0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: E-BOOKARAMA

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

First published in 1898, "The Red Lily" is a novel by French author Anatole France that tells of the affair between a woman of the world, married to a politician, with an artist. A trip to Florence (which symbolizes the title) crowns this carnal and mystical union. Soon, jealousy insinuates itself into the lover's heart, who ends the affair.

Unique in its genre, "The Red Lily" is partially autobiographical, since it is based on the, at first passionate affair, between the author and Mrs. de Caillavet.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of contents

Preface

Chapter 1 - “I Need Love”

Chapter 2 - “One Can See that You are Young!”

Chapter 3 - A Discussion on the Little Corporal

Chapter 4 - The End of a Dream

Chapter 5 - A Dinner ‘En Famille’

Chapter 6 - A Distinguished Relict

Chapter 7 - Madame has Her Way

Chapter 8 - The Lady of the Bells

Chapter 9 - Choulette Finds a New Friend

Chapter 10 - Dechartre Arrives in Florence

Chapter 11 - “The Dawn of Faith and Love”

Chapter 12 - Hearts Awakened

Chapter 13 - “You Must Take Me with My Own Soul!”

Chapter 14 - The Avowal

Chapter 15 - The Mysterious Letter

Chapter 16 - “To-morrow?”

Chapter 17 - Miss Bell Asks a Question

Chapter 18 - “I Kiss Your Feet Because They have Come!”

Chapter 19 - Takes a Journey

Chapter 20 - What is Frankness?

Chapter 21 - “I Never have Loved Any One but You!”

Chapter 22 - A Meeting at the Station

Chapter 23 - “One is Never Kind when One is in Love”

Chapter 24 - Choulette’s Ambition

Chapter 25 - “We are Robbing Life”

Chapter 26 - In Dechartre’s Studio

Chapter 27 - The Primrose Path

Chapter 28 - News of Le Menil

Chapter 29 - Jealousy

Chapter 30 - A Letter from Robert

Chapter 31 - An Unwelcome Apparition

Chapter 32 - The Red Lily

Chapter 33 - A White Night

Chapter 34 - “I See the Other with You Always!”

THE RED LILY

Anatole France

Preface

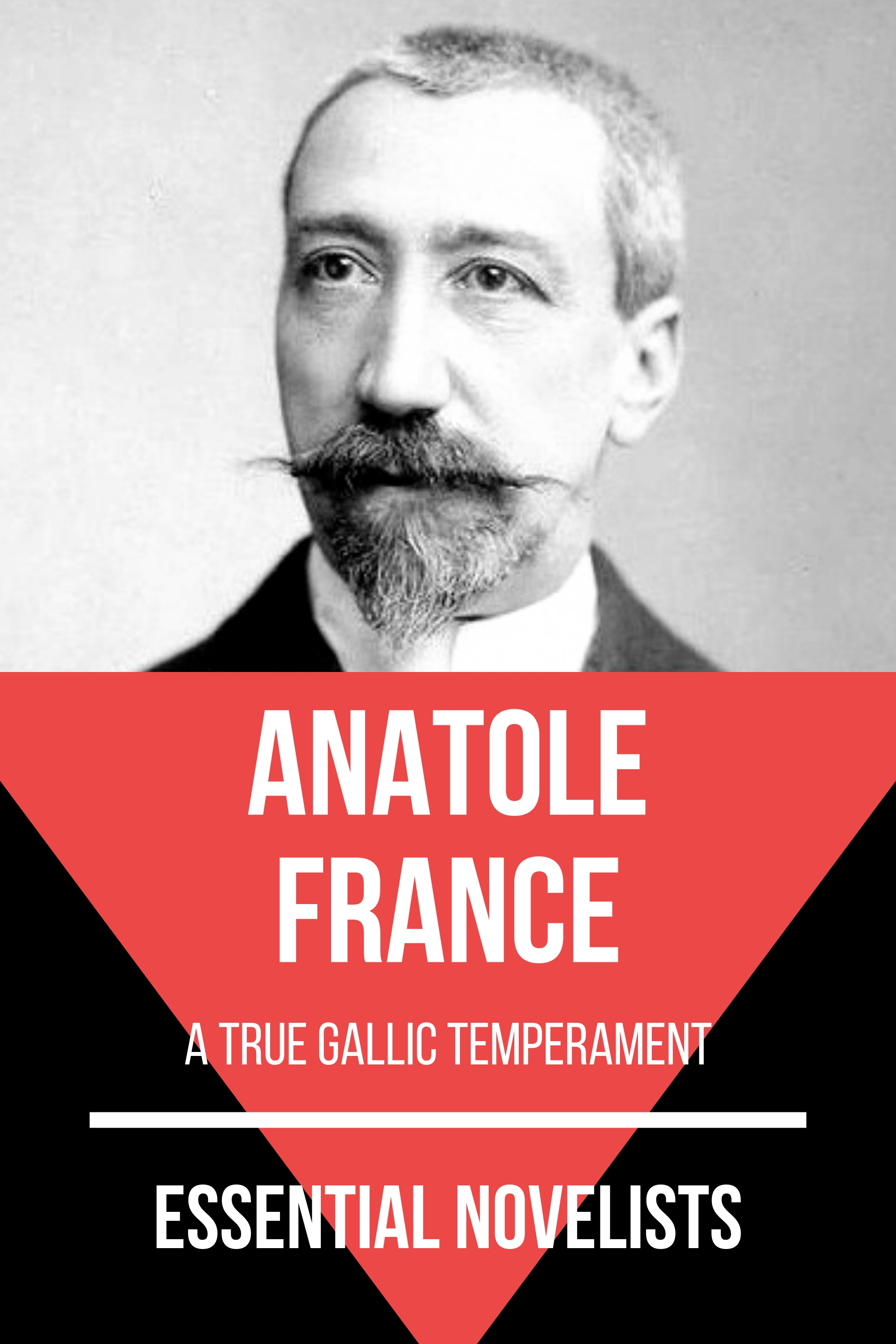

The real name of the subject of this preface is Jacques-Anatole Thibault. He was born in Paris, April 16, 1844, the son of a bookseller of the Quai Malaquais, in the shadow of the Institute. He was educated at the College Stanislas and published in 1868 an essay upon Alfred de Vigny. This was followed by two volumes of poetry: ‘Les Poemes Dores’ (1873), and ‘Les Noces Corinthiennes’ (1876). With the last mentioned book his reputation became established.

Anatole France belongs to the class of poets known as “Les Parnassiens.” Yet a book like ‘Les Noces Corinthiennes’ ought to be classified among a group of earlier lyrics, inasmuch as it shows to a large degree the influence of Andre Chenier and Alfred de Vigny. France was, and is, also a diligent contributor to many journals and reviews, among others, ‘Le Globe, Les Debats, Le Journal Officiel, L’Echo de Paris, La Revue de Famille, and Le Temps’. On the last mentioned journal he succeeded Jules Claretie. He is likewise Librarian to the Senate, and has been a member of the French Academy since 1896.

The above mentioned two volumes of poetry were followed by many works in prose, which we shall notice. France’s critical writings are collected in four volumes, under the title, ‘La Vie Litteraire’ (1888-1892); his political articles in ‘Opinions Sociales’ (2 vols., 1902). He combines in his style traces of Racine, Voltaire, Flaubert, and Renan, and, indeed, some of his novels, especially ‘Thais’ (1890), ‘Jerome Coignard’ (1893), and Lys Rouge (1894), which was crowned by the Academy, are romances of the first rank.

Criticism appears to Anatole France the most recent and possibly the ultimate evolution of literary expression, “admirably suited to a highly civilized society, rich in souvenirs and old traditions. . . . It proceeds,” in his opinion, “from philosophy and history, and demands for its development an absolute intellectual liberty. . . . . It is the last in date of all literary forms, and it will end by absorbing them all . . . . To be perfectly frank the critic should say: ‘Gentlemen, I propose to enlarge upon my own thoughts concerning Shakespeare, Racine, Pascal, Goethe, or any other writer.’”

It is hardly necessary to say much concerning a critic with such pronounced ideas as Anatole France. He gives us, indeed, the full flower of critical Renanism, but so individualized as to become perfection in grace, the extreme flowering of the Latin genius. It is not too much to say that the critical writings of Anatole France recall the Causeries du Lundi, the golden age of Sainte-Beuve!

As a writer of fiction, Anatole France made his debut in 1879 with ‘Jocaste’, and ‘Le Chat Maigre’. Success in this field was yet decidedly doubtful when ‘Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard’ appeared in 1881. It at once established his reputation; ‘Sylvestre Bonnard’, as ‘Le Lys Rouge’ later, was crowned by the French Academy. These novels are replete with fine irony, benevolent scepticism and piquant turns, and will survive the greater part of romances now read in France. The list of Anatole France’s works in fiction is a large one. The titles of nearly all of them, arranged in chronological order, are as follows: ‘Les Desirs de Jean Seyvien (1882); Abeille (1883); Le Livre de mon Ami (1885); Nos Enfants (1886); Balthazar (1889); Thais (1890); L’Etui de Naire (1892); Jerome Coignard, and La Rotisserie de la Reine Pedanque (1893); and Histoire Contemporaine (1897-1900), the latter consisting of four separate works: ‘L’Orme du Mail, Le Mannequin d’Osier, L’Anneau d’Amethyste, and Monsieur Bergeret a Paris’. All of his writings show his delicately critical analysis of passion, at first playfully tender in its irony, but later, under the influence of his critical antagonism to Brunetiere, growing keener, stronger, and more bitter. In ‘Thais’ he has undertaken to show the bond of sympathy that unites the pessimistic sceptic to the Christian ascetic, since both despise the world. In ‘Lys Rouge’, his greatest novel, he traces the perilously narrow line that separates love from hate; in ‘Opinions de M. l’Abbe Jerome Coignard’ he has given us the most radical breviary of scepticism that has appeared since Montaigne. ‘Le Livre de mon Ami’ is mostly autobiographical; ‘Clio’ (1900) contains historical sketches.

To represent Anatole France as one of the undying names in literature would hardly be extravagant. Not that I would endow Ariel with the stature and sinews of a Titan; this were to miss his distinctive qualities: delicacy, elegance, charm. He belongs to a category of writers who are more read and probably will ever exercise greater influence than some of greater name. The latter show us life as a whole; but life as a whole is too vast and too remote to excite in most of us more than a somewhat languid curiosity. France confines himself to themes of the keenest personal interest, the life of the world we live in. It is herein that he excels! His knowledge is wide, his sympathies are many-sided, his power of exposition is unsurpassed. No one has set before us the mind of our time, with its half-lights, its shadowy vistas, its indefiniteness, its haze on the horizon, so vividly as he.

In Octave Mirbeau’s notorious novel, a novel which it would be complimentary to describe as naturalistic, the heroine is warned by her director against the works of Anatole France, “Ne lisez jamais du Voltaire . . . C’est un peche mortel . . . ni de Renan . . . ni de l’Anatole France. Voila qui est dangereux.” The names are appropriately united; a real, if not precisely an apostolic, succession exists between the three writers.

JULES LEMAITRE

de l’Academie Francais

Chapter 1 - “I Need Love”

She gave a glance at the armchairs placed before the chimney, at the tea-table, which shone in the shade, and at the tall, pale stems of flowers ascending above Chinese vases. She thrust her hand among the flowery branches of the guelder roses to make their silvery balls quiver. Then she looked at herself in a mirror with serious attention. She held herself sidewise, her neck turned over her shoulder, to follow with her eyes the spring of her fine form in its sheath-like black satin gown, around which floated a light tunic studded with pearls wherein sombre lights scintillated. She went nearer, curious to know her face of that day. The mirror returned her look with tranquillity, as if this amiable woman whom she examined, and who was not unpleasing to her, lived without either acute joy or profound sadness.

On the walls of the large drawing-room, empty and silent, the figures of the tapestries, vague as shadows, showed pallid among their antique games and dying graces. Like them, the terra-cotta statuettes on slender columns, the groups of old Saxony, and the paintings of Sevres, spoke of past glories. On a pedestal ornamented with precious bronzes, the marble bust of some princess royal disguised as Diana appeared about to fly out of her turbulent drapery, while on the ceiling a figure of Night, powdered like a marquise and surrounded by cupids, sowed flowers. Everything was asleep, and only the crackling of the logs and the light rattle of Therese’s pearls could be heard.

Turning from the mirror, she lifted the corner of a curtain and saw through the window, beyond the dark trees of the quay, the Seine spreading its yellow reflections. Weariness of the sky and of the water was reflected in her fine gray eyes. The boat passed, the ‘Hirondelle’, emerging from an arch of the Alma Bridge, and carrying humble travellers toward Grenelle and Billancourt. She followed it with her eyes, then let the curtain fall, and, seating herself under the flowers, took a book from the table. On the straw-colored linen cover shone the title in gold: ‘Yseult la Blonde’, by Vivian Bell. It was a collection of French verses composed by an Englishwoman, and printed in London. She read indifferently, waiting for visitors, and thinking less of the poetry than of the poetess, Miss Bell, who was perhaps her most agreeable friend, and whom she almost never saw; who, at every one of their meetings, which were so rare, kissed her, calling her “darling,” and babbled; who, plain yet seductive, almost ridiculous, yet wholly exquisite, lived at Fiesole like a philosopher, while England celebrated her as her most beloved poet. Like Vernon Lee and like Mary Robinson, she had fallen in love with the life and art of Tuscany; and, without even finishing her Tristan, the first part of which had inspired in Burne-Jones dreamy aquarelles, she wrote Provencal verses and French poems expressing Italian ideas. She had sent her ‘Yseult la Blonde’ to “Darling,” with a letter inviting her to spend a month with her at Fiesole. She had written: “Come; you will see the most beautiful things in the world, and you will embellish them.”

And “darling” was saying to herself that she would not go, that she must remain in Paris. But the idea of seeing Miss Bell in Italy was not indifferent to her. And turning the leaves of the book, she stopped by chance at this line:

Love and gentle heart are one.

And she asked herself, with gentle irony, whether Miss Bell had ever been in love, and what manner of man could be the ideal of Miss Bell. The poetess had at Fiesole an escort, Prince Albertinelli. He was very handsome, but rather coarse and vulgar; too much so to please an aesthete who blended with the desire for love the mysticism of an Annunciation.

“Good-evening, Therese. I am positively worn out.”

The Princess Seniavine had entered, supple in her furs, which almost seemed to form a part of her dark beauty. She seated herself brusquely, and, in a voice at once harsh yet caressing, said:

“This morning I walked through the park with General Lariviere. I met him in an alley and made him go with me to the bridge, where he wished to buy from the guardian a learned magpie which performs the manual of arms with a gun. Oh! I am so tired!”

“But why did you drag the General to the bridge?”

“Because he had gout in his toe.”

Therese shrugged her shoulders, smiling:

“You squander your wickedness. You spoil things.”

“And you wish me, dear, to save my kindness and my wickedness for a serious investment?”

Therese made her drink some Tokay.

Preceded by the sound of his powerful breathing, General Lariviere approached with heavy state and sat between the two women, looking stubborn and self-satisfied, laughing in every wrinkle of his face.

“How is Monsieur Martin-Belleme? Always busy?”

Therese thought he was at the Chamber, and even that he was making a speech there.

Princess Seniavine, who was eating caviare sandwiches, asked Madame Martin why she had not gone to Madame Meillan’s the day before. They had played a comedy there.

“A Scandinavian play? Was it a success?”

“Yes — I don’t know. I was in the little green room, under the portrait of the Duc d’Orleans. Monsieur Le Menil came to me and did me one of those good turns that one never forgets. He saved me from Monsieur Garain.”

The General, who knew the Annual Register, and stored away all useful information, pricked up his ears.

“Garain,” he asked, “the minister who was in the Cabinet when the princes were exiled?”

“Himself. I was excessively agreeable to him. He talked to me of the yearnings of his heart and he looked at me with alarming tenderness. And from time to time he gazed, with sighs, at the portrait of the Duc d’Orleans. I said to him: ‘Monsieur Garain, you are making a mistake. It is my sister-in-law who is an Orleanist. I am not.’ At this moment Monsieur Le Menil came to escort me to the buffet. He paid great compliments — to my horses! He said, also, there was nothing so beautiful as the forest in winter. He talked about wolves. That refreshed me.”

The General, who did not like young men, said he had met Le Menil the day before in the forest, galloping, with vast space between himself and his saddle.

He declared that old cavaliers alone retained the traditions of good horsemanship; that people in society now rode like jockeys.

“It is the same with fencing,” he added. “Formerly —”

Princess Seniavine interrupted him:

“General, look and see how charming Madame Martin is. She is always charming, but at this moment she is prettier than ever. It is because she is bored. Nothing becomes her better than to be bored. Since we have been here, we have bored her terribly. Look at her: her forehead clouded, her glance vague, her mouth dolorous. Behold a victim!”

She arose, kissed Therese tumultuously, and fled, leaving the General astonished.

Madame Martin-Belleme prayed him not to listen to what the Princess had said.

He collected himself and asked:

“And how are your poets, Madame?”

It was difficult for him to forgive Madame Martin her preference for people who lived by writing and were not of his circle.

“Yes, your poets. What has become of that Monsieur Choulette, who visits you wrapped in a red muffler?”

“My poets? They forget me, they abandon me. One should not rely on anybody. Men and women — nothing is sure. Life is a continual betrayal. Only that poor Miss Bell does not forget me. She has written to me from Florence and sent her book.”

“Miss Bell? Isn’t she that young person who looks, with her yellow waving hair, like a little lapdog?”

He reflected, and expressed the opinion that she must be at least thirty.

An old lady, wearing with modest dignity her crown of white hair, and a little vivacious man with shrewd eyes, came in suddenly — Madame Marmet and M. Paul Vence. Then, carrying himself very stiffly, with a square monocle in his eye, appeared M. Daniel Salomon, the arbiter of elegance. The General hurried out.

They talked of the novel of the week. Madame Marmet had dined often with the author, a young and very amiable man. Paul Vence thought the book tiresome.

“Oh,” sighed Madame Martin, “all books are tiresome. But men are more tiresome than books, and they are more exacting.”

Madame Marmet said that her husband, who had much literary taste, had retained, until the end of his days, a horror of naturalism. She was the widow of a member of the ‘Academie des Inscriptions’, and plumed herself upon her illustrious widowhood. She was sweet and modest in her black gown and her beautiful white hair.

Madame Martin said to M. Daniel Salomon that she wished to consult him particularly on the picture of a group of beautiful children.

“You will tell me if it pleases you. You may also give me your opinion, Monsieur Vence, unless you disdain such trifles.”

M. Daniel Salomon looked at Paul Vence through his monocle with disdain. Paul Vence surveyed the drawing-room.

“You have beautiful things, Madame. That would be nothing. But you have only beautiful things, and all serve to set off your own beauty.”

She did not conceal her pleasure at hearing him speak in that way. She regarded Paul Vence as the only really intelligent man she knew. She had appreciated him before his books had made him celebrated. His ill-health, his dark humor, his assiduous labor, separated him from society. The little bilious man was not very pleasing; yet he attracted her. She held in high esteem his profound irony, his great pride, his talent ripened in solitude, and she admired him, with reason, as an excellent writer, the author of powerful essays on art and on life.

Little by little the room filled with a brilliant crowd. Within the large circle of armchairs were Madame de Wesson, about whom people told frightful stories, and who kept, after twenty years of half-smothered scandal, the eyes of a child and cheeks of virginal smoothness; old Madame de Morlaine, who shouted her witty phrases in piercing cries; Madame Raymond, the wife of the Academician; Madame Garain, the wife of the exminister; three other ladies; and, standing easily against the mantelpiece, M. Berthier d’Eyzelles, editor of the ‘Journal des Debats’, a deputy who caressed his white beard while Madame de Morlaine shouted at him:

“Your article on bimetallism is a pearl, a jewel! Especially the end of it.”

Standing in the rear of the room, young clubmen, very grave, lisped among themselves:

“What did he do to get the button from the Prince?”

“He, nothing. His wife, everything.”

They had their own cynical philosophy. One of them had no faith in promises of men.

“They are types that do not suit me. They wear their hearts on their hands and on their mouths. You present yourself for admission to a club. They say, ‘I promise to give you a white ball. It will be an alabaster ball — a snowball! They vote. It’s a black ball. Life seems a vile affair when I think of it.”

“Then don’t think of it.”

Daniel Salomon, who had joined them, whispered in their ears spicy stories in a lowered voice. And at every strange revelation concerning Madame Raymond, or Madame Berthier, or Princess Seniavine, he added, negligently:

“Everybody knows it.”

Then, little by little, the crowd of visitors dispersed. Only Madame Marmet and Paul Vence remained.

The latter went toward Madame Martin, and asked:

“When do you wish me to introduce Dechartre to you?”

It was the second time he had asked this of her. She did not like to see new faces. She replied, unconcernedly:

“Your sculptor? When you wish. I saw at the Champ de Mars medallions made by him which are very good. But he does not work much. He is an amateur, is he not?”

“He is a delicate artist. He does not need to work in order to live. He caresses his figures with loving slowness. But do not be deceived about him, Madame. He knows and he feels. He would be a master if he did not live alone. I have known him since his childhood. People think that he is solitary and morose. He is passionate and timid. What he lacks, what he will lack always to reach the highest point of his art, is simplicity of mind. He is restless, and he spoils his most beautiful impressions. In my opinion he was created less for sculpture than for poetry or philosophy. He knows a great deal, and you will be astonished at the wealth of his mind.”

Madame Marmet approved.

She pleased society by appearing to find pleasure in it. She listened a great deal and talked little. Very affable, she gave value to her affability by not squandering it. Either because she liked Madame Martin, or because she knew how to give discreet marks of preference in every house she went, she warmed herself contentedly, like a relative, in a corner of the Louis XVI chimney, which suited her beauty. She lacked only her dog.

“How is Toby?” asked Madame Martin. “Monsieur Vence, do you know Toby? He has long silky hair and a lovely little black nose.”

Madame Marmet was relishing the praise of Toby, when an old man, pink and blond, with curly hair, short-sighted, almost blind under his golden spectacles, rather short, striking against the furniture, bowing to empty armchairs, blundering into the mirrors, pushed his crooked nose before Madame Marmet, who looked at him indignantly.

It was M. Schmoll, member of the Academie des Inscriptions. He smiled and turned a madrigal for the Countess Martin with that hereditary harsh, coarse voice with which the Jews, his fathers, pressed their creditors, the peasants of Alsace, of Poland, and of the Crimea. He dragged his phrases heavily. This great philologist knew all languages except French. And Madame Martin enjoyed his affable phrases, heavy and rusty like the iron-work of brica-brac shops, among which fell dried leaves of anthology. M. Schmoll liked poets and women, and had wit.

Madame Marmet feigned not to know him, and went out without returning his bow.

When he had exhausted his pretty madrigals, M. Schmoll became sombre and pitiful. He complained piteously. He was not decorated enough, not provided with sinecures enough, nor well fed enough by the State — he, Madame Schmoll, and their five daughters. His lamentations had some grandeur. Something of the soul of Ezekiel and of Jeremiah was in them.

Unfortunately, turning his golden-spectacled eyes toward the table, he discovered Vivian Bell’s book.

“Oh, ‘Yseult La Blonde’,” he exclaimed, bitterly. “You are reading that book, Madame? Well, learn that Mademoiselle Vivian Bell has stolen an inscription from me, and that she has altered it, moreover, by putting it into verse. You will find it on page 109 of her book: ‘A shade may weep over a shade.’ You hear, Madame? ‘A shade may weep over a shade.’ Well, those words are translated literally from a funeral inscription which I was the first to publish and to illustrate. Last year, one day, when I was dining at your house, being placed by the side of Mademoiselle Bell, I quoted this phrase to her, and it pleased her a great deal. At her request, the next day I translated into French the entire inscription and sent it to her. And now I find it changed in this volume of verses under this title: ‘On the Sacred Way’— the sacred way, that is I.”

And he repeated, in his bad humor:

“I, Madame, am the sacred way.”

He was annoyed that the poet had not spoken to him about this inscription. He would have liked to see his name at the top of the poem, in the verses, in the rhymes. He wished to see his name everywhere, and always looked for it in the journals with which his pockets were stuffed. But he had no rancor. He was not really angry with Miss Bell. He admitted gracefully that she was a distinguished person, and a poet that did great honor to England.

When he had gone, the Countess Martin asked ingenuously of Paul Vence if he knew why that good Madame Marmet had looked at M. Schmoll with such marked though silent anger. He was surprised that she did not know.

“I never know anything,” she said.

“But the quarrel between Schmoll and Marmet is famous. It ceased only at the death of Marmet.

“The day that poor Marmet was buried, snow was falling. We were wet and frozen to the bones. At the grave, in the wind, in the mud, Schmoll read under his umbrella a speech full of jovial cruelty and triumphant pity, which he took afterward to the newspapers in a mourning carriage. An indiscreet friend let Madame Marmet hear of it, and she fainted. Is it possible, Madame, that you have not heard of this learned and ferocious quarrel?

“The Etruscan language was the cause of it. Marmet made it his unique study. He was surnamed Marmet the Etruscan. Neither he nor any one else knew a word of that language, the last vestige of which is lost. Schmoll said continually to Marmet: ‘You do not know Etruscan, my dear colleague; that is the reason why you are an honorable savant and a fair-minded man.’ Piqued by his ironic praise, Marmet thought of learning a little Etruscan. He read to his colleague a memoir on the part played by flexions in the idiom of the ancient Tuscans.”

Madame Martin asked what a flexion was.

“Oh, Madame, if I explain anything to you, it will mix up everything. Be content with knowing that in that memoir poor Marmet quoted Latin texts and quoted them wrong. Schmoll is a Latinist of great learning, and, after Mommsen, the chief epigraphist of the world.

“He reproached his young colleague — Marmet was not fifty years old — with reading Etruscan too well and Latin not well enough. From that time Marmet had no rest. At every meeting he was mocked unmercifully; and, finally, in spite of his softness, he got angry. Schmoll is without rancor. It is a virtue of his race. He does not bear ill-will to those whom he persecutes. One day, as he went up the stairway of the Institute with Renan and Oppert, he met Marmet, and extended his hand to him. Marmet refused to take it, and said ‘I do not know you.’—‘Do you take me for a Latin inscription?’ Schmoll replied. Marmet died and was buried because of that satire. Now you know the reason why his widow sees his enemy with horror.”

“And I have made them dine together, side by side.”

“Madame, it was not immoral, but it was cruel.”

“My dear sir, I shall shock you, perhaps; but if I had to choose, I should like better to do an immoral thing than a cruel one.”

A young man, tall, thin, dark, with a long moustache, entered, and bowed with brusque suppleness.

“Monsieur Vence, I think that you know Monsieur Le Menil.”

They had met before at Madame Martin’s, and saw each other often at the Fencing Club. The day before they had met at Madame Meillan’s .

“Madame Meillan’s — there’s a house where one is bored,” said Paul Vence.

“Yet Academicians go there,” said M. Robert Le Menil. “I do not exaggerate their value, but they are the elite.”

Madame Martin smiled.

“We know, Monsieur Le Menil, that at Madame Meillan’s you are preoccupied by the women more than by the Academicians. You escorted Princess Seniavine to the buffet and talked to her about wolves.”

“What wolves?”

“Wolves, and forests blackened by winter. We thought that with so pretty a woman your conversation was rather savage!”

Paul Vence rose.

“So you permit, Madame, that I should bring my friend Dechartre? He has a great desire to know you, and I hope he will not displease you. There is life in his mind. He is full of ideas.”

“Oh, I do not ask for so much,” Madame Martin said. “People that are natural and show themselves as they are rarely bore me, and sometimes they amuse me.”

When Paul Vence had gone, Le Menil listened until the noise of footsteps had vanished; then, coming nearer:

“To-morrow, at three o’clock? Do you still love me?”

He asked her to reply while they were alone. She answered that it was late, that she expected no more visitors, and that no one except her husband would come.

He entreated. Then she said:

“I shall be free to-morrow all day. Wait for me at three o’clock.”

He thanked her with a look. Then, placing himself on at the other side of the chimney, he asked who was that Dechartre whom she wished introduced to her.

“I do not wish him to be introduced to me. He is to be introduced to me. He is a sculptor.”

He deplored the fact that she needed to see new faces, adding:

“A sculptor? They are usually brutal.”

“Oh, but this one does so little sculpture! But if it annoys you that I should meet him, I will not do so.”

“I should be sorry if society took any part of the time you might give to me.”

“My friend, you can not complain of that. I did not even go to Madame Meillan’s yesterday.”

“You are right to show yourself there as little as possible. It is not a house for you.”

He explained. All the women that went there had had some spicy adventure which was known and talked about. Besides, Madame Meillan favored intrigue. He gave examples. Madame Martin, however, her hands extended on the arms of the chair in charming restfulness, her head inclined, looked at the dying embers in the grate. Her thoughtful mood had flown. Nothing of it remained on her face, a little saddened, nor in her languid body, more desirable than ever in the quiescence of her mind. She kept for a while a profound immobility, which added to her personal attraction the charm of things that art had created.

He asked her of what she was thinking. Escaping the magic of the blaze in the ashes, she said:

“We will go to-morrow, if you wish, to far distant places, to the odd districts where the poor people live. I like the old streets where misery dwells.”

He promised to satisfy her taste, although he let her know that he thought it absurd. The walks that she led him sometimes bored him, and he thought them dangerous. People might see them.

“And since we have been successful until now in not causing gossip —”

She shook her head.

“Do you think that people have not talked about us? Whether they know or do not know, they talk. Not everything is known, but everything is said.”

She relapsed into her dream. He thought her discontented, cross, for some reason which she would not tell. He bent upon her beautiful, grave eyes which reflected the light of the grate. But she reassured him.

“I do not know whether any one talks about me. And what do I care? Nothing matters.”

He left her. He was going to dine at the club, where a friend was waiting for him. She followed him with her eyes, with peaceful sympathy. Then she began again to read in the ashes.

She saw in them the days of her childhood; the castle wherein she had passed the sweet, sad summers; the dark and humid park; the pond where slept the green water; the marble nymphs under the chestnut-trees, and the bench on which she had wept and desired death. To-day she still ignored the cause of her youthful despair, when the ardent awakening of her imagination threw her into a troubled maze of desires and of fears. When she was a child, life frightened her. And now she knew that life is not worth so much anxiety nor so much hope; that it is a very ordinary thing. She should have known this. She thought:

“I saw mamma; she was good, very simple, and not very happy. I dreamed of a destiny different from hers. Why? I felt around me the insipid taste of life, and seemed to inhale the future like a salt and pungent aroma. Why? What did I want, and what did I expect? Was I not warned enough of the sadness of everything?”

She had been born rich, in the brilliancy of a fortune too new. She was a daughter of that Montessuy, who, at first a clerk in a Parisian bank, founded and governed two great establishments, brought to sustain them the resources of a brilliant mind, invincible force of character, a rare alliance of cleverness and honesty, and treated with the Government as if he were a foreign power. She had grown up in the historical castle of Joinville, bought, restored, and magnificently furnished by her father. Montessuy made life give all it could yield. An instinctive and powerful atheist, he wanted all the goods of this world and all the desirable things that earth produces. He accumulated pictures by old masters, and precious sculptures. At fifty he had known all the most beautiful women of the stage, and many in society. He enjoyed everything worldly with the brutality of his temperament and the shrewdness of his mind.

Poor Madame Montessuy, economical and careful, languished at Joinville, delicate and poor, under the frowns of twelve gigantic caryatides which held a ceiling on which Lebrun had painted the Titans struck by Jupiter. There, in the iron cot, placed at the foot of the large bed, she died one night of sadness and exhaustion, never having loved anything on earth except her husband and her little drawing-room in the Rue Maubeuge.

She never had had any intimacy with her daughter, whom she felt instinctively too different from herself, too free, too bold at heart; and she divined in Therese, although she was sweet and good, the strong Montessuy blood, the ardor which had made her suffer so much, and which she forgave in her husband, but not in her daughter.

But Montessuy recognized his daughter and loved her. Like most hearty, full-blooded men, he had hours of charming gayety. Although he lived out of his house a great deal, he breakfasted with her almost every day, and sometimes took her out walking. He understood gowns and furbelows. He instructed and formed Therese. He amused her. Near her, his instinct for conquest inspired him still. He desired to win always, and he won his daughter. He separated her from her mother. Therese admired him, she adored him.

In her dream she saw him as the unique joy of her childhood. She was persuaded that no man in the world was as amiable as her father.

At her entrance in life, she despaired at once of finding elsewhere so rich a nature, such a plenitude of active and thinking forces. This discouragement had followed her in the choice of a husband, and perhaps later in a secret and freer choice.

She had not really selected her husband. She did not know: she had permitted herself to be married by her father, who, then a widower, embarrassed by the care of a girl, had wished to do things quickly and well. He considered the exterior advantages, estimated the eighty years of imperial nobility which Count Martin brought. The idea never came to him that she might wish to find love in marriage.

He flattered himself that she would find in it the satisfaction of the luxurious desires which he attributed to her, the joy of making a display of grandeur, the vulgar pride, the material domination, which were for him all the value of life, as he had no ideas on the subject of the happiness of a true woman, although he was sure that his daughter would remain virtuous.

While thinking of his absurd yet natural faith in her, which accorded so badly with his own experiences and ideas regarding women, she smiled with melancholy irony. And she admired her father the more.

After all, she was not so badly married. Her husband was as good as any other man. He had become quite bearable. Of all that she read in the ashes, in the veiled softness of the lamps, of all her reminiscences, that of their married life was the most vague. She found a few isolated traits of it, some absurd images, a fleeting and fastidious impression. The time had not seemed long and had left nothing behind. Six years had passed, and she did not even remember how she had regained her liberty, so prompt and easy had been her conquest of that husband, cold, sickly, selfish, and polite; of that man dried up and yellowed by business and politics, laborious, ambitious, and commonplace. He liked women only through vanity, and he never had loved his wife. The separation had been frank and complete. And since then, strangers to each other, they felt a tacit, mutual gratitude for their freedom. She would have had some affection for him if she had not found him hypocritical and too subtle in the art of obtaining her signature when he needed money for enterprises that were more for ostentation than real benefit. The man with whom she dined and talked every day had no significance for her.

With her cheek in her hand, before the grate, as if she questioned a sibyl, she saw again the face of the Marquis de Re. She saw it so precisely that it surprised her. The Marquis de Re had been presented to her by her father, who admired him, and he appeared to her grand and dazzling for his thirty years of intimate triumphs and mundane glories. His adventures followed him like a procession. He had captivated three generations of women, and had left in the heart of all those whom he had loved an imperishable memory. His virile grace, his quiet elegance, and his habit of pleasing had prolonged his youth far beyond the ordinary term of years. He noticed particularly the young Countess Martin. The homage of this expert flattered her. She thought of him now with pleasure. He had a marvellous art of conversation. He amused her. She let him see it, and at once he promised to himself, in his heroic frivolity, to finish worthily his happy life by the subjugation of this young woman whom he appreciated above every one else, and who evidently admired him. He displayed, to capture her, the most learned stratagems. But she escaped him very easily.

She yielded, two years later, to Robert Le Menil, who had desired her ardently, with all the warmth of his youth, with all the simplicity of his mind. She said to herself: “I gave myself to him because he loved me.” It was the truth. The truth was, also, that a dumb yet powerful instinct had impelled her, and that she had obeyed the hidden impulse of her being. But even this was not her real self; what awakened her nature at last was the fact that she believed in the sincerity of his sentiment. She had yielded as soon as she had felt that she was loved. She had given herself, quickly, simply. He thought that she had yielded easily. He was mistaken. She had felt the discouragement which the irreparable gives, and that sort of shame which comes of having suddenly something to conceal. Everything that had been whispered before her about other women resounded in her burning ears. But, proud and delicate, she took care to hide the value of the gift she was making. He never suspected her moral uneasiness, which lasted only a few days, and was replaced by perfect tranquillity. After three years she defended her conduct as innocent and natural.

Having done harm to no one, she had no regrets. She was content. She was in love, she was loved. Doubtless she had not felt the intoxication she had expected, but does one ever feel it? She was the friend of the good and honest fellow, much liked by women who passed for disdainful and hard to please, and he had a true affection for her. The pleasure she gave him and the joy of being beautiful for him attached her to this friend. He made life for her not continually delightful, but easy to bear, and at times agreeable.

That which she had not divined in her solitude, notwithstanding vague yearnings and apparently causeless sadness, he had revealed to her. She knew herself when she knew him. It was a happy astonishment. Their sympathies were not in their minds. Her inclination toward him was simple and frank, and at this moment she found pleasure in the idea of meeting him the next day in the little apartment where they had met for three years. With a shake of the head and a shrug of her shoulders, coarser than one would have expected from this exquisite woman, sitting alone by the dying fire, she said to herself: “There! I need love!”

Chapter 2 - “One Can See that You are Young!”

It was no longer daylight when they came out of the little apartment in the Rue Spontini. Robert Le Menil made a sign to a coachman, and entered the carriage with Therese. Close together, they rolled among the vague shadows, cut by sudden lights, through the ghostly city, having in their minds only sweet and vanishing impressions while everything around them seemed confused and fleeting.

The carriage approached the Pont-Neuf. They stepped out. A dry cold made vivid the sombre January weather. Under her veil Therese joyfully inhaled the wind which swept on the hardened soil a dust white as salt. She was glad to wander freely among unknown things. She liked to see the stony landscape which the clearness of the air made distinct; to walk quickly and firmly on the quay where the trees displayed the black tracery of their branches on the horizon reddened by the smoke of the city; to look at the Seine. In the sky the first stars appeared.

“One would think that the wind would put them out,” she said.

He observed, too, that they scintillated a great deal. He did not think it was a sign of rain, as the peasants believe. He had observed, on the contrary, that nine times in ten the scintillation of stars was an augury of fine weather.

Near the little bridge they found old iron-shops lighted by smoky lamps. She ran into them. She turned a corner and went into a shop in which queer stuffs were hanging. Behind the dirty panes a lighted candle showed pots, porcelain vases, a clarinet, and a bride’s wreath.

He did not understand what pleasure she found in her search.

“These shops are full of vermin. What can you find interesting in them?”

“Everything. I think of the poor bride whose wreath is under that globe. The dinner occurred at Maillot. There was a policeman in the procession. There is one in almost all the bridal processions one sees in the park on Saturdays. Don’t they move you, my friend, all these poor, ridiculous, miserable beings who contribute to the grandeur of the past?”

Among cups decorated with flowers she discovered a little knife, the ivory handle of which represented a tall, thin woman with her hair arranged a la Maintenon. She bought it for a few sous. It pleased her, because she already had a fork like it. Le Menil confessed that he had no taste for such things, but said that his aunt knew a great deal about them. At Caen all the merchants knew her. She had restored and furnished her house in proper style. This house was noted as early as 1690. In one of its halls were white cases full of books. His aunt had wished to put them in order. She had found frivolous books in them, ornamented with engravings so unconventional that she had burned them.

“Is she silly, your aunt?” asked Therese.