Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In the third and final book of Jess Smith's autobiographical trilogy, Jess traces her eventful life with Dave and their three children, from their earliest years together. Their adventures and achievements are interspersed with stories of her parents' childhood, her father's 'tall tales' and the eerie echoes of ghosts and hauntings that she has heard from gypsies and travellers over many years. Fans of Jess Smith will not be disappointed with her latest memoir, full of more unforgettable characters and insight into the travellers' way of life, a tradition that stretches back more than 2000 years and survives in the rich oral tradition of its people.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 436

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

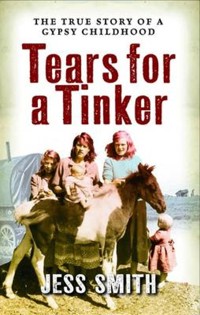

TEARS FOR A TINKER

JESS SMITH

was raised in a large family of Scottish travellers. This is the third book in her bestselling autobiographical trilogy. Her story begins with Jessie’s Journey: Autobiography of a Traveller Girl, followed by Tales from the Tent: Jessie’s Journey Continues and concludes with this book, Tears for a Tinker. She has also written a novel, Bruar’s Rest, and Sookin’ Berries, a collection of stories for younger readers. As a traditional storyteller, she is in great demand for live performances throughout Scotland.

First published in 2005 by Mercat Press Ltd Reprinted in 2005 New edition published 2009 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House 10 Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

Reprinted 2012

Copyright © Jess Smith 2005, 2009

The moral right of Jess Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978 1 84158 714 1 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 180 4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Set in Bembo and Adobe Jenson at Birlinn

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 MAMMY, WHAT NICE PICTURES IN THIS CAR

2 A LOOSE MOOSE

3 ON THE ROAD AGAIN

4 THE BIG HUNTER WITH HIS POACHER COAT ON

5 THE REAL LOCH NESS MONSTER

6 MACDUFF

7 THE CURSE OF A GOOD MAN

8 IS THERE ANYBODY THERE?

9 CHAPBOOK TALES

10 FATTY

11 POT HARRY

12 LIFE ON THE OCEAN WAVE

13 MY POETS

14 ENEMY AT THE DOOR

15 THE MORNING VISITOR

16 EWE MOTHER

17 THE FOX, THE COW, THE DEAD MAN AND THE WEE LADDIE IN THE BARREL

18 UNDER THE BLACK WATCH COAT

19 CURSE OF THE MERCAT CROSS

20 BAGREL

21 THE DAY OF THE HAIRY LIP

22 MY BROTHER’S SHARE

23 GLENROTHES

24 BELLS AND GHOSTLY CHAINS

25 A STREET NAMED ADRIAN ROAD

26 IN DEFENCE OF THE PEARLS

27 A BRUSH WITH THE LAW

28 ON THE GALLOWS’ HILL

29 MY SILENT FRIEND

30 STIRLING TALES

31 FAMILY LIFE

32 SPITTALY BANK

33 THE GIFT

34 MY TOP FLOOR HOME

35 YELLOW IN THE BROOM

36 JIP

GLOSSARY OF UNFAMILIAR WORDS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Coronation of the Gypsy King, Charles Faa Blythe

Camp of Highland travellers at Pitlochry

Isabella Macdonald, tinsmith

Nineteenth-century travellers at the berry-picking

Strathdon tinkers

A camp high in the hills

Tinkers’ cave, Wick

Jess’s father during the Second World War

Jess’s mother and father in 1942

Jess’s children—Barbara, Stephen and Johnnie

Jess’s husband, Dave

Jess with Johnnie and Stephen in 1983

Jess today

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Once more, to the army of workers who shouted at me, prodded and hugged me, and phoned my ears into oblivion: thanks forever.

To my family—well, what can I say?

To Mamie, for allowing me to share her father Keith’s poem.

To Douglas Petrie from Pitlochry for his river poems.

To Martha Stewart for all her help, and her belief in Scotland’s travelling people.

To cousin Alan for the Glen Lyon tale.

To Bob Dawson, my radji gadji, who never sleeps.

To Robbie Shepherd and his team for giving me a louder voice.

To Caroline Boxer of the Strathearn Herald, a wee worker.

To Alan Smith and family from Foggy.

To John Gilbert for allowing me to use his grandfather’s poem.

To the late Violet Jacob.

Special thanks to Charlotte Munro (sister Shirley), for always being there regardless—‘Ye cannae sleep us away’.

To Jenny and George—gone, but never forgotten.

To Tom, Seán, Caroline, Vikki.

Finally, thanks to the travelling people; my tinkers of the roads; the roots wherein I cleave.

Come all you tramps and hawker lads,

Come listen one and a’,

An’ I’ll tell tae ye a roving tale o’ sichts that I hae seen,

Far up and to the snowy north and doon by Gretna Green.

—all gone now.

I dedicate this book to my wee Mammy, who dedicated her life to her eight daughters

INTRODUCTION

Something niggled in my mind after I finished Tales from the Tent. It nagged and bothered me. I put on the kettle, poured a cup of tea and slumped down in that old tattered armchair of mine that refuses to die. Heidi, my cat of twenty or so years, curled into a ball of ginger and white fluff, licked her old, weak paw, yawned and settled for sleep. Then, as if a veil had lifted from my eyes, I saw in my mind what it was that so annoyed me. Remembering how brittle Heidi’s frame was, I gathered her into my skirt and darted back to the computer screen. Two tiny words leapt from the last page of my manuscript—‘The End’.

How could it be?! I hadn’t shared the stories of my parents’ childhood with you, nor some whoppers about Dave and my earlier wanderings. What about Glen Lyon, and Daisy thinking the Germans during the last war would steal the washing off the dyke, so she kept it in? What did she know of Europe? To her Germany was somewhere north of Inverness! And those fearsome ghost stories? How many times did I laugh at my father’s tall tales, I did so want to tell you about them. Och, nae way could we part, you and I, after all this time, without telling you of my nit-infested wild man who drove Mammy mental whenever we saw him on the road. The story of the row of turnips I pretended to some towny bairns was a row of rabbits just had to be shared, and so many more happy days. No, it certainly wasn’t ‘the end’.

Anyway how could I part from you? You’d become my good friends, fellow dog-walkers and tea-suppers.

So, gently uncurling the half-dead fluff ball from the threads of my skirt and laying her on a fleecy blanket beneath the radiator, I finished my now cold tea.

If you fancy another journey with me, settle back with your favoured beverage and let’s take once more to the road in: Tears for a Tinker.

The reason for the title is a story in itself.

My oldest son Johnny, then aged six, was not a happy chappie. You see, his wee pal Horace had died. This little pet, a goldfish his dad had spent loads of money trying to win at a fair, was our lad’s nearest and dearest in the entire world. He shared all his sorrows with that fish for the best part of a year, when one morning his heart broke at finding it tail-fin up at the top of its bowl. To take his mind off this tragedy we took the bus to Perth, the nearest town with toyshops. Christmas being round the corner, Perth was crowded and draped in sparkly lights. In the centre outside Woolworth’s, Johnny saw a poor travelling woman with four bairns round her coat hem. All the wee ones were in tears. Poor gentle-hearted Johnny said to me, ‘Mammy, what is wrong with them bairns?’

‘I’ll tell you when we get home,’ I told him, adding, ‘now stop staring at people.’

That night after supper, with Horace laid to rest in a matchbox buried underneath a soft patch on the washing green, my little boy brought up the subject of the traveller and her sad, wet-eyed children.

I knew the woman, not personally, but recognised her from her kin, who usually winter-camped in bowed tents near Lochgilphead. Sometimes they favoured Double Dykes. This was a large boggy field on the outskirts of Perth, and now, thanks to the efforts of hardy travelling folks, it had been turned into a properly-run caravan site.

‘Well, my lad,’ I said, sitting him on my knee and squeezing him gently, ‘that poor woman had no husband. Those bairns didn’t have a daddy like you to bring in money for food.’

He asked where their dad was, but at six-years-old his young ears were not ready to hear that the man was burned to death in a warehouse fire in Glasgow. I simply said that he died of a bad illness. I know telling lies is not a good parent thing, but Johnny was a sensitive child.

His little eyes widened, and I could see the brain cells painting a picture of kids without a dad. I went on, ‘those tears were caused by their mother rubbing onions around their eyes to make them cry.’ This seemed to horrify my child. He jumped off my knee, eyes wider than ever in disgust and wonderment. ‘How could a mother do that?’ he raised his voice. I looked into his little reddened face and calmed him down. ‘Son’, I assured him, ‘no mother loves her children more than a travelling mother, but those kids had to beg, and that was her quick and authentic way of doing it. Long ago—well, if after the last war was long ago—that woman’s menfolk would have owned tinkering tools to fix pitchforks and knives, pots and pans; in fact any kind of broken metal would have been sorted, and that would bring in money. She would have had a job if it were the olden days. They used to be called tinkers because of the noise their tools made as they carried them on horse bags or wee bogeys, and later, prams.’

He didn’t understand much of what I told him, nor the word authentic, but he got enough of the explanation to learn that onions make you cry, and crying brings caring folks to part with a few coppers. ‘If that mother had begged for money, folks would have looked the other way. The tears unwittingly made them give generously. Tears reach our souls. And I know that for every person who gave, she would have blessed them with a prayer to God.’

Silence followed, and both Dave and I could see our wee boy deep in thought. In time he went into the bathroom, and came out with tears flowing down his small face. ‘What in heaven’s name is wrong, laddie?’ asked his concerned father, whilst I was busy feeding Barbara, our youngest, who was three at the time.

‘Those wee tinker bairns without a daddy made onion tears. Well, I have cried some real ones for them.’

Johnnie was cradling in his hand a photograph of his dear departed Horace.

When our children grew older, I would often tell them stories of my own tinker childhood, and to this day they are proud that mother belongs to a cultural background rich in ballads, stories, and with a lifeline going back two thousand years.

Well, where will I start? Yes, let’s go back to Crieff, just after Stephen, our second lad, was born. We were living in a rented flat, part of a large Georgian house. If you have refilled your cup, then let’s walk back again, back down memory lane.

1

MAMMY, WHAT NICE PICTURES IN THIS CAR

Davie had a succession of jobs, but all paying next to nothing, and this meant very little money for anything other than the bare necessities. My in-laws, Margaret and Sandy, were super at keeping the kids in clothes, sometimes paying the odd bill when we struggled with other debts. Sandy worked at Naval Stores near Almondbank, three miles from Perth. In his spare time he excelled as a poulterer for John Lows, fishmonger in Crieff. Margaret had taken jobs cleaning hotels and offices. Davie had a younger brother, Alex, who was a wee brain-box. Much to his parents’ delight, he was always studying, head down in books. Alistair had been their oldest son, but at twenty-one years old, while serving in Germany with Her Majesty’s Royal Engineers, he was killed by an express train. Margaret never got over the loss of her boy, avoiding any conversation that might open her wounds. In her own way of dealing with his death, she kept quiet and to herself.

I sometimes wondered if I was good enough for her son, me being from travelling stock, but she made me welcome from the first moment we met, and we stayed friends until her death of cancer many years later.

Mammy and Daddy had uprooted themselves and headed for Macduff on the Moray coast. A picturesque house nestled at the top of the town became their home, and if memory serves me right the street they lived on was Patterson Street. Macduff is built on a steep hill, so the views of the ocean from that house were spectacular. When we visited them for the first time I didn’t want to go away, it was so fresh and beautiful. Even the sea-gulls had a kind of regal glide to their wings.

Dave and I bought a cheap scrap-heap of a car for the journey, a white Ford Popular it was, from a ‘This is a bargain, honest, folks’ mate. From Crieff to Macduff is 140 miles, and how we survived that trip was a miracle to say the least. Round about Perth it became apparent that the vehicle had a few more openings than just the doors and windows. Johnnie sat alone in the back, and kept telling us he could see brown and black ribbons, and what a bonny picture they made at his feet, also that he wasn’t comfortable due to a lumpy bit on the seat. We ignored him, putting his remarks down to the vivid imaginings of a toddler. I sat in the front with Stephen on my knee. This was before seat-belts, and when I think on how dangerous cars were back then, I’m certain a higher being was watching over us. Outside Perth, Davie heard a rattling sound and pulled over to investigate. It was then he discovered that Johnnie’s ribbons were in fact the road beneath us. Our wee laddie had been staring down through a gaping hole in the car floor, which had given way not long into our journey. The rattling sound was another problem; the exhaust had decided to part company with us, causing the most horrendous roar all the way to Macduff. How the police didn’t get wind of our travelling beats me. When we at last arrived at our destination, Daddy was horrified by the state of our transport, and flabbergasted the car had made it.

However we soon forgot about the car, because I was so happy being near my precious Mammy. After looking over her new home I thought, ‘she’ll be content here’.

This was the first time in thirty years that my parents had slept in a bed that didn’t need folding up in the morning. Daddy felt uncomfortable at the change, and so spent most of his time scanning the horizon of the sea from a high wall circling the fine garden, like a mariner with a hand shading his eyes, rather than sitting inside at a nice warm fire. I must have got my travelling blood from him. Mammy, on the other hand, was in her element. She had her very own sink, oven, bath, washing line and much more. At long last she had arrived at her castle—a wee queen. She discovered, much to her delight, she had green fingers, and grew herbs, flowers and shrubs. She baked cakes. Boiled up, not just berries for jam, but countless pans of other culinary delights to store in large jars, which she delicately labelled and stored in the larder.

Meantime my younger sisters, Renie and Babs, took on jobs living as any normal lassies would do, and never mentioned their rich cultural background as travellers.

Daddy still had his health, and his spray-painting equipment that he used for contract work. He started up a small business, earning enough to live a comfortable existence. He furnished the house with all that was needed, and soon settled into the friendly neighbourhood. However, when asked if he was now a ‘scaldy’, he would reply, ‘Nae way am I a hoose-dweller. I’ll aye keep yin eye on the road, another yin on the sky.’ What that meant was that if the mood and the weather suited him, he would go.

By then I couldn’t have seen Mammy going with him, though. She loved her bus-travelling days, no doubting that, but now, older and stiffer, she’d settled for her cosy wee hoose. Anyway, she’d seen enough of Scotia’s bit fields and wood-ends in her lifetime. There wasn’t a B-road she didn’t know, nor a landowner she cared to know; a lifetime as a gan-aboot for my dear Ma was well and truly over.

The only worry she had was that Daddy’s habit of leaving doors open at night stayed with him. When a boy, because of claustrophobia, he’d throw open the tent flaps at night, and according to Granny Riley they’d all be near frozen stiff. Even the bus door would get drawn back; frost-covered eyebrows he’d wake up with many a winter morning. So once more, even although he’d found a spacious bedroom to sleep in, the daft gowk insisted on leaving the house door ajar. Nothing scunnered Mammy more than thinking a wee mouse was inside her larder, scoffing all those cheeses and cakes she stored so meticulously. Many a time she scolded him, ‘Charlie, man, I’ll feed the mice-droppings tae ye if I find them at the fit o’ ma press. Honest tae God, I’ll pit them in yer stew and tatties.’

He in turn would say, ‘I dinna want that bloody door locked if a fire breaks oot.’

‘Away an’ no be so silly’, she reminded him nightly. ‘The fire’s cinders and ash. Anyway, the safety screen is on.’

We couldn’t drive home after that first visit because Davie was pulled up by the Banff police on account of our noisy exhaustless car. Banff is only a mile from Macduff, separated by a grand bridge. There’s a story from those parts about a certain fiddler I’ll share with you soon, but not until I’ve told you about our car. Driving along the road, Davie noticed he was being followed by a police car. The officer who pulled him over had a wee look under the vehicle, and when he stood up said to Davie, ‘Div ye ken there’s a burst spring in that car, loon? It’s a’ down on the one side.’

My poor husband, who had not long had his driving license but acted like he knew all about motors, said, ‘Och no, officer, there’s nothing wrong with it, it’s only a wee-er spring than on the ither side.’

The policeman took off his helmet, knelt down and said, ‘Listen tae me noo, loon, an’ no be makin a fule o’ me. I ken enough aboot motors to tell when one has a burst spring. Now follow us and we’ll gie this heap a guid going over.’

Well, to cut a long anxious story short for Davie, they told him to come back after two, and they’d have it inspected properly. Imagine his horror when he found his white Popular Ford sat at the rear of the yard, with a sticker on it saying ‘non-roadworthy’. The lumpy bit that had made our wee Johnnie so uncomfortable was in fact the broken spring, held in place only by the metal frame of the back seat.

A visit to a scrappy left us with three pounds and car-less. Once again we were reliant on some kind soul to take us home. This time my Uncle Joe offered to take us, and boy, were we grateful.

2

A LOOSE MOOSE

Now, the mention of Mammy going on about mice made this memory come vividly back. I can’t remember telling you about the time when we lived in the Bedford bus and my older sister Shirley, seething with thoughts of revenge, brought back a pet from the tattie-field.

This is how it went:

We had settled up for the winter in Tomaknock outside Crieff. It was tattie-lifting time and all hands were to the fields. All except Mammy, that is, because she had enough to do with Babsy, her youngest and not yet school age, and Janey who was working as a shop assistant in Scrimgeours (Crieff’s high class department store). Renie and Mary were at school, but I was a fine tattie-lifting age of nine. I had an exemption certificate signifying that I was fit for hard work. Well, it didn’t really mean that, but Daddy always made me feel a big lassie when he said it did.

In the fifties, traveller children were allowed to attend harvests as long as they attended school when they were finished. However, just in case some lazy travellers ignored the harvest time and kept their kids off school without working on the tatties, inspectors would randomly visit campsites and tattie fields checking for shirkers. I might add that their search was nearly always fruitless, because travellers knew just how much of a difference tattie money made to a cold winter existence. If my memory serves me right, these inspectors were known as the Spewers—this meant when folks saw them coming, it made certain bodies sick.

Shirley and Chrissie had been arguing all that morning, something to do with a Teddy-boy apprentice named Bobby. This said lad, with a headful of thick, sticky Brylcreemed hair, hadn’t decided which of my sisters he wanted. Sixteen-years-old Shirley had already made up his mind for him, and didn’t like the fact Chrissie, then nineteen, was homing in on her beau—so she threw a bowl of porridge over her.

Mammy slapped the both of them and refused to pack sandwiches, saying, ‘Bloody stupid buggers, it’ll serve ye baith right for filling yer heads with men when there’s a ton o’ tatties needin’ lifted. Now, if you want food then walk back here, an’ I’ll have soup ready for dinnertime.’

‘Mammy, for the love o’ Jesus,’ exclaimed Shirley, ‘the farmer’s fields are three miles from here.’

‘Don’t blaspheme! There’s no so much as a nugget o’ shame in ye.’ Mammy hated to hear the Lord’s name uttered in vain and warned Shirley to mind her tongue.

‘What do you expect from a dung-face like her?’ laughed Chrissie.

It was all my poor mother could do to stop them from cat-fighting, so rolling up a wet dish-cloth she gave them a nippit wallop into the back of their legs. It worked, as each of them ran off to await the early morning transport laid on by the farmer to collect his workers.

Chrissie heard the tractor and bogey coming, grabbed a welly under each arm, and called out to Mammy that she’d get a certain tractor lad to drive her home at dinnertime, but that Shirley would have to walk. Mammy gave me and oldest sister Mona sandwiches for the day, knowing the farm wife would supply milk, and ignored her haughty pair of daughters who were staring daggers at each other. Once on the bogey we all found a space to sit between thirty or more Crieffites, while the driver made his way to where the tattie field lay ready to be churned by mechanical diggers and flattened by a hundred pairs of eager feet.

The farmer guided us to our set ‘bit’ for the day, while we scooped up enough tatty skulls (potato-lifting baskets) scattered around from the previous day’s work. I called out hellos to a family of Burkes (distant relatives to my father), especially to Elly who was nine like me. She was great fun, and not afraid to play the silver birch game at break time. Growing next to the field, these slender, thin-barked trees were ideal to shin up. When you reached the top, there was sufficient pliability in the trunks to bend them down, and when they couldn’t bend any further you just let go, landing like Tarzan on the next tree along. A whole wood could be covered this way. Anyone who touched the forest floor with their feet had to fall out. This was just one of many games we traveller bairns had devised to play with Mother Nature. No one ever broke a tree, or if they did then it was understood they carried too much weight and couldn’t take part in the game.

We could do a fair share of showing off as well. Once, when I had been at the berries in Blairgowrie, I told a lot of scaldie bairns who were bothying at a nearby farm to lie still and no’ frighten the row o’ rabbits at the brow of a hill. Stupid gowks, did they not lie stiff for an hour, not moving or saying a word. If a shepherd hadn’t appeared when he did, shouting to them to be off, they’d still be there. No, they weren’t rabbits, it was a row of neeps (turnips)! Anyway, let’s get back to the story of my sisters, feuding over a Teddy-boy.

Chrissie settled onto her spot at the far end of the drills, with Shirley downwind. Shirley swore if she so much as smelt her archenemy on that day, she’d throw worms at her.

The hard back-breaking day dragged on, with every person on that field praying that the earth would throw up a giant boulder with enough bulk to render the digger powerless. But with the digger not hitting a single stone and stopping to give us a wee respite, the work was relentless. Up and down, down and up, no sooner were the skulls filled and emptied when up came the digger again. At piece time, all that could be heard was the munching of sandwiches and slurping of tea. This was provided by traveller women, though first they always carried on working their husbands’ patches along with their own while the man made a fire and boiled the kettle.

Shirley asked me for a piece of bread and of course I gave her some, even though I knew I’d not have enough to get me through the day. But she and I were close, and what sister could eat while the other had nothing? Elly’s mother Jean-Ann gave us soup, which helped. However Chrissie wasn’t so fortunate. She’d found no generosity coming from the folks at the end drills, in fact these craturs refused to share a conversation with her, and I wouldn’t blame them. She had a face like fizz, and a brow furrowed like the same drills she was lifting tatties from. But things were to change, when a very handsome tractor driver appeared to whisk her off for dinner. He offered to take Shirley back home too, but Chrissie warned him not to, or else. As I watched my older sisters, one on the back of a tractor, chest out and chin upwards in defiance, the other squeezing dozens of fleshy worms in her fists, I thought only one thought: the bus was going to be the scene of a war of the Amazons!

At long last the day came to a finish, and I can tell you there is no better sight for a tattie-lifter than a digger man turning his vehicle homewards.

We clambered onto the bogey, every bent-backit one of us, from teeny wee weans to decrepit auld bodies, praying the tractor driver would do his best to avoid the dozens of waterlogged pot-holes in the long farm-track road. He didn’t though, the blasted sadist! Middle-aged women, not afraid to speak their minds, screamed the air blue, but from the safety of his tractor seat he grinned as we rolled and joggled from side to side.

At long last we jumped off the bogey at the bottom of Tomaknock Brae. Shirley pulled on my arm for me to look at something concealed within her trouser pocket. Gingerly I peered in, and near on died when I found a totty snout-faced wee mouse staring up at me.

‘What in blue blazes are you going to do with that? Let it go! It’s cruel to keep a helpless thing.’

‘Shut up, I’m only going to put it into Chrissie’s bed for a night. In the morning I’ll set it free. That’ll sort her to eye her own men and leave mine alone.’

‘I thought you were going to pack worms into her pyjamas?’

‘Well I was, but when the digger threw this wee lad into my skull I thought it would have a better effect. Dae ye mind when one ran intae her knickers while she wis peein under the railway arch at Ballinluig? God, did she no half shoot up ontae the track. If Daddy hadn’t been there, a goods train heading tae Pilochry would have flattened her—no way would she have won the “Miss Logerait” beauty contest if it had. Mind you, if I wisna in bed at the time with a broken shin, it would have been a forgone conclusion who the winner would have been.’

Before I could say a word on that matter, a certain painter and decorator’s apprentice with a stiffened head of jet-black hair came walking towards us. It was Bobby.

‘Hello, darling, are we goan’ dancin’ the night?’

Shirley blushed, not at his request but at her grubby tattie clothes. Still, clothes don’t maketh the man—or, in Shirley’s case, the woman. Anyone who ever met my sister will tell you her beauty was awesome. Flawless complexion, hour-glass figure, shiny black hair, perfect height and sea-green eyes. Oh, indeed a beauty. And boy, did she flaunt it.

‘How could I be such a twit to imagine he’d look sidey ways at weasel-face Chrissie, there’s no comparison,’ she reminded me, then called to him, ‘I’ll see you at seven,’—totally forgetting that helpless cratur which shivered in her pocket, unaware of its fate.

Chrissie was busy chatting with her tractor man and making her own plans for the evening. Mona too had a fancy-man, but with her flair for finding rich guys she kept him a secret. Mind you, I noticed the farmer’s son spent more time giving her denim buttocks the eye than those of any other female tattie-lifter.

The three of them dashed into the bus to see what Mammy had cooked for supper, before the battle of soap and towels took place.

Mammy was in a great mood, because a nice lady had presented her with a massive box of the finest bed-linen. This person was in the throes of emigrating, and wondered if Mammy wanted her bedclothes. What kind of a question was that for a mother with eight lassies?

Chrissie and Shirley, who had by now settled their differences with a silent truce, lifted the great big box of bed-linen and sat it to the back of the bus, where Mammy would later put it under her and Daddy’s bed, in a large storage box used for storing all the family’s blankets and sheets. Daddy never let on, but we think he got it from an undertaker—still, it did the job.

Supper was mouth-watering, stovies and onions with stewed rhubarb and custard to follow. Mary and I did the dishes, while the she-devils made themselves into Marilyn Monroes and Gina Lollobrigidas. I loved watching them. Silk stockings would have been a bonus, but no one could afford them, so my sisters, being the Picassos that they were, improvised by very carefully drawing charcoal lines up the back of their legs. They looked just like stocking seams. Except for Mona, may I add. She had the real Mackay. She would save every penny until she had enough to buy them. When she dressed, it was an art form like no other. For a start, she never pulled on stockings without having cotton gloves on to avoid snags. Her shoulders were covered by a towel when she powdered her face. It would have been terrible if one particle of powder should come to rest on those fine silk blouses she often wore.

Now, I know you’re having a hard time imagining that all this went on in a single-decker bus, but believe me it did. Not only that, but Daddy listened to his wireless through all the high-pitched chatter and Mammy told stories to her wee ones.

Now let’s get back to another wee one—a certain mouse, to be exact. ‘Where did Shirley put it?’ I thought, as I watched my older sister saunter off arm-in-arm with Bobby, the Brylcreem king.

I quickly checked Chrissie’s bedclothes, but they were neatly folded where she’d left them that morning. I didn’t say anything to Mammy or anyone else; not wanting my sister to get a row and knowing that she would when Mammy found out. After a fruitless search, I gave up, thinking she’d disposed of the wee timorous beastie into a field of cropped corn next to our winter stopping-ground, and I forgot the matter.

Next day the lassies were all chatted-out by the lads and tired after their gyrating on the dance floor. The day went on at its usual pace, a replica of the previous one, until while shinning birchies I tore a great lump of material out of my trousers, and was presented with another pair by the farmer’s wife. She had no females in her household, only young ploughmen—what a sight I was in my nicky tams!

Within three weeks, Mammy began complaining about a scratching noise beneath the bus somewhere. This was not unusual, so Daddy set some traps. The noise continued each night, driving my poor mother batty. Eventually, unable to stand the constant scratching, she sat bolt upright in her bed and screamed into the pitch dark night that we must all rise ‘oot o’ our pits and search for the moose!’

Damp matches were thrown all over the bus as Daddy tried to light some candles, tutting and moaning about broken sleep.

Suddenly I froze, and the same thought must have been flooding Shirley’s mind, because she gave me a nudge. What if her wee mouse was hiding in the bus?

‘What happened tae the moose?’ I whispered.

She whispered back in my ear, ‘I don’t know. All I remember was taking off my trousers and laying them on that box of linen.’ Her face drained of colour. ‘Oh, oh, bucket o’ shit, are you thinking what I’m thinking?’ she said, tightly squeezing my arm.

‘I hope for your sake those fine Irish linen sheets are intact,’ I told her, unfolding her fingers from my pinched flesh.

Mammy threw up the mattress and opened her blanket box. ‘Hold that candle down there,’ she ordered Daddy. I swear, on my Granny’s low grave, I have never seen such a sight; no wonder Mammy shrieked louder than the Banshee. Piled high inside the box were mounds and mounds of shredded sheets, blankets and eiderdowns, and curled in a corner was a terrified wee mouse with a dozen and more tiny weans, all squeaking and squirming.

Mammy never knew it was Shirley who caused that catastrophe by introducing a pregnant mouse to our home, but I knew, and boy, did I put the tighteners on her when I wanted something!

3

ON THE ROAD AGAIN

Now, back to the pokey flat in Crieff where Dave and I were living. The postman made me cringe each time he pushed mail through the letter-box—with me feeling trapped behind four concrete walls and a heavy oak door, it seemed to me that he was a prison warder having a peek.

Davie was born and reared in a house, how could he possibly understand my anguish? The poor man had enough to do keeping down a job without having to take my constant nagging about how unhappy I was in that house. ‘Listen pet,’ he assured me at nights when I tossed and turned in bed, ‘you have more to think about nowadays than yourself.’ He’d point across at our sleeping infants, and I knew what he meant.

In all honesty, though, as days turned into weeks, I began to hate my basic but comfortable home, and could hardly wait for morning, when my little boys were rushed into their clothes and popped into the pram. Like a miniature gypsy wagon, that pram was crammed with enough food and drink to last all day, as I got as far away from the four walls and into the fields and woodland surrounding Crieff. Stephen’s baby milk was wrapped in tin-foil and nappies to keep it warm. When we stopped, out would come blankets for the kids to lie on. Then my shoes would be discarded, as Mother Earth and my feet joined again. It was as if I was retracing my steps to old tinker ground.

Listening to the different birds singing to each other, it seemed as if they were including me and my wee lads. I’d sing a lullaby to my tiny infant, then when he was asleep I’d teach Johnnie how to tell the difference between trees and bushes. Tell him tales of the Tree people who lived under bark, and Giant Mactavish who spent all his two hundred years living in the forest fighting off the Smelly Sock frogs. (When I recall how his big hazel green eyes lit up at those stories it makes a dull day disappear.)

Rain or shine, it made no difference, just so long as me and my little half-breeds could escape to the open spaces. When the sunshine of summer shone in cloudless skies, going back to the house was more than I could bear. Selfishly, I’d leave my wristwatch at home, and one day, when we eventually arrived back, it was a very angry, hungry husband who confronted me.

‘Jess, I can hardly work for worrying about you.’

‘Why?’

‘Trekking lonely byways with my wee sons, that’s why.’

‘They’re fine; do you think I’d put my boys in danger?’

‘If you’d come down out of your silly cloud for one minute and listen to me. What if one of them got sick or something?’

‘Davie, travelling people live like that, we cope with everything, even sickness.’

My stubbornness hit a raw nerve, he thumped the kitchen table so hard all four legs bounced off the floor. Cups wobbled in their saucers as sugar scattered between them.

‘I am not a traveller, though, and these are my sons! And by God, I don’t want them dragged around the countryside because their stupid mother won’t let go of a dead lifestyle. Now stop it and get a grip.’

That night I wrote the longest letter of my life to Mammy.

Davie and I were like strangers after that night, with an iron atmosphere between us. Sandy brought a garden swing for Johnnie and Margaret gave me a Bero home-baking recipe book. Strange to imagine me being a good baker, but with my wandering curtailed I had to do something. Davie saw I was trying to adapt into scaldy life, and in time our marriage did strengthen again.

Then came the letter from Mammy.

Round the corner from her house was a wee low-roofed cottage, Daddy knew the old man who lived there. He, getting too elderly, had decided to move over to Aberdeen with his niece. The rent would be affordable. ‘Did we want to come up to Macduff?’

I was like a bairn on a Christmas morning. ‘Oh Davie, please say we can go.’ The thought of living in a new place beside my parents was drawing pictures of wonderful excitement.

I had deep pangs pounding in my breast. Would Davie, who was a Crieff man through and through, say no... or maybe yes. I watched his face, then he said, ‘I’m away out to think this over.’

Hours passed, and there was still no sign. It made me think my long-suffering husband was not ready to up sticks and go far north; fifty miles north of Aberdeen, to be precise. However, just after midnight I heard his key in the door. If extra persuasion was needed I’d baked a thick chocolate cake.

‘Well, lad?’ I asked, pushing near half the cake under his nose, and waited on his answer.

‘Yip!’

I could hardly contain my excitement, because when Davie said ‘yip’, it came without conditions. We were leaving Crieff and this nightmare prison of a house.

That night we cuddled and laughed with excitement at our forthcoming new ground.

‘My birth sign is “Pisces”, the two fishes. Macduff is a fishing port. All the signs are there—we will be happy.’ I was heart-sure. Davie joked, reminding me his sign was Cancer. ‘Plenty of them crawling among seaweed on the shores of the Moray Firth,’ he said, and tickled me, pretending to be a crab.

We were both only twenty-one, a lifetime spread out before us. Macduff, I was certain, would be just the first place of many more.

Sandy and Margaret were heart-sorry to say goodbye, especially as we were taking their only grandchildren from them, but offers to visit would soon find them not far behind us.

4

THE BIG HUNTER WITH HIS POACHER COAT ON

I have a wee tale to share with you before we all take ourselves up north. John Macalister, a half cousin of mine who had promised to flit us in his wee van, was helping with our packing one night when he brought in a large rabbit some mate of his had trapped. I told him to take it away, because I’d no stomach for skinning or gutting. Anyway, all my cutlery and cooking utensils were packed in boxes. Over a bottle of beer, he and Davie got talking about poaching and trapping and so on. When John left, Davie said. ‘I think I’ll go out for a wee turn at the poaching.’

‘What?’ I asked.

‘Catch myself a goose.’

‘Davie, did you not hear me tell John all my utensils are in boxes?’

‘Dad would pluck and skin it, if I caught one, and Mother would cook it. We could call it our going-away feast from Crieff.’

This was my husband’s one and only attempt at goose-stalking.

Old Tam, a neighbour, had given Davie a long, heavy wool coat some time ago.

‘A richt poacher’s yin,’ Tam joked, showing Davie all the concealed buttons and hidden pockets. Davie thanked his neighbour, but as he never considered wearing anything other than trendy Beatle jackets, he put it away, not intending to be seen in it. So imagine my surprise when he unearthed this sinister-looking garment to go goose-stalking.

All that day, fog and damp air covered the countryside. Geese and ducks could be heard flying above the blanket cover of mist. ‘Surely I’ll get myself one, there’s hundreds up there,’ he said, pointing upwards, the poacher’s coat hanging loosely over his frame.

Before I could close my half-opened mouth he was gone, swallowed up by the mist that swirled round his ankles, billowing up into that coat. All he left behind was the eerie noise of his footsteps on the pavement outside our soon-to-be-vacated house. I imagined him rounding a corner in the street. ‘My God,’ I thought, ‘he’ll frighten folks to death. He looks like Jack the Ripper.’ One glance at the mist, tinged orange by the street lights, and the door was slammed shut, and my kettle boiled for a nice warm cup of tea.

For a moment I peered through a slit in the kitchen curtains, convinced he was joking and that I would soon hear his knocking on the door, but no sound came and I began to worry. Feeling a wee bit uneasy about the thick, ghostly mist outside, I closed the window I’d left ajar, and then ran through the house, drawing the curtains. Johnnie pushed his tiny arm into mine and asked for a biscuit. I gave him several, along with a box of Lego. Then, when Stephen filled his nappy, thankfully concerns about Davie diminished while I busied myself with the bairns. The hours passed slowly, and my boys were long bedded and asleep when those familiar footsteps brought my man home. ‘Is that you, Davie?’ I asked, before opening the door.

‘Woman of the house, open the door and let your hunter in,’ he joked.

‘Have you caught a goose, then?’

‘Have I indeed. Feast you eyes on this big juicy fella.’ Davie threw open his poacher’s coat and rammed both hands eagerly inside the hidden pockets. From one he took out his father’s priest (salmon thumper), and from the other a big, brightly-coloured, plastic, DECOY DUCK!

The sight in front of me I can only describe as unbelievable!

The fog had turned to rain and soaked him to the marrow. Exhausted, but still smiling, he made me promise hand on heart not to tell a living soul what had happened—that he had seen the duck sitting in a field and lay on his belly for ages stalking it. When he decided that it must be an injured bird, he jumped up and charged. Not until its head went one way, and body the other, did it dawn on him what it was he’d been stalking in thick mist as he crouched for hours on the freezing ground.

The poacher’s coat was handed in to big Wull Swift, a real life rabbit man. He, standing well over six feet, would be better suited to its size.

I never was one for breaking promises, so only after getting my red-faced husband’s permission have I ventured to reveal to you the tale of ‘The Big Hunter, with His Poacher Coat On.’

5

THE REAL LOCH NESS MONSTER

Stories of hunting, shooting and fishing were common among travellers while I was a bairn. Depending on how they were told, certain tales stayed vividly cemented in my head. This tale I wish to share with you now is about the most feared hunter in the whole world, and for two reasons it has never left me. One is the legend that is intertwined with it, and the second is its theme of greed. Greed is a monumental sin, but one that can grant you the gift of immortality if the old Devil likes you for it.

Are you one of those who believes in the Loch Ness Monster? If you are, great! If not, then perhaps after this story you’ll be of a different mind. I leave it entirely up to you, my dear friend. Sit down, and I hope you are near a pond or some other stretch of water, though it would be far better if you were sitting on the shoreline of Loch Ness. Never mind where you are, just let me paint the scene.

Around three centuries ago, Peggy Moore, a heaving giant of a woman, lived in a tent on the side of Loch Ness with her husband and son.

Quiet folks living over in Drumnadrochit kept well away from Mistress Moore’s abode. Not because her family were tinkers, but simply because folks were terrified of her brute strength. For around the expanse of the loch it was well known that she was as uncouth and unkind a woman as ever breathed good air. Her long-suffering husband and son were kept back-weary working to feed and clothe that awful brute of a woman. She was not born with her huge bulk—oh no, it was sheer unadulterated greediness alone that was responsible. Folks said, as they were wont to do in wild and isolated places of Scotland, that she was the offspring of a witch’s womb. They further said her husband had been put under a spell and enslaved to do her bidding. And adding to this household, the result of a single passionate night when the hypnotised husband was robbed of his reason, came the son.

When rising in the morning Peggy ate her way through pound upon pound of thick milky porridge and loaves of crusty bread. Mid-morning, she’d thump the bare earth outside her canvas home screaming for more food, and this, sad to say, was provided by her deathly-pale and emaciated kin.

‘Get me meat, ye useless objects,’ she’d howl at them, ‘work and work until I have my fill.’

And this the sad pair did. Cutting trees and selling firewood from early morn until sundown, they chopped and sawed until exhaustion took over. Then, before falling onto their small, narrow, straw-filled mattresses, they handed over every penny they had earned.

This Mistress Moore was not just a greedy bisom—oh no, she also had cunning in her bones, so she did. Because some of the hard-earned money went into a purse she hid under a horse-hair bed, to be saved for the beef market. And on the day our tale unfolds, farmers were congregating over by Castle Urquhart to sell the best cuts of prime meat.

With a thump and a kick she sent her menfolk off earlier than usual that morning, followed by a sharp warning not to come home until the stars were sparkling in the sky above.

Keeking from her tent door, she watched until the men were gone into the forest before counting her money. ‘Oh man, ye look fair braw, ma bonny bawbees, I’ll git maself a rare bag o’ the best juicy meat today, oh a grand day, tis this.’

No sooner had she lifted her massive frame—which, it may be said, weighed half a ton—onto two swollen feet, and pushed open her tent door, when two shepherds came coyly by.

‘Hello tae ye, Mistress Moore,’ they said, pulling cloth toories from their heads and making sure there was enough space between them and her tent. It was usual for the said woman to throw a punch and ask questions later. Not this day, however. Hardly glancing in their direction, she covered her shoulders with a shawl of grey wool, bigger than any normal family blanket, and began to waddle off down the road.

‘Mistress, we have been having terrible times wi’ a giant cat-like creature,’ one said, still clutching his headgear and keeping a safe distance behind. The other made up to her and tried to get her attention by overtaking. Not one bit did she tolerate such intrusion, and lashed out at the poor fellow with an elbow to his chest. Several feet in the air went the poor man, landing hard on the rough shale shore.

The other shepherd stopped to assist his friend, shouting after Peggy Moore, ‘it can rip a calf from its mother and crunch through a sheep’s skull with one close of its jaw. We canna find it, so you had better mind yer back, tinker woman.’

The earth stopped shuddering as she halted her footsteps. Only her head did she turn to dart evil glances at the men, who stood there with plaidies covering their shoulders and cromachs to hand. One look in her direction, and the three accompanying sheepdogs curled around their masters’ feet like earthworms.

‘I hiv nae fear o’ ony livin’ creature.’ She lifted a fist into the air.

‘But Mistress Moore, this is a demon cat wi’ the power of a lion, the jaw o’ a tiger and the stealth o’ a panther. Tak’ care an’ keep a fire burning in the darkest pairt o’ the nicht.’

‘Let it dae its worst. If it has the courage tae come within a hundred feet o’ me, then little does it ken Peggy Moore.’ With those words ringing over the still waters of Loch Ness, she rounded shoulders, laughed loudly like a witch cackling through the flames of a burning cauldron fire, and was gone, clutching her bulging purse.

At Castle Urquhart, heavy oak tables were covered by blood-dripping cuts of finest beef, lying in mouth-watering heaps.

‘Oh, ma wee beauties,’ she said, stroking at the sinews running through the pounds of flesh.