11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

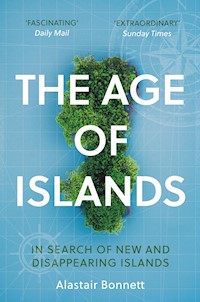

'Extraordinary... A fascinating and intelligent book.' Sunday Times New islands are being built at an unprecedented rate whether for tourism or territorial ambition, while many islands are disappearing or fragmenting because of rising sea levels. It is a strange planetary spectacle, creating an ever-changing map which even Google Earth struggles to keep pace with. In The Age of Islands, explorer and geographer Alastair Bonnett takes the reader on a compelling and thought-provoking tour of the world's newest, most fragile and beautiful islands and reveals what, he argues, is one of the great dramas of our time. From a 'crannog', an ancient artificial island in a Scottish loch, to the militarized artificial islands China is building in the South China Sea; from the disappearing islands that remain the home of native Central Americans to the ritzy new islands of Dubai; from Hong Kong and the Isles of Scilly to islands far away and near: all have urgent stories to tell.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE AGEOFISLANDS

By the same author

Off the Map

Beyond the Map

New Views: The World Mapped Like Never Before

What is Geography?

How to Argue

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Alastair Bonnett, 2020

The moral right of Alastair Bonnett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Except where noted, all photographs and illustrations are by the author.

While every effort has been made to contact copyright-holders of illustrations, the author and publisher would be grateful for information about any illustrations where they have been unable to trace them, and would be glad to make amendments in further editions.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-809-0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-810-6

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-811-3

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-812-0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

Part One: Rising

Why We Build Islands

Flevopolder, The Netherlands

The World, Dubai

Chek Lap Kok, Airport Island, Hong Kong

Fiery Cross Reef, South China Sea

Phoenix Island, China

Ocean Reef, Panama

Natural, Overlooked and Accidental: Other New Islands

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai, Tonga

The Accidental Islands of Pebble Lake, Hungary

Trash Islands

Part Two: Disappearing

Disappearing Islands

The San Blas Islands of Guna Yala, Panama

Tongatapu and Fafa, Tonga

The Isles of Scilly, UK

Part Three: Future

Future Islands

Seasteading

Dogger Bank Power Link Island, North Sea

East Lantau Metropolis, Hong Kong

Not an Ending

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Index

PART ONE

RISING

Why We Build Islands

IN A DARK bar on the shores of Loch Awe a tall, beery fellow leaned into me and slowly explained that the crannogs – the ancient homesteads sprinkled in the lochs of Ireland and Scotland – were the very first artificial islands. I nodded meekly. It seemed likely and he was staring at me with red-eyed certainty. If I’m ever up that way again I may have the courage to lean back and put him right. The truth is that artificial islands are found across the world and that trying to claim any one as ‘the first’ is like trying to locate the first firepit or the first hut. Although often overlooked today, they are just too common to be easily or usefully tracked down to a single original source.

What are they for? Sifting through the layers of island-building history, the main reasons why people built them can be organized as follows: for defence and attack; to create new land for homes and crops; as places of exclusion; as sacred sites; and finally a rag-bag category of islands for lighthouses, sea defence and tourism. If we drill down into each of these purposes, we start to see continuities to our modern age of islands but also differences, not just in terms of number and size but in how they are used. For the majority of the world’s new islands have no pre-modern predecessors. These are the rigs and turbines, dedicated to oil, gas and wind power extraction, that dot so many horizons.

Defence and attack

Many of the reefs of the South China Sea have been bulked out and squared off to house missile silos, naval docks and runways. Although there is a long history of new islands born of strife, the oldest have nothing to do with sabre-rattling. In the Solomon Islands, the Lau fishing people built about eighty islands in a sheltered lagoon by paddling out – year after year, for centuries – and dropping lumps of coral into the water. The Lau built these islands to escape attack from mainland farmers. Many are still inhabited. Their defensive function has ceased to matter but they still offer protection from wild animals and malarial mosquitoes. Elements of this story can also be heard on Lake Titicaca in South America where another fishing community, the Uros, built a similar number of islands many miles from the shore in order to be safe from aggressive neighbours. Unlike the Lau’s solid structures, the islands of the Uros are made of reeds and float. This design reflects the building material to hand but also allowed the islands to be moved if under threat. Reed islands last about thirty years and need to be continuously remade. The Uros maintained these woven structures across hundreds of years. Today they are much closer to the shore and attract tourists from all over the world.

Ancient defensive artificial islands were small, occupied by families not soldiers, and never had much, if any, weaponry. In Europe the construction of more robust and professional artificial island fortresses began in earnest from the seventeenth century, and over the next three hundred years imposing stone forts were built on numerous reefs and sandbanks, usually to guard important ports. Some of the grandest were built by Louis XIV, such as the horseshoe-shaped Fort Louvois. Foundations for Fort Louvois were sunk into a muddy rise in the sea near Rochefort on 19 June 1691. At high tide it still looks startling: a castle rising from the water. In fact, Louvois saw only brief bouts of active military service. The last came on 10 September 1944, when it was shelled and briefly occupied by the fleeing German army.

Like a lot of militarized islets, the history of Fort Louvois is largely one of inactivity. Their main role has been as deterrents: they look big and bold in order to make invaders think twice. Peter the Great, having founded St Petersburg, sought to defend his creation with a series of spectacular sea forts. The first was Fort Kronshlot, built in shallow water during the winter of 1703. The most famous of the Petersburg forts is Fort Alexander, an immense oval begun in 1838. Fort Alexander was big enough to accommodate 1000 soldiers and 103 cannon ports. Like so many other dramatic offshore forts, Fort Alexander quickly became outmoded and, in military terms, useless. Having been demoted to a storage depot, it was given a new lease of life in 1897 when it became home to the research laboratory of the Russian Commission on the Prevention of Plague Disease. For twenty years this isolated, stone citadel caged a variety of animals used in plague experimentation, including sixteen horses whose blood was used to produce plague serum.