21,03 €

Mehr erfahren.

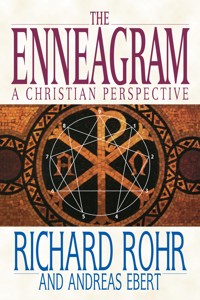

Richard Rohr and Andrea Ebert's runaway best-seller shows both the basic logic of the Enneagram and its harmony with the core truths of Christian thought from the time of the early Church forward.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 616

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2001

Ähnliche

This Printing: June 2016

www.CrossroadPublishing.com

Original German edition published as Das Enneagram: Die 9 Gesichter der Seele

copyright © Claudius Verlag, Munich, 1989

Revised and expanded German edition copyright © Claudius Verlag, Munich, 1999

English translation of the first German edition published as Discovering the Enneagram: An Ancient Tool for a New Spiritual Journey, copyright © 1990 by the Crossroad Publishing Company.

This translation of the revised and expanded German edition copyright © 2001 by the Crossroad Publishing Company.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the Crossroad Publishing Company.

Front cover art: A mandala in mosaic at Ascension Church, in Oak Park, Illinois © Regina Kuehn.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rohr, Richard.

[Enneagram. English]

The enneagram: a Christian perspective / by Richard Rohr and Andreas Ebert.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8245-0121-1

1. Enneagram. 2. Spiritual life-Catholic Church. I. Ebert, Andreas. II. Title.

BX2350.3 .R6413 2001

248.2-dc21

2001002356

For our mothers

Eleanore Dreiling-Rohr

Renate Apfelgrün-Mayr

I am afraid to drive the demons from my life lest the angels also flee.

—R. M. Rilke

And God showed me that sin will be no shame, but somehow honor for humanity. . . . God’s goodness makes the contrariness which is in us very profitable for us.

—Blessed Julian of Norwich

The angels of darkness must disguise themselves as angels of light.

—2 Corinthians 11:14

Contents

Preface: A Mirror of the Soul, Andreas Ebert

Preface: Discernment: How to See, How to Hear Richard Rohr

Part I

THE SLEEPING GIANT

A Dynamic Typology

The Mystery of the Number 153

Ramón Lull, 1236–1315

Breakthrough to the Totally Other

A Cardinal Wakes Up

A Sobering Aha-Experience

Gifted Sinners

The Truth Is Simple and Beautiful

People Are Creatures of Habit

Obsessions

The Way to Self-Worth

Wrong Ways and Ways Out

The Three Centers: Gut, Heart, Head

The Nine Faces of the Soul

Part II

THE NINE TYPES

Preface to Part II: Original Sin, Richard Rohr

Type ONE: The Need to Be Perfect

Type TWO: The Need to Be Needed

Type THREE: The Need to Succeed

Type FOUR: The Need to Be Special

Type FIVE: The Need to Perceive

Type SIX: The Need for Security

Type SEVEN: The Need to Avoid Pain

Type EIGHT: The Need to Be Against

Type NINE: The Need to Avoid

Part III

INNER DIMENSIONS

Repentance and Reorientation

Idealized Self-Image and Guilt Feelings

Temptation, Avoidance, Resistance

The Triple Continuum

Growing with the Enneagram

Jesus and the Enneagram

The Enneagram and Prayer

The End of Determinism

An Enneagram Sermon on Christmas, Dietrich Koller

The Repentance No One Regrets: Perspectives on Spiritual Work, Dietrich Koller

Notes

Index

Summary Tables

Preface

A Mirror of the Soul

Andreas Ebert

In the late summer of 1989 three books on the Enneagram appeared in German-speaking bookstores within the space of a few weeks. One of them was the first edition of this book. Since then more than three hundred thousand copies of it have been handed across shop counters, and the original text has been translated into many other languages. Richard Rohr and I have given numerous lectures and conferences on the Enneagram. The German “Ecumenical Enneagram Working Group” (based in Celle), which has more than five hundred members, has developed a lively organizational life. We have had the opportunity of getting to know other important Enneagram teachers and learning from them. And so it was high time to rework and update our book. But we have given up any really grand-scale solution. That would have meant rewriting the book and working into it the flood of literature that has since come out. We have decided instead on a small-scale solution, since our readers can acquire an overview of the Enneagram itself through other approaches and perspectives. Our book has remained substantially the same. We have inserted only the new insights that we ourselves have come upon and that have become especially important to us. This relates especially to the history of how the Enneagram came into being. Since the first edition we have become convinced that the Enneagram does not derive from medieval Islamic (Sufi) sources, but can be traced back, at least in part, to the Christian desert monk Evagrius Ponticus (d. 399) and the Franciscan Blessed Ramón Lull (1236–1315). Above and beyond that, we have made a few stylistic improvements.

The original text of this book has an unusual prehistory. In 1985 when I visited Richard Rohr, he was still the leader of the New Jerusalem family community in Cincinnati. He first introduced me to the Enneagram, which he was using in the framework of pastoral care for his community. At that point there was scarcely anything in print on the Enneagram.

In the summer of 1988 I had a chance to take part, at Richard Rohr’s new place, the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in an Enneagram workshop lasting several days. Meanwhile the situation in the United States had changed. Since the mid-1980s a whole series of books on the Enneagram had appeared; many psychologists and theologians were now of the opinion that the Enneagram was an excellent tool to help people on their way to spiritual and mental growth.

After my return from the United States I hesitated whether to translate one of the Enneagram books that had been published in America or instead make a book out of Richard Rohr’s taped workshop, with his impromptu talks. For various reasons I chose the latter option. Richard Rohr was already familiar to the German-speaking public thanks to his books The Wild Man and The Naked God. I felt that his style of lecturing—not always systematic, but lively and spontaneous—was more appropriate for communicating the Enneagram than a presentation with high scholarly pretensions.

In addition, I have also taken pains to work up the literature that has since appeared. This applies above all to the first and third parts of this book. Beyond that, I had already gathered a series of my own experiences with the Enneagram, and they too have made their way into this edition.

While working on this book, I learned that here and there—and unbeknownst to anyone—in the German-speaking world, people had been dealing with the Enneagram. A number of Jesuits and the Catholic “Communities of Christian Life” had used it for retreats and the training of spiritual counselors. In particular, the final product owes essential impulses to Hildegard Ehrtmann, whose participation in Enneagram work was crucial.

Finally, I have made use here of the feedback from one of the first German Enneagram conferences, which took place in 1989 at Schloss Craheim in Lower Franconia. Almost seventy participants, including a number of pastors and therapists, critically examined the concept and gave me valuable feedback.

Special thanks must go to Marion Küstenmacher, who was an editor at Claudius Verlag back then. She accompanied the creation of the book from the beginning and kept spurring it on with her enthusiasm. Since then she herself has become an internationally known and respected Enneagram teacher and author.

As I did before, today I wish that this book may have readers ready to dare to take the exciting and laborious path to self-knowledge and conversion. As I did before, I see a danger of a typological model like the Enneagram being misused to thoughtlessly force oneself and others into a schematic mold, and thereby not grow, but become fossilized. When misused, the Enneagram can be more of a curse than a blessing.

Self-knowledge is tied in with inner work, which is both demanding and painful. Change occurs amid birth pangs. It takes courage to walk such a path. Many avoid the path of self-knowledge because they are afraid of being swallowed up in their own abysses. But Christians have confidence that Christ has lived through all the abysses of human life and that he goes with us when we dare to engage in sincere confrontation with ourselves. Because God loves us unconditionally—along with our dark sides—we don’t need to dodge ourselves. In the light of this love the pain of self-knowledge can be at the same time the beginning of our healing.

The masters and soul guides of all spiritual traditions of the West and East have known that true self-knowledge is the presupposition of the “inner journey.” Teresa of Avila, the great Christian mystic, writes in her masterpiece The Interior Castle:

Not a little misery and confusion arise from the fact that through our own guilt we do not understand ourselves and do not know who we are. Would it not seem a terrible ignorance if one had no answer to give to the question, who one was, who his parents were, and from what country he came? If this were a sign of bestial incomprehension, an incomparably worse stupidity would prevail in us, if we did not take care to learn what we are, but contented ourselves with these bodies, and consequently knew only superficially, from hearsay, because faith teaches us, that we had a soul. But what treasures this soul may harbor within it, who dwells in it, and what great value it has, these are things we seldom consider, and hence people are so little concerned with preserving their beauty with all care.1

The Enneagram arises out of a perspective of human psychic strivings, whose roots go back at least as far as the early monasticism of the Desert Fathers, perhaps even back to pre-Christian times (Pythagoras). Later, it was presumably passed on orally through the Islamic wisdom tradition of Sufism. Thus, although it seems to be genuinely Christian, it draws from pre-Christian sources and has had an influence on non-Christian mystical traditions. These mystical currents of the major religions come astonishingly close to one another in view of both the religious experiences that they transmit and the worldview that they formulate. This is one of the reasons why there are Enneagram adherents from the most varied philosophical and religious backgrounds. Indeed, the Enneagram seems to be an instrument that supplies a lingua franca with a minimum of baggage. It can also be a bridge that people can step onto from different sides and in the middle of which they can meet. Many international Enneagram conferences with representatives from the most varied psychological and philosophical schools have given impressive proof of this in the last ten years. Thus it serves intercultural and interreligious dialogue.

The mystical image of the human being can be formulated roughly as follows: above all in the first half of our lives we construct our “empirical ego,” which can also be understood as the sum of our attitudes and behavioral mechanisms. The overidentification with such roles, habits, and character features is the chief obstacle in our search for our (true) “self.”

All mystical ways offer methods for unmasking this illusionary self—whether through knowledge, asceticism, good works, or meditation. A text from the German mystic Johannes Tauler brings the point at issue into focus:

When a person continually practices self-communion, the human ego has nothing for itself. The ego would be glad to have something, and would be glad to know something and to will something. Until this threefold “something” dies in us, we have a wretched time of it. This does not happen in a day nor in a short time. Rather one must force ourselves to it, must become used to it with keen industry. We must hold out until it finally becomes easy and pleasurable.

The New Testament calls Christians to the “discernment of spirits” (1 John 4:1). “Test everything; hold fast what is good” (1 Thess. 5:21). Paul trusts the community’s capacity to decide what it can critically adopt and what it can’t. In principle, the whole world and everything in it that is good, true, and beautiful is at the disposal of Christians: “For all things are yours. . . and you are Christ’s” (1 Cor. 3:21, 23).

In their writings Paul himself and John the Evangelist have taken over and “baptized”2 ideas and images from the Greek philosophy of religion of their own day. Thus John describes Christ as the incarnate Logos (John 1). The notion of the Logos implied that there is a kind of world reason that lies behind everything visible and rules in all things. Logos denotes rather precisely what “esoteric” thinkers nowadays call “highest consciousness.” John does not shy away from taking over this “esoterically handicapped” term. He recasts it and in that way he explains the Gospel to his contemporaries in linguistic categories that they understand.

In Christianity redemption from the false self is understood as a gift of God’s grace. What is disputed is the extent to which we ourselves can prepare ourselves, dispose and open ourselves, or accommodate ourselves to this grace. The problem is generally resolved by saying that we should pray as if it all depended on God and act as though everything depended upon ourselves. Paul already formulates this insoluble paradox of the human struggle and God’s grace in this way: “Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling. It is God, for his own loving purpose, who puts both the will and the action into you” (Phil. 2:12–13).

In the Eastern religions the participation of the person in redemption is more strongly emphasized, although the aspect of grace—for example in Buddhism—is definitely present. The flat assertion one hears from many Christians that the Eastern ways are nothing but self-redemption reveals crude ignorance. It is true that there is more agreement among the religions on their analysis of the question than on the answer. But Tauler’s text shows that even mystical practice—despite different concepts of grace—is very similar.

Christians are inclined to speak with great gusto about how grace alone is efficacious, but we have no answers when people ask how they can experience this redeeming, life-changing grace. Nowadays many people report that the ways of the East have helped them to rediscover their blocked-up faith or to deepen their prayer life. Serious Eastern spiritual teachers send their Christian adepts back to their own tradition. Many have to take detours only to find to their astonishment that in Christian tradition too they can discover everything that Eastern wisdom teaches.

Besides, the church has always “baptized” non-Christian perspectives. In the twentieth century it was primarily the findings of the human sciences that were “baptized” by Christian spiritual advisors, because they proved useful for the understanding of psychic (and social) events. As early as 1927 the conservative Norwegian theologian Ole Hallesby borrowed the idea of the four temperaments from the Greek physician and philosopher Hippocrates and made it fruitful for Christian pastoral care.3 In the last few decades Fritz Riemann’s idea of the “basic forms of anxiety” has been accepted by Christian counselors, even though Riemann developed his four types from his astrological speculation.4 Despite their “non-Christian” origin such models have proved useful instruments of pastoral care. This is all the more true for the Enneagram, which has genuinely Christian features.

At the end of the Bible the visionary John paints the picture of the new Jerusalem, the future City of God. In this context he describes how the peoples of the earth bring their gifts into this city (Rev. 21:26). This image implies that everything valuable in the thoughts and experiences of nations and religions belongs to the one God. We can gratefully lay claim to these gifts. The transfer of wisdom between religions is in my opinion one of the most essential contributions to world peace.

I believe that the Enneagram can help us to find a deeper and more authentic relationship with God—even though it was not discovered by Christians. Any of us with eyes can discover in it our own face, the face of God, and—as in an icon—the face of Christ. Paul writes: “Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit” (2 Cor. 3:17–18).

As a mirror of the soul the Enneagram remains a tool that can be laid aside at any time. The Enneagram is not the answer, but one signpost among many. Signposts show the way, but we have to take the way ourselves. I am glad that since the first edition of this book appeared—as far as I know—no one has succumbed to the temptation to exalt the Enneagram into a new absolute doctrine of salvation or to create a sect of Enneagramites. The Enneagram is only a cognitive model—though an amazingly comprehensive one. Our knowledge, as Paul says (1 Cor. 13), remains “partial” all our lives. Until God perfects us and the world, it is advisable to realize and do what can be realized and done—and leave the rest to God.

Discernment: How to See, How to Hear

Richard Rohr

They look without seeing, they listen without hearing or understanding, so I must teach them in a parabolic way.

—Matthew 13:13

All the Christian churches are being forced to an inevitable, honest, and somewhat humiliating conclusion. The vast majority of Christian ministry has been concerned with “churching” people into symbolic, restful, and usually ethnic belonging systems rather than any real spiritual transformation into the mystery of God. After serving as a priest for over thirty years, working with church groups of every kind on all continents as both personal confessor and as consultant for dioceses, monasteries, religious superiors, parishes, many different denominations, and every kind of renewal program for the laity, I am convinced that most of our ministries have legitimated the autonomous self and even fortified it with all kinds of religious armor. Religious people are even harder to transform because they don’t think they need it. They are “Catholics”! I find much more openness and response at the county jail than among the typical group of churchgoers. The incarcerated know that the separate self has not served them well. One wonders if this typical religious intransigence is not what Jesus is referring to by “the sin against the Holy Spirit.”

Much of what is called Christianity has more to do with disguising the ego behind the screen of religion and culture than any real movement toward a God beyond the small self, and a new self in God. Much of our work feels like cosmetic piety, and often shame or fear-based at that, rather than any real transformation of the ego self, or what the Eastern churches rightly call “divinization.” Much of the present attraction to other religions is quite simply because Christianity has not succeeded innaming the real evils well. Does this need any proof after the last century in Christian Europe? There are few confessors who would not agree that the vast majority of Catholic confessions have to do with pragmatic problem solving and supposed “sins” that divert our attention from the real evils that are destroying Western society. The present practice actually trivializes the immensity and urgency of our moral need. We cannot be quiet about this any longer to protect the institution. Nor was Jesus: “You blind guides, you strain out the gnat and swallow the camel!” (Matt. 23:24). The moral issues and the diversionary tactics of the ego never seem to change.

Only today I came across this courageous quote from Thomas Merton written in 1956, and it told me that my perceptions are not just mine or not just now. In The Living Bread, Merton wrote:

The great tragedy of our age is the fact, if one may dare to say it, that there are so many godless Christians—Christians, that is, whose religion is a matter of pure conformism and expediency. Their “faith” is little more than a permanent evasion of reality—a compromise with life. In order to avoid admitting the uncomfortable truth that they no longer have any real need for God or any vital faith in Him, they conform to the outward conduct of others like themselves. And these “believers” cling together, offering one another an apparent justification for lives that are essentially the same as the lives of their materialistic neighbours whose horizons are purely those of the world and its transient values.1

The Enneagram has emerged as a tool that is forcing many of us to a brutal and converting honesty about good and evil and the ways that we hide from ourselves and therefore hide from God. It tries to address this “compromise with life” and this “evasion of reality” that the ego is so invested in and that religion often promotes. Thomas Merton was a true seer, in my opinion. Another contemporary seer, Ken Wilbur, says that the vast majority of religion is “translative” rather than transformative. It is concerned with bolstering up the separate self with meanings, rituals, moralities, and group conformity rather than “dismantling” the separate self so it can fall into the Great Self of God. We have had far too much priesthood and almost no room for prophets. It creates a very imbalanced religion.

Andreas Ebert and I again offer the Enneagram as a very ancient Christian tool for the discernment of spirits, the struggle with our capital sin, our “false self,” and the encounter with our True Self in God. Anything this powerful and this converting is sure to be fought and resisted by the egocentric self, and even by control-needy prelates. We do not give up control to God easily. That is the story and testimony of every saint, mystic, and spiritual reformer. But the church, strange as it seems, has always been a bit uncomfortable with saints and mystics; it is content just to have people “in the pews.” Let’s be honest, we would sooner have control than real conversion; we would sooner have well-oiled church societies than transformed people. Cosmetic piety takes away our anxiety about God and about ourselves, but it does not address the real and subtle ways that we “lose our soul.”

Cosmetic piety never asks the hard questions of itself or of the church structures. Jesus challenged both—constantly. For some reason it is “hidden in plain sight” in all four Gospels! He knew that when religion is healthy, people are healthy. When religion is the conscience of society instead of its lapdog, culture is also healthy. We must acknowledge our part in the disintegration of Western civilization. If our culture has become soft and superficial, it is because religion did first—and not with regard to the “hot sins,” but with regard to those, oh, so subtle ways in which people slowly stop seeing, loving, trusting, and surrendering. We stopped seeing and trusting what our own Catholic tradition had taught us about the high price of conversion. We substituted law and authority for the ancient and much more difficult path of spiritual warfare, that subtle discernment of spirits, passions, and “energies” that the Desert Fathers and Mothers took as normative. In so many ways, the traditional churches are not traditional at all.

It seems that human beings cannot see what they are not readied to see. We cannot hear what we have not been prepared to hear. The “obvious” seems to have little correlation with our acceptance of it. We all have an amazing capacity for missing the point. This very traditional tenet of religion is the foundational insight of the Enneagram. Even education or important roles do not insure a full understanding of issues when our own personal investment is involved. It seems there is always a level beneath the obvious level that predetermines how we see, what we see, what we don’t see, and our preconscious and emotional reaction to it. At the New Jerusalem Community in Cincinnati, we used to say, “The issue is hardly ever the issue.” How discouraging and how disappointing, if that is true!

But because it is true, religion has always distinguished education from transformation. Being informed is different from being formed, and the first is a common substitute for the second. Even Supreme Court justices, bishops, and heads of state are often informed with facts but not formed anew. They often have correct data, but not a new viewpoint or a new Self. They are trapped inside the small self and daring to think they can speak for the Great Self. They read the situation “correctly,” but somehow it is all wrong and we know it. But we can’t prove it—to ourselves or to them. This is the powerlessness of saints and geniuses.

According to the chemist-turned-philosopher Michael Polanyi, all knowing of truth can happen only inside a previous “tacit knowing” that is silent, unconscious, and unspoken—even to us. Text is always untrue or at least incomplete outside of context. He subverted all claims to perfect objectivity in science, philosophy, and religion. He never denied objective reality; he just said we must be humble and tentative about our ability to know it. We are all partial knowers; all verbalizations are filled with biography, preference, genius, and past hurts. We are always invested in our knowing. We are all wading in Heraclitus’s ever-moving stream. This leads us to a necessary humility and to a very unsettling sense of the certitude that we all want and need. It seems we must somehow “kneel” to hear and see correctly. Polanyi said to his fellow scientists that the great geniuses had something more than detached, cold objectivity. They also had an ability “to dwell inside of things” that was more art than science, more poetry than prose, more spirit than rational control of the data. And more letting go than holding on.

Interestingly enough, this hard-core scientist taught an almost spiritual method that he called “indwelling” in order to get closer to truth. Geniuses, saints, inventors, discoverers, prophets, all truly creative people somehow have the “feel” for their area of giftedness. And it is almost impossible for them to know how they get that “feel.” That’s why they themselves know it is a gift (or in church language, a charism). We all know that some people say all the right words, but they still don’t have it. Yet what is “it”? Somehow you can be a scientist but not an artist. You can be a perfect technician but create nothing. You can be a functionary wearing the uniform, but the something that makes life happen is not there. We all know you can be a priest or bishop without having led a single person to God. The Enneagram was probably used for centuries to help spiritual directors train and refine the gift of “the reading of souls” and the transforming of people into who they are in God.

Polanyi concluded that it was necessary to “tune in” with intense personal involvement and even love of the situation and the other to be able to hear and see the situation truthfully. He said all truthful knowing had to acknowledge a tacit knowing (which is what religion means by faith, according to Polanyi), and this tacit knowing has something to do with trusting it, allowing it, believing in it and not starting with fear, suspicion, rejection. In other words, only those who love rightly see rightly! Only those who are situated correctly in the correct universe can read the situation with freedom and grandeur. Text plus full context equals genius. Only the true believer can trust that larger context, even to the point of including God. Then the believer is at a cosmic level of peacefulness: reality is good, the world is coherent, it is all going somewhere. That allows the believer to move ahead without a rejecting or superior attitude. Such people are constantly learning and always teachable and will likely do good things. A secular name for faith, I am sure. Eric Hoffer, the street philosopher, put it this way: “In times of great change [which is always], learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped for a world that no longer exists.” Faith itself, like the discernment of spirits, is actually a way to keep us learning, growing, and being transformed into God—not just a security blanket of doctrinal statements and moral principles. The Enneagram is much more demanding and much more dangerous than believing things. It is more about “unbelieving” the disguise that we all are. Ernest Becker called it “our vital lie.” Merton called it the false self. The Enneagram gets right to the point and calls it our sin.

I suspect Jesus was pointing to the same transformation in seeing and hearing when he said that it took “parables” to subvert our unconscious worldview—and thereby expose its illusions, even to us. Parables should make us a bit uncomfortable if we are really “hearing” them. If we fit them nicely into our business-as-usual world, parables have not served their purpose. A parable is supposed to change our operative world-view and unlock it from the inside—so that we can see and hear reality correctly. New and full context allows us to read text truthfully. All religions have tried to do the same thing with riddles and koans and mythic stories. Our whole universe has to be rearranged truthfully before individual teachings can be heard correctly. What we have done for centuries in the West is give people new moral and doctrinal teaching without rearranging their mythic worldview. It does not work. It leads nowhere new—or nowhere truly old for that matter. It creates legalists, ritualists, minimalists, and literalists, who always kill the spirit of a thing (except in mathematics). The Enneagram is not mathematics. It is the art of reading and transforming the soul into godly truth. The Enneagram, I would like to suggest, is a parabolic form of teaching. It subverts our unconscious and truly “mythical” worldview so that God can get in. That was the precise function of most of Jesus’ parables.

This subversive rearrangement of reality is called “conversion” and biblically has nothing to do with joining a denomination or accepting a new religious set of practices. I am personally convinced that this transfigured universe is the only thing that Jesus means by “the Truth.” This is the only Truth big enough to “set you free,” which any little doctrinal or moral certitudes about anything cannot do. If we are unwilling to live askew for a while, to be set off balance, to wait on the ever spacious threshold, we remain in the same old room for all our lives. If we will not balance knowing with a kind of open ended not knowing—nothing new seems to happen. Thus it is called “faith” and demands living with a certain degree of anxiety and holding a very real amount of tension.

We have to be trained how to do this. The only two things that are strong enough to accomplish this training are suffering and prayer. These two golden paths lead to a different shape of meaning, a different sized universe, a different set of securities and goals, and always a different Center. Only suffering and prayer are strong enough to decentralize both the ego and the superego. The practice of prayer we can choose to do ourselves; the suffering is done to us. But we have to be ready to learn from it when it happens and not waste time looking for someone to blame for our unnecessary suffering. That takes some good and strong teaching too. As I love to say on the road, “It is the things that you cannot do anything about and the things that you cannot do anything with that do something with you.” The Enneagram is just such a thing. It leads to both interior suffering and desperate prayer when we realize we cannot convert or transform ourselves.

When the first disciples of Jesus wanted to make the whole process into right rituals and right roles, and by implication right belief systems (common to all religion), Jesus told them, “You do not know what you are asking. Until you drink of the cup that I must drink, and be baptized with the baptism that I will be immersed in” (Mark 10:38), you basically do not know what I am talking about. You have nothing to say. It is not that we have a message and then suffer for it. It is much more the opposite: We suffer, come through it transformed, and then we have a message! This is the clear Jesus pattern and why he trained his disciples in the necessary path of suffering. There is something, it seems, that we can know in no other way. We hope to bypass such suffering by being moral, by being orthodox, by being ritualistic, but his words remain the same to us: “The cup that I must drink, you must also drink” (Mark 10:39). Enlightenment, conversion, seeing the truth is a journey of transformation, not membership in the right group or reciting the correct formulas or even practicing the right morality. As Paul made so clear both in his letters to the Romans and to the Galatians, law can give you correct information, but only God’s Spirit of love can transform you. It must have been a pretty important point to spend two letters of the New Testament in making it. He knew religion’s constant temptation to moralism, and he was one of those geniuses who had the bigger, but, oh, so subtle, truth.

We cannot be timid about this clear teaching of Jesus after centuries of Christians fighting over their formulations and rituals while unable or unwilling to see God in one another, in other races, in other religions, in the poor, in the earth, in the weak in every form. We cannot be timid about this clear teaching of Jesus after centuries of Christians unable to hear God in the pain of their enemies, in the suffering of the other, in the “paganism” of those whom they colonized and killed in the name of God. As Peter Dumitriu so perfectly said, “Jesus is always on the side of the crucified ones, and I believe he changes sides in the twinkling of an eye. He is not loyal to the person, or even less the group; Jesus is loyal to suffering.” If that is not the true “third way,” the true seeing, I do not know what it is. None of us want it, myself included. I would sooner be right about something. Back in control, back on top, smug, satisfied, and “saved.” Surely not changing sides to be with the pain. Yet, that is the only truth that will save us, and in this marvelous sense Jesus surely is the Savior of the world. No other path will get us through the accumulated suffering of history now. It is no surprise to me that the Enneagram is so distasteful to soft spirituality and even to individualistic spirituality. The Enneagram does not disguise the pain, the major surgery, or the price of enlightenment. By forcing us to face our own darkness, it soon leads us to address that same darkness as it shows itself in culture, oppression, injustice, and human degradation.

The voices of the ego will always be totally for or totally against because they are tiny and insecure voices. The voices of the superego will always sound like Mom, Dad, teachers, and church because they are archetypal, too large voices. But the sound of the Indwelling Voice, which many of us call the Holy Spirit, will invariably sound different, unpredictable, scarily new, and often with unexpected demands. To hear this Voice often feels like an obedience to another (obedio, to give ear to). If we are not trained in responding to others, if we are trapped inside of our own control issues, we will seldom be able to hear this Voice. Our supposed sense of conscience will be largely self-serving, and our sense of duty and religion will be the carping voice of the critical superego. Our hearing must get better, and there is much historical evidence that it is getting better: Human rights seem to finally have a chance on this earth. Human dignity has its protectors in every culture. But the protecting of human life, or any life, has not been impressive up to now, even in the church.

So how do we try to hear this Deeper Voice? When God speaks, it is first of all profoundly consoling and, as a result, demanding! Anybody who has walked long with God knows this. There are two utterly different forms of religion: one believes that God will love me if I change; the other believes that God loves me so that I can change! The first is the most common; the second follows upon an experience of personal Indwelling and personal love. Ideas inform us, but love forms us—in an intrinsic and lasting way. God is always willing to wait for the lasting transformations brought about by love. God must be very, very patient, surely with history but also with individuals. Most of us want results that are practical and immediate.

Here at the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, we are hoping to teach activists and doers this very important work of “discernment of spirits,” which is teaching on how to see and how to hear, how to subtly discern the patterns of good and evil. It seldom lends itself to simplistic “good guy/bad guy” thinking. Almost no one is prepared to teach us this except the churches, yet we ourselves fall into the much easier dualistic thinking. Robert Frost put it poetically: “The secret sits in the middle and knows, while others dance round in circles and suppose.” Our job is to teach people how to stay in the “middle” and wait for that “Third Something” called Gospel, a position that is always wiser and more healing than the usual alternatives of dualistic thinking. It is the space inside of which all transformation happens. Again and again we have found the Enneagram to be an amazing tool to lead people into such liminal space—where finally God can get at them. Because the imperial “I” is out of the way.

Our seeing and our hearing need to include, forgive, and reconcile what the rest of the world rejects, dismisses, and punishes. Now that is new! And that is also the ancient Enneagram. The New Zealand bishops call it moving “from retributive justice to restorative justice” in their 1996 pastoral letter. Such new thinking could rearrange our entire penal system, which is their reason for writing this letter, but it could also rearrange our pattern of human relationships. It was all contained in the biblical pattern of transformation, but up to now most of us just could not hear it, could not see it. God saves humanity not by punishing it but by restoring it! We overcome our evil not by a frontal and heroic attack, but by a humble letting go that always first feels like losing. Christianity is probably the only religion in the world that teaches us, from the very cross, how to win by losing. It is always a hard sell. Especially for folks who are into strength, domination, winning, and enforcing conclusions. God’s restorative justice is much more patient, and finally much more transformative, than mere coercive obedience.

The global issues of injustice, the culture of death that we are a part of, the sufferings of the oppressed, all of these demand that we bring the Voice of the Spirit to these well-denied and disguised situations, and not just our own tiny judgments or anger. This is the difference between true Gospel and mere political correctness or Band-Aid liberal responses. We are holding out for the greater Gospel, even though, I admit, it takes much longer, is often less efficient in the short run, demands much of us instead of others, and will always gather smaller constituencies. But in the end, as even Napoleon is supposed to have said, “We men of power merely rearrange the world, but it is only people of the Spirit who really change it.”

After almost thirty years of working with this gift, both with individuals and with groups, and now, with even greater confidence in its uncanny and surprising truth, I again offer the Enneagram as another of the endlessly brandished swords of the Holy Spirit. The Enneagram, like the Spirit of truth itself, will always set you free, but first it will make you miserable! So don’t bail out in the miserable stage, as many fearful church people do. Wait for the truth and freedom stage. As Mark’s Gospel so well puts it, first the “wild beasts” and only then “the angels” (Mark 1:13).

Part I

THE SLEEPING GIANT

A DYNAMIC TYPOLOGY

The Enneagram is a very old typology that describes nine different characters. It shares with many other typologies the crude reduction of human behavior to a limited number of character types.

Astrology connects its twelve types of human being to the particular constellation “under which” one is born. The Greek physician Hippocrates (d. 377 B.C.E.) traced his four temperaments (sanguinary, melancholic, choleric, phlegmatic) back to various “bodily fluids” (blood, black bile, bile, mucus). In the twentieth century Ernst Kretschmer (1888–1964) investigated the links between body build and the inclination to certain psychological troubles. He distinguished (1) pyknic (stocky), (2) leptosomatic (thin), and (3) athletic body types, and coordinated them with (1) cyclothymic (inclination to manic depressive illness), (2) schizothymic (inclination to schizophrenia), and (3) viscous (inclination to epilepsy) character features.

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) starts from the assumption that there are three pairs of functions that are expressed differently in each person: extroverted-introverted; sensate-intuitive; thinking-feeling. In each case everyone prefers one of the two possibilities; this results in eight possible combinations or types, e.g., the extroverted-intuitive thinker or the introverted-sensate feeler.

The American Isabel Briggs Myers discovered a further pair of functions (judging-perceiving: the inclination to quick, clear judgments and decisions as opposed to receptivity to many influences and kinds of information). Following Jung she developed the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a test that distinguishes among the sixteen types and is widely used in the United States, both in industry and the churches.1

Karen Horney (1885–1952) originally named three different ways that people try to overcome their fear of life: submission (turning to other persons); hostility (aggression against others); withdrawal (isolation from others). Later she developed a model pointing up four main ways by which people try to protect themselves from their fundamental anxiety: love, submissiveness, power, and distancing.

This last model matches to some extent the scheme worked out by the psychoanalyst Fritz Riemann (1902–79), who was influenced by astrology. He assumes four basic human fears: (1) fear of nearness, (2) fear of distance, (3) fear of change, (4) fear of permanence. This results in the four basic types: schizoid, depressive, compulsive, and hysterical.2

All these models try—under different presuppositions—to account for the experience that people are different, but that some individuals are surprisingly similar to one another. Each one of these typologies can be compared to a map that has the purpose of facilitating the overview of the realm of the human soul. Just as there are topographical, political, and street maps, so each of the typologies mentioned pursues a particular interest, and hence has its special strengths and weaknesses. None of them is all-inclusive. None of them is the thing itself. In the most popular of all typologies—the astrological—we have seriously to ask whether its presupposition, that there is a correspondence between the courses of the stars and the patterns of human destiny, is at all tenable. In any case, the study of a map never replaces the “experience” of the country itself.

All typologies have the disadvantage of necessarily neglecting the uniqueness, originality, and peculiar nature of the individual. There is no overlooking the danger of forcing oneself and others, for example, into the pigeonhole of a specific “sign” and in that way freezing the individual in place once and for all. The discovery of regular patterns in human behavior has meaning only when at the same time the possibility of change and liberation from the pressure of determinacy comes into view. This possibility, I believe, is opened up by the Enneagram.

The Enneagram is a very old map. Like other typologies, it describes different character types. But that is only the beginning. Beyond the description of conditions, the Enneagram contains an inner dynamic that aims at change. It demands a lot and is exhausting, at least when it is taught and carried out as originally intended. The Enneagram is more than an entertaining game for learning about oneself. It is concerned with change and making a turnaround, with what the religious traditions call conversion or repentance. It confronts us with compulsions and laws under which we live—usually without being aware of it—and it aims to invite us to go beyond them, to take steps into the domain of freedom.

The starting point of the Enneagram is the blind alleys into which we stumble in our attempt to protect our life from internal and external threats. The person, as created by God, is according to the Bible very good (Gen. 2:31). This human essence (one’s “true self”) is exposed to the assault of threatening forces even during pregnancy and at the latest from the moment of birth. The Christian doctrine of original sin points to this psychological fact by emphasizing that there actually is no undamaged, free, and “very good” person at any point of an individual’s existence. We are from the outset exposed to destructive powers and hence in need of redemption. Even the genetic material of which we are composed already contains programming that helps to shape our way of being from the moment of conception.

The external world meets the child first of all in the form of parents and siblings, and later though comrades, teachers, the values and norms of one’s group and religion, and whatever the general situation of society may be. Many different factors come together, stamp our inner life, and solidify into what in this book we call “voices.” These voices can usually be summarized in short and pregnant sentences. They accompany us—often unconsciously—all through our lives and have a definitive effect on our behavior and character. Sometimes these voices have been verbally communicated to us (“Always be nice and say thank you!”). Sometimes they have taken shape as a reaction to the nonverbal overall behavior of the environment (“Don’t come too close to me!”).

The growing person reacts to these voices by internalizing certain ideals (“I am good, if I. . . ”), by developing avoidance strategies to escape punishment or other unpleasant consequences of “misbehavior,” and by building up specific defense mechanisms. Guilt feelings always appear when one’s own ideal is not arrived at or fulfilled. By contrast, real misconduct, which is manifested in the Enneagram in the nine “root sins,” remains mostly hidden. Our “sins,” in fact, are the other side of our gift. They are the way we get our energy. They “work” for us. The Enneagram uncovers this false energy and enables us to look our real dilemma in the eye.

We start from the assumption that we are stamped at once by our inherited structures and by influences from our environment. More important than exploration of the causes (the question of “whence?”) is the question of the goal of our life (“whither?”). When Jesus and his disciples met the man born blind, the disciples asked Jesus: “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” Jesus answered: “It was not that this man sinned, or his parents, but that the works of God might be made manifest in him” (John 9:1–3). The Enneagram can help us develop an awareness for our future and destiny, for that true face that we do not yet “have,” but that already slumbers deep down inside us.

The Enneagram, from the Greek words ennea (=nine) and gramma (=sign or figure), is represented as a circle. On the circumference of the circle, there are nine points, each one forty degrees distant from the other, numbered clockwise from ONE to NINE, with NINE at twelve o’clock. Points THREE, SIX, and NINE are connected by a triangle; points TWO, FOUR, ONE, SEVEN, FIVE, EIGHT (and TWO) by an irregular six-pointed star. Each one of the Enneagram numbers refers to a certain state of energy; the transitions between the conditions are fluid. The connecting lines point to the dynamics between specific points of energy. But before we turn to detailed observations of these energies and their dynamics, we need some preliminary information, particularly on the history of how this symbol system originated.

Figure 1: The Enneagram

THE MYSTERY OF THE NUMBER 153

Until recently the origins of the Enneagram seemed to be hidden behind a veil. On the one hand, that made the subject especially mysterious; on the other, it nourished speculation and skepticism, and hardly contributed to the credibility of the system or even to a serious academic or scholarly evaluation of it. There were no known written sources from which one might have shown that it really was an “ancient wisdom teaching,” as most of the Enneagram’s adherents claimed. We too had to frankly acknowledge this deficit when our book appeared in 1989. At the outset the only thing known was that the Enneagram was first presented in the West by George Ivanovich Gurdjieff in 1916—and then as a comprehensive symbol of the harmonic structure and inner dynamism of the cosmos, not as a typology of character. Gurdjieff never gave explicit information about his sources. J. G. Bennett, one of Gurdjieff’s most prominent disciples, maintained that Gurdjieff had learned the Enneagram from Sufis in Asia. Oscar Ichazo, who in the early 1970s developed the “Enneagram of fixations,” used Gurdjieff’s model and in several statements—some of them highly cryptic—likewise referred to hidden Sufi sources, but also to his own visions of angels and similar things. That didn’t make the case any more conclusive or serious; and Ichazo too veiled his sources.

The common legend about how the Enneagram arose runs something like this: its origins go back many millennia to the Near East, the cradle of many of humanity’s great religions. This knowledge, which supposedly influenced all the major religions, was enriched by many of them and passed down through the ages. In this context Bennett makes special mention of the “Magi,” those Eastern wise men from the first millennium B.C.E., who were at once priests, philosophers, astronomers, astrologists, psychologists, theologians, and magicians. (According to the Gospel of Matthew such Magi came to Jerusalem after the birth of Jesus to adore the newborn Savior.)

Pythagoras too was initiated into the school of the Magi. The mathematician and spiritual master from Samos (ca. 569–496 B.C.E.) became a priest in his youth and spent long years in the religious centers of his time, especially in Egypt and Babylonia. Toward the end of his long life he founded a school of wisdom in southern Italy that was divided into “exoteric” and “esoteric” sections. The exoteric school taught life-wisdom for everyone; in the esoteric department the adepts were initiated into the secret connections of the cosmos, a subject on which they had to observe the strictest silence. In Pythagoras’s world picture, as in the later Jewish Cabbala, a crucial role was played by the numbers one to nine, with the number ten characterizing the cosmos as a whole. For Pythagoras these numbers had both a quantitative meaning as well as a qualitative, symbolic sense.

At this point there is a huge thousand-year gap in the legend. These, of course, were the centuries that saw the rise and fall of the Roman empire and the emergence of Christianity, first persecuted, but then established as the state religion.

After the coming of Islam (about a thousand years after Pythagoras), the earlier legend goes on to say, the old secret knowledge was preserved, developed, and passed on, in particular by a Sufi school. The Sufi masters, it was said, had never handed down the Enneagram as a whole, but revealed to individuals seeking counsel only those parts of it that were useful for a person’s spiritual growth. At any rate, in the whole body of Sufi literature there is not the faintest allusion to the Enneagram. This is explained, as a rule, by the fact that it was a secret knowledge, that was to be passed on exclusively by word of mouth.

In 1995 I, Andreas Ebert, stumbled on a text by the old Christian Desert Father Evagrius Ponticus that nonplussed me. Even though I didn’t understand all of it, I immediately had the sense that this text must have something to do with the Enneagram. Might this be the first and only written source pointing to the emergence of the Enneagram symbol? In January 1996 I published my discovery (“Are the Origins of the Enneagram Christian After All?”) in no. 11 of the Enneagram Monthly, an international journal. In April and May of 1996 the same journal carried a long essay by Lynn Quirolo (“Pythagoras, Gurdjieff and the Enneagram”), who had made the same discovery, independently of me, at the same time. Lynn Quirolo is a graduate of J. G. Bennett’s International Academy for Continuous Education in Sherborne (England). I am grateful to her article for some additional information, especially the decoding of the Pythagorean number symbolism (see below). The text that we had come across apparently contains essentially clearer hints about the origins of the Enneagram than all the earlier legends and speculations.3

So were the origins of the Enneagram Christian—and not Sufi—after all? The Jesuit Robert Ochs, one of the first Enneagram disciples of Claudio Naranjo, “was convinced that the Enneagram was profoundly rooted in Christian mysticism. . . . Ochs recognized the tradition of the Desert Fathers, a group of fourth-century monks who had developed the view of the seven deadly passions that charge the types with their energy.”4 In 1992 the German Benedictine Anselm Grün had also noted some astonishing parallels between the Enneagram and the teaching of the passions developed by Evagrius.5

The Desert Fathers, or “anchorites,” were a fourth-century movement. When, after long periods of persecution, the Christian church gradually became tolerated and finally even privileged and elevated to the state religion, the earnestness of the following of Christ slackened off everywhere. Opportunists pressed to be baptized. Soon the pagan temples were closed, and some “unconvertible” people were just as cruelly persecuted as the Christians had earlier been by the pagans. The new official church was extremely anxious about both pagan infiltration of its teaching and “heretical” (especially gnostic) tendencies. With the support of the state it pushed through its version of “orthodoxy.” Instead of a simple faith in Christ and a sincere readiness to suffer, the struggle for a dogmatic monopoly and social power and privileges came increasingly to the fore.

Countless individuals, both men and women, who wanted to be “serious” Christians, saw themselves compelled to retreat. They withdrew from the urban centers into the wilderness in order to live in small communities or hermitages. They renounced marriage, worldly goods, and secular activities, so as to find peace of heart (hesychia). The biography of the first great Desert Father, Anthony, which by the way was modeled on the story of Pythagoras, has continually inspired painters and other artists.

Life in the wilderness promoted an examination of the passions that overpowered the hermit, particularly in the form of fantasies and thoughts that had to be overcome—or “integrated,” as one might say in the language of present-day psychology.

Evagrius Ponticus was born in the year 345 in Ibora, in the province of Pontus (modern Georgia), the son of a bishop. At the age of thirty-four he was consecrated a deacon. In 381 he went to Constantinople, but he had to leave the city because of a love affair. After a stopover in Jerusalem he betook himself to Egypt to live there as a monk. Up until his death in 399 he remained in a hermitage in the Nitrian desert, where he composed his most important works. A particular intellectual influence on Evagrius came from the works of Origen, who was in turn influenced by Pythagorean thought and who championed the allegorical interpretation of the Bible (meaning that one read between the lines of biblical texts that were accessible to everyone, seeking for a mysterious, symbolical sense. Numerological speculation played a key role in this.) The Origenists were resisted and ultimately persecuted by the “anthropomorphists,” who allowed only literal exposition of the Bible.

In the year 399, shortly after Evagrius died, his partisans had to flee. They crossed the borders of the Roman Empire into Armenia and the Arab world, where they later influenced the Sufis. In Armenia Evagrius is widely venerated to this day; some of his writings have been preserved only in Armenian. The teachings of Evagrius and the Desert Fathers exerted, and continue to exert, an enormous influence, above all on Eastern Orthodox monks, for example on Mt. Athos—despite the persecutions and condemnations launched at them. At the Council of Jerusalem (553) Evagrius was condemned along with Origen. Three later councils repeated these condemnations.

The work of Evagrius closely coincides at two points with the Enneagram: in his Teaching on the Passions and in the description of a figure that is based on Pythagorean numerological speculation, which displays the essential features of the Enneagram symbol.

Evagrius developed a list of eight—or even nine, in one passage from the text De vitiis quae opposita sunt virtutibus (On the vices opposed to the virtues)—vices or distracting “thoughts” that impede the way to God and to passionless peace of heart. His point of departure was that strange saying of Jesus from Matthew 12:43–45: “When the unclean spirit has gone out of a man, he passes through waterless places seeking rest, but he finds none. Then he says, ‘I will return to my house from which I came,’ And when he comes he finds it empty, swept, and put in order. Then he goes and brings with him seven other spirits more evil than himself, and they enter and dwell there; and the last state of that man becomes worse than the first.” According to Evagrius the first evil spirit is “gluttony,” which eventually “incorporates” the seven other vices, so that the total is eight. The eight vices, then, are: anger (ONE in the Enneagram), pride (TWO), vanity or thirst for glory (THREE), sadness (in the sense of self-pity) or envy (FOUR), avarice (FIVE), gluttony (SEVEN), lust (EIGHT), and laziness or “acedia” (NINE). “Fear,” which is classified in the Enneagram as type SIX, is missing. Pope Gregory I later reduced this list to the one still in vogue today of the seven classical deadly sins, dropping vanity and sadness and leaving anger, pride, envy, greed, gluttony, lust, and sloth.

Even though Evagrius does mention nine vices in one passage, it’s still obvious that he did not systematize the vices as the “Enneagram of the fixations” that Oscar Ichazo developed in the 1970s. It seems rather that Evagrius understood a prototypical form of the Enneagram symbol in Gurdjieff’s sense as a symbol of the order and dynamism of the cosmos.

But now to the heart of the matter: toward the end of the Gospel according to John we are told how after his resurrection on Easter Jesus ordered his disciples to cast their fishing net into the Sea of Genesareth. They obeyed and caught 153 large fish. Why does the evangelist mention this number? John’s Gospel is full of enigmatic and ambiguous turns of phrase with “false bottoms.” Behind a flatly literal sense we again and again find deeper meanings. People—including Jesus’ disciples—interpret his words all too literally; and so curious misunderstandings