Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

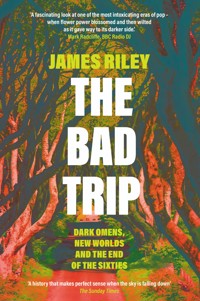

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'A history that makes perfect sense when the sky is falling down.' - The Sunday Times Beneath the psychedelic utopianism of the sixties lay a dark seam of apocalyptic thinking that seemed to rupture into violence and despair by 1969. Literary and cultural historian James Riley descends into this underworld and traces the historical and conspiratorial threads connecting art, film, poetry, politics, murder and revolt. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones, the Manson Family and Roman Polanski, ley-line hunters and Illuminati believers, Aldous Huxley, Joan Didion and the Beat poets, radical protest movements and occult groups all come together in Riley's gripping narrative. Steeped in the hopes, dreams and anxieties of the late 1960s and early '70s, The Bad Trip tells the strange stories of some of the period's most compelling figures as they approached the end of an era and imagined new worlds ahead.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 627

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

About the Author

JAMES RILEY is Fellow of English Literature at Girton College, University of Cambridge where he works on modern and contemporary literature, popular film and 1960s culture. Widely published, he has written for The i, Fortean Times, Vertigo, Monolith and One+One. He has contributed chapters to books on the fiction of the 1960s, ghosts, psychedelia, and contemporary protest. James has lectured internationally and has performed spoken word shows in London, Vienna and Coney Island, New York. He likes coffee, makes films and is the author of the blog Residual Noise.

Prologue: Apotheosis

In early September 1969, a small group of people arrived at an airfield in Hampshire close to the south-east coast of England. The weather was warm, but a thick bank of cloud had muffled the sun, creating a cold zone in the middle of the runway. As the group discussed their plans a large helium balloon inflated alongside them. It was not unusual to see weather balloons drifting across the sky in this part of the world, but the team that convened that day were not meteorologists. The group consisted of a musician, an artist, a cinematographer and a sound engineer, and their interest in balloons was not so much scientific as creative: they had turned up at the airfield to shoot a film.

The musician – tall with shoulder length hair, an obsessive stare and professorial glasses – was John Lennon of the Beatles. The artist – small with shoulder length hair, an obsessive stare and an aura of formidable intelligence – was Yoko Ono, avant-gardist of international repute.1

Lennon and Ono had recently married. They had met at an exhibition of Ono’s work at London’s Indica Gallery in mid-1966. They stayed in touch, gradually feeding each other’s fascination until, in May 1968, they began a musical collaboration. Released as Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins (1968) the album consisted of tape-loops, whistles and shrieks; it was a shock to most listeners matched only by the record’s cover: Lennon and Ono naked, staring blankly at the camera. Two Virgins clearly, strategically and intentionally, told a different story to that of Please Please Me (1963). This was not a record made by four cheeky lads from Liverpool; this was a record made by two artists unafraid to challenge expectations of what ‘music’ should sound like and what musicians should look like.

Standing on the airfield as the balloon started to rise, Lennon would have been well placed to reflect on the differences between the albums, the stories they told and the versions of himself they represented. Indeed, since the recording of Two Virgins he had completely rebooted his life. He had left Cynthia and Julian, his wife and young son, to be with Ono; he had embarked on a new musical direction with the Plastic Ono Band, and he had left the Beatles, his musical partners of the last ten years. Their last public concert had been in January 1969, a jam-session on the roof of the Apple building in London’s Savile Row. Forty minutes of noodling through ‘Get Back’ (1969) ended with the police turning up to complain about the volume.

Ono meanwhile had been catapulted from the relative obscurity of the contemporary art scene into the celebrity aura of her new husband. Along the way she experienced all the sexism and racism that came from being a Japanese-American woman in the public eye in the late 1960s, to say nothing of the ire she generated as the ‘cause’ of the Beatles’ break-up.

Although the Beatles would publicly dissolve in April 1970 with McCartney’s departure, it was at the start of September 1969, mere days before the airfield rendezvous, that Lennon had privately announced his intention to leave. Life in the band had become increasingly frustrating. The sessions for what would turn out to be their final two albums, The Beatles, aka the ‘White Album’ (1968) and Let It Be (1970), had been fractious and divisive. It felt like the four members – Lennon, McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr – had been pulling in different creative directions.

There were other reasons, of course. Money, legal issues, the decision to stop touring, the mutual burnout that comes from spending more than a decade living with four other people. Lennon was also coming down following the Beatles’ trip to India in 1968. Transcendental Meditation under the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was not all that it had been cracked up to be and Lennon was left in a spiritual void. A void of enormous wealth and rock star privilege, but a void nonetheless. He was looking for something and someone to fill it. Shortly after their marriage, Lennon and Ono bought Tittenhurst Park, a mansion near Ascot in Berkshire. Away from London, the gaze of the media and the dying days of the Beatles, Lennon and Ono drifted further into their private world as intertwined artists. As Lennon would put it in a 1971 letter, they were now JOHNANDYOKO.2

Their day in Hampshire was part of this metamorphosis. They were there to make what became the short film Apotheosis (1970). The idea was simple: a camera attached to the balloon would record the flight until the film ran out. Lennon and Ono wanted a single shot that would show them gradually disappearing as the balloon flew higher.

The word ‘apotheosis’ means the process of ascent into the figure of a god: it’s an acceptance of the divine. Some of Lennon’s more conservative critics may have expected such arrogance from the man who, in 1966, had said the Beatles were ‘bigger than Jesus’, but in terms of Lennon and Ono’s relationship, the film has a more personal message. Apotheosis depicts a movement beyond, a stark visual statement of rising above everything. Here are Lennon and Ono, stood at the crossroads of their personal and artistic lives, offering a clear sign that a new story is about to begin.

For all its simplicity though, if Apotheosis is about an escape or ‘a release from earthly life’, then it’s a release that’s never fully granted. The balloon ascends and goes elsewhere, Lennon and Ono do not. They remain on the ground, static and shrinking as the camera rises. Rather than a way of waving goodbye to the world and its concerns, the film speaks of the desire to depart: an act of incredible longing that’s left unfulfilled.3

All of which begs the question, why was this desire so strong? Yes, they had personal problems and were embroiled in business matters, the likes of which they would continue to encounter in their life together. But apart from such tensions, what might Lennon and Ono have wanted to fly away from? Had the world become so terrible by September 1969 that they would want to leave it all behind? Why would anyone else, for that matter, want to try to escape from the sixties?

Notes

1. My account of the making of Apotheosis was informed by Peter Doggett’s The Art and Music of John Lennon (London: Omnibus Press, 2009), 230–32.

2. For details of the last days of the Beatles and the relationship between Lennon and Ono see: Ray Coleman, Lennon: The Definitive Biography (New York: Harper Perennial, 1999), 419–88. For a general overview of the Beatles, their work and their career, see Philip Norman, Shout!The Beatles in their Generation (USA: Fireside, 1996). For more detailed accounts events such as the rooftop concert, see Tony Barrell, The Beatleson the Roof (London: Omnibus, 2017).

3. Definition of ‘apotheosis’ from the Oxford English Dictionary 2nd edition, volume 1. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), p. 559.

PART I

Demons Descending

CHAPTER I

The Devil’s Business

On 9 August 1969, the actress Sharon Tate hosted a small party at 10050 Cielo Drive, the Los Angeles home she shared with her film director husband, Roman Polanski. With Polanski working in London, Tate, who was eight and a half months pregnant, had gathered her friends and house guests for the weekend. Present on the night were the celebrity hairdresser Jay Sebring who was Tate’s long-term confidant and former boyfriend, Abigail Folger, heiress to the Folger Coffee Company, and her partner, the actor Wojciech Frykowski. Tate had met Polanski in 1966 and it was while working with him on The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967) that they became close. They had married in London in January 1968, just as Polanski was completing his second American feature: the Satanic horror movie Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Based on Ira Levin’s 1967 novel of the same name and featuring Mia Farrow as the young New Yorker Rosemary Woodhouse, the film charts her nightmarish pregnancy in the shadow of an occult conspiracy emanating from the city’s sinister Bramford Building. For the newly-wed Polanskis, life could not have been more different. The expected arrival of their baby was a source of great joy and, far away from the noise of New York, 10050 Cielo Drive had become Tate’s ‘love house’. Since moving in in February 1969, much effort had gone into preparing the nursery.

Cielo Drive is an affluent residential area on the west side of Los Angeles. A classic retreat for the wealthier members of the city’s entertainment industry, the drive has always been verdant, quiet and isolated. It’s also close enough to Beverly Hills to enjoy the area’s bustling social life. On the evening of the ninth, Tate and her friends had dined at El Coyote, a Mexican restaurant on Beverly Boulevard. Returning to the house, they spent the rest of night talking before retiring to bed. Everyone in the party would have drifted to sleep with every reason to feel safe in that house. In 1969 the villa at 10050 had the security that came with money and influence. It occupied a gated, three-acre site the entrance to which was at the peak of the drive, nestled into a cul-de-sac. Perfect for all the relaxed, celebrity gatherings the Polanskis had hosted since moving in. The perfect place, it seemed to Tate, to raise a child. Perfect, precisely because it was not the kind of place that you might wander by of an afternoon: you would only be there if you had a reason to be there. Which is why the night-time appearance of a carload of black-clad young people carrying ropes, knives, wire cutters and a gun should have caused concern. It should have, but it didn’t. The privacy of Benedict Canyon was also its downside. People mind their own business in the LA hills.

It was shortly after midnight when Frykowski woke to the sound of movement in his room. He found a tall man looming over him. This was Charles ‘Tex’ Watson and he had arrived at the party with his friends: Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Linda Kasabian. They were members of the Family, a commune-cum-cult held together by the con man, criminal and sometime musician, Charles Manson. ‘Who are you?’, asked Frykowski, confused and disorientated. ‘I’m the devil,’ replied Watson. ‘I’m here to do the devil’s business. Give me all your money.’1

Towards the climax of Rosemary’s Baby there’s a scene in which Rosemary – exhausted from an apparent miscarriage and months of psychological distress – begins to hear a baby crying through her bedroom wall. She realises it is coming from the neighbouring apartment, the home of Minnie and Roman Castevet, the weird old couple who had been supportive at the start of her pregnancy but whose behaviour in the latter, traumatic, days had become sinister and threatening. Rosemary follows the noise and finds a strange partition in the hallway closet: a door that joins the two apartments. Brandishing a knife Rosemary creeps through and comes upon a dark gathering. Her husband Guy, the Castevets and the rest of the coven that populate the Bramford attend the presence of a baby: her baby. To Rosemary’s horror it is put to her that the baby was born safely but Guy is not the father. The child has a more ominous parentage: he is the son of Satan, the devil born on Earth. It’s a terrifying reveal but there’s something about that partition door that carries a greater, more intimate horror and which goes some way to describing the horror that Frykowski must have felt when he encountered Watson. All the terrible things that have happened to Rosemary in the film have happened because of that door, because her private space has not been private. Finding the door confirms all of Rosemary’s worst fears: your house is not your own, your body is not your own, your child is not your own. The devil has dominion everywhere.

Unfortunately for Frykowski and the rest of Tate’s party, ‘the devil’s business’ was not merely an act of theft. Watson, Atkins and Krenwinkel heeded Manson’s order to ‘destroy the house and everyone in it’. They had already killed Steven Parent, a young man who had come to see William Garretson, the caretaker at Cielo Drive. Garretson had spent the summer living in a cottage on the property: tending the garden, looking after the dogs, smoking weed. Parent had hung out with Garretson that evening, and when he left after midnight he ran right into Watson. They faced each other on the driveway for a few seconds before Watson raised the gun he was holding and shot Parent four times. Garretson apparently heard none of this, nor did he hear the gunfire, screams and sounds of struggle that later came from the main house. Manson-lore has him listening to ‘The End’ (1967) by the Doors late into the night.2

Frykowski, Folger, Sebring and Tate were lined up in the living room. Frykowski had been bound in nylon rope. Watson told them all to get down on their stomachs. He was still asking for money at this point. Sebring made a lunge for him, received a gunshot to his side and was later beaten and stabbed to death. Meanwhile Tate, Folger and Frykowski were trussed with a rope that had been thrown over the ceiling beam, as if they were about to be hung. Frykowski struggled free and attacked Atkins before running for the front lawn to shout for help. He was stabbed and shot multiple times by both Atkins and Watson. Folger also got free and made for the back-porch door that led to the swimming pool but was killed by Krenwinkel. Multiple stab wounds. That left Tate who had witnessed the deaths of her three friends. She was stabbed sixteen times by Atkins, Watson and Krenwinkel. Watson then tied a joint noose around the necks of Tate and Sebring’s bodies while Atkins used some of Tate’s blood to smear ‘PIG’ on the wall.

The carnage at Cielo Drive was matched only by the deaths of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca the following night, 10 August. Manson decided to personally lead the death squad of Watson, Krenwinkel, and fellow Family member Leslie Van Houten. ‘Doing’ the Tate house had been far too disorganised, he thought. This time the proceedings would have some discipline. After setting out from their base of operations, the dilapidated Spahn Ranch on the Santa Susana Pass Road, they prowled the streets of central Los Angeles for an hour or two. Following Manson’s lead Watson drove to the wealthy district of Los Feliz, close to Griffith Park, finally alighting outside 3301 Waverly Drive, the LaBianca residence.

Dispensing with the inconvenience of unreliable firearms, Manson entered the house armed with a cutlass, as if leading a pirate raiding party. Sitting in his lounge, enjoying a beer in the early hours of Sunday morning, Leno looked up from his newspaper and found Manson – short, bearded and intense – looking at him, sword by his side. Leno looked at Manson, Manson stared back at Leno. Rosemary pottered in the bedroom. Another diabolical encounter, but this time there was no introduction, just a curt instruction from Manson: ‘Be calm, sit down and be quiet.’ Leno watched, in shock, as Manson went to the bedroom and retrieved Rosemary. She struggled and protested as Manson tied them together with long leather cords. ‘Everything will be okay. You won’t be hurt,’ he said to them both as he took Rosemary’s purse and walked back out the front door. A short time later, Watson and the others entered the house. They greeted the couple and quickly made it clear that this was not just a robbery.

The LaBiancas were separated, Leno remained in the front room, Rosemary was taken back to the bedroom. Using a carving knife taken from the kitchen, Watson killed Leno with multiple wounds to his chest and body. Rosemary, face down on the bedroom floor was killed next, stabbed by Krenwinkel and Van Houten. Leno’s corpse was then mutilated. Watson cut a large ‘X’ into his chest before adding ‘WAR’. Krenwinkel went at both bodies with a fork and then shoved it into Leno’s abdomen. Emblazoned, and with the fork still sticking out, Leno was hooded with a pillow case. Just as they had done with Tate, the murderers then began to write in the blood of their victims, scrawling ‘DEATH TO PIGS’, ‘RISE’ and, most enduringly, ‘HEALTER SKELTER’ (sic) around the living room and the kitchen.3

Savagery. It is difficult to describe the Tate–LaBianca killings in any other terms. They speak of the violent loss of loved ones and murder at its most senseless. That said, as unpalatable as it seems, there was a certain kind of logic informing the deaths, albeit an extremely twisted logic. The motive had little to do with theft, despite the small amounts taken from each scene. Manson knew the house at Cielo Drive and had something of a grudge against its former resident, the music producer Terry Melcher, but killing Tate and her friends had little to do with revenge.4 Instead, as was revealed during his protracted trial of 1970–71, the key was in the writing left behind. ‘HEALTER SKELTER’ was a reference to ‘Helter Skelter’, a Lennon and McCartney song from the ‘White Album’ which Manson had heard shortly after its release in November 1968.

‘Helter Skelter’ along with Lennon’s ‘Happiness is a Warm Gun’ and George Harrison’s ‘Piggies’ became touchstones for Manson and the Family. As he listened to the songs on a daily basis, Manson got a clear message of imminent societal breakdown. ‘Look out’, says ‘Helter Skelter’, things are ‘coming down fast’. Life’s ‘getting worse’, says ‘Piggies’, because the ‘bigger piggies’ in their ‘starched white shirts’ are ‘Stirring up the dirt’. They need ‘a damn good whacking’, the realisation of which would lead to the empowerment, satisfaction and ‘happiness’ of the ‘warm gun’. The aggression of these songs would have made it easy for someone like Manson to ‘receive’ an invitation to violence, and he came to believe that the Beatles were using their music to communicate with him directly. That said, Manson was neither a survivalist-in-waiting nor an earnest class warrior seeking a validation of his politics. Instead, the event he called and prepared for as ‘Helter Skelter’ was one part of a weirdly messianic personal narrative which far exceeded the themes and ideas dealt with on the ‘White Album’.5

Whether he really believed this pitch or not, the outline, as prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi discovered during Manson’s trial proceedings, went as follows. The modus operandi of the Family was to incite an apocalyptic race war between black and white America. They would do this by committing atrocious acts of murder in the homes of affluent white people, leaving suggestive evidence that the perpetrators were black. In the ensuing street battles and general chaos as decades of racial tension and mutual distrust came to the fore, the Manson Family would retreat to the desert of Death Valley in a convoy of high-powered dune buggies and descend into a secret subterranean world. There, in the imagined company of the Beatles themselves, the Family would sit out the destructive black revolution. They would remain hidden until the members of newly sovereign black nation inevitably faltered in their unfamiliar role as leaders. At which point Manson, his multiplied disciples and the Beatles would re-emerge from ‘the bottomless pit’ and assume their rightful place as rulers of the new dawn. This was ‘Helter Skelter’: the moment when the world as we, the squares and the straights, knew it would end and all that remained would come down to Manson as his rightful inheritance.6

The writer and journalist Joan Didion was living in Los Angeles at the time of the Tate–LaBianca murders. Her house on Franklin Avenue, in a once-opulent part of Hollywood, was large and roomy. She lived there with her husband and daughter; she played music there; held parties there and often hosted Sunday lunches that ran on into Monday. Rock bands lived across the street, Janis Joplin would drop by, and during the long weekend gatherings there was much talk of auras, zen and philosophy. The perfect sixties household: a space of togetherness, communality and free thinking. But for Didion this was to be a fleeting vision of the sixties. As the summer of 1969 came around things began to change. ‘Everything had been so loose’, recalled fellow writer Eve Babitz to journalist Barney Hoskyns, ‘now it could never be loose again’. Where ‘a guy with long hair’ had been a ‘brother’ in 1967, by late 1969 ‘you just didn’t know’.7 On first reading, Didion’s account of this period, her long essay ‘The White Album’ (1968–78), makes it clear that, whatever the apocalyptic ideas of Manson himself, the Tate–LaBianca murders marked out another ‘end’, one that was just as catastrophic but more specific. The work of the Manson Family, it seems, announced not the end of the world per se, but the end of a particular way of thinking and acting. The end of an era.8

The Family may have looked like hippies and talked like hippies, but unlike the peaceful flower children they were less interested in the expansion of consciousness than the pursuit of a collective death trip. Put into practice at Cielo Drive, this project had a seismic impact on the cultural landscape in the months that followed. Up and down the Sunset Strip, once-bustling clubs lost their clientele, and across the canyons the doors to previously open houses slammed shut. And it wasn’t just a sense of fear that descended. The emergence of Manson and his followers seemed to ignite an attitudinal shift within the youth culture of Los Angeles and beyond. As Lennon remarked to Rolling Stone shortly after the murders became public, the Family exemplified a new generation of ‘aggressive hippies’, the ‘uptight maniacs wearing peace symbols’ who increasingly turned up at his door with bizarre interpretations of his lyrics.9

Such talk of ‘aggressive hippies’ in the national press would have likely brought to mind the wild-eyed picture of Manson that appeared on the cover of Life magazine on 19 December 1969. Staring out from underneath the headline ‘The Love and Terror Cult’, like Rosemary’s Satanic baby catapulted into adulthood, Manson was used to introduce America’s reading public to ‘the dark edge of hippie life’. Two years earlier, Time magazine had dispatched Robert Jones to report on the hippie scene, an assignment that resulted in the cover story: ‘Hippie: The Philosophy of a Subculture’. In outlining what he took to be a consistent, coherent worldview, Jones spoke of ‘young and generally thoughtful Americans’ who were hoping ‘to generate an entirely new society, one rich in spiritual grace that will revive the old virtues of agape and reverence.’ Now here was Manson held up by Life as a dark glass to that new society. As a terrifying distortion of the popular images associated with the much-vaunted ‘Summer of Love’ and a figure who simultaneously confirmed the establishment view that nothing good could come from this new culture of the young, Manson thus came to signify the devil’s business done; the traumatic cancellation of the hippie project; the dashing of the decade’s utopian hopes: the end of the sixties.10

Charles Manson, formerly Charles Milles Maddox, arrived in San Francisco in March 1967. He was 32 years old and fresh out of prison. Manson had spent most of his life up until that point behind bars. His longest and most recent stretch – a ten-year sentence of which he served the best part of seven – was for violating an earlier set of parole terms and for trafficking women across state lines. Locked up from 1961 in Washington and then California the thief, hustler, con man and now pimp came under the sway of the usual prison influences. He learnt how to survive within the general population of gangsters and murderers, while also quietly learning from them: how to coerce, how to intimidate, how to control. Manson also threw himself into a period of self-improvement, taking courses on Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936), participating in group therapy and reading up on psychiatry.

Prisons are petri dishes just as much as they are containers, and the varied methods used to deal with the problems of society often find their test beds among the incarcerated. The psychic landscape of post-war America was a heady mixture of individual effort and individual scrutiny – Benjamin Franklin meets Sigmund Freud – and in its attempt to cultivate the penitent, the prison system drew heavily on the techniques of this psychotherapeutic climate, aiming first for punishment and then for reprogramming. That Manson was taking to the library, rather than engaging in the violence that had marked his earlier stints in jail, seemed a validation of this rehabilitative American Dream. However, his interest in the psychology of self-improvement was professional just as much as it was personal. It helped with his depression and taught him to cope as a prisoner, but Manson was also fascinated by the insights it provided into the techniques of persuasion and suggestion, the various ways a personality could be broken down and rebuilt, and how a therapist could establish a subtle but dominant authority over an individual or an entire group. Having navigated the physical dangers of the prison yard, Manson turned to the inner world of the mind. He was, in other words, learning how to coerce, how to intimidate and how to control.

According to his biographer Simon Wells, Manson encountered three other points of influence while an inmate at McNeil Island prison, a trio of texts, ideas and images that would resonate with him for years to come. He read Robert Heinlein’s science fiction novel Stranger in a Strange Land (1961); he learnt about L. Ron Hubbard and Scientology from his cellmate Lanier Ramer; and, in February 1964, he saw the Beatles perform on The Ed Sullivan Show.11

An eclectic range of influences but not without points of overlap. Stranger tells the story of Valentine Michael Smith, a human born during a manned spaceflight to Mars. Raised as a Martian, Smith returns to Earth possessing extreme wealth, strange abilities and childlike innocence. Over the course of Heinlein’s parable, Smith establishes the Church of All Worlds, a commune-style congregation that combines human religion, esoteric beliefs and aspects of Martian life. Smith is eventually killed as a heretic by members of a rival religious group, but his sexually charged, very wealthy followers continue the work of his church, setting forth at the close of the novel to transform human culture.

In 1950 Hubbard, a friend and sometime correspondent of Heinlein’s, had published Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, a book that located the cause of psychological and physical ailments to the retention of ‘engrams’: traces of painful or traumatic memories stored in the unconscious or ‘reactive’ mind. Dianetics stated that through the application of an analytic technique called ‘auditing’, engrams could be erased from the mind – like recordings from magnetic tape – thus enabling the subject to become a ‘clear’, free of burdensome neuroses and fully able to pursue a life of high achievement. By 1954 Hubbard had developed his self-help system into the Church of Scientology, a religious organisation that promoted the spiritual significance of mental and physical health and used the principles of Dianetics as its central ‘technology’.

Opinion differs as to whether Heinlein had Hubbard in mind when he wrote about Smith and the Church of All Worlds, but if you did harbour messianic fantasies, you could do worse than to transform your work of pop psychology into a fully fledged religion. Scientology promised much to its flock, clear minds and new beginnings; but within its deeply hierarchical structure, it also promised much to its auditors, the ability to clear minds and to offer new beginnings. As Ed Sanders said of Manson’s enthusiasm for the discipline, his interpretation of its practices was of great use ‘when he began to re-organise the minds of his young followers’.12

And the Beatles? How do they fit into this? Watching the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964 along with 73 million other viewers, Manson was presented with a curious spectacle. Here were four young men who had appeared from nowhere and yet seemed able to bring American culture to its knees. They could stop traffic, bring the nation to a halt and reduce crowds of teenagers to a screaming mass. If Heinlein and Hubbard offered the fictional and practical techniques necessary for the cultivation of a messianic mindset, for Manson the fame of the Beatles was the goal. Manson believed he could achieve their level of power and influence with the careful application of these tools.13

Manson initially gravitated towards San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district out of necessity. With cheap housing and a range of free community services, the microclimate that revolved around the intersection of Haight and Ashbury Street was the ideal location for a parolee to find his feet. At the turn of the century, Haight-Ashbury had been a prosperous, middle-class area well served by the city’s cable-car network. However, by mid-century the combined effect of the Great Depression and the threat of a proposed freeway project had reduced the area to a virtual ghost town. With residents moving out to the suburbs, the grand Victorian properties were turned into flats and boarding houses. At the same time rents were rising in North Beach, the city’s beatnik enclave. The abandoned, dilapidated Haight thus became the go-to area for those wanting to live on the fringes.14

Economic shifts influence the fabric of every city, but what made the mid-sixties resettlement of Haight-Ashbury notable was the speed and extent to which its residents generated a vibrant culture. Shops, rock bands and various forms of social enterprise proliferated, with groups like the Diggers working to maintain the area’s infrastructure. From 1966 the Haight also had its own newspaper, the San Francisco Oracle edited by Allen Cohen. As Danny Goldberg has recently outlined, these various interests did not always co-exist in harmony. The Diggers, led by Emmett Grogan and Peter Cohon, took their name from the 17th-century English radicals who cultivated common ground in defiance of laws regarding land rights. The Diggers of Haight-Ashbury similarly advocated a mode of communality in which everything could and should be free. They were into redistribution and recycling: taking the unwanted food from San Francisco’s markets and cooking it up into a daily stew they distributed to the community. They also gathered up and gave away clothing in spaces they operated as ‘free shops’. Such altruism was a boon to the large number of travellers, drifters and runaways who converged on the area as it – and its fame – grew. However, for the entrepreneurs and small businesses who attempted to cater to the same crowd, the Diggers’ social agenda caused problems. Grogan saw any kind of commercialism as anathema to what his group were trying to achieve, and he was not afraid of letting shopkeepers and promoters know, even if they were bringing in vital revenue to local artists and producers. For the Diggers, the spectre of capital had no place in the Haight; instead they encouraged a gift economy, a collective of mutual support and a much more nebulous but no less pervasive currency of ‘love’.15

These ideological differences aside, those who lived within and contributed to the ecology of the Haight saw it as a city within a city, one that attempted to exist away from the social obligations and financial expectations that governed post-war America. To this ‘outside’ world Haight-Ashbury was, by 1966, a zone of autonomous existence that exemplified the type of activity that has come to be known as the ‘counterculture’.

Writing in ‘Youth and the Great Refusal’, a March 1968 article for The Nation, the American sociologist Theodore Roszak described the counterculture as:

the effort to discover new types of community, new family patterns, new sexual mores, new kinds of livelihood, new aesthetic forms, new personal identities on the far side of power politics, the bourgeois home, and the Protestant work ethic.16

At least from an American perspective, the hippie was the stereotypical example of this ‘effort’. In his report for Time Robert Jones described ‘the cult of hippiedom’ as those who:

are unable to reconcile themselves to the stated values and implicit contradictions of contemporary Western society and have become internal émigrés seeking individual liberation through means as various as drug use, total withdrawal from the economy and the quest for individual identity.17

Roszak and Jones were both suggesting that at some point in the early to mid 1960s, a portion of America’s ‘youthquake’ – its under-25 age group – morphed into a sector recognisably different from so-called ‘mainstream’ society. This was a separation made possible by the relative security that greeted the baby boomers as they came of age. Rather than claim the material benefits of this post-war affluence – the stereotypical suburban house, new car and solid white-collar job – this demographic eschewed such rewards in favour of communal experimentation. Alternative living patterns and alternative ways of thinking; minds opened not just by drug use but also through exposure to Eastern literature and a revival of interest in mysticism.

Jones and Roszak were not alone in their attempts to map this new post-war field. The word ‘hippie’ had emerged from a miasma of tabloid reporting between 1963 and 1967 which had in turn drawn upon jazz slang of the 1930s and 40s. ‘Hippie’ was taken from ‘hipster’ and ‘hepcat’, words for someone ‘in the know’, but which latterly became all-purpose labels to describe drug users, social misfits and ‘beatniks’ (yet another media term, from the late 1950s). This ‘reportage’ went hand in hand with works of popular sociology like Harrison E. Salisbury’s The Shook-up Generation (1958) that applied a language of deviancy to visible trends in postwar youth culture. This generic grouping pulled together a wide range of activities under easily identifiable umbrella terms. As a diminutive ‘hippie’ is an extremely reductive term, while words like ‘subculture’ describe something ‘lower’ than, and by implication inferior to, ‘mainstream’ society.18

In contrast, Roszak’s preference for ‘counterculture’, particularly in the title of his 1969 book, The Making of a Counterculture, makes a very different claim. Looking over the events of the decade Roszak did not recognise a ‘phase’ of youthful rebellion but rather the strategic adoption of an alternative lifestyle. A lifestyle that was not just existing in parallel with but was at odds to the culture – the taste, the manners, the artistic and intellectual values, the maintained conventions – of the dominant sociopolitical landscape. To back up this claim, Roszak argued that the activities he described were not isolated examples, but markers of a widespread change of mood. Between 1965 and 1969, parallel behaviour could be seen on an international scale, in London, Liverpool, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin and Tokyo: all urban centres with high concentrations of educated, creative and, crucially, disaffected young people. As Joseph Berke put it in his book Counterculture (1969), what lay behind the stoned stereotypes was a wave of youth-led, politically-orientated attempts to move away from ‘the parental stem’. This was meant literally in terms of the nuclear family and metaphorically in terms of the governmental, economic and psychological structures of ‘Western’ (i.e. white middle-class) society.19

In January 1967 Golden Gate Park, the green and pleasant space that the Haight fed into, played host to ‘a gathering of the tribes’, the Human Be-In. Spearheaded by Cohen and the Oracle’s art director Michael Bowen, the Be-In was part festival and part rally that attempted to unify the varied groups that made up San Francisco’s complex subculture. Diggers, anti-war protesters, members of the Berkeley Barb and free speech activists were convinced by the ‘heads’ of the Haight to join in the public demonstration of a shared community ethos. The event involved speeches, blessings, group chanting and performances by a host of San Francisco bands including the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. Overall though, the crowd (which peaked at around 30,000) was the event.

It was at the Be-In that Timothy Leary, ex-Harvard academic turned LSD proselytiser encouraged the crowd to ‘turn-on, tune-in and drop-out’. Although this invitation to a kind of radical solipsism jarred with the far-left rhetoric on display elsewhere during the day, it was perfectly in sync with the mantras and peace invocations of poets Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder who opened the event. Stalwarts of the 1950s Beat scene, in the intervening years Ginsberg and Snyder had undergone a deep immersion in Hindu and Buddhist religious practices. Resplendent with beards, prayer beads and ritual conch shells, they looked like holy men, and by bookending the event with such sacred sentiments, they symbolised what has become the enduring image of the Be-In and the culture it reflected. This un-anchored ‘new society’ of the young was embarking on a spiritualised separation from mainstream society.20

While the ‘crusades’ of evangelist Billy Graham rumbled on and the American Bible Society’s Good News for Modern Man (1966) became the text of choice for the Christian Church, the proceedings of the Be-In indicated that the counterculture was developing a kind of ground zero religion. This melange of Eastern spirituality, ‘alternative’ living and consciousness expansion would soon reside under the indistinct umbrella of ‘New Age’, but for the collective counterculture that took the Haight as its base, these ideas were crucial to its growing mythology and public status as a burgeoning social movement.

The astrologer Gavin Arthur laid much of the philosophical groundwork for the Be-In via his regular column for the Oracle. He had also been consulted during its planning and had determined 14 January as the most astrologically congenial date for a harmonious mass gathering. Aged 66 in 1967, Arthur was something of an elder statesman among the San Francisco counterculture: a mystical teacher with an eventful life behind him that had involved gold prospecting, commune leadership and, as detailed in his book The Circle of Sex (1962), esoteric sexology. Drawing on various sources including the theosophist Madame Blavatsky, he came to see the 1960s as marking a great and long-lasting change in the direction of human culture. This optimistic tribe of the young bringing forth messages of peace and happiness held up a way of life that rejected the violence and warfare that had dominated the lives of previous generations. As Gary Lachman explains, Arthur looked forward to a coming era of ‘brotherhood’ and ‘universality’, dubbing the 1960s ‘The Age of Aquarius’.

Behind this popular image lies a long history of stargazing and prediction, a tradition of speculation that relates to nothing less than change of cosmic significance. ‘Astronomically’, as Lachman continues, the Age of Aquarius is ‘the effect of a wobble in the Earth’s rotation, part of a curious phenomenon known as the “precession of the equinoxes”’. Roughly every 2,000 years, ‘the constellation against which the sun rises […] at dawn on the vernal equinox changes’. In the 20th century it rose against Pisces, having shifted from Aries just prior to the birth of Christ. The next constellation would be Aquarius, which should occur sometime around the year 2000, ‘give or take a century or two’. Arthur could not have made a grander claim about the 1960s. To be entering the Age of Aquarius meant to be embarking on ‘a massive change in consciousness, a return, in short, to the Golden Age’.21

The ‘Golden Age’ refers to a mythical, prelapsarian state of unity between men and gods. It is described in Works and Days, an essay on agricultural life written around 700 BC by the Greek poet Hesiod. Hesiod imagines a rural idyll ‘remote from toil and misery’ in which golden fields of grain yield harvest after harvest. There’s no strife in the Golden Age. Everyone is free to spend their time feasting and enjoying the world’s abundance. However, it doesn’t last. Hesiod goes onto describe a long period of decline across four successive ages of human culture, each one further lacking the lustre and luxury of the first: the Silver Age, the Bronze Age, the Heroic Age and the Iron Age. The last, the Iron Age, is the most recent and corresponds to Hesiod’s own time in the late 8th and early 7th centuries BC. He describes a climate of toil, conflict and distress. According to Hesiod the Iron Age is one of enmity in which brothers turn on each other and violence prevails. Scholarly opinion differs as to whether he was describing a period of actual crisis or if he was offering cautionary instruction on the responsibilities of the farmer. Either way, in Works and Days, the Golden Age stands as a shining symbol of society at its best. It’s an image of a wonderful, lost world, but Hesiod suggests its joys can be revived if we humans choose to live in harmony with the land, the gods and each other.

In the Oracle, Gavin Arthur was not writing about the agricultural landscapes of ancient Greece, but he was tying a predicted astronomical shift to a hoped-for change in society at large. If the Age of Pisces coincided with the birth of Christ, the Age of Aquarius was a new dawn rising, a potential step away from the behaviour and attitudes associated with Christianity: patriarchy, hierarchical beliefs, suffering, guilt, repression, the pain of Christ on the cross. With Haight-Ashbury flourishing before him and the new millennium approaching on the horizon, it seemed to Arthur the right time to shed these beliefs, re-write the rulebook and rebuild something like the Golden Age; to live, as Hesiod would put it, ‘like gods with carefree heart’.22

Arthur was not the only one to make such pronouncements, nor was he the only writer to have an impact on the esoteric thinking of the counterculture. As Lachman has shown, the 1960s saw a revival of interest in previously obscure magicians and mystic writers. Thanks to the availability of mass-market paperbacks like Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier’s The Morning of the Magicians (1960), adventurous sixties readers were able to get a crash course in the work of Madame Blavatsky, P.D. Ouspensky and George Gurdjieff, among others.23 Another person of interest was the British writer and occultist Aleister Crowley. A regular name in the scandal sheets of the inter-war period, Crowley’s public status as a ritual magician, drug user and general libertine earned him the enduring title of ‘The Wickedest Man in the World’. In 1903 Crowley married Rose Edith Kelly and embarked on a long honeymoon trip that brought them to Cairo in the spring of 1904. There Crowley claimed to have established contact with his Holy Guardian Angel, a disincarnate entity he called ‘Aiwass’. Aiwass allegedly spoke to him over the course of three days and Crowley incorporated these messages into his doctrinal text The Book of the Law (1904).

The Book of the Law became Crowley’s mission statement in which he outlined his system of magic and the religious philosophy he called ‘Thelema’. Named after the Greek word for ‘will’, Thelema directed its followers towards the realisation of their true ‘will’, a sense of calling, purpose and identity that exceeds one’s own conscious desire. History, according to the Thelemic worldview moves through a series of religious phases or ‘aeons’ characterised by different spiritual practices. What Crowley announced with the publication of The Book of the Law was the latest shift in this cosmic calendar, the inauguration of a new aeon. Where Arthur plotted the shift of ages astronomically according the sign of the zodiac, Crowley took his cue from the Egyptian mythology linked to Cairo and the supernatural voice of Aiwass. The new aeon was dubbed the Aeon of Horus, and Crowley believed that it was his ‘will’ to act as its herald. In the Egyptian pantheon Horus is the offspring of Isis and Osiris, a falcon-headed god associated with the sun and the sky: a powerful deity of light who casts away all darkness. To Crowley, Horus was the ‘crowned and conquering child’, a dynamic, unruly deity who symbolised a movement away from the religious orthodoxies of previous aeons, the goddess worship of Isis and the patriarchal authority of Osiris. Although he was drawing on a very different mythology, in announcing the Aeon of Horus, Crowley was expressing a conviction similar to Arthur’s hopes for the Age of Aquarius: the world was on the cusp of a great change, one that would see the old order come to an end and a joyous new way of life take its place.24

Crowley, who died in 1947, is one of the many famous faces chosen by the Beatles to appear on the album cover for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967). He stands in the top left corner nestled between Swami Sri Yukteswar Giri and Mae West. Beyond this fleeting appearance, his work more readily fed into the fabric of the counterculture by way of another Haight resident, Kenneth Anger. Anger, a dedicated follower of Thelema, is a filmmaker and occultist who places himself firmly in Crowley’s lineage. Anger’s signature style is a combination of high-camp, esoteric symbolism and an abiding fascination with the inner workings of secret groups and coteries. His 1954 film Inauguration of the Pleasuredome shows LA’s occult celebrities performing a series of luxurious rituals. In Scorpio Rising (1963) Anger fetishised the black leather and chrome that formed the erotic core of Marlon Brando’s performance in The Wild One (1953). Kustom Kar Kommandos (1965) did much the same for hot rod enthusiasts, and both films displayed Anger’s pre-MTV ability to match vivid images with choice cuts of pop music.

The mid 1960s found Anger in Haight-Ashbury living in the Russian Embassy – not the actual embassy – but one of the Haight’s legendary palatial houses that also doubled as a venue, thanks to its large ballroom on the ground floor. Anger lodged there along with the usual crowd of musicians and artists, and he began work on a film called Lucifer Rising. It would be 1980 before the film was complete after undergoing numerous changes in direction and personnel. The version he worked on between 1966 and 1967 was to be an expression of his belief that cosmic history was about to move into a new phase. In throwing the name ‘Lucifer’ into the counterculture’s melting pot of references and symbolism, Anger was invoking the rebellious archangel of Christian myth and John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost (1667). Lucifer is a fallen angel, the bright star who is cast out of heaven after challenging the authority of God. Landing in hell, he becomes Satan, God’s adversary. Like Horus then, Lucifer is a figure of disobedience, another deity who goes against the law of the father. For Anger though, the attraction of Lucifer lay in his ambivalence. He is both angel and devil, the ultimate bad boy, good precisely because he is so wicked: a kind of biblical James Dean.

With Lucifer Rising, Anger was celebrating the power of this beautifully defiant attitude. If the new dawn was to come it would require such a shining star, or better still a cadre of such figures to light the way forward for the rest of the world. Anger found such heralds in the Haight’s vibrant artistic scene. In particular, a young musician called Bobby Beausoleil seemed to Anger to typify the rebellious Luciferian spirit. Depending on which source you read, Anger first met Beausoleil at ‘The Invisible Circus’, an orgy organised by the Diggers at Glide Memorial Church in February 1967, or at the Brave New World, a gay bar in Los Angeles, sometime in 1965. Either way by early 1967 Beausoleil had become Anger’s protégé and a fixture of his life in San Francisco. Beausoleil opened the city to Anger and brought like-minded people into their developing circle. With Anger’s encouragement, Beausoleil took on the film’s central role of Lucifer, and he began to work on a suitably epic soundtrack for the project, a potent mix of Wagner and psychedelic rock. In September 1967, the pair celebrated the autumnal equinox with ‘Equinox of the Gods’, a live show that featured Anger performing magical rituals alongside Beausoleil’s music. The event was filmed, and Anger originally planned for the footage of him in full flight to be included in Lucifer Rising. He intended for this material, coupled with footage taken at the Russian Embassy showing a ‘Wand-Bearer’ presiding over a group of acolytes, to show that within America’s post-war demographic, ancient knowledge had become indigenous to the children of Horus. In other words, the Age of Aquarius would be brought about by the new culture of the young.25

Landing in March 1967, Manson would have benefitted from the day-to-day markers of the Haight’s cultural independence – crash pads, street charity, legal clinics – but he also would have been able to bask in this harmonious sense of goodwill, the positive energy generated as the area transformed into the symbolic capital of the counterculture. He looked the part, he carried – along with practically every other new arrival – a guitar on which he played his own songs, and with a headful of the Beatles, Robert Heinlein and L. Ron Hubbard, he quickly tuned into the Haight’s wavelength. With its communes, its cosmic mysticism, its emphasis on free sex and its clear desire to challenge the social mores of the day, Stranger in a Strange Land already had its place in the Aquarian mindset when Manson arrived. Indeed, one of Heinlein’s Martian coinages, the verb ‘grok’, meaning to know or to understand something to the point of absorption, had by 1967 become part of what Jay Stevens has called the ‘hippie sprecht’. This ‘charged code’ helped to mark out one’s membership of the counterculture while also succinctly expressing its key ideas. Manson grokked the Haight and the Haight grokked him back.26

That said, a listen to Manson’s music indicates that his thinking was moving in a different, darker direction than that plotted by the Be-In and Gavin Arthur’s speculations. Early songs like ‘Sick City’ with its ‘restless’ speaker desperate to leave the uncaring, miserable town that’s ‘killing’ them initially seems like a straightforward blues number. Having taken to the guitar while in prison before honing his style busking on the streets, it’s not surprising that Manson’s initial efforts would comfortably fit within a tried and tested mode: a song about the misery of privation and the desire for a better life. Where other songs of this type, Bob Dylan’s ‘Down the Highway’ (1963) for example, involve the singer stating their problems to move beyond them, the lyrics of ‘Sick City’ boil with rage and confusion. The ‘restless people / From the sick city’ are said to have ‘burnt their houses down’, a spectacle that makes ‘the sky look pretty’. On one level this is restlessness taken to the extreme: people set fires across the city because there’s simply nothing better to do. On another, Manson seems to be singing about an ominous social divide. Shut out of the city’s affluence, the restless take destructive revenge upon those who seem to have it all.

‘Cease to Exist’, a song Manson wrote and recorded in 1968, lacks the overt aggression of ‘Sick City’ but is equally sinister in its evocation of a smothering psychodrama between its speaker and a ‘pretty girl’. With such unremarkable platitudes as ‘I love you pretty girl / My world is yours’, there’s initially little to separate the lyrics from any number of sugar-sweet pop songs. Just as he had heard the Beatles do it on The Ed Sullivan Show with ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ (1964), Manson expresses his love and looks for it in return. With the Beatles though, however intense the hormonal rush is that propels the song forward, the address remains politely chaste. In asking ‘please … let me be your man’ and ‘please … let me hold your hand’, their song is about permission just as much as it is about desire. Not so with ‘Cease to Exist’. Here, the expression of love is not just hyperbolically overwhelming but an outright act of domination. The invitation is for the pretty girl to ‘Give up [her] world’ by recognising that ‘Submission is a gift’. There’s a fair amount of grokking going on, but it’s an annihilating process in which the identity of Manson’s speaker eclipses that of the girl: ‘I’m your kind / I’m your mind / I’m your brother’. ‘Cease to Exist’ is the Beatles filtered through Heinlein, Hubbard and the group mind that was taking shape in Manson’s Family: a pop song designed for a cult.27

Compare both ‘Sick City’ and ‘Cease to Exist’ with Jefferson Airplane’s ‘Somebody to Love’ (1967) and Manson’s divergence from the general ethos of the counterculture becomes clear. Recorded for the band’s second album Surrealistic Pillow (released one month after the Be-In in February 1967), ‘Somebody to Love’ has, together with ‘White Rabbit’ (1967), become one of the classics of the era. Written by Darby Slick for his band the Great Society, the track was originally recorded in 1966 as ‘Someone to Love’ before vocalist Grace Slick graduated to Jefferson Airplane and took the song with her. Combining folk music and psychedelic rock alongside a soaring vocal performance, ‘Somebody to Love’ conjures up a scene of discord and despair: truth found to be lies, joy dying inside and gardens of dead flowers. Darby Slick had just broken up with his girlfriend when he wrote the lyrics and was clearly working through his angst. Out of this misery though, having ‘somebody to love’ becomes a matter of survival, a necessity when times are bad. Across the song’s catalogue of problems that range from black moods to false friends, a bond with ‘somebody’ else is offered as the all-purpose solution. It’s a simple message that would be utterly naïve were it not for its relevance and applicability at the time.28

By 1967 American troop deployment in Vietnam stood at 485,000. Despite this heavy presence it appeared that little strategic progress was being made and American, South Vietnamese and North Vietnamese forces were merely becoming bogged down in a protracted and increasingly bloody conflict. In response, domestic anti-war protest and equivalent movements in the UK were becoming vociferous in their opposition. While 1968 would see these passions boil over into aggressive public demonstrations, 1967 was marked by some exemplary acts of non-violent protest. ‘Flower Power’ (1967), a photograph by Bernie Boston originally published in The Washington Star, shows a young man placing a flower in the barrel of a rifle held by a military policeman. The confrontation occurred in October 1967 during a march on the Pentagon organised by the ‘Mobe’ or National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. This was the event documented by Norman Mailer in The Armies of the Night (1968) during which Allen Ginsberg, Ed Sanders and a contingent of the amassed protestors attempted to ‘levitate’ the Pentagon building as a means of ‘exorcising’ the ‘evil’ it contained. As well as neutralising conflict on the day, the offer of flowers also helped to set out the Mobe’s political standpoint: violence was not an inevitability, it was a choice. This is beautifully captured in Boston’s image. The gesture of the young man is a refusal to engage in violence, an attempt to show that empathy and compassion can win out over combat.29

Although any mention of ‘love’ in a countercultural context invariably suggests vague ideas of ‘free love’ and sexual indulgence, the line of thought leading from Jefferson Airplane to ‘Flower Power’ was much more expressive of a humanitarian philosophy. The same potency coloured phrases like ‘Summer of Love’. Overused as a media caption, it is often unclear exactly what this describes or even if it took place at all. That said, as the Haight swelled to bursting point during the middle of 1967 with travellers, tourists and college students alike making it a site of pilgrimage, the hastily convened ‘Council for the Summer of Love’ tried to ensure that the community could cope. As Danny Goldberg describes, notices in the Oracle ‘exhorted all new visitors to bring warm clothing, food, ID, sleeping bags and camping equipment’. This was not the invitation to the orgy that new residents may have expected or hoped for. Instead, the encouragement was towards a duty of care. To love one another means to live in harmony, to make the experimental community work and thereby demonstrate to all who care to look, that another way is possible. Treat the next person along as your sister or brother, show them respect rather than suspicion, and there will be no need for words like ‘enemy’.30