Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

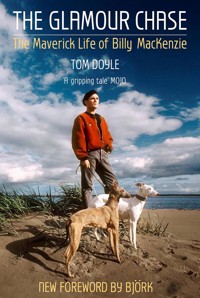

A first-rate charmer with a devilish twinkle in his eye, Billy MacKenzie was a maverick figure within the music industry whose wild and mischievous spirit possibly did him more harm than good. As frontman of the Associates, gifted with an otherwordly, octave-scaling operatic voice, MacKenzie, together with partner Alan Rankine, enjoyed Top Twenty chart success in 1982. At the height of their success, however, they split. Over the ensuing years, MacKenzie gained a reputation for his unhinged career tactics, generous spirit and knack for squandering large amounts of record-company money. Born in Dundee in 1957 he was the eldest son in a large Catholic family. He was bullied at school and sought refuge in music. He was a schemer and dreamer, a breeder of whippets and a bisexual who kept quiet about his private life. During his lifetime, his unique vocal gift attracted the attention of Shirley Bassey, Annie Lennox and Bjork. However, in the tradition of Scott Walker, Syd Barrett and Nick Drake, MacKenzie's tale is one of thwarted talent and, ultimately, tragedy. He was found dead, aged 39, at his father's home in Scotland, on 22 January 1997, having taken an overdose.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 500

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘That Billy MacKenzie lived an extraordinary life is beyond question . . . Doyle presents a character of excessive whims and creative frenzy . . . even if you’ve never heard an Associates’ record it’s essential reading. Simply, MacKenzie was a one-off’NME

‘A eulogy for pop’s great under-achiever . . . Tom Doyle’s shared Dundee upbringing not only allows a firm grip on MacKenzie’s motivation and insecurities . . . but the trust of the singer’s inner sanctum’Q

‘A stream of anecdotes – like the time MacKenzie booked a hotel room for his beloved whippets and charged it to his record company – make this a fitting memorial for a talent who was always a star, but knew that wasn’t really the point’GQ

‘This generous and affectionate profile tells a gripping tale . . . Ultimately, as Doyle points out [MacKenzie’s] loyalties lay with his extended family (of gypsy descent) and his whippets’MOJO

‘The Glamour Chase is a heroic attempt to prove that mainstream success via a sort of Krautrock cabaret noir and tortured artistry are not mutually incompatible. At the time of his suicide, Uncut likened the starsailing MacKenzie to Tim Buckley. Tom Doyle places him in the tradition of avant-Brits such as John Martyn or Robert Wyatt, or even Nick Drake . . . For Doyle, charting the highs and lows of this astonishing life became a magnificent obsession: he interviewed hundreds of people, scouring the streets of Dundee for clues . . . The Glamour Chase is insightful (Billy as precursor to the eclectatronic Björk?), its achievement two-fold: providing a fitting memoir for MacKenzie’s emotionally charged ‘popera’ and affording this pop era some much-needed credibility’UNCUT

‘MacKenzie . . . spent 39 years defying expectations, rejecting the conventional path to fame and revelling in a defiant wilfulness . . . [his] character emerges through a wealth of quotations, friends’ reminiscences, and incidents . . . Doyle’s book is a spirited attempt to convey some of the manic energy that made Billy MacKenzie such a deliriously driven artist’SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY

‘If ever there was a pop star who deserved a book written about him purely for his strength of personality it was Billy MacKenzie . . . It also does what all good books about music should as it sends you scurrying to dig out those old records and listen to that marvellous voice again’DUNDEE COURIER

‘MacKenzie lived his life with implausible relish, accompanied by his trademark octave-leaping vocal avalanche . . . Billy has a book that serves his memory well – extensively researched and overflowing with outrageous incident . . . Not bad going for the founder of the Dundee Whippet Rescue Society’ROY WILKINSON, SELECT

‘Even in your wildest dreams of decadent living and pop-star eccentricity, you just couldn’t make up a character as complex as Billy MacKenzie . . . [Doyle] weaves a glittering picture of a character that’s a gift to a biographer . . . as a warts-n-all account of a genuine one-off, The Glamour Chase . . . makes an unputdownable read about one of Scotland’s greatest almost-but-not-quite legends’HIGHLAND NEWS

‘Doyle clearly realises that little could be more colourful, fast paced and ultimately heart breaking than Billy’s relatively short life itself. And so he tells it straight . . . This is a rock biography of the highest calibre that manages to be both a hard headed look and a tribute to the late, great Billy MacKenzie’CLARE GRANT, DAILY RECORD

‘Billy MacKenzie was one of the greatest soul singers the late twentieth century produced, outstripping his peers by octaves . . . A good Billy MacKenzie song, like a good Scott Walker or Morrissey song, can make everything else in the world seem rather tiny and inconsequential’GAY TIMES

‘[Sulk] has a fair claim to the title of the most extraordinary album of the 1980s . . . as lavish and excessive and unique as the sessions that spawned it: a dense, luxurious, woozy wall of sound’ALEXIS PETRIDIS, THE GUARDIAN

‘Billy MacKenzie had the voice of an angel . . . given his prodigious multi-octave range, it was impossible to forget the Scottish vocalist. Indeed, “Party Fears Two”, “Club Country” and “18 Carat Love Affair” remain some of the most distinctive singles to come out of Britain in the early Eighties’PIERRE PERRONE, THE INDEPENDENT

The Glamour Chase

First published in Great Britain by Bloomsbury Publishing plc in 1998.

This revised edition published in 2011 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn LtdWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Tom Doyle 2011

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

ISBN 978 1 84697 209 6eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 061 6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by Hewer Text (UK) LtdPrinted and bound by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

Foreword by Björk

Foreword to first edition

Introduction

1 Vaulting the Fence

2 International Loner

3 Mental Torture

4 Plan 2

5 Tell Me Elephants Have Giraffe Necks

6 Orchestrated Chaos

7 Winding Up, Winding Down

8 The Sound of Barking

9 So Precious Is the Jagged Crown

10 The Dark Horse That Could Win the Race

11 From Fire to Ice

12 Cosmic Space Age Soul

13 Amused As Always

14 Before the Autumn Came

15 Close to a Violet Spark

16 Beyond the Sun

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Discography

Index

For Marjory Doyle

ForewordBjörk

My love affair with the Associates started when I was fifteen. There was only one record shop in Reykjavik that sold alternative music and I worked there with some of my mates. We didn’t care what was popular in England or America at the time. We just adopted the artists we liked and played them to death. I quite liked Fourth Drawer Down and The Affectionate Punch, but it was Sulk I really got into.

I was still looking for my identity as a singer and I really admired the way Billy used and manipulated his voice on that record. He was an incredibly spontaneous and intuitive singer – raw and dangerous. At the same time, he always sounded like he was really plugged into nature and the things surrounding him. I’ve heard people describe him as a white soul singer, but I’ve always thought his voice was more pagan and primitive, and for me that’s much more rare and interesting. There are hundreds of singers who sound a bit soulful, but there aren’t that many who sound like they have gypsy roots in them.

I thought ‘Party Fears Two’ was a bit too slick and over-produced at the time, but I listened to it again recently and I think it’s aged well. The electronics sound classic rather than clichéd and Billy’s voice really complements Alan Rankine’s arrangements.

I didn’t realise ‘Gloomy Sunday’ wasn’t one of their tunes until I was invited to do a benefit concert with Joni Mitchell in California in 1997. I turned up at the rehearsal and couldn’t believe it when the orchestra played this really straight jazz version without the outrageous key change in the middle. I tried protesting that they were missing out the best part of the song, then it dawned on me that the Associates’ version was obviously a cover. I was disappointed because the original isn’t half as challenging.

The Associates went there. They didn’t edit their nature out of it. They had pagan qualities. When I read this book about Billy MacKenzie, it said that all the lyrics were composed in the moment, not written down, like a stream of consciousness. For Medúlla, I thought about using Billy MacKenzie’s voice, and his father sent me old multi-tracks, the original tapes, and I wanted to work on it, celebrating voices, maybe do a duet with him. But when it came to it, I was too scared.

Foreword to first editionBono

The best aesthetes are working-class. Courage by contrast. Oscar Wilde on the buses, Versace down the chip shop, a falsetto voice on the terraces. Disco ball of nerves that he was, Billy MacKenzie was an aesthete. The Associates were a great group: we ripped them off. Billy was a great singer: I couldn’t rip him off. He was Caruso on a balloon of oxygen. He was over the top of the top and reminded me of my mate and similarly persecuted cabaret volcano, Gavin Friday.

There was a gang of us that seemed to start school on the same day: Billy, Ian, Julian, Pete and myself. Similar, except we couldn’t sing and Billy could. He had the opera . . . and when the world was brown or black or khaki and the raincoat was that year’s duffle, Billy was ultra violet, ultra bright, ultra everything except ultra cool. As I say, he had the opera. Others were singing from a lesser, more protected place. Some had the stance, even the craft, but never the generosity. We wanted to break your heart; he let his heart be broken.

The last time I saw him he looked like a cross between a bus conductor and Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront, except instead of a lowrider he had a whippet that seemed to take him for a walk. He was a fairground attraction. I think he’d been taken for a few rides too. He seemed surprised that I was so happy to see him and so excited to hear his voice on tape. He thought the world had forgotten him. I hope it never does.

Introduction

Mirroring the dramatic beauty of the bridges of the River Forth fifty-seven miles to the south, the view upon entering Dundee by either its road or rail bridge over the famously silver-grey waters of the Tay – particularly at night with its lights sparkling all the way up to the foot of the towering Law hill that provides its centrepiece – can be a stirring sight for even the cynical, seen-it-all traveller. In many ways, however, it provides a deceptively languid picture.

From the tail-end of the 1950s through to the dawning of the 70s, Dundee slowly began to expand, eventually more than doubling in size, as low-cost council housing began to eat up the miles of rolling countryside surrounding it. The tenement slum-clearance system that had proved so successful in other Scottish cities was deployed to full effect, with the working class systematically decanted to the outer-lying acres of pebbledash obscurity or oppressive, prison-like scatterings of whitewashed prefab blocks blueprinted in Scandinavia. While there was nothing staggeringly unusual about this expansion – most other towns and cities in the UK were undergoing similarly ill-advised modernization – it ensured that Dundee would remain the fourth largest concentration of population north of the border.

But, somehow, it had become neither one thing nor the other. A walk down the extremes of its High Street would take even an unhampered pensioner a less than exhausting ten minutes, while the long and winding bus journey from east to west boundary might swallow up more than an hour. In essence, Dundee had become too sprawling to remain a town, too modest in size to consider itself a city.

With every revolution this city/town attempted to make, there would always seem to be one cog missing, and its tired machinery would once again lumber to a halt. Even after decades of the boatyards and jute mills lying disused, when the council announced a move into the Thatcher-led focus upon soft industries in the 80s by building a technology park, for years the site remained as green and undisturbed as every other park in the vicinity. There are often grim statistics bandied about concerning Dundee which seem to come and go and then are forgotten by those in power: ‘HIV Capital of Scotland’ (although this honour sometimes shifts to Edinburgh); ‘Highest Number of Single Mothers Hooked on Heroin’ (ditto); ‘Second Only to Liverpool in Unemployment Figures’ (believable); and, most telling and best of all, ‘More Pubs Per Square Mile Than Anywhere in Europe’ (easily believable).

In fact, the last two figures make for an interesting combination come Friday and Saturday night, when the buses from the housing estates ferry legions of their younger natives, armed with their week’s wages or this fortnight’s dole money or other, more dubious profits, into the small concentration of the town centre. Its weekend nightlife is spirited, to say the least, if a bit too handy with its fists, given the mouthy, have-a-go attitude of a huge number of the inhabitants, a moment of misplaced eye contact being considered an invitation for any manner of physical attack. In some choice bars, the timing of the table-chucking, knuckle and tumbler kickoffs were easily more dependable than a cheap digital watch for an indication of the time.

Perhaps understandably, the thin brochure produced by the luckless Dundee Tourist Board in the 90s brushed over this notable aspect of the indigenous social habits. ‘If after all this [savouring of Dundee’s historical delights, the whaling museum etc., etc.], it’s just a quiet pint you’re after then you will be spoiled for choice,’ it states. ‘No matter where you go in Dundee you’ll find pubs, some peaceful, some busy and some with live music, but whatever one you choose it’s bound to be friendly.’ Until you have the hard neck to steal a glance at the wrong bloke’s pint, that is.

But that is to be overly dismissive of a city which has pockets of rough charm in an enviably picturesque setting. Seemingly every Dundonian generation has managed to spawn a thriving counter-culture of music and art, brimful of inspired nutters who somehow manage to pluck largely overlooked works and thoughts of wonder and ridiculousness out of the ether. Let us not forget that Dundee’s most famous artistic son was the nineteenth-century poet William McGonagall, remembered more for his enthusiasm than his talent and for the unintentional hilarity of his rambling poems. Along with the garrulous spirit inherent in much of the population, there is a tangential, pinballing thought process evident in many, along with a characteristically cruel, often brutal sense of humour.

And although this place of extremes would continually repel him before slowly drawing him back to it again, Billy MacKenzie – with his black and white contrasts and headful of magnificent obsessions and contradictions – in some ways seemed to embody Dundee.

To be honest, despite the fact that I lived in Dundee and had been obsessed with records virtually since birth, I’d never heard of Billy MacKenzie until 1982, when he was already a pop star and I was still fifteen. So if you’ll indulge me for a few pages while I write about Billy’s impact on Dundee and that greasy-haired fifteen-year-old, it will help to lift my personal reminiscences straight out of the picture and hopefully go some way towards proving that this isn’t a book written by a blinkered fan. That’s not to say I was never a blinkered fan, though.

I’d heard his name once before. Since the age of about thirteen, burying my head in the music papers – usually Sounds – had become one of my few self-abusive youthful habits, and it helped me to daydream away the thirty-minute Saturday morning bus journey (top deck, back row, fag) into town for my weekly flip through the record racks. It was that strange and – to me – exciting period in between punk and the ensuing atrocities of New Romantic. Around then, I remember casting an eye over a piece about some ‘new wave’ band called the Associates. Reading on, I was quietly surprised to find their singer reminiscing about his childhood and demented, alcohol-saturated parties in Fintry – weirdly enough, the area that the bus was currently passing through. I just forgot all about it again. That’s how it is when you’re thirteen.

Nearly two years later, there he was on Top of the Pops. The local paper was suddenly full of stories of the ‘Dundee Man Makes It Big’ variety. Now, to my knowledge, apart from some very lucky disco group a few years before, no one from Dundee had actually ever had a record in the charts, let alone one that sounded as if it was being beamed in from another remote, exotic planet. Everything about ‘Party Fears Two’ amazed me – the unnaturally wristy guitars, the classically tinged piano hook, and obviously, the voice, which sounded so otherworldly and original to my fairly naïve ears that it made my head swirl. This Billy MacKenzie from Fintry was snaking up and down what sounded like previously uncharted vocal scales, set to have musicologists scurrying off to rewrite the rule book. He didn’t even sound as if he was actually listening to the music. He might as well have had his Walkman on. What’s more, he was standing there on TV fronting this mutant musical offering with a huge, cheeky-bastard grin on his face – even watching himself on the monitors, just as other ‘normal’ people did if they ever got the chance to appear on the telly.

It turned out that back in Dundee he owned what in those days used to be called a ‘boutique’, on a hilly street that ran into the town, and so when I bought the Associates’ third album, Sulk, on the day of release, I handed it straight into Plan 2 to get it signed (just the sleeve, though; not the precious vinyl). A few days later, I went to pick it up from his sister, who was working there. Yeah, he’d done it, she said, though the biro obviously hadn’t been working at first, so it was a bit of an illegible scribble. But there it was: ‘To Tam, Love, Billy MacKenzie.’ Weirdly enough, although I’ve probably sold or lost hundreds of records over the years, I’ve still got it.

From then on, Billy’s existence in the town became my magical two-way link between dreary old Dundee and the world that lay beyond the Tay Bridge. When he appeared on Top of the Pops with ‘18 Carat Love Affair’ a few months later, cosmetic scars decorating his cheeks and upper arms, my mum came home and told me she’d heard that some bloke had glassed him in a local pub the weekend before. As I later found out, this actually might have been true, since Billy was beginning to attract unwelcome interest in the town on his frequent visits back home. But still, it was make-up for the performance, and Billy was clearly ripping the piss, on national TV, for all the thugs to see, confusing the issue magnificently. Throughout the summer of 1982, in all of the good ways and, without doubt, all of the sickeningly violent ways, Billy MacKenzie made Dundee buzz.

At this stage my Saturday nights would involve drinking and puffing sessions held in the front room of whichever mate’s parents had gone off down the social club (failing that, we’d find a derelict house and guzzle Super Lager like down-and-outs and smash all the remaining windows for a juvenile laugh), and then we’d make our way to Club Feet, Dundee’s trendiest club at the time, which opened its doors from seven till ten for the under-agers. A night out at the Club Feet usually involved fly imbibing of smuggled-in vodka and Coke and then – hey – it was on to the floor for stupid, rubbery dancing to records by the likes of Joy Division and Echo and the Bunnymen. Then one week the DJ announced in his impressive mid-Atlantic accent that the Associates’ Billy MacKenzie would be making a special appearance there the following week. The next week came. He didn’t show. The week after that, though, he did – swaggering through the door in beret and trench coat, his brother-in-law in tow for moral support, around half an hour before closing.

I’m now sort of ashamed to say it, but I pretty much instantly began to pummel him with relentless questions about London and his lyrics and other groups and blah-de-blah and just wouldn’t leave him alone to sign his autographs. The vodka fortifying my teenage cockiness, I even insisted upwards of a dozen times that I should definitely, no arguments, be the percussionist in the Associates. (I’d thought all this through and decided that the drum parts were too complicated.) He just laughed. And laughed. He was the first famous person I’d ever met, and although since then I’ve interviewed hundreds of them, many of them much more famous, the thrill is never the same. In my bladdered haze, I can even remember thinking he had Pop Star Teeth.

Then I grew up a bit, as you do. By the time I was seventeen or eighteen, Billy and I had a few mutual mates and I knew his brothers, so I’d often bump into him through one lot or the other. By then, the Associates Mark One had split up, Billy hadn’t had a hit since, and the stories I was hearing were often bitter accounts of how he’d sometimes turn those manipulative powers that made him such an important character in the London music industry on folk back in Dundee. Mostly it was just bitching and bad blood on their part (or his), but I became a bit more wary of him, I suppose.

He’d begun rehearsing a new band in Dundee and I’d sometimes be invited there by a couple of pals who were in the lineup. Although I didn’t exactly have a starry perception of Billy any more, it was still fascinating to watch him sing live (he hadn’t done it publicly since the hits and rumours abounded that his voice was the result of studio trickery), or suddenly shout, ‘Bring me my clarinets!’ in moments of comic frustration with the guitarists. I intently studied the intricate little head games he’d play with the musicians to get them to do what he wanted. One night we were up at Billy’s mum’s house when he’d just received the test pressing of Perhaps, and I was riveted by the disregard he had for his own record, the way that he scratched it to fuck with a clapped-out needle on a cheap music centre as he picked out different tracks. I’d begun interviewing bands by then and I would often ask them how they treated their own records. Most said they had mint copies because they never played them.

Then came the blur that is your late teens, and while I still loved almost everything the Associates did, they weren’t my main priority any more, although Billy’s presence on the scene in Dundee still proved illuminating; particularly one night in a cavernous church converted into a bar, where he talked me down when I was in the throes of a speed-induced panic attack (a horror I didn’t realize he’d had such first-hand experience of until I began researching this book). Another night he coolly introduced me to Matt Johnson of The The, whose records I loved, in the cocktail bar of the local club.

Every so often there would be wild parties at the MacKenzies’ father’s house in Bonnybank Road where people would dangle out of the windows and sit in the fish pond. Billy would stand in the packed living room and sing a cappella, while some watched on in hushed awe and others made derisory honking noises to try to put him off.

At the end of the 80s, I moved to London and ended up interviewing Billy for various magazines whenever he had a record coming out. But it was easy, even then, to see that he was growing less comfortable with his role.

On the release of his last proper Warners single, a lumpy reworking of Blondie’s ‘Heart Of Glass’ that was clearly the result of some hare-brained record company ploy to get him back in the charts, he made excuses about the record, insisting, ‘Oh, but it’s still the electronic stuff I’m into though, Tam. You know that.’ Then when he was subsequently dropped by the label, I interviewed him at length about the contractual palavers that had been involved. ‘At one point,’ he laughed, wearily, ‘they were going to sign me over to another label – like me going from Celtic to Liverpool with the transfer fee paying off my debts.’

From then on, Billy was mostly back up in Scotland, so I didn’t see much of him. Through a friend, I eventually learned that he’d moved down to London once more, and at an after-show party at a Sparks gig in ’94, I suddenly heard him shout my name through the crowd at the bar. There he was, new page-boy haircut on show, resident twinkle in his eye. I asked him where he was living.

‘Ach, Rotting Hill,’ he grimaced.

‘Love the hairdo, though, Billy,’ I said.

‘Aw, thanks,’ he offered back, grinning and brushing down his fringe. ‘It took ages to get it like this . . .’

We nattered away for a while and it was only after he’d gone that it dawned on me. Of course, Billy had always been receding badly, something that he was touchy about and blamed on a bad perm he’d once got in Edinburgh in his youth. The various hats had always concealed it. That night, he looked like some devilishly handsome indie pop star; Ian Brown’s charismatic big brother. With a great wig on.

The last time I saw Billy was in November 1996 at a party at the basement flat he was sharing with his new musical partner, Steve Aungle, in Holland Road, west London. Although his mother had died only a couple of months before and, as it later turned out, he’d been slightly nervous about hosting such a full-on soirée, he’d just signed a new deal with Nude Records and so at least there seemed to be something to celebrate. He’d shaved his hair and dyed it blond, with Perspex shades perched on his cranium for the full effect. He appeared to me to be on fine form, the usual Billy: all charm and compliments one minute, playfully argumentative the next. At one point he cupped his hand and rested it on the top of my head, saying nothing, just to see what I’d do. So I did nothing.

We talked about his new stuff (‘It’s what Bryan Ferry wishes he was doing,’ he bragged), about how it should do well since he was a bit of a music press darling (‘Yeah, but it’s no’ just about Q and the Melody Maker, is it?’ he baited me, knowing I’d been working for both). And then he quizzed me endlessly about the singer of a very well-known American band that I’d just interviewed, turning the tables on our first conversation when I was fifteen. I told him about how this rock star was incredibly affected in his every mannerism. When he walked in a room, he expected everyone to look at him.

‘Poor boy,’ Billy said, distractedly, gazing into space, standing in his own front room in a full-length fur coat.

At the end of the night, it was all hugs and see-you-soons, but that look has stayed with me ever since.

In the months of shock following Billy’s death, whenever I met anyone who’d known him, even casually, the unavoidable pall of sadness would soon give way to one funny story or another concerning his legendarily mischievous carrying-on. Eventually I realized that these were stories that shouldn’t be forgotten. Initially I was reluctant to write this book because it meant revisiting my own past as well as Billy’s and that can often be a nightmare. But hopefully my understanding of his background, as well as my years of profiling hundreds of subjects other than Billy MacKenzie, gives me a unique and sympathetic perspective on his story.

In the countless hours of research and interviews that have gone into this book, I learned that even if Billy was keen to litter his past with the half-truths and red herrings that he frequently used to tease and taunt music journalists, the real story was actually far more remarkable than the embellished version. If anything sounded too far-fetched, it would transpire that it really happened.

Given his unique vocal gift, unarguably incredible life story and doggedly determined struggles with the ‘oppressive’ record industry – long before anyone else thought to challenge its autocracy in the 1990s – Billy MacKenzie certainly deserves far, far more than just a footnote in the pop history of the less than glorious 80s.

1

Vaulting the Fence

It could all have been very different. In fact, there might have been no significant story at all, apart from a tragic paragraph in the Dundee Courier & Advertiser reporting that an infant had been run over and killed in a misadventurous road accident the day before.

Bursting with hyperactivity and a nervous, kinetic energy, as a young child Billy MacKenzie had begun to develop an alarming habit of running out into the street and straight into the path of an oncoming vehicle. On the most serious occasion, after sprinting into the twin-lane Victoria Road where his grandparents had successfully turned a trade in linen, buttons and pins into a busy second-hand goods shop, the knee-high Billy had tumbled over in the road and ended up trapped under the chassis of a car, seconds after the driver had skidded to a near cardiac-inducing halt. It was 1961, the boy was four, and perhaps mercifully, the burgeoning trend for compact, lightweight vehicle design enabled his father, James MacKenzie, to lever the car up by hand and free the errant youngster.

The MacKenzies were Calvinistic travelling stock, part of a Romany tradition that hawked its wares throughout Tayside and Angus and as far north as Aberdeenshire. But when the brood of Agnes MacKenzie, Billy’s grandmother, began to grow overwhelming, the family reluctantly decided to become what the north-eastern Scottish gypsies derisively nicknamed ‘toonies’: those who had forsaken the itinerant life to put down firmer roots.

There were six brothers – Davy, Willie, Sandy, Geordie, Jim, Ronnie – and one sister, Jean, who died as an infant, and as each grew to earning age, which in those postwar days often became a more appealing, or necessary, alternative to schooling even before a child had reached puberty, they were put to work in the shop. The MacKenzie sons were soon enjoying an unrivalled education in buying and selling that would earn them a lasting reputation as dealers in cheaply acquired used goods and furniture. Furthering their business efforts, the brothers began branching out into other premises. Headstrong and determined as the MacKenzie brothers were, a strong respect for blood bonding and a fierce sibling rivalry developed in their characters. Before long they were often in direct competition in their commercial exploits, and not above shaking one another down in their dealings. ‘We’d rob each other,’ Jim MacKenzie warmly remembers. ‘We’d always be at it, pulling wee strokes on each other . . .’

Although over the following decades, Jim MacKenzie would go on to control a small empire of second-hand shops, while his brothers diversified their interests to incorporate carpet warehouses and other properties, in the mid-50s he was widely known locally as a young man with a tough, formidable reputation and more disposable income than most stashed away in their back pocket. Because of that very nature, he was never entirely short of female attention. But it was to be Lily Agnes O’Phee Abbott who would turn his head. According to local accounts, she and her sister Betty, born of an Irish lineage that had escaped to the west coast of Scotland during the potato famine of 1846, were two of the more stunning additions to any dancehall.

In keeping with the era’s traditions of courtship and marrying young, the pair were soon wed in a Catholic ceremony in the town, Jim MacKenzie having embraced his wife’s religion. Before long, they had a son, William MacArthur MacKenzie, born on 27 March 1957, in Dundee Royal Infirmary.

Blessed with an uncommon maturity, even in his formative years, the young Billy MacKenzie displayed something of a gift for assessing the world around him and seeing it for all its wonder and absurdity. His father was often amazed by his child’s powers of playful manipulation. If Jim MacKenzie sent his son on an errand, he would later discover that Billy had somehow managed to coerce one of his other small friends into doing it, while he waited to collect the groceries, the change and the subsequent pat on the head for being such an obedient little lad. In tandem, he displayed extreme and unusual reactions, even in testing circumstances. Once, when he suffered a boyish accident that found him hobbling back to his parents with his big toenail hanging off, his father took him to a chiropodist to have the nail removed. Within the first seconds of the painful minor surgery, Billy began howling. But then Jim MacKenzie realized that his son wasn’t crying; he was laughing, hysterically and uncontrollably.

Billy later remembered this period of his childhood as being largely undisciplined, except for random moments of recrimination. ‘I had all the freedom in the world from the age of five onwards,’ he said. ‘I’d get up to all these terrible things and never get touched for it. Then I might just nick a biscuit or something and I’d get done in . . .’

Billy eagerly absorbed everything around him. He would sit for hours listening to his grandfather regaling him with tales of his travelling days, these romanticized yarns planting the seed of wanderlust in the attentive youngster’s mind. In fact, Billy later recollected a certain sense of frustration and boredom with being a child: ‘I was always dying to be an adult. I had ears like satellite dishes, picking up juicy titbits when they were around.’

Music, of course, was all around him. On his father’s side, the passion was for the gypsy camp-fire tradition and the fiddles and accordions of Scottish country dance music, although in the 50s a couple of Jim’s brothers had dabbled with guitar in country and western or rock ’n’ roll groups. On his mother’s side, jazz was the abiding love, and when allowed to stay up into the small hours at the frequent parties at home, Billy marvelled as his maternal grandmother, or his mother, held court with renditions of standards by Dinah Washington, Bessie Smith, Lena Horne and Billie Holiday. Remarkably, he would always claim that his granny could also blow a mean saxophone.

‘There was always singing about the house,’ Billy recalled. ‘If it wasn’t singing, it was fighting. If it wasn’t a torch song, it was a torch argument.’

Inevitably, Billy became the centre of attention at these lively gatherings, indulged for his strangely adult behaviour and endearing mischievousness. At three years of age, he would peer up his Auntie Betty’s skirt as she sang ‘The Little Boy That Santa Claus Forgot’. Then, much to his childish reluctance, eventually he would be coaxed by his revelling relatives into doing a turn. It was in this way that Billy first discovered his natural singing voice.

By the time he was eight he was mimicking Tom Jones and showcasing what was increasingly becoming an explosive, effortless vocal range. Before long, Billy was being invited to perform the lusty Welsh pop star’s songs, along with appropriately lewd pelvic grinds, for the old women who lived across the street, who would sit delicately dipping their biscuits into their tea as the young lad provided the entertainment. And although by nature a very unlikely cub scout, when Billy briefly joined the ranks of Lord Baden Powell’s militaristic youth movement, he shone during one of their annual performances, where he performed ‘Edelweiss’ from The Sound Of Music to the rows of quietly impressed parents. Recognizing that he might be on to something profitable, Billy brought his wilier ways into play. To earn extra pocket money, he would often sing Nat King Cole numbers for his mother and her friends and then run off with pocketfuls of spare change.

Even while at his primary school, St Mary’s Forebank, a strict Catholic establishment, Billy would duck and dodge the wrath of the nuns and priests and make amends for his seemingly untameable, boisterous behaviour by charming his tutors with his singing voice. Perhaps typically, however, once invited to join the school choir, he took advantage of having the loudest voice by attempting to throw the other choirboys off-key, since they were effectively following his lead. Having been taken under the wing of one teacher who recognized her pupil’s talents and even harboured designs on having him recommended to stage school, Billy was singled out for individual attention and taught to sing obscure Latin hymns and strange Russian folk songs. For a time, he would fantasize about joining the Vienna Boys’ Choir.

But it was the day-to-day transistor radio reality of pop music that completely enraptured him, in that transitional period where the old-fashioned crooners and the young, relatively long-haired bands began to jockey for position in the hit parade. The first singles to make any real impact on Billy were the jittery rock of the Rolling Stones’ ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ and Nancy and Frank Sinatra’s cutesy, dumb romantic duet ‘Somethin’ Stupid’.

Pop stardom first struck him as a hugely attractive career option when he watched some long-forgotten 60s band performing on Ready Steady Go while dangling in mid-air on pantomime safety wires. Every aspect of pop culture seemed designed to fascinate him. In this area he even began to idolize his mother and loved to watch her singing to herself in the mirror as she put on her false eyelashes before a night out. To him, she looked like Dusty Springfield.

But he later claimed that his pop star ambitions also stemmed from another, less selfish motive – he imagined that when he became famous he would be able to buy his Auntie Betty a new carpet to replace her threadbare Indian rug. ‘I just thought, Well, if you’re a pop star – like the ones I saw on the TV – you’re bound to be able to give things to people.’

With their potent mixture of Irish and gypsy blood, this generation of MacKenzies had now grown as expansive as the one that had gone before. Billy now had five younger brothers and sisters. First came his sister Lizzie, then his brother John, then sister Helen, followed by another two brothers, Alec and Jimmy. Growing up in Dundee could prove abrasive at times, and through their sheer numbers alone they learned how to handle themselves through their defence of one another, as well as developing a certain renown for unhinged exuberance. Before long, few dared to mess with the MacKenzie clan.

No less dramatically inclined than Billy, the brothers often played a game called ‘Teatime Theatre’ in which they would don headscarves and take turns wearing their father’s spare set of false teeth, while they mugged at themselves in the mirror. Billy once tried to describe the high-spirited nature of his family by saying, ‘Really we’re not that wild – just alive. We all like dancing and doing somersaults. If there’s a fence to climb, we’ll vault it.’

Now attending St Michael’s secondary school, Billy found his interests beginning to splinter into other, more athletic areas. Unbeknown to his parents, their son had become a decent footballer – although he would sometimes have to be sent off for joking around on the field – and an even better runner. One Saturday morning, Jim MacKenzie remembers, a teacher knocked on their front door to collect Billy, who was due to run for the Scottish Schoolboys sprinting team in a few hours, even though he had remained untypically quiet about the matter, perhaps as a result of being disquietened by the undue pressure. He triumphantly returned home later that evening with a bronze medal.

Since early childhood, Billy’s other abiding passion was for natural history and wildlife programmes on television, and he often talked of his ambition to become a vet. As a tearaway five-year-old, he first encountered what would become his spirit animal, after falling into the local Stobswell ponds and resurfacing to find an inquisitive whippet staring at him. He was instantly attracted to this smaller, sleeker breed of greyhound, and convinced the dog’s elderly owner to let him take it for walks after school. After she had agreed, Billy would devotedly trudge up to her small newsagents every evening, no matter how harsh the weather.

Billy’s subsequent lifelong obsession with whippets may often have appeared bizarre to outsiders, but in many ways he shared key characteristics with his chosen breed: let loose in the outside world, whippets often mindlessly tear around in every direction; indoors, they are incredibly docile, contentedly lazing away the hours. In unpublished diaries covering his entire history of owning whippets, Billy wrote of these first experiences with the borrowed dog back in the early 60s: ‘Armed with a Vimto and Bluebird toffee, we would head to the ponds, then over the playing fields where he would dive-bomb crows . . . it was the closest I’d get to watching a two-hundred metre final at the Olympics.’

Billy began slowly wearing his parents down with an unrelenting volley of requests for his own whippet. At first they dismissed it as a youthful fad, another example of a precociousness that would have him threatening to roll under a bus if his mother didn’t buy him a Ben Sherman shirt. But when, at twelve years old, Billy remained as unshakeably determined, they finally gave in. At the time, he and his best friend Alan Torrs would earn additional spending money by sweeping up and polishing the furniture in his father’s shops. When the pair were finishing up one June afternoon in 1969, Jim MacKenzie arrived and presented his visibly thrilled son with a pure-white, fawn-patched male dog that Billy decided to call Kim.

‘I couldn’t wait to get out into the country with him,’ he wrote, adding cheekily, ‘he hadn’t chased rabbits before, but he soon got the hang of it.’

In the often frustratingly fleeting Scottish summertime, particularly in the north-east, it was berry-picking season. Painfully early in the morning, rickety buses from the local farms called at prearranged points around the Dundee estates, where groups of cash-strapped casual workers were picked up and spent their days in the fields, pricking and scarring their hands as they plucked at the raspberry bushes, filling punnets and buckets weighed at a designated point and exchanged for handfuls of coins. The craftier berry pickers developed a habit of relieving themselves in the bucket, so in essence, they were being paid a few extra pence for their own urine. In the summer months the MacKenzie family often went to ‘the berries’ for additional cash, in the drills surrounding the local village of Blairgowrie. It was back-breaking, mind-numbing work which Billy hated. As an alternative to suffering this grim communal activity, he and Kim spent one summer staying with his granny at her cottage on the rural flatlands outside Dundee, a time which proved inspirational for Billy as he imagined himself living on the vast emptiness of the American prairies, although in the end the isolation began to get to him.

As is often the case with the rush of hormones and mess of teenage emotions, certain aspects of his daily life suddenly became a source of mild embarrassment for Billy, the most acute being his developing vocal talent. At the same time, his relationship with his father was becoming increasingly strained, particularly when Jim MacKenzie returned home from the pub with a handful of lightly pickled mates and insisted that they should witness his son’s remarkable singing voice. The sleeping fourteen-year-old Billy would be dragged from his bed – or when he got wiser to the situation, from a hiding position in a wardrobe – and reluctantly hauled downstairs for a wholly mortifying rendition of Nilsson’s 1972 hit ballad ‘Without You’, which was enjoying an extended occupation of the upper reaches of the charts that winter.

Although always coy and somewhat cagey about this period until much, much further on in his life, during this time Billy began to develop an even wilder, parentally uncontrollable streak, and later he would teasingly hint that his post-puberty had involved a string of ‘Cabaret-esque relationships’. At school he and Torrs – who shared his enthusiasm for dogs and the more unusual fringes of music – took no small pride in becoming slightly awkward social misfits who paraded around the playground with Mantovani records tucked under their arms. ‘We were the kind of cool ones,’ Billy claimed, ‘but we were singled out to be battered by the gangs from early on. I wasn’t a wimp, but I would have to map a route home every Friday night to avoid trouble.’

There were other problems. Billy was increasingly being ticked off by teachers for focusing his attention during classes on the acres of potential dog-walking terrain that lay beyond the school windows. It was around this time that he realized the very real benefits of an unusual talent that he had discovered as a child: projectile vomiting at will.

‘In class I’d say, “I’m feeling sick, sir,”’ he remembered. ‘They’d always say, “Shut up, MacKenzie”, because I was a bit of a troublemaker. Then I’d say, “I’m telling you . . . yaaargh” and throw up on my friend’s jumper so he’d have to go home as well, and we would go up in the hills with the dogs.’

Saving up from the proceeds of the part-time work for his father, Billy had secretly placed an advert in the ‘Wanted’ column of the local paper, looking for a whippet bitch. When a call came through from Aberdeen, he was forced to confess all to his parents who, instead of hitting the roof, appeared mutedly surprised by their son’s organizational capabilities, however covert. Often Kim would make some daring, Colditz-like escape from the MacKenzies’ home and trail Billy to school. Now, Honey, the gold fawn bitch would follow, and the two of them would hare around the school playing fields, much to the distraction of his classmates and the fury of the headmaster. Eventually a solution was found. Billy stopped going to school.

The first time Billy MacKenzie heard the sci-fi rock ’n’ roll of Roxy Music’s ‘Virginia Plain’, it nailed him to the wall. On opening one of the weekly music papers and finding the group’s saxophonist Andy MacKay pictured with a whippet, he became a slavish devotee of their music, joining their fan club. The first Roxy Music album, along with the stacked-heel stomp of the glam David Bowie and the frenzied vocal histrionics of Sparks, would become the sound-track to this period of his life. The radio was his only relief from the relentless tedium of work in the first months after he left school. At fifteen years of age he began a four-year apprenticeship with Scott’s Electricians in Dundee, an opening arranged as a favour to his father. Since Billy was generally to be found sorely lacking where manual labour or domestic chores were concerned, his tenure was fated to be short-lived from the beginning; it lasted just under twelve weeks.

However, around this time Billy was cajoled by his father into entering a talent night held at his local pub, with a first prize of £50. Although still well below the legal drinking age, he competed alongside a string of semi-professional club singers, his short repertoire consisting of bar-friendly interpretations of the Kinks’ ‘Sunny Afternoon’ and the Band’s ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’. To his own amazement, he won. ‘And that was the last I saw of Billy with the fifty quid that night,’ Jim MacKenzie states. ‘It was like, “See you later, Pop”, and he was gone.’

For the most part, Billy frittered away his days working with his father on the furniture-collecting van round, breeding his dogs – a first litter of six puppies were born at the foot of his bed as he slept – and attending whippet racing trials in nearby Forfar. But it was fast becoming clear that Billy’s life was lacking any real direction or future. What’s more, becoming increasingly individualistic, he had taken to dressing in 50s-style retro American clothing, while his peers were in tank tops and Oxford bags, and these exhibitionistic tendencies seemed to warrant unnecessary attention in Dundee in the early 70s. One night when Billy and Alan Torrs were walking through the town at night, the sixteen-year-olds were jumped by a gang and Alan’s cheek was slashed with a blade. If Billy had been toying with thoughts of escape before, this horrific incident seemed to strengthen his resolve. He was leaving Dundee.

‘I used to get ill at the thought of being trapped there,’ he once admitted. ‘Being in Scotland at that time was very claustrophobic and damaging. There was a very aggressive and oppressive attitude towards people like myself. I was getting beaten up too many times. When my best friend was cut up and carved and disfigured for life, I knew that I was next on the slab . . .’

2

International Loner

In an incident that would soon seep into American folklore, one winter night in 1967 Melvin Dummar, a plant worker from the small Nevada town of Gabbs, was driving the long distance home through the cold blackness of the desert, after an unsuccessful search for better-paid work in further-flung towns. Making a momentary pit-stop to take a leak, he heard the groans of what he initially assumed to be a down-and-out lying in the sand by the roadside. On realizing that the man was clearly injured as the result of a serious motorcycle crash, Dummar helped the injured wino into the passenger seat of his truck and offered to drive him to Las Vegas to seek medical attention. Initially the grey-bearded bum was reluctant, although realizing he had no other alternative but to accept the truck driver’s aid, he finally agreed.

During the long overnight journey that followed, Dummar made several attempts to engage the untalkative vagrant in some form of conversation. When enquiring as to his background and the circumstances leading up to his accident in the desert, the man made a passing claim to be the billionaire Howard Hughes. Dummar – not being familiar with the spectacularly eccentric history of the legendary Hollywood producer and aviation tycoon turned troubled recluse, and having some reasonable vision of billionaires being slightly more groomed than his unkempt passenger – dismissed the claim in his own mind as merely the delusions of an injured man.

Having effectively saved the old man’s life, early the next morning Dummar followed his passenger’s instructions and dropped him off behind the Sands Hotel on the Las Vegas Strip, at that time owned by Hughes. Handing the man what spare change he had in his pocket, no more than a handful of nickels and quarters, he drove off, giving the incident no further thought.

While the validity of this now-fabled tale has never been proven, it was to have no real effect on Melvin Dummar’s life until nearly ten years later. Not long after the incident in the desert, the terminally luckless Dummar split with his wife Veronica, in the wake of persistent money difficulties that had forced them to live in a trailer in Gabbs with their young daughter and become the serial victims of the repo men. Following a brief reconciliation only months later when Veronica announced that she was pregnant with the couple’s second child, the pair relocated to California, where Dummar found work as a milkman. But it was to be an ill-fated affair, and in the mid-70s the couple suffered an irreparable split. Within a year, however, Dummar’s fortunes would take a dramatic turn, earning him a lasting notoriety.

In April 1976 it was widely reported that Howard Hughes had died in Mexico at the age of seventy. At the time, Dummar was running a gas station in a back road of Willard, Utah, with his second wife, Bonnie, and this became the scene of a second, no less fantastical incident, later derided as the wild claims of an ambitious fraudster. A stranger, the account went, arrived at the gas station one spring afternoon and as Dummar was attending to his car, left an envelope on the desk in his office. The documents contained within, Dummar later claimed, appeared to be the handwritten last will and testament of Howard Hughes, listing the garage worker as the benefactor of one-sixteenth of the billionaire’s fortune, a sum calculated to be around $156 million.

Following the details of mysterious instructions attached to the will, Dummar surreptitiously dumped the documents into an in-tray at the reception of the offices of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Mormon Square, Salt Lake City, with a scribbled note declaring that the will had been found near the home of the founder of the Mormons, Joseph Smith, and that it should be brought to the attention of the president of the church. Examination of the document revealed that the document might feasibly be the work of Howard Hughes, and the will was filed in a Las Vegas county court. In a remarkable twist, it seemed that the pump attendant was now set to become a multimillionaire.

More bizarrely, however, for a brief period in the mid-70s, Billy MacKenzie’s life was to become interlinked with that of Melvin Dummar when, following a fateful chain of events, he became his brother-in-law.

In 1973, at the age of sixteen, Billy was torn between latent thoughts of studying to become a veterinary surgeon, a nagging instinct to somehow pursue the promise he’d shown as a sprinter and, of course, his growing unease with his environment and urge to desert it. Since the first option would inevitably involve him being forced to go back to St Michael’s to complete the Higher exams he’d skipped out on, this was instantly dismissed. Athletics, it seemed, was just as unlikely or impossible a career path as pop music. With no other reasonable alternative presenting itself, Billy began to search for potential escape routes, turning once more to his family, and in particular, the network of MacKenzie relatives dotted around the globe.

In the summer of that year, having sensibly weighed up his closest option as being the most appealing, Billy first experienced the scenic six-hour train journey that winds its way down Britain’s east coast from Dundee, through Edinburgh, Newcastle and York, to London’s King’s Cross station, and that was subsequently to become a well-worn track for him. At the time, his Auntie Betty – Lily MacKenzie’s sister – had moved down to the south London suburb of Clapham and ended up living in the same terrace as her brother Davey, who had agreed to share the responsibility of looking after their wandering nephew.

Clearly viewing this less as a holiday and more as a welcome opportunity of a permanent move to England, Billy used his unbridled energy and confidence to land himself a job as a junior sales assistant at the Scotch House – that corner of Regent Street that, until its closure in 2001, was forever Caledonia – where he spent the summer months selling kilts, expensive single-malt whisky and tartan travel blankets to mainly Japanese and American tourists. Keen to continue steering in the general direction of this new beacon on the horizon of his fortunes – no matter how dreary the daily reality of his work would prove at times – Billy would often be forced to bite his lip to avoid confrontations with the more difficult customers, but the blunt frankness and surface emotions of his upbringing were often difficult to suppress.

One day in the shop Billy was politely bantering with a Scottish expatriate, when the customer enquired after the geographical source of Billy’s accent and then made a glib comment that Dundee was ‘not exactly Scotland’. As Billy colourfully recalled later, ‘I honestly felt like stotting it right on him.’ Not long after, he quit the job, and suddenly experiencing the first pangs of homesickness, returned to Dundee.

Once he was back on that familiar terrain, however, his feelings of restlessness returned. A couple of years before, the MacKenzies had moved to a spacious house in the quiet, residential Bonnybank Road, near the centre of Dundee, becoming neighbours with their equally large mob of cousins on their Uncle Sandy’s side, and the two families had begun plotting a mass emigration to New Zealand. Only weeks before the planned departure, with the whole family having already gone through the painful vaccination programme that was a condition of their entry into the country, Jim MacKenzie suddenly changed his mind and backed out, leaving his relations to travel alone.

Having kept in contact with his cousins through occasional letters and phone calls, Billy soon found himself attracted to their enthusiastic descriptions of dramatic landscapes, exotic wildlife and bubbling hot springs. On the premise of it being an exploratory trip, Billy managed to coax from his father the price of a return plane ticket to New Zealand.

Armed with a photo album of family snapshots to offer some comfort in any pining moments, Billy was given a typically emotional send-off at the railway station by the MacKenzies. Despite his distinct lack of experience of the alien machinations of airports, and worse, discovering himself to be a white-knuckled flyer, thirty-six hours later he landed at Auckland airport, on the North Island. There he was met by his relatives and driven to the town of Ngaruawahia, where they had settled.

After finding work in Hamilton, some thirty miles to the south, Billy began to ease into his new life. The locals initially teased him about his strong accent and unusual appearance – the unfashionable 50s quiff not being common among young New Zealand farming stock in the 70s – although they soon learned that the boyish Scot himself possessed a savage tongue, and he came to earn their respect. More importantly, Billy was happy once again to be living closer to nature, the soul-stirring mountainscapes and rolling green countryside reminding him of Scotland, albeit with a more appealing climate.

Soon tiring of the exhausting routine that required rising in the early hours to catch the bus to Hamilton, Billy found a job in a local quarry. His daily working routine involved waiting at the quarry’s summit for the delivery lorries to dump their load of boulders into a huge mechanical vice, where he would pull the device’s starting handle. It was mindless, back-breaking work, often carried out in torrential rain, and not without danger. If the rocks refused to break up, Billy would be forced to clamber up to the top of the vice to rearrange the contents and run the risk of falling in. Then, one day, the foreman asked him to ferry the broken loads back down to the foot of the quarry in a truck. Billy had neglected to inform his employers that he didn’t own a driver’s licence – in fact, he had never even taken a lesson – and so, unsurprisingly, his first attempt to manoeuvre the truck very nearly killed him.

‘Driving on a steep slope at the quarry edge,’ he later wrote, ‘my foot slipped on the clutch and I was careering towards a four hundred foot drop. How he did it, I will never know, but the foreman sprinted towards me and managed to pull me off and away from the edge.’