9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

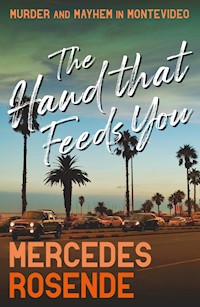

- Herausgeber: Bitter Lemon Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

The attempted robbery of the armoured car in the back streets of Montevideo is a miserable failure. A lucky break for the intrepid Ursula Lopez who manages to snatch all the loot, more hindered than helped by her faint-hearted and reluctant companion Diego. Only now, the wannabe robbers are hot on her heels. As is the police. And Ursula's sister. But Ursula turns out to be enormously talented when it comes to criminal undertakings, and given the hilarious ineptitude of those in pursuit, she might just pull it off.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Mercedes Rosende was born in 1958 in Montevideo, Uruguay. She is a lawyer and a journalist when not writing fiction. She has won many prizes for her novels and short stories. In 2005 she won the Premio Municipal de Narrativa for Demasiados blues, in 2008 the National Literature Prize for La muerte tendrá tus ojos and in 2019 the LiBeraturpreis in Germany for Crocodile Tears, the first in the Ursula López series published by Bitter Lemon Press. She lives in Ortigueira, La Coruña, Spain.

I keep an eye out for malice growinglike someone caring for a bonsai, which will dieif you leave it alone for just one day.My tiny tree of rage,my bloodless guillotine,the altarto the bad person we all are.In the dead calmthe echo of an eye for an eye lying in wait,misshapen body of resentment,crow perched on the branch of the funeral cypress,awaitingthe cruel, joyful moment when we’ll be at hand.

JOSÉ EMILIO PACHECO“The Tree of Malice”

Translation by Katherine Hedeen and Víctor Rodríguez Núñez

On 6 September 1971, 111 Tupamaro guerrillas escaped from Punta Carretas Prison, through a tunnel and without firing a single shot. It was one of the largest breakouts in history, and became known as El Abuso. The event occupied a prominent role in Uruguayan popular culture, on a par with Ernesto Che Guevara’s visit to the country in 1961, or the appearance of German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee in the Bay of Montevideo in 1939.

RAMIRO SANCHIZ, La Diaria

THE ESCAPE

Ursula doesn’t hesitate: she pushes Luz into the mouth of the tunnel. They leave behind them the brightly lit stores, the colourful clothes, the television sets, a world full of people. There is just the sound of piped music and the voices of the crowd. But the fear hasn’t disappeared. It clings to Ursula’s clothes, permeates her sweat, constricts her throat. It’s a strange fear, akin to vertigo, yet with a hint of forbidden pleasure.

The jaws of the tunnel close and the two women disappear into the most absolute darkness, the scene fades to black, the sound recedes. It’s hard to imagine, in this world of ours so full of stimuli.

Luz cried a little at first, a few tears cutting her cheeks, but she’s stopped now. Ursula has put the revolver back into the pink handbag squeezed tightly beneath her arm. She smells the earth, the soil, the damp roots, she smells the dust, the minerals, the iron and the clay.

Outside it is winter, a bright day, one of those days on which, with its heat and light, the sun tricks us into dreaming about spring, until we reach four in the afternoon.

They don’t talk much because they need to conserve their strength to keep moving forward, to keep making progress. They know it’s only fifty yards to the exit.

If they make it to the exit.

If the earth doesn’t devour them.