9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Vertebrate Digital

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

'A monumental book … I defy anyone to read it and remain unmoved.' Stephen Venables, Alpine Journal Acclaimed as one of the most powerful accounts of mountain adventure and tragedy ever written, The Endless Knot is a harrowing account of the 1986 K2 disaster. A rare first-hand account from a survivor at the very epicentre of the drama, The Endless Knot describes the disaster in frank detail. Kurt Diemberger's account of the final days of success, accident, storm and escape during which five climbers died, including his partner Julie Tullis and the great British mountaineer Al Rouse, is lacerating in its sense of tragedy, loss and dogged survival. Only Diemberger and Willi Bauer escaped the mountain. K2 had claimed the lives of 13 climbers that summer. Kurt Diemberger is one of only two climbers to have made first ascents of two 8000-metre peaks, Broad Peak and Dhaulagiri. A superb mountaineer, the K2 trauma left him physically and emotionally ravaged, but it also marked him out as an instinctive and tenacious survivor. After a long period of recovery Diemberger published The Endless Knot and resumed life as a mountaineer, filmmaker and international lecturer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The Endless Knot

The Endless Knot

K2, Mountain of Dreams and Destiny

Kurt Diemberger

Translated by Audrey Salkeld

www.v-publishing.co.uk

.

For Julie,

and for all those who come to

touch these great mountains.

Contents

Acknowledgements

K2 from both sides

Introduction

Biography

K2 … The Peak we most Desired

The Lonely Mountain

The Boat

Dream Mountain – K2 from the North

England – Tunbridge Wells

Italy – Bologna

Raid on Broad Peak

Tashigang, Place of Happiness

Jinlab – the Magic of the Mountains

The Village on the Moraine

Threats Posed to Health by High Altitude

Success and Tragedy – Russian Roulette?

Julie Has Doubts

The Ice Avalanche and the Riddle of the Teapot

The Decision – We Go Together

Pushing to Great Heights

The Korean Tent

The Key Factor – A Tent

The Lost Day

The Summit – Our Dreams Come True

The Fall

Down to 8,000 metres

Blizzard at 8,000 metres

Flight from the Death Zone

Where is Mrufka?

Perpetuum Mobile

Clouds From Both Sides

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

Acknowledgements

I could never have finished this book without thinking all the time of Julie and her wish, to pass on to others what we were living for. Besides herself it was Julie’s understanding husband Terry, her early climbing partner Dennis Kemp and – perhaps in the most significant way – her martial arts teacher David Passmore who opened up a world for her that was very special.

To write about these events on K2 was hard and it took me almost two years to complete the book. I want to thank my wife, Teresa, for her incredible patience. Many others helped too: Audrey Salkeld who translated the book into English; Choi Chang Deok who helped me clear up some of the mystery hidden in Korean hieroglyphs; Charlie Clarke and Franz Berghold, high altitude illness specialists; Xavier Eguskitza, John Boothe, Peter Gillman, Judith Kendra and Dee Molenaar … even my daughters, Hildegard and Karen, have contributed to this work.

I must also thank those who made it possible for me to start writing at all: Gerhard Flora in Innsbruck and Hildegunde Piza in Vienna, who treated my frostbite, Enzo Raise in Bologna and the staff of Pembury Hospital in Sussex. Mrs Susi Kermauner in Salzburg took me to her rusty typewriter to start my first chapter and months later my little son Ceci taught me how to use the computer. There are many others who are not named.

Julie’s book now has a companion – The Endless Knot – here it is.

Kurt Diemberger

March 1990

K2 from both sides

K2 from both sides, that was to have been the title of this book. Julie and I wanted to write it together. On my own, now, I find myself fighting shy of getting started.

Come on, Kurt!

Well then: testing, testing … This typewriter seems all right, the ribbon is new and all the keys are functioning. The only thing that’s needed is for the builders on the roof outside to stop their bloody noise. A neighbour on the other side was mowing his lawn all morning – that, at least, has finally stopped – unless he is simply taking a rest. Perhaps a nip of whisky will help me face all these distractions. I must type with my thumb because the fingers of my right hand are still too painful to use. Fingers, I say – I mean what’s left of them after the frostbite.

Perhaps I can at least set my ‘new’ index finger to work – that’s not too bad. I wonder if Susie has a finger-stall? Using only the thumb makes it hard to concentrate on what I want to say. I should try dictating into a tape recorder, I suppose, and then type it up – that way it would just be a mechanical action, and it wouldn’t matter whether it was comfortable or not. But you do need peace and quiet to write on tape – not for the writing, exactly, I mean for the recordddddddddddddddddddddddddddd

dddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddding.

The ‘d’ got stuck. C’est la vie! Difficulties are there to be overcome. I fiddle the typewriter key backwards and forwards, until at last it moves freely again (the arm of the letter key, I mean.) Now … where were we? Ah, yes … I mean for the recording. The one person you could have in the room would be the person to whom you’re telling the story – that’s the only possibility. Otherwise, you have to be totally on your own, and with no interruptions, so that you can ‘find the centre’ – as Julie so often used to say – and which she explained best, perhaps, in connection with meditation – or with the martial arts like Aikido or Budo. There the ‘centre’ has its importance not only for your mind, but also your body. Oh, those damned builders! The noise of sawing boards chases all thoughts out of your head. Today, I can see, is going to be a battle against innocent opponents. But perhaps it will also reinforce my resolve, since this book is something I really want to write – for Julie, for me, for all those who understand. It seems senseless to have lived through all this only to have it disappear without trace.

Even then, it would not have been meaningless. It made sense for both of us at the time, representing the fulfilment of a lifetime … It is about realisation I want to tell, a realisation that took place over only a few years, years during which K2 stood over us, remote and chill, yet more beautiful than any other mountain. A symbol, it seemed, of all that is unattainable.

An eternal temptation.

‘Will we ever come back to K2? Of course we will.’ (Julie Tullis, 1984, in Urdokas on the Baltoro Glacier)

Introduction

A real book needs more than just a good writer. It needs a deep conviction, a promise to yourself, to others. I could never have finished this book without thinking all the time of Julie and her wish, to pass on to others what we were living for, to have them participate – and writing down our experiences made it real. It was a way of continuing our team, a conviction that grew during my lonely descent on the Abruzzi after the fatal blizzard. It was a promise. Thus, the mountain and our thoughts will be within these pages.

‘Anything is possible’, Julie used to say. She had a very strong will, was positive, determined and active. However, at times she would just sit still, listen to the sounds of nature, let her mind glide away into the space between the leaves of a tree, between the shimmering walls of ice towers, or up to the clouds beyond them. It was not only Julie herself who made our great days, those years – and with them, this book – possible. You almost never find that your achievements, your dreams, become real without the actions, influence or help of others. Besides herself, it was Julie’s understanding husband Terry, her early climbing partner, Dennis Kemp, and – perhaps in the most significant way – her martial arts teacher David, who opened up the world for her very special, uncommon personality. Julie has dedicated several chapters of her beautiful book Clouds From Both Sides to them.

When I wrote this book I considered also how much it might mean to her friends. Our time in the Himalayas were her last years, bringing her the greatest fulfilment as a creative person, not only with the summit of K2, our dream mountain. It was a way of ascent to yet another realisation. Then it all ended abruptly in the blizzard at 8,000 metres.

To write about the events up there was hard, sometimes a real struggle, but it had to be. I’ll never be able to accept what happened, but at least it should never be repeated. It took me almost two years to complete the book, and I want to thank Teresa, my wife, for her incredible patience, as well as Audrey Salkeld, who translated the book, for hers. Many people helped: Choi Chang Deok, a priest, was sent to me, perhaps by providence, to clear up the mystery of this tragedy, hidden in illegible Korean ‘hieroglyphs’; Charlie Clarke and Franz Berghold, high altitude illness specialists; Xavier Eguskitza, the indefatigable chronicler, John Boothe, Peter Gillman, Judith Kendra, and Dee Molenaar … even my daughters Hildegard and Karen have contributed to this work!

And I must not forget those who made it possible for me to start writing at all: Gerhard Flora in Innsbruck and Hildegunde Piza in Vienna, who treated my frostbite; the Pembury Hospital in Sussex which saved me from a sudden lung-embolism in the aftermath of K2; Enzo Raise in Bologna, who recognised at the last minute my totally unexpected malaria, probably caught on my way home in the aeroplane – I almost died from it. While I slowly recovered, Mrs Susie Kermauner in Salzburg took me to her rusty typewriter in that two-hundred-year-old house … and I started the first chapter. Several months later, in Bologna, my little son Ceci interfered with tradition: he taught me how to use the computer! ‘Oh, finally, Dad … ’ he said.

Even if their names are not given, I want to thank many more people that Julie’s book now has a companion, The Endless Knot; here it is.

.

Kurt Diemberger

Bologna, March 1990

Biography

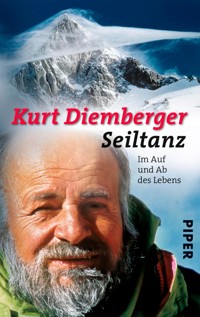

Austrian mountaineer Kurt Diemberger is a member of an extremely select club – he is one of only two climbers alive to have made the first ascent of two of the world’s 8,000-metre peaks, Broad Peak in 1957 and Dhaulagiri in 1960. Diemberger is also an accomplished filmmaker and writer, he became one of the top high-altitude filmmakers in the world and his books have enjoyed popularity around the globe. He is now recognised as one of the finest chroniclers of the contemporary mountain scene, with his writing guaranteed to enlighten, move and entertain. In 2013, Diemberger was awarded the Piolets d’Or lifetime achievement award.

Born in 1932, Diemberger began mountaineering in the Alps, quickly notching up an impressive list of ascents. By 1958 he had climbed the three great north faces of the Alps – the Eiger, Matterhorn, and Grandes Jorasses. He soon turned his attention to the Greater Ranges, where he made several notable and first ascents, often without oxygen.

Both of his 8,000-metre first ascents were made without additional oxygen and Broad Peak, which he climbed with Hermann Buhl, Marcus Schmuck and Fritz Wintersteller, was the first eight-thousander to be ascended in alpine style, (renouncing help from high-altitude porters and artificial oxygen and without backup from base camp), long before this technique became widely used on the Himalayan giants. In all, Kurt has climbed six of the eight-thousanders, and Broad Peak twice (the second time in 1984 with Julie Tullis, 27 years after his first ascent).

Diemberger’s mountain film career began in 1958 when he filmed the greatest ridge-traverse of the Alps – the ‘Peuterey Integral’ on Mont Blanc, including the Aiguille Noire and Aiguille Blanche – from a rope of just two (his patient partner during the five-day climb was Frans Lindner).

He then filmed the first ascent of Dhaulagiri in 1960, made films in Greenland, the Hindu Kush and in Africa, and in 1974 took his 16-milimetre camera up the ‘traverse of the future’ on Everest when he reached the top of Shartse (7,500 metres), having made the first ascent with his friend Hermann Warth – leaving the continuation of the enormous ridge traverse via Lhotse and Everest for others still to come.

Later, in autumn 1978, Diemberger succeeded in making a sync-sound film on the top of Everest itself, recording his French companions and making a complete 360-degree panorama with his cameras. It was a world-first and, for Kurt, a keen photographer from his earliest visits to the Alps, a ‘crowning moment’.

Diemberger made several award-winning documentaries with Julie Tullis, his high-altitude filming companion and ‘other ego’ in later years. These included three films on K2, where the pair entered the field of documentaries on local people in the Himalaya with ‘Tashigang – a Tibetan village between the world of humans and the world of spirits and mountain gods’.

Both had great ideas for filming in this area, and they would have continued their creative union but Julie, after reaching the summit of their dream mountain K2, died in a long-lasting blizzard during the notorious ‘black summer’ of 1986, which claimed the lives on 13 climbers on K2.

Behind K2, in the Shaksgam wilderness, a drum full of gear has been hidden since 1999 and Kurt, after seven previous visits, hopes to return for future exploration. When he was awarded the Piolet d’Or for lifetime achievement in 2013, it was not just for having climbed so many north faces, or having overcome the Giant Meringue of the Koenigsspitze (then far ahead of similar ‘stunts’), but for what he had created during his mountaineering careers for all others with his camera, images and writing.

K2 … The Peak We Most Desired

A strange, filmy mist has settled over everything – a grey silk shroud cloaking the entire pyramid of the summit, fascinating and menacing at the same time. There is tension in the air: it runs through us, through this steep, snowy landscape with its undulations and ice cliffs. The weather is slowly worsening.

All the same, we keep climbing. It can’t be much further now. If we’re caught in a storm up here, up at almost 8,600 metres, we haven’t a hope of surviving whatever we do. Whether we turn back or not. This way, at least, we shall have stood on the summit – ‘our’ summit – first.

A vertical wall of ice rears out of the silky light. With my ice-axe I turn a titanium screw into its hard surface. It creaks and grinds. Then I cut a couple of holds – no time to waste on artistic effect at this height. Will there be more obstacles above this? Or will we see the summit in a few minutes?

Julie belays me as I move up cautiously. Just a few metres and I am over the ice barrier. And there it is! In the soft, grey light, the highest billow of snow on this high mountain – the summit of K2. It looks so gentle – easy even – this final curve, after the terrible precipices below. A wave of happiness washes over me. ‘Up you come, Julie! Come on, we’re almost there!’

She appears over the edge, craning to see over its icy rim. Elbows in the snow, she stops to gaze upwards. ‘Be still!’ she whispers, and I see surprise and wonder in her eyes, those dark, familiar eyes under the frosted strands of hair. She seems to be in silent communion with the last smooth curve of snow.

What goes through her mind? I wonder. What is she telling those summit snows?

For three years we have lived with the dream of coming back to this, our mountain of mountains … Now the elusive summit is within grasp. Nothing can take it away from us.

But it’s late. And the weather is about to break. In a strange way, it seems to be holding its breath, granting us a few moments’ grace. Yet, even though it looks a little brighter, the magic light cannot deceive us.

‘Julie, let’s go!’ Suddenly I feel uncomfortable.

She looks up with a smile, as if returning from a distant world ‘Yes, let’s get a move on! Let’s get up there!’

Within minutes, our three-year dream will be fulfilled.

The Lonely Mountain

Thirty Years Earlier – On the Baltoro with Hermann Buhl

Shshsht! Shshsht! Shshsht! Shshsht! Our snowshoes glide over glistening, sunlit powder, across ribs of ice and the gently rolling curves of the glacier.

Ahead of me, still pushing strongly despite fatigue and moving with short, precise steps, is the small, almost delicate figure of Hermann Buhl, his energy clearly visible as he covers the irregular ground of the Godwin-Austen Glacier. I can see his grey, wide-brimmed felt hat above his rucksack, his fine-boned hands resting on the ski-sticks for balance each time he raises one of the oval, wooden snowshoes to take another, sliding step, but the expression in Hermann’s ever-alert eyes as he scans the way ahead, I can only guess at. Thus, we make our way forward, past long rows of jagged ice-shapes, as if in an enchanted forest where everything has been frozen into immobility. Corridors between the towers lead us along the spine of the moraine, through freshly fallen snow.

We are alone – alone in the heart of the Karakoram, surrounded by mighty glaciers, in a savage world of contrasts, of ice and rock, of pointed mountains, granite towers, fantasy shapes rising a thousand metres or more into the sky, some very much more.

This spring (May 1957), besides Hermann and me and our three companions back in Base Camp, there are no other human beings on the whole of the Baltoro Glacier.

Marcus Schmuck and Fritz Wintersteller from Salzburg and Captain Quader Saeed, our liaison officer (who, having no one to liaise with, has been homesick for the more colourful life of Lahore for several weeks now), are fellow members of the only expedition this season within a radius of several hundred kilometres. We are alone on this giant river of ice, fifty-eight kilometres long, which with its fabulous mountains constitutes one of the remotest and most beautiful places on earth. Uncounted lateral glaciers fan out to peaks of breathtaking size and steepness – forming compositions of such harmony that they seem to emanate magic – to places where no one questions ‘Why?’ because the answer stands so plain to see. My great ambition, to go once in my life to the Himalayas and climb the highest peaks in the world, has been realised – at the age of twenty-five. Hermann Buhl invited me to join his team on the strength of my direttissima climb of the ‘Giant meringue’ on the Gran Zebru (Königsspitze), a sort of natural whipped-cream roll widely considered to be the boldest ice route in the Alps to date. I’m ecstatic. Everything I have, I will put into this one big chance.

Now, as we make tracks in the snow at almost 5,000 metres along one of the lateral glaciers (having set off from close to Concordia, the Baltoro’s kilometre-wide glacier junction), my thoughts turn to the early explorers. The glacier we are on is named after the cartographer Godwin-Austen, one of the first to set eyes on the Baltoro in the middle of the last century; but Adolf Schlagintweit was probably the first non-local to get close to the Baltoro area and to reach one – the western – of the Mustagh Passes (Panmah Pass). He has not been commemorated by any name on the map. On the other hand, the beautiful, striated glacier across Concordia from us is dedicated to the traveller G.T. Vigne, who never set foot on it. Martin Conway, leader of an expedition in 1892, was the first to come to the Karakoram to mountaineer; he was later knighted and a snow-saddle he discovered was named after him.

We are not explorers in the same sense as those men, yet on a personal level that is exactly what we are. Going into an empty landscape like this, among giant mountains, your heart quickens and the prospect around the next corner is no less seductive to you than it was to the first people who were here. The same silence dominates the peaks, the same high tension arcs from mountain to mountain; days can still seem like a true gift from heaven. So it is with us on this morning.

Above us soars Broad Peak. No man has ever climbed its triple-headed summit, which rises into the sky like the scaled back of a gigantic dragon. For me, the very rocks breathe mystery: nobody has touched them. I am happy that this mountain, one of the eight-thousanders, is the target of our expedition. But today, Hermann and I are heading off towards K2.

The tallest pyramid on earth seems to grow steadily before our eyes in its unbelievable symmetry. Many years ago, British cartographers[1] computed the height as 8,611 metres: 237 metres lower than Everest. The second highest mountain in the world is, however, considerably the more difficult of the two to climb and is without doubt one of the most beautiful mountains in the world.

The international expedition of Oscar Eckenstein, which included the Austrians Hans Pfannl and Dr Victor Wessely, made the first attempt in 1902 and managed to reach 6,525 metres on the North-East Ridge. But in 1909, a large-scale expedition led by the Duke of the Abruzzi opened up the South-East Spur (the Abruzzi Ridge or Rib), revealing that as the most favourable line of ascent. They only got to 6,250 metres, but on nearby Chogolisa (Bride Peak), the Duke and his mountain guides clambered to 7,500 metres, which stood as a world altitude record for many years. They were only 156 metres from the summit.

Hermann Buhl has stopped to look across towards Chogolisa, that shimmering trapeze of snow and ice, maybe thirty kilometres away. ‘A lovely mountain,’ he says.

To me, it looks like an enormous roof in the sky, but Hermann’s attention is already back with K2. ‘Such a pity that’s been climbed already! But wouldn’t a traverse be great; up the ridge on the left, then down to the right, by the Abruzzi?’ And he tells me all he knows of the Abruzzi route, how the mountain was first climbed this way by a huge Italian expedition three years ago. They put in no fewer than nine high-altitude camps. And, it’s said, fixed 5,000 metres of rope on the ridge itself. Ardito Desio, a professor of geology, was leader and the two summiteers among the eleven-man team were Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni. It was a national triumph, which threw the whole of Italy into a whirl of rejoicing. It is true that they used bottled oxygen, but it ran out towards the end. And they didn’t give up! Hermann is laughing, ‘So you see, it does work! You can do it without!’ Then he tells of George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, who never came back from a summit attempt on Everest in 1924, despite taking oxygen. Nine years after their disappearance an ice-axe was found at 8,500 metres which can only have belonged to one of them, yet today we are no nearer knowing whether they made it to the top of the world or not. And he tells of Colonel Norton, who went very high on Everest without oxygen, and of Fritz Wiessner, who got within almost 200 metres of the top of K2 in 1939, also without using it.

I can see from his animation, from his eyes and gestures, that Hermann can hardly wait to have a go at K2, without oxygen or high-altitude porters. ‘In West Alpine style’ is the phrase he coined for it. ‘Mmm!

K2 is a beautiful mountain and no mistake,’ he concludes, adding pensively, ‘and the way to do it is definitely up that left ridge, down the right.’

But the mountain looks so high, like nothing else in the world. We are only tiny dots before this huge mass, which shines like crystal from the snow and ice on its faces. It arouses no desire in me. I am happy with our choice: Broad Peak is still virgin, and almost 600 metres lower than K2. Better for our ‘West Alpine’ enterprise – already considered crazy by a lot of people – better than the second highest mountain on earth!

With that, my thoughts turn to ‘our’ eight-thousander: the only time it was ever attempted was in 1954 by a German expedition under Dr Karl Herrligkoffer. They found it pretty hairy. Following a line under constant threat from avalanches, the climbers discovered that huge blocks of ice had stopped only inches short of their tent. One day the Austrian Ernst Senn fell down a sheer 500-metre ice wall, whistling along like a bobsleigh to land (by incredible good fortune) safely in the soft snow of a high plateau. At 7,000 metres, icy autumn storms drained the men’s last reserves of energy, forcing them at length to abandon the attempt.

A few days ago, buried in the steep ice of the ‘Wall’, we discovered a German food dump with advocaat, angostura bitters, some equipment … and a three-year-old salami, which still tasted all right. There was even a tin of tender, rolled, Italian ham, a well-travelled delicacy which quickly found its way into our stomachs. I have to confess that this side trip we’re making to K2 is purely out of curiosity, to see what delicious titbits might still be lying around at the site of the Italian Base Camp!

A delusion: all our efforts to find the camp fail. The wide glacier is white and pristine, and there is no trace on the moraine either. Finally, we turn around and waddle on our snowshoes back the way we came.

It was curiosity, too, that led us to penetrate the avalanche cirque of Broad Peak. Hermann wanted to take a look at the route Herrligkoffer had chosen. The doctor had been his leader on Nanga Parbat and there was no love lost between the two men. Hermann himself had opted for a more direct line on the West Spur of Broad Peak, a line of greater difficulty, it’s true, but very much safer, and one that had been recommended by the well-known ‘Himalayan Professor’, G.O. Dyhrenfurth. A straightforward and direct ascent like this is much more in Hermann’s style.

As we approach Base Camp, tired now from dragging these legs with their wooden appendages, kaleidoscopic memories dance through my mind. I remember how, amid a swirl of dust, we touched down in the old Dakota on that sandy patch of ground near Skardu which serves as an airfield; remember crossing the Indus river in a big, square boat: the three-week-long walk-in, following first the wide Shigar valley with its blossoming apricot trees, then through the Braldu gorge, and finally trekking up the Baltoro Glacier with our sixty-eight porters … remember being slowed down by snowstorms, so that our loads were dumped twelve kilometres short of Base Camp. The subsequent load-ferrying, backwards and forwards with 25-30 kilograms on our backs, went on day after day until Base Camp was at last established at 4,900 metres – that is higher than the summit of Mont Blanc. And Hermann’s words of consolation, ‘It’s all good training for later on … for the first eight-thousander to be climbed in West Alpine style.’ Then the West Spur itself: up and down, up and down, plagued at first by headaches … Later it went more easily. Whenever we set down our loads at Camp 1, we would squat on our haunches in the snow for a fast slide down into the depths again.

After a while, even taking every precaution, we could manage the 800-900 metres of descent on the seat of our pants in just half an hour!

Seen from Concordia, Broad Peak – this three-humped dragon – has the appearance of a mighty castle. From wherever you see it, it always looks different. You can never ‘know’ a mountain precisely … When we finish here, Hermann hopes to have a go at Trango Tower, or one of the other fantastic granite spires in the lower Baltoro.

We are a modern expedition. Hermann has seen to it that we lack nothing progress has to offer. We have gas cylinders – huge ones like those for domestic use, each a full porter-load – and small ones of about 7 kilos for higher on the mountain. We have simple ridge tents, extremely stable. And advanced altitude boots of heavy, solid leather, made especially roomy to accommodate socks or felt slippers or whatever else we feel like using for insulation … newspaper works quite well! Of course, walking on moraine in these Mickey Mouse boots is awkward – you feel like deep-sea divers. No doubt one day someone will come up with a custom-made boot-within-a-boot that is a lot better. But we are not ill-satisfied. Except for one thing: progress dogs us even on the West Spur in the form of a walkie-talkie apparatus weighing 11 kilos. We decide to dump it at Camp 1 (5,800 metres) and from there on use the time-honoured method of a piece of paper: write down what you want to say and leave it in the tent for the others to read when they get there.

Camp 2 is a natural snow hole, which we have enlarged, under the rim of a high plateau at 6,400 metres. We have even set up a kitchen there: Hermann has this weakness for potato dumplings, ox-tongue salad, mayonnaise, and buckthorn juice – in other words, for all things sour – and for beer. But the latter is only available at Base Camp. He calls it Nature’s Own Sleeping Draught. His first ‘dose’ turned into a foaming fountain, a metre high, which only stopped gushing when the blue Bavarian tin was empty. Barometric pressure is quite different at 4,900 metres, and we soon learned to make only a tiny puncture and to keep a thumb over the hole so that the pressure could be released slowly and our nice sleeping draught not sprayed to the four winds.

The days pass. On 29 May, we push up from Camp 3 (just below 7,000 metres) towards the summit ridge. We make it as far as the northern end of the ‘roof’, that is to a height of about 8,030 metres. Only then do we discover that isn’t the top: the opposite end of this enormous ridge is just a bit higher. But it’s too late in the day. We descend. Back in Base Camp, we know we have to retrace our steps all the way up the mountain again – just for those extra twenty metres of height at the other end of the ridge. There’s no way round it: that is the summit!

Marcus and Hermann both have frostbite on their toes, and Hermann calls for the ‘doctor’. That’s me! Uncomfortable in the role, but using the calming words of a real doctor, I give him an injection. Then another one. Success! I was appointed expedition ‘doctor’ only a month before our departure. Hermann justified it by saying, ‘Well, you’ve studied, haven’t you?’ My protestation, ‘Yes – but commerce,’ was not considered sufficiently valid an excuse for refusal. He must have great trust in me.

We had 27 kilos of pills and potions (assembled by a real medic) and a universal tool for pulling out teeth (which fortunately I, as Medicine Man, have not been called upon to use). During the long walk-in I have been approached by many of the locals for treatment. I did what I could, relying when in doubt on my bag of painkillers. Nobody should come to any harm, at least. (After all, we do have to go back the same way!)

The big day – 9 June. One after the other, all four of us reach the summit of Broad Peak. Even Hermann, in the end, despite his frostbite. He had given up at 7,900 metres, but afterwards changed his mind. On my way down from the top, I came across him still plodding upwards and turned to accompany him. As the day faded, this unique day, we stepped together onto the highest point …

It was about 7 p.m., the sun low in the sky, as we stood there … a moment of truth. The silence of space surrounds and holds us. It is fulfilment. The trembling sun balances on the horizon. Down below, it is already night, over all the outstretched world. Here, only, and for us, is there still light. The Gasherbrum summits shine close by, and further away comes the shimmer off Chogolisa’s heavenly roof. Straight ahead, against the last of the light, soars the dark profile of K2. The snow around us is tinged a deep orange, the sky a pure, clear azure. When I look behind me, an enormous pyramid of darkness is thrown across the endless space of Tibet. It is the shadow of Broad Peak! A beam of light reaches out above and across the darkness towards us, striking the summit. Amazed, we look at the snow at our feet: it seems aglow. Then the light disappears … (from Summits and Secrets)

It was the great sunset for Hermann Buhl, his last on any summit.

In all truth I admired K2 from up there, that massive wedge of deep blue, like a cut-out against the flood of light, But still I felt no desire. The mountain was too big, unapproachable, easy to leave alone. No thought crossed my mind then that it was to play such a decisive role in my life. Only much later did Eric Shipton’s words draw me under its spell.

1. T.G. Montgomerie in 1856 (see Appendix 1). More recently, Professor Ardito Desio’s 1987 expedition – which I accompanied as cameraman – remeasured the heights of several peaks in the Himalayas by GPS (Global Positioning System, using Navstar Satellite Signals), and found K2 to be 8,616 metres, and Everest 8,872 metres. However, for the time being the official height of K2 is still 8,611 metres, while Everest is now given as 8,850 metres.[back]

The Boat

Meeting Julie

Can that be Sirius, that bright star?

No, not in summer. It must be one of the larger planets.

The way it twinkles, it seems almost to be dancing in the darkness behind the mainstay, mimicking the movements of the boat.

When the star moves too far from the dark line of the stay, I gently press the tiller until the catamaran is once more on the right course – for England. From time to time, after glancing at the illuminated compass, I look for a new star … because everything turns endlessly, even the sky above the North Sea. I prefer taking my bearings from the stars, rather than referring constantly to the compass. With the voices of the sea, the rushing and gurgling of the water under the keel and the singing of the breeze in the rigging, the stars make up the world in which the boat moves, and my thoughts wander.

My sister Alfrun, who is supposed to be sharing the night watch with me, has dropped off to sleep. I sent her to lie down on a bunk that groans with each movement of the catamaran. This endless creaking is a reminder to me that the boat is rather old. Herbert bought it secondhand in Denmark recently. Herbert is Alfrun’s husband, a successful cameraman, passionately fond of the sea. He has lured the whole family, and a friend too, into this adventure, because he is firmly convinced that the boat must be overhauled in the yard where it was built, close to the mouth of the Thames.

Herbert is a born optimist, and with his radiant smile and contagious enthusiasm managed in two days – back home in Salzburg – to involve me completely in this latest venture of his … me a landlubber, who has always been suspicious of anything new … though I had an ancestor from Helgoland.

However, I am happy now. I feel like a real sea-dog, and have completely got over the shock of the Limfjord – where we suddenly found the keel scraping the bottom and had to pull up the centreboards to free ourselves – counting the trip now as one of my ‘happy-ending’ adventures. There is something fascinating about steering a boat – 12 metres long, 8 metres wide, with two masts and two fibreglass hulls, providing living space for four people altogether. You can even sleep on it – if the waves aren’t too big!

As I said, my brother-in-law is very proud of his boat, and yesterday, with the air of an expert, he calculated the meridian using sun and sextant, and with it our course. To us, it seemed like magic, even though we weren’t convinced he’d got it right. After all we were in the middle of the sea. He became a little nervous when we came across some oil-rigs that weren’t on the map, and I suppose I should not have remarked that navigation didn’t usually depend on the location of oil-wells.

Now the cap’n is sleeping, having left instructions to be woken only if we see lights. But there haven’t been any. The masts sway among stars slowly following their courses hour after hour – somehow it is just as when you sit in a bivouac on a clear night, keenly observing their steady circular progress. And, in the same way as the voices of the mountain bring overwhelming tranquillity, so here, the sea speaks to you.

Last year, I found a place where the two came together: rocks and the sea. Foamy crested waves rushed at vertical cliffs like wild stallions. ‘A Dream of White Horses’ is the name given by climbers to a route in Wales where you balance on delicate handholds directly above the crashing sea. Looking down, the frothy water beckons, and not until you have overcome your fear of it can you feel happy.

One English climber there clearly had no qualms. Slim and dark-haired, Julie moved up the rock smoothly, each movement expressing strength and a joy of living, just as an animal in its element expresses itself in movement. Her partner, Dennis, exhibited a similar harmony, white hair and beard, which framed sharp features, blowing wildly in the strong breeze. You could hear the roar of the sea, and the air was bitter with salt.

The two climbed so well together, it was easy to see they were in their element.

I learned later that Dennis was a photographer, specialising in quite stupendous nature pictures. Julie came from East Sussex, where she lived with her husband Terry, a ranger, a man of great strength and serenity. Julie and Terry, besides the forest, looked after their local sandstone rocks and ran climbing courses; they also had a coffee shop for climbers, where the relaxed and friendly Tullis atmosphere reigned supreme. Everybody loved Julie and Terry. It had come to them one day that learning to move on rocks could benefit handicapped children and the blind, and they began organising special courses for them. They never climbed together, perhaps because it made Julie nervous or because it led them to be over-critical of each other’s style on rock.

I met them for the first time when I was on a lecture tour in England many years ago, and again in 1975 when another trip took me to Wales, where Dennis lived. That was when I had seen him and Julie climbing together. The wild sea at the foot of the rocks made a very strong impression on me. Perhaps, by taking part in this boat trip, I wanted to overcome a fear that the unknown element, the fury of the sea, had generated in me. Perhaps I wanted to demonstrate that I was capable of ‘dominating’ something that had dominated me. But demonstrate to whom?

To myself certainly, but perhaps subconsciously also to Julie, whose own fearlessness I found so fascinating. It must have been that, or how else am I to explain to myself all that then followed?

After seeing Julie and Dennis so immersed in their element, I must have had a tentative desire to take part, even to add to the experience something of my own world.

Now, while I hold the helm and glide over the waves, up and down, up and down, I have the same feeling of strength I encountered there. And I even seem to know why I am approaching this coast.

I begin to dream: In the sky, among the stars, between the silhouettes of the sails, I imagine Lohengrin and his swan, and the legend blends into the sounds of the night. To be honest, I don’t remember the story very well, but that doesn’t stop me from elaborating a version of my own, tailored to the circumstances.

I want to go and find her, bring her onto this sea that surrounds her island, if only for a day.

‘The one thing you must never do,’ Herbert had said, ‘is to leave the boat. You never give up!’ The tone of his voice left no doubt how seriously he meant us to take this. Even though we have a canary-yellow dinghy on board, Herbert (who used to be a mountain guide) has fixed a belay line the whole length of the boat, to which he insists we attach ourselves if the sea is rough. We have to do this whenever we are ‘outside’ – that is, outside the two floating hulls. It makes sense, but will we really need it?

Herbert has dreams of a larger boat with all the necessary – and unnecessary – extras for ocean-going. (He will spend years building it – it still isn’t finished yet.)

The storm! Here it is – hissing and whistling, and the boat groaning and squealing …

‘ … It’s not falling apart!’ I cling to the captain’s words, and to the helm.

The storm! In front of me, all I see is a huge wall of grey-green water … it hoists up the little boat, but no sooner are we on top than the next wall appears, and down we plunge towards it … Here comes the wall again … It is never ending … The sea is constantly renewing itself.

The sails vibrate in the whistling air. Everything trembles. Foam flies all around. The old catamaran moans. Each time we ride a wave it seems that the hull must break into a thousand pieces. ‘Just the wood working,’ Herbert declares airily in response to my worried expression. If he says so! We are sharing the helm now. Another wall of water … a valley … a wall … on and on. Not a moment’s rest. Before long we are as stiff as these never-ending, never-yielding walls. ‘Not one of you is to stick his nose outside without first clipping onto the rope with the karabiner,’ Herbert had shouted the minute the storm started. And he explained how impossible it is to find anyone who has fallen overboard in a rough sea. Nobody allowed out without a harness – you can see he was once a mountain guide.

‘Wind force 6!’ he shouts amid the uproar, his blue eyes dancing with excitement. ‘Hey, Kurt … ’ I make no comment. All I hope is it doesn’t go up to 7.

I hold a diagonal course, as instructed, riding the mountains of water, up and down, just like an intrepid skier taking the humps of a rough slope in a straight line. Nobody can keep it up for long, however, and soon we change over. Having completed my stint, I stagger down into one of the hulls to try and find some rest despite the rolling and rocking. Even down there, everything creaks and squeaks, gurgles and snorts … What on earth brings the Walker Spur into my mind all of a sudden, the Grandes Jorasses? Now of all times? It’s a mystery. 1,200 metres of vertical granite, one of the most difficult climbing routes in the western Alps. ‘Well, it’s not as tiring as this,’ I conclude. ‘At least the Spur doesn’t keep moving about.’

I am amazed how well my sister is coping with this turbulent environment. Having a husband like Herbert obviously toughens you up. Gerard, Herbert’s friend, is looking green. ‘It’s the short North Sea waves,’ Herbert comments. ‘You can’t do anything about it.’ It was meant as reassurance. A day has passed and the storm is over. We feel a lot better, but where on earth are we? The last to be at the helm were Alfrun and I, and together we did our best to slice the waves at the right angle. Our poor captain, Herbert, despite himself, is doing battle with seasickness. Gerard, safely over his bout, now that the boat is once more moving peacefully, finds time for a nervous crisis. He has had enough! But you can’t get off a boat in the middle of the ocean, not like on a mountain, where you can simply return to Base Camp. (That’s not true, Kurt – sometimes you have to stick it out even up there!) All three of us try to calm poor Gerard until finally he smiles weakly, it is almost three days since we left the Danish coast. To tell the truth, I feel as if I have made three bivouacs. Nobody has managed to sleep, the best we have had are a few dozing rests. At this point I am convinced that ocean sailing is every bit as hard as a long mountain ascent. At the same time, however, I feel closer to the sea. The sea has become something special for me.

When you are on it, far from land like this, it takes on a different character; you feel in close contact with the water, not a bit like being on the deck of a large ship. It is as if you were absorbed by the essence of the water – the land, the coast, is only a distant, imaginary limit. You cannot appreciate what the sea is until you have experienced it like this.

We catch sight of a few large ships … and feel reassured. At the same time, we worry over the danger of a collision. The automatically piloted giants might never notice a tiny sailing boat. The onus is on us to get ourselves out of the way. And soon we are alone again …

‘Land-ho!’ A coastline has appeared.

Everybody is excited. But where are we?

‘Switch on the Sonar!’ I yell, remembering how we ran aground in the Limfjord.

‘You and your Sonar! I’m amazed you didn’t switch it on in the middle of the North Sea.’ Herbert is sarcastic. He doesn’t like to be reminded of the incident, but how can I help it if I like to know how much sea there is underneath me? ‘The big ships have already shown us where the channel is.’ With conviction, he declares, ‘That’s England ahead.’

‘Oh, really?’ I think to myself, and hazard – ‘couldn’t it be the Dutch coast?’

‘For Heaven’s sake, Kurt!’ Herbert shuts me up with a ferocious glance and I mutter something about the unpredictability of marine currents. But he’s right. It must be the English coast. Only where?

‘We must wait until night,’ says Herbert when we are a few kilometres off shore. We can just make out houses and trees; we drop anchor.

But why? Why wait until night-time? In the darkness you can see lighthouses and lightships, each with its own special signal. If we count the seconds between one impulse and the next, and look up the frequency on a chart we have on board, we can work out our location exactly.

Simple! However, when darkness falls the colour of the signals from the first lighthouse does not correspond with the chart, only the intervals do.

‘Perhaps the lighthouse-keeper screwed in a red bulb when the last one burned out. Maybe he didn’t have another white one.’ That’s my simplistic explanation. One thing is sure – and another of the lighthouses confirmed it, we are lying off the English coast, to the east of the Thames estuary.

London, Saint Katharine’s Dock, Tower Bridge. We have sailed up the Thames.

Alfrun and Gerard go home – overland. Herbert and I stay a few days until everything is ready for the Swan’s refit. Lohengrin Mark II – that’s me – goes to make a phone call to Terry and Julie …

Will she say ‘yes’? She hardly knows me, after all, and she doesn’t know Herbert at all. Two Austrian mountain guides and film-makers. Are these trustworthy professions in the eyes of an Englishwoman? Or will we seem more like buccaneers to her? The only thing I want to do is to repay her for those wonderful days climbing in Wales by inviting her to come sailing with us, so that she can see how marvellous it is to dance on the waves in a catamaran. Maybe we’ll even go as far as the French coast. For the weekend. It’s all right with Herbert – but what about Julie?

Kurt, I tell myself, stop all this Swan nonsense. Who knows how the story of Lohengrin really turned out? On the phone, my nerve fails me. I pose the question finally when we meet – in the middle of Terry’s birthday celebrations – and Julie turns down the proposition. But I’m not convinced. Next day we go climbing on a sandstone outcrop in the Sussex woods and I make another attempt, ‘Why don’t we sail across to France?’

You can sense whether or not a person possesses an adventurous spirit: there is some kind of special emanation – and Julie had this. I could feel very strongly that she was a born explorer. I believe she had the courage and the desire to try almost anything. Often, she felt obliged to stay quietly at home because of her family, but not always. Suddenly, she’d be off! She would run through the woods, climb her rocks, or dash up to Wales to climb with Dennis, or be on her way to some other place. Terry was understanding. He’d long got used to it, he said. So it didn’t seem strange to me to be making a suggestion like this. But I was nervous. Shouldn’t I have been? Sail in a catamaran to the French coast? Could I still convince her?

She looked at me thoughtfully. The air seemed to be vibrating, in small waves, dissolving into thousands of tiny dancing points, and I was sure that she wanted to come. In that moment she was on the boat and – I don’t know why – I was held spellbound by her dark eyes. For several seconds I was incapable of thought, overcome by an emotion I could not recognise. Our gaze almost froze, and I felt sure that her voice could only say ‘yes’. When she slowly opened her lips there was consent in her eyes, along with a shyness and reserve, as well as something else I did not recognise, something foreign …

‘It’s not possible,’ I heard her say. ‘I have to go to see Dennis. He’s ill.’ She looked up at the gently swaying trees. Her climbing partner had angina, she explained, and she had promised to visit him. I knew from when we were in Wales how close they were to one another.

Timidly at first, then with increasing insistence, I pointed out that it would not take long to sail across to France. It was an opportunity that would not come again. Herbert was about to take the boat to the Mediterranean. I so much wanted to show her my ‘ocean’, the ocean I had just lived with. I could still feel the blue-green waves within me … and I sensed how much Julie longed for this adventure. It had to be! But she said ‘no’, and that was that. Even Terry’s encouragement served no purpose.

Much later she told me that her loyalty to Dennis was not the sole reason for refusing. She had a deep feeling – call it intuition – that this was not the right moment for us to get to know each other better.

I left, upset and disappointed. We didn’t see each other again for three years.

Then, quite by chance, we bumped into one another in a restaurant at the Trento Film Festival. Julie was with Terry, and I with Teresa and our small son Ceci. We were even staying in the same hotel, we discovered, in adjacent rooms! Even now I find that hard to believe. Neither of us had been to a festival for years, and we had heard nothing of each other …

Yet there we were, as if the stars had cast the dice.

And nothing had changed; we realised it right away. It was as if I had left England only the day before.

Yet, there was something different.

‘I would go on the boat now!’ Julie ventured.

‘Let’s go and climb the Alps,’ I said.

The Alps turned into the Himalayas. It was the beginning of our adventures.

… Even the Himalayas were born of the ocean.

Dream Mountain – K2 from the North

Floodwaters – Sinkiang on Camelback

Floodwaters in the high Shaksgam valley: the sky is filled with tumult, a continuous agitation that dominates everything … the very air seems to tremble. My camel leans his full weight against the rushing current. Spume flies everywhere, and the deafening roar of the swollen Kaladjin river drowns out all other sound. I can feel the animal testing the sandy bottom with its feet, looking for hidden holes gouged by the power of the swirling floods.

Floodwaters – elemental, like an avalanche. You are impotent, completely at their mercy if the waters rise further. It’s not like a storm on a mountain – then you can grasp what’s happening. Here there is just fear … you listen to the roar and ask yourself all the time whether it’s getting louder. It is as if somewhere above you, out of sight, tons of snow have broken off and begun rolling towards you – you hear it coming without knowing if or when it will engulf you.

Do Sinkiang camels have a sixth sense, I wonder? My animal seems totally calm as it leans into the water methodically prodding the river bed, moving, stopping, moving on. Just trust the camel, Kurt …

The Shaksgam Valley. Here, in its lower section, we are at 4,000 metres: the deep furrow cuts across uninhabited country, some of the most inaccessible on earth, a region of glaciers and high mountain desert. From one end to the other, the valley is about 200 kilometres, and nobody has ever covered its entire distance. Higher up, immense rivers of ice block it from side to side like giant dams. We have to leave it before we reach these, but now it offers the only possible route. For almost two months, practically the whole summer, any passage has been impossible because of the rushing meltwater coming down from the mountains and glaciers. Even now, at the end of August, the kilometre-wide valley floor is a close network of streams and islands, contained within the pale faces of the Kun Lun and the wild Karakoram mountains. For days we have been zigzagging our way through this huge, sinister valley.

How often will we have to re-cross the waters, fight this current? Twenty times? Thirty times? In my memory I see the clear, shallow stream – marvellously pure spring water … good to drink – that appeared so unexpectedly out of the interminable, barren gravels of the valley floor during the dry season last May when we were on our way in to K2. Now it is a tangle of glittering, tightly entwined loops, a confusion of meanders and bursting banks, one overlaying another, changing pattern from hour to hour in response to the sun’s radiation or the clouds in the sky – and who knows what is happening fifty kilometres upstream? These braided serpents have control of the whole valley floor and hemmed in by the prohibitively steep walls on either side, their brittle rocks torn by heat, we are allowed no escape. There is only one way out: the Shaksgam.

My animal moves forward slowly, up to its belly in the foaming, brown water, the prow wave from its throat carried away by the current so that for some moments it seems we are speeding rapidly upriver, faster than the wind – an optical illusion that has already caused several of us to lose our equilibrium when trying to ‘counterbalance’ it. I cling to the ropes in the camel’s thick fur, arched, tense, ready if the animal should suddenly stumble to throw my weight in whatever direction might be required. A half-strangled cry makes me look round and I’m horrified to see Rodolfo and Giorgio disappearing into the silty waters. Between them, their camel’s head rides the surface. The beast was pulled off its legs by the force of the torrent. With frightening speed, my friends are carried downstream towards a vertical rock wall. Nobody can help them. I see them appear and disappear, paddling desperately with their arms. Just before the river smashes into the wall they manage to catch hold of some rocks on the bank. The camel, with its longer legs, had got out earlier. Certainly, without these incredibly resilient, near-indestructible beasts, we would have no hope of making it out of this mountain desert on the Chinese side of K2. Even so, yesterday four loads were lost in the river, and today three. We must be thankful nobody has drowned – there have been plenty of opportunities. The wild torrents of the Himalayas and Karakoram have claimed the lives of so many climbers over the years.

Right now, none of us wants to know about mountain summits – we are a worn out, dissolute crew, scorched in our minds after four months in the high Sinkiang desert. Our only thoughts are for home. This desperate longing drives us to plunge again and again into the muddy waters of the river which stands between us and our return – from stream to stream we go, island to island, day to day … One of us has special cause to be afraid, little Agostino, our first summiteer on K2: he doesn’t know how to swim! But without exception, all twenty-two members of this international (but mainly Italian) expedition have had their fill of the Shaksgam waters. Our bodies bear witness to the rigours of the past months on the mountain – rugged faces and baggy clothes flapping wraithlike around spindly limbs. One person has lost 15 kilos, another 20, and I am a full 23 kilos lighter. Julie, our British member who helped me with the filming up to 8,000 metres, has only shed 10 kilos, but however much she might have longed to be slim, she wouldn’t win any beauty contests now, any more than would Christina, our doctor. Still, when you have been together on a mountain for so long, gone through so much, coped with all the disappointments, fears and joys, things like appearance matter very little. Helpfulness is so much more important.

Regardless of what she looks like, Julie has lost none of her energy and strength, nor the resilience that I so much admire. It’s true her skin is a collection of wrinkles … but the eyes in the thin, burned face are unchanged; and it’s what’s in them that counts. Sometimes, a fleeting, quiet smile lights her face, and under her tangled hair the eyes shine like the shimmer of mountain ice.

What we have brought back from one of the loneliest places on earth is happiness.

Our expedition team forged bonds of friendship, even if this was one of the toughest and longest enterprises I have ever been engaged in. Maybe, because of that.