1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

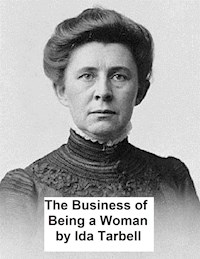

This book is a result of a thorough research conduct by the author Ida M. Tarbell. Tarbell's research in the backwoods of Kentucky and Illinois uncovered the true story of Lincoln's childhood and youth. She wrote to and interviewed hundreds of people who knew or had contact with Lincoln. She tracked down leads and then confirmed their sources. She sent hundreds of letters looking for images of Lincoln and found evidence of more than three hundred previously unpublished Lincoln letters and speeches.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

The Early Life of Abraham Lincoln

Table of Contents

THE EARLIEST PORTRAIT OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN.—HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED.

From a carbon enlargement, by Sherman and McHugh, New York, of a daguerreotype in the possession of the Hon. Robert T. Lincoln, and first published in the McClure’s Life of Lincoln. It is generally believed that Lincoln was not over thirty-five years old when this daguerreotype was taken, and it is certainly true that it shows the face of Lincoln as a young man. It is probably earlier by six or seven years, at least, than any other existing portrait of Lincoln.

Introduction

It has been only within the last ten years that the descent of Abraham Lincoln from the Lincolns of Hingham, Massachusetts, has been established with any degree of certainty. The satisfactory proof of his lineage is a matter of great importance. In a way it explains Lincoln. It shows that he came of a family endowed with the spirit of adventure, of daring, of patriotism, and of thrift; that his ancestors were men who for nearly two hundred years before he was born were active and well-to-do citizens of Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, or Virginia, men who everywhere played their parts well. Abraham Lincoln was but the flowering of generations of upright, honorable men.

The first we learn of the Lincolns in this country is between the years 1635 and 1645, when there came to the town of Hingham, Massachusetts, from the west of England, eight men of that name. Three of these, Samuel, Daniel, and Thomas, were brothers. Their relationship, if any, to the other Lincolns who came over from the same part of the country at about the same time is not clear. Two of these men, Daniel and Thomas, died without heirs; but Samuel left a large family, including four sons. Among the descendants of Samuel Lincoln’s sons were many good citizens and prominent public officers. One was a member of the Boston Tea Party, and served as a captain of artillery in the War of the Revolution. Others were privates in that war. Three served on the brig “Hazard” during the Revolution. Levi Lincoln, a great-great-grandson of Samuel, born in Hingham in 1749, and graduated from Harvard, was one of the minute-men at Cambridge immediately after the battle of Lexington, a delegate to the convention in Cambridge for framing a State Constitution, and in 1781 was elected to the Continental Congress, but declined to serve. He was a member of the House of Representatives and of the Senate of Massachusetts, and was appointed Attorney-General of the United States by Jefferson; for a few months preceding the arrival of Madison he was Secretary of State, and in 1807 he was elected Lieutenant-Governor of Massachusetts. In 1811 he was appointed Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court by President Madison, an office which he declined. From the close of the Revolutionary War he was considered the head of the Massachusetts bar.

His eldest son, Levi Lincoln, born in 1782, had also an honorable public career. He was a Harvard graduate, became Governor of the State of Massachusetts, and held other important public offices. He received the degree of LL.D. in 1824 from Williams College, and from Harvard in 1826.

Another son of Levi Lincoln, Enoch Lincoln, served in Congress from 1818 to 1826. He became Governor of Maine in 1827, holding the position until his death in 1829. Enoch Lincoln was a writer of more than ordinary ability.

The fourth son of Samuel Lincoln was called Mordecai (President Lincoln descended from him, being his great-great-great-grandson). Mordecai Lincoln was a rich “blacksmith,” as an iron-worker was called in those days, and the proprietor of numerous iron-works, saw-mills, and grist-mills, which with a goodly amount of money he distributed at his death among his children and grandchildren. Two of his children, Mordecai and Abraham, did not remain in Massachusetts, but removed to New Jersey, and thence to Pennsylvania, where both became rich, and dying, left fine estates to their children. Their descendants in Pennsylvania have continued to this day to be well-to-do people, some of them having taken prominent positions in public affairs. Abraham Lincoln, of Berks County, who was born in 1736 and died in 1806, filled many public offices, being a member of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania, of the State Convention of 1787, and of the State Constitutional Convention in 1790.

One of the sons of this second Mordecai, John (the great-grandfather of President Lincoln), received from his father “three hundred acres of land, lying in the Jerseys.” But evidently he did not care to cultivate his inheritance, for about 1758 he removed to Virginia. “Virginia” John, as this member of the family was called, had five sons, all of whom he established well. One of these sons, Jacob, entered the Revolutionary Army and served as a lieutenant at Yorktown.

The settlers of western Virginia were all in those days more or less under the fascination of the adventurous spirit which was opening up the West, and three of “Virginia” John’s sons decided to try their fortunes in the new country. One went to Tennessee, two to Kentucky. The first to go to Kentucky was Abraham (the grandfather of the President). He was already a well-to-do man when he decided to leave Virginia, for he sold his estate for some seventeen thousand dollars. A portion of this money he invested in land-office treasury warrants.

On emigrating to Kentucky he bought one thousand seven hundred acres of land. But almost at the beginning of his life in the new country, while still a comparatively young man, he was slain by the Indians. His estate seems to have been inherited by his eldest son, Mordecai, who afterward became prominent in the State; was a great Indian fighter, a famous story-teller, and, according to the traditions of his descendants, a member of the Kentucky legislature. This last item we have not, however, been able to verify. We have had the fullest collection of journals of the Kentucky legislature which exists, that of Dr. R. T. Durrett of Louisville, Kentucky, carefully searched, but no mention has been found in them of Mordecai Lincoln.

It is with the brother of Mordecai, the youngest son of the pioneer Abraham, we have to do, a boy who was left an orphan at ten years of age, and who in that rude time had to depend upon his own exertions. We find from newly discovered documents that he was the owner of a farm at twenty-five years of age, and from the contemporary evidence that he was a very good carpenter; from a document we have discovered in Kentucky we learn that he was even appointed a road surveyor, in 1816. We have found his Bible, a very expensive book at that time; we have also found that he had credit, and was able to purchase on credit a pair of suspenders costing one dollar and fifty cents, and we have learned from the recollections of Christopher Columbus Graham that in marrying the niece of his employer he secured a very good wife. The second child of Thomas Lincoln was Abraham Lincoln, who became the sixteenth President of the United States and the foremost man of his age.

The career of Abraham Lincoln is more easily understood in view of his ancestry. The story of his life, which is here told more fully and consecutively, and in many points, both minor and important, we believe more exactly than ever before, bears out our belief that Abraham Lincoln inherited from his ancestry traits and qualities of mind which made him a remarkable child and a young man of unusual promise and power. So far from his later career being unaccounted for in his origin and early history, it is as fully accounted for as in the case of any man.

So far as possible, the statements in this work are based on original documents. This explains why in several cases the dates differ from those commonly accepted. Thus the year of the death of the grandfather of Abraham Lincoln is made 1788, instead of 1784, because of the recently discovered inventory of his estate. The impression given of Thomas Lincoln is different from that of other biographies, because we believe the new documents we have found and the new contemporary evidence we have unearthed, justify us in it. We have not made it a sign of shiftlessness that Thomas Lincoln dwelt in a log cabin at a date when there was scarcely anything else in the State.

An effort has been made, too, to give what we believe to be a truer color to the fourteen years the Lincolns spent in southern Indiana. The poverty and the wretchedness of their life has been insisted upon until it is popularly supposed that Abraham Lincoln came from a home similar to those of the “poor white trash” of the South. There is no attempt made here to deny the poverty of the Lincoln household, but it is insisted that this poverty was a temporary condition incident to pioneer life and the unfortunate death of Thomas Lincoln’s father when he was but a boy. Thomas Lincoln’s restless efforts to better his condition by leaving Kentucky for Indiana in 1816, and afterwards, when he had discovered that his farm in Spencer County was barren, by trying his fortunes in Illinois, are sufficient proof that he had none of the indolent acceptance of fate which characterizes the “poor whites.”

In telling the story of the six years of Lincoln’s life in New Salem, we have attempted to give a consecutive narrative and to show the exact sequence of events, which has never been done before. We have shown, what seems to us very suggestive, the persistency and courage with which he seized every opportunity and carried on simultaneously his business as storekeeper and postmaster and surveyor and at the same time studied law. To establish the order of events in this New Salem period, the records of the county have been carefully examined, and many new documents concerning Lincoln have been found in this search, including his first vote, his first official document (an election return), and several new surveying plats. The latter show Lincoln to have been much more active as a surveyor than has commonly been supposed. We have also brought to light the grammar Lincoln studied, with a sentence written on the title page in Lincoln’s own hand.

For the first time, too, we publish documents signed by Lincoln as a postmaster. These two letters are also earlier than any other published letters of Lincoln. Many minor errors have been corrected, such as the real number of votes which he received on his first election to the legislature, and the times and places of his mustering out and into service in the Black Hawk War.

The number of illustrations in the work is many times greater than ever has before appeared in connection with the early life of Lincoln. The scenes of his life in Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois have been photographed especially for us, and we have collected from various sources numbers of pictures illustrating the primitive surroundings of his boyhood and young manhood, together with portraits of many of his companions in those days. Our object in giving such a profusion of homely scenes and faces has been to make a history of Lincoln’s early life in pictures. We believe that one examining these prints independently of the text would have a good idea of Lincoln’s condition from 1809 to 1836.

By far the most important of the illustrations of the work is the collection of portraits. This is the first systematic effort to make a complete collection of portraits of the great President. Our success so far encourages us in believing that before we end our work on Lincoln we shall have such a collection. Already we have some seventy-five different portraits. Of these, the great majority are photographs, ambrotypes, and daguerreotypes. It was Mr. Lincoln’s custom, after the introduction of photography into Illinois, to sit for his picture whenever he visited a town to make a speech. This picture he usually gave to his host; the result was that there now remain, scattered among his old friends, a large number of interesting portraits, of which nobody but the owners knew until we undertook this work. Thus of the twenty portraits which appear in this volume, twelve have never before been published anywhere, so far as we know.

It has been through the generosity and courtesy of collectors and of our correspondents and readers that it has been possible for us to gather so great a number of portraits and documents. On all sides collections have been put freely at our service, and numbers of our readers have sent us unpublished ambrotypes, daguerreotypes, and photographs, glad, as they have written us, to aid in completing a Lincoln portrait gallery. It is not possible to mention here the names of all those to whom we are indebted, not only for portraits but for documents and manuscripts, but credit is given in inserting the material furnished.

Our effort has been to give in both text and notes as exact and full statements as the information we have been able to gather permitted us to do. If any reader of this volume discovers errors we shall be glad to receive corrections.

LINCOLN IN 1854.—HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED.

From a photograph owned by Mr. George Schneider of Chicago, Illinois, former editor of the “Staats Zeitung,” the most influential anti-slavery German newspaper of the West. Mr. Schneider first met Mr. Lincoln in 1853, in Springfield. “He was already a man necessary to know,” says Mr. Schneider. In 1854 Mr. Lincoln was in Chicago, and Mr. Isaac N. Arnold, a prominent lawyer and politician of Illinois, invited Mr. Schneider to dine with Mr. Lincoln. After dinner, as the gentlemen were going down town, they stopped at an itinerant photograph gallery, and Mr. Lincoln had the above picture taken for Mr. Schneider. The newspaper he holds in his hands is the “Press and Tribune.”

LINCOLN IN 1863.

From a photograph by Brady, taken in Washington.

Chapter I.

The Origin of the Lincoln Family.—The Lincolns in Kentucky.

The family from which Abraham Lincoln descended came to America from Norfolk, England, in 1637. A brief table1 will show at a glance the line of descent:

Samuel Lincoln, born in 1620. Emigrated from Norfolk County, England, to Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1637. His fourth son was

Mordecai Lincoln, born in 1667. His eldest son was

Mordecai Lincoln, born in 1686. Emigrated to New Jersey and Pennsylvania, 1714. His eldest son was

John Lincoln, born before 1725. In 1758 went to Virginia. His third son was

Abraham Lincoln, date of birth uncertain. In 1780, or thereabouts, emigrated to Kentucky. His third son was

Thomas Lincoln, born in 1778, whose first son was

Abraham Lincoln, Sixteenth President of the United States.

LAND WARRANT ISSUED TO ABRAHAM LINCOLN, GRANDFATHER OF PRESIDENT LINCOLN.

From the original, owned by R. T. Durrett, LL.D., of Louisville, Kentucky. The land records of Kentucky show that Abraham Lincoln entered two tracts of land when in Kentucky in the spring and summer of 1780. These entries, furnished us by Dr. Durrett, are as follows: May 29, 1780.—“Abraham Linkhorn enters four hundred acres of land on Treasury Warrant, laying on Floyd’s Fork, about two miles above Tice’s Fork, beginning at a Sugar Tree S. B., thence east three hundred poles, then north, to include a small improvement.”—Land Register, page 107. June 7, 1780.—“Abraham Linkhorn enters eight hundred acres upon Treasury Warrant, about six miles below Green River Lick, including an improvement made by Jacob Gum and Owen Diver.”—Page 126. The first tract of land was surveyed May 7, 1785 (see page 23), and the second on October 12, 1784. In 1782 he entered a third tract of land, a record of which is found in Daniel Boone’s field-book. This entry reads: “Abraham Lincoln enters five hundred acres of land on a Treasury Warrant, No. 5994, beginning opposite Charles Yancey’s upper line, on the south side of the river, running south two hundred poles, then up the river for quantity; December 11, 1782.” This is supposed by some authorities to be a tract of five hundred acres of land in Campbell County, surveyed and patented in Abraham Lincoln’s name, but after his death. The spelling of the name Linkhorn instead of Lincoln, as it is invariably in other records of the family, has caused some to doubt that the Treasury warrant above was really issued to the grandfather of the President. The family traditions, however, all say that the elder Abraham owned a tract on Floyd’s Fork. The misspelling and mispronunciation of the name Lincoln is common in Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois. The writer of this note has frequently heard persons in Illinois speak of “Abe Linkhorn” and “Abe Linkern.”

FIELD NOTES OF SURVEY OF FOUR HUNDRED ACRES OF LAND OWNED BY ABRAHAM LINCOLN, GRANDFATHER OF PRESIDENT LINCOLN.

From the record of surveys in the surveyor’s office of Jefferson County, Kentucky, Book B., page 60.

HUGHES STATION, ON FLOYD’S CREEK, JEFFERSON COUNTY, KENTUCKY, WHERE ABRAHAM LINCOLN, GRANDFATHER OF THE PRESIDENT, LIVED.—NOW FIRST PUBLISHED.

From the original, owned by R. T. Durrett, LL.D., of Louisville, Kentucky. “The first inhabitants of Kentucky,” says Dr. Durrett, “on account of the hostility of the Indians, lived in what were called forts. They were simple rows of the conventional log cabins of the day, built on four sides of a square or parallelogram, which remained as a court, or open space, between them. This open space served as a playground, a muster field, a corral for domestic animals, and a store-house for implements. The cabins which formed the fort’s walls were dwelling-houses for the people.” At Hughes Station, on Floyd’s Creek, lived Abraham Lincoln and his family. One morning in 1788—the date of the death of Abraham Lincoln is placed in 1784, 1786, and 1788 by different authorities; the inventory of his estate (page 28) is dated 1788; for this reason we adopt 1788—the pioneer Lincoln and his three sons, Mordecai, Josiah, and Thomas, were in their clearing, when a shot from an Indian killed the father. The two elder sons ran for help, the youngest remaining by the dead body. The Indian ran to the side of his victim, and was just seizing the son Thomas, when Mordecai, who had reached the cabin and secured a rifle, shot through a loophole in the logs and killed the Indian. It was this tragedy, it is said, that made Mordecai Lincoln one of the most relentless Indian haters in Kentucky.

For our present purpose it is not necessary to examine the lives of these ancestors farther back than the grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, who has been supposed to have been born in Virginia in 1760. A consideration of the few facts we have of his early life shows clearly that this date is wrong. It is known that in 1773 Abraham Lincoln’s father, John Lincoln, conveyed to his son a tract of two hundred and ten acres of land in Virginia, which he hardly would have done if the boy had been but thirteen years of age. We know, too, that in 1780 Abraham Lincoln had a wife and five children, the youngest of whom was at least two years old. Evidently he must have been over twenty years of age, and have been born before 1760. Probably, too, his birthplace was Pennsylvania, whence his father moved into Virginia about 1758.

Daniel Boone

RELICS OF DANIEL BOONE.

Photographed for this work from the originals, in the collection of pioneer relics owned by R. T. Durrett, LL.D., of Louisville, Kentucky. The articles are a rifle, scalping-knife, powder-horn, tomahawk, and hunting-shirt. Dr. Durrett has all the documents needful to establish the authenticity of each of these articles. They unquestionably were used by Boone through a long period of hunting and Indian stalking; all of the articles are well preserved, and even the leather coat is still fit for service. The rifle, says Dr. Durrett, is as true as it ever was. In this same collection are a large number of similar relics of other Kentucky pioneers.

Abraham Lincoln was a farmer, and, by 1780, a rich one for his time. This we know from the fact that in 1780 he sold a tract of two hundred and forty acres of land for “five thousand pounds of current money of Virginia;” a sum equal to about $17,000 at that date. This sale was made, presumably, because the owner wished to move to Kentucky. He and his family had for several generations back been friends of the Boones. The spell the adventurous spirit of Daniel Boone cast over all his friends, Abraham Lincoln felt; and in 1780, soon after selling his Virginia estate, he visited Kentucky, and entered two large tracts of land. Some months later he moved with his family from Virginia into Kentucky.

Abraham Lincoln was ambitious to become a landed proprietor in the new country, and he entered a generous amount of land—four hundred acres on Long Run, in Jefferson County; eight hundred acres on Green River, near Green River Lick; five hundred acres in Campbell County. He settled near the first tract, where he undertook to clear a farm. It was a dangerous task, for the Indians were still troublesome, and the settlers, for protection, were forced to live in or near forts or stations. In 1784, when John Filson published his “History of Kentucky,” though there was a population of thirty thousand in the territory, there were but eighteen houses outside of the stations. Of these stations, or stockades, there were but fifty-two. According to the tradition in the Lincoln family, Abraham Lincoln lived in one of these stockades.

LONG RUN BAPTIST MEETING-HOUSE.

From the original drawing, owned by R. T. Durrett, LL.D., of Louisville, Kentucky. This meeting-house was built on the land Abraham Lincoln, grandfather of the President, was clearing when killed by Indians. It was erected about 1797.

All went well with him and his family until 1788. Then, one day, while he and his three sons were at work in their clearing, an unexpected Indian shot killed the father. His death was a terrible blow to the family. The large tracts of land which he had entered were still wild, and his personal property was necessarily small. The difficulty of reaching the country at that date, as well as its wild condition, made it impracticable for even a wealthy pioneer to own more stock or household furniture than was absolutely essential. Abraham Lincoln was probably as well provided with personal property as most of his neighbors, and much better than many. He had, for a pioneer, an unusual amount of stock, of farming implements, and of tools; and his cabin contained comforts which were rare at that date. The inventory of his estate, recently found at Bardstown, Kentucky, and here published for the first time, gives a clearer idea of the life of the pioneer Lincoln, and of the condition in which his wife and children were left, than any description could do:

Inventory of Abraham Lincoln’s Estate.2—Now First Published.

“At the meeting of the Nelson County Court, October 10, 1788, present Benjamin Pope, James Rogers, Gabriel Cox, and James Baird, on the motion of John Coldwell, he was appointed administrator of the goods and chattels of Abraham Lincoln, and gave bond in one thousand pounds, with Richard Parker security.

“At the same time John Alvary, Peter Syburt, Christopher Boston, and William [John (?)] Stuck, or any three of them, were appointed appraisers.

“March 10, 1789, the appraisers made the following return:

£.

s.

d.

1

Sorrel horse

8

1

Black horse

9

10

1

Red cow and calf

4

10

1

Brindle cow and calf

4

10

1

Red cow and calf

5

1

Brindle bull yearling

1

1

Brindle heifer yearling

1

Bar spear-plough and tackling

2

5

3

Weeding hoes

7

6

Flax wheel

6

Pair smoothing-irons

15

1

Dozen pewter plates

1

10

2

Pewter dishes

17

6

Dutch oven and cule, weighing 15 pounds

15

Small iron kettle and cule, weighing 12 pounds

12

Tool adds

10

Handsaw

5

One-inch auger

6

Three-quarter auger

4

6

Half-inch auger

3

Drawing-knife

3

Currying-knife

10

Currier’s knife and barking-iron

6

Old smooth-bar gun

10

Rifle gun

55

Rifle gun

3

10

2

Pott trammels

14

1

Feather bed and furniture

5

10

Ditto

8

5

1

Bed and turkey feathers and furniture

1

10

Steeking-iron

1

6

Candle-stick

1

6

One axe

9

£68

16

s.

6

d.

Peter Syburt, Christopher Boston, John Stuck.”

THE REV. JESSE HEAD.

From an original drawing in the possession of R. T. Durrett, LL.D., of Louisville, Kentucky. The Rev. Jesse Head was a Methodist preacher of Washington County, Kentucky, who married Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. Christopher Columbus Graham, who was at the wedding, and who knew Mr. Head well, says: “Jesse Head, the good Methodist preacher who married them, was also a carpenter or cabinet-maker by trade, and, as he was then a neighbor, they were good friends. He had a quarrel with the bishops, and was an itinerant for several years, but an editor and county judge afterwards in Harrodsburg.... The preacher, Jesse Head, often talked to me on religion and politics, for I always liked the Methodists. I have thought it might have been as much from his free-spoken opinions as from Henry Clay’s American-African colonization scheme, in 1817, that I lost a likely negro man, who was leader of my musicians.... But Jesse Head never encouraged any runaway, nor had any ‘underground railroad.’ He only talked freely and boldly, and had plenty of true Southern men with him, such as Clay.”—See Appendix.

Soon after the death of Abraham Lincoln, his widow moved from Jefferson County to Washington County. The eldest son, Mordecai, who inherited nearly all of the large estate, became a well-to-do and popular citizen. The deed-book of Washington County still contains a number of records of lands bought and sold by him. At one time he was sheriff of his county, and, again, its representative in the legislature of the State. Mordecai Lincoln is remembered especially for his sporting tastes and his bitter hatred of the Indians. General U. F. Linder of Illinois, who, as a boy, lived near Mordecai Lincoln in Kentucky, says: “I knew him from my boyhood, and he was naturally a man of considerable genius; he was a man of great drollery, and it would almost make you laugh to look at him. I never saw but one other man whose quiet, droll laugh excited in me the same disposition to laugh, and that was Artemus Ward. He was quite a story-teller. He was an honest man, as tender-hearted as a woman, and, to the last degree, charitable and benevolent.

“Lincoln had a very high opinion of his uncle, and on one occasion said to me: ‘Linder, I have often said that Uncle Mord had run off with all the talents of the family.’

“Old Mord, as we sometimes called him, had been in his younger days a very stout man, and was quite fond of playing a game of fisticuffs with any one who was noted as a champion. His sons and daughters were not talented like the old man, but were very sensible people, noted for their honesty and kindness of heart.” Mordecai remained in Kentucky until late in life, when he removed to Hancock County, Illinois.

MARRIAGE BOND OF THOMAS LINCOLN.

From a tracing of the original, made by Henry Whitney Cleveland.

Of Josiah, the second son, we know very little more than that the records show that he owned and sold land. He left Kentucky when a young man, to settle on the Blue River, in Harrison County, Indiana, and there he died. The two daughters married into well-known Kentucky families: the elder, Mary, marrying Ralph Crume; the younger, Nancy, William Brumfield.

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATE OF THOMAS LINCOLN AND NANCY HANKS.—HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED.

From the original, in the possession of Henry Whitney Cleveland of Louisville, Kentucky. This interesting document, discovered by Mr. Cleveland, and published for the first time in this biography, completes the list of documentary evidence of the marriage of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. The bond given by Thomas Lincoln and the returns of Jesse Head, the officiating clergyman, were discovered some years ago, but the marriage certificate was unknown until recently discovered by Mr. Cleveland.

Thomas Lincoln’s Boyhood and Young Manhood.

The death of Abraham Lincoln was saddest for the youngest of the children, a lad of ten years at the time, named Thomas, for it turned him adrift to become a “wandering laboring-boy” before he had learned even to read. Thomas seems not to have inherited any of the father’s estate, and from the first to have been obliged to shift for himself. For several years he supported himself by rough farm work of all kinds, learning, in the meantime, the trade of carpenter and cabinet-maker. According to one of his acquaintances, “Tom had the best set of tools in what was then and now Washington County,” and was “a good carpenter for those days, when a cabin was built mainly with the axe, and not a nail or bolt-hinge in it; only leathers and pins to the door, and no glass, except in watches and spectacles and bottles.”3 Although a skilful craftsman for his day, he never became a thrifty or ambitious man. “He would work energetically enough when a job was brought to him, but he would never seek a job.” But if Thomas Lincoln plied his trade spasmodically, he shared the pioneer’s love for land, for when but twenty-five years old, and still without the responsibility of a family, he bought a farm in Hardin County, Kentucky. None of his biographers have ever called attention to this fact, if they knew it. A search made for this work in the records of Hardin County first revealed it to us, and we cannot but regard it as of importance, proving as it does that Thomas Lincoln was not the shiftless man he has hitherto been pictured. Certainly he must have been above the grade of the ordinary country boy, to have had the energy and ambition to learn a trade and secure a farm through his own efforts by the time he was twenty-five. He was illiterate, never doing more “in the way of writing than to bunglingly write his own name.” Nevertheless, he had the reputation in the country of being good-natured and obliging, and possessing what his neighbors called “good strong horse-sense.” Although he was “a very quiet sort of man,” he was known to be determined in his opinions, and quite competent to defend his rights by force if they were too flagrantly violated. He was a moral man, and, in the crude way of the pioneer, religious.

RETURN OF MARRIAGE OF THOMAS LINCOLN AND NANCY HANKS.

From a tracing of the original, made by Henry Whitney Cleveland. This certificate was discovered about 1885 by W. F. Booker, Esq., Clerk of Washington County, Kentucky.

LINCOLN IN FEBRUARY, 1860, AT THE TIME OF THE COOPER INSTITUTE SPEECH.

From a photograph by Brady. The debate with Douglas in 1858 gave Lincoln a national reputation, and the following year he received many invitations to lecture. One came from a young men’s Republican club in New York,—which was offering a series of lectures designed for an audience of men and women of the class apt to neglect ordinary political meetings. Lincoln consented, and in February, 1860 (about three months before his nomination for the Presidency), delivered what is known, from the hall in which it was delivered, as the “Cooper Institute speech”—a speech which more than confirmed his reputation. While in New York he was taken by the committee of entertainment to Brady’s gallery, and sat for the portrait reproduced above. It was a frequent remark with Lincoln that this portrait and the Cooper Institute speech made him President.

From a photograph by Klauber of Louisville, Kentucky. Mr. Graham, born in 1784, lived until 1885, and was the only man of our generation who could be called a contemporary of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. Long before the documentary evidence of their marriage was found, Mr. Graham gave his reminiscences of that event. Recent discoveries made in the public records of Kentucky regarding the Lincolns, bear out in every particular his recollections. He is, in fact, the most important witness we have as to the character of the parents of President Lincoln and their condition in life. The accuracy of his memory and the trustworthiness of his character are affirmed by the leading citizens of Louisville, Kentucky, of which city he was a resident. In the Appendix will be found a full statement by Mr. Graham of what he knew of Thomas Lincoln and his life.

FACSIMILE OF A PASSAGE FROM LINCOLN’S EXERCISE-BOOK.

HOUSE IN WHICH ABRAHAM LINCOLN WAS BORN.—HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED.

Thomas Lincoln moved into this cabin on the Big South Fork of Nolin Creek, three miles from Hodgensville, in La Rue County, Kentucky, in 1808; and here, on February 12, 1809, Abraham Lincoln was born. In 1813 the Lincolns removed to Knob Creek. The Nolin Creek farm has been known as the “Creal Farm” for many years; recently it was bought by New York people. The cabin was long ago torn down, but the logs were saved. The new owners, in August, 1895, rebuilt the old cabin on the original site. This, the first and only picture which has been taken of it, was made for this biography.