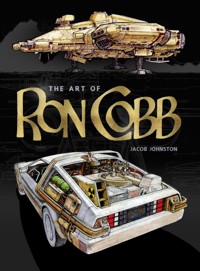

The Art of Ron COBB

Standard edition ISBN: 9781789099584E-book edition ISBN: 9781803360782

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark StreetLondon SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

FIRST EDITION: August 20222 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

© 2022 Estate of Ron Cobb. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at:

[email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for theTitan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any formor by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in anyform of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition beingimposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in China.

Written by Jacob JohnstonProduced by Concept Art Association

CONTENTS

ForeworD

6

Introduction

9

Film & TV

12

Dark Star

14

Star Wars

15

Alien

17

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

38

Dune

39

Raiders of the Lost Ark

40

Conan the Barbarian

44

Night Skies

64

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

66

The Last Starfighter

68

Real Genius

80

Back to the Future

89

Robot Jox

93

Aliens

96

Amazing Stories

102

The Abyss

106

Total Recall

114

Garbo

120

True Lies

122

The Rocketeer

124

The 6th Day

126

Cats and Dogs

131

Firefly

135

Southland Tales

137

Half of the Sky

138

Leviathan

140

My Science Project

140

China Marines

141

The Running Man

142

John Carter of Mars

143

The Day the World Changed

145

Space Truckers

146

District 9

150

Planet Ice

151

Landfall

152

Video Games

154

Cartoons

164

monsters musicand more

174

Album covers

176

Rough Boys

177

Magazine covers

178

Ecology symbol

179

NASA

180

Miscellaneous projects

182

Speculative tech

184

Ron Cobb’s legacy

200

Acknowledgements

206

Afterword

208

ABOVE: Boxing robots. Unused film design, 2003.

FOREWORD

JAMES CAMERON

If you were a fan of fantasy and science fiction films in the 70s and 80s,or are a fan of those films now, you have most certainly seen the workof Ron Cobb brought to life on the screen—probably without realizingit. Ron designed so many of the vehicles, sets, props and costumes of thattime that he is recognized by the generation of designers who came afteras one of the titans of the era. He was certainly a huge influence on me,in my formative years as a fledgling filmmaker, and it was one of my greatpleasures to have been able to work with him, and to realize on screen somany of his designs.

My personal journey with Ron was from fan to collaborator. Longbefore I directed my first movie, I was an avid, maybe even rabid, fan offantasy art. There was no internet search back then—no internet! So,finding and collecting fantasy and science fiction art was done the hardway: I used my allowance (hard-earned mowing the lawn and doingthe dishes) to buy books and magazines at our small town drugstoreand convenience store. For me, it was a creative loop. I’d get my sweatyteenage hands on the latest issue of Eerie magazine with a cover by Frank

Frazetta, or a paperback sci-fi book, with cover art by Berkey or Freas,and I’d be obsessed for the next week or so, drawing and painting myown versions, riffing off their singular styles. This is how I taught myselfto draw and paint in the 60s. And this cycle continued into the 70s,abetted by the publication of whole books of such paintings, whilst themarket for fantasy art exploded.

Two movies thundered onto the science fiction landscape: Star Warsin ’77 and Alien in ’79. The first blew my mind with the possibilities offilm design and set me on the path to becoming a director. I quit my jobas a truck driver and got to work making my own science fiction epic(never made, thankfully). The second starkly demonstrated what theexperience of a movie could be when you really felt like you were there.

In the aftermath of these films, books of their design art were published,and in them I discovered Ron Cobb. It is almost certain that I’d seenRon’s art prior to that, as he was published prolifically in the 70s, butthe first time I really connected a name to his singular images was afterAlien—and that name stuck. At the time, I was furiously designing my own

6

sci-fi movie with the grandiose intention of somehow inspiring somebodysomewhere to fund my epic. And the way I was going to inspire thatconfidence in Mr. Nobody was to draw and paint that epic in advance,in excruciating detail. Ron’s designs inspired me at that critical, seminalmoment in my own creative journey. I pored over his images, and all thewhile careful not to copy them directly, I vowed to apply his principle offinding the exact balance of plausibility and outrageous fantasy.

His designs for the vehicles and spacecraft interiors, spacesuits and propsfor Alien made sense to my eye in a way no other artist’s at that time did.Here was a fantasist that really understood engineering. His designs lookedso possible. Though not an engineer, I had studied physics, was deeply versedin real space technology, and had worked as a mechanic and a precisionmachinist. I knew my tech. And his stuff looked like it would work.

Nobody at that time, or even today, could even remotely predict whata faster-than-light starship of the distant future might look like, but Ron’sproposal—at least for the purposes of a movie—was that its interiorswould be recognizably human spaces, driven by principles of engineeringand ergonomics, and emerging from familiar technology of today. Notthe sleek sterile lines of Star Trek and myriad space designs of the 50s and60s, but a nuts and bolts “lived-in” future, that connected and groundedthe audience. Bulky space chairs with lots of rivets and tubing, that didGod knows what, but looked like they did something important, if notvital to the task of piloting a spaceship. Thanks to Ron we all learnedan important lesson in the 70s… that apparently it’s impossible to fly inspace without having badass space chairs.

Imagine Harry Dean Stanton in his baseball cap and Hawaiian shirtstanding on the bridge of the starship Enterprise. He would be the alien,beamed in from another cinematic universe. But in the corridors andmachinery rooms of the Nostromo, he fit right in. Real people in a realspaceship. Our disbelief was willingly, joyfully, suspended. Both designuniverses, Star Trek and Alien, served a fantasy narrative, but it wasAlien that was the milestone in the creation of a palpable, inhabitable,believable future reality. Ron’s designs made it seem utterly real—touchable. And with a bit of shadowy lighting, and with we the audiencesupplying our sense-memory of dripping water as we watched thecondensers raining with audible plip-plops onto the brim of Harry Dean’scap, we were there. And, it was that, a moment later when the Alien itselfemerged from the darkness, it scared the holy living shit out of an entiregeneration of film-goers.

Some of us still haven’t recovered.

This is the power of design, and this is the genius of what Ron createdto support Ridley Scott’s vision. A few years later, Ridley started work onthe now classic Blade Runner. This film was another seismic influenceon me and the filmmakers coming up around me at the time. Again, afantastic future was made tactile and physically real, in ways we’d neverseen before. It can’t be overstated how important these two films were toeverything that has followed, including my own work.

In 1981, only 2 years after Alien came out, I found myself workingat Roger Corman’s New World pictures, the most influential of theultra-low budget B movie production companies. I started churning outdrawings of spaceships, suits, guns, and creatures, and of course I lookedto Ron Cobb for inspiration. His books, along with those of Hans RuediGiger, designer of the Alien itself, were close at hand on my shelf in theart department.

Bear in mind, that I still hadn’t met Ron at this point. I wasshadowing him. He was mentoring me without even knowing it. Threeyears later, I made my directorial debut on The Terminator. We had nomoney for coffee, let alone design. So, I drew it all myself. Again, Ron’sbooks were always close at hand. I then managed to parlay my successfrom that film into getting hired to direct the sequel to Alien, which Icalled Aliens. Duh. There’s more than one. Get it?

For the first time, I had a healthy design budget. So, of course, myfirst call was to Ron Cobb. And finally, I got to meet the guy who’dbeen such a huge influence all those years. I found him to be one ofthe most delightful human beings I’d ever met. Exploding with ideas,non-stop, taking everything utterly seriously, as if the fate of the freeworld depended on getting the design absolutely correct, and yet doingit all with warmth and humor. Ron always had a twinkle in his eye. Hehad the same healthy lack of respect for human systems and authoritythat I did, born out of the 60s counterculture movement. His iconic andsardonic cartoons were well known to readers of underground comicsand free press, though I only realized that much later.

His humor and cartoon stylings crept into Aliens in the form of thenose-art on the Drop Ship, the Colonial Marines orbital troop carrier—the big boot of the crew’s mascot coming at our face, emblazoned with“Bug Stompers.” A riff on my line in the script, spoken by MichaelBiehn, “It’s a bug hunt.” Which in turn was a reference to StarshipTroopers, the classic novel by Robert A. Heinlein, in which the alien

OPPOSITE PAGE:LurkingCat, purchased by screenwriterand director John Milius.

RIGHT: A sketch for theLoadstar game.

7

adversaries were called “bugs” by his interstellar infantry. And if you lookclosely, under Bug Stompers, is the motto “We endanger species.”

This was the level of detail that Ron thrived on.

My collaboration with Ron was very pragmatic and there was noego. Sometimes Ron would propose something and I’d redraw it. I hadvery specific ideas on the ships and the body armor and the guns, likeVasquez’ smartgun, or the Drop Ship. Then, he’d take my rough designand ‘package it,’ add layers of detail and his own special sauce, and createworking drawings. In other areas, Ron did the whole thing—like in MedLab, the Ops Center, and the corridors. I’d just hand his drawings to myEnglish production designer, Peter Lamont, and say “build it.”

I was so thrilled to be working with him and so excited to see his setdesigns taking shape on the stages at Pinewood Studio in England. PeterLamont really respected Ron’s art, not only because it was brilliant, butbecause it was buildable. His renderings were working drawings. Some ofhis sets he even laid out in plan and elevation drawings—stuff you couldliterally build from. This made Peter’s job a lot easier. The director andthe concept designer were in perfect sync, so the art department werenever in the dark, they just had to figure out how to actually realize someof these ambitious designs on a modest budget. No small feat, and Peterdid it brilliantly. Ron also represented a continuity with the first Alien,which the British team really relied on, when this upstart Canadiandirector and American visual effects team showed up to hijack theirEnglish hit franchise.

Ron was part of a wave that revolutionized film design, especiallyin the sci-fi and fantasy genres. In the past, a production designerwould be hired, and they might bring in a few concept artists underthem, but the production designer was the orchestrator of the film’sentire design. In those days, production designers didn’t specialize in aparticular genre. They might do a suspense thriller, then a drama, andonly occasionally a science fiction film. This led, in my view, to a verystunted growth of sophisticated ideas in science fiction and fantasy film

design, with only very few notable exceptions such as Forbidden Planetand 2001: A Space Odyssey.

George Lucas broke that mold. On Star Wars, he worked directlywith the artists, and chose from among whichever fantasy artists broughtin the best ideas. Ridley Scott took it farther, a couple years later whenworking on Alien. He literally ‘cast’ the design team. H.R. Giger woulddo the alien spacecraft and the creatures themselves, giving theman entirely unique and nightmarish look the world had never seenbefore. And Ron was cast as the counterweight to Giger’s Freudian“biomechanoid” motifs, with his very grounded, very plausible-lookinghuman technical environments. The juxtaposition was electrifying. Itcompletely revolutionized the method of cinema design.

I used the same principle on Aliens, and again two years later on TheAbyss. In the case of the latter film, I cast Ron to design all the humantech of the underwater oil drilling rig, and an up-and-coming designer,Steve Berg, to design the alien NTIs, the Non Terrestrial Intelligences, andtheir technology. Two design aesthetics, from two very different artists,juxtaposed to represent the collision of human culture with an enigmaticalien one. And once again, it worked beautifully.

Ron’s designs for the Benthic Explorer ship, and the deep submergenceoil platform Deepcore, were so real that some people thought we justwent out and shot the movie on “one of those underwater oil rigs,” quiteoblivious to the fact that there is no such thing as an underwater oil rig.I wanted that environment to be deeply grounded in a gritty blue-collarreality, so that the invading alien culture seemed exotic by comparison.

Even Ron’s design for the advanced tech of the experimental fluid-breathing suit looked perfectly plausible, not an overly futuristic look.Many have asked me if a suit like that really existed. To my knowledge,such a suit has never been built, though it certainly could be. Theprinciples are quite sound, and fluid breathing has been demonstratedmany times in animal experiments. Ron and I drew from informationprovided by Johannes Kylstra of Duke University, who was the leadingresearcher in fluid breathing at the time. And if such a suit is ever built,it will look much as Ron designed it.

The Abyss marked the end of my collaboration with Ron, thoughI did call him once frantically to design a Russian MIRV warhead forme on True Lies, which I recall him supplying in about a day. I regret,looking back now, that we never had the opportunity to do it all again,but every film has its own demands. Ron certainly never lacked forinteresting design assignments in the following years.

This book will take you on a journey that will detail the many otheraspects of Ron’s art and his creativity, before and after our work together.My own personal working sojourn with Ron is exemplary of how heworked with other filmmakers, and I’m certain their experience of himwas as joyful as mine was.

Ron was a pioneer of fantasy and science fiction film design, aprolific and visionary artist and a deep and important inspiration to mepersonally. He was a beautiful human being. His body of work is stillimportant today and will stand the test of time. Now that he’s gone, it’sup to new generations of designers to follow his inspiring example, andgo beyond.

LEFT: Alien portrait, Moorwen.

8

INTRODUCTION

Ron Cobb. A name you may have heard in the audio commentary ofa film you grew up loving, or listed in the pages of a ‘making of’book; or maybe it rings no bells at all. His name, immediately recognizedor not, is synonymous with an impactful legacy that spans over fifty years.His life was more like twenty lives—twenty meaningful lives. Let’s behonest, many of us are lucky to experience one or two career pathsduring our lifetime—but not Ron. This was a life filled with iconic film

work, masterful and impactful cartoons, environmental activism, a stintin Vietnam, even an MTV music award, and that’s just the tip of theiceberg. His infectious personality and out-of-the-box, yet still overlypragmatic, design philosophy left a resounding effect, influencing a greatmany people along the way. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves, though—before we explore Cobb’s expansive career, let’s take it back to where itall began…

LEFT: Ron wasa big admirer ofH.P. Lovecraftand this was anod to his work.

9

ABOVE: Galileo’s counterpart, extraterrestrial circa 1680. This was done in the late 1950s as part of an art show.

10

BELOW: Another nod to H.P. Lovecraft: Cthulhu, a fictional cosmic entity.

BELOW: A sketch for the Space Bar video game.

1940, Burbank, California. At three years old, Cobb’s parents movedthere from Los Angeles in the hopes of a better life promised by themid-30s property boom. In ten years, the population spiked from around34,000 to close to 80,000. But middle-class life in budding Burbank wasfar from inspiring to a perpetually daydreaming Cobb. As time went on,he grew more and more discontent with the glib environment aroundhim—until he discovered something that offered an escape: “I began tonotice out of the corner of my eye distant vistas of fantasy, of a world outthere glimpsed through the wonderful window of television and ECComics. I daydreamed and nurtured my fantasies, and to make themmore real, I drew. At the same time, I became introverted, a terriblestudent, and waited for something to happen,” said Cobb in his 1981book, Colorvision.

Through art, Cobb’s nascent imagination took hold, propelled by hisfascination with all things science fiction. “When I was a little kid, I wouldsit out in the back yard,” Cobb said at an IT Networking Party in 2015,“and I swear I could see people signaling me from the moon. And I knew itwas important somehow, but you know, you might say I had a science-fictional childhood, because I always thought about science as adventure,nothing more than adventure, and when it started to appear in moviepictures, I was transfixed. I said, ‘I want to do that somehow.’”

This obsession with the wondrous and impossible continued duringCobb’s high school days. He surrounded himself with like-minded friendsand formed a small club called C.D. Inc—the ‘C’ stood for Cobb and the‘D’ for co-founder Tad Duke. The club’s interests were notably in pranks,atheism, and science fiction, which led to their first club act: seeing War ofthe Worlds in 1953. The creative lot also spent time conceptualizing afictional history of an imagined European country called Donovania.Donovania was home to a prince named Chesley Donovan, aptly namedafter Cobb’s early influencer Chesley Bonestell, a prolific pioneer of spaceart who helped popularize the notion of manned space travel. Eventually,the group renamed themselves the ‘Chesley Donovan Science FantasyFoundation,’ which was, according to Cobb [Colorvision, 1981], “adeliberately pompous and satirical name for a group of introverted andeccentric students. Our mutual fascinations with science, astronomy,philosophy, and theology kept us together until we were in our early

twenties,” he further explained. “Our involvement in C.D. drew each of usout of our introversions, while we nurtured and entertained each other.”

Ron’s wife, Robin Love, also attributes a certain piece of literature toRon’s thirst for the unknown. “There was also a very influentialchildren’s book called Paddle to the Sea. He read it when he was a littlekid—and he came from a family that didn’t really give their kids books.The book is about drifting out and suddenly realizing you’ve gone fromthis little creek into this big, whole world. He would often cite it whendiscussing ideas, that what may seem innocuous or unsurprising at first isin fact the opposite if you allow yourself to drift just a little further.”

In 1955, graduation was looming and Cobb was weighing the optionsof his future. He wasn’t exactly a great student, and with his lack ofinterest in ‘establishment’ education, college (even community college)didn’t spark any type of enthusiasm. It was his skill with a pen that led