Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Landauer

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

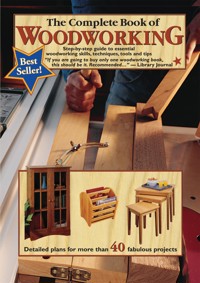

The Complete Book of Woodworking is a comprehensive guide to help you become a master woodworker and have a house full of hand-made furnishings to show for the effort! Set up shop, understand the tools, learn the principles of basic design, and practice essential woodworking techniques as you complete 40 detailed plans for home accessories, furnishings, outdoor projects, workshop projects, and more! With over 1,200 full-color photographs, step-by-step instructions and illustrations, and helpful diagrams, woodworkers of all levels will enjoy enhancing their skills and learning something new!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 718

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Complete Book of

WOODWORKING

Copyright © 2001 North American Affinity Clubs

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Published by Landauer Publishing, LLC

3100 100th Street, Suite A, Urbandale, IA 50322 1/800-557-2144

Produced in cooperation with Publishing Solutions, LLCJames L. Knapp, President

Credits

Tom Carpenter, Director of Book Development

Mark Johanson, Book Products Development Manager, Editor

Dan Cary, Photo Production Coordinator

Chris Marshall, Editorial Coordinator

Steve Anderson, Senior Editorial Assistant

Bill Nelson, Series Design, Art Direction & Production

Mark Macemon, Lead Photographer

Ralph Karlen, Photography

Kim Bailey, Tad Saddoris, Contributing Photographers

Bruce Kieffer, Illustrator

Craig Claeys, Contributing Illustrator

Brad Classon, John Nadeau, Production Assistants

Michele Teigen, Book Development Coordinator

Shelton Design Studios, Cover Designer

Print ISBN: 978-0-9800688-7-0eISBN: 978-1-6076575-9-0

Landauer Books are distributed to the Trade by

Fox Chapel Publishing

1970 Broad Street

East Petersburg, PA 17520

www.foxchapelpublishing.com

1-800-457-9112

For consumer orders:

Landauer Publishing, LLC

3100 100th Street

Urbandale, Iowa 50322

www.landauerpub.com

1-800-557-2144

Introduction

For anyone with creative instincts and a joy for working with your hands, woodworking can be a very rewarding hobby, perhaps even a lifelong passion. It’s more than just a way to turn wood products into furnishings and accessories for your home. It is exercise for your compulsion to be productive. It is a refuge from the stresses of life. It is an art form that yields beautiful objects to make life more pleasant for you and your loved ones. It is an opportunity to experience the pride and satisfaction that can only come from making something yourself.

Once you’ve started down the woodworking path, you’ll find there are many directions you can take. You may enjoy making fine furniture, or perhaps toys and gifts that you can pass along to others. You may be attracted to the design process and spend most of your shop time at the drafting table, dreaming and sketching. Or you may succumb to the lure of the workshop—for many of us, the real pleasure of woodworking is in setting up our own private spot in the world and whiling away the hours simply puttering. The choices are virtually unlimited.

The Complete Book of Woodworking is both an indispensible reference volume and a source of inspiration. In the first section, you’ll find fully photographed, step-by-step instructions that show you precisely how to accomplish all of the most essential woodworking skills. Whether you’re a beginner or an old hand in the shop, you’ll find a wealth of tips and techniques that will make you a better woodworker.

The first chapter, Setting Up Shop, provides a useful glimpse into how seasoned woodworkers go about creating and furnishing their workshops. Designing Woodworking Projects walks you through the entire process of developing a raw idea into a complete woodworking project plan. Introduction to Wood explains the mysteries of wood and offers practical advice on selecting the species that’s right for your project, as well as some inside information that will help you find your way around the lumberyard. The fourth chapter, Squaring, Marking & Cutting Stock, is a comprehensive guide that shows you how to prepare your rough wood, make layout lines and cut your project parts to size and shape. It also provides a solid introduction to the basic woodworking tools you’ll use to machine wood stock.

Making Joints & Assembling Projects discusses the best wood joinery options and techniques, as well as essential clamping and gluing skills. Finally, in Applying Finishes, you’ll receive a crash course in prepping, staining and topcoating wood.

But The Complete Book of Woodworking is more than just a comprehensive reference book for woodworkers. After all, what fun is it to learn new skills if you have nothing to do with them?

Toward that end, we have included plans, measured drawings, cutting lists, instructions and photographs for 40 original woodworking projects you can build to put your new skills to the test. Covering a range of skill levels, from beginner to advanced, the projects create an irresistible menu of furnishings and accessories. No matter what your tastes or needs, you’re sure to find just the item you’ve always wanted to make.

Home Accessories includes plans for a wide variety of clever projects that will make your home more attractive, more functional and truly your own. Included are a beautiful mission-style coat tree, a country-style wall-hung cupboard, benches, boxes, picture frames and more. Home Furnishings features plans for bookcases, bigger benches, a dresser, a gorgeous rocking chair, and a couple of tables. All the projects are unique, buildable and beautiful.

Outdoor Projects takes you into perhaps the most popular woodworking area these days. A stunning array of projects for outdoor seating, dining and leisure will dress up any yard or deck. Most are built with dimension lumber and simple joints, making them perfect for the beginner. But you’ll find a few eye-poppers that will challenge your skills, as well! Finally, Workshop Projects provides plans for a half-dozen helpful furnishing and accessories to make your workshop more functional and pleasant, including a pair of clever workbenches.

Because it is both a thorough guide to woodworking skills and a treasure-trove of terrific woodworking project plans, we think you’ll understand why we say The Complete Book of Woodworking is truly complete.

IMPORTANT NOTICE

For your safety, caution and good judgement should be used when following instructions described in this book. Take into consideration your level of skill and the safety pre-cautions related to the tools and materials shown. Neither the publisher nor any of its affiliates can assume responsibility for any damage to property or persons as a result of the misuse of the information provided. Consult your local building department for infor-mation on permits, codes, regulations and laws which may apply to your project.

Table of Contents

Setting Up Shop

Choosing Your Space

Power & Lighting

Ventilation, Dust Collection & Climate Control

Workshop Furnishings

Workpiece Support

Shop Safety

Designing Woodworking Projects

The Woodworking Project Design Process

The Essentials of Style

Making Prototypes

Making Plan Drawings

Introduction to Wood

Anatomy of a Tree

Defining Hardwoods & Softwoods

Cuts of Lumber

Methods of Drying Lumber

Moisture & Wood Movement

Lumber Distortion & Defects

Softwood Lumber Sizes

Hardwood Lumber Sizes

Buying Lumber

Sheet Goods

Common Hardwoods

Common Softwoods

Sampling of Exotics

Squaring, Marking & Cutting Stock

Squaring Stock

Laying Out Parts

Marking Curves & Circles

Making & Using Patterns

Cutting Project Parts

Making Rip Cuts

Making Cross Cuts

Making Angled Cuts

Making Curved Cuts

Template Routing

Shaping Profiles

Resawing Lumber

Tips for Minimizing Tearout

Making Joints & Assembling Projects

Casework Joints

Furnituremaking Joints

Laying Out & Cutting Joints

Butt Joints

Biscuit-Reinforced Butt Joints

Dowel-Reinforced Butt Joints

Dado & Rabbet joints

Tongue & Groove Joints

Mortise & Tenon Joints

Lap Joints

Finger Joints

Hand-Cut Dovetail Joints

Half-Blind Dovetail Joints

Woodworking Glue Options

Useful Woodworking Clamps

Working with Clamps

Assembling Projects

Applying Finishes

Smoothing Wood Surfaces

Applying Wood Stains

Filling Wood Pores

Choosing Finishes

Applying Finish Topcoats

Glossary

PROJECTS

Home Accessories

Mantel Clock

Arts & Crafts Bookstand

Firewood Box

Country Wall Cabinet

Tavern Mirror

Over-Sink Cutting Board

Two-Step Stool

Magazine Rack

Coat Tree

Tambour Breadbox

Lapped Picture Frames

Mini Treasure Chest

Home Furnishings

Five-Board Bench

Basic Bookcase

Tile-Top Coffee Table

Changing Table/Dresser

Entry Bench

Nesting Tables

Formal Bookcase

Walnut Writing Desk & Console

Arts & Crafts Bookcase

Corner Cupboard

Mission Rocker

Outdoor Projects

Patio Tea Table

Cedar Birdhouse

Basic Garden Bench

Formal Garden Bench

Patio Table & Chairs

Tile-Top Barbecue Center

Kid-Size Picnic Table

Frame-Style Sandbox

Adirondack Chair

Sun Lounger

Porch Swing

Picnic Table & Benches

Workshop Projects

Sawhorses

2 x 4 Workbench

Sheet Goods Cart

Wall-Hung Utility Cabinet

Woodworking Workbench

Setting Up Shop

Designing Woodworking Projects

Introduction to Wood

Squaring, Marking & Cutting Stock

Making Joints & Assembling Projects

Applying Finishes

Home Accessories

Home Furnishings

Outdoor Projects

Workshop Projects

Setting Up Shop

A workshop is a defined space that, together with everything contained in it, provides the means to explore your woodworking hobby. Even if you’re still at the stage where you’re only thinking about learning the craft of woodworking, you probably have a space in mind already, along with some ideas about how you could customize it and furnish it to meet your needs.

A “Dream Shop” like this is fun to think about but not really a viable option for most of us. Still, by making smart tool-buying choices and using limited space efficiently, you can turn your own modest shop space into a hardworking part of your home that provides a pleasant place to retreat.

Woodworking virtually demands its own space. The necessary power tools are fairly big. The materials, too, are bulky. And with each project you undertake you’ll undoubtedly have a few wood scraps or pieces of hardware left over that you can’t bear to throw away. And since most projects are completed over a period of days, weeks, months or even years, they’ll need a place to reside. Also consider others: woodworking in action isn’t always neighborly—the tools are generally noisy and they generate a lot of dust, which can be a real nuisance to those who share your home. Confining the mess and noise to a dedicated area will make everyone happier.

There is no “correct” order to follow when setting up or rehabbing your workshop space. Certainly, it’s always good advice to think and plan a bit before you start knocking out walls, running new wiring circuits or maxing out your credit cards at the tool store. But don’t get so hung up in the planning and dreaming phase that your workshop never comes into being. Take a few chances, see what works out well for you and your family and what does not. Experiment as you plan. And don’t forget that the more pleas-ant and comfortable your shop environment, the more likely it is that you’ll spend time in it—and the more likely you’ll be to finish the projects you start.

The more pleasant and comfortable your shop environment, the more likely it is that you’ll spend time in it.

Choosing Your Space

Without a doubt, the best shop is a large, separate building, with plumbing and heat. It is divided up to include a storage area adjoining a large door to the outside, a central workspace, and a finishing room that’s walled off from the rest of the shop and ventilated to the outdoors. Obviously, establishing and maintaining such a shop requires money and space that most of us don’t have available. So look for realistic alternatives.

The two most common shop locations are the basement and the garage. Shops have been set up in spare rooms, attics, even in closed-in porches. When assessing potential shop areas, or considering upgrading or remodeling your current shop, keep the following factors in mind:

Space needs. You’ll want to have enough space to maneuver full-size sheet goods and boards that are eight feet or longer. Ideally, this means a large enough area that you can feed large stock into a stationary tool with enough clearance on the infeed and the outfeed side.

Access. You’ll need a convenient entry/exit point so you can carry materials into the shop and completed projects out of the shop.

Power. You should never run more than one tool at a time (except a tool and a shop vac or dust collector). Nevertheless, you’ll need several accessible outlets.

Light. Adequate light is essential for doing careful, comfortable, accurate and safe work. You’ll need good overall light (a combination of natural and artificial light sources is best) as well some movable task lighting.

Ventilation/climate control. To help exhaust dust and fumes, you need a source of fresh air and dust collection. Depending on where you live, year-round shop use likely will require a means of heating and/or cooling the shop as well as controlling humidity.

Isolation. Keep the inevitable intrusions of noise and dirt into the rest of the home to a minimum.

The Basement Shop

The basement offers many advantages as a shop location. It’s accessible yet set off from the rest of the house, and the essential house systems are right there. Drawbacks tend to be limited headroom, negligible natural light, concrete floors and overall dampness/poor ventilation.

The Garage Shop

The garage, especially one attached to the house, offers the convenience of a basement shop with fewer drawbacks. Overhead doors provide excellent access, greater headroom, lower humidity and better ventilation. The main general drawback is that garages are usually home to one or more vehicles and a host of other outdoor items. A good solution is to mount your stationary tools on casters so they can be wheeled out of the way to make room for other things.

TIPSFORSUPPLYINGPOWER & LIGHT

Mount a power strip to the base of your workbench, assembly table or workstation where you’ll be using more than one power tool. Retractable extension cords provide an additional power supply and can be hung from the ceiling to stay out of your way when not in use.

An articulated desk lamp provides focused task lighting that’s easy to move wherever it’s needed in your shop. Incandescent lighting is the best choice for task lights that are used frequently.

Calculate your power load

A tool’s power requirements should be listed on a plate on the motor housing.Add up the total wattage (amperage times voltage) of each tool and light on a circuit. Note: Use the wattage listed on incandescent bulbs. The wattage requirements for fluorescents needs to be increased 20% to account for the lamp ballast load. Generally, the maximum load for a 15-amp circuit using either 14-gauge or 12-gauge wire should be under 1,500 watts. A 20-amp, 12-gauge circuit should not carry more than 2,000 watts of load. Include every item in the circuit that draws power, whether you plan to run them at the same time or not. If your total wattage exceeds the ratings of the circuit supplying your shop, add an additional circuit or two.

Power & Lighting

Nearly every potential shop space will need electrical improvements. You may not need to go to pro-shop extremes, where each tool has a dedicated circuit. But avoid putting larger stationary tools (especially dust collectors) on a shared circuit. Since many larger stationary tools run on 230-volt service, it’s not a bad idea to run a 230-volt circuit for future use if you’re already updating the wiring.

There is a limit to the number of receptacles or fixtures you can hang on a circuit. A good rule of thumb is 8 to 10 lights or outlets per circuit. Rules and regulations are outlined in the National Electrical Code (NEC), but you should also consult your local city or county codes. Unless you have experience wiring, hire a licensed electrician for the job.

The best lighting for the shop is a balance of natural and artificial light and a balance of overall light and task light. Unfortunately, natural light is often hard to come by; many shops simply don’t have windows. One way to compensate for poor lighting is simply to do some basic cleanup and some painting with a light color. The walls and ceiling are the primary reflective surfaces, but a floor covered with light-colored enamel paint or vinyl tile will also make a big difference.

At minimum, you should have 20 foot-candles of lighting at floor level, throughout the shop: figure on providing at least one-half watt of fluorescent light or 2 watts of incandescent light for each square foot of shop floor (fluorescent lights are four to six times more efficient than incandescent and cast more uniform, shadow-free light). You’ll also need task lighting.

Wiring tips

∎ Separate lighting circuits from receptacle circuits. If you trip a breaker with a power tool, you don’t want to be left in the dark.

∎ Provide full power to a centrally located workbench through a floor-mounted receptacle or via a retractable cord suspended from the ceiling.

∎ Alternate the circuits from receptacle to receptacle. Or, wire each outlet of a duplex receptacle to a different circuit. That way, if you plug a power tool into one outlet and a shop vac into the other, then run both simultaneously, you’ll be drawing power from two circuits, rather than one.

∎ Ground-fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs) are required in garages, unfinished basements, outdoors, and locations near water.

An elaborate dust collection system is the hallmark of a serious woodworker. In this shop, each stationary tool has a dedicated hose and port that tie into the central vacuum ductwork.

Ventilation, Dust Collection & Climate Control

Ventilation. In any shop, ventilation can be problematic. The air fills with fine sawdust particles or finishing fumes very quickly. Airflow—all it takes is a window or attic fan—can clear the air, but if it carries the dust and stink into the living areas, or pulls cold air into the heated space, it isn’t a remedy. An ambient air filtration system that circulates air though filters may be your best solution.

Dust collection. Accumulating sawdust is the bane of the woodworker. It conceals cutting lines, plugs up tools and presents several dangers to your safety. That’s why setting up a system to remove as much sawdust as possible at the source is so critical.

Climate control. Heating a shop is important not simply for your personal comfort. Some woodworking operations—gluing and finishing are examples—are sensitive to temperature. A wide range of heating systems are available: central systems, radiant panels, in-wall space heaters, and portable space heaters fueled by wood, oil, gas, propane, kerosene, and electric, even coal and pellets. Avoid open-coil electric heaters, kerosene heaters, and open-flame heaters of any sort, because they can ignite sawdust, wood shavings, or flammable finishes in a shop. Use dehumidifiers and humidifiers to control shop humidity.

A humidity gauge lets you monitor the humidity level in your shop so you can run humidifiers and dehumidifiers as needed to keep the humidity constant for the duration of your project. Where possible, try to achieve a base humidity level that is roughly the same as the average humidity in the room where the project will end up.

Dust collection/air filtration devices improve air quality in the shop. Single-stage dust collectors attach to stationary power tools through a system of flexible ductwork. A motor-driven impeller draws air through the ductwork and into replaceable collection bags. Ambient air cleaners are fitted with filters to trap fine, airborne dust that can elude other dust collectors. Both portable and ceiling-mounted styles are available. A shop vacuum is handy for spot-cleaning but not designed to be the heart of a dust-collection system.

Workshop Furnishings

A shop needs flat sturdy worksurfaces and plenty of storage. Both of these needs are filled by your workshop furnishings.

Workbench. A first-class bench can be expensive, but you don’t need anything elaborate. A low-cost handy-man’s bench from the local home center may actually be better for your needs. You can also build your own. Simple workbenches aren’t difficult to make, and you’ll end up with exactly what you need. You can even speed things up a bit by using some prefabricated materials, like cabinets and countertops. Bench dimensions vary by intended use, but a good all-purpose bench size is 34 in. high, 30 in. wide, and 60 in. long.

Regardless of the design of your workbench, you want it to be heavy and rigid. The starting point is the leg assembly. A commercial joiner’s bench usually has a trestle-type base assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints. It will be made of hard maple or beech, maybe oak. But a massive, rigid structure can be built with nothing more exotic than 2 x 4s, glue, and drywall screws. The resulting bench may not look as handsome as a commercial unit, but it will be heavy and very strong. The time-honored way to beef up a bench is with a thick top. Manageable ways of getting a good top include buying a length of butcher-block countertop, face-gluing lengths of well-dried Douglas fir 2 x 4s, and layering several pieces of plywood, particleboard, or medium density fiberboard (MDF). Two or three coats of penetrating oil, such as tung oil or Danish oil, is the best finish for a benchtop. Never stain or paint a benchtop; the color can mar workpieces.

Vises & bench dogs. Strong and easy to operate, a bench vise is all metal, including the jaws (add wood facings to the jaws to protect your work). A sliding dog in the movable jaw, used in conjunction with a dog in the benchtop, comes in handy for clamping work on the bench surface. One great feature is the quick-action lever, which allows the front jaw to be moved without all the tedious cranking.

WORKBENCHOPTIONS

A woodworker’s workbench (purchased or shop-built) with one or two woodworking vises, bench dogs and a heavy-duty hardwood benchtop is the centerpiece of a wood shop.

A rugged set-up table made from dimension lumber and sheet goods is economical, easy to make and can accommodate most woodworking functions.

Kitchen cabinets work well in a shop. Find inexpensive or used base cabinets and attach a countertop to create a worksurface that can also be used for short term storage or a workstation.

Lumber storage

Exposed wall framing members (or ceiling joists) in garages or basements can be converted to out-of-the-way storage spots for lumber simply by attaching a scrap wood rail that spans the framing members and holds the boards in place.

A typical lumber rack is constructed from inexpensive dimension lumber. It should contain several racks for storing lumber flat, as well as a vertical cubby for storing full-size sheet good panels on-edge. The vertical supports should be tied into both the floor and the ceiling.

Mount at least one vise on your bench, bolting it to the underside of the benchtop, so the top edges of the jaws are flush with the bench’s top surface. Bench dogs expand the utility of your vise. Locate a row of dog holes in line with the pop-up dog on your vise. Position them about 4 in. apart.

Workbench storage. Storage can be organized under the workbench. Most straightforward is a simple shelf for tools and supplies. A built-in cabinet, with drawers and doors, does a better job of organizing the space and keeping things clean, but it blocks access to the benchtop for clamping purposes. The best compromise is a cabinet installed between the bench legs, 8 in. or so below the benchtop.

Storage furnishings. Wood-working involves a vast array of tools, equipment, accessories, supplies, and materials that make well-designed storage essential. The photos on these two pages will give you some good ideas for coping with clutter.

A rolling lumber cart makes transporting stock to the work area more convenient, but its best feature is that you can move it out of the way as needed to free up working space in a small workshop.

Shop layout tips

The centerpiece of your shop should be your workbench. Position the bench so you have access to at least two (and ideally four) sides. Where floor space is at a premium, place the bench at the outfeed end of the table saw. That way, you can forego a separate outfeed table and allow the bench to do double duty.

Place your cross-cutting saw below a wall-mounted lumber rack to minimize handling full-length lumber as much as possible. Fixed extension tables with fences on each side of this saw make cross-cutting fast, easy and safe. On the wall opposite your cross-cut station, locate storage for tools, supplies, and hardware. Build a floor to ceiling unit, making it no deeper than what’s necessary to house your largest portable/benchtop tool. Store benchtop tools at benchtop height, so you don’t have to stoop and lift all the weight.

Perforated hardboard (pegboard) is a trademark of the organized workshop. In addition to general pegboard hooks, you can purchase whole systems of hanging devices in many sizes and configurations. Use tempered hardboard and set it into a sturdy frame to create clearance for the hook ends behind the pegboard.

A locking cabinet is a good idea for storing your valuable hand tools and portable power tools. More than security against theft, it keeps them from being used by kids or unauthorized people. You can make a basic cabinet yourself from just a couple of sheets of plywood. For maximum efficiency, measure the height and depth of your tools first and dimension the cabinet with a suitable space in mind for each tool.

Wall-mounted clamp racks protect your clamps and keep them organized and accessible. A few lengths of scrap lumber and some ingenuity are all it takes to devise your own clamp storage system. Cut notches to hold heavier bar and pipe clamps. Smaller clamps can simply be tightened onto your rack or hung from a cord.

A roll-around cabinet, like this mechanic’s parts cabinet, is a great shop furnishing for storing hand tools, saw blades, drill bits, hardware and other small tools that need to be kept organized. By rolling the cabinet to your work area, you’ll save a lot of trips back and forth across your shop retrieving tools or putting them away again.

A rolling scrap bin is handy in shops of all sizes, and can even double as an outfeed “table” if the rim of the bin is set to the proper height. Use the bin to store cutoff pieces while a project is in progress. Then, once the project is built, sort through the leftover pieces and save or discard them as you see fit. You might consider painting the bin to avoid confusing it with your trash can.

A metal cabinet with tight-closing, locking doors is not only a good idea for storing finishing materials and chemicals, it’s also required by most fire codes for commercial workshops. Used office furnishing stores are great places to look for metal cabinets like the one shown here. Paint a clearly visible warning on the cabinet doors.

Workpiece Support

Furnish your shop with a number of convenient (and preferably portable) work supports. Adequate workpiece support is critical to making accurate, safe cuts. Most woodworkers have several different types of work supports in their shop, from manufactured, adjustable outfeed supports to saw table extensions. A few sturdy pairs of sawhorses will also come in handy. And you can use rolling caster bases for your benches or other stationary tools to set the top surfaces at a uniform height.

A power miter saw workstation with auxiliary tables and fences lets you support and cut longer stock without having to set up additional supporting devices first. Keeping your portable tools in one spot as much as possible also prevents them from falling out of square as readily.

Make room for sawing. Allow 4 ft. of clear space on each side of a table saw and 8 to 10 ft. in front and in back so you’ll have plenty of room to work. Be sure to have adequate outfeed support in place when cutting larger stock.

“Sturdy” and “movable” are the two most important characteristics of good work support. Casters can make just about any shop furnishing into a useful work support (photo above). And you can never have too many sawhorses or portable workstations (above photo).

Tips for setting up & equipping a safe workshop

Protect hearingwith ear muffs (A) expandable foam earplugs (B) or corded ear inserts (C).

Protect against dust & fumes.A particle mask (A) is for general work. A dust mask (B) has replaceable filters. A respirator (C) can be fitted with filters and cartridges.

Protect eyes.A face shield (A) is for very hazardous work. Safety goggles (B) and glasses (C) with shatterproof lenses are for general cutting and shop work.

Create an emergency areaThe workshop is perhaps the most accident-prone area of your home. Sharp blades, heavy objects, dangerous chemicals and flammable materials are just a few of the factors that increase the risk of accidents in the shop. While good housekeeping, respect for your tools and common sense will go a long way toward reducing the risk of accidents, you should still be prepared in the event an accident occurs. Designate part of your shop as an emergency center. Equip it with a fully stocked first aid kit, fire extinguisher and telephone with emergency numbers clearly posted.

A first aid kitshould contain (as a minimum) plenty of gauze and bandages, antiseptic first aid ointment, latex gloves, a cold compress, rubbing alcohol swabs, a general disinfectant such as iodine and a first aid guidebook.

Stay alertA lapse in concentration brought on by physical or mental fatigue is responsible for most shop accidents. A few simple precautions, like setting a cushioned floor mat at your workstations, can help reduce physical fatigue. Take plenty of breaks to stay mentally alert and never work with tools if you’ve consumed drugs or alcohol.

Designing Woodworking Projects

Decisions, decisions, decisions. That’s what designing a project is all about. Whether you use an existing project plan, modify an existing plan, or develop your own plan, completing a design process is a necessary and rewarding first step before you ever start to build your project.

Most people think of project design as merely deciding the appearance, or the “look” of the finished piece, but there’s much more to it than that. It’s a process that takes you through all the aspects of developing your best ideas, then figuring out the best way to give those ideas form in the shape of a woodworking project. It also helps you plan thoroughly so your project will function as intended. When you’re done with the design process, no decisions should be left unmade.

Essentially, you build your project using drawings, prototypes, and a lot of forethought prior to the construction stage. Think the plan through completely. It is possible to work out some details during the construction, but it’s much better to anticipate and solve those problems in advance, rather than backtracking during the construction and even remaking part of what you’ve already built.

As you work your way through the design process, you’ll want to consider goals such as: creating a piece with an overall appealing look that also fits well in its surroundings; making your style, proportions, wood, moldings and details, hardware, and finish choices all blend together; and making sure your piece will work. If it’s a chair, will it be comfortable? If it’s a storage cabinet, will the items fit well in the space you provide? You’ll also want to consider the tools and construction techniques needed to create your project, and what different ways there may be to achieve similar results better and more efficiently.

Project design may seem like a daunting process, but it doesn’t need to be. In fact, most woodworkers feel that the contrary is true. The more involved and familiar you become with the design process, the more rewarding and easier it and your construction process will become. While you don’t necessarily need to follow the steps of the design process in the order given in the pages that follow, you do need to follow them in some manner. You’ll probably find that you jump from step to step and go back and forth a bit. This is fine as long as you do it all, and do it thoroughly. Get in the habit of using the fundamentals of design, and your finished projects will be much more satisfying and definitely much better accomplished.

Project design is a process thattakes you through all the aspects of developing your best ideas then figuring out the best way to give those ideas formin the shape of a woodworking project.

This chapter will guide you through the design process so you can make better design decisions. The process will show you how to analyze your options, and it will explain the reasons why you might choose one option over another. The end results should help ensure that you design a solid project you’ll be happy with. The last part of this chapter will explain different types of drawings you can make to help you visualize your ideas, as well as a section about the process of building prototypes to help you work out your design details quickly and three-dimensionally.

WOODWORKING WORKS A successful woodworking project starts with a well-planned design. You can base your plan on a familiar furnishing, like the Mission-style rocker to the right, or come up with something completely new and completely yours, like the play table and chairs on the left.

What should I build?

Deciding what to build is the point where the design process seems to always begin.

Most often, the desire to build something comes from a specific need: Maybe the need is to replace an old, worn out piece of furniture, or to build a piece of furniture to supplement the furnishings you already have. Perhaps you need an entertainment center to organize and store your audio and video equipment and accessories, or a bookcase to hold all of your books. Maybe your goal is as simple as the desire to build something. Or perhaps you want to challenge your woodworking skills by trying something different or learning something new. Sometimes even the desire to make something in a style you haven’t worked in before is reason enough to get you started.

I recently built myself a new desk. My old desk got too small for all the things I wanted close at hand and the desktop was jammed with computer equipment, leaving me no room to work comfortably. My office was large enough to handle a much bigger desk. So there I was: I had a need to fill and I decided to design and build a new desk for myself. And it turned out great—mostly because I spent a lot of time with the design process.

Deciding what to build is probably the easiest part of the design process. All it takes is a little imagination and some planning. And remember that a healthy desire to explore new techniques is what makes woodworking a hobby, not a chore.

~Bruce Kieffer

The Woodworking Project Design Process

The woodworking project design process starts with a simple idea, sometimes based on a specific need. The raw idea is tossed around, mulled over and compared to other ideas, existing furnishings and design styles. Gradually, a rough concept takes shape, usually in the form of a sketch. The concept is tested by making more sketches or models and simple prototypes. The bugs are worked out. Finally, it is put down on paper in a measured, dimensioned form, along with cutting lists, shopping lists and details of some of the joinery. The end result is a hard plan that becomes the road map to building your woodworking project.

Generating project ideas

There is no single best way to come up with good ideas for woodworking projects. But there are a few places you can look to help you refine a basic concept. One of them is actual pieces of furniture, whether they’re in your home, a friend’s home, or a furniture store. Seeing living, breathing woodworking projects and home furnishings will give you an opportunity to scrutinize different designs and styles up close; to get an idea how the parts fit together; to analyze the small details, as well as the overall proportions; and to evaluate how well different pieces of furniture function.

Another good way to generate and refine your ideas is simply to discuss them with fellow woodworking enthusiasts. They’re usually not hard to find and are more than happy to chat about their favorite pastime with anyone who will listen (See tip box, next page).

The local library or your own collection of books and magazines can be excellent sources to help you put a face on the project you’ve been imagining. You may even encounter a completed set of project plans that meets your needs to a tee. Many woodworking project plans include drawings, cutting lists, shopping lists, how-to instructions and photographs. And if what you find is close, but not exactly what you need, most likely you can modify it to suit your needs. You can save a lot of design time by using an existing plan. Just make sure to work out in advance those aspects of the published plan that are new to you.

Evolution of a woodworking project

1Create the design. This step is not as simple as it sounds, but for many woodworkers it is perhaps the most gratifying, if not fun, stages of the process. In it, you’ll move f rom a raw idea to a hard plan.

2Build a prototype. Not everyone chooses to test their plan by building a scale model or a simple prototype, but it is the best way to catch errors and make improvements before you start. Prototyping often takes place before the hard plan is finished.

3Build the project. The more time you spend in the design phase, the more smoothly the actual construction of your project will go. You may still end up doing a little bit of “designing on the fly,” but the chances of a major catastrophe are greatly reduced if the plan is solid.

Antique stores, salvage yards and furniture stores are rich with possibilities for generating ideas. Explore them. Pay attention to shapes and proportions and even joinery techniques. If you see something you like, chances are you can come up with a way to make one for yourself.

Even watching television and movies can be a productive way to generate some good ideas. This may sound a little strange, but most professional woodworkers and designers are on constant lookout for new ideas. Television and movie stylists tend to put a lot of time and effort into choosing their props, and they pay attention to style and design trends.

In reality, the things that can influence you and help you generate ideas are everywhere—you just need to look closely and you will see them.

Creating a concept sketch. Once you have a rough idea of the project in mind, it’s time to get it down on paper. The initial drawings, called “concept sketches,” don’t need to be fancy or even drawn to scale. But getting them down on paper is the trigger to refining the design—it’s also a good idea to have a representation of the idea that you can hold onto, since none of our memories are what they used to be.

As you sketch and doodle, start thinking about some of the more concrete design issues: Is there a particular style you favor (See here to here)? Exactly how big do you want it to be? What should the proportions be (See here to here). In short, play around with ways the project might look until you find one you like.

Share ideas with other woodworkers

One of the best sources for project ideas is other woodworkers. As a group, woodworkers love to talk about woodworking. You probably already know a lot of other woodworkers, but if not, they’re easy to find. Look in the phone book to find local professional woodworkers. But don’t just pop in on the professionals. Be considerate, call and ask if they would be willing to spend a little time guiding you. Phrased that way you’re more likely to get advice.

You can also find woodworkers at a local woodworking club or guild. Woodworking guilds can be professional, amateur, or a combination of both. Most of the members are amateur woodworkers who joined to learn more about woodworking by attending our monthly educational meetings. You could also visit your local woodworking supply stores and see who you run into. Woodworkers are all over those places, and most of them are very eager to talk shop and give out a few of their opinions.

At a typical woodworker’s guild meeting, like this one in Minnesota, one of the members or a special guest will give a demonstration on a new or favorite technique.

Practical considerations. Once you’ve got a fairly detailed concept sketch in hand, and a pretty good idea of where you’re headed with the project, turn your attention to some of the more practical details.

One of the first “practical” decisions you’ll need to make, other than the approximate size and scale, is which wood species to use. In most cases, the furniture style you choose will dictate the best wood species to use. If your goal is to reproduce a style accurately, then not just any wood will do. For example; Mission-style pieces were almost all built using quartersawn white oak. Not only would it be a shame to build a Mission-style piece using, say, knotty pine, it probably wouldn’t look right. In the same respect, building a country-styled piece using teak would be a questionable choice. It isn’t unheard of for professional designers to throw an odd species or two into a more traditional plan for effect, but more likely than not you’ll be disappointed with the outcome if you try it.

As much as (if not more than) style, function and budget will bear on your wood species selection. Outdoor furniture, for example, must be made using rot-resistant lumber or it won’t hold up to the weather. Unless you’re willing to shell out the money for teak or mahogany, that leaves white oak, redwood, cedar and cypress as the main options (excluding pressure-treated pine, which is perfectly suitable for projects that are not “fine woodworking”). By the same token, making a woodworking bench using a softwood would not be advisable. It wouldn’t be long before the benchtop would wear out and the joints would fall apart from the stresses they’d receive. When building any kind of load bearing piece, you need to consider the strength of the wood you choose. Softwoods crush easily, and under repeated stress, the joints will weaken and fail quickly.

Browse published woodworking plans in your search for project ideas. You may even stumble across a design and plan that will work for you, saving you a lot of time and energy. Since most published plans already are shop-tested, you can be fairly confident that they’re accurate (but it’s still a good idea to double-check as you read the plan).

As for the budget issue, you should certainly factor it in. If making your spice rack out of zebrawood means your material costs would be $100 instead of $20 for maple, ask yourself if the benefit is worth the extra cost. But be sure to consider the impact, if any, the species choice will have on the longevity of the product. If the zebrawood spice rack will last 50 years and the maple only three, which one is the better bargain? The old tool-buyer’s saw “Buy the best tool you can afford” can easily be applied to wood selection.

Another factor that should influence your wood species choices is the desire to match the piece you plan to build with the wood found in other furniture pieces and trim that will be in the same room. Before purchasing all your stock, get a sample of the lumber so you can see what it looks like with finish applied. Compare the sample to wood you’re trying to match.

Make concept drawings. They don’t need to be as pretty as the concept sketches shown above, but making a few drawings that capture the gist of the project will get the project-design ball rolling.

American Farm

Typical features: Elaborate “pressed” backrest with relief design, heavily beaded turned legs and spindles, caned seats.

Country

Typical features: Overall rustic appearance (although often achieved with complex construction methods).

Queen Anne

Typical features: Cabriole legs, upholstered seat, curved back legs with decorative center slat, spindle-turned spreaders.

The Essentials of Style

“Style” is a bit of a double-edged sword when it comes to woodworking. Borrowing from a particular furniture style is a good way to ensure that your project design will work out, but paying too much attention to the period of a piece can limit your creativity and even cause you to lose sight of the most basic goal: creating a nice furnishing for your home. But as you work through the basic questions you need to answer when starting to develop a project plan, it is still a good idea to take style into consideration—especially if the piece you build will coexist with other furnishings of a definite style.

Another good reason to consider style is that it can help you make some initial decisions about the difficulty of the project you want to attempt. If you’re a beginning woodworker, for example, you should consider some of the easier to build styles such as Mission, Shaker, country, contemporary, and modern. They tend to incorporate simple shapes with less complex construction techniques, and rely more on relative proportions to achieve their appearance than they do on complex details. This is not to say that these styles are not for more advanced woodworkers, since some pieces made in these styles can be very complex. It’s just that these styles are easy to simplify using modern woodworking techniques, thereby eliminating some or most of the complex joinery. More complex and detailed styles, such as early American, Victorian, classic, traditional, Queen Anne, and gothic, should not necessarily be ruled out from the outset. Making your piece using one of these styles may be challenging, but could also be very rewarding.

The photographs on these two pages give a good illustration of the effect style has on the appearance of a piece of furniture. By comparing and contrasting the characteristics of each of the nine chairs shown, you’ll get a fair idea of which features define each particular style type. Although some of the elements are unique to chairs, look for details you find appealing and, if you’re interested in tackling a period woodworking project, use the information as a starting point for investigating a little deeper into the style you like.

Folding Chairs

Typical features: Hinged legs and seat to fold flat, often slat-built, not technically a design “style” but still a good option.

Danish Modern

Typical features: Spare, open design, graceful curves, strong horizontal lines, often built with teak and dark non-wood accents.

Contemporary

Typical features: Irregular shapes, parts made from laminated sheet goods, no ornate detailing.

Windsor

Typical features: Arched back frame with spindle infills, scooped seats, splayed legs connected by spindle spreaders.

Shaker

Typical features: High backs, round or tapered legs, woven seats, simple and graceful appearance.

Mission

Typical features: Simple, square joints, narrower slats and spreaders, mortise-and-tenon joints, usually quartersawn oak.

The wood movement factor

One of the very first pieces I built was a solid oak coffee table that I made for my brother and sister-in-law. I was a novice woodworker way back then, and I didn’t know much about wood movement. I built the piece in the summertime using a design that defied the laws of wood movement. I delivered it and they were happy. Six months later, in the middle of winter, I got a call from my brother. He said: “The strangest thing happened last night. We heard this big bang. I went downstairs and found the coffee table you built us had exploded and was lying on the floor in pieces.” I haven’t made that mistake again.

~ Bruce Kieffer

Veneer

Making your own veneered panels is a great alternative to using manufactured plywood. Using veneer allows you to apply thin solid wood edgings to particleboard cores, and then apply the veneer on top of that construction. With the edging strip under the veneer, you get the look of a solid wood panel, but with a stable construction like plywood provides. Plus, using veneer gives you the opportunity to really get your creative juices flowing with all the different ways you can match the veneer sheets together. Using it is an option you should consider if you’re a moderately experienced woodworker and you want total control of the finished look of the project you plan to build. There are many good books available that can teach you how to make veneered panels if this technique is new to you. By veneering your own panels, you can also make “custom” sheet goods with unusual or exotic faces not found in lumber yards or building centers.

Exotic and distinctive veneer types include: (A) Zebrawood; (B) Birdseye maple; (C) African Padauk (vermillion); (D) Madrone burl; (E) Maple burl; (F) Purpleheart. All shown with oil finish.

Outdoor projects require rot-resistant lumber, like the cedar being used to build the planter above. The species of wood you’ll use can impact the longevity of your project.

Solid wood, plywood or veneer? Will you use only solid lumber, or a combination of solid lumber and hardwood plywood, or even make your own veneered panels? Once again, this decision is most often dictated by the style you’ve chosen. Sleek modern styled projects almost always are built using plywood with solid wood edgings. This is because of the necessity to account for wood movement. The doors and drawers used on modern styled pieces are flat panels with small gaps between the parts. Even if you live somewhere where the relative humidity is constant all year long, using solid wood for these parts would be a bad idea.

Choosing hardware & finishes. Decisions about functional hidden hardware such as concealed hinges, drawer slides, and fasteners, as well as decorative exposed hardware, such as butt hinges, and door and drawer handles, need to be made as part of the design process. If you’re trying to make a decision about some piece of functional hardware that’s new to you, and you’re not completely sure how it will work, then now’s the time to make a simple prototype. Let’s use a drawer slide as an example. Say you choose a new style drawer slide that you haven’t used before. Staple together four boards to imitate a cabinet, and four boards to imitate a drawer (this is as sophisticated as a prototype need be). Mount the slide and see that it functions as you want it to. Doing this will also give you an idea of how forgiving the mounting tolerances will be. This is important to know since it may require you to preform the construction with a greater degree of accuracy than you’re accustomed to.

Choosing your decorative hardware can be more difficult because of all the choices available. Looking in hardware catalogs is a great way to start, but you should make your final decisions with an actual piece of the decorative hardware in your possession.

The time to choose a finish is also during design, not after your project is built. You want to know far in advance how the finish will look and how it will be applied. Unless you’re very familiar with the finishing product you plan to use, you should test it on a large scrap of the actual project stock.

If you plan to stain your wood, you’ll need to make more involved samples. You need to find out in the design stage how the stain looks on a large sample, and you need to know how easy or difficult it is to apply. Some stains are harder to apply than others. Gel stains and other thick stains tend to be more difficult to apply, and oil stains somewhat easier. When planning to use a difficult-to-apply stain, make samples of inside corner joints. Since a stained inside corner has to be wiped cross grain, that can have a huge effect on how the stain looks there. To complete your stained samples, also apply the topcoat product you plan to use. The topcoat will alter the look of the stained board in most cases.

Use sheet goods to build cabinetry. Contemporary cabinets often are made with visible reveals between the doors and cabinet box. As a result, even a little warpage will be easily noticeable. Since plywood and other sheet goods are much more stable, you’re less likely to have warpage problems using them than with glued up solid wood panels.

Test hardware on working project prototypes, especially if you don’t have any experience with that type of hardware. Drawer slides, especially, vary a great deal in installation method and in acceptable tolerance for error, and they can impact the required size of the drawer opening.

Test finish products on scraps of the same type of wood to be used in your project. Once you’ve made a selection, retest your choice on a larger scrap board to get a more accurate idea of how the finished project parts would look.

Making Prototypes

At some point during the planing process you should consider making a prototype of your project. Prototypes can, and in most cases should be, crude and quick constructions. The intention here is to build a full-sized section of a part of the construction that you’re having difficulty working out in your mind or on paper. How much prototyping you need to do will depend on what it is you’re building. Here are some examples: Say you plan to build a large entertainment center and you want to see how big it really will be. Cut up large pieces of cardboard for the front, top and sides, and tape them together. Now you can see how big it really is. Or, say you plan to build a table with a routed edge, but you don’t know which routed profile to use. Make some large test wood pieces, rout some profiles, and see how they look. When you’ve narrowed down the choices, add wood pieces to approximate the table aprons and tabletop overhang.

Building any kind of seating is a must prototype situation. Start by sitting in a number of chairs or sofas and take measurements from them. Then prototype the seating you plan to build. I do this with 2 x 4’s and particleboard. If you start with the prototype a little short, you can easily add more pieces of particleboard to raise and test a higher seat. You just have to be able to sit comfortably in the prototype before you build the actual chair, or chances are the real thing won’t sit comfortably. If your seating will be cushioned, approximate the cushion thickness in your prototype too. Prototype everything you think you need to, but make it a quick process so you can get on to drawing your plans and then building your project.

Build scale models. Although not useful for testing mass or joinery, models give you a 3-D perspective on your plan as well as a sense of part proportion.

Prototype tricky joints by cutting full-sized workpieces from inexpensive wood, then building the joint. Among other advantages, this will help you decide which is the best tool for cutting the actual project joints.

Standard furniture dimensions:

Dining tables

Top height: 29 to 30 in.

Place setting width: 24 in. minimum, 30 in. optimum.

Table edge to pedestal base clearance: 14 in. minimum.

Apron to floor minimum clearance: 23½ in.

Miscellaneous tables Coffee tables: 12 to 18 in. tall.

End tables: 18 to 24 in. tall.

Desks

Depth: 30 in. deep.

Writing height: 29 in. to 30 in.

Computer keyboard stations: 25 in. to 27 in. tall.

Bedroom furniture Dressers: 18 to 24 in. deep, 30-in. minimum height.

Night stands: 18 to 22 in.

Bed mattress height: 18 to 22 in.

Chairs

Seat height: 15 to 18 in.

Seat width: 17 to 20 in.

Seat depth: 15 to 18 in.

Arm rest (from seat): 8 to 10 in.

Build a full prototype. You don’t have to use the actual wood stock or even make the parts look exactly like they will, but building a full-size, working prototype from inexpensive materials is a good idea, especially for seating projects.

Make a cardboard prototype. To get an idea of the actual footprint and mass of a larger project, rig up some pieces of cardboard to fit together in the rough project shape and dimensions. Actually position the prototype in the spot where you’re planning to put your project.

Scrapwood, particleboard, cardboard, sheetrock and paper are all good and cheap materials for making prototypes. Hot glue, drywall screws, staples, nails, duct tape, masking tape, contact cement and spray adhesives are all suitable fastening materials you can use to assemble prototypes.

In addition to prototypes, many designers like to build scale models of their designs. The models serve mostly a visual purpose, since testing a 1/10th size joint would be futile, if not impossible. Models can be made with a variety of materials, including cardboard, balsa wood, foam-core board or even construction paper. Or, you may want to resaw some of the actual stock you plan to use into thin strips, then use that to build the model. The main benefit models offer is a 3-D view of the project to give you a better sense of how the relative proportions work.

Standard furniture dimensions:

Lounge seating

Seat height: 14 to 17 in.

Seat width: 24 in. minimum per person.

Seat depth: 15 to 18 in.

Arm rest height from seat): 8 to 10 in.

Seat angle tilt backwards: 3° to 5°.

Backrest tilt angle from seat: 95° to 105°.

Bookcases

Depth: 12 in.

Height: 76 in. maximum.

Shelf width: 24 in. maximum width for ¾-in. plywood shelves; 36 in. maximum width for ¾-in. solid wood shelves.

Making Plan Drawings

To visualize and refine finer details such as overall and relative proportions, you’ll need to make “scaled” working drawings. A scaled drawing is basically a shrunk-down, yet correctly proportioned drawing that shows your project’s details and its dimensions. If you were drawing in ¼ scale, every real inch would equal 4 inches. The term “working” refers to the fact that you will follow these drawings closely when you build your project and use these drawings to determine the dimensions of the wood parts you need to cut.

To make professional-quality scaled working drawings you’ll need an architect’s scale, drafting table, T-square, 45° triangle, 30 x 60° triangle, and a compass for drawing circles. French curves are useful for drawing curved shapes. Other more specialized drafting tools are available at graphic design stores.

The architect’s scale. Many scale rulers are available, but an architect’s scale is the one used by most woodworkers. An architect’s scale is a ruler with six sides. Although architects use these scales to draw in feet increments, the architect’s scale is just as easily used to draw in inch increments, which is what most woodworkers do. The side with the number 16 marked at the left end is a full size ruler, meaning 1 inch equals 1 inch. The number 16 label means each inch is divided into sixteenths. The rest of the sides are marked with two different scales per side. One scale runs left to right, and the other runs right to left. To understand how to use an architect’s scale, start by looking at the side marked on the left end with the fraction 3/32. Using that side and working from left to right means that every 3/32 inch equals 1 inch. In this scale, the real measurement of 12 inches would equal 128 inches and those divisions are marked off with the upper row of numbers on that side. On the right end of the same side of the scale, is a fraction label that says “3/16.” Working from right to left and using the lower row of numbers marked on that side is the “3/16 inch equals 1 inch” scale. The other fraction-labeled scales work the same way. The sides with the ends labeled 1, 1½, and 3 are used for scaling at “1 inch equals 12 inches,” “1½ inch equals 12 inches,” and “3 inches equals 12 inches,” respectively.

Accurate, detailed plan drawings not only create a blueprint for your woodworking project, they help you determine part sizes and get a better sense of what your project will look like when completed. An assortment of drafting tools will make drawing scaled plans much easier. A triangle, circle template and an architect’s scale are shown in the photo above. For maximum benefit, draw your project from several different viewpoints.

Drafting tools for making project plan drawings include a smooth worksurface (a portable drafting table is shown here), a variety of pens and pencils including a mechanical pencil, an architect’s scale, a compass, a triangle or two and one or more french curves.

The architect’s scale