Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

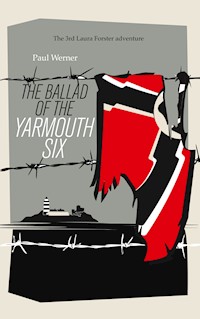

Laura Forster´s doing it again. The third volume follows her, with some anticipation, to the Channel Islands, in the Bay of St. Malo. Here, she is busy unveiling a dark secret ultimately harking back to the German occupation during WW II. The focus of her investigations lies on the history of the legendary Yarmouth Six: a jolly band of six young expendables recruited from a notorious "juvie". Under the leadership of an inexperienced lieutenant straight from Sandhurst, they are to mount a "pinprick" commando raid on the heavily mined little island of Sark. A suicide mission, obviously, that soon runs into heavy waters and comes very close to a fubar end. One of the recruits drowns; others sustain gunshot wounds. When, finally, it´s each man for himself, the generalized confusion gives rise to a fair number of dreadful, shocking, but also rather hilarious episodes, laughter being deadlier than bullets. Once the war is over, the six survivors, who had narrowly failed to become the terror of the Nazis, decide henceforth to take better care of Number One by founding a brotherhood of crime, which, in turn, is to become the terror of the British Isles. All of that is a lot of water under the bridge. Or is it? A long and bloody trail appears to be leading from the six graves to a mysterious present-day murder spree. When, in the course of his vendetta, the killer shoots a certain Solveig by way of collateral, he´s made a bad mistake. Young Solveig happened to be the first great love-affair of Laura Forster´s adoptive son, Ignace. And God knows, the Forster family is not in the habit of taking such things lying down...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 690

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

First Chapter

The Wily Minx

At Fjord's End

Islands in the Stream

Second Chapter

An Inspector Calls

Singin' on the Train

The Malvins

Third Chapter

Double Jeopardy

The Citadel

The Treasure Trove

Fourth Chapter

The Cave

The List

For a Pocketful of Marbles

Fifth Chapter

The Left Arm of the Lord

The Overcoat

Gaston de Lyon

Sixth Chapter

Road to Salvation

Gefillte Fish

The Toad

Seventh Chapter

Betty Boop

The Ship

The Fox and Ferret

Eighth Chapter

The Deal

Calypso's Bridal Den

Each to their Own

Ninth Chapter

The Seventh Little Indian

Rose of Sark

Enter Mr. Goodfellow

Tenth Chapter

Gilbert and Sullivan

Daphne's Realm

Jack in the Box

Eleventh Chapter

Pluto's Moons

Hopscotch

Crawl

FIRST CHAPTER

1. The Wily Minx

The tiny, silvery shining fishing boat dances on the frothy crests of a confused Atlantic cross sea like a hooked swordfish desperately fighting for its life. The remaining distance to the island, whose savaged surface is gaping like a festering wound in mid-ocean, amounts to no more than half a mile. First surging breakers are literally exploding on the low-lying cliffs furthest offshore, their protective ring having only recently been overwhelmed by the devastating power of a hurricane surge.

The two tall, skinny, hollow-cheeked adolescents aboard the boat seem to have drifted into these Caribbean waters straight from the coasts of Africa. At present, they are having all the trouble in the world just to stay on their legs in the billowing waves. They had better though, since sitting down, they would lose control and more likely than not ram their boat into the belt of reefs. As if foul-tempered Poseidon was grudging them even their puny clothing, malicious squalls carrying more than just a whiff of putrefaction keep tearing away at their shoddy rags, singed by the sun and kept together but by layers of sticky salt. With reddened eyeballs, the two of them are fiercely focussed on penetrating the wet curtain of fine spray swooshing over boat and crew whenever another wave bursting with a fierce blow on the boat's bows makes the hull shudder.

The men are in dire need of a breach between the columns of green water shooting up, now here, then there, in front of their salt-burnt eyes like so many playful geysers. One of the two, standing somewhere between the bows and the primitive control column complete with lever and wheel, is desperately holding on to a piece of thin rope, whose loose end cuts deeper into the flesh of his right hand with every jolt of the boat. His mate is clutching the small wooden steering wheel, whose violent jerks threaten to dislocate or break his fingers.

Finally, they make it. Due to sheer luck rather than skill, they manage to give both Scylla and Charybdis the slip and to leave the turmoil of the raging sea behind. Their almost keelless surfboard of a boat glides into the natural haven of a shallow lagoon. Before the hull touches ground, the man at the wheel performs a brusque 180-degree turn, veering the bows into the wind, so that the boat comes to a dead halt within seconds. Then he signals his mate to kick the rusty heap of scrap-iron that serves them as an anchor overboard. While the boat is fidgeting this way and that as if only too eager to break away from this ghost of an island, the two men take up their machetes, blunted and corroded by the vitriolic air as their dull metal is, and pick up two powerful police torches in protective plastic wrapping. Then, they both shoulder knapsacks that look as if they were stitched together from motley pieces of canvas and, pulling on the anchor line once again to make sure the contraption will hold, nimbly climb overboard. Sinking into the greenish water up to their hips, they wade ashore as if on stilts.

Still breathing heavily from the effort of climbing up the sands that offer little foothold, they decide to sit and rest on the bit of beach stretching some fifty yards to the left and right of their improvised roadstead. For a magic moment, the sun, hurrying towards the horizon as if trying to catch up with the loss of time incurred by watching the manoeuvres of the two blacks, briefly immerses the beach in the soft, velvety light of the notoriously brief Caribbean dusk. The two men look out to the sea while munching some mushy crusts of bread, bits and pieces of fried fish they brought in their knapsacks together with two bottles of drinking water each. At long last, they stand up and, almost hesitatingly, muster the island they have so far been turning their backs on as if lacking the courage to face a ghoul.

In the rapidly waning daylight, the small, flat island, whose highest elevation barely bulges over the sea's surface, presents itself to them like a piece of raw flesh brutally ripped from a dying whale's huge corpse. The breath-taking stench that poisons the air stems, not from a drowned cetacean, but from the host of dead fish landed by the surge and, which, after much vain thrashing and floundering, suffocated miserably in the heat. True enough, the island never really was the most precious pearl in the string of Caribbean beads called the Lesser West Indies. Whoever went out of their way to visit it would have to be longing for time out from the hubbub of the madding tourist crowds. At this very moment, however, deprived of even its most modest natural charms, it resembles a pestilential blob that burst and turned inside out. Not so long ago, a murderous surge of gargantuan proportions swept across the low-lying, almost defenceless island flooding it, while the inexorable twister of a cyclone sheared off anything higher than two feet over the ground as if with a giant sickle. Palm trees, shrubbery, cactuses, in short, the entire local flora, sparse and tough though it was, got bent, broken, cut, uprooted and blown to high heaven. Brick and gingerbread houses, bungalows, huts, the odd colourful chapel of this or that denomination literally disintegrated, bits and pieces being scattered all over or piled into heaps of crushed wood, cardboard, and plastic. Road and traffic signs, billboards offering scarce real estate for sale were ripped from their wooden posts and concrete fixations and torn apart like so many worn sails.

The island's sole town was, to all practical purposes, destroyed, deleted from the maps. If it weren't for the lack of bomb craters, one would have attributed this state of utter annihilation to carpet bombing rather than the destructive force of nature unleashed.

Like giant feather dusters, the tussled crowns of uprooted palm trees have spread across large parts of the debris like a cloth over a corpse. A touching but pointless gesture, for there isn't much to hide. Even a look from space is likely to reveal the mercilessness with which this category four hurricane vandalized the island. What used to appear like a gleaming green leaf dancing on the cobalt blue sea has brutally been reduced to a withered water lily.

The fact that no human beings were harmed here is due to precautionary measures based on painful experience. Days before the hurricane, moving along its hardly predictable humming-top route, reached the island, local authorities ordered its hurried evacuation. To the last man and woman, its inhabitants were shipped to its partner island situated further south. Not because that one was presumed to escape the cyclone, but because it boasts a number of concrete buildings, schools and churches with hurricane-resistant basements, all of which had stood the test of prior cyclone afflictions.

Harsh administrative coercion is inevitable on such occasions since not all inhabitants will listen to the voice of reason. Nobody likes to leave their personal property behind, even if only for a few days or the odd week. After all, who knows how much of it they will find again upon their return. Money, jewellery, and other valuables of little bulk and weight the islanders, many of whom had never before left the place even for a day were obviously allowed to take with them. The rest of their belongings including a sizeable number of seriously perturbed pets they had to leave behind and hope against all hope that, this time, the raging elements would not sweep their home into the sea.

The property reluctantly left behind is an easy enough prey for looters such as these two adolescents who obviously haven't come here to offer their condolences. Yet, despite greed and avariciousness obfuscating their brains, even they are impressed by the grisly vista of this horrific scenery. Frequently looking back over their shoulders with uncouth anticipation, they cautiously approach the centre of devastation. Even the moon seems to be shrouding her face with shame. Myriads of stars, sparkling like so many ice crystals in the black void, are impassively blinking down on the righteous and villains alike. A thick cover of dark clouds restlessly chasing across the skies is approaching so fast you would think they have been lying in wait all day to be finally released like a swarm of hungry bats at the first sign of nightfall. Down South, fierce flashes of lightning are darting across the horizon.

The two looters have switched on their torches without freeing them from the semi-transparent plastic wraps. Their cones of dimmed light scurry across the sundry pieces of debris blocking their way. Where precisely public roads end and private properties start, the two of them can only guess. Here and there, they half-heartedly poke about in splintered wood, broken glass and scattered, foul-reeking rubbish with their primitive machetes. Every now and again, they stoop to pick up some promising item only to reject it after a short desultory examination. Logistics is essential. Their knapsacks being smallish and their boat anything but spacious, the men do not want to burden themselves with bulky or heavy stuff of any description.

Abandoned and left to their own devices, dogs will scupper their relatively civilised behaviour almost as fast as their respective masters. Instead of barking away as they have been taught, they will, sooner rather than later, fall back on the wolfish howling anchored in their DNA. As unimpressed as the pilferers seem by such heart-rending arias of hunger, any other, less easily identifiable sounds make them they react with both immediacy and violence. Time and time again, they freeze in mid-movement as if momentarily turned into the proverbial pillars of salt and listen in the darkness with great intensity and concentration.

The risk of some islander having dodged the evacuation measures with the express purpose of catching or killing looters and robbers such as these seems small enough to be negligible. Then again, life is full of little surprises. Take the example of one good-for-nothing, petty thief and certified wino, whose improbable story has been told and re-told in the bars of the Lesser West Indies for the last hundred-odd years. One fine day, this scallywag of a loser had, once again, been flung into the one-cell prison of Le Carbet or some such place on the island of Martinique. Nothing to it, except on that self-same day the neighbouring volcano decided to throw one of its more massive tantrums without having given fair warning. So, when this pathetic wreck of a human being had done with his post-debauch prison slumber, he had found himself, to his dismay or relief, to be practically the only survivor left in a town covered with layers upon layers of lava and smouldering ash.

And so, the possibility of this or that stoned-to-death junkie without next of kin having crawled into some obscure hole to sleep it off while the island was being evacuated can perhaps not be discarded altogether. And there is the outside chance of some competing pilferers being at it, simultaneously, as it were. On their way here, the two men have seen no other boats out at sea. But that doesn't mean a thing. Small boats lying deep in the water are hard to spot in the Atlantic swell. For the time being, though, sea gulls, dogs, rats, and cats seem to be their only competitors around. And they still have enough dead fish to feast on. Wide-open animal pupils time and again reflect the light beams of their torches like crystals of quartz in the pitch-black gallery of a diamond mine.

Every now and again, the men are startled by the grinding sound of a piece of cardboard or plywood swept across a free spot of asphalt by a sudden squall. Doors hanging askew on their creaking hinges are flapping open and shut in the wind. The far roll of thunder announcing a sluggishly approaching storm is slowly growing louder, more threatening.

Here and there the two looters stumble over animal cadavers, cats and dogs drowned or put down by their masters. Their owners probably thought they were doing their best friends a last service by shooting them instead of allowing them to be swept into the sea and torn to pieces by sharks or barracudas.

Finally, the tropical storm has reached the island and starts discharging its unfathomable quantities of water on the pilferers who are helplessly exposed to the big drops literally exploding on the bare skin of their torsos so that, soon enough, they resemble two giant poodles just returning from the shear. Forked flashes of lightning race across the night skies and lend an additional element of drama to the eerie scene. Volleys of close claps of thunder that sound as if produced by violently shaken giant slabs of sheet metal are rolling through the narrow canyons between the mounds of rubbish.

If they feel any pangs of conscience profiting from the plight of others, the two men don't show it. Then again, why should they? From their point of view, even in the best of cases, they will take no more than a dwindling portion of what their African forbears were once stripped of on the island in terms of blood, sweat and tears.

The first tenants to leave their stamp on the island, more recently belonging to the English crown, were the honourable, God-fearing brothers John and Christopher Codrington. It was they who gave their unlikely name to the island's sole settlement, a name that fits the rest of the flowery Caribbean toponymy like an insipid pair of sheep's eyeballs would fit a spicy Cajun gumbo. The commercially inclined English monarch of the time, probably Victoria the Indestructible, must have popped the corks once her very own Privy Council had managed to find two such perfect simpletons as the Codrington brothers willing to pay a handsome sum for the long-term tenancy of this utterly useless little island. To embark on a sugar cane, cotton, or banana plantation, Barbuda's marshy soil was as unfit then as it is today. And yet it soon transpired that the Codrington brothers apparently were not as feeble-minded as all that. Because the one thing the island had plenty of was unused vacant space. Which, in turn, could be exploited for the provision of the one species of raw material, without which any economically viable operation of plantations anywhere between Trinidad and Charleston, say, was not feasible - cheap labour.

Whether or not the Codringtons really did "breed" their slaves like you would cattle, as is maintained by some historians, remains a moot point. Strictly speaking, it would have sufficed for them to maintain the necessary conditions under which the black folks would obligingly multiply at the desired rhythm. What can safely be assumed, though, is that the Codrington brothers made a fortune from selling slaves on the markets of all the other islands above and below the wind.

What gave the brothers their sharp competitive edge was the fact that their slaves had been born and bred in the Caribbean and were, hence, adapted to and familiar with the local conditions, both climatic and otherwise. Because it was not least the humid heat spawning all sorts of disease and epidemics that would time and again kill off black folks who had been rounded up in some arid African region and shipped across the ocean in ships famous for their abominable squalor. They who were born on God-forsaken Barbuda, however, could be put to work on the plantations practically from an infant age, thus promising an unusually long working life. A win-win situation, in other words. Not for the blacks, of course, but for the Codringtons and their clientele.

The moment the looters seek shelter from the relentless rain under a piece of corrugated-iron roofing wedged in a slanting position, the slightly taller man stops his mate by pulling him back on his arm. Thus, immobile for a few seconds, they resemble a shiny ebony double sculpture with thin rivulets of rain water running down their body to form rapidly widening puddles at their feet.

When the pelting rain momentarily subsides, his mate, too, catches the ominous sound. A low whimpering kind of groan like that emanating from a creature breathing its last. It comes from somewhere in the heap of debris to their left. This being the direction whither they just came, they are left with a riddle. If someone is dying there, they must have overlooked him, which, even given the combined handicap of darkness and rain, seems unlikely. Very cautiously, their machetes held ready to strike, they retrace their steps.

Then, they suddenly stop with all signs of horror and the next moment assume a back to back fighting stance. An atavistic reaction planted in the DNA, perhaps, going back to the days of tribal warfare on the African plains. When there is not an attack forthcoming, they slowly relax again. The cones of light from their torches dance across the face, streaming with blood, of a white woman. Fatally injured, it would seem, she managed to crawl into the den created by two destroyed bungalows that have literally been folded into one another. Not surprising, then, that the pilferers didn't notice her first time round. Maybe she was unconscious then, anyway, and didn't produce that eerie groaning sound yet. Woken by the claps of thunder and the pelting of rain on the debris all around her, she probably woke up for a last time just now.

The looters scan the immediate neighbourhood to see whether there are more injured or walking dead anywhere. With obvious relief, they find that this is not the case. The woman has been shot at least once. Blood is trickling from a small entry wound above her right eye and, running from her forehead, nose, and chin, is dripping onto her T-shirt already tainted a darkish red. Where she comes from and how she managed to drag herself here despite her gun wound remains her secret. Sometimes the human body, frail as it may seem on the whole, is nevertheless capable of stupendous feats. The taller of the looters bends down to her and addresses her in English. Her facial expression seems to express understanding, alright, but at the same time, she is far too weak to speak. The only thing she is capable of uttering is that awful heart-rending groan of hers, soon turning into a rattling and wheezing. With great effort, she seems to be forming a word that the two blacks do not understand.

The looters hold a short sotto-voce war council. Their scarce knowledge of the human anatomy in general and the female one in particular, does not allow them to pronounce a more substantial verdict. But despite their youth, they happen to have come across dead and dying and hence recognize a goner when they see one. One way or another, they have absolutely no interest in keeping an eyewitness of their despicable activity alive. The taller one, who tried to talk to the woman a moment ago, now touches his machete and gives his mate a questioning look. His companion shakes his head. He probably knows the sad business of finishing the woman off will be assumed by nature herself. It would be far more useful to learn where the injured woman has come from and what happened to her. She doesn't look like a looter herself but doesn't really give them the impression of being a resident of Codrington either. A tourist specializing in voyages to catastrophe-stricken areas? If she was attacked here, which seems more than likely, the culprit could still be around somewhere.

As though the woman has followed the pilferers' short exchange by reading their lips, she raises her right arm and points

to her left, in the general direction of the sea. The taller, more active of the pilferers, jumps on one of the heaps of debris and, by dint of a few dexterous hops, skips, and jumps manages to climb to the peak of the rubble. Once in his precarious position up there, he holds his hand horizontally against his forehead at the level of his eyebrows to form a protective shield against the endlessly pouring rain. Thus, he scans the area for whatever it was the woman intended to indicate to them - a vehicle or vessel of sorts, anything capable of throwing some light on this mystery.

And it would seem his efforts are crowned by success. When he climbs down again, he realizes the woman is dead. His mate closes her wide-open eyes with their glance turned inwards.

They leave the corpse behind in that reclining, half sitting, half lying position. There is neither time nor adequate space for a funeral. The men have come with the beginning of the ebb tide and had better be off the island again at the next high-water mark lest they have to make their way through the razor-sharp reefs at low water and doubtful light conditions. That would be foolhardy for anyone but the most experienced locals, an exclusive club which those two are not members of.

They turn their backs on the rubbish heaps and wade through the lagoon whose water reaches to just about their navels. The narrow band of shallow water is separated from the sea proper by no more than a narrow sandbank some twenty yards wide. In a matter of minutes, they have reached the beach. The rain has stopped. The storm has abated to a festival of silent summer lightning moving North. The increasing density of atmospheric layers near the horizon causes the lavish multitude of twinkling stars to thin out at about sea level. Yet enough celestial bodies remain to render the silhouette of an unlit sailing yacht just about visible against a generally dark background. Moored not far from the beach, it's bobbing in tune with the gentle night swell of the ocean.

The looters point their torches at the yacht. The light beams reach far enough for the men to realize the boat's hull is white. Now they begin to have an inkling where the woman came from. What they still don't know is who shot her and why. The yacht must have arrived sometime after the passage of the hurricane, so much is for sure. It would not have survived the way she is anchored there, without even the sorriest excuse for protection. No adequate hurricane holes have ever been reported on pancake-like Barbuda.

The fact that the yacht doesn't display anchor lights doesn't mean much at all. Passage-making crews tend to be rather willing to do just about anything to reduce energy consumption. Since the island is situated outside the more popular West Indian routes and represents little or no interest to fishing vessels, there is virtually no risk of collision for a yacht anchored here without her masthead lamp lit.

Far more remarkable, however, is the total lack of light below. Add to this the fact that the metallic clew of the genoa, partially unrolled by the tearing wind, keeps knocking against the aluminium mast in the swell without anyone getting sufficiently worked up by the noise to get up and do something about it and what you get is a thoroughly unusual, if not suspect situation. You would have to be very fast asleep, indeed, not to feel irritated by the constant bell-like toll of the clew at some stage. A modern glass-fibre carbon hull makes for a splendid resonance body amplifying even the most discrete contacts with it above or below deck more effectively than any ghetto-blaster. There is something definitely not right with this yacht, this much the two looters conclude instinctively.

Again, they hold a short pow-wow, at normal volume this time. If they want to have a closer look, they will have to swim across to the yacht and climb aboard. That could be riskier than it might seem. Whoever is aboard the boat might be responsible for the woman's death. If so, he or she will have as little interest in eye-witnesses of their doings as the two pilferers. Then again, the dead woman could have been roaming the oceans single-handedly and happen to have been robbed and shot by pirates shortly before the pilferers arrived. The pirates may have left her for dead and departed in their own vessel, carrying off what booty they may have found on the yacht. In which case the boat, in all its apparent splendour, would have to be judged as abandoned.

Without knowing their way around the complexities proffered by the law of the seas, the two of them seem to have heard of substantial fees paid by insurance companies to those who manage to salvage and bring into safe port a vessel that would otherwise clearly have been lost at sea. Always provided the vessel was insured at all and had sufficient coverage. In such cases, the fee, high as it may seem, will always represent but a fraction of the price of an adequate replacement yacht. Hence, any insurance adjuster in his right mind will be only too glad to fork out the respective amount without necessarily asking too many questions.

Such dizzying expectations way beyond what they could ever have hoped for scatters their initial qualms to the wind. Anything is better than having to act like scavengers and compete with dogs, rats and God knows what else in the race for useable rubbish. They drop their knapsacks in the sand, hang their machetes round their necks and, after a few yards' wading again, plunge headlong into the deeper, calmer part of the surf.

By the mere look of it, they have no great experience swimming, but don't really have to either. A dozen or so paddling strokes take them to the anchor chain which they cling to for a moment, huffing and puffing and spitting out salt water. Having soon recovered from the physical effort, they reflect on the boarding aspects. Groping along the immaculate, slippery hull, they find their way aft. The yacht has an overall length of some fifty-odd feet. In many Northern European marinas, that kind of size would qualify for respectful glances tainted by a touch of envy. In the Caribbean, though, anything short of, say, a hundred feet can at best claim to dory status. Suffice it to point out that many sailing yachts tied to the pier at English or Falmouth Harbours, Antigua, sport masthead and spreader lights that do not display the usual nautical white lights but proudly present the red ones normally reserved for aviation. What better way for their owners to insinuate that the sky is the limit.

At the stern, the two looters about to turn into salvagers are received by a humming and whizzing wind rotor that helps to produce electricity. Of which, to all appearances, there must be a healthy surplus on board this vessel. Several solar panels, normally also producing current, have been folded and hung over the railing like washing on a line. Either they weren't needed today, or someone folded them at sunset. Which might mean that the killing of the woman was an even much more recent event. Another piece of bad news for the men: there is no bathing ladder hanging from the transom, something that would have facilitated their boarding considerably.

The Wily Minx, one of the two men spells the yacht's peculiar name more than he reads it out. Who the hell is Willy Minx, and why is his first name spelled wrongly? As her home port, the yacht's transom reveals a place called Sark. That's another riddle for the two men. What kind of a place is that, sounding like shark? Neither of them has ever heard of it. Nor can they identify the flag she flies: a red St. Andrew's cross on white ground, the left upper box red with two gold female lions, rather thin ones, whose whip-like tails stretch across their entire, ascetic-looking backs. Colourful stuff alright, what with the emaciated lions and all, but not half as fanciful as some of the Caribbean national flags they have seen between the two of them.

Giving up on that hopeless rigmarole, the men swim to the bows again and discuss alternative boarding methods. The options are few and far between, as it would seem. One of them will have to climb up the anchor chain. That is neither easy, nor, and more important, can it be done noiselessly. On the contrary, few articles of a boat's equipment are noisier than her anchor chain, whose galvanized links will, as a rule, be forever sliding to and fro in a lip-like device made of steel. The permanent rumbling, knocking and rasping is usually loud enough to wake the dead. Silencing measures, though perfectly possible, are not always desirable, at least not for the skipper. The grating sounds of the chain, irritating as they may be, especially for the crew bunking in the forward cabin, tend to be the first warning signs of a yacht going adrift after her anchor lost its grip. Hence, many skippers, placing safety over comfort, prefer to keep this additional means of alert intact.

The taller looter, who has already proved his sense of initiative by climbing on the rubble heap next to the unfortunate woman, now puts an end to the discussion by seizing the chain and climbing up hand over hand relatively silently. Then he crawls under the railing very much like a soldier would under some barbed wire and lies flat on deck for a spell, panting and listening. The sea water dripping from his lean body forms a trickle that runs back into the ocean by way of the scupper. Down below, not a sound, so far. Up on deck, the genoa clew keeps hammering its ghastly lonesome rhythm. After a while, the man gets up and tiptoes aft, to the transom, where he takes the small plastic ladder off its fixture and folds it down the transom to provide his mate with a more comfortable means of boarding the Wily Minx.

Clasping their machetes and torches, they scuffle over the teak deck which smells of moist wood. Even in the dark, the yacht looks and smells brand new. If it weren't for that faint whiff of sweet decay in the air. The double wooden door leading down the companionway has been left wide open, as if to invite them in. The closer they come, the stronger the sickeningly sweet stench of carrion grows.

Cringing with anticipation, they stick their heads in the opening and switch on their torches. As the cones of light flit down the companionway and about the saloon, they see nothing downright untoward at first. Everything looks more or less as it should in a well-kept yacht. Except for the man in shorts and T-shirt sitting on the lavishly upholstered bunk at the far end of the wooden table. His head has fallen backwards and is now reclining on the upper rim of the backrest as if the man just fell asleep, recovering from the strain of a long Atlantic crossing. What doesn't quite fit the peaceful image is the ugly reddish-black bullet hole in his forehead, right between the eyes. No blood trickling from it any longer, the man has been dead for some hours, it would seem. What little blood has run down the back of his nose, coagulated a while ago, now forming a thick crust in his moustache. It doesn't take the verdict of an experienced coroner to realize that this man, whatever his function aboard may have been, died instantly.

Bending down low, the two looters cautiously climb down the companionway. As they start inspecting the cabins one by one, they come across two more bodies, one male, one female. They, too, seem to have been executed with a single shot to the forehead from a small-calibre firearm. The killer appears to be a stickler for precision. No killing rampage here, no hard feelings involved at all perhaps, just clinical precision coupled with a total lack of empathy. Those were neither pirates nor drug traffickers ridding themselves of awkward witnesses. The two men agree on this being rather the work of a cold-blooded and very dangerous killer, probably operating alone.

Whatever happened here can't have gone down that long ago, else the bodies would smell a lot more unpleasant and, in these latitudes, be already covered with maggots galore. If there is any animal able to pick up the scent of dead meat almost before the killing has taken place, it's the bluebottle. The killer has had just enough time to disappear unnoticed. Maybe it was the looters' sudden appearance on the island that drove him off the boat, which he might otherwise have used to sail on to Antigua or some other place. Which begged the question how he would put his retreat into practice now

Maybe he came on some other vessel? The pilferers haven't seen any, it is true. But then, they were very much focussed on navigation first, and on rummaging through the debris afterwards.

One way or another, the men are now faced with a dilemma. Either they leave the yacht and its shocking contents behind as it is, or they decide to lay claim to the salvage fee. In which latter case they would have to sail the Wily Minx down Antigua way or take her in tow. It all depends on the state of affairs in the engine room, since neither of them has ever learned to move along on sails only, and neither wants to start practicing that now.

Also, they will have to come up with a plausible story about how and where exactly they came into possession of the yacht. With a solid dose of realism fed by dim experience, it doesn't take them long to grasp that neither their presence on the island, nor the massacre on board would argue in their favour. Hence, what they need is a waterproof plan "B". For instance, they could pretend they came across an abandoned Wily Minx adrift on the ocean and took possession of her as you would of a stray horse in the prairie. Which would mean they have to get rid of the corpses first thing. Sailing along with some bloated, maggot-eaten stinking bodies aboard would, in any event, be something to be rather avoided, anyway. At least there are no traces of a fierce fight to be removed. There just hasn't been any, funny enough. The unfortunate foursome must have been caught totally unawares and taken it sitting or lying down.

Which allows the assumption that they knew their killer. Knew him and trusted him at least sufficiently for him to take easy advantage of the situation. He must be so certain of his shooting proficiency he hadn't even bothered to go after the woman the pilferers came across among the debris. He knew she wouldn't get far, fatally wounded, on a deserted island.

The two of them climb back on deck to get some fresh air and discuss the next steps. Follow the money is what they finally agree upon. Whilst one draws a deep breath as if about to go diving, and lowers himself into the saloon, the other one swims ashore once again, where the woman's body has already drawn a pack of ravenous rats. When he gets back on board, he finds his mate has disposed of the three corpses, which are now floating in the water together with the dead woman he himself contributed. Sharks and barracudas won't be long smelling the bait.

The men finally tie the genoa clew and try starting the engine. It takes three or four attempts till the starter coil catches on and cranks the engine into life. If the fuel gauge can be trusted, which, usually being the first appliance to go, it manifestly cannot, they should nevertheless have enough diesel fuel in the tank to reach Antigua. They decide to go for it and tow their own boat, whose outboard engine is that much weaker than the fifty-six horse-power Volvo Penta of the Wily Minx.

As they approach the roadstead where they left their open boat hours ago, the dawn has just spread enough daylight for them to realize with no little amazement that their own vessel has gone and is nowhere to be seen. Did it break anchor or chain and go adrift? In that case, it may have hit a reef and sunk. They look at each other questioningly and finally shrug it off. Just another detail they will have to take into consideration when spinning their yarn.

2. At Fjord's End

"Name's Kurtz, Colonel Archibald Kurtz." The man behind the wheel of a silvery grey Cherokee Longitude turns the rear-view mirror in above his head so as to make it reflect his face and gives a hearty yawn. On the whole, he appears reasonably satisfied with what he sees: the portrait of a man in his sixties staring back at him with a critical mien and a very rigid, penetrating kind of stare.

They are the dominant feature of his physiognomy, his piercing, greyish-green husky's eyes that may befit a sledge dog but, when met with in humans, tend to make everyone look the other way. Besides, on closer inspection, his nose seems a trifle too long or too wide, or maybe both. "Kurtz" turns the mirror back and looks at his watch. He has another one hundred or so miles to go on this spectacular winding rollercoaster of a scenic road. Studded as it is with hairpin bends, breath-taking falls and steep rises along the northern shore of one of the longest and most beautiful Norwegian fjords, that's going to take him another two, two and a half hours of driving. Not counting possible further breaks like the one he's just indulged in to light his first cigarette of the day.

To his right, the rays of the noon sun are doing their level best to penetrate the greenish pea soup of the fjord's calm, silent waters. They will have to hurry. In less than an hour's time, the first long shadows of the high mountain ranges rising imperviously on either side of the fjord will start darkening the surface of the water and cool it down to little above freezing point.

To the driver's left, a quick succession of dark green meadows smelling of freshly mowed grass, picturesque crofts and the odd village situated at the foot of steeply rising, gleaming wet rock faces makes for the typical fjord-country landscape. Mountain peaks covered with thick layers of snow for most of the year send their icy melt waters down into the valleys in the form of thunderous foaming cataracts hundreds of yards long. Wedged in by solid, unflinching walls of granite and gneiss, the local population, "Kurtz" muses, would stand no chance of survival in the case of a huge tsunami sweeping along the fjords of Norway's Atlantic coast.

What would it take to trigger a catastrophe like that? Not that much, in fact. A minor earthquake would probably suffice. A few tremor-like shocks might trigger a landslide of gargantuan dimensions among those seemingly rock-solid masses of stone which, in truth, are perpetually on the move. The tsunami resulting from this would obliterate all life along its path.

Hence, people living here have a lot in common with those settling next to a would-be extinct volcano that will presumably never erupt again – except when it does, one fine day. Looking at it from that angle, it's strange to see something like it has never as yet been recorded. Whenever sober, the Vikings were rather taciturn people, not exactly given to much reading or writing, it seems. But surely, a tsunami would have found its way into some saga or edda of sorts, one would wish to assume.

"Kurtz" grins and slides a CD into the car's Old-School phono system. As the music catches on, he sways to the left and to the right in tune with the rhythm: if you'll be ma bodyguard, I could be your long-lost friend...The deeper meaning of some of those pop songs remains a life-long mystery to most mortals non-addicted to pop. With all signs of boredom "Kurtz" reaches into the glove-compartment, takes out his iPad and starts frantically running the fingers of his free right hand over the screen while holding the wheel with his left. He seems unwilling to devote more attention to the admittedly sparse local traffic than absolutely necessary. The fact that he drifts onto the left-hand side of the road every now and again seems to indicate he is not all that familiar with Continental European road traffic. Be that as it may, he seems oblivious to the danger caused by the local coaches that assume the lion's share of indigenous Norwegian public transport and have a way of treating any contraflows with an air of contempt.

The fjords have for a long time been known as the favourite holiday haunt of, in particular, German tourists. Among those, teachers and pensioners with survival campers and elaborate motor homes are predominant enough to take it away. The really well-off meet on board the ludicrously expensive Hurtigruten cruise ships whose popularity, for reasons unknown, shot up in the nineteen eighties and nineties.

What are these people hoping to find here, "Kurtz" wonders as he looks around and shakes his head. A country as rugged as its population, whose provincial self-sufficiency, Hamsun-like melancholic depression and wide-spread xenophobia have all found adequate expression in Edvard Munch's extraordinary Scream.

Basically, it's another case of the hen and the egg. Was people's mentality formed by the claustrophobic set-up of those enchanted dales or did those narrow valleys attract certain kinds of melancholy, hard-drinking individuals from the very start? A bit of both, presumably.

What with their almost stagnant waters and their one-sided access to the ocean, the fjords, as opposed to the sounds, open on both sides like human guts, form peculiar blind alleys halfway between a river and a mountain lake. Like rivers, they have always served the transport of men and merchandise. Like lakes, they tend to convey the feeling of almost transcendental peace and quiet, or, on bleaker days, cause the uneasy feeling of harbouring some dark and sinister secret. Either as base jumpers or as suicide victims, not a few folks, both Norwegian and alien, ended their lives by hopping or dropping from particularly well-known mountain spots along the fjords, such as the fabulous "Pulpit".

Even at the best of times, fjords are, of course, no way near the pulsating arteries which are the large rivers of Europe and the rest of the globe. Rivers, whose meandering whims helped form our landscapes and mindscapes in war and peace. The fjords could never be that, because of their lack of shores transcending the physical and mental borders between tribes and nations. Economically speaking, their failure was a foregone conclusion if only for the lack of a viable hinterland. A vital shortcoming that turned fjords into virtual blind alleys and practically condemned the Vikings to a life at sea, forever in search of business partners further and further afield. Did they discover America? Of course they did. Did it do them any good? Not that we know of. Which doesn't mean there aren't any irrefutable successes to be marked on the bright side. One of them is linked with the name of Russia, another with that of Normandy.

"Kurtz" lets out a snorting sound and looks at his watch again. For the umpteenth time, he then looks at his iPad, which has, for some minutes now, been adorned with the portrait of a youngish man in his mid-twenties. His somewhat complacent mien is made more easily bearable by being half hidden behind a dense mat of blond hair. Could he be gay? That's affirmative, "Kurtz" answers his own question.

"Hi there, Olaf, how's it hanging?" "Kurtz" addresses the portrait as if skyping with the blond, blue-eyed, sun-spotted latter-day Viking so completely and totally fitting the general idea of a Scandinavian. Or Aryan, for that matter.

"Kurtz" throws the iPad with the photo up onto the passenger seat and focusses on the road again, not without repeatedly taking sidelong glances at the screen as though he wants or needs to memorize Olaf's physiognomy for some future reference. Some people endowed with, or suffering from, a peculiar savant syndrome, are apparently able to remember every feature and detail of a face they may only have seen once, fleetingly, at that. "Kurtz" apparently doesn't belong in that category.

The next moment, he hits the brakes so hard that the Cherokee grinds to a brutal halt with screeching brakes and smoking tyres. Right in front of him, situated in a kind of dead-end hollow, his target location seems to be basking in the afternoon sun. That's it, your typical village at the end of the fjord, its nondescript character begging the question why in God's name anyone would take the trouble of coming here in the first place. "Kurtz" obviously has an excuse in the form of an errand to run.

He seems to have arrived somewhat earlier than feared. Deftly, he manoeuvres his Cherokee into a long-term camper and motor home parking site on the hill and places it between two manifestly unoccupied campers in such a way as to protect it from any inquisitive glances while having a good look at the village himself. As it points outward, it's furthermore ready for take-off any time without "Kurtz" having to turn or move it sideways first. On balance: had someone less experienced in such things devoted half a day to the search for the most appropriate parking spot to pick, they could hardly have hit upon a better spot than the one that came kind of naturally to "Kurtz" right away.

Beyond the road, the dirty grey and green waters of this arm of the fjord cutting deepest into the land keep washing over a patch of stony black shore. The somewhat bigger rocks of this former end moraine have a coat of dirty green seaweed, whose slimy tentacles indicate the state of what remains of the Atlantic tide once you are thus far removed from the ocean.

Svartdalen, the village, hardly more than a hamlet, really, is not an organically grown community with quaint but authentic wooden houses that are reminiscent of the clinker-built Viking long boats. This isn't Bryggen, either, with its stores, magazines, and workshops where leather was formed into solid mountaineering boots or iron forged into weapons and wooden poles turned into the legs of chairs and bedposts. Much rather, it's a Disneyland creation shaped on Alpine edelweiss models and stuffed with souvenir shops, cheap burger houses, Starbucks joints, run-of-the-mill restaurants and grotesquely pimped-up hotels with antler-adorned reception halls. Looking at the scenery from his vantage point on the hill, "Kurtz"

cannot help suspecting all of this phoney splendour will be dismantled at seven p.m. sharp by an underpaid mobile Pakistani worker unit to be handed on to the end of the next fjord arm, which the majority of tourists will home in on tomorrow.

"Kurtz" seems in no particular hurry. Again he gropes for the glove compartment and this time pulls out a small pair of binoculars through which he scrutinizes the flock of elderly people who happen to be taking to the road this very minute, sporting trekking gear of sorts complete with knapsacks and ski sticks. When he has seen enough, he puts back the binoculars and iPad and looks at his wristwatch.

The appointed hour of the rendezvous with Olaf appears to have come. He gets out of the Cherokee, stretches his tendons, muscles and bones and locks the door from a distance with the remote of his keys. Then he takes off his leather jacket so that his red turtle-neck jersey pullover makes him a coloured blot in an otherwise rather monochromatic landscape.

He looks around to check whether any local parking regulation might come in the way of his leaving the Cherokee to itself for a while, finds none and walks off. The village lives on bus and ship-loads of tourists. Hardly anyone gets here in their own car. Humming a tune to himself, he throws his jacket over his shoulder and continues on his way into the centre of the village. Apparently, he has a problem of sorts with his right leg, which he drags a little, so that his gait looks kind of wabbly. He stops here and there to take a look at the objects of desire displayed in this or that shop window. Finally, he enters the terrace of a café and looks around for a vacant table.

He is in luck. A young couple that has for some time been wiping away at their respective iPhone screens gets up and leaves the terrace. "Kurtz" takes possession of the table and orders a black coffee. While waiting for it, he turns his chair just enough to face both the road and the entrance of the hotel right across from the café.

The young trainee waitress has hardly had time to serve the cup of coffee with the usual footbath, when a coach stops smack in front of the hotel. Two dozen or so elderly passengers visibly plagued by the typical banes of old age such as sciatica, rheumatism and all sorts of orthopaedic ailments start leaving the coach.

"Where on earth did they go? Just to be sure to avoid the spot," "Kurtz" jokingly asks the waitress.

"Oh, they were all around thirty and fit as so many fiddles when they left this very morning," the girl answers.

"It's what our air does to people, so better take care not to breathe in too much of it."

"Kurtz" gives her a dry laugh and a wink, never losing sight of the hotel, though. Thus, when a blond young man turns round the coach all of a sudden with some aplomb, "Kurtz" immediately gets up, leaves a handful of kronor on the table and follows "Olaf' towards the far end of the village, the one opposite the campers' site on which his car is parked, that is. No doubt, this is the sun-spotted Aryan from the iPad. Maybe a year or two older, with just the suspicion of a developing embonpoint, but Olaf alright.

Dressed a little out of season with only a white cotton shirt, light blue jeans and brand-new sneakers, he doesn't look like someone hell-bent on a quick tour of the mountains. Not at this relatively late hour. More likely, he is heading for some lonely spot in the sparse grove of coniferous trees, whose first crippled specimens mark the end of the village - or its beginning, all according to which direction you happen to approach it from. In his right hand, Olaf carries a jute shopping bag dangling in tune with his firm, swift step.

"Kurtz" doesn't show himself to Olaf but keeps him on a long leash, following him from a safe distance until the man has passed the last Svartdalen houses and disappears in the grove.

It doesn't take "Kurtz" long to spot Olaf again, even though, meanwhile, the Norwegian has strayed quite a bit from the beaten path to get to the fjord's banks. In his present position, a hillock overgrown with moss and lichen shields "Olaf" from the through traffic on the road, at the same time blocking his view of everyone approaching him from that side.

He has taken off his sneakers and lets his feet dangle in the icy water while he files through a notebook of sorts. Its tattered pages indicate that the scrapbook must have accompanied him for quite some time already. Nor is this likely to be his first visit to this spot. Presumably, there have been other hot dates of the sort he is looking forward to now. Smultronstället, the secret place where the wild strawberries grow. That's what the neighbouring Swedes call a place like that. A small retreat, only known to few, a tiny little speck of Eden God allows some of us particularly well behaved to retain after the disappointing Fall from Grace, in general.

With a limp that seems to grow more perceptible by the minute, "Kurtz" now leaves the beaten path as well and, looking cagily left and right, stalks through the shrubbery towards the moss-covered hillock. Apparently, he wants to surprise "Olaf", who may not be expecting him, at least not at this time of day. As skilfully as "Kurtz" winds his way through the grove despite his handicap, he might fool even an experienced hunter or park ranger. As for "Olaf", having plunged deeply into his scrapbook, biting off a piece of the apple he took out of his bag, all he probably hears is the lapping of the curling wavelets and the rushing by of the odd motor home.

When "Kurtz" has come close enough for his purposes, he grabs under the seams of his pullover behind his back and pulls out a snub-barrelled revolver so small it almost disappears in his fist. The gun in his right hand, he pops the barrel and rotates it with the palm of his left to make sure there's a fresh round in each chamber except the first one. The purring metallic sound and the snapping of the cock have at last alerted "Olaf", who turns his head nervously and lowers his booklet. "Kurtz" is now only a few steps away from him, as he raises his gun to the height of "Olaf "s head.

"Olaf Bergström?" he asks in the same dry, matter-of-fact voice with which a pizza-deliverer might ascertain he's found the right customer.

"Olaf" doesn't reply. He drops his notebook, jumps off the rock and makes a move towards the road. But, all things considered, that's a hopeless gesture. With a quick swerve of his gun, "Kurtz" follows the movement of his victim and fires a single shot. One shot, only. The bullet hits "Olaf" in the left temple and jerks him a step or two to the right, where he collapses and lies motionless. Blood is colouring his thick blond hair red in places like poppy growing from a field of golden rape.

"Kurtz" has to be sure of himself in more ways than one. He hasn't bothered to use a silencer, yet the relatively small calibre of what might have passed as a toy gun emits but a discrete bang. And even in the unlikely case of someone's attention having been caught by the sound, there are so many elk hunters on the loose in these parts, a solitary shot like this one scandalizes no-one.

Neither does "Kurtz" verify whether or not his victim is really stone cold dead. Instead, he pockets his gun, picks up "Olaf"'s scrapbook and, shaking his head at so much self-indulgence, drops it next to the body as if trying to make sure the blond effigy of a Viking has enough material to read while travelling to Walhalla. No traces to obliterate – there aren't any except maybe his footprints. A veteran Indian scout in the redneck backwoods of Arizona might well be able to identify the killer as a man with a limp. The Norwegian police, however, are unlikely to employ any offspring of Cochise or Geronimo. And so, with measured steps, he walks back towards Svartdalen and his fully air-conditioned Cherokee bronco.

3. Islands in the Stream

The man in the cockpit of his elderly little Westerly sailing yacht with its patriotic blue and red stripes around what must once have been an immaculately white hull lets go of the steering wheel for a moment to sip some hot tea from a Thermos which he secures in a wooden rack on the boat's steering column. The yacht is coming from the general direction of St. Peter Port, Guernsey, whose Victoria Marina it probably left an hour or so ago.

Because of their strong currents and innumerable rocks lurking above or just below the surface, the waters east of Guernsey are considered hazardous even by the locals. Yet the man in the Westerly either knows his way about or calmly places his fate in the hands of the Lord. Pleading in favour of a certain basic familiarity with the difficult local conditions is the fact that he happens to have chosen the best moment for this part of his voyage and doesn't seem to be acting with any noticeable frantic activity or unnecessary precipitation. By the look of it, he isn't particularly impressed by the region's bad karma at all.

Keeping the setting sun at his back, he profits from its warm, soft rays spreading almost horizontally, so that the man's vision is not impaired by any irritating jack-o'-lantern reflections on the restlessly billowing surface of the sea. That's a good thing, since the best possible visibility is a vital prerequisite when aiming at threading the eye of the needle between the islet of Jethou and the mere rock of Crevichon, a passage the Westerly's skipper seems ambitious enough to tackle. Excellent visibility comes as a godsend in an area like this, frequently haunted by fog and mist. While there is precious little a man can do about the weather conditions of the day, most recent large-scale charts as well as thoroughly updated tide tables are indispensable requirements any responsible skipper should see to having aboard at all times. As today's tidal data show, the rickety old Westerly is right on the money, sailing on a rising tide at halfway house.

As the saying goes, time and tide wait for no man. To ascertain the truthfulness of the former, an occasional hard look in the mirror will do. For anyone wishing to check on the veracity of the adage's latter part, the Bay of St. Malo, reaching from the spiked helmet of Mont St. Michel in the South to Cap de la Hague in the North would make a first-rate testing ground.

This is chiefly due to the topographical characteristics of this arrowhead of a gulf marking the borderline between Normandy in the East and Brittany in the West. Every time huge masses of Atlantic water are pushed north-northeast by the tide, they have no other option but to hit the natural barrier of the Cotentin peninsula, functioning like a dam in those situations. The resulting mean tidal amplitude, viz. the difference between mean high and low water marks as registered over a long period of time, reaches impressive forty-foot peaks.