Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

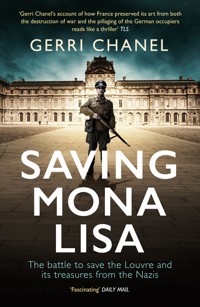

In August 1939, curators at the Louvre nestled the world's most famous painting into a special red velvet-lined case and spirited her away to the Loire Valley as part of the biggest museum evacuation in history. As the Germans neared Paris in 1940, the French raced to move the masterpieces still further south, then again and again during the war, crisscrossing the southwest of France. Throughout the German occupation, the museum staff fought to keep the priceless treasures out of the hands of Hitler and his henchmen, often risking their lives to protect the country's artistic heritage. Saving Mona Lisa is the sweeping, suspenseful narrative of their struggle.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 459

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SAVING MONA LISA

THE BATTLE TO PROTECT THE LOUVRE AND ITS TREASURES FROM THE NAZIS

GERRI CHANEL

Above all, France was obliged to save the spiritual values it held as an integral part of its soul and its culture. To put its artworks, its archives and its libraries out of harm’s way was indeed one of our country’s first reflexes of defense.

— ROSE VALLAND, Le Front de l’Art

There are fights that you may lose without losing your honor; what makes you lose your honor is not to fight.

— JACQUES JAUJARD, Feuilles

CONTENTS

MUSÉE DU LOUVRE

PRIMARY LOUVRE STORAGE DEPOTS DURING WORLD WAR II

PRINCIPAL LOUVRE STORAGE SITES DURING WORLD WAR II, AND THE PARTITION OF FRANCE JUNE 1940 TO NOVEMBER 1942

ITINERARY OF THE MONA LISA

September 1938 Paris to Chambord

September 1938 Chambord to Paris

August 1939 Paris to Chambord

November 1939 Chambord to Louvigny

June 1940 Louvigny to Loc-Dieu Abbey (Martiel)

October 1940 Loc-Dieu to Montauban

March 1943 Montauban to Château de Montal (Saint-Jean-Lespinasse)

June 1945 Montal to Paris

SELECTED INDIVIDUALS & ORGANIZATIONS

INDIVIDUALS – EARLY ROLES DURING WORLD WAR II

FRENCH

Marcel Aubert Curator of the Louvre’s Department of Sculptures.

Germain Bazin Assistant curator of the Louvre’s Department of Paintings, reporting to René Huyghe; head of art depot at the château de Sourches.

Joseph Billiet Assistant director of the Musées Nationaux (French National Museums), reporting to Jacques Jaujard, director.

Jacqueline Bouchot-Saupique Art historian and professor at the École du Louvre; also served as Jacques Jaujard’s assistant during the war.

Abel Bonnard Appointed Minister of National Education in April 1942, replacing Jérôme Carcopino. The French Fine Arts Administration fell under his purview.

Jérôme Carcopino Minister of National Education 1941 to 1942, replaced by Abel Bonnard.

André Chamson Until the war, assistant curator at Versailles; also a writer. Resided at the Louvre evacuation depots with his wife, Louvre archivist Lucie Mazauric.

Christiane Desroches Noblecourt Louvre staff member specializing in Egyptology.

Carle Dreyfus Curator of the Louvre’s Département des Objets d’art and first depot director at Valençay.

Hans Haug Depot director at Cheverny as of 1940.

Louis Hautecoeur Secretary General of Fine Arts from summer 1940. The French national museum system—including the Louvre—was under his control. He reported to the Minister of National Education. Replaced spring 1944 by Georges Hilaire.

Magdeleine Hours Louvre staff member specializing in painting restoration.

René Huyghe Head curator of the Louvre’s Department of Paintings, reporting to Jacques Jaujard. Head of various Louvre evacuation depots.

Jacques Jaujard Appointed acting director of the Musées Nationaux in December 1939 and director in September 1940. Responsible for the Louvre. Reported to the Secretary General of Fine Arts, Louis Hautecoeur.

Suzanne Kahn Jaujard’s assistant when the war began.

Lucie Mazauric In charge of the Louvre archives. Resided at the Louvre evacuation depots during the war; married to André Chamson.

Pierre Laval Vichy Prime Minister June to December 1940 and April 1942 to August 1944, reporting to Head of State Philippe Pétain.

Philippe Pétain Head of Vichy government.

Pierre Schommer One of the senior administrators of the French national museum system; head of the Chambord evacuation depot.

Charles Sterling A curator in the Louvre’s Department of Paintings; assigned to the evacuation depots.

Rose Valland Volunteer staff member at the Jeu de Paume Museum.

Gérald Van der Kemp Louvre staff member; appointed head of the Valençay evacuation depot in autumn 1940.

Henri Verne Director of the Musées Nationaux from 1926 to 1939; succeeded by Jacques Jaujard in 1940.

GERMAN

Otto Abetz Appointed German ambassador to France in 1940. Ally of Joachim von Ribbentrop.

Hermann Bunjes Art historian assigned in 1940 to Kunstschutz art protection agency, reporting to Franz von Wolff Metternich. Ally of Hermann Göring.

Karl Epting Worked for Otto Abetz as a cultural advisor.

Joseph Goebbels Hitler’s Reich Minister of Propaganda.

Hermann Göring Hitler’s second-in-command and head of the Luftwaffe, the German Air Force.

Heinrich Himmler Overseer of the Gestapo, the SS and the Ahnenerbe cultural research group

Felix Kuetgens A senior member of the Kunstschutz.

Otto Kümmel Director of the Berlin State Museums and head of the project to identify certain art of German “origin” located in other countries.

Joachim von Ribbentrop Hitler’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Alfred Rosenberg Official philosopher and racial theorist of the Nazi party; in summer 1940, also appointed head of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR).

Bernhard von Tieschowitz Second-in-command at the Kunstschutz.

Count Franz von Wolff Metternich Head of the Kunstschutz, effective spring 1940.

ORGANIZATIONS

FRENCH

Forces Françaises Libres (FFL—Free French Forces). Resistance group led by Charles de Gaulle from his base in London.

Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (FFI—French Forces of the Interior). Formed upon the unification of a number of Resistance groups in February 1944.

Milice Vichy-sponsored secret paramilitary force.

Musées Nationaux (French National Museums system). Umbrella organization for all French state-owned museums, including the Louvre and other museums such as Cluny, Jeu de Paume, Guimet, Musée d’Art Moderne and Versailles. Later in the war, provincial museums also came within its purview. Jacques Jaujard was director of the system during the war. The Musées Nationaux was under the auspices of the Fine Arts Administration, which, in turn, was under the control of the Ministry of National Education.

Vichy regime The pro-Nazi French government created in the summer of 1940 under the leadership of Philippe Pétain. Named for the central France town in which the regime had its headquarters.

GERMAN

Ahnenerbe Research group dedicated to substantiating Hitler’s belief in the existence of a lost Aryan master race from which, according to Hitler, modern Germans were descended. Headed by Heinrich Himmler.

Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR—Reich Leader Rosenberg Taskforce). Nazi Party organization dedicated to appropriating cultural property; led by Alfred Rosenberg.

Kunstschutz Unit of the German armed forces (Wehrmacht) responsible for the protection of monuments, works of art and other items in occupied territories.

PROLOGUE

THE LOUVRE IS the most visited museum in the world. When the vast majority of its almost 10 million annual visitors come to pay homage to the Mona Lisa, Venus de Milo, the Winged Victory of Samothrace and the breathtaking array of other masterpieces, they take for granted that the collections have always been calmly and majestically on view, but nothing could be further from the truth, for the Louvre lies in a city that has known much war.

At 5 p.m. on August 25, 1939, nine days before France declared war against Germany, the Louvre closed its doors to visitors. Moments later, a small army of museum staff and volunteers began toiling around the clock to unmount, wrap and crate some of the world’s most precious art and antiquities as they launched the largest museum evacuation in history. At 6 a.m. three days later, convoys of trucks began spiriting away the Louvre’s treasures to châteaux in the Loire Valley. Items were marked with a system of dots: two red dots for those with the highest evacuation priority, green for the most significant among the rest and yellow for lower priority works. Of the many thousands of treasures, only a single one had three red dots, the painting about which a biographer of Leonardo da Vinci once said, “If it were decreed that all the paintings in Europe save one must be destroyed, we know which one would have to be saved.”

The Mona Lisa left in the first convoy, set first into a custom-made poplar case cushioned inside with red velvet, then packed carefully into her crate. During the six years of her exile, she would be moved six times, each time with baited breath. At the countryside depots, she would often sleep at the bedside of curators who were painfully aware of the heavy responsibility they held for one of the world’s most famous and valuable pieces of art.

Over 3,600 paintings would be evacuated from the Louvre, along with many thousands of drawings, engravings, sculptures, antiquities and objets d’art, plus the museum’s archives and much of its library. The initial steps of the operation would unfold in large part like a well-rehearsed ballet due to almost a decade of intensive planning.

But an evacuation can be planned, a war far less so. The administrators of the Louvre could not know what plans the Germans would have for France’s art during the Second World War or that they would also have to battle the leaders of France’s Vichy government. For six years, the Louvre’s directors and its staff would risk their jobs and, in many cases, their lives, to protect the artworks and the Louvre palace not only from the personal appetites of the German leaders but also from bombing, fire, flood, theft and the viciousness of German military reprisals. This is their story.

THEMONA LISA IN HER CASE

PART I

FROM WAR TO WAR

Fall 1187 to Summer 1938

ONE

PROTECTING PARIS, PROTECTING ART

THE LOUVRE OWES its existence to the military prowess of a twelfth-century Egyptian sultan who never set foot in France: Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, also known as Saladin. In October 1187 he captured Jerusalem; within weeks, the Pope called the kings of Europe and lesser nobles to embark on the Third Crusade to reconquer Jerusalem from Saladin. Both monarchs knew the fight could mean an absence of years from their territories, a particularly sensitive point for King Philippe Auguste of France, who had long been fighting with England over territory not far from Paris. During the long preparations for the Crusade, Philippe considered how he might gain an advantage over the English when the Crusade was over and they would inevitably begin battle again.

A week before he departed for war in June 1190, Philippe commanded the bourgeois of Paris to build, in his absence, a strong, high wall to encircle the city’s developed area north of the river Seine. Philippe realized, however, that there would be a weak point in the defense where the western edge of the wall met the river, which runs through the city horizontally and then on towards Normandy, the direction from which the English were likely to attack. His solution? Build a fortress where the wall met the river and surround it with a moat. He named his fortress the Louvre.

PORTRAIT OF FRANÇOIS I, JEAN CLOUET (C. 1513)

LOUVRE, RICHELIEU WING, SECOND FLOOR

By the late 1300s, the Louvre’s defensive function was made obsolete by Charles V’s new wall around a growing Paris. The king transformed the dark fortress into a larger, brighter royal residence with elaborately carved windows and ornately decorated rooftops. After Charles, the castle fell into a long period of neglect that made an abrupt about-face during the reign of François I, who took the throne in 1515. François set plans in motion for a sumptuous Renaissance palace. He began by demolishing Philippe Auguste’s massive keep to make way for a central courtyard to host Renaissance feasts. The courtyard and the buildings around it would later be enlarged and renamed the Cour Carrée; they would later bear witness to some of the most dramatic events at the museum during World War II.

François was also an art patron who sponsored an Italian named Leonardo da Vinci. When da Vinci’s previous patron died in March 1516, François invited the artist to France, offering him the title of First Painter and Engineer and Architect of the King. The 64-year-old da Vinci made the three-month journey from Italy by mule, accompanied by his two assistants and carrying along his notebooks and at least three of his paintings: Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, Saint John the Baptist and Mona Lisa. All three works legally came into François’ hands shortly after da Vinci’s death three years later. The king’s collection of paintings was small—perhaps less than 100 paintings—but it had a large stature. The château of Fontainebleau, which then housed most of the works, became a noted cultural center to which distinguished visitors streamed from across Europe. This small but prestigious collection formed the seed that would grow into the Louvre Museum.

REBELL IOUS SLAVE, MICHELANGELO (C. 1513)

LOUVRE, DENON WING, GROUND FLOOR

In the 250 years after François’s reign, the Louvre palace grew exponentially. In the early 1600s its footprint stretched west when Henri IV built a one-third-mile-long gallery along the Seine—eventually called the Grande Galerie—to connect the Louvre with the nearby Palais des Tuileries (Tuileries Palace). At a cost of half the annual budget of the kingdom, the gallery had been conceived by the former queen, Catherine de Medici—who died long before it was finished—simply so that she could move between the two palaces without enduring bad weather or curious eyes. Henri’s successor Louis XIII built, among other construction, the Pavillon de l’Horloge (Clock Pavilion), which extended the Cour Carrée. In late August 1944, the French museum administration would gather in the Cour Carrée in front of the Pavillon de l’Horloge to raise the French flag atop its roof when they believed—erroneously—that danger to the museum and its staff was over.

Under Louis XIV, the palace spread east; Louis was also responsible for an exponential growth in the royal art collections. However, many pieces, like the Mona Lisa, were stored or displayed at Versailles, having been moved from Fontainebleau by Louis long before. It would take a revolution to create the Musée du Louvre and to bring the Mona Lisa to Paris.

The museum, which opened to the public in November 1793, displayed only a fraction of the items from the former royal collections; Mona Lisa remained at Versailles. A few of the items on display at the new museum came from François I’s original collection, but most items on view and many of the additional items that would soon join them came from later royal acquisitions and from items seized during the Revolution from aristocratic families who had fled France. Two such pieces were Michelangelo’s 7-foot-high Slave sculptures. In 1794, additional art and antiquities began to arrive, looted from Belgium by France’s Revolutionary troops.

But the plunder of the former French aristocracy and Belgium would pale in comparison to the pillaging across Europe by Napoleon Bonaparte beginning in 1796, much of which was hauled to the Louvre. A great deal of the loot came from Germany and Austria. Although later treaties legally allowed France to retain some of these items, Adolf Hitler and his art experts would begin plotting in the 1930s to get them back.

Napoleon’s river of plunder flowed to Paris for more than a decade. One of his greatest acquisitions arrived at the Louvre in 1797: Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana, a sixteenth-century portrayal of the New Testament story of the wedding feast in Galilee at which Jesus turned water into wine. The massive 32-foot-long by 22-foot-high work, which had been displayed in the rectory of Venice’s San Giorgio Maggiore monastery for 235 years, was sliced in half by Napoleon’s troops to make it easier to haul back to France.

Later the same year, the Mona Lisa finally left Versailles for the Louvre. Several years later, the painting was moved to the apartments of Empress Josephine in the Palais des Tuileries, then returned once again to the Louvre when Napoleon had himself crowned emperor of France in 1804. Napoleon also installed a new museum of antiquities in the palace, furnished in part with additional items from Versailles, such as the 2,000-year-old marble sculpture of the goddess of hunting, Artemis with a Doe (also known as the Diana of Versailles), which had been a gift from Pope Paul IV to Henri II.

WEDDING FEAST AT CANA, PAOLO CALIARI, KNOWN AS VERONESE (1562–1563)

LOUVRE, DENON WING, FIRST FLOOR

During his glory years, Napoleon undertook major renovations both inside and outside the palace. He also had a grand vision for its development that included, among other features, long new wings running along the new rue de Rivoli to finally connect the Palais des Tuileries to the Louvre. But the plan remained dormant because by 1815, defeated at Waterloo, Napoleon’s glory days were over. When Napoleon fell from power, more than four thousand pillaged paintings, sculptures, objets d’art and antiquities in the Louvre went back to their rightful owners. The works that remained did so legally under the terms of treaties negotiated at the end of hostilities. Of all the paintings Napoleon had taken, only one hundred or so would remain in France, among them Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana, which ultimately was considered too fragile to travel. Instead, the monastery from which it had come accepted a large painting by Le Brun in exchange. In 1939, Veronese’s masterpiece would be spirited away from the Louvre with more care than Napoleon’s troops had taken; curators would roll it carefully—and intact—onto a giant oak column.

When Napoleon fell, so did the Louvre’s first museum director, Vivant Denon. Denon’s successor set out to replenish the museum. One of the major acquisitions of the 1820s was an ancient Greek statue of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty, called Venus by the Romans. The almost 7-foot-high Venus de Milo was discovered in 1820, buried in a field among other ancient ruins on the Greek island of Melos. Other works acquired in the same era included the 3,100-year-old pink granite sarcophagus of Ramses III and Géricault’s giant Raft of the Medusa, depicting the wreck of a French frigate off the coast of Senegal in 1816 with over 150 men on board. During the great evacuation of 1939, the painting itself would almost be destroyed.

In July 1830, the Louvre was stormed during a revolution in which King Charles X was overthrown and replaced by Louis Philippe, Duke of Orleans. As agitation stirred, insurgents headed towards the symbols of power: City Hall, the Palais des Tuileries—the king’s residence—and the Louvre. By evening, angry crowds lined the long stretch of the Grande Galerie and the eastern, Colonnade end of the Cour Carrée. It was the first time the Louvre’s artwork was at significant risk, and, astoundingly, nobody had ever considered how to protect it.

After assessing the volatile scene along the quai from a window of the Grande Galerie, the museum’s secretary general, 93-year-old Vicomte de Cailleux, instructed the museum guards to start taking down the paintings immediately. Museum practice at that time favored paintings hung from floor to ceiling, requiring the guards to work through the night and into the morning, climbing up and down ladders to empty the packed walls. Shortly thereafter, crowds forced their way into the palace in search of royal troops. Once inside, they surged through the museum, shooting out door locks to get into closed rooms. In the midst of the agitation, the Vicomte de Cailleux placed some small signs at the entrance to the Louvre with a short, simple request for the insurgents: “Respect the national property.”

RAFT OF THE MEDUSA, THÉODORE GÉRICAULT (SALON OF 1819)

LOUVRE, DENON WING, FIRST FLOOR

And with minor exceptions, they did. Only several items were mutilated, simply because they represented the monarchy. Likewise, there was minimal looting, given the size of the crowd, the magnitude of the treasures and fact that most of them had been left virtually unguarded after Swiss Guards assigned to the palace left to protect other Parisian buildings.

July 1830 had been a violent month for the Louvre; the year finished violently as well. On the night of December 21, thousands of insurgents again pressed towards the doors of the palace after learning that Charles X’s ministers, after being put on trial, had avoided a death sentence. A large number of guards had been readied in the Cour Carrée. When angry crowds arrived, this time the doors remained shut tight.

In February 1848, the Duke of Orléans was ousted in yet another revolution. Around the Louvre, the scene was eerily reminiscent of July 1830 as crowds surged through the Tuileries.Some of the insurgents again made their way into the adjacent Louvre, where artworks had been stacked along the walls of the Grande Galerie in preparation for an upcoming exhibition. Along the parquet floor in front of the piles of paintings, the curators had quickly written a message in chalk: “Respect à la propriété nationale et au bien des Artistes” (Respect the national property and the interests of artists). Of all the unguarded works of art, some of them great masterpieces, amazingly not a single one was touched or damaged except for one small German work.

Late that year, Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, became France’s first elected leader. By 1852, after a coup d’état, he was Emperor Napoleon III. Under his rule, the Louvre again exploded in size, including new long wings finally linking the Louvre and Tuileries as Napoleon Bonaparte had envisioned. A number of galleries received elaborate décor, including a massive painting, Apollo Slays Python, designed and executed by Delacroix for the central ceiling area of the luxurious Apollo Gallery.

THE SEATED SCRIBE (C. 2620–2500 BC)

LOUVRE, SULLY WING, FIRST FLOOR

The Louvre also made some spectacular acquisitions during that era, including, in 1852, Boucher’s Diana Leaving her Bath, a painting of the Roman goddess of the hunt and one which Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s minister of foreign affairs, would later covet. Two years later came the almost 2-foot-high, ancient painted limestone sculpture, the Seated Scribe, a gift from the Egyptian government.

In 1863, the museum acquired the 9-foot-high marble Winged Victory of Samothrace, portraying Nike, the Greek goddess of victory at the prow of a 9-foot-high ship. The work had been named after the island on which the 2,000-year-old sculpture was discovered in 1863. After reassembling the statue’s 118 pieces, not including the ship’s prow, which was excavated and acquired over a decade later, the Louvre put the Winged Victory on display in the Cour Carrée’s Salle des Caryatides in 1866. Workers would later move it to the top of the monumental Daru staircase from which it would descend in 1939.

WINGED VICTORY OF SAMOTHRACE (C. 190 BC)

LOUVRE, DENON WING, ESCALIER DARU, GROUND–FIRST FLOOR

Until 1870, the Louvre peacefully grew its collections, then came war once again, after tensions between Prussia and France escalated. On July 18, 1870, Napoleon III declared war on Prussia, after which various German states quickly joined Prussia. It was reasonable to conclude that if the Germanic armies captured the city, they would loot the Louvre just as Napoleon’s armies had done in Prussia. On August 30 the government quickly decided to evacuate the most precious items to military buildings in the far northwest port city of Brest on the Channel coast. From there, they could be quickly evacuated to England if necessary. The 1870 evacuation of the Louvre was the first time such a measure had ever been taken.

The Grande Galerie became a frenzied packing workshop where curators and assistants had what they felt was the impossible task of unframing, packing, crating and shipping several hundred fragile items in four days; in 1939, curators would evacuate thousands of items in a similar amount of time. Readied crates were loaded onto horse-drawn carriages that headed to the train station, accompanied by museum guards in civilian dress rather than their uniforms in order to draw less attention. The first pieces of art left for Brest on September 1. Among the items aboard were the huge—and rolled—Wedding Feast at Cana and the Mona Lisa. Over the next several days, additional crates headed towards Brest.

In mid-September, by which time 123 crates had safely reached Brest, authorities called off further evacuation amid concerns that crates in transit to the train station would be hijacked by insurgents for use as barricades. Attention then turned to protecting the palace itself and the art and antiquities still within. Ground-floor windows deemed to be vulnerable to enemy fire were sheathed with sandbags, as were some of the exterior architectural sculptures. The most valuable remaining works of art and antiquity were either moved to hallways or brought down to ground-floor rooms and to basement areas judged by palace architects to offer the most strength against enemy projectiles. In the Egyptian gallery, jewels and papyrus were tucked inside the same sarcophagi that would hide something far more volatile during World War II.

By mid-September 1870, Prussian troops had completely encircled Paris with the intent of starving the city into surrender. The siege went on for months. By the start of 1871, the enemy began pounding the outskirts of the city with cannon fire and launching shells into the city itself. At midnight on January 6, Louvre officials spirited Venus de Milo out of the museum and arranged for a hiding place in the basements of a nearby police building. At the end of January, the French finally surrendered and a three-week armistice was declared, during which a new government, the Third Republic, was formed, headed by Adolphe Thiers. The new government agreed to a humiliating preliminary peace treaty with Prussia, signed at Versailles in February 1871, but peace in the city was short-lived.

Many Parisians suspected that the new government was planning to restore the monarchy and there was widespread discontent with the terms of the treaty. In mid-March, just as the Louvre was preparing to return the evacuated items from Brittany, civil war erupted after Thiers moved his government to Versailles and tried to disarm Paris. A loose confederation of socialist and reformist groups took control of the city and formed their own government: the Paris Commune. Through April and into May, violence escalated as Thiers’s forces tried to take back the city. After a bloody massacre of Communards ensued on May 21, their compatriots began to torch public buildings across the city.

PANORAMA DE PARIS. INCENDIE DESTUILERIES, 24 MAI 1871, ANONYMOUS, LOUVRE’S COUR CARRÉE AT REAR, GRAND GALERIE AT RIGHT, PARALLEL TO THE SEINE, ENGULFED IN SMOKE

MUSÉE CARNAVALET

In the early evening of May 23, insurgents rolled carts full of gunpowder, turpentine and paraffin oil into the Palais des Tuileries, spread it onto floors, stairways, wood paneling and draperies across the palace and set it all ablaze. The fire quickly spread out of control into a spectacular inferno that destroyed the palace’s floors, roofs and contents. The blaze also threatened to swallow up the adjacent Louvre. It spread partway along the wings bordering rue de Rivoli before it was extinguished there, reducing 80,000 volumes of the library to ashes. The fire also spread across the rooftops and roof joists to the wings along the Seine, licking at the roofs of the Grande Galerie. The curators and firefighters knew that if the fire propagated further it would quickly reduce the museum’s art to ashes.

The collections were at particular risk due to shockingly inadequate fire protection measures. Minor protective measures had been taken following a 1661 fire in the Petite Galerie, but a hundred years later, in spite of years of pleas by curators, the Louvre still did not have an adequate system of fire protection. The museum would likely have been lost but for the courage of curators willing to enter the burning building to identify a point where firefighters might isolate the blaze from the Grand Galerie. A battalion of 100 men then formed a relay—while surrounded by Communards threatening to shoot—and delivered enough water to extinguish the flames.

In September 1871, the 123 crates of artwork that had been evacuated to Brest the previous year were returned to Paris; the Mona Lisa was placed in the Salon Carré, the room off the eastern end of the Grande Galerie where she had made her very first appearance at the Louvre at the end of the 1700s. Venus de Milo was returned from the police building under which she had safely survived both war and revolution. The Louvre turned to repairing damage from the fire (demolition of the last vestiges of the Tuileries was authorized in 1882) and to the work of running and growing a museum.

Earlier in 1871, Thiers’s government had signed a final peace treaty with Germany. One of its provisions required France to pay the staggering sum of 5 billion gold francs as war reparations; it also stipulated that German troops would remain in France until the obligation was discharged. By September 1873, the debt had been paid in full and the last German soldiers left France. In 1914 they would be back.

TWO

WORLD WAR I

IN THE VERY early years of the twentieth century, the Louvre was not under immediate threat of war, but it faced other risks. Theft, for one. Fewer than 150 guards protected collections spread across almost eight acres of exhibition space. Other security measures were also shockingly weak. Mona Lisa had been covered with glass in 1907 for protection against vandalism but like the other paintings in the museum it was attached to the wall only by several hooks. The artworks were not more strongly secured, a director of the museum had said, because the Louvre was not built to be a picture gallery: it was not fireproof and there was an even higher risk of fire since there were other users of the building. In case of fire, he said, the paintings could be quickly pulled off the walls and taken to safety.

There were other security problems as well. Any official photographer could carry off a painting to the building’s photo studios without permission or an escort and a notice of explanation was not required to be posted if a work had been removed. Moreover, there was no alarm system and numerous passkeys opened every door in the museum. In early 1911, a reporter successfully hid overnight in a sarcophagus to expose the lax security. No precautionary measures were taken in response.

Just before closing time at the Louvre on Sunday August 21, 1911, a man slipped into a supply closet. Early the following morning, he slipped out of the museum with the Mona Lisa. The theft went unnoticed for more than twenty-four hours and, once it was discovered, all leads soon went cold. In December 1913, the painting was finally found in Florence, Italy, where the thief had recently taken it. The culprit, Vincenzo Peruggia, was a handyman with a minor arrest record who had briefly worked at the Louvre in 1908, helping to protect the artworks with glass. For more than two years, police had speculated that the Mona Lisa had been spirited away to a foreign buyer by a sophisticated ring of international art thieves. But all that time, the Mona Lisa had been just over a mile away from the Louvre, tucked away in a false-bottomed wooden box in Peruggia’s room in a rundown Paris rooming house. In late 1913, after Peruggia took her to Italy in hopes of arranging a sale, authorities apprehended him and retrieved the painting.

Mona Lisa enjoyed brief but wildly popular viewings in Florence, Rome and Milan before being prepared for her return to her adopted home. She had first crossed the border from Italy to France in late 1516. At 3 a.m. on New Year’s Day, 1914 she crossed the border again, this time by train instead of mule. On January 4, after great celebration, she was back on display at the Louvre, surrounded by record crowds—and better security measures.

Six months later, France was no longer celebrating. Instead, the country was facing imminent war with Germany, following a spiral of events after the June assassination of the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand. On July 31, only one day before Germany declared war on Russia and three days before Germany and France declared war on each other, Henri Marcel, the director of the Musées Nationaux, wrote a confidential report indicating the need to secure the art of the national museums and, above all, of the Louvre. He pointed out that the risks were even more serious than in 1870 due to advances in explosive devices and aeronautics, including the projectile-laden German Zeppelin.

The next day, action was taken to protect the most precious pieces of the museum. As in 1870, workers moved some items under vaulted arches, others to recesses in particularly thick walls and yet others to the floors below. Certain works were sheltered in place by timber-framed sandbag fortresses and workers once again piled sandbags against sculptures and windows to protect against explosions.

The German army advanced into France on August 24. At noon the following day, Marcel urgently gathered the museum curators to assign new instructions, this time to prepare as many paintings and other works of art as possible for shipment to Toulouse in southwest France. By August 28, the staff were told to do it faster and at any cost. One curator said that the crating process felt like filling and nailing coffins.

On August 30, two hours were needed just to remove David’s immense (20 by 32 feet) Coronation of Napoleon from its frame and supports and roll it onto a large wooden cylinder. That evening, in spite of frenzied, non-stop activity, a government minister told them to work even faster. Venus de Milo was brought down from her base and readied to leave the palace as in 1871, though this time she left in broad daylight rather than under cover of darkness. And instead of heading towards a secret tomb in Paris, she was loaded into a wagon and put on a train for Toulouse along with other works. The following day, crate number 6 was prepared. Into it went, among other works, Clouet’s François I and finally—under heavy watch—the MonaLisa. The Wedding Feast at Cana, considered too large to move, would remain in place for the duration of the war.

LOUVRE ARTWORKS IN JACOBINS CHURCH, TOULOUSE, WORLD WAR I

On September 1, vehicles arrived and the loading process began. After they ran out of crates, artwork was loaded bare into trailers. Loading continued the following day. Curator Paul Leprieur wanted to hold back a fragile drawing; he said he had faith in the hiding places of the Louvre and that he would lie to the enemy to have them believe that the artwork had been removed. “But if this was discovered,” other staff members asked him, “do you know what you risk?” “Oh well, yes,” Leprieur replied, “maybe they’ll shoot me, that’s all.” He would die in service to the Louvre, though not as he speculated, ultimately suffering a fatal fall on one of the museum’s staircases in May 1918.

Towards 6:30 p.m., as the staff were loading the last vehicle, they saw a German plane flying over the Louvre. The containers holding Venus de Milo, 770 evacuated paintings and drawings and two crates of objets d’art were loaded onto four train cars at the gare d’Austerlitz. Venus de Milo, packed carefully in a wooden crate, traveled in her own wagon. As the train prepared to leave for Toulouse, the staff at the Louvre could hear the distant, heavy sounds of the large artillery of the Germans through the open windows of the galleries.

The evacuated items—a tiny proportion of the Louvre’s holdings compared to what would be evacuated on the eve of World War II—safely reached Toulouse, where they were stored under the soaring vaulted arches of the medieval Jacobins Church, most of the artwork remaining in the wagons in which they had traveled from Paris.

Back in Paris, some areas of the museum were used to store items evacuated from other museums. Behind the scenes, waiting for the war to end, the museum updated some of the galleries and continued to acquire new pieces. Twice during the war, the museum opened a few galleries to the public, mainly exhibiting sculptures that had remained behind. However, it closed at the end of January 1918 after German bombers conducted their first raid on Paris. The Louvre was hit, although the administration was relieved to find that the projectiles had not penetrated to the lower levels where the art was stored.

In March 1918, as the Germans began to fire upon the city with new, huge long-range cannons, additional evacuations brought artworks to the château de Blois. In June, as the cannons drew perilously close to Paris, the museum’s administration decided to try to evacuate as much as possible of what had remained. This was not an easy task since much had stayed behind, including almost all the antiquities. On June 6, Georges Bénédite, curator of the Department of Egyptian antiquities, issued a bold appeal to the director of the Louvre that his department’s items finally be evacuated. He noted that his department had a number of items far more valuable than the paintings that had gone to Blois, “a value not only artistic, but monetary,” citing, among others, the ancient Egyptian Seated Scribe. He ended his request with a final personal plea: “I have not left my post since the declaration of war, I have not taken any kind of time off, nor left Paris for a single night, I believe that I have the right to ask for assistance at such an urgent and difficult moment.”

The evacuated items in Toulouse were joined in August 1918 by one final shipment of artworks that had been sent from Paris amid ongoing fears of air raids. There and in Blois, the collections waited out the final months of the war. On November 11, 1918, as cannons and church bells announced the signing of an armistice, preparations began to return the artworks. Less than five weeks later, crates began heading back to Paris. The Louvre progressively reopened during January and February 1919 as the public enthusiastically returned to galleries that had been cleaned, reorganized and enriched.

The Louvre and its artwork had escaped another war without destruction or significant damage and life at the museum was soon back to normal. However, by the early 1930s French fine arts authorities were worrying once again about war with Germany and the accompanying risks to French museums and collections. This time, however, they would not wait until three weeks before a declaration of war to develop protection plans; this time they would begin almost a decade ahead.

THREE

DRUMS OF ANOTHER WAR

THE TREATY OF Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, officially ended the war between Germany and France and the Allied powers. Among its other provisions, the treaty required Germany to make substantial concessions of territory, to pay reparations to various countries and to disarm. As the Germans signed the treaty, they were outraged about its terms but did not have the military strength to object. As the Allies signed, they knew that peace might be precarious. Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Commander of the Allied Armies, prophetically said of the treaty, “This is not peace; it is an armistice for twenty years.”

As early as May 1920, the French considered creating a fortified zone along the border between Germany and France; by 1930, in a project championed by André Maginot, France’s minister of war, construction of massive fortifications began along the border. The French put their hopes for protection from Germans in a future war into the Maginot Line. It would prove to be a false hope: when war finally would come, the Germans would simply swing north and bypass it.

After the onset of the world economic depression in 1929, France and the rest of Europe watched the continuing rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party. The French fine arts administration was watching as well—and unlike in previous wars, they were not about to wait to develop a plan to protect the country’s art until an enemy was only miles away. In February 1932, the fine arts administration agreed to work with Paris civil authorities on a plan for protecting the city’s museums. France was not alone in its preparations; as early as 1929, the Dutch had requested a study of ways to protect its national collections and in 1933 the British were discussing air raid precautions.

Concern and planning escalated apace with developments in Germany. In the July 1932 German elections, the Nazi party—with Hitler at its helm—became the largest party, though not yet a majority, in the German parliament. Shortly thereafter, Henri Verne, director of the Louvre and the other museums in the Musées Nationaux system, sent confidential letters to curators asking them to make priority lists of the works to be evacuated in case of “an eventuality that must be expected, even while hoping it will not happen.”

On January 30, 1933, tens of thousands of Nazi troops marched in a torch-lit parade through the streets of Berlin to celebrate Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany. Within six months, French authorities forecast the most likely areas of military action and museum authorities used the information to begin identifying safe locations for art evacuation depots. Verne established an evacuation plan for the French national museums’ treasures and a plan for items to be protected in place. Before the end of the year, he was also considering the effects of German incendiary bombs and by spring 1934, the fine arts administration was considering specifications for bomb shelters to protect its employees. They were right to be concerned: In November 1936, during the Spanish Civil War, the Prado Museum would be hit by nine German-built bombs within a single hour.

Early in the planning process, it became clear that it would simply not be realistic to evacuate all the art and antiquities from the Louvre, much less from Versailles and the other museums under the auspices of the Musées Nationaux. There would be neither enough money, people, materials or vehicles in the event of war to move them all, nor enough appropriate places to store them. Thus the first challenge was deciding what to evacuate and what to leave in place. For curators, with a deep devotion to their art, making priority lists of such treasures was a bit like asking a parent to choose their favorite child. The most valuable objects in monetary or artistic terms were obvious preferences but selections also had to take into account the size, weight and condition of individual pieces. A number of the Louvre’s pastels were considered too fragile to travel any distance and even as war was declared in September 1939, the 8,800-pound Winged Victory of Samothrace was considered too heavy to evacuate at all.

The next challenge was determining where to store the evacuated treasures. Fine arts administrators concluded that storage depots should be far from anticipated front lines of combat as well as from potential Paris-area bombing targets; to identify such areas they would consult with military authorities. Based on the military’s assumption that the Germans would enter France from the east, depot locations in the center and west of France were considered ideal. On the other hand, it was also important that depots not be inordinately far from Paris or from each other, to facilitate transportation of the works and the movement of curators and staff for restoration and other purposes. Another criterion was that depots should be as isolated as possible, not only far from cities but also from main roads, bridges, industrial sites or any other feature that might be a target for bombing or other military activity.

Specific storage depots then had to be identified; the country’s many châteaux quickly became a clear preference. Often they were in isolated locations and many were perfect strongholds, with vaulted basements and thick stone walls that had stood the test of time. Châteaux were evaluated, in part, on how well curators could control temperature and humidity, not an easy task in old stone castles. Floors had to be strong enough to hold tons of crates; later in the war curators would learn the consequences if this step was overlooked. Potential depots also needed large ground floor rooms and entryways wide enough to easily bring in large items and to remove them just as easily in case of fire, which, after bombing, was by far the most significant concern. And each depot needed a substantial nearby water source in case of a fire. Moreover, any depot or its vicinity had to provide adequate accommodations and food sources for curators and numerous guards, many of whom had families.

By 1933, the Loire Valley, roughly 100 miles south of Paris, had been identified as one of the potentially safest areas for the collections of the Louvre and the other Paris-area museums. The region was both fairly close to Paris and far from the German border and it was also reasonably close to England in the event further evacuation was needed. There were also a great many châteaux that might serve as depots.

Authorities debated whether to use a single large shelter or multiple ones. A single depot would allow concentration of transport, personnel and supplies. On the other hand, multiple depots would be more complicated but would spread the risks of enemy attack and fire. Very early in the planning process, the château of Chambord was chosen as a key location. As one of the largest châteaux in France, it was vast enough to contain everything and, in the midst of miles of surrounding forests, it was isolated enough. It could not be bombed in error because it was easily recognizable from the air and it could be camouflaged easily by smoke if necessary. By February 1934, Chambord had been identified as the primary depot, with collections also to be dispersed among other châteaux. It would also serve as a way station where items would be checked in as they arrived from Paris and then sent onward to their final destinations.

The fine arts administration then had to arrange for the use of specific châteaux. This was not a problem with Chambord, since the French government already owned it, but permission to use others had to be arranged. Subsidies were given to those who granted use of their property, but the amounts were too small to provide much motivation. In some cases, owners were inspired by patriotism or love of art, but more often than not their motivation was to reduce the likelihood that an owner’s castle or manor house would be commandeered or ransacked by the Germans.

Initially, fewer than two dozen châteaux were requisitioned for possible shelter of collections of the Louvre and the other French national museums. Later, provincial collections would fall under the auspices of the Musées Nationaux as well, requiring additional depots. By the end of World War II, more than eighty châteaux—many of them far beyond the Loire Valley—would have served their country for some period of time.

Another issue was transportation. Authorities considered rail transport, which had been used for the World War I evacuation to Toulouse, but there was little enthusiasm for this option. Planners felt that railroads would be encumbered by military transport and supply, as they had been during World War I, and that citizens should have priority access to trains in case of impending war. Moreover, with Chambord as the staging depot, evacuated works would require a secondary transfer from the nearest rail station.

Using barges was also an option, given the multitude of France’s rivers and canals. Proponents argued that barges offered advantages not only over rail transport but also over trucks, which, they said, would face roads clogged by military vehicles and could also break down and catch fire. Barges could also be loaded quickly since the Seine ran right alongside the Louvre. Moreover, it was argued, barges would not be a high-profile enemy target: The enemy would not immediately be looking for them and it was also unlikely that Germans would waste time following their meanderings or attack a random isolated barge. Opposing arguments included the time required for barge transport. Water transport to Chambord would take five or six days while trucks, so it was thought, could get to almost any destination in twenty-four hours. Moreover, as with rail transport, barge transport would still require a secondary transport by truck from canalside to Chambord since studies indicated that the canals were not navigable all the way.

However, evacuation by truck was not an ideal option either. Bridges could be blown, truck convoys could be aerial bombing targets, and roads could be blocked by military vehicles and fleeing civilians, which would later prove to be the case. And in the case of war, there could be (and would be) shortages of both vehicles and fuel. On the other hand, trucks offered the simplicity and speed of a single mode of transport to Chambord and the other depots and assistance could be obtained from companies that specialized in moving works of art.

Ultimately, even up to the weeks just before war was declared in 1939, the museum administration readied trucks for most of the works but still considered barge transport an option for items such as sculptures and certain objets d’art that would not suffer from either humidity or even immersion. In the end, trucks would bring the artworks into exile.

As the 1930s went on, Europe inched closer to war. The Treaty of Ver sailles had set a strict limit on the size of the German military and had forbidden the country to re-arm itself, but Hitler eventually simply ignored most of the treaty. After two years of rearming in secret, Hitler announced in March 1935 that the Luftwaffe had 2,500 warplanes and that he had built up a 300,000-man army and planned to almost double that number. The Treaty of Versailles also banned German troops from certain territory along the Rhine River. In 1936, Hitler again disregarded the treaty as his troops marched into the Rhineland and by year’s end he announced plans to take over Austria and Czechoslovakia. By March 1938, he had annexed Austria and set his sights on the Sudetenland, a former German territory that had become part of Czechoslovakia under the Treaty of Versailles.

By mid-August 1938, the Musées Nationaux were actively mobilizing. They sought trucks for evacuation and made arrangements to lease two large vaults at the Banque de France in Paris for certain fragile items. Huge quantities of crates and packing materials arrived.

After Hitler indicated on September 22 that he would take the Sudetenland, by force if necessary, Europe seemed on the brink of war. The same day, the Musées Nationaux set into motion the measures it had been painstakingly refining since almost the dawn of the decade to protect the art and antiquities from anticipated bombing of Paris. In early evening on Monday, September 26, the Louvre received the long-anticipated evacuation order.

It took the Department of Paintings only an hour and a half to carefully remove from gallery walls every item designated most urgent—including the Mona Lisa—and bring them to packing and crating areas. Some crates had been purposely left temporarily in a hallway with shipping labels noted “New York” in a futile attempt to keep the entire project secret but the extent of the packing and the number of cases and temporary workers were clear evidence of what was actually going on.

At 6 a.m. on September 27, 1938, several trucks loaded with some of the Louvre’s most precious art and antiquities rolled away from the capital towards the château de Chambord. Because military vehicles and road traffic jammed the road as had been feared in the years of planning, it took more than fourteen hours for the convoy to reach Chambord, a distance of only 100 miles.

Aboard the convoy were the crown jewels and other objets d’art from the galerie d’Apollon, plus the essential pieces from the Grande Galerie and the paintings by Rubens that had been commissioned in the 1600s by Marie de Medici, Henry IV’s wife, to depict important events in her life. Also aboard was the Mona Lisa. On her original voyage to France in the sixteenth century, she had traveled in da Vinci’s leather bag. This time she traveled in a special double-walled poplar case, cushioned inside with red velvet, which had been custom made for the evacuation.

As Pierre Schommer, a senior administrator in the Musées Nationaux, unpacked crates at Chambord on September 28, he learned that one of them contained the crown jewels. In light of numerous security concerns, he discreetly took them the following day to nearby Blois and secured them in a Banque de France safe deposit box.

A second convoy of art arrived at Chambord that day and a third came on September 29, as Edouard Daladier from France, Neville Chamberlain from England, and Benito Mussolini from Italy met with Hitler in Munich in a last-ditch effort to avoid war in Europe. On the morning of September 30, as the Chambord staff were unloading crates from the third convoy, they learned of the previous night’s signing of the Munich Agreement, allowing Germany to annex the Sudetenland, thus avoiding immediate war. The furious ongoing packing at the Louvre ceased and within a week, the Mona Lisa, the other artwork at Chambord and the jewels stored in Blois were back in Paris. The Louvre would have eleven months’ grace before war would finally come.