Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

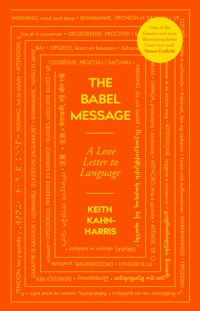

'Quite simply, and quite ridiculously, one of the funniest and most illuminating books I have ever read. I thought I was obsessive, but Keith Kahn-Harris is playing a very different sport. He really has discovered the whole world in an egg.' Simon Garfield A thrilling journey deep into the heart of language, from a rather unexpected starting point. Keith Kahn-Harris is a man obsessed with something seemingly trivial - the warning message found inside Kinder Surprise eggs: WARNING, read and keep: Toy not suitable for children under 3 years. Small parts might be swallowed or inhaled. On a tiny sheet of paper, this message is translated into dozens of languages - the world boiled down to a multilingual essence. Inspired by this, the author asks: what makes 'a language'? With the help of the international community of language geeks, he shows us what the message looks like in Ancient Sumerian, Zulu, Cornish, Klingon - and many more. Along the way he considers why Hungarian writing looks angry, how to make up your own language, and the meaning of the heavy metal umlaut. Overturning the Babel myth, he argues that the messy diversity of language shouldn't be a source of conflict, but of collective wonder. This is a book about hope, a love letter to language. 'This is a wonderful book. A treasure trove of mind-expanding insights into language and humanity encased in a deliciously quirky, quixotic quest. I loved it. Warning: this will keep you reading.' - Ann Morgan, author of Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 387

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Praise for The Babel Message

‘Quite simply, and quite ridiculously, one of the funniest and most illuminating books I have ever read. I thought I was obsessive, but Keith Kahn-Harris is playing a very different sport. He really has discovered the whole world in an egg.’

Simon Garfield, author of Just My Type

‘This is a wonderful book. A treasure trove of mind-expanding insights into language and humanity encased in a deliciously quirky, quixotic quest. I loved it. Warning: this will keep you reading.’

Ann Morgan, author of Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer

‘I would warn everyone to read and keep this beautifully written book … Keith explores the world of language – what it is, what it means and how we use it. Keith’s precisely written prose celebrates the wonderful imprecision of language in all its glory.’

James Ward, founder of The Boring Conference and author of Adventures in Stationery: A Journey Through Your Pencil Case

‘The Babel Message is a gloriously inflected record of an obsession … [It] manages to teach us a great deal about language – its protean energy and its slipperiness – but also makes us properly laugh (a rare Venn diagram, believe me). … Kahn-Harris’s fan-boy passion for the gorgeous surface of written language and his own skill in deploying it make the book a complete delight.’

John Mitchinson, author of The QI Book of General Ignorance

‘In this unlikely story of a quixotic translation, Keith Kahn-Harris illuminates how language-learning can hone our minds, strengthen our empathy, and lead us all to justice. Read this book – and immerse yourself in the raw pleasure of linguistic diversity.’

Daniel Bögre Udell, Executive Director, Wikitongues

To fully appreciate the many writing systems featured in The Babel Message, I recommend viewing this ebook in at least 14 point font size.

v

THE BABEL MESSAGE

A Love Letter to Language

KEITH KAHN- HARRIS

xi

To my father, Paul Harris, who has taught me absolutely nothing about language but absolutely everything about pursuing one’s interests, come what may.

Contents

WARNING, read and keep

In the Babel myth, God thwarts the builders of the Tower by creating a ‘confusion of tongues’. In this book I will exult in this confusion. I will show you what a short message written by an Italian confectionery manufacturer looks like when translated into dozens of languages, most of which I cannot speak and many of which are in scripts I cannot even read.

And there may very well be mistakes.

The final chapter of my previous book began with a Hebrew epigraph.1 Even though I speak and read the language, at some point in the preparation of the proofs the letters were reversed by the non-Hebrew-speaking typesetter. It’s an easy mistake to make; Hebrew is written from right to left and including such a script in an English manuscript is asking for trouble. It was up to me to spot it though, and I didn’t.

While I am going to do my darnedest to ensure that no language is presented back-to-front, I cannot guarantee that somewhere along the line, a letter will be dropped, an accent will be missed, or something else will go horribly wrong in my attempts to wrangle these unruly beasts in order to present them to you, the reader, for your delectation.

No one knows all of language. Even aspects of one’s own tongue can be confusing. We make do with what we have. In this book I have set out to celebrate the diversity of language using the tools I have available. Those tools included my training and experience as a sociologist, an uneven grounding in linguistics and a reasonable, but not fluent, knowledge of several languages. That’s more than most, less than some. But reproducing the many languages in this book correctly would xivbe a challenge for even the most impressive polyglot or the most experienced professional linguist.

Acceptance of the risk of mistakes is a precondition for using any language. It’s certainly essential for anyone who aspires to revel in the diversity of languages. And it was also necessary for Ferrero, the company that produces the multilingual warning messages discussed in this book.

If language weren’t risky, if we were not always in danger of being misinterpreted, where would be its pleasures and its value? The alternative – a single logical language, perfectly understood by everyone equally – would lead to a tyranny of dullness. As I will argue towards the end of this book, Babel may be confusing and chaotic, but it’s also invigorating and exciting. What’s more, if we can learn to enjoy the languages we do not understand, and take pleasure in the risks of mis-understanding, we might even be able to get along with each other better.

Some readers who speak a language presented in the book might contest the wording of a particular translation. If so, that’s fine – translation cannot be an exact science – and I encourage readers to send me alternative translations via my website. Corrections of my mistakes are welcome. I am always up for correcting myself in public.

If wrangling languages is a challenge, wrangling human beings is even harder. Happily, in researching and writing this book, it has often been a pleasure. I still can’t believe that I have managed to turn such a quixotic project into a book. So thanks to my agent Antony Topping for making the impossible possible and to Duncan Heath and the team at Icon for taking such a leap of faith. My wife and children have shown extreme fortitude in coping with this latest meander in what xvhas always been an idiosyncratic career. I will always treasure the conversations we have had around the dinner table about this project.

Thanks to the friends and contacts on social media who enjoyed the translations with me when I posted them and who ‘got’ the project from the outset. For years I’ve been writing about how social media brings out the worst in us. Sometimes though, it can be a place of joy and laughter. I am grateful to everyone who has reminded me of that.

Thanks to Yaron Matras, Nick Gendler and Deborah Kahn-Harris, who read drafts of the book, making many useful suggestions and pointing out some of the more embarrassing errors. The errors that they did not spot are my responsibility alone.

Most of all, my heartfelt thanks to the dozens of people and organisations who provided me with translations, connected me with other translators or gave me advice and suggestions. I am still stunned that so many people answered my pleas. In fact, I have received so many translations that I could not include all of them in this book (a constantly updated list can be found via my website). I’ve credited individual translations that appear in the book to their authors in the endnotes and, in addition, here is the full, glorious list:

Glenn Abastillas, Kamila Akhmedjanova, Rashad Ali, Nicholas Al-Jeloo, Merjen Arazova, Carmen Arlando, Glexi Arxokuna, Costas Avramidis, Gavin Bailey, Jenny Bailie, John Baird, Xavier Barker, Jesmar Luke T. Bautista, Brian Bourque, Clive Boutle, Daniel Boyarin, Shamma Boyarin, Jackson Bradley, Ross Bradshaw, Jeffrey Brown, Dale Buttigieg, Malcolm Callus, Vivienne Capelouto, Felisa Castro Bitos, Andrea Cavaglia, Sally Caves, Kate Clark, Culture Vannin, xviAlinda Damsma, Khulgana Daz, Kelvin Dobson, Jenny De Guzman, Henri de Nassau, Tebôd de Rogna, Stephen DeGrace, Michel DeGraff, Maricar Dela Cruz, Meryam Dermati, Luke Doran, Bruno Estigarribia, Clive Forrester, Adam Frost, Louise Gathercole, Mark Geller, Richard Goldstein, Guernsey Language Commission, Ida Hadjivaynis, Tony Hak, Jan Havliš, Christoph Helbig, Aliaksandr Herasimenka, George Hewitt, Hnolt, Achim Grundgeiger, Thorsten Hindrichs, Elliot Hoey, James Hopkins, Dauvit Horsbroch, Colin Ireson, Sulev Iva, Marta Jenkala, Jasmin Johnson, Daniel Jonas, Lily Kahn, Kobi Kahn-Harris, Gabriel Kanter-Webber, Thomas Kim, L’Office du Jèrriais, Jorge Lambia, Teresa Labourdette, Loïc Landais, Joseph Langseth, Damian Le Bas, Tsheten Lhamo, ‘Liberal Elite’, Lia Rumatscha, London Euskera Irakaslea, Fernando López-Menchero, Kelly MacFarlane, Rahima Mahmut, Norah Makhubela, William Manley, Josephine Sitoy Maranga, Alena Marková, Jan Marquis, Yaron Matras, Puey McCleary, Richard E. McDorman, Yoseph Mengitsu, Gorka Mercero Altzugarai, Shido Morozof, Peter Miller, Krikor Moskofian, Carola Mostert, Naja Motzfeldt, Pierrick Moureaux, Anupama Mundollikkalam, Jo-Ann Myers, Nir Nadav, Julian Nyča, Liam Ó Cuinneagáin, Ofis Piblik ar Brezhoneg, Veturliði Óskarsson, Claude Passet, Megan Paul, John Payne, David Peterson, Siva Pillai, Sally Pond, Krishna Pradhan, Guy Puzey, John Quijada, Gary-Taylor Raebal, Hadzibulic Ridburg, Elvire Roberts, Wrenna Robson, Gerald Roche, Simon Roper, Richie Ruchpaul, Tom Ruddle, Arawi Ruiz, ‘Dr St Ridley Santos’, Stella Sai Chun, Mark Sanchez, Erich Schmidt, James Seymour, Neil Shaw-Smith, Owen Shiers, Jonas Sibony, Param Singh, Dave Snell, Christine Stewart, Sebastian Suh, Jeremy Swist, Tamil Studies UK, Christian Thalmann, James Thomas, Fiorenzo Toso, Anna xviiTreschel, Riitta Valijärvi, Oana Uta, Simon Varwell, Zareth Angela Vergara, Danelle Vermuelen, Lars Sigurdsson Vikør, Lina Vdovîi, Craig Volker, Imke von Helden, Shaul Wachsstock, Anne Waldek-Thill, Jeremy Wallach, Yair Wallach, Neil Walley, Jackson Walter, James Ward, Michael Wegier, Rebekka Weinstein, Patrick Wilcox, Joseph Windsor, Lidia Wojtczak, Abigail Wood, Kylie Wright, Ghil’ad Zuckermann.

289

Notes

1. Kahn-Harris, Keith. Strange Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and the Limits of Diversity. Repeater, 2019.

Introduction

A surprising obsession

Eggs are joyous things.

The egg represents life itself, the possibility of something wonderful emerging from within a hard yet brittle shell. The egg is celebration and hope. The contents are a source of mystery and wonder. Who can resist the lure of discovering what the egg contains?

Like the real eggs they resemble, there is something so right about Kinder Surprise Eggs. The outer foil is a riot of orange and white, festooned with multicoloured, bouncy letters. Unwrap it and you find the smooth, warm colour of its chocolate shell; slightly sticky yet delicately firm. The underside of the shell recalls white albumen and within it the yolk – a bright yellow capsule – tempts you with its secrets. Break it open and there is a further puzzle: what will the toy look like once assembled?

I hate to resort to the cliched term ‘iconic’ to describe Kinder Surprise Eggs, but they are certainly instantly familiar, loved by many (not just children) and drawing on the deepest levels of human symbolism. No wonder that every month, the number of Kinder Surprise Eggs sold worldwide would be enough to cover the surface of Tiananmen Square in Beijing.1 And as with other classic brands – Heinz Tomato Ketchup for example – most of its competitors are fated to be seen as second-rate.xx

Iconic products such as Kinder Surprise Eggs are often taken for granted. They are just there, nestling on the shelves of a supermarket or (as in my local corner shop) on the counter next to the cash register. I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know that Kinder Surprise Eggs existed. When my children were younger, the Eggs were a handy go-to treat to keep them busy or distracted. I knew what they were and what to expect of them; they were reliable. I didn’t pay much attention to them.

Yet at some point I found something within a Kinder Surprise Egg that forced me to sit up and pay attention; to stop taking them for granted and look at them with fresh eyes. One day, as I was assembling the toy for my son, I glanced at the small sheet of paper included within the capsule. I had seen it before, maybe I had even read it, but on this occasion I actually saw it. It drew me in, sparking an obsession that has lasted for years, long after my children entered adolescence and were no longer interested in the product.

The flimsy document found in Kinder Surprise Eggs – only 12cm by 5cm, covered on both sides with tiny text – has become, for me, a kind of treasure map. It has led me on an adventure that is still unfolding.

Why not join me on the journey? To do so, all you need to do is to buy a Kinder Surprise Egg. Before you eat the chocolate and have fun with the toy, take a close look at the slip of paper that remains.

What you are now holding in your hands will vary, depending on which country you bought the egg in (about which, more later). But in Europe, as well as in large swathes of Asia and the Middle East, this is what it will look like on the front and back:xxi

Confused yet? You should be. Crammed into 120cm2 is a riot of blood red and jet black scripts, gnomic texts, strange diacritics and mysterious symbols. Scan your eye over the text more closely and you are likely to find a few words that look familiar. For me, and for most readers of this book, the most familiar is marked with an ‘EN’ for English and announces, with a Lilliputian gravity:

WARNING, read and keep: Toy not suitable for children under 3 years. Small parts might be swallowed or inhaled.

xxiiIt’s a reasonable thing to warn of. The toys are indeed minuscule. I’m not sure how many other readers actually keep the sheet, but I haven’t just kept it, I have collected multiple versions of this text that has become for me a source of beguiling, and sometimes baffling, mysteries.

On loving the languages I do not understand

As an eight-year-old waiting my turn in my trampoline class, I used to read the translated warning messages printed on the crash pads. I don’t even remember what the message warned of. I do remember though that one of the languages was German and contained the word Rahmenpolster. I’d mouth the word again and again: Rahmenpolster, Rahmenpolster, Rahmenpolster. It barely mattered what the word actually meant (I only recently discovered that it refers to a soft protective coating over a metal frame).

A few years later, on a family holiday in Greece, I taught myself to read the language, revelling in spelling out street signs while never learning a single useful spoken phrase. As I grew, it became a matter of fierce pride to me that I could tell the difference between written Japanese and Chinese, that I could spot Turkish at twenty paces, that I knew ‘æ’ and ‘ø’ can never be found in Swedish.

The sounds of foreign tongues also called to me. Perhaps I was rebelling against my parents’ post-war suspicion of Germany, when I came to find the precise, compounded diction of that language attractive. I learned to distinguish the rising tones of Cantonese, heard in my local Chinese restaurant, from the less tonally varied cadences of Mandarin. The pronounced gutturals of Arabic offered me a full-blooded distinction to xxiiithe more familiar, and less throaty, Hebrew sounds I heard in synagogue. One of my proudest moments was when, on a trip to Australia a few years ago, I managed to work out that a broadcast on public radio was in Estonian, rather than the similar-sounding Finnish (the key was that it mentioned the Estonian newspaper Postimees).

Of course, I have also learned to read, speak and write languages other than English. I loved reading the work of Gabriel García Márquez in my A-Level Spanish class and took a perverse pleasure in the ludicrously formal signoffs I was taught in my French for Business AS-Level. I learned enough spoken Mandarin to have a basic conversation on my travels in China when I was nineteen. At the age of 30 I built on my basic modern Hebrew to get to a level where I could follow and contribute to academic seminars. I’m currently working through lessons in Finnish – a fiendishly complex tongue whose sounds I adore – on the Duolingo app.

Yet I have never achieved fluency in anything other than English. I don’t need to – and that’s the curse of the native English-speaker. While my life has been enriched by the learning of foreign languages, if I hadn’t, my everyday life would not have been negatively impacted. I have the luxury of being able to decide that, since I can’t keep up all my languages, I keep up none of them, allowing my knowledge to slowly erode. I don’t face the lingering fear of being cut off from the world that a monoglot speaker of, say, Lithuanian might face. Nor do I live somewhere where casual bi- or trilingualism is the norm, as in parts of Africa, India and Asia.

However much I might love the English language – its bizarre Germanic-Romance hybridity, its ridiculous spelling, xxivits innumerable syntactical oddities – there is a shaming blandness to being a native English-speaker. The easy facility with which a group of Danes or Dutch effortlessly switch to English if even one speaker joins them, always causes me embarrassment. I envy those speakers of minority British languages such as Welsh or Gaelic who form the last redoubt against the linguistic levelling of these islands. The bog-standard English that I speak with a faint London accent may strike locals as enchanting when I travel in the American Midwest, but it lacks the dialectal distinctiveness of Geordie or the luxuriant burr of West Country English.

Kinder Egg linguistics

For me, the languages I find in translated messages on everyday products offer a tantalising glimpse of the linguistic pleasures available outside the English-speaking world. Before I encountered the Kinder Egg message, the most diversity I ever found was on the list of local distributors found on boxes of Kleenex tissues. But they had nothing on Kinder Eggs – indeed, Kleenex conflate Danish, Norwegian and Swedish into one language, using a ‘/’ to offer individual alternatives to particular words. I had never seen Georgian, Azerbaijani or Latvian on product packaging until I discovered Kinder Eggs.

Packed into one tiny slip of paper are 37 different languages, in eight different scripts. These are, in order of appearance:xxv

[Side one]

Armenian (1)

Azerbaijani

Bulgarian

Czech

Danish

German

Greek

English

Spanish

Estonian

Finnish

French

Croatian

Hungarian

Armenian (2)

Italian

Georgian

Kyrgyz

[Side two]

Lithuanian

Latvian

Macedonian

Dutch

Norwegian

Polish

Portuguese

Romanian

Russian

Slovak

Slovene

Albanian

Serbian

Swedish

Turkish

Ukrainian

Persian

Arabic

Chinese (Traditional characters)

Chinese (Simplified characters)

Take a closer look at it and you will find inconsistencies and mysteries aplenty:

Which is the original version of the message? Given that Ferrero, the company that produces the Eggs, is based in Italy, is Italian the mother of all the translations?What do the two-letter codes before each message refer to?xxviWhy do some messages mention under-3s (including the English one) whereas others appear not to?There seem to be two Armenian texts, one including the message and the other including some kind of address. The warning message is written all in capital letters in Armenian script and marked with the code ‘HY’. The address text is written in lower case and marked with the code ‘AR’. Why? Why? Why?Some languages print the word ‘WARNING’ in capitals and others do not. In Danish and Norwegian it is Adversel and in Swedish VARNING. Do some languages prohibit the use of all-caps words?Stare hard enough at the warning message sheet, and it dissolves into anarchy, chaos and brain-melting puzzles. And there’s more: some toys come with extra messages specific to them. The mini slingshot I found in one Egg, for example, includes a multilingual warning not to aim at the eyes or face.

Something odd also happens the more you delve into the world of Kinder Egg linguistics: you start to realise what isn’t there. How many other versions exist? Where are they used? Who decides on their content? Why is it that the sheet of paper used in Europe includes all EU official languages except for two (Irish and Maltese)? Who decided not to include them? And given that millions speak ‘minority’ European languages like Catalan, there is a strong case for including them too. In fact, there are 5,000–6,000 languages spoken in the world today, together with innumerable dialects. The Kinder Egg message can only be translated into a fraction of them. When looked at in this way, the message sheet starts to look oddly impoverished. Why should a multilingual Dane need a specific xxviimessage in Danish while a monolingual speaker of one of the indigenous languages of Greenland (an autonomous Danish territory) not be provided with a translation into his or her own language?

This message, so brutally short, legalistic and commanding, also contains hidden ambiguities:

‘WARNING, read and keep’: Who is being warned? Why do we need to keep the message? Where should we keep it?‘Toy not suitable for children under 3 years’: How is suitability to be understood here?‘Small parts might be swallowed or inhaled’: By whom and under what conditions?The ‘obviousness’ of the message depends on all kinds of cultural and linguistic assumptions. Look closer and these assumptions evaporate into nothingness, leaving only a disembodied voice, addressing someone somewhere about something for some reason.

I don’t blame the manufacturers for this confusion and I don’t see it as a bad thing. In fact, I revel in this glorious muddle. For it is nothing but a manifestation of the ways in which language seduces and bamboozles. The creators of the Kinder Egg warning message were trying to communicate something simple to us, but they ended up creating a sheet of paper of byzantine complexity.

Language is never simple and so communication is never simple. Despite that, using language to try to communicate is also just what humans do. We are driven to connect with each other. And it was the need to connect that drove me to write this book …xxviii

Reaching out

Kinder Eggs and I have a history. I first came out to the public as a warning message-lover at a talk I gave at the 2017 Boring Conference in London. In preparation for the talk, I commissioned translations of the warning message into more languages. I started with Irish and Maltese, in order to complete the set of EU languages. After that I found it hard to stop: I collected Luxembourgish, Cornish, Welsh and then Biblical Hebrew. At the end of the talk I led the audience in a joke pledge to never buy another Kinder Egg until they included a translation of the warning message into Cornish.

In 2018 I recorded a podcast for the BBC Boring Talks series and added yet more languages to the collection. I also included an appeal for listeners to send me warning message sheets from around the world, and listeners in South Africa, Brunei and Nepal duly obliged.

Every so often, following the release of the podcast, I’d receive an email offering me a translation into a new language. I received one such email in late March 2020, in the first phase of the Covid-19 pandemic. The sender inquired whether I would be interested in a recording of the warning message into Shanghainese (it could only be a recording as the language is rarely written down). In the end, the offer didn’t pan out, but it still flicked some kind of switch in my brain. In a time of disconnection, commissioning translations would bring me connection, yet the translations themselves would be unreadable to me. Could there be a better metaphor for the human yearning to reach out to others and the limits of doing so?

Another thought seized me: for some years I had been writing and researching about the worst aspects of humanity. I had published two books that went to very dark places, xxixexploring racism, antisemitism, Holocaust denial and other forms of denialism. I had argued that we needed to come to terms with the fact that human diversity isn’t always something to celebrate, since human beings hold to a wide range of incompatible moralities and desires. I still believe this, but in 2020 I had a strong yearning to demonstrate the other side of the coin, that human diversity can be a wonderful thing. To write about linguistic diversity during challenging times reminded me that language is the most amazing thing that human beings have created.

So spring and summer 2020 saw me firing off email after email: to language promotion officers in the Channel Islands, to professors of Sumerian, to Romani rights activists, to creators of invented languages, and to almost everyone I could think of in my address book who spoke a language that wasn’t to be found on the original warning message slip. Some never replied, a few frostily refused, but the majority agreed and many more went further: sending me the translations by return, recommending experts in other languages, offering me reams of explanations as to word choice. I posted the results of my searches on my blog and on social media. As my collection grew, so people would write to me explaining how much they enjoyed the project and encouraging me to keep going.

However much translating the Kinder Egg warning message into multiple tongues might seem a pointless project to some, other people just get it. Reading languages you do not understand is an underrated pleasure. I’m not the only person to find the experience of seeing a familiar message rendered unfamiliar an enchanting one. And my joy in incomprehension is all the greater when the translation appears in a script I’ve xxxnever previously encountered, features unusual diacritics, or just looks plain weird.

Becoming a language fan

I’m a language fan. To be one you don’t need to be trained in linguistics, nor do you have to be multilingual (after all, you can be a tone-deaf fan of Mozart). All language fandom requires is that you find it thrilling that there are more tongues in the world than one person could ever speak. You have to enjoy the experience of not being able to understand speech and writing. And above all, you have to view language as humanity’s most magnificent creation.

This book will try to convince you to become a language fan too (if you aren’t one already). I also have a serious agenda: my experience of reaching out to linguists and speakers of a vast array of languages across the world has taught me that the myth of Babel needs to be turned on its head: the splintering of human language into multiple tongues is not a metaphor for the fall of man into conflict and division. Rather, it is a metaphor for a different kind of unity. A world that speaks in one language could only be united in oppressive ways, forcing us to speak so plainly that all creativity and nuance is lost. In contrast, a world that speaks in many languages is one in which human individuality and invention can flourish. There is unity here too; unity in incomprehension. When I encounter a language I don’t understand I am reminded of the amazing tendency of human beings to forge new paths, to do things in different ways.

In the modern world this unifying Babel is under threat. Around half the world’s languages are classified as seriously endangered and some estimates suggest that by the end of xxxithe century, 90% of our languages will have lost their last living native speaker. Globalisation, the mass media, migration to big cities and the centralised modern nation state have all contributed to this erosion. Linguistic diversity is linked to biodiversity, as the same forces threaten both. Just as we need to treasure and protect the ecological diversity of the natural world, so should we guard the diversity of the human world. Translations of the warning message into endangered or lesser-known languages remind us that these languages live, they exist and should not be erased.

One of the ways we can learn to appreciate linguistic diversity is by challenging some of the myths we hold about language. Language is never an exact expression of our thoughts and intentions, languages are never entirely coherent things, translation is never an exact science. Rather, to speak is to engage in a creative act, drawing on systems of signs that can never be fixed. We are always improvising, contributing to the never-ending process of linguistic evolution. Part of the beauty of language is that it can never simply be a ‘tool’ of communication; it is always just out of reach. Any attempt to raise one language up over another, to see a language as a fixed, defined thing, will always end up in someone, somewhere getting silenced.

The same is true for the categories we create using language. If we delude ourselves that categories like ‘nations’ are natural phenomena to which we simply apply names, then we pave the way for attempts to use them to exclude people, to treat some people as ‘naturally’ belonging to them and to treat others as unnatural outsiders. Fortunately, language has an impish habit of subverting our attempts to do so. However much we try to pin the butterfly, to hammer down the world xxxiiinto neat divisions, something always resists our control: the unruly ability of language to burst human boundaries.

Revealing the ambiguities in the warning message, the messy process through which it has been translated and the challenges in communicating it, also makes a powerful statement: we refuse to silence the glorious babble of humanity, we refuse to treat any language, any nation, any state, as deserving of a louder voice, a bigger platform.

This, then, is a book about Kinder Surprise Eggs and it is not about Kinder Surprise Eggs at all. It is an investigation into the apparently trivial mysteries contained in a mundane slip of paper hidden inside a chocolate egg. When read correctly, the message sheet communicates another message beyond ensuring you don’t inadvertently harm small children.

It is not just a message, it is the Message, and that is how I will refer to it from now on.

Just as we break open the chocolate egg to reveal the treat inside, so I will break apart the apparent mundanity of the Message to reveal the wonderful, messy and bewildering reality of what language is. This is the kind of treat that can be enjoyed by human beings of any age.

Notes

1. Padovani, Gigi. Nutella World: 50 Years of Innovation. Rizzoli International Publications, Incorporated, 2015: 192.

Part 1

Set the controls for the heart of the Message

Chapter 1

The Message

On the liminality of Kinder Surprise Eggs

How human it is to create something so complex!

Kinder Surprise Eggs are certainly complex things. Regular eggs have an inedible shell within which edible life gestates. The Kinder Surprise Egg has an inedible outer foil wrapped around an edible chocolate shell, containing a yolk-coloured but inedible capsule, that itself encloses further inedible objects. The Egg is what anthropologists would call a liminal object; one that straddles the boundary between edible and inedible.

Research suggests that children do have the ability to understand the ‘double nature’ of the Eggs.1 However, in some countries, most notably the United States, the liminal nature of an object like this is intolerable. In the US, after long legal battles, the Food and Drug Administration decreed in the 1990s that confectionery cannot contain inedible objects.2

The approach taken in other parts of the world, including within Europe, is to alert responsible adults to liminality. By legally mandating that warnings be included on and within the Egg, the adult purchaser will understand that special care should be taken to manage the dangers of an object that is both one thing and another thing.

Language – specifically written language – must bear a massive weight of responsibility here. Product warnings are strange things. Warnings contradict the temptations of 4products designed to be irresistibly tempting. They may tell the consumer not to use something they have actually bought (like cigarettes). Warnings can also be expressions of a kind of fear from the manufacturer. In the US, the annual ‘Wacky Warning Label Contest’ is both funny – one example is a fishing lure marked ‘Warning, harmful if swallowed’ – and draws attention to the over-litigious nature of American society that leads manufacturers to try to anticipate any conceivable misuse of their product.3

Warnings are expressions of an impersonal form of care. The anthropologist Margaret Mead is supposed to have said that the first sign of civilization in ancient culture was a broken femur that had healed, because this shows that someone stayed to help the victim recover. Whether or not she actually said this or it is historically accurate – and there is some doubt about both4 – is a moot point; what’s important here is that the capacity to care goes way back and way deep. To help someone recover from a broken femur, in ancient times or today, requires a degree of intimacy, even if it is just a doctor or nurse putting the leg into a splint. In contrast, written warning messages are distanced from the body. We don’t know the people who wrote them, and they do not know who will read them. If we fail to heed warning messages, their authors will not have the ability to care for us.

There is a whole body of academic literature on the construction of warning messages, that draws on psychology, law and graphic design.5 Ferrero appear to have adhered to best practice in constructing the Message: it conforms to various international and national legal regulations (some of which will be discussed later in the book). It includes both visual and written elements in the warning. It clearly identifies the nature 5of the hazard and the consequences for not avoiding it. The font is similar or identical to Helvetica; one that is frequently used on official signs and messages and is noted for its clarity and simplicity.

The biggest challenge to the Message’s efficacy is something that the manufacturers can do very little about: will the Message be read? After all, it is a competitor in a crowded market for attention.

Paying attention

When you first heard about this book, you might have found its premise amusing. A whole book on the warning messages in Kinder Surprise Eggs! The reason this seems funny is that the Message is usually among the many things in our lives that we relegate to the background. Other warnings might intrude into our life in ways that grab our attention, such as error messages – both visual and aural – on our computers or flashing accident lights on the motorway. The Kinder Surprise Egg cannot intervene in our lives in such a visceral fashion. It is one of the many objects in our lives that are festooned with text and that we do not pay too much attention to. Indeed, we cannot pay attention to them, since to do so would consume most of our lives. How would we ever cook dinner if we assiduously read the information on every component of the ingredients? One of the reasons why Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder is such a serious condition is that the sufferer is constantly paying too much close attention to the minutiae of everyday life.

The writer Georges Perec, in an essay first published in 1973, suggested that we needed to focus our attention on the ordinary, urging the reader to, among other things, ‘question 6your teaspoons’.6 Such attention can be a source of pleasure and a form of politics. As Perec argued:

In our haste to measure the historic, significant and revelatory, let’s not leave aside the essential, the truly intolerable, the truly inadmissible. What is scandalous isn’t the pit explosion, it’s working in coalmines.7

I am not going to claim that paying attention to the Message could change the world. However, the Message could help us reflect on the impossibility of bearing the burdens of responsibility that modern life places upon us. To buy a Kinder Surprise Egg for a small child is just one of those occasions when information is piled on us and, should we fail to read it closely or at all, it is we who will bear the consequences.

But let’s, for the moment, assume that most adults who buy Kinder Surprise Eggs were assiduous readers of the Message; that they seek out the version in their language and study it carefully, even keeping the Message indefinitely as they are told to do.

There would still be a problem.

That problem’s name is language. And it is beyond the ability of even the most experienced writer of warning messages to solve.

The slipperiness of language

To speak or to write is not a simple process in which a coherent message from our brain is transferred to someone else’s brain. That we are all meaning-making creatures doesn’t imply that we share an identical understanding of the system through which we make meaning. The capacity for language knits 7us humans together, but that doesn’t mean anyone ‘owns’ a language in its entirety. Nor are our individual and collective assumptions completely known to us.

The connection of language to the world beyond us is slippery and often tenuous. It has never been particularly controversial to note that the association of words to things is arbitrary (outside of onomatopoeia); the word ‘toy’ is not a property of toys themselves. In the early twentieth century, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure went further than this, arguing that words – known as ‘signs’ – do not refer to things themselves, they refer to the mental concept of the things themselves. The sign is a combination of the ‘signifier’ (a sound) and the ‘signified’ (a concept).

Saussure’s work was a major contributor to a wider trend in twentieth-century humanities and the social sciences, known as the ‘linguistic turn’. The nature of language and how it shapes our world became the preoccupation for a host of disciplines. One of the fundamental questions is whether we can exist outside language in the first place: is there a world outside the sign? The intellectual currents known as postmodernism and post-structuralism, and their advocates such as Jacques Derrida and Jean Baudrillard, are often accused of treating the world as a purely linguistic construct with no intrinsic meaning. Certainly, their determination to reveal the arbitrariness of the connection between signifier and signified seems to treat meaning itself as equally arbitrary.

But you don’t have to be a dyed-in-the-wool postmodernist to recognise that meaning is an exceptionally slippery thing. We cannot get inside one another’s heads and know for sure that our own signifieds are the same as other people’s signifieds. All of us have known the anxiety of not being sure that 8the other understands what we are trying to say in the way we want to be understood. The fact that, through language, human beings can cooperate and get things done in the world is a kind of miracle.

The social sciences have revealed the messy process through which language works on an everyday basis. Detailed analysis of mundane language use shows, for example, how political talk involves a constant process of knitting together contradictory ‘interpretive repertoires’.8 Look in detail at conversation and you find an astonishing ability to turn fragments of talk into a meaningful dialogue. When I was doing postgraduate work, a fellow student analysed a conversation between a ‘psychic’ and her client. Pretty much everything the psychic said turned out to be incorrect, but she and her client ‘worked’ to turn the encounter into something that was revelatory. Conversation analysts have shown how our talk involves all kinds of implicit assumptions that we share without realising it. Harvey Sacks, a pioneer of this methodology, focused on the beginning of a story by a young girl – ‘The baby cried. The mommy picked it up’ – in order to reveal the implicit ‘rules’ through which we find it ‘obvious’ that the baby is the mother’s baby.9

The Message is suffused with assumptions: that the warning is addressed to the reader; that ‘read and keep’ refers to the Message itself; that ‘toy not suitable’ refers to the toy inside the egg; that ‘small parts’ refers to the small parts of the toy. The confidence of Ferrero that the Message is intelligible shows how far we rely on rules that were never explained to any of us. While we might be able to assume that the reader understands some aspects of the Message, there is much else that seems to rest on less solid ground. For example, there is the 9presumption of the unknown writers of the Message that they can and should be obeyed. Then there is the assumption that pointing out the danger of the toy to under-3-year-olds necessarily implies that the adult reader will not accept this risk. Indeed, the explicit mention of 3 years as the cut-off point for suitability implies a process of child development where all children progress at the same rate.

Reading and writing the Message

Since we are constantly misunderstanding each other in talk, we rely on processes of ‘repair’ that put conversation back on track when mutual understanding breaks down. The Message is not a contribution to a conversation. It cannot be clarified. The differences between the assumptions of the writer and reader cannot be made explicit.

The literary theorist Roland Barthes distinguished between ‘readerly’ and ‘writerly’ texts.10 In the former, readers passively consume texts suffused with common-sense meanings. In the latter, the text is open for the reader to ‘write’ the text, to produce new meanings. No doubt Barthes would have seen the Message as eminently readerly. We cannot be so sure. The Message may be being rewritten all the time.

On top of this unstable meaning-making, Ferrero also have multiple languages to contend with. At one level, the challenge is the same with the Message in every language. No natural language can ‘solve’ the problem of language’s fundamental instability (although some ‘constructed’ languages have tried, as we shall see later in this book). But the nature of the challenge can be different in different languages. And the challenge is compounded by the challenge of translation itself. 10

Translation is a work of recreation, an act of writing, a strange alchemical process whose task, according to Walter Benjamin, is ‘to release in [the translator’s] own language that pure language which is under the spell of another, to liberate the language imprisoned in a work in his re-creation of that work’.11 That may sound a little overblown when it comes to a technical translation of a short message, but the fundamental task of translation is daunting whatever you are translating. As the translator David Bellos has written:

[T]he practice of translation rests on two presuppositions. The first is that we are all different – we speak different tongues and see the world in ways that are deeply influenced by the particular features of the tongue that we speak. The second is that we are all the same – that we can share the same broad and narrow kinds of feelings, information, understandings, and so forth. Without both of these suppositions, translation could not exist. Nor could anything we would like to call social life. Translation is another name for the human condition.12

Even if we speak the same language we all have to face the dual nature of the human condition. Indeed, George Steiner argued that translation is something that we do within languages as well; speakers of the same language cannot assume perfect understanding of each other, they have to work at understanding the other.13 Ferrero’s challenge is all the greater for having to confront the human condition on a tiny piece of paper, in multiple languages – and with human lives at stake. 11

The scale of the challenge makes me even more obsessed with the Message. It also helps me view Ferrero, a multinational corporation, with indulgence; to see it as irreducibly human. They are trying, against almost impossible odds, to tell purchasers of products they themselves made, who are scattered across the world, to take care and avoid harming their children. The only tool they have available is a monologue forged out of multiple written languages. That tool is imperfect and out of their control. And they are simultaneously trying to communicate in the same packaging a radically different message: that this product will entice and delight small children.

This book revels in the resulting contradictory, confusing, slippery result. The warning Message sheet is a tiny monument to the heroic attempts and desperate failures inherent in humanity’s reliance on language. It is an attempt to control that which cannot be controlled. Its limitations are all our limitations.

So I hereby name the piece of paper on which the Message is inscribed the Manuscript. It is an ancient tome, on which the story of language itself can be read.

Notes

1. Benelli, B., C. Donati, N. Consonni, and B. Morra. ‘Food Products Containing Inedibles: Children Recognition of Their “Double Nature” and Manipulation-Play Behaviour’. International Congress Series, Advances in Pediatric ORL. Proceedings of the 8th International Congress of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 1254 (1 November 2003): 497–500.

2. Eldred, John S., and Stuart M. Pape. ‘Toys and Confectionery – A Legally Hazardous Combination?’ Food and Drug Law Journal 53, No. 1 (1998): 1–8.

3. Michigan Lawsuit Abuse Watch. ‘Wacky Warning Label Contest’. Accessed 10 January 2021. https://www.lawsuitfairness.org/wacky-warning-label-contest

4. Hackner, Stacy. ‘That Margaret Mead Quote’. Stacy Hackner, 21 April 2020. https://stacyhackner.wordpress.com/2020/04/21/that-margaret-mead-quote/

5. Robinson, Patricia A. Writing and Designing Manuals and Warnings, Fifth Edition. CRC Press, 2019; Wogalter, Michael S. Handbook of Warnings