11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Vertebrate Digital

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

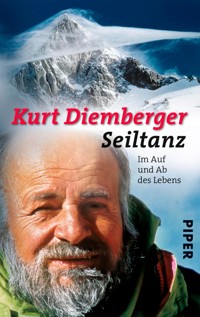

Kurt Diemberger belongs to an elite mountaineering club. He is one of only two climbers to have made first ascents of two 8,000-metre peaks - Broad Peak and Dhaulagiri. His Broad Peak ascent was the first eight-thousander climbed in alpine style without oxygen. He had climbed the major Alps north faces (the Eiger, Matterhorn and Grandes Jorasses) by 1958 and was awarded the fifth Piolets d'Or lifetime achievement award. But Diemberger's adventures revolve around more than climbing, as Spirits of the Air reveals. Of course, there is plenty of mountaineering - expeditions to Makalu and Everest, America and the Hindu Kush. But there are also rickety aeroplanes which inevitably crash, anacondas to wrestle and bar-room meetings with Reinhold Messner. And there is Diemberger's filmmaking. A pioneering filmmaker, he has shot on the top of Everest and in the Arctic circle, making several mountaineering film firsts and becoming one of the best cameramen of the genre. In Spirits of the Air Diemberger describes his life and adventures after the 1986 K2 disaster, which affected him greatly, and some earlier episodes. He reflects on the contrasts between his life in Europe and the always-beckoning Himalaya, and on family, loves and friendships. Describing his experiences with a tremendous zest for life that is both endearing and compelling, Diemberger creates a very readable and very different mountaineering autobiography.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Spirits of the Air

Spirits of the Air

Kurt Diemberger

Translated by Audrey Salkeld

www.v-publishing.co.uk

To my father

Only the Spirits of the Air know What awaits me behind the mountains But still I go on with my dogs,Onwards and on ...

This old Eskimo proverb defines my existence – and not only when I am in Greenland. I have been called ‘the Nomad of the Great Heights’ – certainly ever since I clambered to my first summit as a crystal-hunting boy, since I set out on my grandfather’s bicycle with two friends to reach and climb the legendary Matterhorn, I have felt urged beyond the horizon in search of the unknown.

And that haven of peace behind the last mountain? Does such a thing exist? There is always a new enigma springing up to meet you. Some new secret. That never changes. However far you travel …

Only the Spirits of the Air know what lies in store for you, says the Eskimo on his dog sledge.

That is Life.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Kurt Diemberger

PART 1

I Can Never Give Up the Mountains

Spirits of the Air

The Second Birthday

Double Solo on Zebru

Crystals from Mont Blanc

I Win a Car

As a Mountain Guide

PART 2

The Magic Carpet

How I got involved with Filming

Blind Man’s Buff

Friendly Margherita

Our Brush with an Anaconda

Montserrat

On the Puddingstone with Jordi Pons and Jose Manuel Anglada

PART 3

Hindu Kush – Two Men and Nineteen Camps

The Tactics of a Mini Expedition

Nudging Alpine-Style a Step Further

An Expedition Journal

Two Chickens Come Home to Roost

Neck and Neck with Reinhold

The Third Eight Thousander?

Climbing the 8,000-metre Peaks

PART 4

In the Eternal Ice

On the Trail of Alfred Wegener

Who was Alfred Wegener?

A Green Land?

Origins of an Expedition

The Voyage to Greenland

‘Modern Times’ in Umanak and Uvkusigsat

The Difficult Landing

Dogs? Propeller Sledges? Horses?

Ascent to the Inland Ice

First Finds

1930: Towards Station Eismitte

The Sledge Journeys

The Propeller Sledge Fiasco

Nunatak Scheideck, a Treasure Trove!

Alfred Wegener’s Last Journey

Qioqe, Agpatat and – the Final Take

PART 5

A Night on Stromboli

… and Everyday Life in Italy

‘I Canali’ – the Channels

The Millipede

PART 6

A New World

Impressions Gained During an Extended North American Lecture Tour, and its Aftermath

How to Catch a Millionaire

Milestones in California

Fifty-six Steps Around a General

Grand Canyon – A Sunken World

Atlanta – The Holy City

The Lake

In the Plane

A Goddess of Nature

The Wizard – Climbing the Needles of Sierra Nevada

On the Gulf

PART 7

Makalu (8,481 metres) – The Turning Point

Yang Lhe – The Enchanted Forest

Through East Nepal

Strikes – Left With Nine Out of a Hundred

Chance and Mischance With the Oxygen – My Friends’ Summit

Makalu … With a Monkey Wrench

Depot Kurt

‘Take One’

On the Summit of Everest

Death Valley in Winter

PART 8

Hildegard Peak (6,189 metres) – Island Peak

The Green Flash

Gasherbrum II

Spirits of the Air

A New Horizon

Under the Spell of the Shaksgam

APPENDICES

A Chronology of Main Climbs and Expeditions

A Note on Terminology

A Selected Bibliography

Note on Heights

Photographs

Acknowledgements

Unless otherwise specified the illustrations are from the Kurt Diemberger archive: for collaboration in some cases I want to thank my companions named in the book. Professor Karl Weiken’s historical pictures of the Alfred Wegener expedition were a great help and a notable contribution. Other photographs came from Robert Kreuzinger, Sadamasa Takahashi, Doug Scott and Hermann Warth.

Most of my photographs were taken with a Leica R3 or SL2.

Credits for the sketch maps are given, but I want to thank my son Igor and my daughter Karen for helping in their adaptation for Spirits of the Air.

A special thanks goes to my father for historical work in the Greenland chapter and to Professor Karl Weiken for checking my text and lending expedition reports. I am also very grateful to Axel Thorer for the permission to print his humorous story describing the atmosphere in a hotel bar in Kathmandu which appeared in May 1980 in the German edition of Penthouse.

Last but not least, I would like to thank Audrey Salkeld for her translation and Maggie Body, my editor.

Kurt Diemberger

Bologna, 2015

Kurt Diemberger

Austrian mountaineer Kurt Diemberger one of an extremely select club – he is the only climber alive to have made the first ascent of two of the world’s 8,000-metre peaks: Broad Peak in 1957 and Dhaulagiri in 1960. An accomplished writer and filmmaker, he became one of the top high-altitude filmmakers in the world and his books have enjoyed popularity around the globe. He is now recognised as one of the finest chroniclers of the contemporary mountain scene, with his writing guaranteed to enlighten, move and entertain. In 2013, Diemberger was awarded the fifth Piolets d’Or lifetime achievement award.

Born in 1932, Diemberger began mountaineering in the Alps, quickly notching up an impressive list of ascents. By 1958 he had climbed the three great north faces of the Alps – the Eiger, Matterhorn, and Grandes Jorasses. He soon turned his attention to the Greater Ranges, where he made several notable and first ascents, usually without oxygen.

Both of his 8,000-metre first ascents were made without additional oxygen and Broad Peak, which he climbed with Hermann Buhl, Marcus Schmuck and Fritz Wintersteller, was the first eight-thousander to be ascended in alpine-style, renouncing help from high-altitude porters and artificial oxygen and without backup from base camp) long before this technique became widely used on the Himalayan giants. In all, Kurt has climbed six of the eight-thousanders, and Broad Peak twice (the second time in 1984 with Julie Tullis, twenty-seven years after his first ascent).

Diemberger’s mountain film career began in 1958, when he filmed the greatest ridge-traverse of the Alps – the ‘Peuterey Integral’ on Mont Blanc, including the Aiguille Noire and Aiguille Blanche – from a rope of just two (his patient partner during the five-day climb was Frans Lindner).

He then filmed the first ascent of Dhaulagiri in 1960, made films in Greenland, the Hindu Kush and in Africa, and in 1974 took his sixteen-millimetre camera up the ‘traverse of the future’ on Everest when he reached the top of Shartse (7,500 metres), having made the first ascent with his friend Hermann Warth – leaving the continuation of the enormous ridge traverse via Lhotse and Everest for others still to come.

Later, in autumn 1978, Diemberger succeeded in making a sync-sound film on the top of Everest itself, recording his French companions and making a complete 360-degree panorama with his still camera. It was a world-first and, for Kurt, a keen photographer from his earliest visits to the Alps, a ‘crowning moment’.

Diemberger made several award-winning documentaries with Julie Tullis, his high-altitude filming companion and ‘other ego’ in later years. These included three films on K2, where the pair also entered the field of documentaries of local people in the Himalaya with ‘Tashigang – a Tibetan village between the world of humans and the world of spirits and mountain gods’.

Both had great ideas for filming in this area, and they would have continued their creative union but Julie, after reaching the summit of their dream mountain K2, died in a long-lasting blizzard during the notorious ‘black summer’ of 1986, which claimed the lives of thirteen climbers on K2.

In the Shaksgam wilderness, behind K2, a drum full of gear has been hidden since 1999 and Kurt, after seven previous visits, hopes to return for future exploration. When he was awarded the Piolet d’Or for lifetime achievement in 2013, it was not just for having climbed so many north faces, or having overcome the Giant Meringue of the Koenigsspitze (then far ahead of similar ‘stunts’), but for what he had created during his mountaineering careers for all others with his camera, images and writing.

— PART 1 —

I Can Never Give Up the Mountains

We are climbing up Nanga Parbat, my daughter Hildegard and I, entering the Great Couloir of the Diamir face. Behind us rear the wild summits of the Mazeno ridge, a fiercely serrated wing of blue ice and steep rock jutting from high on the main body of the mighty mountain. Way below glints the green of the Diamir valley.

Here, all is steepness and shadow. We keep plunging our axes into the snow, and of course, we are wearing our crampons. Hildegard – blonde, twenty-five years old – is a confident climber, even if, as an ethnologist, her deeper interest lies with the people of the mountains. She has come with me this time to the peak that was Hermann Buhl’s dream – and, who knows, the two of us may reach as far as 6,000 metres. Perhaps, in a few days, I might even go to 7,000 metres, but I am not pinning my hopes any higher. I have no idea how my K2 frostbite will bear up at altitude. It was only just before Christmas that I had the amputations to my right hand – and with my damaged toes I cannot entertain any hopes of the summit. Yet neither can I accept the prospect of staying down. There is no way I can give up climbing mountains.

Below us, on the slope, Benoît has just come into view, the young French speed-climber attached to our expedition … tack, tack, tack, tack … his movements are like clockwork, as is the rhythmic throb of his front-points and his axe in the steep ice of the couloir. He wants to climb the 8,125 metres of Nanga Parbat in a single day. But not today – today he is only practising.

Quickly he draws nearer.

‘Who goes slowly, goes well – who goes well, goes far … ’ Whatever became of that old proverb? The wisdom of the old mountain guides, it seems, is now out of date. Tack, tack – tack, tack, tack, tack – tack, tack … Benoît is a nice guy and has remained refreshingly modest, despite his prodigious skills; he is small, fine-boned, gentle. I like him, even if some of his opinions send shivers down my spine. Others I have reluctantly to accept (not wanting to start any arguments up here! But what is the point in all this running? What good are records up here?). It must make some sort of sense to him.

Here he is! Benoît Chamoux. The speed artist, the phenomenon! He pants a little, greets us, laughing, and we exchange news; then I fish in my rucksack for the sixteen-millimetre camera. My job is filming, but it’s my pleasure, too. Showing other people what the world is like up here … that is part of what mountaineering means for me. Not this alone, of course …

Still, I want to bring down truth, not fiction! And if, for some bright spark, happiness is running up mountains – then he, too, is part of this world of Nanga Parbat. (My daughter, I must say, has thought so for quite some while – perhaps that’s an ethnological observation?)

I film the young sprinter: well, it looks fantastic, I think, eye to the viewfinder, the way that guy comes up! So I have him do it three times more, up and back again – the way film-makers do, and he is in training, after all.

Before I can dream up further variations, big clouds start rolling in. A change in the weather? Nothing unusual for Nanga Parbat. We descend.

Base Camp, down where it’s green …

Only the Spirits of the Air know how this will turn out for me. I contemplate my discoloured toes – all red and blue – as I swish them round in a bowl of water. Our cook, the good Ali, has tipped at least half a kilo of salt into the water, anxious to do what is best for me. How long will it take till I am fit again? Months, or years?

This is not the first time I have felt all is nearly over, that I am stretching life thinly: coming down from Chogolisa after Hermann’s death, or during the emergency landing I made with Charlie – what I call our ‘second birthday’. But this time? This time it is different.

Do I still enjoy climbing? It can never be as it was before.

And I will never come to terms with what happened on K2. Up on our dream mountain I lost Julie, lost my climbing companion of so many years, sharer of storms and tempests, joys and hopes on the highest mountains of the world. How often did we count the stars together, or look for faces in the clouds?

And then, suddenly …

So many people died on K2 that summer. Julie and I had been in such fine form, we were perfectly acclimatised – we ought not to have lost a single day! But I’ve no wish to set off that spinning wheel of thoughts again … It’s over. Nothing can be changed. The dream summit was ours – and then came the end.

Life, somehow, goes on. The mountains, like dear friends, have always helped me before. Whenever it was possible. Where is the way forward now?

Agostino da Polenza, our expedition leader on K2, was here at Base Camp until a few days ago. Then he dashed off to get another project under way, one on which I am again to be cameraman: re-measuring Everest and K2 for the Italian Consortium of Research (CNR) – or, more accurately, for Ardito Desio, the remarkable ninety-year-old professor who, as long ago as 1929, pushed into the secret valley of the Shaksgam beyond the 8,000-metre Karakorum peaks till he was stopped by the myriad ice towers of the Kyagar glacier. Yes, it’s true, the secrets are not only to be found on the summits …

They wait also behind the mountains. And I think of years that have long past, adventures in the jungle, in Greenland, but in more ‘developed’ areas, too, places like Canada; or the Grand Canyon with its rocky scenery – where time is turned into stone. I remember Death Valley. And expeditions to the Hindu Kush … that first glimpse into hidden corners of the glacier … the first circuit of Tirich Mir.

There was an eighteen-year gap between my second 8,000 metre peak and my third. But I have no regrets about that: it was time well spent. Many chapters of this book bear witness to that.

‘Guarda lassu – there they are!’ Hildegard turns her head excitedly from the camera tripod, swinging her long blonde hair, ‘Look!’ She points up at Nanga Parbat, which even from this distance fills the sky above the treetops. ‘They’re almost up!’ Her eyes are shining. We are in a small summer village in the Diamir valley, surrounded by cattle-sheds, herdsmen, women, many children … and goats, goats and more goats: two or three hundred of them! You can scarcely hear yourself speak over the sound of bleating. There are millions of flies, too, but they do not seem to bother Hildegard. I flick them irritably from my forehead and press my left eye to the viewfinder to peer through the 1,200-millimetre lens: yes, I see them! Three tiny dots, and a fourth one, lower down, right in the middle of the steep summit trapezium. They are going to make it!

We are beside ourselves with joy. Those lucky sods – lucky mushrooms, as we say in Austria – just the right day they’ve picked for it! And I feel a twinge of sadness not to be up there with them. But not for long: as we watch our companions inch higher, happiness suffuses every other feeling. But one dot is missing up there. It worries us at first, then we tell ourselves it must be Benoît. He will not have left Base until the others reached their high camp.

He is bound to catch up with them before long!

Then the clouds swallow everything.

We scoop up our belongings and hurry away, anxious to get to Base Camp before the others come down; we want to prepare a welcome-home party, a summit feast.

Two days later: they are all down. Soro, Gianni and Tullio all made it to the summit – shortly after the clouds cut them from our view. Only Giovanna, the lowest dot, turned back before then. And Benoît? He had a real epic up there …

At first all went well. He reached the summit as planned in a single day from Base Camp. (Normally – if you can speak of normality in terms of Nanga Parbat – it takes at least three days for an ascent.) But then began a chain of misfortune: during the descent, Benoît was overtaken by darkness and lost his way in the giant Bazhin basin. All night long he wandered backwards and forwards up there at around 7,000 metres because, with his lightweight equipment, he dared not sit down for a bivouac. He did not discover his companions’ final camp until morning …

Benoît looked thin and drawn, almost transparent, as he staggered finally into Base … but an incredible willpower still burned in his eyes. We flung our arms round him, so happy to have him back.

***

The sun is shining, its light reflecting off the small stream which runs across the sloping meadow on which our base camp stands. A good place: protected by a moraine bank from the air blast of the many enormous avalanches which thunder down from the upper slopes and teetering ice balconies of Nanga Parbat and the Mazeno peaks. Here, at 4,500 metres, frost binds our little brook every night, covering it with an embroidery of wonderful ice crystals. But in the morning, when the sun appears behind the inky blue bulk of the mountain, it flashes and sparkles everywhere and, as the crystals and plates of ice crackle and split, gradually the murmur of the little stream starts up again between the tents. Gianni and Tullio, inseparable as ever, stroll across the grass and kneel on its bank, dipping their hands in the icy water and splashing it over their faces … they chatter and laugh; Soro and Giovanna stretch out in the sunshine; Hildegard, lost in thought, wanders over the moraine, and Benoît sleeps, and sleeps, and sleeps. He has earned it. The good Ali prepares breakfast, and Shah Jehan, our liaison officer, squints lazily into the sun above his enormous beard and tells again of all the ibex he has bagged in the Karakorum. This is the man we know could never hurt a fly. In the summer of 1982, on my first expedition here, I climbed with him to 6,500 metres on the Diamir face. Next time – 1985 – he was unfortunately not with us. That was when Julie and I went to 7,600 metres: only another 500 metres or so would have seen us on top, but when we came to make our final attempt the weather turned against us …

I am looking up at the dark blue trapezium, in shadow now: some day I’d love to go up there. It will have to wait till I’m better, and that could be years yet. But look, there it is, the summit that Julie and I were so close to.

Will I get another crack at it?

Will I ever stand on the top?

And, if I do, will I come down again – or stay up there for ever?

Even if I never make it up there, I have to have the experience again, this moving up between the clouds …

Once you have started that …

‘I climb mountains for such moments,’ Julie had said, ‘not just to reach the top – that is a bonus!’

I will go up again.

Then my thoughts turn to Makalu.

Many years ago that was, when I faced the question of whether or not to make one last try – knowing that, on whatever I should choose, would depend my whole future.

Spirits of the Air

Strange eddies of cloud spill over the summit of Mount Everest, twisting veils, transparent fans, mysterious phantoms. Catching the light, they shimmer in all the colours of the rainbow – deep purple, radiant green, yellow, orange – a swiftly changing kaleidoscope.

Does it herald a storm?

As I watch, some of the clouds take on a mother-of-pearl lustre, others drain of all colour. It is a strange cavalry, galloping, multiplying, gradually filling the whole sky. The red granite summit of Makalu, just over 3,000 metres above me, wears a wide-brimmed hat, like a gleaming fish. I have often seen such clouds in the Alps, on Mont Blanc, and again I’m prompted to wonder if a storm is on the way. Down here in Base Camp the air remains very still, with only an occasional limp flutter from Ang Chappal’s prayer flags. He hung up two strings of them when we first arrived to keep favour with the mountain gods and spirits. I look beyond them and out over the stone cairn on its little hill to the side of camp: what should I do? Should I attempt Makalu? What hope have I got of reaching the summit? It is eighteen years since I last climbed an eight-thousander.

The prayer flags stir weakly, while high above, the wild clouds charge in every direction. The rainbow colours have disappeared, but light and shadow animate the spectacle. The sun – one minute a fiery ball, the next a pale disc – sinks slowly towards the ridge of Baruntse, the great seven-thousander on the far side of the valley. Down here it is still warm, even though we are above 5,400 metres.

So what’s it to be? Shall I give it a try, make a start?

Not today, certainly. But soon I have to come to a decision; we have already ordered porters for our return march. On the other side of the campsite Hans and Karl are sprawled on the ground. They staggered into camp two days ago with Hermann and the Sherpas, completely whacked after an incredibly painful descent from the mountain. They were changed men. Hans, who is usually so cheerful, wore a bleak, dead look behind his double goggles.

‘I wish you luck for the top, Kurt,’ he said gruffly, in a voice barely above a whisper, ‘but no bivouac!’

All the toes on one of his feet are frostbitten, and Karl is in almost as bad a way. He can scarcely hobble, or even accept support from his friends because four of the fingertips on his left hand are blackened as well. He muttered something, too, but I can’t now remember what it was. Those must have been horrific days, coming down from their bivouac at 8,250 metres, step by painful step, down through four high camps. Later, helping Karli with his bandages and medicines, I asked him whether the top had been worth all the anguish. He was silent for a while, then said, ‘Oh, yes, it was worth it … ’ and, indicating his swollen foot with a bitter smile, the old Karli-smile, added, ‘We’ve got this under control now, haven’t we?’ Certainly, it won’t be long till the porters come, but Hans and Karl are in for a miserable journey back.

If I do still want to go for the summit, I dare not delay any longer. I should start tomorrow, or the day after at the latest. I sink back into the soft sand near our tents and gaze up at the chasing clouds. How many men, like me, have wondered what their tomorrow would bring, and known that on the decision of the moment, all the rest of their lives depended? Perhaps they have known that the decision could be avoided – perhaps they did sidestep it, but what is that for a solution? You never know what you’ll encounter tomorrow. Only the Spirits of the Air know that … So what’s to do? Looking up, I ponder that age-old question, and it is as if, while I am losing myself in the whirling clouds, an answer gradually reveals itself: an answer not in words, but in certainty. And I continue gazing at the weaving veils, follow their courses, their variations, while all questions dissolve away. I can feel the motion of the wheeling shapes, and if I surrender to it, I am no longer here, but there …

The Spirits of the Air: with what power they rise from nothing, secretively, and as quickly vanish once more. Rolling mists, tumbling cascades, weightlessly dancing on their way, multiplying as they go into strange new figures that reach out to embrace each other with their fluttering arms, sometimes succeeding in bringing an evanescent new creature into existence, but mostly melting away before they can touch. Spirits of the Air? Can they really know what tomorrow will bring? Where do they hide when the air is cold and clear, and when in the icy stillness mountains stand like blue crystal in the morning sun, when a pale full moon floats in the daylight sky until, sapped of all strength, it sinks to a mountain ridge and you imagine it rolling, like a barrel, down the hill.

Are they behind the mountains then? Somewhere they must be continuing their ballade. Where is certainty? The secrets are on the summit and beyond. ‘Only the Spirits of the Air know what awaits me behind the mountains.’ So runs the old Eskimo proverb. ‘But I go on with my dogs, onward and on.’ Some days ago, when I was lying sick, down below in the rainforest, I fully believed there was no future for me on big mountains, that my fate lay away from them, somewhere behind.

But now I know: it is up there, on the summit of Makalu. If I don’t try this climb, I have no future. And if nobody wants to come with me, then I shall have to go alone. Sometimes there is no way forward for a man if he does not find the answer to his question.

The Spirits of the Air told me: Go up!

The Second Birthday

Whatever happens to me now is a bonus. By any normal standards my life should have ended several years ago ... it all came about innocently enough.

‘Charlie’s bought an aeroplane!’ – the news went round like wildfire.

How come so fast?

Never imagine climbers to be strong, silent types, not given to chatter! Nothing could be further from the truth. The discussion over the placing of a single piton can rage for hours. And if, in putting up some great new route, a climber strays beyond the iron disciplines of the purists (let alone, he may not have done it at all) then the talk spreads faster than bush telegraph. Usually the sole topic is mountains but this news about Charlie was something extraordinary. It was common knowledge that he had started out as a modest ski instructor, then for some years shuttled between America, Australia and Europe before opening a small sports shop in Innsbruck. Nothing extraordinary. But now, all of a sudden, Charlie has surprised everyone.

‘Hey, guys, heard the latest? Charlie’s got himself wings!’ Brandler tells Raditschnig, Nairz passes the word to Messner, Stitzinger phones up Sturm ... Where did he get that kind of money? Does he know how to fly the thing? How long before he breaks his neck? These were the questions doing the rounds. But sooner or later almost everyone looked forward to a joyride. Only the more cautious of us preferred to wait and see. As one of Charlie’s oldest friends, I knew some of the facts: one, that the machine was a single-engined Cessna 150; also that Charlie was not his real name. He had been born Karl Schönthaler, and cannot abide his nickname. Nevertheless, ‘Charlie from Innsbruck’ is how everyone knows him, and if I refer to him differently, nobody will know who I’m talking about. Aeroplanes are easier: they have an identification number, and all those with the same number are similar. Charlie’s, however, must have been something of a one-off, but I don’t want to anticipate ... He was delighted with it. At first.

‘Fancy seeing you!’ Charlie greets me on the fateful day, his blue eyes crinkled with pleasure. ‘Hey, remember our Piz Roseg climb?’ he says, ‘I went and took a look at it the other day.’ Easy for him, I think. Just a hop, here, there, wherever he wants …

‘Come on, let’s go there now, why don’t we?’ He pushes back his ski cap rakishly, and throws me a challenging look. The old devil doesn’t change! Should I take up his offer? I am cautious by nature, but he has been flying for a year now, and I have always had complete faith in him as a mountaineer. I convince myself I trust him just as implicitly as a pilot ... and that is how I come to be standing on Innsbruck airfield shortly afterwards, while Charlie squints up at a clear, blue sky. ‘Okay,’ He smiles, content. ‘Let’s go! Let’s spin over to the Bernina and say hello to that route of ours.’ [1] Seeing your old first ascents again is fun, especially from the air; you can congratulate yourself on how great you used to be. (Mountaineers are no less vain than anyone else – and certainly, we two are no exceptions.) Again, he says it, this time more solemnly: ‘Come on then, back to the scene of our triumph,’ and slipping on his gloves, he caresses the shining aircraft, at the same time casting me a stern glance. ‘Flying is a serious business, Kurt,’ he warns. ‘You are not to make me nervous. No taking photographs the whole time and, Kruiztuifl! above all, don’t bother me with a string of questions … ’

Charlie comes from the South Tyrol. He has this habit of lapsing into dialect at moments of great importance or stress. ‘It’s all right,’ I try to calm him. ‘I’ll only take pictures from my side of the plane,’ and I hug my two cameras to my chest. (The reader should know that many pilots have this obsessive fear of photographers getting in the way of the controls, besides wanting to know the name of every last garden shed on the ground. A flying doctor friend in Italy would grow very nervous when I used to persuade him to open the door for a better view of the fields and villages.) But if Charlie is worrying that I might block his view, at least he’s keeping his eyes open, I think, not pinning all his hopes on his instruments.

That turns out to be true. As we take off, my friend continues his lecture: ‘It’s more important for me to catch a glimpse of the mountain, than that you get it in your viewfinder … ’ Okay, Charlie. I take the point.

We are already passing the crags of the Innsbrucker Nordkette – on my side, luckily. Charlie is whistling cheerfully, and seems utterly at peace with the world (with me, too). As he gently runs his snow-white gloves over the gleaming fittings of his beloved plane, I think how well he has done for himself. How good to have such friends! Who work so hard. Ski instructor to aeroplane proprietor – whoever would have thought it? But Charlie has always been one of those silent, unexpected geniuses.

I aim my tele-lens down into the Inn valley to capture a neat village – or small town – for my picture archive. ‘Where’s that, Charlie?’ I ask, since a photograph isn’t much good without a caption (publishers don’t take kindly to invention … )

‘There you go – at it already,’ he answers with irritation. ‘I don’t know what it is. Isn’t it enough that we’re airborne, who cares what the village is called?’ And he snorts, ‘It’s not a village, anyway – that’s a town. Telfs, probably. Yes, it’s Telfs!’

Don’t ask a pilot about geography, I think to myself. (It comes as a surprise to learn that pilots don’t always know exactly where they are. My Italian doctor friend once circled with me above the small town of ‘Stradella’. Wasn’t it curious, I ventured, how similar the big golden Madonna on the church tower was to the one in Tortona – which, as it turned out, was where we were. Clearly, my friend didn’t open the door often enough!) It seems to me pilots are so busy taking care not to bump into another aircraft – that they are happy to just watch the ground go by, knowing only vaguely where they are.

Now, on Charlie’s side, a wild valley appears, hemmed in by high peaks – even today, I am not sure if it was the Kaunertal or the Ötztal, everything looks so different from the air; Charlie will not commit himself beyond saying it is the Ötztal Alps. Not to worry, I tell myself, we should soon see the Wildspitze – and then we’ll know where we are. The distinctive three-thousander is the highest mountain for miles around. Charlie confirms the Wildspitze will be coming up shortly, and I cannot resist a mock-polite cough. He glowers in my direction, remarking huffily that the main thing is not to bump into the mountain! (Motto for all Innsbruck pilots, that!) Then, after a pause, ‘There was a bad incident recently, with a photographer … To be fair, he had more camera equipment than you … ’ This latter he says more kindly, and I am glad I have only brought two Leicas along. ‘The guy insisted on flying to the end of a valley – the very end – and just when the pilot said “Enough!” and tried to pull the plane round, he found he couldn’t because the telephoto-lens was caught under the joy-stick! They had to make an emergency landing, and it’s nothing short of a miracle they didn’t turn the thing over! That’s another rule of flying, by the way, always keep your eyes skinned for emergency landing places.’ My friend is in lecture-mode again. He casts an exaggerated glance out of the window, then nods back at me, satisfied. Meanwhile I hurriedly scoop all the lenses on to my lap. He seems perfectly calm now. Slowly and steadily we gain height.

‘Three thousand six hundred metres,’ he advises cheerfully. ‘Any minute now for the Wildspitze … ’

From my window I can see right into a high valley filled with hay-barns, a beautiful green valley running parallel to the Inn River, which by now has almost vanished into the distance. Such parallel valleys high in the mountains have an ancient, perhaps Celtic, name – ‘Tschy’. (That this was the Pfundser Tschy I did not know at the time, any more than did Charlie. Nor were we aware that the farmers would be haymaking there, scything the grass and spreading it to dry across this wide green valley at 1,500 metres, a valley hardly ever visited – perhaps no more than a couple of tourists go there in a summer … But, back to our flight!)

Impressive silhouettes of mountains and dark rocks float by on Charlie’s side, just as if they had been cut out with scissors. This must be part of the Kaunergrat, and I cannot resist leaning over for a moment – just this once – for a closer look. Charlie growls, banks the plane to a steeper angle and, yes, there it is, the Wildspitze! Over there!

How fantastic, the glacier world of the Ötztal! The engine labours with what seems to me a slight change in tone, but Charlie gives no sign of alarm and I continue gazing out of the window: the Ötztal peaks! It is twenty years since I was last here, as a young lad. Soon, I will spot all the old places! Thanks to Charlie and his kite. The plane shows little enthusiasm for the shining Wildspitze – the motor definitely sounds different now, more hollow. Is it anything? Surely, Charlie would tell me if something was amiss? He sits silent, just a bit hunched, and not sparing a glance for the Wildspitze. I take a photo of it, and another into the depths where suddenly a small emerald-coloured lake has appeared, set in a rocky cirque and surrounded by weird, eroded ridges, thrusting upwards.

What an abyss! It makes you dizzy to look at it. Hey, that engine noise is really most peculiar now – although I know nothing about such things – and I see Charlie fiddling with various buttons, turning them this way and that. No wonder he has lost interest in the landscape! I feel the blood rising, hot to my head: something is wrong! Is it serious? Charlie confirms my anxieties. ‘Get the bloody cameras out of the way,’ he bursts out. ‘The engine’s in trouble!’

It’s true, then. I swallow. Try to stay calm. ‘I thought there was something,’ I say. ‘It sounds just like an old car before it claps out.’

‘Don’t talk nonsense,’ my friend snaps. ‘It’s practically brand new – it can’t clap out. I’ve probably just got to change the mixture.’ He pulls another handle. (The reader, flying with us, must excuse the lack of technical precision: a cipher I am, merely, when it comes to things mechanical, having no idea how to fly a plane. You must rely on Charlie for that: after all he has been a pilot for a whole year. By now, even the most ignorant landlubber will have recognised we were in dire straits, with our stuttering huppada-huppada-hupp! Alarming, when that is all that holds you in the air.)

Charlie radios Innsbruck: ‘Charlie-Mac-Alpha, Charlie-Mac-Alpha – engine trouble, we have engine trouble.’ He has to speak English – all pilots do. Some practical advice obviously follows, which he tries out right away, and for a moment he succeeds in bringing the motor to a huppuppupp-uppup ... but our hopes are soon dashed: we are hardly moving forward at all, even though we stopped trying to climb ages ago. The aircraft rocks from side to side, like a boat on Lake Como in a light swell. (Would we were on any lake, rather than up here.)

‘Charlie,’ I hear myself saying, ‘let’s turn round and try to get down to the Inn valley.’

‘That’s our only hope,’ he retorts. ‘Don’t bother me now.’ And he calls up Innsbruck again.

This is a moment I know will live with me for ever – the swaying aircraft, the motor on its last gasp, those sharp ridges below and, at my side, Charlie clinging to the microphone as if it holds the key to our salvation. My thumping heart feels as if it is shrinking. Are we going to fall out of the sky? Yet, even terror has its tragi-comic moments. Charlie, gabbling into his walkie-talkie, forgets the rules and breaks into Tyrolean. There must be a different controller at the other end, unaware of how critical our position is. ‘Why don’t you speak English, Charlie-Mac-Alpha?’ the man says.

It is the last straw. ‘Stuff your English!’ yells a furious Charlie, as the propeller makes its last half-hearted revolutions – one, two ... oone, twoo ... o-n-e, t-w-w-o-o – then, quietly, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, coming to an oblique halt. ‘The bloody crate has died on me!’

He roars into the mike in his broadest Tyrolean, and suddenly no one gives a fig about the rules. The propeller has given up the ghost: no time for niceties. The aeroplane is still rocking gently like a little boat, but it hasn’t flipped over. Not yet. That means you won’t be falling out of the sky right away, a small, rational voice announces from some uninvolved centre of my brain, bringing transitory relief. But then, how long before you do fall once your engine cuts out? How many minutes have we got? Charlie is silent, hanging on to the steering with an abstracted expression. The plane continues its swaying. Seven hundred and fifty kilos it weighs, the same as a Volkswagen Beetle. A glance down reveals barren mountains, cirques, peaks rising from deep valleys, and over there, the Ötztal glaciers, shining, white ...

No, the two of us are not in a rocking barque on any lake: we are 4,000 metres up in the sky, in a Beetle-heavy plane without an engine, cutting through the air with a steady hiss. The slanting propeller, outlined against the white of the glaciers, slides gradually over the grey-green depths ... A chaos of rocks appears below us, a basin with a little lake.

Second birthday diagram here

‘Nowhere for an emergency landing there,’ Charlie says in a low voice.

If only we could get out of this thing.

How simple to break down in a car: with its last momentum, the driver can roll to the road side, then call out the rescue services. Seven hundred and fifty kilos would require a pretty strong guardian angel to hoist us out of trouble up here. How much longer now, before we hit the ground?

As if in answer to my thoughts, I hear Charlie say, ‘If we can maintain enough forward momentum, we can glide down.’ Glide? With this weight? Glide like a cockchafer, I think. But so far it seems to be working. Hoarsely, Charlie radios our position to Innsbruck – in English. ‘I’m trying to reach the Inn valley,’ he tells them, then turns to me. ‘Kurtl,’ he says, ‘I have practised this several times over the airfield. It’s going to be all right ... If we find somewhere to land ... If we don’t get caught in any turbulence ... and if ... ’

The thought of ‘coasting’ this box of tricks down imbues me with new hope. ‘The most important thing, Charlie,’ I tell him, ‘is to stay calm … ’ He is all for calling Innsbruck again, but I tell him that it is no use. We are on our own. Nobody on earth can help us. Our only hope now is to keep our heads, just as we did on Piz Roseg all those years ago, when80-metre séracs were poised above us, ready to break off!

Silence. Utter, utter silence ... apart from the hiss of air around the wings. Charlie, my friend, stay calm ... and I lay my hand briefly on his shoulder. We have everything to gain, everything to lose. I may not know how to fly this box of tricks, but I can help him not to panic.

What a strange coincidence that we should have bumped into each other today, that Charlie and I are together again, now, so many years after our big climb, linked once more as surely as by a rope, for better or worse.

What a stupid coincidence! Another voice intrudes in my mind: you would never have dreamt this morning that such a thing could happen. How come, after a year of flying, it should be today of all days that Charlie’s plane breaks down, and on our first spin together? A couple more minutes and it could be all over ... for good ... Never mind the thousands of dangers we have survived in the mountains! What irony! I can just imagine what the newspapers will make of it: MOUNTAIN AIRCRASH, CLIMBERS DIE FIFTEEN YEARS AFTER FIRST ASCENT. There will be gruesome pictures of scattered wreckage alongside our portraits. Bloody hell, that’s no way to be thinking! I have more important things to do …

‘Charlie, you’ll make it,’ I shout through the hissing air. He nods, grimly, clinging tightly to the controls and peering towards the Inn valley, from which we are still separated by a high mountain ridge. The expression on his face suggests he is calculating our chances of ‘leap-frogging’ over it. Luckily, we had climbed to over 4,000 metres earlier – now we are ‘living’ on that. The wings slice the air, we sink lower ...

‘Everyone makes it down!’ That is a macabre piece of pilots’ lore. But down where? We are still over a rocky amphitheatre, though there is more and more green ahead now.

Deeper and deeper we sink.

A map (not to scale) for the Second Birthday.

I seriously doubt we will clear this ridge which guards the deep furrow of the Inn valley. But shouldn’t there be that high valley pasture first, the one I noticed this morning? I look down, trembling with fear and anticipation. Never have I wanted anything so much as to be down there on firm ground, treading the sweet grass. Never have I been further from all that the earth means; only my thoughts touch it now: they want to melt into the ground, the rocks, the forests – all of which are coming closer by the moment. Yet though I long for this fusion, the moment of contact will almost certainly whisk me to infinity, into a world without space, beyond all that lies so far away, down there. My children … ? I think only how glad I am they have no idea what is happening to me. Perhaps they are just enjoying a fine day, somewhere down in the green.

It makes me so happy merely that they exist.

‘Charlie, I don’t think we’ll make it over that ridge!’

‘Depends on the air currents. It’s our only hope.’

No, no! Ahead of us, a bright green patch approaches, deep down, coming up now, rising above the jagged line of trees. It’s getting bigger, down in that wide trough, just before the barrier of hills. The high valley! It’s the Tschy! Look, look! Glinting up like a promise! I can make out wooden barns, see them quite clearly, sprinkled like tiny dice in the bottom of the valley. ‘Charlie, we can land down there! We don’t have to go over the ridge. It’s not that we know what’s on the other side anyway. Let’s put down here!’

My friend hesitates for no more than a second. ‘Right, here we go!’ And already we are banking almost vertically, the air rushing and swishing around the plane, our downward wing pointing directly into the bottom of the Tschy. ‘I’m going to spiral down now,’ yells Charlie through the noise, leaving me lost for words at this sudden change. Then begins a slalom to play havoc with the senses. It’s like being suspended inside a moving spiral staircase ... a chaos of sight and sound as we descend into the green cirque of the valley. Charlie has suddenly become a wondrous ski-ace, launching himself into the unknown in quest of ‘gold’. The ‘game’, increasingly difficult the lower we get, is played for life or death, countless spur-of-the-moment decisions where no error is permitted, swooping down a spiral staircase whose end is hidden from us – and where we need nothing short of the ‘gold’ to survive. From Charlie it demanded the utmost in ability and instinct, an almost overwhelming demand after only a single year’s experience.

Tighter and tighter grow the spirals as we etch whistling circles between the mountain flanks. Ours is an oblique world, the wings of the plane continuously above and below us. Charlie’s concentration remains absolute, his eyes staring fixedly ahead, his brow deeply wrinkled. Once I yell, ‘Watch out! Mind we don’t flip over!’ and he snaps back at me to shut up, saying, ‘You don’t know a thing about aerodynamics. Of course we’re not going to flip over.’ Our weird spiral gouges on into the depths, into this gigantic green funnel. I cling to the seat as the forest rotates 500 metres below; watching the wheeling treetops, I am still unconvinced we will not end up nose-first. Charlie wears a frozen smile, or is it a grimace of effort? He has the joy-stick in an iron grip. ‘You’re doing fine,’ I tell him. ‘Keep it going!’ And, however uncomfortable my position, it’s a fact, we haven’t dropped from the sky yet. We are still flying: increasingly it looks as if we might see this thing through. The earth appears much nearer now, and my longing for it has grown out of all bounds – as has my fear.

‘I’m going to turn the plane on its head – see if the motor will restart,’ Charlie announces suddenly. Every muscle in his face is tense.

‘No, no, don’t!’ I yell. ‘It’ll never work!’ Having come to terms with the spiral, I am reluctant to face another manoeuvre. But when Charlie is convinced of a thing, he does it: already we have gone into the headstand. Three hundred metres below are the roofs of the hay-barns, and small dots on the meadows – people – moving ... the rush around the wings has risen to a roar as they slice the air, the roofs grow closer, the people bigger – they are running. God, I wish I was with them! Charlie tries the ignition, but the propeller makes only a couple of feeble turns ... ‘It’s not going to work!’ he curses. And down there, suddenly, the roofs disappear from view and the mountainside arcs steeply upwards in front of us, as we are pressed into our seats with full force. Blue sky? Clouds? Whatever is happening now? Panting, Charlie holds – no, leans with all his strength – against the steering. We’ve had it, then, I whisper to myself, just another couple of seconds ... I want to say something to Charlie, but my throat narrows and nothing will come. I am suddenly overwhelmed by a sense of weightlessness, and at the same time, of helplessness ...

‘Charlie ... ’ A glance across shows his face distorted, his eyes mere slits. That was it then, Charlie, was it? Suddenly the weightlessness vanishes and in its place an immense pressure seizes me: my arms are lead, my body is lead. The seat, the elbow-rests thrust up at me with great force, countering gravity. But we must be falling ... aren’t we?

For a moment I do not know what’s happening.

Charlie draws a deep breath. ‘That was hairy,’ he says. No, we aren’t falling any longer, we are hanging once more sideways in the air. ‘We must choose somewhere to put it down,’ says my Charlie, ‘There’s not much time left.’ He is maintaining the curve. I feel life has just been given back to me, I am thankful for every extra moment. But now, God, another decision! Those meadows, which looked so smooth from above, we see are full of bumps. And the valley is dotted with hay-sheds, fatal wooden cubes: we don’t want to smash into them. There is a ditch, too, beside a narrow dust road.

‘Go higher up the valley,’ I call instinctively. ‘Charlie, over there!’ And I point ahead.

‘Yes, that’ll do,’ he yells back and is flying now straight towards a meadow immediately above the dust road, which looks more promising. It is racing towards us – oh, hell! It is just as bumpy! ‘Can’t do anything about it now,’ Charlie mumbles, ‘I’m lowering the flaps.’ A second later, I hear the rush of air. A couple more seconds, and all will be decided, one way or the other. It is almost a relief. The earth is close. I am full of hope.

The road! There’s a farmer, running; he throws himself into the ditch, but already we have swooped over him. Again I hear Charlie. ‘When we’re down, try to get out right away. If that’s possible.’ His voice sounds urgent. Roofs skim past ... a big grassy dome approaches – there? No, not there! That’s it, no more choices ... no time ... The road! The road with the ditch – here too! We’re still moving at a hundred kilometres per hour, we’ll just get over it …

‘Tuck in your legs! Any minute now … ’ Charlie roars over the noise. Fractions of seconds, fragments of time: the green dome, again ... there are humps behind it, too! In between ...

CRAAAAAASH! Then a wild kick, and we are flying again, thrown up with enormous force. We flop over the hill, an enormous jump of at least forty metres! CRAAAAAASH! I hug my legs, bent, hanging in the harness. And we’re airborne again, like a football. Will it never end? CRAACK! That was very hard, that one! Another jump – into the air – PRANGGGGGG! At last we seem to have come to rest. GET OUT! QUICK, OUT, OUT! In a fraction of a second I am free of the harness, hurl open the door, and I am outside!

The world does not move any more.

The meadow. The grass. The flat, still ground.

My feet are planted back on earth. I feel it coming up through every fibre of my body, from the surface – life. It is a miracle.

‘Kurtl!’ Charlie laughs crazily, ‘We’re alive!’ And I see him pulling at his hair and running round and round in the meadow, like a lunatic. And I’m running through the grass too, deliriously shouting and screaming. And we fall on each other’s necks, hug one another and gallop round again. We are totally beside ourselves – over the edge with joy. Here we are, here we are ... we are alive!

‘Kurtl,’ Charlie yells suddenly. ‘You might not know how to fly, but you’re the very best companion for a crash! Without you, I’d have been really nervous!’

‘Charlie … ’ I say. But I cannot say anything: all of sudden I have no more words. Charlie, I think, without you ...

To Charlie, I owe my life, my second life – that’s why he is here, at the beginning of my book – even if his real name is Karl Schönthaler and not Charlie at all. Forgive me, Karl …

What else remains to be told?

A lot: we had been incredibly lucky. The aeroplane didn’t catch fire, we didn’t nosedive, or turn it over, we didn’t even break any bones – nothing at all! Charlie walks round his plane in sheer disbelief: ‘The only damage is to one of the struts. And at the back, there’s a little bit torn away. That’s all! And we are alive!’

Beside ourselves with happiness, we are standing in our flower-decked ‘birthday meadow’, 1,500 metres above the sea, in this beautiful Pfundser Tschy, as the first farmers, men, women, boys and girls come flocking round. They look at us as if we had risen from the dead and shake our hands. Some shake their heads as well. A farmer’s wife remarks with feeling that you would never catch her sitting in one of these contraptions …

Straightforward country people, who do not waste a lot of words; we are happy they came; we are happy about everything. Happy beyond measure, beyond words. Real birthday kids! And into this ‘contraption’ which Charlie has just coaxed safely out of the sky, this box with which he struck ‘gold’ for us – our lives – I, too, will never venture inside. Never again.

Everyone living in the high valley had to come and visit this meadow, of course. At first glance you would never know the plane had made an emergency landing, even if it was standing a little cock-eyed. Only closer inspection revealed the cracked strut and damaged rudder. By chance, in the afternoon, two German tourists dropped by – and they had heard nothing of our drama. One of them, a well-fed man with a shaving-brush of chamois hair on his (new) hat, remarked to his wife, ‘Did you realise, Wilhelmine, that these Austrian farmers are now flying in to harvest their hay?’

I guarded the plane next day, in case it became an irresistible ‘toy’ to the children of the valley, and there were even more visitors. I had to explain over and again what happened. But I didn’t mind, I could have stayed for days in this meadow. Charlie had gone down to the Inn valley to find a mechanic and some heavy vehicle that could tow us. The whole plane would need dismantling screw by screw to load it on to a transporter and get it down to Innsbruck.

… Later, I have to say, Charlie preferred to buy a new plane.

1. It was the direct north-east face of the Piz Roseg that Karl Schönthaler and I climbed in 1958, at that time the hardest route in the Bernina group. It still belongs in that category. The first direct exit from the Klucker route over the ice bulge of the north summit also fell to us.[back]

Double Solo on Zebru

Monte Zebru (3,735 metres)[1] looks like the raised fin of a giant fish. Sunlight, catching its north-east face obliquely, reveals a fine design like radiating bones. These are snow and ice ribs, varying in number according to the prevailing conditions on the face. Up to the right, the piscine image is fortified by an overall pattern of dark speckles – islands of rock penetrating the thin skin of snow and ice. The top edge of the fin runs more or less horizontally, though it carries a summit-point on either end. The face below the one to the right – the northern – was unclimbed from this side, although a route had been pushed to the south summit, up a completely white flank which lies almost always in shadow, being inclined towards the north. There is a plinth of out-cropping rock at the base of the fin, surmounted by a small hanging glacier – except that nothing is really ‘small’ here. The height of the face itself is some 700 metres. My two-fold climb of this giant fin took a full day, giving many adventurous hours: a first ascent to the north summit, followed by a first descent from the southern summit, both solo.

In some way it was another birthday.

I was climbing on my own because my friend Albert Morokutti’s leave had run out before I felt ready to go home. I don’t really consider myself a soloist; I far prefer sharing an adventure with someone else. That is not to imply anything against solo mountaineering: it is just a different kind of experience, often more dangerous, sometimes more intense, and one which takes you to the limits of existence – no other human can help you find the answers, only the mountain … and yourself.

Thinking about this climb, I sat alone in the hayfields of the Pfundser Tschy, waiting for Charlie to organise recovery of the damaged plane.

What brought it into my mind? During my solo on Zebru all those years ago, just as in the crippled aeroplane, there had been moments when I longed for some good flat earth beneath my feet. And it had been just as far away.

***

A thirty-metre hemp rope over my shoulder, some pitons in my rucksack and an ice axe in my hand: that’s how lightly I set out for Zebru. The hut warden had thoughtfully provided a couple of sandwiches, but these weighed scarcely anything, and my rope was quite thin – sufficient only for a self-belay on some of the more difficult passages, or for abseiling if it became necessary to retreat – you never know.