it for the rush, the buzz, the sense of accomplishment as you cross the finishing line. Nothing compares to that feeling. Your veins pop, crackle and fizz. Your senses jingle, your nerves jangle. You feel ten feet tall and entirely invincible. It’s unique. It’s brilliant. It’s addictive.

I first encountered it at school. I ran throughout my time there, although not to any great standard. Whilst most of my classmates dreaded the annual December cross country race, I looked forward to it. I never won it. Never even came close. But I always got what I wanted out of it: that feeling.

I entered my first timed race at the age of twenty-two – the Great Scottish Run in Glasgow – and subsequently took part in numerous 10k events.

My first marathon was Loch Ness in September 2011. I followed that up with the Berlin Marathon exactly twelve months later. But I wanted more. I wanted London.

As a little boy, I used to watch it on television every year sitting in the living room of our family home. I loved it from the moment I first saw it. It leapt off the screen. The elite runners left me dumbstruck. The fancy dress worn by the fun runners made me smile. The anthem at the beginning of the BBC coverage made my heart swell. More than anything, I loved its tangible camaraderie and warmth. The London Marathon is so much more than a sporting event. It is entirely transcendent.

It was, therefore, inevitable I would run it one day. It was just a question of when. For me, that ‘when’ was that sunny Sunday in April 2014. Did it live up to my expectations? More than. Did it hurt? Oh God, yeah. Do I want to do it all over again? Like you wouldn’t believe.

Standing on the start line that morning, I took a moment to look around at all of the other runners. More than 36,000 people took part that day and, like me, all were there for a reason. Mine was to complete a lifetime ambition. For others, it was to run in memory of a loved one, to celebrate overcoming an illness, to raise money for a charity, to lose weight, and so on and so forth.

That’s where the idea for this book first crystallised. I decided I wanted to find twenty-six inspirational people who have completed the London Marathon and find out more about their motivations for getting to the start line as much as their experiences between there and the finish.

In my research, I have spoken to some truly wonderful people who have, truthfully, left a profound and lasting impression on me. It is so easy to get cocooned within the minutiae of our own lives, isn’t it? The only way to maintain an anchor-point on reality and understand the true context of our ‘troubles’ is to talk to others. It’s an underrated medium in this era of ‘text-speak’ and digital communication.

Some of the stories that follow are funny. Others are remarkable. More still are illuminating. And some, I’m afraid to say, are impossibly sad. Each and every one has been my immense privilege to hear at their source and share herein with you.

Whether you have run the London Marathon before, dream of running it in the future, or simply just enjoy reading about ordinary people doing extraordinary things, I hope you will draw inspiration from what follows. I know I have.

Enjoy the book.

Michael McEwanApril 2016

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE LONDON MARATHON

EVERY race starts somewhere.

Incongruous as it may seem, the London Marathon can trace its own beginnings to a pub in south-west London. It was in the Dysart Arms, adjacent to Richmond Park, that plans for what would become one of the world’s most iconic running events were hatched in 1979.

The bar was the home of the historic Ranelagh Harriers Running Club. Its members would meet there after their Wednesday evening training sessions to recall, as the club’s own website puts it, ‘how fast they ran when in the full flush of youth and dream of new challenges to conquer’.

Dating back to 1881, the Ranelagh Harriers Running Club is one of the oldest athletic clubs in the UK. Indeed, it was one of the founder members of the English Cross Country Union in 1883. Originally based out of the Green Man bar on Putney Heath in south-west London, the club moved into an old pavilion at the back of the Dysart Arms in the 1930s, where it has been based ever since.

Because of the size and popularity of the club, members of the Ranelagh Harriers have, over the years, become regulars in some of the most famous races in the world, never mind the UK. One of its most industrious and enterprising members in the 1970s was Steve Rowland, the manager of a small running shoe shop in Teddington called ‘Sweatshop’. The shop was co-owned by Chris Brasher, the winner of the men’s steeplechase gold medal in the 1956 Olympic Games, and John Disley, a bronze medallist in the steeplechase four years earlier in Helsinki.

Described as a ‘crazy runner who was always up for a new challenge’, Rowland’s competitive instincts were piqued in 1978 when he read an article about the success of the 1977 New York Marathon. The piece told how almost 4,000 people completed a 26.2-mile circuit through all five of the Big Apple’s boroughs – Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Staten Island – cheered on by tens of thousands of well-wishers who lined the route.

The story captured Rowland’s imagination to such an extent that he decided to enter the race for himself in 1978. He even went so far as to place a small advert in The Observer and Athletics Weekly, the pre-eminent running publication of the day, for other runners to join him. Around forty people took him up on the invitation, including half a dozen of his fellow Ranelagh Harriers.

Neither Rowland nor any of his companions troubled the prize board. The famous American long-distance runner Bill Rodgers won the men’s race, the third of four consecutive victories for the man they called ‘Boston Billy’, whilst the late Grete Waitz from Norway became the first non-American to win the women’s race, clocking a new course record in the process. However, the British contingent returned home with the next best thing: a raft of memories to last a lifetime.

Unwinding in the Dysart Arms after their Wednesday training sessions, their conversations would regularly turn to their shared experiences in New York. It was the infectious enthusiasm of four of the New York runners that reportedly aroused the interest of Brasher.

By now retired from competitive athletics, Brasher had made a name for himself as a successful journalist and broadcaster. Hearing the tales of the New York Marathon, and sensing a story, he entered the race in 1979. He convinced The Observer, for whom he had previously served as sports editor, to pay for his trip and persuaded Disley to join him, too.

Just like their club mates a year earlier, the pair found the whole experience utterly captivating and, seven days later, Brasher recalled the race in articulate, lucid detail in his newspaper column.

He wrote: ‘Last Sunday, in one of the most violent, trouble-stricken cities in the world, 11,532 men, women and children from forty countries of the world, assisted by 2.5m black, white and yellow people, Protestants and Catholics, Jews and Muslims, Buddhists and Confucians, laughed, cheered and suffered during the greatest folk festival the world has seen.’

He concluded: ‘I wonder whether London could stage such a festival? We have the course . . . but do we have the heart and hospitality to welcome the world?’

Just 517 days later, on 29 March 1981, he got his answer.

*

IT was not as though London didn’t already have a marathon. It had, in fact, a successful and well-established one in the form of the Polytechnic Marathon.

The ‘Poly’ was introduced when the 1908 Olympic Games were relocated to London in the wake of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 1906. It was a disaster that killed more than 100 people and required funds intended for the Rome Olympics to be used instead for the reconstruction of Naples.

The race was organised by the Polytechnic Harriers, the athletics club of the Polytechnic at Regent Street in London, which is now the University of Westminster.

At that time, there was no set distance for a marathon. It was simply a long race in the region of 40km. The Polytechnic Harriers mapped out a course that started in front of the Royal Apartments at Windsor Castle and ended on the track at White City Stadium – the since-demolished home of the 1908 Games – in front of the Royal Box. All in, the course measured 26 miles plus an extra 385 yards. They didn’t know it at the time but the Polytechnic Harriers had just created a new uniform standard distance for a marathon.

That first event really captured the imagination of the public, not least because of its dramatic finish. Dorando Pietri of Italy took the lead with just two kilometres to go but, as he entered the stadium for the final 400 metres, he took a wrong turn and was redirected by umpires. Suddenly, he fell to his knees in front of a watching crowd of some 75,000. The umpires helped him to his feet but he fell again. And again. And again. And again. Each time, he was helped to his feet and, somehow, he managed to cross the line in first place. Of the two hours, fifty-four minutes and forty-six seconds he spent running that day, he used up ten minutes to complete that final lap.

Pietri finished ahead of American runner Johnny Hayes but, when the US team lodged an official complaint over the assistance the Italian runner received from the umpires, Pietri was disqualified, handing the gold medal to Hayes.

The Italian’s fate became headline news. As compensation, Queen Alexandra gifted him a gilded silver cup, whilst the great novelist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, commissioned by the Daily Mail to produce a special report on the race, wrote: ‘The Italian’s great performance can never be effaced from our record of sport, be the decision of the judges what it may.’

Acknowledging the interest generated by Pietri, Hayes and the Olympic marathon, the Sporting Life newspaper commissioned a spectacular trophy – made at a cost of £500, roughly £50,000 in today’s money – to be contested in an annual international marathon that would be second in importance only to the Olympics. The Polytechnic Harriers were asked to organise the event and so it came to pass that, on 8 April 1909, the first Polytechnic Marathon was staged.

It continued to use a course spanning 26 miles and 385 yards, which, in 1924, became adopted as the international standard for all marathons.

For a long time, the Poly went from strength to strength. It even survived, in 1961, the loss of the support of the Sporting Life.

What it couldn’t survive, however, was evolution. The Windsor-to-Chiswick route that it had used since 1938 fell victim to the London traffic, restricting the race to the Windsor area from 1973. The world record-setting performances that had been so common in the 1950s and 1960s tailed off, too, as mass marathons and big-money events – such as the New York Marathon – took off.

By the time that Chris Brasher’s new London Marathon took place for the first time on 29 March 1981, the Poly was in terminal decline. It survived under the auspices of various different bodies until 1996 when it was staged for the last time.

The Poly’s diminished status was in stark contrast to the immediate popularity of the London Marathon. Having secured the support of top shaving brand Gillette, which pledged to back the fledgling race to the tune of £75,000 per year for the first three years, Brasher established charitable status for his event. He also set out six goals in an attempt to emulate the success of the New York Marathon and others like it. Those goals were:

•To improve the overall standard and status of British marathon running by providing a fast course and strong international competition;

•To show mankind that, on occasions, they can be united;

•To raise money for sporting and recreational facilities in London;

•To help boost London’s tourism;

•To prove that ‘Britain is best’ when it comes to organising major events; and

•To have fun, and provide some happiness and sense of achievement in a troubled world.

Over 20,000 people applied to run in that first race. Of those, 7,747 were accepted in line with restrictions placed upon the race by the police. The vast majority crossed the finishing line on Constitution Hill between Green Park and Buckingham Palace. Competitors ranged in age from fifteen to seventy-eight and, at 9 a.m. on a wet Sunday morning in Greenwich Park, in the south-east of London, they were sent on their way by the boom of a twenty-five pound cannon.

Two hours, eleven minutes and forty-eight seconds later, the tape stretching across the finishing line was burst in scenes almost as dramatic as the conclusion to the Olympic Marathon seventy-three years earlier.

American Dick Beardsley and Inge Simonsen of Norway had been separated by little more than a few paces the entire race. Passing the Cutty Sark, crossing Tower Bridge, leaving St Paul’s Cathedral in their wake – they were side by side almost the entire way. As they closed in on the finishing line, they passed Buckingham Palace and turned onto Constitution Hill where, picking up the pace for one final burst, they spontaneously joined hands and burst through the tape in unison.

The incident passed immediately into sporting folklore as the ‘Hand of Friendship’. Two men, two competitors, living and training over 3,000 miles apart, joining forces to complete a remarkable feat of sporting endurance in the most sportsmanlike of ways – it was precisely the launch pad the London Marathon needed. Completing a near-perfect first edition was the sight of Joyce Smith, a forty-three-year-old mother of two, breaking the British marathon record to win the women’s race. Smith’s time of 2:29:57 was also the third fastest marathon time ever recorded by a woman.

These scenes and many more like them were beamed directly into homes across the United Kingdom by the BBC, with stories of Beardsley and Simonsen’s iconic win, in particular, relayed by news outlets around the world.

The following year, over 90,000 people applied to take part in the race. The entry restrictions were relaxed to allow 18,059 to do so.

Since then, the popularity of the London Marathon has grown almost year on year. In 2006, it was one of the five founding members of the World Marathon Majors series along with New York, Chicago, Boston and Berlin. As of 2016, more than one million runners have completed the race.

A host of categories have also been introduced to cater for the variety of runners that the race attracts. Indeed, in 1981, fewer than five per cent of all participants were women, while there were no wheelchair athletes, no Mini London Marathon race for children, and certainly no runners in fancy dress.

Today, it’s a different story altogether. The proportion of female competitors has grown markedly to the extent that women accounted for almost thirty-seven per cent of all those who ran in 2015. There are also separate men’s and women’s wheelchair races. The men race in two separate classifications as outlined by the International Paralympic Committee: T53/54, for athletes with normal arm and hand function and either no or limited trunk function or leg function, as well as T51/52, for athletes with activity limitations in both lower and upper limbs. At present, the women’s wheelchair race is contested only by athletes in the T53/54 class.

There are also races for athletes with other lumbar impairments that meet with the T42, T44, T45 and T46 IPC classifications, as well as athletes with visual impairments, so defined by the T11, T12 and T13 classifications.

A junior race, the Mini London Marathon, was introduced in 1986. It spans the last three miles of the official London Marathon course – taking in the route from Old Billingsgate to The Mall – and is open to those aged between eleven and seventeen. There are also four junior wheelchair races along the same course, open to children under seventeen years of age.

However, arguably the most celebrated and iconic aspect of the London Marathon is the philanthropy of its so-called ‘fun runners’. It is reckoned that as many as three-quarters of all of those who take part in the race do so to raise money for charity, with more than £50 million raised for good causes every single year. The event itself holds a Guinness World Record for one-day charity fundraising, a record it has broken each year for the most part of the last decade.

In total, over £770 million has been raised for charity by those running in the London Marathon, whilst in the thirty-five years since it was founded, The London Marathon Charitable Trust has used profits from the race and other London Marathon events to make grants exceeding £57 million to more than 1,000 organisations.

The BBC continues to broadcast the event annually, although it is now syndicated into homes in almost 200 countries. Roughly three-quarters of a million people, meanwhile, line the streets of the route to cheer the runners on.

From singlets, to fancy dress, to full deep-sea diving suits, the widest imaginable spectrum of fashion has been worn in the London Marathon since its inception. It is a colourful, dramatic, inspirational and awe-inspiring sight to see.

Equally, it is an unforgettable, emotional, invigorating and often life-affirming event to participate in. As you will discover reading this book, running the London Marathon is both a deeply personal decision and a community-forming experience. It unites people in a way that few other sporting events can, whilst bringing out the very best in society, whether that’s those pounding the streets of the capital in the race itself or the crowds willing them on from the sidelines.

It is, in the simplest of terms, a race that is truly good and decent from both the top down and the bottom up.

Not bad going for an event that was discovered at the bottom of a pint glass.

CHAPTER ONE

DICK BEARDSLEY

Together with Inge Simonsen of Norway, Dick Beardsley was the joint winner of the inaugural London Marathon. The Minneapolis-born runner, who had celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday just eight days before the race, completed the course in a time of 2:11:48.

EVEN now, decades later, I still get emotional when I think back to that wet, breezy day in London.

I didn’t know it at the time but 29 March 1981 would transform my career forever. I woke that morning as a full-time long-distance runner of a pretty good standard and later went to bed as the winner of a marathon. It was one of the most important, significant days of my life.

My London Marathon story, however, begins 4,000 miles away and many years earlier near Minneapolis. I was quite a shy kid at school but, like every other young guy, I wanted to be popular with girls. They, in turn, seemed to want to talk pretty much exclusively to the guys who wore the high school letterman jackets, the jackets which separated the kids that were good at sports from those that, well, weren’t.

I set my sights on becoming one of those guys, so I tried out for the school’s American football team. There was just one problem: I weighed only 130 pounds. That’s too light by half. I lasted one practice.

Instead, I switched my focus to running. It came quite naturally to me, although I was far from the top dog on the school’s cross country team. I think I got by on my enthusiasm as much as anything else and my coach seemed to like that about me. He let me run in enough race meets to qualify for one of the jackets I so desperately craved. I was absolutely elated!

By the time I left high school, running had become a big part of my life, so I joined my college team. I continued to combine competing with my studies but, even then, I had no intention of pursuing running as a career. In fact, when I graduated with an Associates Degree in Agriculture, I actually became a dairy farmer for a while. Running was a hobby, a passion, but nothing more.

It wasn’t until August 1977 that I entered my first marathon, the Paavo Nurmi Marathon in Hurley, Wisconsin. It had been on the calendar for eight years by that point and was pretty popular. More to the point, it was just four hours’ drive away from where I lived, so it was nice and convenient.

I ran it in 2:47:14. Not bad for a first-timer but not that great either. I figured I could run faster – and I was right. In subsequent marathons, I got steadily quicker: 2:33:22, 2:33:06, 2:31:50.

Before I knew it, I was becoming a really good runner and, in 1980, I noticed that the qualification time for the US Olympic Trials Marathon was 2:21:56. ‘Wow,’ I thought, ‘that’s just ten minutes faster than my best time.’ I entered the Manitoba Marathon in Canada and met the qualification standard with only two seconds to spare.

I ran the trial in 2:16:01, continuing a streak of new personal records that ultimately spanned forty-six months and thirteen marathons. It wasn’t enough, though. I finished in sixteenth place and had to watch the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow from my home in Minnesota.

It was disappointing to miss out. Of course it was. But I was encouraged by my performance. I had seen enough to give me the belief that I could get better. Much better. What I needed was to dedicate myself to running full-time. If I did that, I told myself, there was no reason why I couldn’t qualify for the 1984 Olympic Games. Besides, they were taking place in Los Angeles. Running in the Olympics on home soil in front of a partisan crowd – it became more than a dream; it became my goal.

There was just one problem. Professional running wasn’t a particularly lucrative industry. I still had to find a way to keep a roof over my head, pay bills and so on. Without support, that’s something I’d never have been able to afford.

As it turned out, I couldn’t have picked a better time to try to make it as a pro. America was in the midst of a real running ‘boom’ in the late seventies and early eighties. The sport was massively increasing in popularity and I was fortunate enough to secure some backing from New Balance, one of the leading running shoe manufacturers. I’ve been told they were on the lookout for the next Bill Rodgers, one of America’s top distance runners and a winner of four Boston Marathons, including three in a row from 1978 to 1980. Luckily, New Balance saw something in me that they seemed to like and, with their sponsorship and support, I was able to become a full-time runner. I could train and prepare for races without having to fit it all around a job. It was an incredible opportunity.

It also opened up a lot of doors, London being one such example. You see, as well as being the organiser of the first London Marathon, Chris Brasher was also a European distributor for New Balance shoes. It was early in 1981 when he called the New Balance global headquarters in Boston, Massachusetts, to ask if they had any athletes that they would be interested in sending over to compete in his new race. They got in touch with me and said ‘Hey, Dick. How would you like a free trip to London?’

It was an easy ‘yes’. It was just too good an opportunity to turn down. For one thing, I’d never been to London before and it was somewhere I’d always wanted to visit. I mean, come on! It’s one of the greatest cities in the world! Equally, though, I was excited at the prospect of taking part in the first-ever London Marathon. Obviously, I didn’t have a sense at the time of just how big an event it would go on to become – nobody did – but something told me that it would be a special, memorable occasion.

From a ‘form’ point of view, I was confident about my prospects. In January 1981, I finished runner-up in the Houston Marathon with a new personal best time of 2:12:48. Less than a month later, I raced in Beppu, Japan, where I was third, crossing the line in 2:12:11. I was feeling good and feeling sharp. I was also young, so I recovered quickly, which was just as well given that London came only a month after Beppu.

I arrived in England about a week or so before the race. I was keen to acclimatise properly but I also wanted to make the most of the opportunity to see the city. I did all the typical things a tourist would do, went to all of the popular sights and landmarks, that kind of thing. I remember being a little overwhelmed by it all at first. It was so big and fast-moving, whereas I was just a kid from a quiet little town in Minnesota. It was a dramatic change of pace. However, what struck me most were the people, particularly the younger people in their late teens or early twenties. They wore these incredible, outlandish clothes and many had bright colours in their hair. I had never seen anything like them in my life. It’s funny what you remember. To this day, I can still see some of their faces. They were all so friendly, though. Not just the flamboyant kids; all the people. Everyone was nice, welcoming, accommodating. I was thousands of miles from where I grew up but, strangely, I felt right at home almost immediately.

I had a lot of fun that week but, equally, I made sure not to do too much. I have always found the week before a race quite difficult. The main bulk of your training, which has been so much a part of your life for the weeks and months immediately prior, is over and you have drastically reduced your mileage to ensure you arrive at the start line in peak condition. Fit, healthy, ready to go, not over-prepared. It’s a delicate balance and, more often than not, I felt like a caged tiger for much of the forty-eight to seventy-two hours before a race. London was no different. I just wanted to get started.

As excited as I was to take part, however, there were others who were very sceptical about the London Marathon. In fact, in the days leading up to it, I remember reading a newspaper, which seemed to be of the belief that the race wouldn’t be a success. There was a bit of negativity towards Chris Brasher and the other race organisers, which I thought was both very unfortunate and unfair. On top of that, the forecast was for cold, wet conditions. ‘Nobody will come out to cheer the runners on,’ the editorial insisted. How misinformed a piece it would prove to be.

I was put up in a small hotel close to the middle of the city. Things were a lot different then to the way they are now. These days, the top runners are all exceptionally well looked after. As well as some of the best hotel rooms in London for them and their entourage, they are also given large appearance fees to take part. In 1981, there were no such incentives for those of us who were expected to contend for the win. Don’t get me wrong, my hotel was nice enough but, well, here’s the deal: I’m a tall guy; my bed was small. I had to sleep in the foetal position just to stay on the mattress! But it was no big deal. I was just delighted to be there and tickled pink that somebody clearly wanted me there enough that they picked up my air fares and covered the cost of my accommodation. They even gave me enough money for a few hamburgers a day, which I remember being quite excited about!

Hamburgers, though, are really not the best things to be eating in the days leading up to a marathon, so I instead remember that I went out for dinner by myself the night before the race for some spaghetti and meatballs. Again, it’s probably not the ideal prep food but it had plenty of carbohydrates, so it suited me just fine.

The morning of the race dawned and I was picked up and taken by a courtesy car from my hotel to the start line in Greenwich Park. There was real excitement in the air. Unfortunately, there was also some rain. It wasn’t torrential by any means but it was drizzly enough that you got wet through pretty quickly, particularly as there was nowhere to go to stay out of it. I managed to spot a sponsors’ tent, though, and hung out in there until it was time to set off.

There were a lot of spectators around the start line. I guess they were there out of curiosity as much as anything else. They wanted to catch a glimpse of this new event, to see what it was all about. As we gathered for position ahead of the gun going off, I took a look around at the competition. England had some fabulous runners at that time and I remember thinking that we were in for quite a race.

The start back then was slightly different to what it is now. For one thing, we had to exit the park out of a gate just to get onto the first part of the route! Not only that, we took a lot of twists and turns and corners. Way more than you would usually have and, certainly, far more than the race has these days.

Now, let me give you an insight into my race day tactics. I never raced a marathon over the first half of the course. To me, that was always about finding my rhythm, getting a good flow going and trying to ensure that I stayed at the front of the pack or as close to it as possible. If you get that bit right, the second half of the race is where marathons are either won or lost.

Halfway in London is just after that famous moment where you cross Tower Bridge. It was shortly after that, as we were making our way towards the Isle of Dogs, when I decided to make my first move. There must have been around eight of us in the leading pack at that point and I can remember thinking to myself, ‘There are too many people here. I’m going to need to break this up a bit.’ So, I made a burst. Only Inge Simonsen responded and came with me.

It was actually a good thing that he did. That next part of the race went through what was, at that point, an old, industrial part of the city. It’s different now, of course. It’s actually one of the most beautiful parts of the race these days, in my opinion. But back then, it was quite old, run down and didn’t really have many spectators out there cheering you on. That was big for me. I have always been someone who has responded well to people cheering me on and willing me to do well, push harder, run faster, that sort of thing. I guess you could say that I enjoy other people’s company, so when Inge came with me on that break, it turned out to be for the best. It kept me focused and gave me somebody to bounce off when there was really nobody else out there.

We stayed on each other’s shoulders for the next eight miles or so and it was around the twenty-one-mile mark, as we went past Tower Bridge again, towards Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament, that we really started to race – and I mean race. When I made a move, Inge responded. When he made a counter-move, I kept pace. It went on like that for the next few miles. What complicated matters, though, was the condition of the road. Back then, that area was all old cobblestone paving, which obviously isn’t the ideal surface for runners. It’s so uneven that it really requires you to pay close attention not just to where your feet are landing but where you strike off from, too. However, when you add in a lot of rain, it becomes truly treacherous. The slabs just get so slippery that all you want is to try to find an even area where you can move freely and without putting too much strain on yourself.

Plus, at that stage of a marathon, the very last thing you want to have to worry about is wet cobblestone paving. It really wasn’t ideal! Still, we continued to press. We both badly wanted to win, so we pushed and we pushed and we pushed.

With about two or three miles to go, the crowd suddenly got really big and everyone started going crazy. I had never heard noise like it before. It was deafening. I can still feel the adrenaline surging through me as I soaked it in. It gave me a fresh burst of energy to kick on and press for the finish line. Clearly, it had the same effect on Inge. I couldn’t shake him and he couldn’t shake me. There was nothing between us, nor had there been for most of the way.

Then something really strange happened. It occurred to me that, you know what? We both deserve to win this race. It was clear at that point that either one of us was going to as we were so far ahead of the chasing pack. But having run so well together for almost twenty-six miles, the thought flashed through my mind that it would be sad if one of us was to lose.

I turned to Inge and said, ‘So, what do you think? Are we going to duke this out until the end or do you want to go together?’

He said something back to me but, in all honesty, I couldn’t make it out. He might have said, ‘Sure, let’s race,’ or ‘Okay, let’s do this together,’ but, in that moment, with the noise of the crowd ringing in my ears, I couldn’t work it out so I figured it was best to just work on the assumption that he wanted to race all the way in.

With a few hundred yards to go, I kicked hard for the line and, again, Inge came back at me. We were giving it absolutely everything. Then, all of a sudden, with just twenty metres to go, he reached over to me, grabbed my arm and lifted both his arms and mine into the air. It was instinctive. It was wonderful. And it was right. We burst through that tape at exactly the same time as one another.

It was the first marathon I’d ever won and I was overjoyed but even more so because of the way it happened. It truly was one of the great thrills of my career to share it with Inge.

I didn’t actually know him before that day. I mean, sure, we’d raced in the same events a couple of times but that was the extent of our relationship. He was in Norway; I was in Minnesota – when would our paths ever cross outside of a race? However, since that day, we have become great friends. I even ended up going to Oslo to race against him in a half-marathon not long after our battle in London. That’s how much our duel captured the imagination of the public.

I think that was partly down to the fact that, the day after the race, pictures of us crossing the finishing line together appeared in newspapers all around the world. People acclaimed it as a great example of sportsmanship, which I guess it was. It wasn’t some premeditated, deliberate thing. It was just the product of an unspoken but mutual respect between two athletes who appreciated what each other had just gone through for the last twenty-six miles or so. It was real. It was genuine. It was authentic. I suppose people liked that about it. Heck, even I like that about it! I’ve since watched the footage back on several occasions and I get goose bumps every time. I also wonder how I could ever have run that fast but that’s a different story!

After the race, we had various media commitments to fulfil before attending a banquet hosted by the organisers and attended by sponsors, guests and so on. I got the feeling that night that everybody there knew they were on to something truly special with the race. It was as if they all realised simultaneously that it had the potential to become one of the biggest and most influential marathons in the world. There was a real sense of accomplishment and pride in that room and rightly so.

When I finally got back to my hotel, I wanted to phone home and share my good news with my parents. Remember, this was in the days before mobile phones and the internet, so people had to rely on other means to share news, means that would probably be considered incredibly primitive these days! However, there was just one problem: I didn’t have enough money on me to pay for the call! I had to try to reverse the charges and hope they would pick up. Luckily, they did.

It was my mum who answered and I can vividly remember saying, ‘Mum, mum – I did it! I won! I won the London Marathon!’ Well, she just screamed. She screamed and screamed and screamed down the handset. She was so pleased she burst into tears. She passed the phone to my dad and his reaction was just the same. It’s an incredible feeling when you make your parents proud of you. There are few things in life that compare to it.

When I flew back to the States, the reception that greeted me as I landed was incredible. I arrived at Minneapolis airport shortly before midnight and there must have been a couple of hundred people waiting for me at the gate. They were all cheering and waving and holding up banners. They had even brought along the kids from the orchestra section of the local high school to play some songs, including the theme from Chariots of Fire. It was a buzz that I can’t even begin to find the words to describe. Whatever ones I’d choose wouldn’t do it justice, believe me!

People often ask me how my prize money for winning that race compares with the prize money on offer for the winners today. That’s easy because I didn’t get any. In fact, there wasn’t any prize! Inge and I were given a bottle of Champagne to share and were later sent these really beautiful gold-plated medals. But, no, there was no money, new TV set or anything like that. I honestly didn’t care, though. I still don’t. I was fortunate enough to be invited to one of the world’s great cities to compete in – and win – the first edition of what has become one of the world’s most important running events. No amount of money, nor anything else for that matter, can compare with that. I’ve run faster times, I’ve set course records and I’ve won other races outright, but the 1981 London Marathon has always held a very special place in my heart and it always will.

I went back to the London Marathon in 2015, but as a spectator rather than a competitor. My wife Jill and son Christopher were taking part, so I went to cheer them on. It was interesting to see it both through the eyes of and in the company of the spectators. I was able to appreciate the race on an entirely different level. You can’t help but be struck dumb by the kindness of the people who stand there for hours and hours on end, cheering on every single runner who comes through. Whether it’s one of the elite competitors or somebody struggling wilfully to complete the race in less than eight hours, they are roared on with the same vigour and intensity. It’s so genuine, too. They might be total strangers, from completely opposite backgrounds and may never cross paths ever again but, for that brief moment in time, they are united. They become a team. Runner and supporter. Supporter and runner. Working together to achieve something extraordinary, something that less than two per cent of the world’s total population has ever achieved: completing a marathon. It’s a humbling, inspiring thing to see, hear and be surrounded by. It’s awesome. Truly, it is.

Today, running is still a massive part of my life. I may have two artificial knees – not the result of a lifetime of racing, I hasten to add – but I go to bed at night and can hardly wait to get up in the morning to go for a run. I still love it just as much as I ever did.

When I retired, so many people said to me, ‘I bet you’ll never run again.’ Truth is, I could never do that. I still class myself as a runner, a competitor. That fire still burns and I truly believe that it’s in every single one of us. You just have to fan the flames every so often.

It doesn’t matter if you’ve never run before. You’re never too old to start. I know that sounds like a cliché but the only reason you hear it so much is because it’s true. I’ve had people come up to me who have sat on the couch most of their lives and, suddenly, they hit fifty or sixty and decide to run a marathon. And, at first, that’s all you need – desire. Sure, you’ve got to train, watch what you eat and be prepared to make some temporary sacrifices but you can’t even get to that point without desire. It’s what separates marathon runners from would-be marathon runners. It is, in simple terms, the difference.

If you’re thinking about running the London Marathon, my advice is simple – stop thinking and start doing. It’s an incredible race, in a beautiful city, well organised, with generally good weather conditions and perhaps the greatest support you will ever experience putting one foot in front of the other. If your motivation is the entitlement to say, ‘I ran a marathon’, there’s no better event.

I hear its name, I see its pictures, I watch its footage and every hair on the back of my neck stands to attention.

It changed my life. It will change yours, too.

CHAPTER TWO

LLOYD SCOTT

Former professional footballer and firefighter Lloyd Scott was given less than a ten per cent chance of survival when he was diagnosed with leukaemia in 1987. Incredibly, he pulled through and, in 1990, ran the London Marathon to prove there is life after the illness. Subsequently, he has become one of the UK’s most prolific charity campaigners, raising more than £5 million for worthy causes through a variety of endurance-based challenges. The most memorable of these? The time he completed the London Marathon in a deep-sea diving suit.

YOU know the guy who ran the London Marathon in a deep-sea diving suit? That was me. And the guy who ran it dressed as Indiana Jones, dragging a large boulder behind him like the famous scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark? Also me. Or the guy who ran it wearing a suit of armour, or as the ‘Iron Giant’, or as ‘Brian the Snail’ from The Magic Roundabout? Me again.

Yeah, it goes without saying that I love a challenge. In addition to my various London Marathon experiences, I have also completed the Marathon des Sables, a 150-mile ultramarathon through the Sahara Desert; undertaken expeditions to both the North and South Poles; run the world’s first-ever underwater marathon in Loch Ness in 2003; walked from Land’s End to John o’Groats; and climbed Mount Kilimanjaro. And that’s just for starters.

Each and every thing I’ve done has been demanding and difficult in its own way, but nothing compared to the very first big challenge I ever faced: beating leukaemia.

I was diagnosed with the condition in November 1987. At the time, I was a firefighter and part-time footballer. I’d played in goal for the likes of Blackpool, Watford and Leyton Orient. Anyway, one evening, I was called out to help tackle a house fire in Dagenham in east London. Two young boys were trapped inside and I went in to rescue them. During that operation, I inhaled toxic smoke and was taken to hospital for what I thought would be some routine tests. One of them was a blood test, the results of which showed that something wasn’t quite right. Further follow-up tests revealed that I was suffering from chronic myeloid leukaemia. It’s scary to think that if I hadn’t inhaled the smoke that night, it may have gone undetected for many more weeks or months and, of course, with any type of cancer, early diagnosis is crucial.

Even so, my initial prognosis wasn’t good. I needed a bone marrow transplant but immediately hit a stumbling block when neither my brother nor my sister proved to be a match for me. They would be a perfect match for one another, ironically, but not me so I needed to find an ‘unrelated’ match, which, at the time, was both very difficult and very rare. My odds of beating the disease at that point were less than ten per cent. I felt like I was staring down both barrels.

I can remember thinking, ‘Jeez, this is it. This is how I’m going to die.’ However, I gave myself a shake and tried as much as possible to focus on the possibility that I could be cured, no matter how unlikely it seemed at the time. Don’t get me wrong, I had my moments. I can remember one time getting in the car in the middle of the night and driving to London to see the Fire Brigade welfare officer – who was an absolute angel – because I found it hard to share my concerns with my family. As much as possible, though, I tried to just carry on as normal. I continued going to work, kept playing football and so on.

Fortunately, a suitable unrelated donor was found for me to have a transplant at some point in the future. The eighteen-month wait that followed was extremely difficult. It was a real battle just to stay positive. It was around that time that I read the story of a woman who had been undergoing treatment for leukaemia and whose family had decided to bring Christmas forward so she could celebrate with them; you know, in the event that she didn’t pull through. As somebody who was going through something similar, I found that quite unnerving, not to mention upsetting.