Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: e-artnow

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

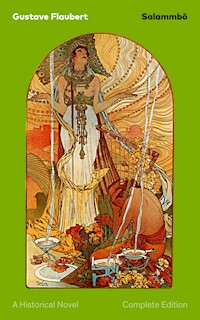

This carefully crafted ebook: "Salammbô - A Historical Novel (Complete Edition)" is formatted for your eReader with a functional and detailed table of contents. Salammbô is a historical novel about a priestess and the daughter of Hamilcar Barca, an aristocratic Carthaginian general. Salammbô is the object of the obsessive lust of Matho, a leader of the mercenaries. With the help of the scheming freed slave, Spendius, Matho steals the sacred veil of Carthage, the Zaïmph, prompting Salammbô to enter the mercenaries' camp in an attempt to steal it back. The Zaïmph is an ornate bejewelled veil draped about the statue of the goddess Tanit in the sanctum sanctorum of her temple: the veil is the city's guardian and touching it will bring death to the perpetrator. The novel is set in Carthage during the 3rd century BC, immediately before and during the Mercenary Revolt which took place shortly after the First Punic War. Flaubert's main source was Book I of Polybius's Histories. It required a great deal of work from the author, who enthusiastically left behind the realism of his masterpiece Madame Bovary for this tale of blood and thunder. The book, which Flaubert researched painstakingly, is largely an exercise in sensuous and violent exoticism. It was another best-seller and sealed his reputation. The Carthaginian costumes described in it even left traces on the fashions of the time. Nevertheless, in spite of its classic status in France, it is not widely known today among English speakers. Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880) was an influential French writer who was perhaps the leading exponent of literary realism of his country. He is known especially for his first published novel, Madame Bovary and for his scrupulous devotion to his style and aesthetics. The celebrated short story writer Maupassant was a protégé of Flaubert.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 531

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Salammbô - A Historical Novel (Complete Edition)

Table of Contents

Chapter I THE FEAST

It was at Megara, a suburb of Carthage, in the gardens of Hamilcar. The soldiers whom he had commanded in Sicily were having a great feast to celebrate the anniversary of the battle of Eryx, and as the master was away, and they were numerous, they ate and drank with perfect freedom.

The captains, who wore bronze cothurni, had placed themselves in the central path, beneath a gold-fringed purple awning, which reached from the wall of the stables to the first terrace of the palace; the common soldiers were scattered beneath the trees, where numerous flat-roofed buildings might be seen, wine-presses, cellars, storehouses, bakeries, and arsenals, with a court for elephants, dens for wild beasts, and a prison for slaves.

Fig-trees surrounded the kitchens; a wood of sycamores stretched away to meet masses of verdure, where the pomegranate shone amid the white tufts of the cotton-plant; vines, grape-laden, grew up into the branches of the pines; a field of roses bloomed beneath the plane-trees; here and there lilies rocked upon the turf; the paths were strewn with black sand mingled with powdered coral, and in the centre the avenue of cypress formed, as it were, a double colonnade of green obelisks from one extremity to the other.

Far in the background stood the palace, built of yellow mottled Numidian marble, broad courses supporting its four terraced stories. With its large, straight, ebony staircase, bearing the prow of a vanquished galley at the corners of every step, its red doors quartered with black crosses, its brass gratings protecting it from scorpions below, and its trellises of gilded rods closing the apertures above, it seemed to the soldiers in its haughty opulence as solemn and impenetrable as the face of Hamilcar.

The Council had appointed his house for the holding of this feast; the convalescents lying in the temple of Eschmoun had set out at daybreak and dragged themselves thither on their crutches. Every minute others were arriving. They poured in ceaselessly by every path like torrents rushing into a lake; through the trees the slaves of the kitchens might be seen running scared and half-naked; the gazelles fled bleating on the lawns; the sun was setting, and the perfume of citron trees rendered the exhalation from the perspiring crowd heavier still.

Men of all nations were there, Ligurians, Lusitanians, Balearians, Negroes, and fugitives from Rome. Beside the heavy Dorian dialect were audible the resonant Celtic syllables rattling like chariots of war, while Ionian terminations conflicted with consonants of the desert as harsh as the jackal’s cry. The Greek might be recognised by his slender figure, the Egyptian by his elevated shoulders, the Cantabrian by his broad calves. There were Carians proudly nodding their helmet plumes, Cappadocian archers displaying large flowers painted on their bodies with the juice of herbs, and a few Lydians in women’s robes, dining in slippers and earrings. Others were ostentatiously daubed with vermilion, and resembled coral statues.

They stretched themselves on the cushions, they ate squatting round large trays, or lying face downwards they drew out the pieces of meat and sated themselves, leaning on their elbows in the peaceful posture of lions tearing their prey. The last comers stood leaning against the trees watching the low tables half hidden beneath the scarlet coverings, and awaiting their turn.

Hamilcar’s kitchens being insufficient, the Council had sent them slaves, ware, and beds, and in the middle of the garden, as on a battlefield when they burn the dead, large bright fires might be seen, at which oxen were roasting. Anise-sprinkled loaves alternated with great cheeses heavier than discuses, crateras filled with wine, and cantharuses filled with water, together with baskets of gold filigree-work containing flowers. Every eye was dilated with the joy of being able at last to gorge at pleasure, and songs were beginning here and there.

First they were served with birds and green sauce in plates of red clay relieved by drawings in black, then with every kind of shellfish that is gathered on the Punic coasts, wheaten porridge, beans and barley, and snails dressed with cumin on dishes of yellow amber.

Afterwards the tables were covered with meats, antelopes with their horns, peacocks with their feathers, whole sheep cooked in sweet wine, haunches of she-camels and buffaloes, hedgehogs with garum, fried grasshoppers, and preserved dormice. Large pieces of fat floated in the midst of saffron in bowls of Tamrapanni wood. Everything was running over with wine, truffles, and asafoetida. Pyramids of fruit were crumbling upon honeycombs, and they had not forgotten a few of those plump little dogs with pink silky hair and fattened on olive lees, — a Carthaginian dish held in abhorrence among other nations. Surprise at the novel fare excited the greed of the stomach. The Gauls with their long hair drawn up on the crown of the head, snatched at the watermelons and lemons, and crunched them up with the rind. The Negroes, who had never seen a lobster, tore their faces with its red prickles. But the shaven Greeks, whiter than marble, threw the leavings of their plates behind them, while the herdsmen from Brutium, in their wolf-skin garments, devoured in silence with their faces in their portions.

Night fell. The velarium, spread over the cypress avenue, was drawn back, and torches were brought.

The apes, sacred to the moon, were terrified on the cedar tops by the wavering lights of the petroleum as it burned in the porphyry vases. They uttered screams which afforded mirth to the soldiers.

Oblong flames trembled in cuirasses of brass. Every kind of scintillation flashed from the gem-incrusted dishes. The crateras with their borders of convex mirrors multiplied and enlarged the images of things; the soldiers thronged around, looking at their reflections with amazement, and grimacing to make themselves laugh. They tossed the ivory stools and golden spatulas to one another across the tables. They gulped down all the Greek wines in their leathern bottles, the Campanian wine enclosed in amphoras, the Cantabrian wines brought in casks, with the wines of the jujube, cinnamomum and lotus. There were pools of these on the ground that made the foot slip. The smoke of the meats ascended into the foliage with the vapour of the breath. Simultaneously were heard the snapping of jaws, the noise of speech, songs, and cups, the crash of Campanian vases shivering into a thousand pieces, or the limpid sound of a large silver dish.

In proportion as their intoxication increased they more and more recalled the injustice of Carthage. The Republic, in fact, exhausted by the war, had allowed all the returning bands to accumulate in the town. Gisco, their general, had however been prudent enough to send them back severally in order to facilitate the liquidation of their pay, and the Council had believed that they would in the end consent to some reduction. But at present ill-will was caused by the inability to pay them. This debt was confused in the minds of the people with the 3200 Euboic talents exacted by Lutatius, and equally with Rome they were regarded as enemies to Carthage. The Mercenaries understood this, and their indignation found vent in threats and outbreaks. At last they demanded permission to assemble to celebrate one of their victories, and the peace party yielded, at the same time revenging themselves on Hamilcar who had so strongly upheld the war. It had been terminated notwithstanding all his efforts, so that, despairing of Carthage, he had entrusted the government of the Mercenaries to Gisco. To appoint his palace for their reception was to draw upon him something of the hatred which was borne to them. Moreover, the expense must be excessive, and he would incur nearly the whole.

Proud of having brought the Republic to submit, the Mercenaries thought that they were at last about to return to their homes with the payment for their blood in the hoods of their cloaks. But as seen through the mists of intoxication, their fatigues seemed to them prodigious and but ill-rewarded. They showed one another their wounds, they told of their combats, their travels and the hunting in their native lands. They imitated the cries and the leaps of wild beasts. Then came unclean wagers; they buried their heads in the amphoras and drank on without interruption, like thirsty dromedaries. A Lusitanian of gigantic stature ran over the tables, carrying a man in each hand at arm’s length, and spitting out fire through his nostrils. Some Lacedaemonians, who had not taken off their cuirasses, were leaping with a heavy step. Some advanced like women, making obscene gestures; others stripped naked to fight amid the cups after the fashion of gladiators, and a company of Greeks danced around a vase whereon nymphs were to be seen, while a Negro tapped with an ox-bone on a brazen buckler.

Suddenly they heard a plaintive song, a song loud and soft, rising and falling in the air like the wing-beating of a wounded bird.

It was the voice of the slaves in the ergastulum. Some soldiers rose at a bound to release them and disappeared.

They returned, driving through the dust amid shouts, twenty men, distinguished by their greater paleness of face. Small black felt caps of conical shape covered their shaven heads; they all wore wooden shoes, and yet made a noise as of old iron like driving chariots.

They reached the avenue of cypress, where they were lost among the crowd of those questioning them. One of them remained apart, standing. Through the rents in his tunic his shoulders could be seen striped with long scars. Drooping his chin, he looked round him with distrust, closing his eyelids somewhat against the dazzling light of the torches, but when he saw that none of the armed men were unfriendly to him, a great sigh escaped from his breast; he stammered, he sneered through the bright tears that bathed his face. At last he seized a brimming cantharus by its rings, raised it straight up into the air with his outstretched arms, from which his chains hung down, and then looking to heaven, and still holding the cup he said:

“Hail first to thee, Baal-Eschmoun, the deliverer, whom the people of my country call Aesculapius! and to you, genii of the fountains, light, and woods! and to you, ye gods hidden beneath the mountains and in the caverns of the earth! and to you, strong men in shining armour who have set me free!”

Then he let fall the cup and related his history. He was called Spendius. The Carthaginians had taken him in the battle of Aeginusae, and he thanked the Mercenaries once more in Greek, Ligurian and Punic; he kissed their hands; finally, he congratulated them on the banquet, while expressing his surprise at not perceiving the cups of the Sacred Legion. These cups, which bore an emerald vine on each of their six golden faces, belonged to a corps composed exclusively of young patricians of the tallest stature. They were a privilege, almost a sacerdotal distinction, and accordingly nothing among the treasures of the Republic was more coveted by the Mercenaries. They detested the Legion on this account, and some of them had been known to risk their lives for the inconceivable pleasure of drinking out of these cups.

Accordingly they commanded that the cups should be brought. They were in the keeping of the Syssitia, companies of traders, who had a common table. The slaves returned. At that hour all the members of the Syssitia were asleep.

“Let them be awakened!” responded the Mercenaries.

After a second excursion it was explained to them that the cups were shut up in a temple.

“Let it be opened!” they replied.

And when the slaves confessed with trembling that they were in the possession of Gisco, the general, they cried out:

“Let him bring them!”

Gisco soon appeared at the far end of the garden with an escort of the Sacred Legion. His full, black cloak, which was fastened on his head to a golden mitre starred with precious stones, and which hung all about him down to his horse’s hoofs, blended in the distance with the colour of the night. His white beard, the radiancy of his headdress, and his triple necklace of broad blue plates beating against his breast, were alone visible.

When he entered, the soldiers greeted him with loud shouts, all crying:

“The cups! The cups!”

He began by declaring that if reference were had to their courage, they were worthy of them.

The crowd applauded and howled with joy.

HE knew it, he who had commanded them over yonder, and had returned with the last cohort in the last galley!

“True! True!” said they.

Nevertheless, Gisco continued, the Republic had respected their national divisions, their customs, and their modes of worship; in Carthage they were free! As to the cups of the Sacred Legion, they were private property. Suddenly a Gaul, who was close to Spendius, sprang over the tables and ran straight up to Gisco, gesticulating and threatening him with two naked swords.

Without interrupting his speech, the General struck him on the head with his heavy ivory staff, and the Barbarian fell. The Gauls howled, and their frenzy, which was spreading to the others, would soon have swept away the legionaries. Gisco shrugged his shoulders as he saw them growing pale. He thought that his courage would be useless against these exasperated brute beasts. It would be better to revenge himself upon them by some artifice later; accordingly, he signed to his soldiers and slowly withdrew. Then, turning in the gateway towards the Mercenaries, he cried to them that they would repent of it.

The feast recommenced. But Gisco might return, and by surrounding the suburb, which was beside the last ramparts, might crush them against the walls. Then they felt themselves alone in spite of their crowd, and the great town sleeping beneath them in the shade suddenly made them afraid, with its piles of staircases, its lofty black houses, and its vague gods fiercer even than its people. In the distance a few ships’-lanterns were gliding across the harbour, and there were lights in the temple of Khamon. They thought of Hamilcar. Where was he? Why had he forsaken them when peace was concluded? His differences with the Council were doubtless but a pretence in order to destroy them. Their unsatisfied hate recoiled upon him, and they cursed him, exasperating one another with their own anger. At this juncture they collected together beneath the plane-trees to see a slave who, with eyeballs fixed, neck contorted, and lips covered with foam, was rolling on the ground, and beating the soil with his limbs. Some one cried out that he was poisoned. All then believed themselves poisoned. They fell upon the slaves, a terrible clamour was raised, and a vertigo of destruction came like a whirlwind upon the drunken army. They struck about them at random, they smashed, they slew; some hurled torches into the foliage; others, leaning over the lions’ balustrade, massacred the animals with arrows; the most daring ran to the elephants, desiring to cut down their trunks and eat ivory.

Some Balearic slingers, however, who had gone round the corner of the palace, in order to pillage more conveniently, were checked by a lofty barrier, made of Indian cane. They cut the lock-straps with their daggers, and then found themselves beneath the front that faced Carthage, in another garden full of trimmed vegetation. Lines of white flowers all following one another in regular succession formed long parabolas like star-rockets on the azure-coloured earth. The gloomy bushes exhaled warm and honied odours. There were trunks of trees smeared with cinnabar, which resembled columns covered with blood. In the centre were twelve pedestals, each supporting a great glass ball, and these hollow globes were indistinctly filled with reddish lights, like enormous and still palpitating eyeballs. The soldiers lighted themselves with torches as they stumbled on the slope of the deeply laboured soil.

But they perceived a little lake divided into several basins by walls of blue stones. So limpid was the wave that the flames of the torches quivered in it at the very bottom, on a bed of white pebbles and golden dust. It began to bubble, luminous spangles glided past, and great fish with gems about their mouths, appeared near the surface.

With much laughter the soldiers slipped their fingers into the gills and brought them to the tables. They were the fish of the Barca family, and were all descended from those primordial lotes which had hatched the mystic egg wherein the goddess was concealed. The idea of committing a sacrilege revived the greediness of the Mercenaries; they speedily placed fire beneath some brazen vases, and amused themselves by watching the beautiful fish struggling in the boiling water.

The surge of soldiers pressed on. They were no longer afraid. They commenced to drink again. Their ragged tunics were wet with the perfumes that flowed in large drops from their foreheads, and resting both fists on the tables, which seemed to them to be rocking like ships, they rolled their great drunken eyes around to devour by sight what they could not take. Others walked amid the dishes on the purple table covers, breaking ivory stools, and phials of Tyrian glass to pieces with their feet. Songs mingled with the death-rattle of the slaves expiring amid the broken cups. They demanded wine, meat, gold. They cried out for women. They raved in a hundred languages. Some thought that they were at the vapour baths on account of the steam which floated around them, or else, catching sight of the foliage, imagined that they were at the chase, and rushed upon their companions as upon wild beasts. The conflagration spread to all the trees, one after another, and the lofty mosses of verdure, emitting long white spirals, looked like volcanoes beginning to smoke. The clamour redoubled; the wounded lions roared in the shade.

In an instant the highest terrace of the palace was illuminated, the central door opened, and a woman, Hamilcar’s daughter herself, clothed in black garments, appeared on the threshold. She descended the first staircase, which ran obliquely along the first story, then the second, and the third, and stopped on the last terrace at the head of the galley staircase. Motionless and with head bent, she gazed upon the soldiers.

Behind her, on each side, were two long shadows of pale men, clad in white, red-fringed robes, which fell straight to their feet. They had no beard, no hair, no eyebrows. In their hands, which sparkled with rings, they carried enormous lyres, and with shrill voice they sang a hymn to the divinity of Carthage. They were the eunuch priests of the temple of Tanith, who were often summoned by Salammbo to her house.

At last she descended the galley staircase. The priests followed her. She advanced into the avenue of cypress, and walked slowly through the tables of the captains, who drew back somewhat as they watched her pass.

Her hair, which was powdered with violet sand, and combined into the form of a tower, after the fashion of the Chanaanite maidens, added to her height. Tresses of pearls were fastened to her temples, and fell to the corners of her mouth, which was as rosy as a half-open pomegranate. On her breast was a collection of luminous stones, their variegation imitating the scales of the murena. Her arms were adorned with diamonds, and issued naked from her sleeveless tunic, which was starred with red flowers on a perfectly black ground. Between her ankles she wore a golden chainlet to regulate her steps, and her large dark purple mantle, cut of an unknown material, trailed behind her, making, as it were, at each step, a broad wave which followed her.

The priests played nearly stifled chords on their lyres from time to time, and in the intervals of the music might be heard the tinkling of the little golden chain, and the regular patter of her papyrus sandals.

No one as yet was acquainted with her. It was only known that she led a retired life, engaged in pious practices. Some soldiers had seen her in the night on the summit of her palace kneeling before the stars amid the eddyings from kindled perfuming-pans. It was the moon that had made her so pale, and there was something from the gods that enveloped her like a subtle vapour. Her eyes seemed to gaze far beyond terrestrial space. She bent her head as she walked, and in her right hand she carried a little ebony lyre.

They heard her murmur:

“Dead! All dead! No more will you come obedient to my voice as when, seated on the edge of the lake, I used to through seeds of the watermelon into your mouths! The mystery of Tanith ranged in the depths of your eyes that were more limpid than the globules of rivers.” And she called them by their names, which were those of the months — “Siv! Sivan! Tammouz, Eloul, Tischri, Schebar! Ah! have pity on me, goddess!”

The soldiers thronged about her without understanding what she said. They wondered at her attire, but she turned a long frightened look upon them all, then sinking her head beneath her shoulders, and waving her arms, she repeated several times:

“What have you done? what have you done?

“Yet you had bread, and meats and oil, and all the malobathrum of the granaries for your enjoyment! I had brought oxen from Hecatompylos; I had sent hunters into the desert!” Her voice swelled; her cheeks purpled. She added, “Where, pray, are you now? In a conquered town, or in the palace of a master? And what master? Hamilcar the Suffet, my father, the servant of the Baals! It was he who withheld from Lutatius those arms of yours, red now with the blood of his slaves! Know you of any in your own lands more skilled in the conduct of battles? Look! our palace steps are encumbered with our victories! Ah! desist not! burn it! I will carry away with me the genius of my house, my black serpent slumbering up yonder on lotus leaves! I will whistle and he will follow me, and if I embark in a galley he will speed in the wake of my ship over the foam of the waves.”

Her delicate nostrils were quivering. She crushed her nails against the gems on her bosom. Her eyes drooped, and she resumed:

“Ah! poor Carthage! lamentable city! No longer hast thou for thy protection the strong men of former days who went beyond the oceans to build temples on their shores. All the lands laboured about thee, and the sea-plains, ploughed by thine oars, rocked with thy harvests.” Then she began to sing the adventures of Melkarth, the god of the Sidonians, and the father of her family.

She told of the ascent of the mountains of Ersiphonia, the journey to Tartessus, and the war against Masisabal to avenge the queen of the serpents:

“He pursued the female monster, whose tail undulated over the dead leaves like a silver brook, into the forest, and came to a plain where women with dragon-croups were round a great fire, standing erect on the points of their tails. The blood-coloured moon was shining within a pale circle, and their scarlet tongues, cloven like the harpoons of fishermen, reached curling forth to the very edge of the flame.”

Then Salammbo, without pausing, related how Melkarth, after vanquishing Masisabal, placed her severed head on the prow of his ship. “At each throb of the waves it sank beneath the foam, but the sun embalmed it; it became harder than gold; nevertheless the eyes ceased not to weep, and the tears fell into the water continually.”

She sang all this in an old Chanaanite idiom, which the Barbarians did not understand. They asked one another what she could be saying to them with those frightful gestures which accompanied her speech, and mounted round about her on the tables, beds, and sycamore boughs, they strove with open mouths and craned necks to grasp the vague stories hovering before their imaginations, through the dimness of the theogonies, like phantoms wrapped in cloud.

Only the beardless priests understood Salammbo; their wrinkled hands, which hung over the strings of their lyres, quivered, and from time to time they would draw forth a mournful chord; for, feebler than old women, they trembled at once with mystic emotion, and with the fear inspired by men. The Barbarians heeded them not, but listened continually to the maiden’s song.

None gazed at her like a young Numidian chief, who was placed at the captains’ tables among soldiers of his own nation. His girdle so bristled with darts that it formed a swelling in his ample cloak, which was fastened on his temples with a leather lace. The cloth parted asunder as it fell upon his shoulders, and enveloped his countenance in shadow, so that only the fires of his two fixed eyes could be seen. It was by chance that he was at the feast, his father having domiciled him with the Barca family, according to the custom by which kings used to send their children into the households of the great in order to pave the way for alliances; but Narr’ Havas had lodged there fox six months without having hitherto seen Salammbo, and now, seated on his heels, with his head brushing the handles of his javelins, he was watching her with dilated nostrils, like a leopard crouching among the bamboos.

On the other side of the tables was a Libyan of colossal stature, and with short black curly hair. He had retained only his military jacket, the brass plates of which were tearing the purple of the couch. A necklace of silver moons was tangled in his hairy breast. His face was stained with splashes of blood; he was leaning on his left elbow with a smile on his large, open mouth.

Salammbo had abandoned the sacred rhythm. With a woman’s subtlety she was simultaneously employing all the dialects of the Barbarians in order to appease their anger. To the Greeks she spoke Greek; then she turned to the Ligurians, the Campanians, the Negroes, and listening to her each one found again in her voice the sweetness of his native land. She now, carried away by the memories of Carthage, sang of the ancient battles against Rome; they applauded. She kindled at the gleaming of the naked swords, and cried aloud with outstretched arms. Her lyre fell, she was silent; and, pressing both hands upon her heart, she remained for some minutes with closed eyelids enjoying the agitation of all these men.

Matho, the Libyan, leaned over towards her. Involuntarily she approached him, and impelled by grateful pride, poured him a long stream of wine into a golden cup in order to conciliate the army.

“Drink!” she said.

He took the cup, and was carrying it to his lips when a Gaul, the same that had been hurt by Gisco, struck him on the shoulder, while in a jovial manner he gave utterance to pleasantries in his native tongue. Spendius was not far off, and he volunteered to interpret them.

“Speak!” said Matho.

“The gods protect you; you are going to become rich. When will the nuptials be?”

“What nuptials?”

“Yours! for with us,” said the Gaul, “when a woman gives drink to a soldier, it means that she offers him her couch.”

He had not finished when Narr’ Havas, with a bound, drew a javelin from his girdle, and, leaning his right foot upon the edge of the table, hurled it against Matho.

The javelin whistled among the cups, and piercing the Lybian’s arm, pinned it so firmly to the cloth, that the shaft quivered in the air.

Matho quickly plucked it out; but he was weaponless and naked; at last he lifted the overladen table with both arms, and flung it against Narr’ Havas into the very centre of the crowd that rushed between them. The soldiers and Numidians pressed together so closely that they were unable to draw their swords. Matho advanced dealing great blows with his head. When he raised it, Narr’ Havas had disappeared. He sought for him with his eyes. Salammbo also was gone.

Then directing his looks to the palace he perceived the red door with the black cross closing far above, and he darted away.

They saw him run between the prows of the galleys, and then reappear along the three staircases until he reached the red door against which he dashed his whole body. Panting, he leaned against the wall to keep himself from falling.

But a man had followed him, and through the darkness, for the lights of the feast were hidden by the corner of the palace, he recognised Spendius.

“Begone!” said he.

The slave without replying began to tear his tunic with his teeth; then kneeling beside Matho he tenderly took his arm, and felt it in the shadow to discover the wound.

By a ray of the moon which was then gliding between the clouds, Spendius perceived a gaping wound in the middle of the arm. He rolled the piece of stuff about it, but the other said irritably, “Leave me! leave me!”

“Oh no!” replied the slave. “You released me from the ergastulum. I am yours! you are my master! command me!”

Matho walked round the terrace brushing against the walls. He strained his ears at every step, glancing down into the silent apartments through the spaces between the gilded reeds. At last he stopped with a look of despair.

“Listen!” said the slave to him. “Oh! do not despise me for my feebleness! I have lived in the palace. I can wind like a viper through the walls. Come! in the Ancestor’s Chamber there is an ingot of gold beneath every flagstone; an underground path leads to their tombs.”

“Well! what matters it?” said Matho.

Spendius was silent.

They were on the terrace. A huge mass of shadow stretched before them, appearing as if it contained vague accumulations, like the gigantic billows of a black and petrified ocean.

But a luminous bar rose towards the East; far below, on the left, the canals of Megara were beginning to stripe the verdure of the gardens with their windings of white. The conical roofs of the heptagonal temples, the staircases, terraces, and ramparts were being carved by degrees upon the paleness of the dawn; and a girdle of white foam rocked around the Carthaginian peninsula, while the emerald sea appeared as if it were curdled in the freshness of the morning. Then as the rosy sky grew larger, the lofty houses, bending over the sloping soil, reared and massed themselves like a herd of black goats coming down from the mountains. The deserted streets lengthened; the palm-trees that topped the walls here and there were motionless; the brimming cisterns seemed like silver bucklers lost in the courts; the beacon on the promontory of Hermaeum was beginning to grow pale. The horses of Eschmoun, on the very summit of the Acropolis in the cypress wood, feeling that the light was coming, placed their hoofs on the marble parapet, and neighed towards the sun.

It appeared, and Spendius raised his arms with a cry.

Everything stirred in a diffusion of red, for the god, as if he were rending himself, now poured full-rayed upon Carthage the golden rain of his veins. The beaks of the galleys sparkled, the roof of Khamon appeared to be all in flames, while far within the temples, whose doors were opening, glimmerings of light could be seen. Large chariots, arriving from the country, rolled their wheels over the flagstones in the streets. Dromedaries, baggage-laden, came down the ramps. Money-changers raised the penthouses of their shops at the cross ways, storks took to flight, white sails fluttered. In the wood of Tanith might be heard the tabourines of the sacred courtesans, and the furnaces for baking the clay coffins were beginning to smoke on the Mappalian point.

Spendius leaned over the terrace; his teeth chattered and he repeated:

“Ah! yes — yes — master! I understand why you scorned the pillage of the house just now.”

Matho was as if he had just been awaked by the hissing of his voice, and did not seem to understand. Spendius resumed:

“Ah! what riches! and the men who possess them have not even the steel to defend them!”

Then, pointing with his right arm outstretched to some of the populace who were crawling on the sand outside the mole to look for gold dust:

“See!” he said to him, “the Republic is like these wretches: bending on the brink of the ocean, she buries her greedy arms in every shore, and the noise of the billows so fills her ear that she cannot hear behind her the tread of a master’s heel!”

He drew Matho to quite the other end of the terrace, and showed him the garden, wherein the soldiers’ swords, hanging on the trees, were like mirrors in the sun.

“But here there are strong men whose hatred is roused! and nothing binds them to Carthage, neither families, oaths nor gods!”

Matho remained leaning against the wall; Spendius came close, and continued in a low voice:

“Do you understand me, soldier? We should walk purple-clad like satraps. We should bathe in perfumes; and I should in turn have slaves! Are you not weary of sleeping on hard ground, of drinking the vinegar of the camps, and of continually hearing the trumpet? But you will rest later, will you not? When they pull off your cuirass to cast your corpse to the vultures! or perhaps blind, lame, and weak you will go, leaning on a stick, from door to door to tell of your youth to pickle-sellers and little children. Remember all the injustice of your chiefs, the campings in the snow, the marchings in the sun, the tyrannies of discipline, and the everlasting menace of the cross! And after all this misery they have given you a necklace of honour, as they hang a girdle of bells round the breast of an ass to deafen it on its journey, and prevent it from feeling fatigue. A man like you, braver than Pyrrhus! If only you had wished it! Ah! how happy will you be in large cool halls, with the sound of lyres, lying on flowers, with women and buffoons! Do not tell me that the enterprise is impossible. Have not the Mercenaries already possessed Rhegium and other fortified places in Italy? Who is to prevent you? Hamilcar is away; the people execrate the rich; Gisco can do nothing with the cowards who surround him. Command them! Carthage is ours; let us fall upon it!”

“No!” said Matho, “the curse of Moloch weighs upon me. I felt it in her eyes, and just now I saw a black ram retreating in a temple.” Looking around him he added: “But where is she?”

Then Spendius understood that a great disquiet possessed him, and did not venture to speak again.

The trees behind them were still smoking; half-burned carcases of apes dropped from their blackened boughs from time to time into the midst of the dishes. Drunken soldiers snored open-mouthed by the side of the corpses, and those who were not asleep lowered their heads dazzled by the light of day. The trampled soil was hidden beneath splashes of red. The elephants poised their bleeding trunks between the stakes of their pens. In the open granaries might be seen sacks of spilled wheat, below the gate was a thick line of chariots which had been heaped up by the Barbarians, and the peacocks perched in the cedars were spreading their tails and beginning to utter their cry.

Matho’s immobility, however, astonished Spendius; he was even paler than he had recently been, and he was following something on the horizon with fixed eyeballs, and with both fists resting on the edge of the terrace. Spendius crouched down, and so at last discovered at what he was gazing. In the distance a golden speck was turning in the dust on the road to Utica; it was the nave of a chariot drawn by two mules; a slave was running at the end of the pole, and holding them by the bridle. Two women were seated in the chariot. The manes of the animals were puffed between the ears after the Persian fashion, beneath a network of blue pearls. Spendius recognised them, and restrained a cry.

A large veil floated behind in the wind.

Chapter II AT SICCA

Two days afterwards the Mercenaries left Carthage.

They had each received a piece of gold on the condition that they should go into camp at Sicca, and they had been told with all sorts of caresses:

“You are the saviours of Carthage! But you would starve it if you remained there; it would become insolvent. Withdraw! The Republic will be grateful to you later for all this condescension. We are going to levy taxes immediately; your pay shall be in full, and galleys shall be equipped to take you back to your native lands.”

They did not know how to reply to all this talk. These men, accustomed as they were to war, were wearied by residence in a town; there was difficulty in convincing them, and the people mounted the walls to see them go away.

They defiled through the street of Khamon, and the Cirta gate, pellmell, archers with hoplites, captains with soldiers, Lusitanians with Greeks. They marched with a bold step, rattling their heavy cothurni on the paving stones. Their armour was dented by the catapult, and their faces blackened by the sunburn of battles. Hoarse cries issued from their thick bears, their tattered coats of mail flapped upon the pommels of their swords, and through the holes in the brass might be seen their naked limbs, as frightful as engines of war. Sarissae, axes, spears, felt caps and bronze helmets, all swung together with a single motion. They filled the street thickly enough to have made the walls crack, and the long mass of armed soldiers overflowed between the lofty bitumen-smeared houses six storys high. Behind their gratings of iron or reed the women, with veiled heads, silently watched the Barbarians pass.

The terraces, fortifications, and walls were hidden beneath the crowd of Carthaginians, who were dressed in garments of black. The sailors’ tunics showed like drops of blood among the dark multitude, and nearly naked children, whose skin shone beneath their copper bracelets, gesticulated in the foliage of the columns, or amid the branches of a palm tree. Some of the Ancients were posted on the platform of the towers, and people did not know why a personage with a long beard stood thus in a dreamy attitude here and there. He appeared in the distance against the background of the sky, vague as a phantom and motionless as stone.

All, however, were oppressed with the same anxiety; it was feared that the Barbarians, seeing themselves so strong, might take a fancy to stay. But they were leaving with so much good faith that the Carthaginians grew bold and mingled with the soldiers. They overwhelmed them with protestations and embraces. Some with exaggerated politeness and audacious hypocrisy even sought to induce them not to leave the city. They threw perfumes, flowers, and pieces of silver to them. They gave them amulets to avert sickness; but they had spit upon them three times to attract death, or had enclosed jackal’s hair within them to put cowardice into their hearts. Aloud, they invoked Melkarth’s favour, and in a whisper, his curse.

Then came the mob of baggage, beasts of burden, and stragglers. The sick groaned on the backs of dromedaries, while others limped along leaning on broken pikes. The drunkards carried leathern bottles, and the greedy quarters of meat, cakes, fruits, butter wrapped in fig leaves, and snow in linen bags. Some were to be seen with parasols in their hands, and parrots on their shoulders. They had mastiffs, gazelles, and panthers following behind them. Women of Libyan race, mounted on asses, inveighed against the Negresses who had forsaken the lupanaria of Malqua for the soldiers; many of them were suckling children suspended on their bosoms by leathern thongs. The mules were goaded out at the point of the sword, their backs bending beneath the load of tents, while there were numbers of serving-men and water-carriers, emaciated, jaundiced with fever, and filthy with vermin, the scum of the Carthaginian populace, who had attached themselves to the Barbarians.

When they had passed, the gates were shut behind them, but the people did not descend from the walls. The army soon spread over the breadth of the isthmus.

It parted into unequal masses. Then the lances appeared like tall blades of grass, and finally all was lost in a train of dust; those of the soldiers who looked back towards Carthage could now only see its long walls with their vacant battlements cut out against the edge of the sky.

Then the Barbarians heard a great shout. They thought that some from among them (for they did not know their own number) had remained in the town, and were amusing themselves by pillaging a temple. They laughed a great deal at the idea of this, and then continued their journey.

They were rejoiced to find themselves, as in former days, marching all together in the open country, and some of the Greeks sang the old song of the Mamertines:

“With my lance and sword I plough and reap; I am master of the house! The disarmed man falls at my feet and calls me Lord and Great King.”

They shouted, they leaped, the merriest began to tell stories; the time of their miseries was past. As they arrived at Tunis, some of them remarked that a troop of Balearic slingers was missing. They were doubtless not far off; and no further heed was paid to them.

Some went to lodge in the houses, others camped at the foot of the walls, and the townspeople came out to chat with the soldiers.

During the whole night fires were seen burning on the horizon in the direction of Carthage; the light stretched like giant torches across the motionless lake. No one in the army could tell what festival was being celebrated.

On the following day the Barbarian’s passed through a region that was covered with cultivation. The domains of the patricians succeeded one another along the border of the route; channels of water flowed through woods of palm; there were long, green lines of olive-trees; rose-coloured vapours floated in the gorges of the hills, while blue mountains reared themselves behind. A warm wind was blowing. Chameleons were crawling on the broad leaves of the cactus.

The Barbarians slackened their speed.

They marched on in isolated detachments, or lagged behind one another at long intervals. They ate grapes along the margin of the vines. They lay on the grass and gazed with stupefaction upon the large, artificially twisted horns of the oxen, the sheep clothed with skins to protect their wool, the furrows crossing one another so as to form lozenges, and the ploughshares like ships’ anchors, with the pomegranate trees that were watered with silphium. Such wealth of the soil and such inventions of wisdom dazzled them.

In the evening they stretched themselves on the tents without unfolding them; and thought with regret of Hamilcar’s feast, as they fell asleep with their faces towards the stars.

In the middle of the following day they halted on the bank of a river, amid clumps of rose-bays. Then they quickly threw aside lances, bucklers and belts. They bathed with shouts, and drew water in their helmets, while others drank lying flat on their stomachs, and all in the midst of the beasts of burden whose baggage was slipping from them.

Spendius, who was seated on a dromedary stolen in Hamilcar’s parks, perceived Matho at a distance, with his arm hanging against his breast, his head bare, and his face bent down, giving his mule drink, and watching the water flow. Spendius immediately ran through the crowd calling him, “Master! master!”

Matho gave him but scant thanks for his blessings, but Spendius paid no heed to this, and began to march behind him, from time to time turning restless glances in the direction of Carthage.

He was the son of a Greek rhetor and a Campanian prostitute. He had at first grown rich by dealing in women; then, ruined by a shipwreck, he had made war against the Romans with the herdsmen of Samnium. He had been taken and had escaped; he had been retaken, and had worked in the quarries, panted in the vapour-baths, shrieked under torture, passed through the hands of many masters, and experienced every frenzy. At last, one day, in despair, he had flung himself into the sea from the top of a trireme where he was working at the oar. Some of Hamilcar’s sailors had picked him up when at the point of death, and had brought him to the ergastulum of Megara, at Carthage. But, as fugitives were to be given back to the Romans, he had taken advantage of the confusion to fly with the soldiers.

During the whole of the march he remained near Matho; he brought him food, assisted him to dismount, and spread a carpet in the evening beneath his head. Matho at last was touched by these attentions, and by degrees unlocked his lips.

He had been born in the gulf of Syrtis. His father had taken him on a pilgrimage to the temple of Ammon. Then he had hunted elephants in the forests of the Garamantes. Afterwards he had entered the service of Carthage. He had been appointed tetrarch at the capture of Drepanum. The Republic owed him four horses, twenty-three medimni of wheat, and a winter’s pay. He feared the gods, and wished to die in his native land.

Spendius spoke to him of his travels, and of the peoples and temples that he had visited. He knew many things: he could make sandals, boar-spears and nets; he could tame wild beasts and could cook fish.

Sometimes he would interrupt himself, and utter a hoarse cry from the depths of his throat; Matho’s mule would quicken his pace, and others would hasten after them, and then Spendius would begin again though still torn with agony. This subsided at last on the evening of the fourth day.

They were marching side by side to the right of the army on the side of a hill; below them stretched the plain lost in the vapours of the night. The lines of soldiers also were defiling below, making undulations in the shade. From time to time these passed over eminences lit up by the moon; then stars would tremble on the points of the pikes, the helmets would glimmer for an instant, all would disappear, and others would come on continually. Startled flocks bleated in the distance, and a something of infinite sweetness seemed to sink upon the earth.

Spendius, with his head thrown back and his eyes half-closed, inhaled the freshness of the wind with great sighs; he spread out his arms, moving his fingers that he might the better feel the cares that streamed over his body. Hopes of vengeance came back to him and transported him. He pressed his hand upon his mouth to check his sobs, and half-swooning with intoxication, let go the halter of his dromedary, which was proceeding with long, regular steps. Matho had relapsed into his former melancholy; his legs hung down to the ground, and the grass made a continuous rustling as it beat against his cothurni.

The journey, however, spread itself out without ever coming to an end. At the extremity of a plain they would always reach a round-shaped plateau; then they would descend again into a valley, and the mountains which seemed to block up the horizon would, in proportion as they were approached, glide as it were from their positions. From time to time a river would appear amid the verdure of tamarisks to lose itself at the turning of the hills. Sometimes a huge rock would tower aloft like the prow of a vessel or the pedestal of some vanished colossus.

At regular intervals they met with little quadrangular temples, which served as stations for the pilgrims who repaired to Sicca. They were closed like tombs. The Libyans struck great blows upon the doors to have them opened. But no one inside responded.

Then the cultivation became more rare. They suddenly entered upon belts of sand bristling with thorny thickets. Flocks of sheep were browsing among the stones; a woman with a blue fleece about her waist was watching them. She fled screaming when she saw the soldiers’ pikes among the rocks.

They were marching through a kind of large passage bordered by two chains of reddish coloured hillocks, when their nostrils were greeted with a nauseous odour, and they thought that they could see something extraordinary on the top of a carob tree: a lion’s head reared itself above the leaves.

They ran thither. It was a lion with his four limbs fastened to a cross like a criminal. His huge muzzle fell upon his breast, and his two forepaws, half-hidden beneath the abundance of his mane, were spread out wide like the wings of a bird. His ribs stood severally out beneath his distended skin; his hind legs, which were nailed against each other, were raised somewhat, and the black blood, flowing through his hair, had collected in stalactites at the end of his tail, which hung down perfectly straight along the cross. The soldiers made merry around; they called him consul, and Roman citizen, and threw pebbles into his eyes to drive away the gnats.

But a hundred paces further on they saw two more, and then there suddenly appeared a long file of crosses bearing lions. Some had been so long dead that nothing was left against the wood but the remains of their skeletons; others which were half eaten away had their jaws twisted into horrible grimaces; there were some enormous ones; the shafts of the crosses bent beneath them, and they swayed in the wind, while bands of crows wheeled ceaselessly in the air above their heads. It was thus that the Carthaginian peasants avenged themselves when they captured a wild beast; they hoped to terrify the others by such an example. The Barbarians ceased their laughter, and were long lost in amazement. “What people is this,” they thought, “that amuses itself by crucifying lions!”

They were, besides, especially the men of the North, vaguely uneasy, troubled, and already sick. They tore their hands with the darts of the aloes; great mosquitoes buzzed in their ears, and dysentry was breaking out in the army. They were weary at not yet seeing Sicca. They were afraid of losing themselves and of reaching the desert, the country of sands and terrors. Many even were unwilling to advance further. Others started back to Carthage.

At last on the seventh day, after following the base of a mountain for a long time, they turned abruptly to the right, and there then appeared a line of walls resting on white rocks and blending with them. Suddenly the entire city rose; blue, yellow, and white veils moved on the walls in the redness of the evening. These were the priestesses of Tanith, who had hastened hither to receive the men. They stood ranged along the rampart, striking tabourines, playing lyres, and shaking crotala, while the rays of the sun, setting behind them in the mountains of Numidia, shot between the strings of their lyres over which their naked arms were stretched. At intervals their instruments would become suddenly still, and a cry would break forth strident, precipitate, frenzied, continuous, a sort of barking which they made by striking both corners of the mouth with the tongue. Others, more motionless than the Sphynx, rested on their elbows with their chins on their hands, and darted their great black eyes upon the army as it ascended.

Although Sicca was a sacred town it could not hold such a multitude; the temple alone, with its appurtenances, occupied half of it. Accordingly the Barbarians established themselves at their ease on the plain; those who were disciplined in regular troops, and the rest according to nationality or their own fancy.

The Greeks ranged their tents of skin in parallel lines; the Iberians placed their canvas pavilions in a circle; the Gauls made themselves huts of planks; the Libyans cabins of dry stones, while the Negroes with their nails hollowed out trenches in the sand to sleep in. Many, not knowing where to go, wandered about among the baggage, and at nightfall lay down in their ragged mantles on the ground.

The plain, which was wholly bounded by mountains, expanded around them. Here and there a palm tree leaned over a sand hill, and pines and oaks flecked the sides of the precipices: sometimes the rain of a storm would hang from the sky like a long scarf, while the country everywhere was still covered with azure and serenity; then a warm wind would drive before it tornadoes of dust, and a stream would descend in cascades from the heights of Sicca, where, with its roofing of gold on its columns of brass, rose the temple of the Carthaginian Venus, the mistress of the land. She seemed to fill it with her soul. In such convulsions of the soil, such alternations of temperature, and such plays of light would she manifest the extravagance of her might with the beauty of her eternal smile. The mountains at their summits were crescent-shaped; others were like women’s bosoms presenting their swelling breasts, and the Barbarians felt a heaviness that was full of delight weighing down their fatigues.

Spendius had bought a slave with the money brought him by his dromedary. The whole day long he lay asleep stretched before Matho’s tent. Often he would awake, thinking in his dreams that he heard the whistling of the thongs; with a smile he would pass his hands over the scars on his legs at the place where the fetters had long been worn, and then he would fall asleep again.

Matho accepted his companionship, and when he went out Spendius would escort him like a lictor with a long sword on his thigh; or perhaps Matho would rest his arm carelessly on the other’s shoulder, for Spendius was small.

One evening when they were passing together through the streets in the camp they perceived some men covered with white cloaks; among them was Narr’ Havas, the prince of the Numidians. Matho started.

“Your sword!” he cried; “I will kill him!”

“Not yet!” said Spendius, restraining him. Narr’ Havas was already advancing towards him.

He kissed both thumbs in token of alliance, showing nothing of the anger which he had experienced at the drunkenness of the feast; then he spoke at length against Carthage, but did not say what brought him among the Barbarians.

“Was it to betray them, or else the Republic?” Spendius asked himself; and as he expected to profit by every disorder, he felt grateful to Narr’ Havas for the future perfidies of which he suspected him.

The chief of the Numidians remained amongst the Mercenaries. He appeared desirous of attaching Matho to himself. He sent him fat goats, gold dust, and ostrich feathers. The Libyan, who was amazed at such caresses, was in doubt whether to respond to them or to become exasperated at them. But Spendius pacified him, and Matho allowed himself to be ruled by the slave, remaining ever irresolute and in an unconquerable torpor, like those who have once taken a draught of which they are to die.

One morning when all three went out lion-hunting, Narr’ Havas concealed a dagger in his cloak. Spendius kept continually behind him, and when they returned the dagger had not been drawn.

Another time Narr’ Havas took them a long way off, as far as the boundaries of his kingdom. They came to a narrow gorge, and Narr’ Havas smiled as he declared that he had forgotten the way. Spendius found it again.

But most frequently Matho would go off at sunrise, as melancholy as an augur, to wander about the country. He would stretch himself on the sand, and remain there motionless until the evening.

He consulted all the soothsayers in the army one after the other, — those who watch the trail of serpents, those who read the stars, and those who breathe upon the ashes of the dead. He swallowed galbanum, seseli, and viper’s venom which freezes the heart; Negro women, singing barbarous words in the moonlight, pricked the skin of his forehead with golden stylets; he loaded himself with necklaces and charms; he invoked in turn Baal-Khamon, Moloch, the seven Kabiri, Tanith, and the Venus of the Greeks. He engraved a name upon a copper plate, and buried it in the sand at the threshold of his tent. Spendius used to hear him groaning and talking to himself.

One night he went in.

Matho, as naked as a corpse, was lying on a lion’s skin flat on his stomach, with his face in both his hands; a hanging lamp lit up his armour, which was hooked on to the tent-pole above his head.

“You are suffering?” said the slave to him. “What is the matter with you? Answer me?” And he shook him by the shoulder calling him several times, “Master! master!”

At last Matho lifted large troubled eyes towards him.

“Listen!” he said in a low voice, and with a finger on his lips. “It is the wrath of the Gods! Hamilcar’s daughter pursues me! I am afraid of her, Spendius!” He pressed himself close against his breast like a child terrified by a phantom. “Speak to me! I am sick! I want to get well! I have tried everything! But you, you perhaps know some stronger gods, or some resistless invocation?”

“For what purpose?” asked Spendius.

Striking his head with both his fists, he replied:

“To rid me of her!”

Then speaking to himself with long pauses he said:

“I am no doubt the victim of some holocaust which she has promised to the gods? — She holds me fast by a chain which people cannot see. If I walk, it is she that is advancing; when I stop, she is resting! Her eyes burn me, I hear her voice. She encompasses me, she penetrates me. It seems to me that she has become my soul!

“And yet between us there are, as it were, the invisible billows of a boundless ocean! She is far away and quite inaccessible! The splendour of her beauty forms a cloud of light around her, and at times I think that I have never seen her — that she does not exist — and that it is all a dream!”

Matho wept thus in the darkness; the Barbarians were sleeping. Spendius, as he looked at him, recalled the young men who once used to entreat him with golden cases in their hands, when he led his herd of courtesans through the towns; a feeling of pity moved him, and he said —

“Be strong, my master! Summon your will, and beseech the gods no more, for they turn not aside at the cries of men! Weeping like a coward! And you are not humiliated that a woman can cause you so much suffering?”