9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Youcanprint

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Without any certainty about his birth, Sylvester grows up hidden from the community where the woman who took custody of him live, until, on one of the rare exits from the family home, he is noticed by a baseball coach. His talent is such that many are working to regularize his documents and allow him to attend schools that will increase his sporting abilities without, however, worrying about his education. Sylvester, who excels in basketball, is a potential economic asset for many and will be one of the pieces of a billion-dollar business that will lead him to be chosen early in the 1988 draft by the Miami Heat. Alienated from the protagonism of NBA players, he plays in different leagues and countries, until arriving in Italy, where he builds a successful career, but the years pass, his sporting parable becomes descendant and his family, which has always lived on his earnings, turns their back on him. Without family relationships, without a job, without a residence permit, but free from all constraints, Sylvester sets out in search of his primordial roots. Thus began for him a second life of study. Through the written word, experienced since childhood as a difficulty, Sylvester manages to place himself in a broader context, that of a people.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Index

Preface by Sylvester Gray

Prologue

The hidden child

Towards other worlds

The system

Blue Chips

A balcony overlooking the ocean

The dream catches fire

Beyond the border

The watch with a soul

I know my body

The land of Yam

The labyrinth

The return

The found child

Thanks

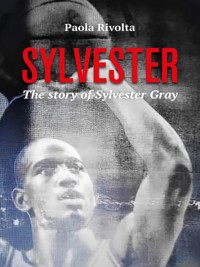

Title | Sylvester. The Story of Sylvester Gray

Author | Paola Rivolta

ISBN | 979-12-22737-78-2

© 2024 All rights reserved by the Author

No part of this book may be reproduced without the prior permission of the Author.

Youcanprint

Via Marco Biagi 6 - 73100 Lecce

www.youcanprint.it

By the same author:

Scarfiotti. Dalla Fiat a Rossfeld, Liberilibri 2018

femm., Liberilibri 2019

Paola Rivolta

SYLVESTER

The Story of Sylvester Gray

PREFACE

The origin of my athleticism

by Sylvester Gray

Many have wondered what the origins of my sporting skills were and how they developed.

Everything I know about sports began in the Harrold Project, a neighborhood in a small town called Millington, located in Shelby County, Tennessee.

Baseball, football, soccer, tennis, volleyball, horseshoes, athletics... every sport was learned in that area of America because it was a melting pot of highly skilled athletes.

In the first years of my life, which I lived far from the ‘system’ and which I call the ‘ghost years’, I began to become a great athlete.

At that time, I was prohibited from participating in Little League basketball and football because I didn’t have a birth certificate, so I often played with adults and with them I tested my skills.

Basketball. There was a kid, younger than me, named Gregory Seals and he had a basketball hoop in the yard. It was the only place where he and I could play because we weren’t old enough to go to the park. At 8, 9 years old we fought our battles there. My passion for basketball began in that courtyard. Once we had the chance to go to the park, we had to practice shooting the ball between the bars of the monkey bars, because we weren’t allowed on the basketball court yet.

Football. As a child I remember one day I was watching an NFL football game and I saw this Pittsburgh Steelers’ player named Lynn Swann and in my head I said to myself that I wanted to be like him in running and catching the ball and I started to copy his style.

Track and field. It was my sister Dorothy Jean Gray who was my point of reference. She was very fast and I was never able to beat her. We have faced each other hundreds of times in life without me ever being able to win!

Baseball. It was my brother Robert David Gray who woke me up every morning to get me to throw the ball as hard as I could, until my arm hurt.

By the time I reached high school I was completely ready for all sports.

In total I played organized sports for only four years before becoming a professional basketball player.

I hope that this book helps many to understand the path that led me to get here and to understand the origin of my excellence. Credit goes to all the great athletes who set an example for me and were trapped in Millington, Tennessee.

I managed to free myself from that grip of hatred.

I have met many people on my journey, towards whom I feel grateful; first and foremost, my mother Sarah Beatrice Gray, a protective warrior.

And, in no particular order:

all my fans who supported me all these years and motivated me to improve myself.

Coach Branch, the man who fathered me and left me alone, too soon, in a world of vipers.

Bobby Watson, who collected the articles on my sporting exploits and gave them to me after thirty years.

Catherine Williams and family, who took me in and kept me safe when the town of Millington made sure my mother had to leave the Trailer Park. Catherine was my second mother.

Kathy Gray, who often, while braiding my hairs, mentioned that my mother founded me in a garbage can.

Craig Moore, one of the purest shooters I saw in high school besides Roderick Jones.

Sylvester Gray Jr., who showed me the list of my transfers from one team to another since I was in high school, a list that started a lot of reflection.

Simona Mancinelli, who gave birth to our wonderful little girl and nourished her, keeping her healthy.

Wendy McPherson, who accompanied me to the London Library of Black Authors and to the first museum I visited in my life: the British Museum.

Laura Salvucci, the first to show interest in my studies of Black History and to show me the first Egyptian artifact I saw in Italy.

Laura Antonelli, an extraordinary organizer who helped me start the basketball camps and accompanied me to discover some of the main libraries and museums that preserve Etruscan history and artifacts from Black History.

Patricia Malidor, who is the only person in the world who has seen my birthplace and who has collected testimonies about my life since its beginning.

Elvin Leroy Taylor Sr., who helped me find my first job when I was a boy and nurtured me with his affection, and his son Elvin Leroy Taylor Jr. who organized the welcome home dinner when I returned to the Americas after many years.

Michael Kimmons, one of the best athletes I’ve ever known, who told me about racism in the Projects neighborhood.

Connie Peterson, a ‘sister’, who told me the origin of my birth certificate.

Randy Wade, ‘The Sheriff’, my bodyguard who kept women away in college.

Pete Brown, ‘The Bruiser’, the man who introduced me to toughness on the basketball court when I was still a teenager.

Rudy Howard and Bobby Reeder, whenever I needed a place to sleep during my travels in the Americas, the door to each of their homes was always open.

Ray Craft, who warned me about a certain female and that I didn’t listen to. Roy is older than me.

Craige Moore, one of the purest shooters I have seen and my protector since school days.

Terry Garrett, my little brother who told me to keep my head up during hard times and who led me to the books of the Secret Doctrine.

Sam Wood, with whom I spent the most extraordinary, interesting and spiritual week of my life. An amazing singer, a voice of nature. She is also dedicated to Black History studies.

Troy Lacey, a close friend in Italy since 1992, and his wife Eva Zaplatilova.

Lucio Graciotti and Sarah M. Howell, who allowed me to mentor their son as a personal trainer and helped enrich my Black History library.

My ‘brother’ Luca Allegrini and his family, who rescued me when I had nowhere else to go.

Paolo Delfino and his family, who believed in me by entrusting me with their son Matteo, my little warrior brother, and opened their home to me.

The boys of the large Jesi family, in addition to Luca Allegrini and Paolo Delfino: Danilo Bordoni, Diego Cacciamani, Stefano Carletti, Carlo Delfino, Danilo Del Cadia, Giacomo Forconi, Antonio Gallucci, Emanuele Morresi, Andrea Nobili, Massimo Palmieri, Cristiano Pierandrei, Alberto Rossini (Lupo), the Rossini brothers, Angelo Sebastianelli, Marco Talacchia, Vito Valentino.

The Marchegiani family, who allowed me to understand the catering profession, learn about food preparation and the characteristics of wines and helped me regularize my documents in Italy.

Massimiliano Barbieri, ‘doc’, who has been my healthcare consultant for the last thirteen years.

Stefania Topa, who introduced me to massage techniques, allowing me to obtain a diploma.

Giorgio Del Papa, who gave me the information necessary to decide to operate on my hip.

Luigi Scarfiotti, who introduced me to the author of this book. Thanks to him and Michele Emili I met the golf buddies with whom I spend the most peaceful hours: Jacopo Carradori, Antonio Del Sordo, Tony Giuliano, Luca Lucchetti, Angelo Sorcionovo.

Special thanks go to the one I nicknamed ‘Bad Ass’, Paola Rivolta, for the enormous work done and the time she dedicated to reconstructing the events, venturing into the rabbit hole and giving life to this book. I have rarely met someone so helpful and dedicated to their work. There were many people who helped reconstruct this story, but ‘Bad Ass’ was the cornerstone, the one who made it complete, uncovering facts I had no idea about, truths hidden in buried archives from time. She has become, from the beginning, the fly on the wall. She did what no other person would have had the patience and perseverance to do, delving into every aspect of my past.

Prologue

Sarah was the daughter of cotton pickers, whose ancestors had cleared entire forests in the Mississippi Delta and tamed its restless waters by building levees, bringing crops and wealth to the white colonists who had settled in the land of the Chickasaw tribe.

Sarah was born on February 7, 1934 in Eads, west of Memphis in Tennessee, a small community that owed its name to Captain James Buchanan Eads, civil engineer and inventor of the first battleships that entered combat in the Civil War against the Confederates.

The town of Eads was established in 1888, when the tracks of the Tennessee Midland Railroad were laid through a village known as Sewardville. Hundreds of slaves had made it, some owned by the railway company, others rented from local landowners. For each of them that was killed or died, the company reimbursed the slavers the price of human flesh, certainly not the value of life.

Thomas Clay Owen had been the founder of that town. He, a merchant and justice of the peace, had been determined in the creation of some activities – a train depot and a post office – which had animated the small community.

The white inhabitants of Eads were mostly engaged in agriculture. Sorghum, tobacco and cotton plantations of which Owen himself was largely the owner, as was the case with the only cotton gin, located on the northwest corner of what is now Highway 64. The cotton gin was a machine made up of a set of metal wires and small hooks that separated the cotton fiber from seeds and had contributed to increasing productivity by cutting the price of the raw material and consequently incrementing the consumption of cotton on European markets.

An enhanced production that required new labor at increasingly lower costs and fueled the slave market, increasingly ousted native populations from their territories. As a consequence of this, Tennessee, which had been the hunting ground of the Indian tribes but also the place of advanced settlements of the native populations, became like the bed of a tumultuous river always in flood, crossed by continuous flows of men, women and children.

The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole passed through here along the Trail of Tears which was a mass forced migration towards Oklahoma but which was relatively small compared to the Slave Trail.1

Between 1830 and 1860, a million Blacks were forcibly moved hundreds of miles from tobacco plantations to cotton plantations, sold along the way, breaking up families, separating parents from children, leaving behind thousands of unburied dead, an open-air cemetery to which history, told for two centuries mainly by invaders, would not have given importance.

The slavers’ caravans came down from Virginia, along US 11 which, having entered Tennessee, ran parallel to the Holston River and, to the south, was channeled between the reliefs of the Appalachian mountains and then deviated westward.

Along the way, toward the murky waters of the Mississippi, other caravans from Kentucky and Missouri joined.

A multitude of human beings reached the river, along the path that had been traced by the natives and was now dug into the earth by thousands of chained men. The trail reached as far as Greensville, Vicksburg, Natchez, passing by rare burial mounds built millennia before, evidence of a history long before the European invasion.

Around the central nucleus of Eads, built on what remained of the old Sewardville, lay the territory called Gray’s Creek.

Gray’s Creek owed its name to the brothers James and John Gray who, at the end of the American Revolution, had obtained, in virtue of British officers, extensive territories on which, among other things, they had built the first house made of bricks in Shelby County.

The county was named from the first governor of Kentucky, war hero, Isaac Shelby.

Eads, Sewardville, Gray’s Creek, Shelby. The names of the colonizers had created a toponymy that had nothing to do with the history of the populations that had respected that land for millennia. A symbolic toponymy of the total, violent erasure of the culture and right to live of the native populations produced by white people of European origin.

It was understandable that Sarah had struggled to find stability in that land. Behind her there were ancestors of whom she knew nothing, who had not had the possibility of building families, dispersed, sold and bought by different owners, without the possibility of constructing houses that could contain memories, preserve continuity, the reminiscence of one’s origin.

Sarah, however, had, in her name, her story.

Sarah was a biblical name that brought to mind the principles of equality and the hope for liberation, but her surname, Gray – denoted, as for many other Black Americans, the belonging of her ancestors to a white owner – marked her. Gray’s Creek, the creek and more... of the Grays.

Sarah lost all ties to her place of birth when she was orphaned at the age of eight. From Eads she moved to the city of Memphis where her maternal aunt lived. It was 1942. The United States had recently entered the war after a fleet of Japanese Navy aircraft carriers had attacked the US naval base of Pearl Harbor, on the island of Oahu, in the Hawaiian archipelago. The attack, which occurred without Japan’s declaration of war, had caused the American population to feel emotionally involved in that conflict.

Memphis, like other cities, saw its social and industrial connotation overturned by the departure of men for the front and by the massive conversion of productive activities in order to become functional to military interests. The new workplaces were occupied for the first time by many women, however they did not affect, except to a minimal extent, the black population who remained on the margins of society, covering the worst paid and unprotected job roles.

On the other hand, discrimination was a connotation that appeared inextricably linked to the history of Whites in the United States. While Blacks became the protagonists of increasingly harsh and incisive battles, the Japanese present on American soil were interned en masse in concentration camps.

In that reality of marginalization, which was not affected even after the end of the war when the black soldiers believed they had redeemed, at least in part, their social position by having served their country on the front, Sarah had no way to emancipate her existence from poverty and segregation.

Although Memphis had episodes of early integration between racial groups, these remained isolated cases. The King Cotton Carnival, which for decades was one of the city’s emblems, saw only Whites participate disguised as ancient Egyptians. The Blacks, who subsequently organized their own carnival in opposition, used to pull the allegorical floats and, from the shore, the boats that transported the figures. The white population thus staged a double violence: it exploited the black population in subordinate roles and racially appropriated the history of ancient Egypt.

In the busy, colorful, noisy network of streets of the great city of Memphis, Sarah continued to carry with her the scent and the tactile memory of cotton flowers on the tips of her fingers and, intact but underground, the anger of those who are aware of not being able to have justice in a society in which segregation was still the law. Lynchings were usual and the air was filled with the smell of smoke from white crosses burned by members of the Klu Klux Klan.

Falling pregnant at just 16 years old was the natural consequence of accepting the role granted to her by the society on the margins of which she lived. And she found herself increasingly on the margins when, just three years after the birth of her first son Robert, Charles was born in 1953 and, then, in 1957, to a different father, Kathy and, two years later, Eloise. Men who remained at her side for some time, but did not support her in everyday life, nor in the effort of raising their children. Visitors, more or less occasional, to her room and her body. Thus Willie was born, to the same father as Kathie and Eloise, in 1961 and then Dorothy Jean in 1965.

The birth of her children forced Sarah to go and live on her own, finding shelter in a rundown house on the edge of Millington, east of Memphis, a wooden house, isolated, half hidden in the woods, without running water or electricity.

Only later she requested the assignment of a new home for her family. With that paper in her hand she was returning home on the night of a new moon when she saw the child.

CHAPTER 1

The hidden child

July 8, 1967. Perhaps this is the date, or at least it is the one that appears in the only document regarding my birth: a ‘delayed certificate of birth’, not a real birth certificate like that of my brothers, drawn up immediately in the hospital after giving birth, but a sort of certificate of existence written many years after the day I was born.

In reality, I will never be certain of the date. I can’t even be sure of the year. But it was summer, the sky was starry and the moon was new and a woman was walking barefoot in the woods along Pilot Road, just outside Millington, a few miles from Memphis.

What I am sure of is that when Sarah Gray lifted me off the ground and took me into her arms, I experienced for the first time the warmth of human contact and the sound of laughing and crying.

This is how I remember being born. Born from the earth, molded in clay and brought to a civilization that would forever remain foreign to me, in an embrace, without a dowry.

The house Sarah took me to was a precarious shack, wooden planks and earth, surrounded by nothing on all sides. She and those who, from that moment, had become my brothers and sisters lived there.

Robert, the oldest of the six, was sixteen. The youngest was Dorothy Jean, born in July like me, two years earlier.

Sarah’s children had three different fathers, but there was no one in that house who would have exercised any paternity. Neither with me nor with the others. However, I would never know who my father was.

Instead, I quickly learned about the woman who had become my mother. She was of few words, capable of decisive educational gestures. She was loving and understanding, but she was still a warrior used to fighting for her own survival and that of her family. She was particularly protective of me, or at least she was in the early years of my life. I was the child who slept with her, who sought and found knowledge of the world through her, the one who she protected beyond maternal love, for that sense of responsibility that is owed to those entrusted to you. She was the only door that allowed me to pass from what was there before, matter, to the present, artifice. But I don’t remember a hug from her.

In her house I was welcomed with distrust by most of her children. I had come from nowhere into their life, into their struggle to live and I distinguished myself from all of them even in my name. I didn’t have one.

Apart from Dorothy Jean and Kathy, the third daughter of the family who was ten years older than me, I couldn’t feel brotherhood with anyone, but even between themselves there didn’t seem to be a bond.

I have no memory of common rituals, lunches together, visits to church or visits from relatives. Nothing that resembled a regulated daily life. I have memories of children and young people who compared themselves with each other and with reality, through competition. My sisters fighting over the only pair of decent jeans. My brother’s gun hidden behind the bed. The search for Willie who didn’t come home for days. My sister Kathy, standing behind me, braiding my hair, talking about how they brought me home in a basket. The arrival of the man who slept with my mother, and me locked out of the room crying. The stomach burning with hunger, for days; with only water to try to ease the pain. The flies around the hole in the ground where we relieved ourselves. Sometimes, fights between us brothers.

The only discipline that my mother managed to impose on everyone was the one that most closely concerned me: I had to be invisible to the outside world and we all conformed. I was an illegitimate child and Sarah knew that my adoption would have been impossible given our economic and housing conditions. Hiding me was the only way she knew to keep me with her and to try to save me from a world to which, she knew, I didn’t belong.

My silence, that lasted seven years, was an integral part of my non-existence. It was certainly functional to it.

I grew up and didn’t speak.

I grew up and observed.

I grew up taking refuge in the woods that were beyond the road and I went further, towards the river, protected by the vegetation that became increasingly thicker as I got closer to the water.

Among those trees there had been my cradle and now there was my school; the one that would have shaped me physically and in character, which would have allowed me to save myself from excesses and then survive many of my friends. In nature and in my muteness there was the possibility of existing outside the system, of not being programmed in the early stages of life, of strengthening the mind.

In the woods I ran among the low branches of the maples, I climbed, I jumped, I lay for hours on the dry leaves, watching the weave of the branches become increasingly thicker as it became more distant, higher in the sky, watching the moon lacerating the darkness and the clouds, drawing intricate shadows on everything around me, leaving me intact.

I loved looking at the leaves and watching the snails leave their shiny streaks along the blades of grass.

I didn’t like snakes that were shiny and slithery, which appeared so smooth, yet to the ear like sandpaper, as they were heard entering the house. I kept my guard against them, armed with a small bow and some arrows, so that they wouldn’t reach my mother’s bed, just as I used to do with rats at night in the summer.

I liked pecans.

One day I had found a broken one, by chance, under a tree so majestic that it was visible from several miles away. I tasted it. The shiny, dark fruit was sweet. Looking up, I saw that the branches were overflowing with those nuts. With a stick I knocked down dozens of them and brought them home. I wanted my mother and my brothers to taste those pecans. I liked sharing my discoveries, but not everyone liked them.

Some of the pecan shells opened perfectly in half. On the water they floated like small boats and I used to take them to the river.

If only I had known about the steamers that transported our ancestors to the plantations along the Mississippi, I could have imagined a convoy, perhaps pretended to attack it to free my people, but, at the time, I had no awareness of history and I limited myself watching the nutshells drift away along the stream.