Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

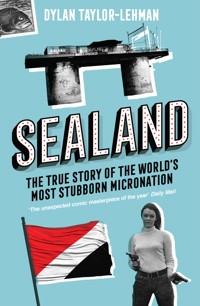

'The unexpected comic masterpiece of the year' Daily Mail In 1967, retired army major and self-made millionaire Paddy Roy Bates inaugurated himself ruler of the Principality of Sealand on a World War II Maunsell Sea Fort near Felixstowe - and began the peculiar story of the world's most stubborn micronation. Having fought off attacks from UK government officials and armed mercenaries for half a century - and thwarted an attempted coup that saw the Prince Regent taken hostage - the self-proclaimed independent nation still stands. It has its own constitution, national flag and anthem, currency, and passports - and offers the esteemed titles of 'Lord' or 'Lady' to its loyal patrons. Incorporating original interviews with surviving members of the principality's royal family, and many rare, vintage photographs, Dylan Taylor-Lehman recounts the outrageous attempt to build a sovereign kingdom by a family of rogue, larger-than-life adventurers on an isolated platform in the freezing waters of the North Sea.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 587

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

To Pamela, wild royalty

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA (FORT)

“It’s no good having weapons if you’re not prepared to use them.”

—Michael Bates

Michael Bates, a fifteen-year-old from a fishing town on the East Anglian coast, stood shivering with excitement and fear on top of an old naval platform seven miles out in the roiling North Sea. It was the middle of the night in late summer 1967, and he had in his hands a beer bottle filled with gasoline and stuffed with a strip of old cloth. The chance to throw a Molotov cocktail at something was any young boy’s dream come true, but in this case it was actually necessary: a small boat bobbing in the sea below was full of men looking to invade his family’s fortress, and Michael alone was tasked with defending it.

The Bates family knew that invasion was likely at any time, and this is why Michael had stashed numerous firebombs along the perimeter wall of the fort he called home. The bombs sat next to chunks of metal and wood to be used for pelting, and there was even a homemade shotgun if things got especially hairy. The invaders had strength in numbers, but Michael had the literal higher ground, from which he could drop the bombs.

The fort was a simple but improbable structure, comprised of a metal deck spanning two massive concrete pillars that rose out of the open ocean. When it was light, Michael could see all the way to the horizon and could easily spot any approaching vessel. He was asleep when the boats puttered over, but, attuned to the sonorous murmurings of the sea, he jumped up from his slumber at the disturbance and ran crouching to the perimeter of the fort.

Oh shit, he thought. Here we go again.

This was at least the sixth time that summer that someone had tried to take over the fort. Originally called Roughs Tower, it was built 2during World War II to protect the Thames channel from Axis bombers. Following the war, the fort sat abandoned in international waters for twenty years until competing groups of pirate radio broadcasters realized how perfect it was for broadcasting outside the UK’s restrictive radio laws. Thanks to subterfuge and straight-up physical force, it was Michael’s family that currently held the reins to this extraterritorial kingdom. Michael’s father—a businessman, war hero, and raconteur named Roy Bates—was the man in charge, and he had indeed launched his own pirate radio station and stashed Michael on the fort to keep it secure.

And so, on that summer night, young Michael stayed low and hidden as the boats puttered in the darkness closer to the huge pillars. He fumbled with a lighter, flicking the flint until he finally ignited the rag in the bottle full of gas.

“It’s no good having weapons if you’re not prepared to use them,” he later said. “Freedom is a very fragile thing.”

As the small yellow dinghy got into a strategic position alongside one of the pillars, Michael smiled sadistically like Kevin in Home Alone and dropped the bomb directly onto the front of the inflatable craft. Tiny points of light were reflected in the occupants’ eyes as the bottle fell in slow motion. Bullseye!

The bottle exploded, the roar of the flames echoing under the fort, the choppy waves illuminated by the glorious orange clouds. The men on the boat yelped and dove into the water as the raft shriveled in the flames, spun in a few circles, and then sunk limply into the abyss. The smell of burned plastic hung in the air, and the trespassers clung helplessly to the rough concrete pillars, trying to protect their heads from the chunks of metal and wood raining down from above.

As the waterlogged invaders were picked up by their comrades and taken back to shore, Michael smiled a huge smile. He was prince of the sea. He had kicked their asses, and he couldn’t wait to tell his dad.

A BURNING BOAT is only the prelude to the adventure, intrigue, and family togetherness that would play out on Roughs Tower for a half century. Michael defended the fort with the same fervor one might a 3homeland, and that’s because it eventually was. Roy Bates saw opportunity in the fort when he took it over, and he realized the scope of that opportunity would be even greater with the authority of statehood. And so, on September 2, 1967, Roughs Tower became the “Principality of Sealand,” the world’s newest and smallest country. Roy became Prince Roy, his wife Princess Joan, and Michael and his sister Penelope, prince and princess. The normal trappings of statehood soon followed, including coins, stamps, passports, a flag, and a constitution. The Sealanders would be joined by many proud citizens over the years—a cast of adventurers, rogues, conmen, and cypherpunks all happy to call the principality home and go head-to-head with the British government.

Sealand has now been around for more than 50 years, “longer than Dubai has been in existence,” as Prince Michael points out. This book is a chronicle of the principality’s storied history, from its pre-Sealand days as a claustrophobic military readout to an experiment in nation-building that has inspired micronations on every continent.

“Our life has always been rich in adventure. You cannot imagine all that took place on Sealand,” Princess Joan said. For starters, there have been weddings, battles, attempted coups, and a half-marathon run on the fort. The principality served as an offshore data haven, challenging internet laws that had yet to be written. The principality’s legal claims have delighted scholars of international law, while others view Sealand as a social experiment on how we might conduct ourselves when climate change forces us to live at sea in Waterworld-ian floating enclaves. Athletes have been proud to compete in the principality’s name, and a Sealand flag even made it to the summit of Mount Everest. But like any nation, there have been numerous challenges to the principality’s leadership: forged Sealand passports have been used in crimes all over the world, and, lurking in the shadows is a bizarre exile government of quasi-Nazi mystics vying to harness a mystical energy called Vril.

Maintaining Sealand introduced enormous amounts of stress and financial hardship to the family and led many to wonder why anyone would hold onto the rusting maritime heap. But the endeavor has been a unique cause to rally around—one that has drawn the Bates family closer together. The story of Roy and Joan Bates is one of storybook 4devotion, a powerful romance filled with ups and downs and schemes and theatrics. The family now boasts a fourth generation of Sealandic royalty: youngsters that have yet to throw firebombs at invading boats but whose lives will no doubt harken the example set by their feisty forebears.

At its very core, the story of Sealand is an inspiring tale of daring and self-determination in a world of homogeneity, a quixotic adventure that has accomplished more than even Roy Bates thought possible. Defending themselves from imperial governments and rapscallion usurpers, Sealanders have always managed to come out on top, and the tiny nation’s motto encapsulates this rogue spirit.

E Mare Libertas: “From the sea, freedom.”

Indeed.

Hunker down in the comfortable surroundings of your own kingdom, and we’ll set sail into the astonishing story of Sealand, the world’s foremost micronation.*

A NOTE ON THE USE OF THE TERM MICRONATION

The term micronation is distinct from “microstate,” which is a tiny country recognized worldwide with membership in international organizations such as the United Nations. Examples of microstates include Andorra, Lichtenstein, and Niue.

A “micronation” is generally defined as an invented country within the territory of an established nation whose boundaries typically go unrecognized on the world stage. Micronations have been declared for reasons serious and tongue-in-cheek alike. Some are a hobby, whose participants roleplay affairs of state, while others are born from arguable claims to disputed lands. Micronations are also called “ministates,” “ephemeral states,” and “counter-countries,” although these terms are less commonly used.

5The Principality of Sealand is often called a micronation and is a respected grandparent of these entities for obvious reasons. However, some argue that the term micronation isn’t serious enough to do the principality justice—Sealand was founded on territory that was in genuinely international waters and has endured since 1967. All the while, the Sealanders have fought to keep these claims alive in ways unmatched by most other micronations.

I will use the term micronation throughout this book when referring to Sealand for reasons of convenience, but the reader can rest assured that I imbue the term with the gravitas the principality is due, as its history can hold its own alongside that of any macrostate.6

*The Principality of Sealand is unrelated to the “SeaLand” often seen on the side of shipping containers. SeaLand is a subsidiary business of Danish shipping giant Maersk and not an economic arm of the principality. “Sealand” also refers to a region of Wales and a Babylonian dynasty, but these entities are unrelated to the story that follows.

CHAPTER 1

THE WAR HERO AND THE BEAUTY QUEEN

“I fought for both sides. I didn’t care, I just wanted to fight.”

—Roy Bates

For months on end in winter and spring 1944, the men of the British Army’s 8th Indian Infantry Division stared up at a monastery in central Italy that hovered over the sodden soldiers like the sigil of a cruel god. The monastery sat atop a promontory of a 5,000-foot-tall mountain, overlooking the Liri Valley and a small town called Cassino. The Nazis occupied the hill and guarded it fiercely with machine gun nests and mines, as it gave them a commanding view of the landscape in every direction and thus control of the resupply route to Rome.

Built in 652 by Benedictine monks, the monastery was preposterously well endowed. With concrete walls 10 feet thick and 150 feet tall, the readout offered a genuinely impenetrable vantage point. A consortium of Allied troops, representing countries as far-flung as Poland, New Zealand, and Nepal, were tasked with wresting control from the Nazis.

The four major attacks on Monte Cassino were legendary in their wretchedness. The only way up the mountain was a path comprised of hairpin turns and jagged, rocky terrain. The first assault was launched in January in the midst of remarkably harsh winter conditions. In the spring the flooded Gari and Rapido Rivers turned the roads into a morass of mud. Frostbite and trench foot were common, and in many cases the “venomous outbursts” of fighting at Monte Cassino amounted to slaughter. Fighting was so concentrated in the ruined town of Cassino below that individual buildings were sometimes occupied by troops from both sides.10

Standing straight-backed and proud among this rank agglomeration of violence and miserable weather was Roy Bates,* age 23, who hailed from Essex, an industrial county studded with shipping warehouses and fishing boats. Roy was a soldier with the Royal Fusiliers, an infantry division attached to the 8th Indian Regiment, and he had been fighting in battles across the world since 1939. Roy had black, slicked-back hair and a slight underbite. Over six feet in height, he also was noticeably tall among the forces in the valley.

Roy was a seasoned fighter, having joined the military as soon as he turned eighteen. In fact, by the time he was fighting at Monte Cassino, he had fought in two wars on three sides. When he was fifteen he dropped out of boarding school to fight in the Spanish Civil War. It was a wrenching ideological conflict for control of the Spanish state, pitting the ultimately successful fascists against united leftists, anarchists, and communists, but Bates’s interests were less political and more visceral. “I fought for both sides,” he said. “I didn’t care, I just wanted to fight.”

That ambition for adventure called again during World War II, though this time Roy had a more vested interest in the conflict, fighting in defense of his beloved England. Roy “was a throwback,” said a friend and colleague named Bob Le-Roi. “He should have been born in the time of the first Queen Elizabeth and sailed with Drake. If ever there was a true buccaneer, it was Roy.”

Winter slowly turned into summer in the Liri Valley, and on a muggy day in May 1944, Roy and his fellow Fusiliers were briefed on an upcoming assault just south of the town of Cassino. He and two other soldiers were carrying supplies for the attack to be launched the next day, in which the Fusiliers would paddle rubber boats across the river and wipe out the German defenses on the other side. Following the briefing, Roy crouched as he ran with his Bren gun to a bank of trees to prepare for the assault. Suddenly, the ground below him erupted in a geyser of fire and dirt. One of the thousands of mines laid by German troops had exploded under foot, sending rock and shrapnel ripping through trees and human flesh. Roy was in and out of 11consciousness, his breathing heavy in his own brain, as he was rushed away from the battlefield by expeditious medics.

Roy missed out on the upcoming assault on account of the explosion, but it turned out to be another battle of indeterminate importance. The Fusiliers had crossed the river but were unable to get much farther, pinned down by machine gun fire until Canadian tanks made their way to the front line and gave the Fusiliers the chance to pull themselves out of their holes. Nevertheless, it burned Roy that he couldn’t be there, and he lay in the field hospital willing his wounds to heal.

Roy recuperated enough to rejoin his men in July, who by that point had excised the Germans from Monte Cassino and were pushing their way further north. Roy had already been stabbed, shot, and crippled by frostbite and disease, and being blown up by a mine was merely an inconvenient setback to the horrendous and wildly exciting duty of being a Royal Fusilier. “I rather enjoyed the war,” Roy was known to say throughout his life, and he always maintained he’d do it all over again as soon as he was called.

Fittingly, this was the man who would go on to found a kingdom in the North Sea and reign for decades as its prince. Roy was indeed a buccaneer from times of yore, and he would put his blood, sweat, tears, and family savings into a singular experiment whose reverberations would endure well into the next century.

BIRTH OF A SCALAWAG

Roy’s preternatural bravery and knack for survival came from tragic circumstances. He was born on August 29, 1921, to Harry and Lilyan Bates in Ealing, west London,† the lone surviving child of six brothers and sisters, who had himself overcome a severe bowel obstruction when he was a baby.

Harry Bates, a butcher, had earned a Military Cross for bravery in World War I and was by many accounts a fairly severe and demanding figure. Lilyan, a nurse during both World Wars, was a force to be 12reckoned with herself. Things could get so volatile that at one point young Roy was accidentally knocked into the fireplace when his parents were fighting, and to toughen Roy up, his father used to draw bathwater in the evening, let it freeze overnight in the unheated bathroom, and then break the ice in the morning and throw Roy in.

The family moved to Southend-on-Sea in Essex when Roy was a few months old because of his father’s lung condition. Harry had been gassed in the war and had difficulty breathing; at one point he had been given no more than a year to live on account of the damage. Southend, built along the north shore of the River Thames where it empties into the North Sea, was popular at the time as a resort city. With its ample seaside air and mud said to contain healing properties, Harry had fond memories of Southend from when he was stationed there during his tenure in the army. (The “on-Sea” suffix was added to many towns in the area to make them more attractive to tourists.)

When Roy was a boy, Southend had become a midsized, bustling city, characterized by winding thoroughfares and residential streets lined with rows of tightly packed townhouses and apartments. With a shopping district and esplanade filled with arcades along the shore, Southend sits atop steep hills that slope down to the Thames, treating residents and visitors to incredible views of the river that seems oceanic in its vastness. Far off in the distance lies the Isle of Sheppey and Kent forms the opposite shore, with numerous islands in between separating the river into channels that flow out to sea. Extending more than a mile into the estuary is the Southend Pier, the longest pleasure pier in the world, which is serviced by its own train.

The Bates family settled into a home in the upscale Thorpe Bay neighborhood in eastern Southend, but imposing trees gave the property a despairing aura. Grim foliage notwithstanding, the climate suited Harry, and he lived very actively until he died at age 79. Meanwhile, Lilyan continued as a practicing nurse well into her late 70s.

Young Roy was a day boy at a boarding school but was not engaged by the experience. He was expelled a few times, though typically allowed to resume his studies at the start of the next term. “It was a quite nice school and they were quite efficient, except what they 13wanted to teach me and what I wanted to learn were quite different,” he said. “The only examination I ever passed in my life was my medical.”

Roy dropped out of boarding school to fight in Spain, and when he was deported back to England, he began apprenticing with 30 other young men as a rancher for Lord Edmund Vestey, whose family owned a meat processing empire that spanned three continents. There was a big map behind Vestey’s desk, and the Lord asked young Roy where he wanted to be stationed. “All the same to me,” Roy said as he pointed to a random area of South America. Vestey told him that was Argentina. “Great,” Roy replied.

Roy’s Argentinean escapade was scrapped when Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939. The chance to travel and fight once again beckoned, so Roy tried to extricate himself from his responsibility to Lord Vestey in order to fight against the Nazis. But the Vestey outfit had already booked him a ticket to Brazil, and, try as he might, Roy couldn’t get himself fired. As a “controlled job,” his was necessary for war production, and his country needed him to tend to his post. So Roy simply stopped going to work, and after sending a series of telegrams trying to persuade him to return, they finally cut him loose.‡

Meanwhile, the military didn’t immediately accept Roy’s enlistment because the war wasn’t projected to last longer than six months. But it quickly became apparent that the world would be mired in another hideous conflict, so Roy was accepted into the Coastal Battalion. To Roy, this was not a suitable option, however, since a home front defense force assignment meant that he wouldn’t be sent overseas for combat. Roy successfully worked his way into the army, where he was put into the Essex Regiment and then commissioned into the Royal Fusiliers.

The British line infantry regiment Roy was assigned to got its start in 1685 as a unit of weapons’ bearers who carried special rifles that could be lit with a less caustic spark, thereby providing cover for the artillery without accidentally blowing up barrels of gunpowder. Since 14that time the Fusiliers had been dispatched to conflicts all over the globe, including the American War of Independence and the slaughterhouse that was World War I’s Battle of Passchendaele. During World War II, they were attached to the 8th Indian Division, fighting in Iraq, Syria, and Iran. In 1943, the 8th Indian Division was moved to Europe, traveling north through Italy, where Roy and his fellow soldiers would engage in the four battles of Monte Cassino. “As fighting men they were of one piece—the warp and woof of an unsurpassed military fabric,” recalled one historian.

Roy was officially discharged in 1946, when he was barely 25, as the only surviving officer from his battalion. He had entered the army as a private but came out as A2 Major—a company commander in charge of up to 200 people. At one point the youngest Major in the British Army, Roy “would’ve gone further up the rank in the war had he not kicked an officer for rebuking him for doing things the way he wanted to do them,” his son Michael later said.

In addition to the numerous injuries he sustained during the war, at one point a German grenade exploded right in front of Roy’s face, shattering his jaw and shredding the skin on his rubicund visage. The damage was so severe that a doctor told him that no woman would ever be able to love him again. A born contrarian, Roy defied the words of the doctor and met Joan, the woman who would be his partner in crime—sometimes literally—for the rest of their lives.

WHEN ROY MET JOAN

As Roy recalled, sometime in late December 1948, he went to the famed Kursaal dancehall on the Southend shore simply “to drink.” There he caught sight of Joan Collins, just eighteen years old at the time. She was laughing with friends and trying to look at Roy without looking at him at the same time. The scene was one of classic romance, where the room darkens, a spotlight shines on two people on opposite sides of the room, and the music becomes fuzzy as they stare at each other through the swaying of an indistinct mass of people. Roy floated across the room, looked at her tenderly, and asked her to dance.

“It was stunning, like what you read in a book,” Joan recalled. “He 15was tall, dark, and handsome. There was no question in my mind that we would always be together from the first minute.”

Joan was a striking woman with a radiant smile and long, blonde hair, her aura shining as brightly as any actress of the time. She did a good bit of modeling, lending her face to a variety of ad campaigns, magazines, and fashion shows organized for charitable purposes. Her modeling career continued throughout the 1970s. In fact, Michael would take his girlfriends to a club in town where a picture of his mother, donning fur, hung in the foyer.

Roy and Joan were seemingly fated to be together. Joan herself was from a military family whose forebears were coalminers from northern England and Ireland. She was born in the Aldershot Barracks on September 2, 1929, to Elizabeth and Albert Collins—a relatively quiet, normal family as compared to Roy’s—but there were some odd coincidences between them. For example, Roy and Joan’s fathers had served together at the Battle of the Somme, both were in the Royal Horse Artillery, both were stationed at the same barracks, and both even had the same toe blown off the same foot.

Joan grew up with her younger brother in Wakering, a small town just east of Southend housing various military installations. Eight years younger than Roy, she was too young to work in munitions factories during the war years, so she took jobs like theater usherette or chocolate biscuit factory employee that were perennially staffed by teens. Joan’s parents sometimes kept her out of school to help around the house, which had water pumps in front and back that straddled the line between the Victorian era and the modern day.

Technically Roy was already engaged when they met (and to Joan’s friend, at that), but it was one of those situations in which the direction he had to take was clear. It took Roy three days to propose, Joan said, “and I thought he was taking a hell of a long time.” The two were married at the Caxton Hall registry office in Westminster in February 1949. They would stay married for more than six decades. “After all these years we never need anyone else around. We’re never bored together,” Joan said later in life. “I met Roy at eighteen and married him after six weeks. I admired him then, and still do.”

Roy initially embarked on the dutiful responsibilities of a husband, 16putting on a tie and commuting to work at a company that imported poultry by the trainload from the Republic of Ireland to the rationed North. “There was rationing in the country then, and I found the only thing that wasn’t rationed that people could really eat plenty of was poultry,” he said. But Roy found that this endeavor came with a lot of dreary deskwork, and he soon had an Office Space moment about the horrors of the nine-to-five.

“I found myself sitting on a train one day at Leigh station and there were five [businessmen] sitting on my side with blue suits and briefcases and bowler hats, and five sitting on the other side,” Roy said. “So I got up at Leigh and threw my bowler hat and my briefcase in the water and phoned up my lawyer and said ‘Get rid of everything. I’m not going to do this any longer.’ And I went and bought a fishing boat.”

While the couple had friends who sailed or fished, neither of the Bateses had any practical experience working in the commercial fishing industry. Fortunately, cheap boats were in ready supply on account of the surplus of vessels built for the war, and the Bateses bought an old military harbor launch that Roy called the Mizzy Gel. The 36-foot boat was previously used to shuttle troops between ship and shore, and the couple outfitted it with other bits of military surplus. B&B Fisheries, the family’s fishing business, would grow to become a decent-sized operation with around a half-dozen boats, but Roy and Joan began looking into additional business options once they discovered that fishing did not bring in significant money. “As they used to say in Leigh, ‘every fisherman’s got his backside hanging out of his trousers,’” Roy said.

In early 1946, the couple set up Airfern, Ltd., a business that would harvest and export “white weed” or “air fern,” a living colony of polyps related to coral that, when taken out of the water and dried, looks like a plant and doesn’t require any water or maintenance. The North Sea is one of the only places in the world where air fern grows in commercial quantities, and Roy got to work learning how to harvest and dry it. He bought one of the very first Scuba outfits and had to spend a week in the Scuba factory undergoing pressure tests to make sure he knew what he was doing. Once he had a handle on diving, he dove down to investigate where the air fern was growing along the 17bottom of the sea. He soon developed a process in which he would dive down and load the air fern onto giant metal rakes being dragged by a retrofitted boat from his fleet. The business was tough to get off the ground, but eventually it flourished, with air fern being sold to fancy florists in New York for use in bouquets and floral arrangements. A horrific flood in 1953 swamped the coastal region, killing dozens of people and wiping out the fern beds, but the business was able to make a comeback, and the family maintained the operation into the 1980s.

Roy was willing to try anything, and his ambition led to increasingly grandiose plans. Later ventures included a chain of butcher shops, a real estate agency, and Decor, Ltd., which imported latex from Malaysia to manufacture swim fins. The only time Joan reportedly put her foot down was when Roy suggested they move to Kenya and buy a farm during the Mau-Mau uprising. “These things attract me like a madman,” Roy admitted. “She puts a little caution into me and makes me think about things. She taught me so much with patience and understanding.”

Besides, there was the family to think about. Penelope “Penny” Bates was born on March 19, 1949, and then came Michael Roy Bates on August 2, 1952. The family moved around Southend, eventually settling into an apartment on the corner of Avenue Road and Avenue Terrace in a Southend suburb called Westcliff, where they inhabited a second-floor apartment reached by ascending a half-walled flight of stairs.

Joan was a devoted mother, taking care of the kids as Roy worked and engaging them in society activities such as horseback riding. Her demeanor contrasted somewhat with Roy’s, who, like his own father, was said to sometimes run the home like it was his army barracks. He expected the same level of old-school toughness out of his children that allowed him to live life on his own terms, and he wasn’t afraid to allow his children to get a little banged up in the process. Michael recalled being thumped by his dad for falling out of a tree instead of successfully climbing it. “It’s difficult to relate to—my father’s reasonably Victorian,” Michael recalled.

But Michael often witnessed his father’s remarkable daring and 18compassion. When he was around ten years old, they were relaxing at the family’s beach hut at Thorpe Bay when Michael heard the cries of two teenage girls who were being pulled out to sea, bobbing up and down in the insurmountable current. Suddenly, Roy sprang into action and ran down the beach, pushing his way through beachgoers, flinging off his sunglasses and sandals, and leaping into the water. Another man followed him, and they dragged the girls ashore. A nurse attempted artificial respiration on the seemingly lifeless girls laid out on the sand to no avail. “Get out of the way!” Roy shouted. He picked up one of girls from behind, pushed his fists into her stomach, and shook her like a ragdoll.

“Unbelievably, what seemed like a gallon of water gushed from her mouth onto the beach,” and the girl began coughing and breathing again. “I have never before or since seen such an unconventional and successful resuscitation,” Michael recalled.

The Bates children were ultimately sent off to separate boarding schools, where Roy’s reputation preceded them. The headmaster of Michael’s school initially wouldn’t accept him as a student because he said he was too old to take on another pupil like Roy. Michael was prone to fighting in the schoolyard, but he eventually settled into a groove in an all-boys school in Wales while Penny was dispatched to an all-girls school. At home on holiday, they were driven to horse-riding lessons in the family Bentley, and the family was by then known as always well-dressed and glamorous.

Even so, the comforts of a prosperous life were not fully satisfying for the Bateses. Though he had forgone the bowler hat and briefcase, Roy—always on the lookout for the next adventure—felt that even his series of unusual yet lucrative pursuits were just another version of the daily grind. Some strange military structures were faintly visible on the horizon from the shores of Essex—ungainly silhouettes just begging to be explored.

*Press accounts of Sealand often refer to Roy as “Paddy Roy Bates.” Paddy was his first name according to his birth certificate but he almost always went by Roy.

†As it would happen, a studio in Ealing produced the 1949 movie Passport to Pimlico, in which the area of Pimlico, London, technically becomes an independent enclave of a French dukedom, thereby separating itself from British jurisdiction.

‡For their part, the Vestey family was enormously wealthy but would later raise some eyebrows for their complex but legal tax avoidance schemes, whose workings one official described as being so hard to understand that it was “like trying to squeeze rice pudding.”

CHAPTER 2

FORT MADNESS

“It was like a watery bus in the sea, stripped of all its fillings.”

—Roy Bates

At 220,000 square miles, the North Sea is a little smaller than France. The funnel-shaped, relatively young body of water stretches from Scotland to Norway and is bound in the east by the shores of Germany, Holland, and Belgium and in the west by Great Britain. Above France it becomes the English Channel, which in turn empties into the Atlantic Ocean. Previously a stretch of earth called Doggerland that connected the British Isles to mainland Europe until about 6500 BCE, the North Sea formed after ice sheets of the most recent ice age melted, isolating what would become the United Kingdom as a series of islands. It is also a fairly shallow—though frigid—sea, only around 300 feet deep on average and just 21 miles wide at its narrowest point between Dover in the UK and Calais in France.

The North Sea region is known for its commercial fishing and oil production industries. It boasts some of the busiest ports in the world, in particular those around the Thames Estuary, around 35 miles east of London. Overlooking that estuary and the river that feeds it, Southend-on-Sea has been an important fishing area for hundreds of years and a nexus of human activity since the first communities were established there around 40,000 years ago. Twice a day, the waters of the Thames recede and leave a mile of mudflats in their wake, stranding boats in the muck until the waters return. Beyond the mud, channels of water flow between the various islands and sandbanks.

The Bates family had their boat the Mizzy Gel docked on the River Roach, around six miles north of their home in Southend. From there they would take it past Foulness Island and up into the River Crouch, 20which in turn flows into the North Sea. Roy sailed for business and pleasure, with his son Michael often accompanying him. As the first generation of the family to make a living from the water, the father and son would sail past docks and container ships and lighthouses on their jaunts to sea, but the huge sea forts peppering the estuary escaped their notice until a fateful day in early 1965.

The fort that would become the Principality of Sealand is an altogether perplexing presence whose use isn’t immediately apparent. Attached to a sturdy concrete base, two immense concrete “legs” rise 60 feet out of the water, with a thin metal platform measuring 120 by 50 feet—about the size of two tennis courts—laid across the top. In the middle of the platform, positioned above the gap between the legs, is the fort’s command center. In its original incarnation, there was another room on top of the first that held radar equipment, giving it a tiered look not unlike a pagoda.

The forts are dwarfed by the humongous container and cruise ships that pass them by, but they seem immense when approached by a small boat. In the same way a building seems to move as you look up from below, so too does the fort seem to “loom drunkenly from the waves.” The structures vibrate deep, unsettling tones when pounded by stormy seas, but on calm days the water gurgles playfully as it sucks and slaps the concrete.

Fortifications have been built along the water at strategic points for over 1,000 years, given the ease of access the Thames gives to mainland England, and they represent the struggles endured by various dynasties and kingdoms. Sturdily built to withstand combat, the Maunsell Naval Forts are named for their designer, Guy Anson Maunsell, a British engineer who is most famous for his unconventional but utilitarian concrete structures. Four of these duoliths were put into place in 1942 to defend the Thames Estuary from Nazi fighters dropping bombs and magnetic mines, since it was said that German pilots didn’t need maps when going on bombing runs to London as they could just follow the river to their target like a highway. The forts—Sunk Head, Tongue Sands, Knock John, and Roughs Tower—were set roughly six miles apart from each other and stretched 26 miles from the north near Clacton-on-Sea in Essex down south to 21Margate in Kent. By the early 1960s, the forts had been left to decay into the sea. The government briefly considered demolishing them or turning them into lighthouses, but ultimately decided that the expense wasn’t worth it.

A GIANT LEAP FOR MICRO-KIND

January 30, 1965, was a day that would change everything—not just for the Bates family but the world map as we know it—as Michael and Roy made their approach to Fort Knock John. Located about three miles out in the Thames Estuary from Southend, it was clear that twenty years of no maintenance had taken its toll. Bits of concrete fell into the sea, and rust was apparent even from far off. Nevertheless, Roy began looking for a way to hoist himself up to the top of the platform to see the fort close up.

The Mizzy Gel did a puttering circle around the legs and stopped near a remarkably dangerous-looking cage that seemed moments away from rusting apart. Maunsell had apparently forgotten to include a way to resupply the fort, and so a scaffolding-like platform was built between the concrete base and the metal platform. A zigzag of ladders led to a small platform under the superstructure, which in turn led to the fort above. Piece by piece it had begun to fall apart over the years, but enough beams and ladders were intact to provide a direct—if hazardous—way of accessing the top. Roy Bates steadied himself on the gunwale of the boat, leapt onto the cage, and shimmied his way up to the underside of the fort. Michael looked up at him, not content to remain on the boat.

Warm currents from the North Atlantic generally keep the North Sea free of ice, but it is a notoriously tempestuous ocean that can make boats bounce “like a champagne cork in a pan of boiling water.” Even Roy second-guessed putting his son up to the treacherous task of jumping from the boat to the cage. But Michael swore he could do it and, swallowing his fear, he leaped to his destiny.

It was one small step for Michael and one giant leap for micro-kind.

Roy stooped under the hatch that led to the deck proper and rammed his shoulder against the door until it finally wrenched loose. He emerged triumphantly into the sunlight. Roy could see for miles 22in every direction, spotting soaring birds, distant boats, and the buildings lining the shore. It was the first time he was able to see the familiar environs from such a unique vantage point. “The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever,” as Jacques Cousteau put it. Twelve-year-old Michael scuttled up the hatch right behind him, practically kissing the deck when he stood on its stable surface. Michael took a few deep breaths, and the pair got to exploring.

The fort was a time capsule full of old machinery beset with rust and the infinite shit of countless birds. The forts were approximately 5,920 square feet—about that of a large house—but the square footage is divvied up among cramped concrete rooms in the towers and the superstructure’s workspaces. The metal superstructure was bisected by a narrow hallway that led to three large rooms on one side and four smaller rooms on the other. The hallway led from the south deck to the north, both of which boasted heavy antiaircraft guns and other pieces of wartime equipment. The walls were big sheets of steel held together with large metal rivets, lending the fort an obvious maritime appearance.

Each leg of the fort was divided into seven floors, the majority of which were located under the water’s surface. Steep, narrow ladders extended down from tiny openings on each floor. The doors seemed to reveal only a depthless, yawning chasm, but beyond the darkness lay the marines’ quarters and storerooms. The fort’s other leg was filled with two 5,000-gallon tanks for fresh water and gigantic pieces of machinery that supplied the fort with electricity and a nominal amount of heat. An elevator in one of the legs had long since fallen apart, leaving a huge shaft that seemed to go straight down to hell. The bottommost floor was about as spooky as could be imagined, and in time the Bateses would find that it served very well as a prison cell.

Michael and Roy walked into what used to be the control room in the middle of the fort. Window coverings were creaked open to let in sunlight, revealing officers’ quarters, workbenches, and ancient privies. There was no human presence, but they felt they were being watched. Cormorants “sat with hunched shoulders and look[ed] at us from under hooded eyes like the boatman from Hades that carried souls across the River Styx,” Michael writes in his autobiography Holding the Fort. 23

All in all, it was a desolate and postapocalyptic environment, and even the entrepreneurial Roy’s first impression was not great. “It was like a watery bus in the sea, stripped of all its fillings,” he said. Nevertheless, the fort held promise, and the trip hadn’t been undertaken for mere curiosity’s sake. Roy could sense the connection between the abandoned sea forts and a roguish new fad sweeping across the UK. He thought deeply about how he was going to claim the territory for himself, like an explorer who had just set foot on a distant land.

THE CONCRETE ATLANTIS

If Roy Bates was Sealand’s founder, then Guy Anson Maunsell was its unwitting architect. It was thanks to the exigencies of global conflict that an idea for mid-ocean forts was taken seriously and would come to make up an unconventional part of England’s seascape.

Maunsell was born in India to British parents in 1884. His father was a strict military man “with little interest in anything other than the men and horses in his command,” but young Guy found himself much more drawn to the challenges of civil engineering than mortal combat. He graduated from university at the top of his class and spent a year traveling and painting before returning in 1908 to work for a construction firm that specialized in concrete. It was a propitious landing, as Maunsell took to the material and would use it in almost all his work.

During World War I, Maunsell worked for the firm that built the largest explosives factory in the world. Maunsell was conscripted into service and served on the front lines before being placed as an engineer in government offices at Westminster, where he was tasked with designing concrete-hulled boats and shipyards. Twelve of the tugs he designed were built, and he designed what is probably one of the most claustrophobic apparatuses ever conceived: a manned concrete fort smaller than a car and tethered to the ocean floor to monitor enemy ships that could be quickly sunk to the bottom of the ocean if spotted. But most importantly, he uncovered plans for a series of seaborne bulwarks developed during previous wars, and these plans would influence the creations for which he is most known.

Concrete forts were a fixture along the British coast, with some of 24Sealand’s forebears standing since the Napoleonic Wars, when the government built almost 150 brick towers up and down the coast from Sussex to Scotland. They were called Martello towers after the region in Spain from which they originated, and many of them are still standing today. Maunsell also found that someone had designed a 10,000-ton structure resembling a giant buoy that was intended to be built onshore and dropped to the ocean floor, with its tower and weapons left sticking far above the waves like a well-armed lighthouse. Because the war was over before full-scale production could begin on the tower project, only two were ever built, one of which was scrapped, and the other of which was turned into a lighthouse.

During World War II, Maunsell worked for the British government in much the same capacity as he did during World War I. He was tasked with coming up with some way to protect the British coastline, particularly the Thames Estuary, which was a vital throughway for supplies. The batteries along the shore and the steamboats outfitted with antiaircraft guns just weren’t cutting it defense-wise, and Maunsell drew inspiration from the earlier towers when considering how to prevent further German raids. He designed an updated version of the mid-ocean tower-fort that employed two concrete pillars instead of one, topped with a metal superstructure that guns could lay across. The towers would also provide the element of surprise to German pilots not expecting gunfire so far from the coast.

According to Maunsell’s designs, the forts would measure 110 feet from the base to the top of the radar apparatuses, with the deck level standing approximately 60 feet above the seabed once sunk, depending on the tides and water depth at the different locations. The pillars initially boasted a blue, black, and gray camouflage intended to help blend the forts in with the horizon while the structures’ odd profiles were meant to be difficult to hit with bombs. At 4,500 tons each, their sturdy construction was meant to withstand significant impact.

Given the profusion of mines dropped into the water and the seriousness of the German attacks—bomb raids necessitated a lights-out policy on shore with the onset of dusk—the idea was to get the fort project up and into production as efficiently as possible. One selling point was the efficient method of construction. The forts were to be 25built in their entirety on huge, hollow pontoons, which would be towed out to sea. Once above the predetermined location, the concrete base would be flooded and sunk so that it came to rest firmly on the ocean floor, with the metal command center and gun decks high above the water. Five-hundred tons of brick rubble would be dumped around the base to keep the Maunsell Forts—built at a cost of £40,000 (around £2,100,000 today)—in place.

But the plan did not catch on with the Admiralty’s top brass. The forts were simply too unusual and were regarded, as Maunsell put it, “as a wild cat scheme.” Maunsell, a “strong character with immense confidence in his own judgment,” was incredibly annoyed by the seeming shortsightedness. As the war raged on, however, the plans for the forts got bumped up to the right person and the project was greenlit in March 1941. Construction began early that summer in the shipyards at Gravesend,* a port city on the Thames a few miles in from the estuary. Huge sections of the shore were dredged to make room for the construction sites. The towers were built by stacking massive reinforced concrete circles called “biscuits” on top of tubular walls, whose rebar insides looked like tremendous cages. Pre-built wooden interiors were lowered into place in the cylindrical towers wholesale, giant rings fit snugly into tubes. Civilians living nearby saw the giant structures taking shape but were in the dark as far as what they were looking at, given the secrecy of the project.

The forts were technically known as “Thames Estuary Special Defense Units” (or TESDUs) and were given the Ministry of Defence code “Uncle,” a number 1 through 4, and the name of the sandbanks on which they were placed. Roughs Tower, which would eventually become the Principality of Sealand, was U1. Knock John, which Michael and Roy explored in 1965, was U4.

Roughs Tower was towed out to sea by three tugs on a frigid February 9, 1942. Moveable objects like tables and chairs were lashed down for the ride. The tower was to be positioned at 51° 53’ 40.8” latitude north, 1° 28’ 56.7” longitude east, the farthest of the 26forts from the coast and technically outside of British territorial waters for the next 45 years. This extraterritorial positioning would prove crucial to the birth of Sealand and its longevity to the present day.

Bad weather caused a delay in sinking the fort, but conditions improved enough that the operation could take place on February 11. At 4:30 p.m., Maunsell himself opened the gates on one end of the pontoon to flood the base of the fort. He noted politely that sinking the forts did not “constitute a definitely controlled operation in the sense that the movement once started can be arrested or altered.” Sure enough, the sinking of Roughs Tower was almost a complete calamity.

A crazy gurgling sounded from underneath the pontoon as the water filled the succession of chambers in the base. One of the stopcocks wasn’t working, so the chambers were filling unevenly. Any weight imbalance from the incoming water could tip the fort onto whatever lay in its path, or at the very least straight into the ocean. Troops were on deck and in the radar station surrounded by sharp-edged objects and extremely heavy pieces of equipment as Roughs Tower leaned at a more and more unsettling angle. They closed their eyes and gritted their teeth, a steady “ohshitohshitohshit” running through their minds, hoping against hope that the engineer’s calculations were correct.

It took an eons-long, white-knuckle 45 seconds for the first pillar to hit the bottom. The troops let out a communal sigh of relief at the resounding thud. The other pillar took only fifteen seconds to sink, putting the fort on an even keel on the bottom and bringing the process to a close.† The mix of concrete and steel in the middle of the sea would later be described as an “industrial-era Stonehenge,” a “Blade Runner-style metallurgical building,” and a “grotesque marine oasis.” 27But in that moment, the fort stood triumphant, as eager and strapping as a fresh-faced recruit to join the fray.

“It was successful,” Maunsell told one reporter laconically.

A WATERY TOMB

A crew of approximately 120 men was stationed on each fort: 90 marines, 30 sailors, and three officers. Forts were linked by a telephone cable that came ashore at Felixstowe, with radar dishes and radar antennae lining the top of the superstructure. Each fort was outfitted with two 94mm Vickers heavy antiaircraft guns and two 40mm Bofors light antiaircraft guns. The Vickers guns were able to fire a 28-pound shell more than 20,600 yards up to 25 times per minute while the smaller Bofors guns could fire a two-pound shell more than 10,800 yards. Numerous other small machine guns were aboard the fort, and the troops were even given lances with sharpened hooks to fend off any invaders.

A Navy grunt could be expected to be on the fort for around six weeks at a stretch, after which they were given ten days leave and three days of duty at the base on the shore. The officers lived in relative comfort in the top floors of the towers, but the crew, who slept below the surface of the water, had inadequate light and heating. The lapping of the waves on the sides of the pillars could be soporific, but, as journalist Simon Sellars recently recalled, the sensation was also like sleeping in an underwater tomb.

“The room has no windows. It is dank, pitch-black, and deathly still. I’ve lost all spatial coordinates,” Sellars wrote. “I hear a distant, dull hissing, like soil leaking through a coffin lid…I fall asleep, letting the blackness suffocate me. The dark is so heavy, it’s like I’m buried alive.” So unusual is the feeling that one of the caretakers on Sealand said he was surprised when Sellars didn’t wake up screaming.

Living on the fort did in fact provoke psychological issues in many of the marines, manifesting itself in a condition called “fort madness.” Recruits were required to take up knitting, painting, model building, egg decorating, or any other activity they could to keep their minds occupied. Marines were reportedly not allowed on leave until they showed the fruits of their labor, and the best project was awarded a 28carton of cigarettes. Nevertheless, a medical orderly stationed on the fort reported troops often coming to him in tears. At least one soldier jumped to his death in despair, preferring to drown in the North Sea than stay another moment on the fort. Eerily enough, he took his cigarettes with him over the edge but left his clothes folded neatly on his bunk.

“The story I heard, the guys that were actually out here were people that had been on shore-based gun emplacements and disappeared with the local girls and got drunk and God knows what else, and so they sent them out here as punishment,” said Sealand’s longtime caretaker Mike Barrington, whose association with the Bates family goes back more than 30 years. “It’s like Alcatraz—there’s no escape. Aside from jumping over the side, but you’ll break your neck when you hit the water and end up somewhere in France or something if you’re lucky.”

The vulnerability to attack could be maddening as well. At one point a magnetic mine was floating on the surface of the water toward the fort. Marines began shooting at it trying to blow it up, but the mine remained unharmed as it floated closer and closer. The men all plugged their ears and braced themselves for the blast, but miraculously, it passed under the tower without exploding, and a nearby ship eventually blew it up after making fun of the people on the fort for being such bad shots.

The four naval forts weren’t the only unusual Maunsell structures off the coast of England. He also designed eleven-by-eleven-square-meter buildings that sat atop four narrow concrete legs for the army. Seven of these structures together comprised one complete fort, with catwalks connecting the individual units. The control tower with radar equipment at the center of the arrangement was surrounded by towers full of antiaircraft guns and powerful spotlights. The army forts were placed in the Mersey Estuary, and three more were built in the Thames in 1943. The towers took eight weeks to build on the pontoons but were battle-ready in the middle of the ocean in less than eight hours. Interestingly, the closest fort to the Bates family home is one of the army forts, and to this day it can be seen with the naked eye on a clear day from the shores of Southend.

Both sets of Maunsell’s forts did their duty throughout the war, blasting away at incoming German planes and watching them crash 29and explode in the water miles away. By the time the forts were all up and running, blitzkrieg-style air raids were on the decline, though, as the Germans concentrated their diminished airpower elsewhere in Europe. The forts were ultimately responsible for the destruction of 22 planes, one German submarine, and 33 “Doodlebugs”—jet-powered missiles that presaged the ballistic missiles used in later wars. The number was not tremendous, but the men were always happy to paint another swastika on the tower to celebrate the planes they shot down. The forts are credited with greatly reducing the number of mines dropped into the estuary, thereby facilitating the vital movement of people and supplies.‡

The British government left the forts to the elements following the end of the war. Some remained occupied by a bare-bones crew, but by 1958 the forts were abandoned completely. A few of the forts were used intermittently for British military training exercises, and in 1968 the “Fury from the Deep” episode of Doctor Who was filmed at the Red Sands army fort.

Maunsell once said the forts were designed to last 200 years, but some didn’t fare that well. On March 1, 1953, a Swedish freighter called the Baalbek crashed into the Nore Army Forts, in the Thames Estuary between the Isle of Sheppey and Southend-on-Sea, during a heavy bout of fog. Two of the forts were destroyed, and four of the forts’ maintenance crew died in the collision.§ The Nore towers were removed and scrapped in 1959. Other forts were built on a shifting sandbar that eventually pulled them into the sea.

30As for the naval forts, Tongue Sands became unstable because it hadn’t settled properly. In 1947 it had started shaking and falling apart, and the crew had to be rescued. Not long after, one of the fort’s legs was severely damaged in a storm, and the fort started leaning fifteen degrees. An intense storm broke the rest of Tongue Sands apart in 1996 and left only a macabre eighteen-foot stump of the southern leg. Knock John Fort is broken but still standing, while Sunk Head was eventually blown up to teach Sealand a lesson (see Chapter 5). Roughs Tower, the bastion of power that it is, was resurrected as Sealand in 1967 and appears to be in good health into the present day.

Maunsell is known in industry circles for his other contributions to the war effort and for his “undeviating professional integrity.” He was said to be a parsimonious boss who paid his employees less than scale, as well as a family man who based his family vacations around trips to inspect engineering projects, but G. Maunsell & Partners, the firm he founded following World War II, would come to be known for its economical but quality engineers and methods of construction. Many of Maunsell’s extant projects are remembered today for their functional designs, such as bridges in Australia and Denmark that are known among engineering enthusiasts to be modern classics.¶ G. Maunsell & Partners merged with the engineering consultant firm Oscar Faber in 2001, becoming Faber Maunsell, and then with global engineering firm AECOM in 2002. The group officially changed its name to AECOM in 2009.

“Engineers have always been society’s unsung heroes yet they have played a pivotal role in the success of civilization,” Maunsell biographers Frank Turner and Nigel Watson write. In Maunsell’s case, he played a pivotal role not only in safeguarding England from invading fascists but also in the development of a new, unorthodox type of statehood.

31ON THE WAY back from Knock John in January 1965, Roy felt a kinship with the old structure, as both had served king and country with pride and aplomb. As it would turn out, in just over two short years, Roy would be king of his own country. Until then, however, he was going to don a different crown. The 1960s brought an endearing kind of piracy to Britain’s shores, and from atop the glorious heights of Knock John, Roy Bates was going to hoist a Jolly Roger of his own.

*