Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'It is Williams's Welshness that makes the examination of her mixed-race identity distinctive, but it is the humour, candour and facility of her style that make it exceptional . . . an engaging and perceptive voice describing an engrossing and particular personal story.' – Gary Younge 'In its exploration of geographical, racial and cultural dislocation, Sugar and Slate is in the finest tradition of work to have emerged from the black diaspora in recent times.' – The Guardian 'Within this review, I can only scrape the surface of the many dimensions of Williams' memoir, so I strongly encourage you to read this precious book for yourself, and find those parts of it which speak most to you.' – Sarah Tanburn, Nation.Cymru 'Warmly recommended to any curious minds, at 20 years old Sugar And Slate still speaks to us in these modern times, helping to ensure marginal voices remain heard.' – Buzz A mixed-race young woman, the daughter of a white Welsh-speaking mother and black father from Guyana, grows up in a small town on the coast of north Wales. From there she travels to Africa, the Caribbean and finally back to Wales. Sugar and Slate is a story of movement and dislocation in which there is a constant pull of to-ing and fro-ing, going away and coming back with always a sense of being 'half home'. This is both a personal memoir and a story that speaks to the wider experience of mixed-race Britons. It is a story of Welshness and a story of Wales and above all a story for those of us who look over our shoulder across the sea to some other place. It would have been so much easier if I had been able to say, 'I come from Africa,' then maybe added under my breath, 'the long way round.' Instead, the Africa thing hung about me like a Welsh Not, a heavy encumbrance on my soul; a Not-identity; an awkward reminder of what I was or what I wasn't. Once at a seminar, one of those occasions when the word Diaspora crops up too many times and where there aren't too many of us present, the only other Diaspora-person sought me out. His eyes caught mine in recognition of something I can't say I could name, yet I must have responded because later as we chatted over fizzy water and conference packs, he offered quite uninvited and with all the authority of an African: 'People like you? You gotta get digging and if you dig deep enough you're gonna find Africa.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

About Charlotte Williams OBE

About Denis Williams

Title Page

Foreword

Epigraph

Preface

Africa

Small Cargo

Afternoon Dreaming

Africa to Wales

Alice and Denis

Beit-eel

Weddings, mixed blessings

Chalky White

Purple Haze

Icon and Image

Guyana

I goin’ away

Neva see com fo’ see

Expat Life

Parallel Lives

Tekkin’ a walk

Goin’ for X amount

The Jumbie parade

Wales

Sugar and Slate

Bacra-johnny

I goin’ home

Acknowledgements

Library of Wales

Planet advert

Funded by

Library of Wales list

Copyright

Charlotte Williams OBE is a Welsh-Guyanese award-winning author, academic and cultural critic. Her writings span academic publications, memoir, short fiction, reviews, essays and commentaries. She has written over fourteen academic books, notably the edited collection ‘A Tolerant Nation? Ethnic Diversity in a devolved Wales (2003 & 2015) and including an edited text in the Rodopi postcolonial series on her father’s work ‘Denis Williams: A Life in Works’ (2010), She is a Professor Emeritus at Bangor University and holds Honorary fellowships at Wrexham Glyndŵr University, University of South Wales and Cardiff Metropolitan University. She is a member of the Learned Society of Wales. Her writings have taken her on travels worldwide but her heart and her home are always in Wales.

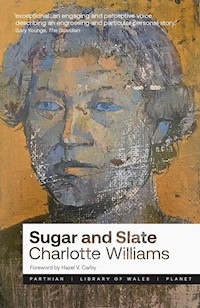

The cover portrait is of Katie Alice (1954) by Denis Williams

Denis William (1923-1998), artist, novelist, lecturer, archaeologist and anthropologist, was born in British Guiana. Williams was awarded a British Council art scholarship in 1946 to study at the Camberwell School of Arts and developed as a painter in London for almost a decade. He was the first Black artist to win critical acclaim in Britain and the first Black teacher at both the Central School of Arts and Crafts and the Slade School of Fine Art in London. In the early 50s he shared studio space with Francis Bacon, was celebrated by Wyndham Lewis and praised by Salvador Dali for his ‘Painting in Six Related Rhythms’ which is now in the Tate Britain collection. Williams was one of the few Black artists in post-war Britain to contribute to the British modernism of the 1950s. His painting ‘Human World’ (1950) would ultimately form the basis of Guyana’s National Collection. In 1957 he left London for Africa, bemoaning the influence of Europe on his thinking and artistic practice. He would write two novels whilst in Africa, Other Leopards (1963) and The Third Temptation (1968) and a pioneering treatise on African art, Icon and Image (1974) before returning to post independence Guyana in the late 60s, where he established the Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology.

Sugar and Slate

Charlotte Williams

LIBRARY OF WALES

Foreword

What does it mean for a book to be recognized as a “classic” and incorporated into the Library of Wales series of classics commissioned and funded by the Welsh Government? Why do I pose this question instead of taking for granted the common-sense definitions of “classic” such as: “of acknowledged excellence or importance;” “A work of literature, music, or art of …enduring significance;” “an outstanding example of its kind.” Sugar and Slate is a work of excellence but its enduring significance exceeds conventional judgments of worth in ways that make the work uniquely compelling, fascinating, and important. Classic is an evaluation and mark of recognition granted from the perspective of a status quo, in this case an institution representing the national values and interests of Wales; works endorsed as outstanding are regarded as exceptional in their power to epitomise, sustain and perpetuate the values of this status quo. Sugar and Slate, however, is an insurgent text, it does not seek to embody or affirm common sense or convention but passionately, powerfully and profoundly reveals and transcends the limitations of our measures of Wales and Welshness. Charlotte Williams expands the imaginative possibilities of what it means to be a Welsh “classic”.

The first edition of Sugar and Slate was published in the UK in 2002 and reprinted five times in the next four years. I live and work in the USA and was not immediately aware of the book. There is no North American publication but many university libraries own either the British or Jamaican edition. Alas, my own institution, Yale, is an exception so the first copy of Sugar and Slate I read came into my hands via interlibrary loan. It pierced my heart in the opening paragraphs. Both Charlotte Williams and I are the offspring of white Welsh mothers and black fathers from the Caribbean: Guyana in Williams’s case, Jamaica in mine. As a child I too had to carry the burdens Williams so vividly and poignantly describes: having to constantly explain where she was from; dreading the constant, awkward reminders “of what I was or what I wasn’t.” The young Charlotte and I were both defined as insubstantial beings, “mixed” or “half-caste,” forms of non-belonging. We were consigned to what Williams beautifully conjures as “a realm of some kind of half people, doomed to roam the endless road to elsewhere looking for somewhere called roots.” By the second page I knew I needed my own copy of Sugar and Slate, one that I could annotate. Through scribbles in the margins, I wished to stage an imaginary conversation with a writer I had never met and didn’t know if I would ever meet but with whom I felt an affinity. I was able to purchase a British edition from a black bookstore in Decatur, Georgia, evidence of who were the earliest readers of Sugar and Slate in the US.

Despite the existence of shared aspects of our racialized and racist experiences of what I felt was a stubborn Welsh parochialism, two distinct cultural and historical geographies of Wales shaped and influenced us. Charlotte’s mother spoke fluent Welsh. In London my mother constantly declared her deep allegiance to Wales but, having spent much of her own childhood in Somerset, she was unable to communicate with her relatives or think in its mother tongue when she stayed with them. The Wales of the long summers of my childhood was in the south, a rural village on edge of the Rhondda Valley where my mother was born. It was small and dominated by the history of coal and a family tied to the Great Western Railway until the arrival of the Royal Mint in 1969 rapidly expanded its population. Charlotte grew up in the coastal resort town of Llandudno, in North Wales on the Creuddyn peninsula that protrudes out toward the Irish sea although no one she knew from within their small community had travelled further than Pwllheli and Prestatyn: “We lived our lives bounded by the sea”, she says, “but very few had crossed it”.

Throughout Sugar and Slate, Charlotte Williams situates Wales historically and geographically within circuits of the Atlantic world which flow around the story of her emerging sense of self. In contrast to the stasis of Llandudno’s Victorian architecture and residents and the heavy weight of racialization bearing down on her soul “like a Welsh Not”, Williams as a writer creates a subject in motion. The restless currents of the book reproduce the triangle of the Atlantic trade in its three sections, “Africa”, “Guyana” and “Wales”. In its opening pages we meet an emergent subject who, when she thinks about Africa, thinks “about the beginning of my self”. At six years old Williams embarks on her first voyage with her mother and sisters to visit her father in the Sudan, a journey which is followed by years of “to-ing and fro-ing” to West Africa. As an adult, authorial moments of reflection “back into memory”, are generated “in transit” as she waits “at Piarco Airport in Trinidad, caught “in moments between somewhere and elsewhere.” Stilled, waiting, in the Caribbean, this figure is a fulcrum for cultural, collective memories which reveal the historical and geographical reach and connective tissue of colonization, empire and imperialism.

Many stories in Sugar and Slate reveal the complex entanglements of Wales with Africa and the Caribbean. Hundreds of Welsh missionaries were dispersed to various regions of the continent and brought home to their parishes stories of Africa which became embedded in the cultural memory of generations. In the other direction the Elder Dempster Shipping Line carried “a hundred and fifty boys and one young girl from African villages in the Congo, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, Liberia, South Africa and more” to Liverpool and the North Wales Steamship Company bore them to Llandudno and then on by pony and trap to Colywn Bay where, in the late nineteenth century, the Reverend William Hughes established an institute to train African missionaries. Williams also reveals the entanglement of Wales with the trade in enslaved human beings through the iron industry, how “iron masters grew wealthier and wealthier ploughing back the profits of spices and sugar and slaves to make more and more iron bars and then manacles, fetters, neck collars, chains, branding irons, thumb screws…. copper and brass from Parys Mountain and the Mona mines in Anglesey that sheathed the slave ships and supplied them with plates and pots and drinking vessels”.

The excavation of these cultural histories is enriched by personal histories, stories of Williams’ immediate and ancestral family, and anchored throughout Sugar and Slate by Charlotte Williams’ own life history and pursuit of the security found through sense of belonging. She reveals the intimate afterlives of imperialism and empire showing how legacies of colonization, race and racialization are lived by individuals and enacted in and shaping everyday relationships. These entanglements are gently unravelled in her account of the stages of her father’s lifelong struggles to throw off the mantle of being a colonial subject in diaspora: they begin with Denis Williams coming to know himself as West Indian during his first journey into exile in the mother country; continue as he fails to reconcile his colonial inheritance of a European mind with his desire to fully embrace the spirit of his African descent; and appear to resolve, or at least to reach an apparent settlement with his return to live in Georgetown. Charlotte Williams sojourn in Guyana hoping to find a place to settle does not offer closure to her own long journey to resolve the conflicts of displacement. As she concludes: “the Caribbean was created and is recreated as a huge mix of races and cultures, a congregation of the dislocated and the dispossessed. The heritage is so Creolised that it’s easy to be fooled into thinking you can just blend in.” The problem was that Williams was so busy moving that she didn’t stop to think that she “was looking in all the wrong places.” The place she needs to return to and confront is Wales.

Williams traces her maternal ancestors who lived and died in Bethesda in the shadow of a “great slateocracy” run from Penrhyn Castle by Richard Pennant. In this account Charlotte Williams weaves the inextricable relations between family, communal and national history. Pennant was one of the wealthiest men in Britain who built an industrial empire from the brutal exploitation of the Welsh workers who quarried the slate in his two quarries. The quarries were purchased with a fortune produced by enslaved labour on his West Indian plantations. “It was the cruelly driven slaves; men, women and children who toiled and sweated for the huge sugar profits that built the industries in Wales. Out of the profits of slave labour in one Empire, he built another on near-slave labour. The plantocracy sponsored the slateocracy in an intimate web of relationships where sugar and slate were the commodities and brute force and exploited labour were the building blocks of the Welsh Empire.” This is the historical legacy that Sugar and Slate forces us to confront and is its enduring significance. If we do not act to repair historical injustice, we cannot build an equitable future.

Hazel V. Carby is the author of Imperial Intimacies, A Tale of Two Islands (Verso, 2019) which was awarded the Nayef Al-Rodham Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. She grew up in south London, the daughter of a white working-class mother from Wales and a father who was recruited from Jamaica to serve in the RAF during the Second World War. She has written widely on Black British and American culture including Race Men (1998), Cultures in Babylon: Black Britain and African America (1999) and Reconstructing Womanhood: The Emergence of the Afro-American Woman Novelist (1987). She is the co-author of The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain (1982).

She is the Charles C. and Dorothea S. Dilley Professor Emeritus of African American Studies and Professor Emeritus of American Studies Yale University, a Fellow of the Royal Society for the Arts and Honorary Fellow of the Learned Society of Wales.

Will you fly or will you vanish?

Caption from Asafo! African flags of the Fante.

Preface

I grew up in a small Welsh town amongst people with pale faces, feeling that somehow to be half Welsh and half Afro-Caribbean was always to be half of something but never quite anything whole at all. I grew up in a world of mixed messages about belonging, about home and about identity.

It’s a truism that those who go searching for their roots often learn more about the heritage they set aside than the one that they seek. In the 1980s, serendipity took me to the Caribbean, to the country of my estranged father and I began a journey I had not anticipated. It was a journey that took me across a physical terrain spanning three continents and across a complex internal landscape. If I set out with the idea to document something of my searching as a second generation black Briton, what began as an account of a journey became an account of a confrontation with myself and with the idea of Wales and Welshness.

This is a story of childhood and youth, of Welshness and otherness, of roots and rootlessness, of marriage, connection and disconnection, of going away and of going home.

Africa

Small Cargo

It would have been so much easier if I had been able to say, “I come from Africa,” then maybe added under my breath, “the long way round.” Instead, the Africa thing hung about me like a Welsh Not, a heavy encumbrance on my soul; a Not-identity; an awkward reminder of what I was or what I wasn’t.

Once at a seminar, one of those occasions when the word Diaspora crops up too many times and where there aren’t too many of us present, the only other diaspora-person sought me out. His eyes caught mine in recognition of something I can’t say I could name, yet I must have responded because later as we chatted over fizzy water and conference packs, he offered quite uninvited and with all the authority of an African: “People like you? You gotta get digging and if you dig deep enough you’re gonna find Africa.”

I wondered if my name badge carried some information lost to me or whether it was just the way I looked. I felt as if I had entered the realm of some kind of half people, doomed to roam the endless road to elsewhere looking for somewhere called Roots. I was annoyed. Maybe Alex Hayley had committed us all to the pilgrimage. I found myself thinking about all those African-Americans straight off the Pan-Am in their shades and khaki shorts treading the trail to the slave forts on the beaches of Ghana. And then I thought about all those who couldn’t afford the trip.

I thought about Suzanne. We were sitting drinking tea by the coal fire at home. “I has this friend see,” she was saying in her strong south Walian accent, “with red hair and eyes as green as anything. She passes herself as white but Mam told her straight — you’re black you is, BLACK! I know your mam and she’s black as well so don’t go putting on any airs and graces round ’ere.” She had a way of talking over her shoulder in conversation with her imaginary Mam. She paused a little and then turned to Mam and said in a lowered voice, “Well I’m not wearing African robes for nobody, Uh-uh, not me.” Mam didn’t respond and we fell silent. That’s the Africa thing. It just pops up again and again like a shadow.

When I think about Africa, I think about the beginning of my self. I open my memory eye and there is only one long journey in which I am various ages between three and twelve years old. One composite to-ing and fro-ing. Dad wrote,

Kate sweetheart,

I take over the house on Saturday; that is, by the time you get this. I applied at once for permission to bring my family and for the necessary arrangements to be made. I suppose they’ll now write to the Sudan Embassy, and then things would begin to move. Tell everyone you like now about the house. I didn’t want them to laugh at you if it didn’t come off, and of course, I didn’t want the children to be disappointed. I feel absolutely magnificent — physically, mentally and about everything in general. I’m afraid my last letter to you was a bit nervous (about publishing etc) and I never ought to have sent it. I feel much more confident now in my own power. I do not need acquired skills to face the future with. I feel now I’m worth much more to myself and to everyone as what I am — an artist, and must try to work right up to the brim of my own possibilities. Five years is not a long time for work or for love but we’ll use every moment of the time doing both. Then we’ll see. I know this will make more sense to you. I love you. D

I am six years old. “We’re going on a boat to Africa,” Ma has announced. I tell Ann Morgans and Diane and Mrs Jones fach1 who lives on the corner and they nod like when I said, “I’m going to Auntie Maggie’s on Saturday.” That’s the way it was. Nobody we knew from within our small community had travelled. Well, only to Pwllheli and Prestatyn and the like. We lived out our lives bounded by the sea but very few had crossed it.

We sailed there by cargo ship the first time. A paint-peeled ocean-goer called the Prome; soft white letters printed on a charcoal background. It must have been to-ing and fro-ing this ancient marine route for years by the time it carried us outwards from Liverpool dock. Ma glanced over her shoulder but kept going. Wales was behind her now and she could only move forward as she had done many times before. In the sweep of her skirts we were voyaging to a different world. Dad had already been in Africa for one lonely year when he sent for us. Just Ma and four small girls made our family then; teulu bach.2 Just a small cargo on a big ship.

There is a curious intimacy about these cargo passages that one doesn’t experience on passenger liners. A few cabins on loan to a handful of purposeful passengers for three weeks or so. Over hundreds of years small cabin-loads of explorers, missionaries, those in the service of the Colonial Office and their families have been transported in this way, their stories and their histories becoming intertwined by these sea crossings. They are the people who opened up the connecting routes; the ones who crossed the maps drawn out by Church and Empire. From 1868 Elder Dempster had a fleet of steamers following the infamous route to and from the Dark Continent. In later years we would travel to and from the coast of West Africa aboard luxurious dazzling white passenger liners; the Apapa, the Accra, the Aureoll. But at first we went cargo to the Sudan.

It is surprising how you first notice difference as a child. A missionary family travelled with us on the passage I am remembering now. They were heading out to work in old Omdurman. They were noisy, and unlike us they spoke proper English. The mother had a loud challenging voice like a teacher, her mouth opening long and wide with every word. The father wore long socks with sandals, the type worn by older men today. He had too many words in his mouth as I remember and overly explained everything to their three children who all looked and dressed exactly the same, in the way English children did. Then there were some very pale nuns, white as their starched collars and some stiff foreign office people with world-service accents going to Aden. One of their group was a younger man, a fresher on his first tour to what must by then have been the vestiges of the colonial administration; part of the mopping up job I suspect as Nkrumah brushed out the pink paint on the map of Africa. “Creative abdication” the British called it. Only pieces of these memories come to me now, pieces that shaped me. The memories don’t fall out in nice neat lines as they seemed to do when there weren’t so many of them.

We move out across the Bay of Biscay where the storms lash the sides of the ship and pitch and turn us till we all lie down seasick for three days. Then into warmer waters and warmer days when schools of dolphins appear and swim alongside the ship, a happy squeaking escort that brings our entire passenger group out onto the deck. The crew put up a makeshift canvas swimming pool on the rear deck. I can smell the wet tarpaulin now, filled daily with salty sea water which moves in rhythm with the waves in the huge wide sea, so that we are tossed and showered and bobbed and ducked until we will never again misjudge the power and the perils of the ocean. The missionary children are not allowed to participate in the fun but content themselves instead with standing nearby and staring. I can smell the ship’s ropes and the bleached wooden decks. We find some hessian quoits that we wear as heavy armlets or anklets in our small-girl play, and we sing a Welsh song about a saucepan and a cat that scratches Johnny bach.3 The wooden rails of the ship’s sides taste of the sea. Everything tastes of the sea. “Why do you have to put everything to your mouth Cha?” Ma is saying. “Ych a fi.”4 I’m not listening, only tasting and feeling.

There are areas of the boat barred to us. Over the rope boundary we can see oily black pulleys, coils of rope, rusting pieces of machinery and the sailors — rough sailors, the engine wallahs, the deck hands and the cooks and cleaners taking a cigarette or just emerging from the underworld to squint a few minutes daylight. They are on the other side of things from us. They are very different from the smartly dressed officers who change from their blues to tropical whites and from whites-long to whites-short as the voyage takes us towards the Mediterranean. We spend whole days out on the decks, hair fuzzy and free, skin colour changing from pale to mellow browns. And by night we sleep in the belly of the ship lulled to sleep by the hum of the engines and the creaking of the old boat’s aching structure as she rolls with the waves. We are suspended, with the echoes of our forefathers rumbling below.

Ma is happy on the sea. She prefers to travel this way. She likes these voyages; both the drift and the drive of them are part of her make up, carried along with a helplessness she courted. “Why did you bring me here?” she would demand of Dad in the months to come. Yet this passage was part of her own inner drive to move out from under the claustrophobic pile of slate that was her birthplace. I would come to know her as sacrificer, sufferer, survivor. She had a steel will that had pushed her away from all the chapel goodness, the village small talk, from the purples and the slate greys that invaded her inner landscape. In its wake came a fatalism that she could not shake off. It haunted her. But she was suited to the slow acclimatisation in the space of the voyage. The place between somewhere and elsewhere was so right for her.

I think about Ma as I wait in transit at Piarco Airport in Trinidad, caught up in those same kind of moments between somewhere and elsewhere. Eight hours from Manchester and one hour from Georgetown. I’ve been delayed for four hours in this limbo, wondering and waiting for an explanation as the BWIA5 planes touch down and take off in a constant stream of traffic across the Caribbean. I once saw a programme on the telly about the man who has been trapped in the in-transit no-man’s land of Schiphol airport for years as no country will accept him. He lives his life out of the only small piece of hand luggage he pushes around on a baggage trolley and appears curiously content with his synthetic desert. He engages with a small cohort of familiar passengers who pass through regularly. “Who am I? I am that man at Schiphol Airport,” he says.

I have rehearsed his scenario several times already. I suppose there could be worse airport lounges than Piarco to be held up in. It’s got a friendly small-place feel to it and those coming in, those leaving and those just passing through, all muddle together like guests at a party. I’ve been here many times before and I’ve come to expect these delays as part and parcel of my journey. I’ve looked in my purse and worked out how many Eastern Caribbean dollars will keep me in Carib beers and sandwiches. Opposite me a Rasta guy is sleeping across four chairs. He is wearing an oversize woolly hat in “the colours” and his crumpled tee shirt has a map of Africa printed on the front. Somalia has become part of Mozambique, whilst Zanzibar has disappeared under his left arm. That’s the Africa I know — all merged into one big place. I am quite adept at sketching Africa. I remember at school how swiftly I could draw the Dark Continent freehand, like a body map with the great veins of the Congo and the Nile and the Niger and the vast open deserts like skin.

Ma was never good in small spaces. I imagine myself small again, flung back into those snatches of memory that make up my Africa. Just once we fly to Africa and there are goody bags with BOAC6 written on them for all of us. The insides of Ma’s hands are red and there are beads of sweat sitting quietly on her nose. We are boarding the plane which has a cold grey outside that looks like it will taste of pencil lead. There are lots of waiting people and bags ahead of us and it seems as if there may not be room for us. A woman with a loud English voice says “Excuse me,” and pushes past Ma to the front of the boarding queue. Ma just ups and grabs her by the neck of her blouse and starts to shake her like a piece of washing. “Blydi Sais,”7 Ma says. “Just who do you think you are, Queen of the Cannibals? How dare you. How bloody dare you.” Thumb in mouth, I try to shrink myself into the folds of her skirts. Ma is in a complete rage, shouting and flapping her arms. Beads of sweat have broken out on her top lip too by now. Eventually the Captain comes to see what the problem is. “See that one,” she says to him, “She thinks she can treat me like a dog, putting on airs like she’s somebody.” Lots more “How bloody dare you’s” and “Who do you think you are’s” follow before she can be pacified. The Captain calls Ma “Ma’am” very slowly. He tells her that they are first timers to the colonies and they don’t know anything about Africa or about coloured people and so she lets it go, for now at least.

This battle would be part of what we were and what we would be, although I can’t say I knew at that stage of my life what the battle was about. I guessed, like Dad said, it was because Ma was Welsh and she wasn’t taking orders from anybody. But she was beautiful at sea. The cool openness on the decks, her wild beauty matching the elements; the blue of the waves and the blue of her eyes. Africa had called for Dad and now he was calling for her; Kate sweetheart, his love and his mentor. He loved the rhythms and poetry of her thoughts. Her ideas fell together like jazz, the blue notes resonating across the staves with their own logic, defying the predictable sequences and the rudimentary facts. He would not be without the magic that was her. She was shaping him; her mind was his umbrella and beyond this umbrella he dared not step. “Paid a phoeni Denis bach8… Everything will be fine,” she would say. She provided such spiritual security for him. She was our backbone.

Behind them they left London. The London of John Nash, Wyndham Lewis and Elgar that very gently nudged them away with all its imperialist assumptions and its contradictions. That London would never be the same after the Picasso exhibition in the V&A took the country by storm, the influences of Africa cutting through the canvases like a knife. A London of immigrants. Sam Selvon’s London; a cold, grey and miserable motherland.

There had been much pillow talk about the move out to Africa. They had discussed it over and over again, trying to anticipate the future. It could have been different. They could have stayed on in London; things were going well. Dad had a teaching job at the Central School of Art and several major exhibitions behind him with excellent reviews. I have a scrapbook from this time that Ma must have put together. Wyndham Lewis wrote in The Listener about a “brilliant newcomer” — his huge canvases hanging on the walls of the Gimpel Fils gallery bursting with colour and symbolism. Dad had painted Human World. It was magnificent, painted in equatorial reds, yellows, ochres and greens with tree-like people standing and glaring with large threatening eyes as if the Empire might stand up and strike back. It was pure savagery confronting civilisation. When I read the old fragment of The Listener, I saw all those assumptions that pushed them away; all those assumptions that lay deep in the lines.

In spite of the fact that Denis Williams speaks with an unmistakable Welsh accent, he is a Negro. But because of the Empire-building propensities of the Briton of yesterday he is British for he comes from British Guiana. Georgetown, the capital city, is where he lives. It is anything but the jungle: there are splendid boulevards lined with blood-red trees, a fine hotel (for Sahibs only), a busy port. The Negroes are tennis and cricket playing Negroes; Milton and the other national poet Shakespeare, is what they are brought up on, but especially Milton.

How could this country have held him with all its double speak? Wyndham Lewis was a Welshman, Ma told us later. “He was the one who said that the coloured men of London were all boxers and sailors and that we should move on,” she said.

But Ma and Dad rubbed along the edges of a very glamorous London, moving in circles that included Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud and other equally well known artists. Dad was artist-in-residence at the Slade for a while. He became the interesting chap to have at parties; a curiosity, a poodle, the comfortable stranger. Ma was not so easy. She was Welsh and uncomfortably different. “You’re the English one,” she used to say to Dad, knowing in her heart that she was the real dark stranger.

Their real life was a small cramped flat in Oxford Road, where Dad hung up his smarty-boy suit on the back of the door at night and set to work painting whilst Ma’s wages from a job in a book warehouse kept them going. At night the West Indian chaps dropped by; Michael Manley, Jan Carew, Wilson Harris, Forbes Burnham, were all regular visitors. Gathered in that small space they talked about imperialism, about colonialism and independence. They were the Caribbean writers and artists and future leaders with visions and big thoughts, not boxers and sailors. They were planning a different world. And the stuff of their talk was the destiny of their own countries and news of Africa and Nkrumah in his fight for independence. That was their struggle; they were not concerned with their position in the motherland. For them the motherland was only ever to be a temporary host, so although they knew the colour bar, they didn’t need to take it on. They knew it was difficult to get lodgings and in many a bar they would be told, “Sorry but we don’t serve you chaps in here.” But it was all very polite; so very polite and so accepted.

When Welsh and Irish girls came to London looking for work they found the same lodging houses willing to let them in as the coloured chaps. It was Mrs Dovaston who took in Katie Alice and found Denis on Kilburn High Street and invited him back for tea. Ma said Mrs Dovaston’s own granddaughter Josephine was a black girl and that her father had played the piano for Paul Robeson in America. I suppose she liked having coloured people round the house for Josephine’s sake.

So Ma and Dad became lovers, eventually married and moved on. That’s how we began to learn about movement. It was movement that was home. Home was not a particular place for us in the very early years. Home was Ma. We arrived into an exile; into a state of relocation that was both hers and his. And the journeys were more than physical journeys. They were travels across worlds of thinking, across generations of movements. These boat stories and seascapes, I now know, are part of a collective memory lying buried below the immediate moment.

Slowly the boat days grew longer and the small passenger group became politely accustomed to each other and shared table and time. The colonial boy with the books found his own space, aloof and largely indifferent to the rest of us. Just occasionally he had a way of announcing things authoritatively that spoke reams about his mission. “Khartoum,” he says and pauses for the audience to attend. “Lord Kitchener laid down that it should be built on a grid in the form of a Union Jack.” And so he went on like he alone owned the knowledge. The cackle of the group heading towards Aden mingled with that of the missionary family in a noisy chorus. We were apart from all this. Ma was not one for mixing. Perhaps she was mistrustful of them. She would sit on the deck in her sunglasses with her scarf tied Audrey Hepburn fashion and watch over us.

From time to time however, the group of passengers came together with some of the more senior members of the crew at the Captain’s table. I remember one particular occasion at the Captain’s table when the missionary group were brought to heel by Ma’s tongue and made to treat us with the respect she demanded. She had maintained a chapel silence for some five long days when their proselytising caught her attention. Clearly suspicious of her association with the Dark Continent they had made presumptions about her soul. “What right have you to assume that I’m not saved?” she suddenly levelled at them across the dinner table. The shot flew though the air bringing an embarrassed silence that is now so familiar to us. It quietened their talk and averted their eyes. She had mastery. Ma and her Bible talk; she wielded Bible metaphor like a weapon. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” she might sometimes ask. But more usually by careful inference she could confer the restraining power of scripture. She was not a preacher like her sister Maggie, but her speech was framed with spiritual reference. I never remember her having any small talk; it wasn’t her way. I think that is how we understood her as Welsh at first. Contrary, confrontational, biblical and a passionate stranger. Ma’s intuition was rarely wrong. She stood on guard against assumptions. I longed for her to be ordinary but she wore her difference like a banner. She was flamboyant. I see her in this wonderful rich patterned dress, a kind of Mexican dancer style with puffy, small, off-the-shoulder sleeves and a huge skirt. It was magical and it captured the wildness of her spirit; the rebel in her. The waves moved us towards the scorched country. Sand, scorch and semi-scrub; Sudanic mullatto Dad called it. Africa was pulling him in; it claimed him bit by bit and he was excited by all that it offered him. The country drew us to its desert plains, to the calls of the muezzins echoing across the city of Khartoum from the mosque towers that pierced the city skyline, towards the smell of neem, mimosa and camel dung. I can see those clear starry night skies from my seat at the back of Dad’s Landrover. I can taste the dust thrown up from the desert trails.

I am caught up in tiny moments, pictures of Africa flicker across my memory-eye in brilliant colour. As the ship nears ancient Port Said, tiny boats come alongside. At first just one or two, then there are many. Tall thin Africans with wild unkempt hair stand steady in the little boats as our ship comes to a slow halt. Matt black, midnight blue black, then indigo as their skins pick up the colours of the water. I have never seen anyone like them before. These are not Arabs; they are darkest Africa. I watch the dark strangers from the vantage point of the huge ship. I stand amongst the pale nuns and the Colonial Office people and the missionary family looking at the strange beings without recognition of what they are. “These are the Fuzzy-Wuzzies,” the colonial boy says as though he has just looked it up in one of his manuals. “The Baggaras. We call them the Fuzzy-Wuzzies. My father used to say, ‘Big Black Bounding Beggars that Broke a British Square’,” he tells us, mustering all his self-importance. The Fuzzy-Wuzzies watch us, steady-eyed. Deep behind my eyes is fear and curiosity that asks questions of the beings within those dark skins. Their half-naked bodies, their primitive wholeness leaves my mouth hanging open. I can’t taste their difference but I can see it. Their hair is dull and huge on their thin angular black faces and when they dive for the coins we throw overboard into the deep blue, the creatures emerge with their hair intact as though no water has penetrated the fuzzy mass. What devils of the sea they are to me. What a spectacle. The space between the Prome and the dock is filled with small boats and confusion. The entire crew is out flanking the side of the ship. We stand with our small brown faces, our own fuzzy wuzzy hair, our white Welsh mother and the officers of Her Majesty the Queen. There is Africa below and we are safe Britannia. That’s how I first saw Africa.

It said British in Dad’s passport and British in Ma’s and that meant all that was good and right and ordinary. Africa was the real stranger. The body map was not yet mine. It was all outside of me. I glimpsed it but I would not recognise my connection to it for years to come. And yet in those small moments an imprint was made; an unconscious but indelible imprint that means I stare at the Rasta man’s shirt now and know something very deep gives it meaning to him and to me.

1 Welsh: literally “Little Mrs Jones”, but used as a term of endearment.

2 Welsh: “small family”.

3 Welsh: “Little Johnny”.

4 Welsh: “Ugh!”

5 British West Indies Airways

6 British Oversea Airways Corporation

7 Welsh: “Bloody English!”

8 Welsh: “Don’t worry Denis dear”.

Afternoon Dreaming

Five-thirty in the afternoon and my Piarco anxieties are rising. I doubt that I’ll ever be able to shake off the sense that things aren’t going to go smoothly. Piarco might be the Crewe Junction of the Caribbean, but at one time it wasn’t unusual to arrive at the transfer desk after a gruelling flight from London to hear the desk officer say, “I’m sorry madam but the plane is full,” or “I’m afraid there has been a double booking.” I’ve even been offered the jump-seat before today and spent what was actually a very pleasant two-hour flight peering out of the cockpit from between the pilot and co-pilot. I wouldn’t say “no” to the jump-seat right now in exchange for the absolute assurance that I will be leaving here today. I turn up the volume on my Walkman, sit back and close my eyes. I dread that at any moment I could get caught up in yet another of those endless conversations with someone about who’s who and who’s related to who, in which we have to go all round the houses, or the islands, I should say. “Well yuh know Byron James… he brudder’s boss-man Henry, right? Well Henry’s wife is you fadder’s cousin, right? Well…” on and on and round and round until we get back to find that we are all bonded in some infinite familial web. It’s the same in Wales. As gateway to the Caribbean, Piarco has almost become the official national meeting point with all the connecting work to do like that of an eisteddfod. I met the Mighty Sparrow here once — all gold rings and silk shirt and a big booming voice. He wrote his sprawling signature on the back of my return ticket “Mighty Sparrow, King of Calypso”. When I got to Georgetown I went straight out and bought his tape; when I left I had to relinquish my ticket and proof of any association with him. Life can be so cruel.

It’s not too difficult to spot those who are going to Guyana. For some reason it’s almost impossible to pass through this airport without at least one piece of your luggage getting left behind, so travellers en route to Georgetown are trying to carry their immediate needs along with every anticipated shortage in the Guyanese economy in their oversized hand-luggage. And when the plane finally does begin to board, arguments will break out between passengers and cabin crew about which bags won’t be allowed in the cabin and there will be a delay of at least another hour while the Captain is called to sort it out. I find myself mentally weighing up people’s hand luggage as they begin to congregate around the departure gate; yes, they’ll let that one on, or no, that one’s got no chance. Then there are those travelling outwards from Georgetown. Like the wide-bottomed auntie who, despite the heat, is already dressed in her London coat, hand luggage straining at the seams to accommodate two dozen rock hard mangoes, a jar or two of achar and four bottles of XM rum — that little taste of Guyana for the relatives outside. I guess by now I am getting to be an accomplished observer.

Rasta-man’s hand luggage isn’t giving too much away but I try to read other messages about him. I watch as he turns over slowly and frees up the scene of Africa. I realise how easily he carries me back into Africa days — to some of my earliest memories of the Sudan and to my childhood memories of Nigeria. Two very different places have melded over time to become one Africa for me. I can’t help wondering about Rasta-man’s Africa; I’m curious about how he carries it with him. Is his Africa in the food he eats, in his music, his poetry? Does he talk it up in his everyday chat; is it in his dreams or is it simply printed on his tee shirt? Why do we carry Africa around with us like this? I doubt he’s ever been there, but what the heck; Africa is his spiritual home and he sleeps easy with it despite the hustle-bustle and noise all about him. He reminds me of a soldier, sleeping with part of himself on guard. I begin to relax with his sleepy pose and his sleeping Africa. There’s his history and there’s mine and I let them mingle together. As he sleeps with his picture of Africa, I pull out mine.

Colonizer’s Logic

These natives are unintelligent —

We can’t understand their language.

Chinweizu

Africa days punctuated by afternoon sleep. The heat demands “slow” or “sleep” and for the majority the choice is sleep. The women in the market pull their babies to their breast and lay down beneath makeshift stalls in a cool womb of shade. The window shutters close off the blast of the heat and the servants retreat to their quarters, first to eat and then to sleep. There’s a lull. It’s a time of quiet unaccompanied by the chorus of the night beetle or the rattle of the swamp toads that will come later. The forest is hushed too. Afternoon sleep is deep sleep. The driver sprawls across the front seat of the yellow municipal bus seemingly oblivious to the passengers who may soon join him in slumber. Stopped dead.

The afternoons are over when the six o’clock flower opens its evening face. Ma will make sweet tea with condensed milk served in glass cups and then teach us how to sew. Then the sounds of the night begin, the mosquito coils are lit and the fireflies sparkle in the dark spaces like the stars in the African sky. And in a brief twilight space Dad will type a few more lines of his book:

Siesta. The whole country flat on its back. The streets lay down like dead zebras: ochre striped with black, so secret and private you felt you had no right. Goats noiselessly reduced the careful hedges to skeletons; the hour your front gate is furtively opened and the animals let in to finish off the lawns; let in by the police, too, who show lethargic indignation in face of protest.

In the cool of the evening Ma will read over Dad’s manuscript and then they will argue while Joseph the servant boy makes peppehstew and hums a tune over his work.

But for now, along with most, they sleep and in those few hours long spaces open up to us like a reprieve. Time slows. The geckos and the wall lizards stand still in the intense light and baking heat. Only the children and the columns of ants move on. These are times of adventure and growth; times when all the rules are suspended as we little people are left on trust to shape our own worlds. In these free and open spaces we cross boundaries and discover our own Sudan and later our own Nigeria, our Africa.