10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

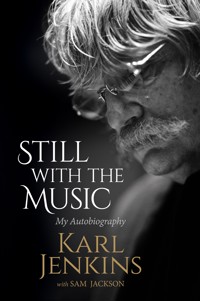

Music is a language that speaks to us all. But the music of Sir Karl Jenkins transcends boundaries of style and genre, of geography, language and nationality to communicate a message of peace that has profoundly moved millions around the world.Incorporating diverse influences from religious and historical texts, multicultural musical styles and, famously, a vocalised language of sounds that speaks directly to the heart, Karl has written powerful works such as Adiemus; and the iconic The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace; that encompass the depth and breadth of human emotion.From a modest upbringing in Penclawdd, Wales, steeped in the Welsh choral tradition and the Western classical canon, Karl followed his love of music to London, immersing himself in the 1960s jazz world of Ronnie Scott's, before joining the seminal prog-rock group Soft Machine. These diverse influences made him one of the most successful composers in the dynamic advertising industry of the 1980s, ultimately leading to his landmark Adiemus project in the 1990s, which inspired him to create the works that have now moved so many.As Karl says, "we all work with the same twelve notes'. Still with the Music is the story of how those twelve notes became something magical, a celebration of the power of music to bring joy, to inspire and to heal. Sir Karl Jenkins is that rare thing: a contemporary classical composer with enormous popular appeal, and one of Britain's national treasures.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 410

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

For my family:Carol, Jody, Rosie, Astrid and Minty and in memory of those departed

CONTENTS

1. Beginnings

2. The Teenage Years

3. Beyond Penclawdd

4. The Lure of London

5. Soft Machine

6. The Advertising Years

7. Briarwood

8. Adiemus

9. The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace

10. Celts, Ballet and the East

11. The Studio

12. Vocalise

13. Stembridge Mill

14. The Concertos

15. Beyond the Concertos

16. The Peacemakers

17. Reflections

18. Seventy

Discography

Acknowledgements

Index

A few years ago now, I was visiting Swansea market, happily wrapped up in a world of my own. Suddenly, my daydreaming was interrupted when, out of nowhere, one of the very Welsh cockle-vendors from my home village of Penclawdd shouted, ‘Kaaarl! Still with the mew-sic?’

1

BEGINNINGS

Many people have careers in music, but not so many have what amounts to four – four consecutive careers, spanning fifty years, using the same twelve notes. It took me many years as a musical tourist to discover what I was good at. I arrived at my natural musical habitat with Adiemus, The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace and the works that followed. I seem to have made such a significant connection, through my music, with people from all over the globe that I thought it might justify my writing this book. The getting there is not without interest, too, and is, of course, the path that led me to where I am now.

One day in May 2015, on returning to London from some concerts in Kazakhstan, I went to our studio to see my son and collect the company mail. There was a letter from the Cabinet Office. It read:

The Prime Minister has asked me to inform you that having accepted the advice of the Head of the Civil Service and the Main Honours Committee, he proposes to submit your name to the Queen. He is recommending that Her Majesty be graciously pleased to approve that the honour of Knighthood be conferred upon you in the Birthday 2015 Honours List.

However, my beginnings were far more humble. I was born in Neath, South Wales, on 17 February 1944. My childhood was full of love and laughter, but recently it’s dawned on me that before I was even out of my teens, I had experienced more tragedy in the first few years of my life than most of my contemporaries would experience in their first few decades. This is something I’ll return to in the pages that follow. For now, though, allow me to share what it was like growing up in this beautiful part of Wales in the 1940s and 1950s.

The Jenkins family had made its home in the coastal village of Penclawdd, nestling between an imposing hill (known as the Graig) on the one side and the Bury estuary, on the stunning Gower Peninsula, on the other – a location that later gained some status as the first place in the United Kingdom to be officially designated an area of outstanding natural beauty. I was the first and only child of my parents, David and Lily. Although I might not have had a very large nuclear family, I vividly remember being surrounded by many aunts, uncles and close friends in this tight-knit community.

Penclawdd was, and is, famous for its cockles. They were collected ‘out on the sands’, when the tide had receded, and brought back in sacks to the factories, either by horse-drawn cart or by donkey. Most cockle-pickers were women, and many balanced the sieves, used for riddling the cockles, on their heads. Seeing them walk through the village, with their donkeys loaded with sacks of cockles beside them, was quite an alien sight for a British community. An ancillary task was the collection of seaweed of the laver variety – Porphyra umbilicalis – to make laverbread.

At one time, Penclawdd had been a thriving industrial village with a tin works. It also had a dock and ships that used to ‘to and fro’ from Cornwall, taking coal from the pits nearby and bringing back tin for processing. This modest village had seven pubs on the estuary front (all within the space of a mile), three Nonconformist chapels and one church. By the time I arrived, only three pubs had survived, but the chapels and church remain to this day.

One of the pubs that had fallen into disuse, the New Inn, had been converted into the cottage home of my mother’s parents. Around a decade before I was born, my grandmother had died when, along with eight other cocklewomen, she drowned on the sands in the Bury estuary. The sudden death of a family member, especially in such horrendous circumstances, is something that can never be forgotten. Many of my relatives were still living with their deep loss at the time of my birth.

In happier times, my maternal grandmother – Margaret Ann – used to go by train to the bigger towns further east every Saturday to sell cockles. In Newport, she met a Swedish sailor – one Carl Gustavus Edward Pamp. He was smitten with her, and she with him. They eventually married and settled in Penclawdd, raising three children: Axel, Ida and Lily. My grandfather was always known to me as Morfar, which is Swedish for ‘mother’s father’. Swedes sensibly have a different name for each grandparent. Morfar was a real character, and often used to stand on the ‘ship bank’ and sway, as if he were riding the rolling sea. Back in Sweden, his three sisters owned a ladies’ clothes shop in Gävle, north of Stockholm. Their grandfather, Lars, had been Head Gardener to the King of Sweden, and their brother Axel a ship’s captain who had gone down with his ship.

I remember an occasion when Morfar’s sisters, none of whom had married, came to visit from Sweden. He retired early one night, which was very unlike him. The sisters sent my cousin upstairs to see if he was all right but he wasn’t there. Morfar had gone out through the window, down a ladder, and over to the Ship and Castle pub. He certainly liked a drink. He was also a hoarder: on one occasion I needed some empty matchboxes for a project at junior school and he gave me fifty.

One of the earliest memories I have of my contented childhood is of the little car Morfar, who was extremely clever with his hands, made for me. I can still feel the thrill of being able to sit in this bright red car, steer it and pedal along. Somehow it had acquired a Wolseley badge on the bonnet. I was in awe of Morfar’s many talents, which even extended to the skilful pickling of a multitude of vegetables. We never went short of pickled gherkins in our family.

The other side of the family was 100 per cent Welsh. As was the case with my mother’s relatives, they too had faced tragedy before I was born. My grandfather, William Jenkins, was killed underground when a colliery wall fell on him. He was survived by my grandmother, Mary Ann, and their five children: Thomas Charles (who died very young); my aunt Evelyn Mary; Alfryn James, who was lost over Berlin as a Lancaster bomber pilot with an all-Welsh crew in 1944; William Ivor; and my father, Joseph David, who was often known simply as Dai or Dai Bach (‘Little David’).

The house where I began life was called Min-Y-Dwr, meaning ‘edge of the water’; unsurprisingly, it was on the estuary front. Despite being named after my grandfather, I was always Karl with a ‘K’ – not for any profound reason, it turns out, but simply because my parents preferred the spelling. As far as I know, our existence as a little family of three was initially a simple but very happy one. However, soon after I was born, my mother contracted tuberculosis and her health began to deteriorate. I later learned that, sadly, she had initially been misdiagnosed. When I was aged two, it was decided that she and I should go and live in Sweden for a while, where it was thought the air might benefit her. My father, a schoolteacher, stayed behind in Wales and came out to join us only during school holidays. Despite being just two years old at the time, I can remember flying out from Northolt in a Dakota aircraft. The first sounds I uttered were Swedish, which my mother spoke fluently; alas, all gone now. Her health did not improve, so we returned. My mother died before I was five.

While I will always be able to recall my father’s warmth and compassion, any knowledge of my mother is based largely on what others have told me. What I do remember, though, is how confused I was at the time of her passing. Emotions weren’t really talked about in those days; I don’t believe this was something particular to Wales, but more a question of what was deemed appropriate in the late 1940s. When my mother died, I was staying with my aunt Ida and uncle Cliff. As they put me to bed one night, I looked at my uncle and simply asked, ‘Where’s Mammy?’ His response was short and to the point: ‘She’s in heaven.’ No one had yet told me my mother had died and I had no real idea of what heaven was. I was just four years old, staying in a house that wasn’t my home. The first I knew of my mother not being there for me any more was when Uncle Cliff made this brief, unexplained comment. In retrospect, it seems a very callous and stupid thing to say to a four-year-old, even though I realise it was not deliberate but probably uttered in panic.

Astonishing as it may seem nowadays, after that point I was largely left on my own to deal with any grief I may have felt. I was taken on the six-mile journey home to Penclawdd; I didn’t attend my mother’s funeral, and nothing was ever explained. Nowadays, people talk of the importance of reaching ‘closure’ after any kind of trauma but in the 1940s that was a wholly alien concept. I didn’t find the traditional mourning process to be helpful at all: seeing friends and relatives wearing black for days on end only prolonged my sadness and, I suppose, prevented me from being able to move on from that dark time in my young life.

My abiding memory of this entire period, beyond feeling confusion over why my mother was no longer there, was of our new home. My father and I moved out of the house we had lived in as a family of three, swapping places with Ivor and his wife Llewella, and taking up residence with my grandmother and aunt, so that the two women could look after us. Benson Cottage became the place I would call home from the age of five until I left Penclawdd for university. Despite the sadness of family bereavement, I had a wonderfully carefree childhood with my dad, our cat Sparky, our budgie Kiki, my Aunty Ev and my mam – short for mamgu, Welsh for ‘grandmother’. It was by no means a stoic existence: within the confines of society at the time, our family was very open and warm. There were many women in my life, all of whom felt sorry for me as an only child with no mother – and all of whom I called ‘aunty’, even when they were not related to me. Aunty ’Fanw (Myfanwy), for example: she lived next door and she’s still there, aged ninety-seven.

My father, born and raised in the village, went to Gowerton Boys’ Grammar School, three miles up the road, which I also attended many years later. He went on to Caerleon College, near Newport, where he trained to be a teacher. Everyone tells me that he was an outstanding rugby player. He played as a stand-off half for the ‘All Whites’ (Swansea) while still at school. Mam once told me how he returned home one Boxing Day in a sorry state, having broken his collarbone in a match against London Welsh on their annual tour of the principality. My father could also, reputedly, clear his own height in the high jump – but then he was not very tall. I did see him play cricket for Penclawdd though, on the ‘Rec’.

My father was to be the greatest influence in my life, both personally and musically. He was multi-talented: a photographer who ‘did weddings’ at weekends, a teacher of art and pottery, a producer of school plays, but above all he was a musician. His instruments were the piano, which he also taught, and the organ.

It has been suggested to me that I must have inherited my father’s creativity; and if these things are indeed genetic, then this could be the case. But my dad had a far wider skill set than I have. Whereas my interests have always by and large been confined to music, he had the most extraordinarily broad range of hobbies, and a real desire for knowledge, too. His creative thirst was all expressed at an amateur, local level, but it was none the poorer for that. I’m proud of the fact that my father was respected and revered by a great many people. Even nowadays, former pupils of his come up to me to say what a great teacher he was. It’s a wonderful thing to hear.

When my father went to the chapel to practise the organ, I often went with him. As my musical confidence grew, having started piano with him, I would sometimes play a little myself but generally I went simply to listen. My father’s passion was the music of Bach.

Many family groups had nicknames. Ours was ‘the Baswrs’, an anglicised plural of the Welsh word baswr, meaning ‘bass’, due to a preponderance of good male singing voices in the extended family.

The link between religion and society in my little part of South Wales was very strong, and its importance should not be underestimated. Everyone attended one of the chapels and there was often quite fierce yet ultimately trivial rivalry between the different congregations. My family was very Christian, in the traditional sense: they were Nonconformist Methodists who followed the rules. They would wear their Sunday best, without fail, and alcohol would virtually never pass their lips – the only exception being a cheeky sherry at Christmas. They all had a living faith as well, though; it wasn’t only about rules and regulations. My father was very devout: I used to ask him sometimes, later in life, why he had never remarried, but he was always of the firm belief that he would see my mother again, in ‘the afterlife’.

There were two musical Jenkins families in the village and in our chapel. There was my father and I, and there was the family descended from William Jenkins ‘Pen y Lan’, the sobriquet deriving from the ‘top of shore’ area where he lived. My father eventually succeeded William’s nephew Gwynfor as choirmaster and organist, the position becoming vacant on the death of the incumbent.

The two families did intermarry at one point when William Jenkins’s niece Gwen married my uncle Alfryn, who had played the viola. When I composed For the Fallen, which takes as its text the Laurence Binyon poem, for the 2010 Festival of Remembrance at the Royal Albert Hall, I dedicated the piece to Alfryn, the pilot who had died in the Second World War. It begins with a viola solo in homage to him.

Some of my musical education came through Tabernacle Calvinistic Methodist Chapel. We would go there three times every Sunday, and the place had a very profound impact on me. As for the rest of my studies, I had an extremely positive experience of school, beginning at Penclawdd Infants. I sat next to John Ratti, whose father Ernesto (known by the more prosaic name of Ernie) was one of the many Italians who had come to South Wales and opened cafes, or betting shops. In his cafe Ernie used to serve what the locals called ‘frothy coffee’, which was, of course, cappuccino. He had a massive Gaggia coffee machine and he also made exceptionally good ice-cream. In common with the other Italians and Germans already living in the United Kingdom, Ernie had been interned during the war. I can recall Gwynfor Jenkins bringing tears to this lovely man’s eyes by intoning parts of the Latin Mass to him in Ratti’s Café.

Penclawdd Infants was followed by Penclawdd Junior, where I still sat next to John Ratti. We used to take the bus through the village to the ‘west end’ where the school stood. The bus stop was outside ‘Morgans the Forge’ and the blacksmith would often be shoeing the cockle and farm horses there in the morning. I can still smell the sizzling moment when he placed the red-hot shoe on the animal’s hoof and see the resulting cloud of smoke.

John Ratti always was a joker. His father’s cafe had a window display of confectionery including Cadbury’s chocolates. To avoid them melting in the sunshine, they had cardboard innards. One April Fools’ Day John happily gave them to the teachers.

The headmaster at junior school was the same Gwynfor Jenkins. He had a useful sideline in hot weather making ice cubes on a stick and selling them for a penny (an ‘old penny’, of course, with 240 to a pound). Gwynfor was a good musician and introduced us to the tonic sol-fa technique for sight singing: do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, do.

As a child, I took part in Cymanfa Ganu (congregational singing festivals) and was exposed to that raw style of four-part hymn singing that definitely was to be a lasting influence on me. The local community took these festivals seriously, and that attitude was infectious. People often say that Wales is a musical nation and, to a certain degree, it is; but it’s really only singing that the Welsh like. I doubt that the knowledge of classical music in Wales is particularly extensive, at least no more so than anywhere else, but it’s certainly true that the Welsh are a cut above the rest of the UK when it comes to the ability to sing in four-part harmony.

At chapel, there was also the annual oratorio concert when the choir would perform a work such as Handel’s Messiah or Mendelssohn’s Elijah. These were not, by any means, parochial affairs. The Morgan Lloyd Orchestra was hired and soloists often came from London. (Morgan, once a prodigy, had studied at the Royal Academy of Music, where I was later to go.) As young artists some now-famous names including Dame Janet Baker, Raimund Herincx, Philip Langridge and Heather Harper appeared, and much later, after I had left, a young baritone named Bryn Terfel Jones.

When my father became organist and choirmaster, he transcribed the whole of Fauré’s Requiem into tonic sol-fa for the choir since this was the only system they could read, not the ‘old notation’, as what we generally know to be printed music was called.

It was quite a vibrant tradition. The other big chapel, Bethel, performed annual oratorios as well and, for these occasions, choirs used to join together to swell the numbers, setting their customary tribal rivalry aside. Oratorios were known as ‘books’, so a question might be asked about a conductor: ‘What book is David taking next year?’ There was even an ‘oratorio of the oratorios’ called Comforting Words, consisting of the most popular movements from a selection of them. Whether the libretto made any sense I do not know.

A once local ‘girl’ sometimes featured in these oratorio performances: Maureen Guy, the daughter of a coal miner, who had attended Bethel Chapel, Gowerton Girls’ Grammar School and the Guildhall School of Music. She had become a mezzo-soprano of distinction, singing at Stravinsky’s eightieth birthday celebrations, with the composer conducting his Oedipus Rex. She is also one of the Rhinemaidens on Georg Solti’s iconic 1960s recording of Wagner’s Ring Cycle. My father took their wedding photographs when she married, at Bethel Chapel, the tenor John Mitchinson. She died in 2015.

Growing up in Penclawdd, there were so many characters in the village, many with nicknames: there was ‘Dai Kick’ (the rugby standoff half who would never pass the ball); ‘Mrs America’ (she’d been there once); ‘Paris Fashions’ (she liked to dress well); ‘Selwyn Flat Roof’ (his house had one); ‘Jumper’ (as a boy I was told it was because he was good at the long jump, but later learned it was because he had twenty children). Then there was Ivor Rees the cobbler, who had only one hand, and at the Memorial Hall cinema there was ‘usherette’ Sergeant Lord, a retired policeman, whose role was not to show customers to their seat but to shine his torch in people’s faces to stop them talking or throwing sweet wrappers at the screen.

My father’s cousin, Griff Griffiths, was both barber and undertaker, leading to inevitable comparisons with Sweeney Todd. We had a Dai Bun (a baker) and a Dai Brush (a painter and decorator), Morgan Morgans known as ‘Morgans Twice’, Willie Jones ‘the French’ (he saw action there in the First World War), ‘Leonard the Coal’ and ‘Gwyn the Milk’.

When Gwyn the Milk did the rounds for his customary free Christmas drink, it was the only time in the year that he took off his cap. His bald head was two shades: a dark weather-beaten face with a snow-white pate. He used to deliver his milk with Tommy the horse and a cart, with his dog Peter in tow. I remember when his milk was delivered in churns and dispensed by a jug; after all, this was a time when farmers like Gwyn actually milked their own cows and sold their own milk. When pasteurisation came in, Gwyn always insisted that the bottled milk he got back from the dairy was his very own. He had such a long milk round and such a slow method of delivery that we always had our milk in the afternoon – and, in summer, very warm milk it was too.

Perhaps my favourite character of all is Will Hopkins, who played the double-bass. His nephew, Glynn Rees, was responsible for the first television set I ever saw. Glynn worked in London for one of the early television manufacturers, and he assembled a set for his uncle. Being hard of hearing, Will used an enormous ear trumpet. He had his favourite chair and he would not budge from it. Because of the way the aerial had to be positioned, the television set would work only in a certain part of the room. For many years, Will, with his ear trumpet, watched television in the mirror hanging on the opposite wall. I wonder if it affected how he saw certain aspects of life.

Life at school, meanwhile, carried on. I used to walk the mile home but often my father, having finished his day teaching at around the same time, would collect me on his bike, which had a child seat fixed on the crossbar. For the last year or so at junior school, I was in the eleven-plus ‘scholarship class’ and too big for the crossbar. This class was not selective. Some families didn’t want their offspring even to attempt to gain a place at the grammar school. They would go on to Penclawdd Secondary Modern and leave to work at fourteen.

Our teacher, Ivor Davies, was a very strict disciplinarian of the old school and a bachelor, brandishing a cane that he was not loath to use. He sometimes took us outside for ‘physical jerks’, exercising in the schoolyard, still wearing his blue serge suit and trilby, and flexing his cane. He was also well known in the area for delivering dramatic Victorian monologues such as Kipling’s ‘You’re a Better Man Than I Am, Gunga Din’.

My best friends out of school were the brothers Jeff and Brent Rees. Jeff was older than me and Brent was younger. The orchard of their garden backed onto Benson Cottage and we spent hours in this magical place. One winter we built an igloo. We compacted snow quite thickly in a circle and placed some corrugated tin sheets over the top to serve as the base of a roof before covering that with more snow. It was still standing in April, long after the snows had gone. We also constructed a tree house with some planks and rope. It was probably not very safe but we had enormous fun. Sadly, Jeff perished in a motor accident in his early twenties and Brent took his own life not long after. I sometimes spent time with two other brothers, Geoffrey and Ian Nichols, who also lived in Benson Street. In a bizarre coincidence, Ian, while still a young man, was also killed on the road, in a motorcycle accident.

I recall playing cricket in Benson Street, the wicket being drawn on the door of ‘Uncle’ Haydn’s garage. The Christian names Haydn and Handel were quite common in Wales at that time, no doubt taken from the composers of the popular oratorios The Creation and Messiah.

I had also joined the Boy Scouts, which met in Dunvant, a village some five miles away. Six of us used to travel, by bus once a week, from Penclawdd, to learn skills such as semaphore signalling, Morse code, first aid, and igniting a fire without matches to make ‘twist’ (cooking dough wrapped around a stick). How useful those skills were in the 20th century was somewhat questionable but it was immense fun and I did gain my Scouts ‘Musician’ badge as well. What I did not enjoy, however, were the feelings of homesickness that pervaded at this time. I remember the very first occasion I really missed home: our Boy Scouts troop went camping in Oxwich, a beautiful bay in South Gower. The feeling of loneliness and isolation at that time was all encompassing; around that point, I was always worrying about my loved ones if they weren’t with me, feelings that persist to this day, undoubtedly stemming from the loss of my mother.

Two other friends from those days at school were Spencer Howells, the son of the chapel caretaker, and Gillian Matthews. Spencer went on to have a blistering academic career, with periods of study at both Cambridge and Oxford Universities, before becoming a research scientist.

I was determined to have someone accompany me when I began exploring jazz at the piano, so I removed the strings from an old banjo and converted it into a side drum so that Spencer could play along after chapel on Sunday nights. The banjo has a skin-headed soundbox, just like a drum. We had a defunct TV aerial, so I cut out two pieces of the thin hollow aluminium tubes into which I hammered some bristles from a brush, thus producing a pair of ‘jazz brushes’. Spencer later bought a snare drum. Much later I was best man at his wedding.

Gillian (my first ‘girlfriend’, when we were six) eventually married Tony Small, who is now a very close friend of mine. He is a fine trumpeter who was destined to stay two years ahead of me at the same five academic institutions, from Penclawdd Infants and Junior Schools, through Gowerton Grammar and Cardiff University to the Royal Academy of Music in London.

All the way through my youth, I enjoyed playing the piano, my father having taught me from the age of six, but I was never more than adequate, despite passing some early Associated Board examinations with distinction. Having a parent as a teacher is not necessarily a good idea, since there is an inevitable familiarity there that somehow compromises the pupil–teacher relationship; what’s more, I hadn’t yet found my ‘real’ instrument, the one that would perfectly suit me.

Because I had started school early, I had two attempts at the eleven-plus scholarship, passing the second time, and in September 1956 I began at Gowerton Boys’ Grammar School. I might have been at a new school, but some things remained reassuringly the same. Happily, I was still sitting next to John Ratti.

2

THE TEENAGE YEARS

DDuring the late 1950s and early 1960s, my days were punctuated with the three-mile bus journey from Penclawdd to Gowerton Boys’ Grammar School. It was a place of academic, sporting and musical achievement and excellence, with a catchment area covering the whole of the Gower Peninsula, together with some other villages towards Swansea in the east and Loughor Bridge in the west. Loughor Bridge was the gateway to Carmarthen and west Wales; at one time, it was very busy on Sundays since on the Glamorgan side the pubs were open and on the Carmarthen side they were not.

There were about sixty boys in the annual intake, divided into two forms. I later came to love it there, but at first I found it extremely difficult to cope with the new surroundings. I started to develop a stammer, and I felt paralysed by it. Reading aloud in class was torture. I was always looking ahead to calculate what passage would come my way and what letter the text would start with. Ws were horrendous; As OK. It took two years for the stammer to disappear. In the context of a lifetime, I realise that’s not very long, but it always caused me great anguish.

Some other issues also surfaced during this pre-pubescent period, without doubt caused by the same demon I was subconsciously dealing with: the death of my mother. I was prone to blushing and when discussions took place, whether formal or informal, regarding one’s mother, as inevitably surfaced occasionally, my stomach churned and I felt like crawling into a hole. I somehow felt ashamed – not a healthy consequence. I suppose I’ve been introverted and taciturn ever since.

I was homesick, which in retrospect seems an absurd thing to say since we were all, as grammar school boys, day students. I even had family to hand in that my Aunty Ev, who had raised me with my grandmother and my father since my mother had died, was working in the school kitchen as a cook.

Over time, though, the issue receded. I lost my stammer and I began to appreciate what was on offer at Gowerton – and beyond. Aunty Ev had very much become my surrogate mother; and I, her surrogate son. She had been widowed in the 1930s and had no children. A wonderfully warm and caring woman, she was extremely popular. She also had a good soprano voice and sung both in the chapel choir and in the mixed choir that had started in the village and of which my father was the accompanist. At Christmas lunch in Gowerton School, Aunty Ev used to dress up as Santa and give the embarrassed all-male staff, sitting at the head table, a gift and a kiss.

She was quite a character. Many years later, Jody, my son, and I were about to sit down with her to watch, on television, a rugby international involving Wales. She was then well into her eighties and soon began dozing off in her chair. She suddenly opened one eye and said, ‘Wake me up if there’s a fight!’

Morfar had died when I was ten, and my Swedish great aunts, Lily, Hilda and Mia, were to leave this world during my teenage years and shortly beyond. So I went over to Sweden to attend three separate funerals during the next ten years or so. The eldest, Lily, the only one with any real English, went first. They all lived well into their nineties but none of them married, leaving me bereft of any Swedish relatives, and of the possibility of becoming bilingual, which never developed beyond fledgling status.

I should mention the question of language in Wales. It was pretty much a lottery as to whether one was Welsh-speaking or not. If a child came from a Welsh-speaking family, it was almost certain that the offspring would speak some Welsh as well. To what extent often depended on whether or not Welsh was the first language of one of the parents. Some families spoke only English; some, only Welsh; and others mixed them up, using both. One could almost draw a diagonal line across Gower from Llanmadoc (at the northern end of the iconic three-mile Rhossili Bay) in the north-west, to Swansea in the south-east. South of that line was a land of agriculture and farming with sandy beaches, dramatic cliff scenery, coastal caves – and virtually no Welsh spoken. North of that line was an area of salty marshes and with an industrial past where Welsh was spoken, but not universally. Incredibly, many celebrated English-language actors came from a relatively small area around Swansea: Richard Burton, Ray Milland, Anthony Hopkins, Siân Phillips, Michael Sheen, Catherine Zeta Jones and, of course, the poet Dylan Thomas, who wrote in English. Neither I nor any of my friends spoke Welsh. My father could, to a certain extent, but no one else in the family was even close to being bilingual, let alone trilingual. Whether my Swedish-speaking mother spoke some Welsh, I don’t know.

I came from a generation where learning Welsh was neither actively encouraged nor compulsory in schools. There was even a school of thought, which had some currency at the time, that speaking Welsh could ‘hold one back’. This sentiment, I should add, was not universally held but the general perception was that English was the language of opportunity and the future.

I therefore took French and Latin for O level, instead of what some would consider should have been my mother tongue. The situation has since changed, with the Welsh language becoming compulsory in schools. Today, most young people in the principality are indeed bilingual, with some schools teaching all subjects through the medium of Welsh. Indeed, the actual building I attended is now such a Welsh school. Wales is officially a bilingual country and I regret not learning the language.

Today, I associate Gowerton School with so many happy memories. The music department was, quite simply, amazing. Sadly, it puts what is available nowadays in schools to shame and is an indictment of what has happened to music education in this country. The music teacher was C.K. (Cynwyd King) Watkins, and many fine musicians went through his hands. Alun Hoddinott, the composer, was one such. Hoddinott taught me composition and orchestration at Cardiff University, where he was a lecturer and, later, head of department.

Early class music lessons at Gowerton were relatively basic and general – more like music appreciation – since all boys took the subject, but once one decided to study music at O level, that all changed. Lessons then entailed harmony, some counterpoint, aural training, music history, form and analysis. Astonishing as it may seem in today’s relatively impoverished educational world, every orchestral instrument was on offer, with tuition provided by expert peripatetic teachers. Moreover, both the use of the instrument and the lessons were completely free of charge. Of course, if a child showed a degree of aptitude for playing, parents were then encouraged to buy an instrument for their child so that the school instrument was then available for a new entrant. But a lack of money was never ever a barrier to opportunity.

It both saddens and angers me that in the 21st century a great many British children are never afforded the opportunity to get anywhere near a musical instrument, or even to sing. There must be thousands of people who are innately good musicians but are not aware of it, since they escaped what has become a very small net. I sometimes record in Helsinki with Finnish singers, and the educational structure there is beyond compare. All children learn to read music, sing and play; many have very little talent but at least they are given the chance to find out whether they do or not. This approach, more importantly, can foster a love of music. I realise that Finland is a small country with a population of 5 million but we shouldn’t be in the state that we are.

It was not just the grammar schools in Wales that offered free instrumental tuition: this was true of secondary modern schools as well, such as Penclawdd, where my father was deputy head. Coincidentally, my wife had similar opportunities in Leicestershire where there was also a vibrant music education policy. In 2013 I was involved in a radio debate about cuts in Wales when it was decided to end peripatetic instrumental teaching in Gwent schools. A question was raised in respect of Germany, where they were increasing such funding in difficult economic times. Germany saw it as ‘investing in the cultural future of the country’; if only we did the same in the UK. But I understand, at the time of writing, that cuts are now being introduced there as well. It is also a well-established fact that the learning of music helps skills in other areas. In addition, playing with others, as in a group or an orchestra, instils ‘old-fashioned’ virtues: loyalty, team spirit, discipline. This is why I would always recommend, if a child shows an aptitude for the piano, that he or she learns another instrument as well so that they can share the experience of music making with others, in an ensemble or an orchestra. Piano playing can be a lonely business but it is a great springboard for all music skills.

The peripatetic teachers my contemporaries and I encountered had ample credibility as instrumentalists in their own right. The cello, for example, was taught by Antonio Duvall, who had played in the orchestra of La Scala, Milan. I was somewhat ambivalent about what instrument I should try but my father, mindful of my growing ability on the recorder, suggested the oboe, the instrument he loved above all others. I had already started to play the recorder to a decent standard while at junior school, and the fingering, as with all woodwind instruments, is similar, so once I managed to make a sound, I could actually play some music.

My oboe teacher was Vincent Hanny, who, at that time, was playing in theatres in the area. We had one-to-one instrumental lessons once a week but they were rotated through the timetable so that we didn’t always miss the same academic lesson. Even so, in a school that prided itself on its musical prowess, some teachers were very condescending when one had to go and ask permission for leave of absence for a music lesson – a battle that one could have done without. However, some of the teachers actually played in the school orchestra. Glyn Samuel, a physics teacher, was a flautist, and George Bowler, the Latin master, played double-bass. Bowler’s lessons were a toss-up between learning some Latin or him regaling his captive audience with his war exploits with Field Marshal Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, KG, GCB, DSO, PC (he never failed to reel those letters off ). Every morning, the school orchestra would play for assembly – and once I was a half-decent oboist, a favourite piece of mine was Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony, since it has a fine oboe solo in the opening movement. For tuning up, C.K.Watkins had composed a clever little ditty called The Enemy, subtitled ‘Give us an A’, played on the piano, with a repeated A and changing harmonies underneath.

Come Christmas time, there were concerts involving the orchestra and choir and, as a woodwind group, we sometimes played for school productions of Shakespeare plays. We also (as English literature students) undertook school trips to the Royal Shakespeare Company at Stratford upon Avon. I saw Paul Scofield’s King Lear there. Many years later, I discovered that my future wife, who went to school in Leicestershire, had been on a school trip that season to the same play.

Five years behind me, playing the cello, was Dennis O’Neill, who was later to become one of the world’s leading tenors. We sometimes had guest musicians give recitals to the school: one was David Mason, a trumpeter who, in 1967, gained some fame by playing the piccolo trumpet solo on the Beatles’ ‘Penny Lane’.

As one became gradually more proficient, there was an established route to be negotiated to the National Youth Orchestra of Wales (NYOW), or the ‘Nash’ as it was called. The Welsh really do like abbreviations. The progression was the West Glamorgan Youth Orchestra (the ‘West Glam’), the Glamorgan Youth Orchestra (the ‘Glam’) and then the ‘Nash’. Attending the West Glamorgan Youth Orchestra was a logistical nightmare for me: it was held on Friday evenings in Neath and it involved two bus journeys. Getting there was possible but the return, via Swansea, meant I couldn’t get home, since the second bus service on the return leg had stopped running by then. We didn’t own a car; I went a couple of times but it proved too much of a trek.

My first rehearsal was scary. The first oboe player hadn’t turned up that evening so I had to sight read a piece that I hadn’t heard and which began with a fearsome oboe solo: the Overture to The Italian Girl in Algiers by Rossini. It was a shock but I think I got away with it. Just.

The Glamorgan Youth Orchestra was residential and met three times a year. These courses were held at Ogmore, South Glamorgan, on the coast. The place was a county educational establishment that had been some kind of military barracks in the past. We slept in long dormitories, two for boys, one for girls, and we had sectional rehearsals by day with full orchestral rehearsals in the evening.

I vividly recall the sheer weight of sound around me in the very first rehearsal when we struck up with the opening bars of Handel’s Water Music. It was incredibly exciting, suddenly feeling part of something on a grand scale, with dozens of other like-minded young people who were also eagerly exploring this music for the very first time. There would always be a concert at the end of the course in one of the towns of Glamorgan – never in Swansea or Cardiff, though, since they each had their own youth orchestra. Russell Shepherd, the County Music Organiser, was our conductor; he was an excellent musician but he could be a bit of a fusser. My favourite memory of ‘Shep’ was when, during a power cut in the middle of a full rehearsal, our principal cellist Wayne Warlow lit a match. ‘Get out, you madman!’ Shep screamed at him. ‘You’ll burn us in our beds!’

By this stage of my childhood, school was progressing well and I was usually in the top three or four come the end of the year. In the third year, we had to make choices regarding our O levels and take the arts or science route. I took arts but there was one anomaly even so. I had to make a choice between art (as in painting) or music. This seemed most odd to me. As well as music, I also loved sport, particularly athletics, at which I represented the school at county level. The long jump and the triple jump were my events. My enthusiasm for sport manifested itself in regular trips to Swansea with my father to watch the rugby.

When I was about sixteen, two important things happened. Firstly, my grandmother (Mam) died. She was a fine woman, the head of the family as I was growing up. She could look quite severe with her hair drawn back in a bun but she had a great sense of humour, was an excellent cook and had raised me with Aunty Ev and my father. Mam was the first deceased person I had ever seen. She had passed away in her sleep; I kissed her, said goodbye, and reflected on what a special part she had played in my life. The second moment of significance – and, thankfully, it was a far happier one – was that I then had an epiphanic moment at school when I heard jazz for the first time. Some of the more senior boys I knew from the orchestra were playing this strange and wonderful music on a record-player in the music room during a lunch break. The actual artist was the black Canadian pianist Oscar Peterson, and I was mesmerised. From that point onwards, I would be hooked on jazz, becoming avid in my reading about this music. I slowly built up a record collection to complement the classical one my father was building at home, and I also bought a tenor saxophone. This instrument, again, has similar fingering to the oboe and recorder, so I was soon up and running, trying to play along with some of the jazz LPs I’d bought.

As an art teacher, my father had graduates with him from time to time for teacher training. One such was David Randall Davies – also from Penclawdd – a very fine artist, who, although not a musician himself, had a passion for music. Together he and my father built a hi-fi system that sounded fabulous. They bought the mechanical units such as the actual speakers and amps but then housed them in acoustically designed but home-built cabinets. This was the time when stereo was first becoming available to the public. We had a stereo demonstration LP that included the sound of a train ‘going through the front room’. This seemed to impress visitors more than any music that was played.

As I moved into the heart of my teenage years, I soon found out about girls – or, more accurately, one particular girl by the name of Janet Williams. Janet was also from Penclawdd and went to Gowerton Girls’ Grammar School, which was about three hundred yards from the boys’ school. Many lads had girlfriends there and we used to squeeze through a gap in the fence and wander over in the lunch break, to chat through the railings. It always seemed to me to be akin to visiting jail. I was with Janet for quite a while, until my early twenties. However, that relationship was doomed from the day her mother said, ‘If you want to marry my daughter, you’ll have to give up the music!’

I was still sitting next to John Ratti, since we broadly took the same subjects for O level, one of which was Geography. He was still a joker. It was a particularly humid day and the lesson happened to be about humidity. The teacher (a not particularly pleasant man called Gilbert Davies) asked the class why the day was so oppressive and unbearable. John Ratti nudged me saying, ‘Tell him it’s because we have a geography lesson today.’ So, foolishly eager to oblige, my hand shot up and I answered accordingly. I was dismissed and banned from geography lessons for two weeks.

In 1962 I entered the sixth form, taking A levels in Music, English Literature and History. Initially there were three music students alongside me: John Weeks (flute), Wynne Edwards (trombone) and Derrick Cousins (horn). Like me, they were all were in the Glamorgan Youth Orchestra. Then Derrick decided to run away from home; I’ve no idea why. His family was Salvationist and he played tenor horn in the local Salvation Army band. I heard nothing about him for years and then learned that he had turned up in Canada.

Wynne Edwards had a terrible problem in that he used to have blackouts that lasted a few minutes. He would go ashen white and his body would freeze and become statue-like, even when he was standing up. There was no intimation as to when this would happen and he didn’t know himself. If it happened during a music lesson ‘Watty’ (C.K.Watkins) would whisper and tell us to pretend nothing was happening. I don’t know why, since poor Wynne was oblivious to it himself. It was darkly comedic, if rather cruel, that if it happened as we were leaving school and he was standing, boys would hang their satchels or coats on him. Wynne is no longer with us. He died young, no doubt because of his illness. No one ever explained what the problem was but it must have been a neurological disease of some kind. He wanted to be a teacher but was denied a place at teacher training college because of this medical problem.