5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

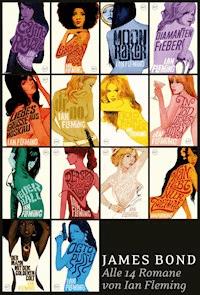

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: James Bond 007

- Sprache: Englisch

Meet James Bond, the world's most famous spy.Set apart from the other books in Ian Fleming's James Bond series, The Spy Who Loved Me is told from the perspective of a femme fatale in the making - a victim of circumstance with a wounded heart.Vivienne Michel, a precocious French Canadian raised in the United Kingdom, seems a foreigner in every land. With only a supercharged Vespa and a handful of American dollars, she travels down winding roads into the pine forests of the Adirondacks. After stopping at the Dreamy Pines Motor Court and being coerced into caretaking at the vacant motel for the night, Viv opens the door to two armed mobsters and realizes being a woman alone is no easy task. But when a third stranger shows - a confident Englishman with a keen sense for sizing things up - the tables are turned.Still reeling in the wake of Operation Thunderball, Bond had planned for his jaunt through the Adirondacks to be a period of rest before his return to Europe. But that all changes when his tire goes flat in front of a certain motel...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 251

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

The Spy Who Loved Me

The Spy WhoLoved Me

IAN FLEMING

Contents

Part OneMe

1: Scaredy Cat

2: Dear Dead Days

3: Spring’s Awakening

4: Dear Viv

5: A Bird with a Wing Down

6: Go West, Young Woman

Part TwoThem

7: Come into My Parlour . . .

8: Dynamite from Nightmare-land

9: Then I Began to Scream

Part ThreeHim

10: Whassat?

11: Bedtime Story

12: To Sleep – Perchance to Die!

13: The Crash of Guns

14: Bimbo

15: The Writing on My Heart

Part One

Me

1

Scaredy Cat

I was running away. I was running away from England, from my childhood, from the winter, from a sequence of untidy, unattractive love affairs, from the few sticks of furniture and jumble of overworn clothes that my London life had collected around me; and I was running away from drabness, fustiness, snobbery, the claustrophobia of close horizons and from my inability, although I am quite an attractive rat, to make headway in the rat-race. In fact, I was running away from almost everything except the Law.

And I had run a very long way indeed – almost, exaggerating a bit, halfway round the world. In fact, I had come all the way from London to The Dreamy Pines Motor Court, which is ten miles west of Lake George, the famous American tourist resort in the Adirondacks – that vast expanse of mountains, lakes and pine forests which forms most of the northern territory of New York State. I had started on September the first, and it was now Friday the thirteenth of October. When I had left, the grimy little row of domesticated maples in my square had been green, or as green as any tree can be in London in August. Now, in the billion-strong army of pine trees that marched away northwards towards the Canadian border, the real, wild maples flamed here and there like shrapnel-bursts. And I felt that I, or at any rate my skin, had changed just as much – from the grimy sallowness that had been the badge of my London life to the snap and colour and sparkle of living out of doors and going to bed early and all those other dear dull things that had been part of my life in Quebec before it was decided that I must go to England and learn to be a ‘lady’. Very unfashionable, of course, this cherry-ripe, strength-through-joy complexion, and I had even stopped using lipstick and nail varnish, but to me it had been like sloughing off a borrowed skin and getting back into my own, and I was childishly happy and pleased with myself whenever I looked in the mirror (that’s another thing – I’ll never say ‘looking-glass’ again; I just don’t have to any more) and found myself not wanting to paint a different face over my own. I’m not being smug about this. I was just running away from the person I’d been for the past five years. I wasn’t particularly pleased with the person I was now, but I had hated and despised the other one, and I was glad to be rid of her face.

Station WOKO (they might have dreamt up a grander call-sign!) in Albany, the capital of New York State and about fifty miles due south of where I was, announced that it was six o’clock. The weather report that followed included a storm warning with gale-force winds. The storm was moving down from the north and would hit Albany around 8 p.m. That meant that I would be having a noisy night. I didn’t mind. Storms don’t frighten me, and although the nearest living soul, as far as I knew, was ten miles away up the not very good secondary road to Lake George, the thought of the pines that would soon be thrashing outside, the thunder and lightning and rain, made me already feel snug and warm and protected in anticipation. And alone! But above all alone! ‘Loneliness becomes a lover, solitude a darling sin.’ Where had I read that? Who had written it? It was so exactly the way I felt, the way that, as a child, I had always felt until I had forced myself to ‘get into the swim’, ‘be one of the crowd’ – a good sort, on the ball, hep. And what a hash I had made of ‘togetherness’! I shrugged the memory of failure away. Everyone doesn’t have to live in a heap. Painters, writers, musicians are lonely people. So are statesmen and admirals and generals. But then, I added to be fair, so are criminals and lunatics. Let’s just say, not to be too flattering, that true individuals are lonely. It’s not a virtue, the reverse if anything. One ought to share and communicate if one is to be a useful member of the tribe. The fact that I was so much happier when I was alone was surely the sign of a faulty, a neurotic character. I had said this so often to myself in the past five years that now, that evening, I just shrugged my shoulders and, hugging my solitude to me, walked across the big lobby to the door and went out to have a last look at the evening.

I hate pine trees. They are dark and stand very still and you can’t shelter under them or climb them. They are very dirty, with a most untreelike black dirt, and if you get this dirt mixed with their resin they make you really filthy. I find their jagged shapes vaguely inimical, and the way they mass so closely together gives me the impression of an army of spears barring my passage. The only good thing about them is their smell, and, when I can get hold of it, I use pine-needle essence in my bath. Here, in the Adirondacks, the endless vista of pine trees was positively sickening. They clothe every square yard of earth in the valleys and climb up to the top of every mountain so that the impression is of a spiky carpet spread to the horizon – an endless vista of rather stupid-looking green pyramids waiting to be cut down for matches and coat hangers and copies of the New York Times.

Five acres or so of these stupid trees had been cleared to build the motel, which is all that this place really was. ‘Motel’ isn’t a good word any longer. It has become smart to use ‘Motor Court’ or ‘Ranch Cabins’ ever since motels became associated with prostitution, gangsters and murders, for all of which their anonymity and lack of supervision is a convenience. The site, tourist-wise, in the lingo of the trade, was a good one. There was this wandering secondary road through the forest, which was a pleasant alternative route between Lake George and Glens Falls to the south, and halfway along it was a small lake, cutely called Dreamy Waters, that is a traditional favourite with picnickers. It was on the southern shore of this lake that the motel had been built, its reception lobby facing the road with, behind this main building, the rooms fanning out in a semicircle. There were forty rooms with kitchen, shower and lavatory, and they all had some kind of a view of the lake behind them. The whole construction and design was the latest thing – glazed pitch-pine frontages and pretty timber roofs all over knobbles, air-conditioning, television in every cabin, children’s playground, swimming pool, golf range out over the lake with floating balls (fifty balls, one dollar) – all the gimmicks. Food? Cafeteria in the lobby, and grocery and liquor deliveries twice a day from Lake George. All this for ten dollars single and sixteen double. No wonder that, with around two hundred thousand dollars’ capital outlay and a season lasting only from July the first to the beginning of October, or, so far as the NO VACANCY sign was concerned, from July fourteenth to Labour Day, the owners were finding the going hard. Or so those dreadful Phanceys had told me when they’d taken me on as receptionist for only thirty dollars a week plus keep. Thank heavens they were out of my hair! Song in my heart? There had been the whole heavenly choir at six o’clock that morning when their shiny station-wagon had disappeared down the road on their way to Glens Falls and then to Troy where the monsters came from. Mr Phancey had made a last grab at me and I hadn’t been quick enough. His free hand had run like a fast lizard over my body before I had crunched my heel into his instep. He had let go then. When his contorted face had cleared, he said softly, ‘All right, sex-box. Just see that you mind camp good until the boss comes to take over the keys tomorrow midday. Happy dreams tonight.’ Then he had grinned a grin I hadn’t understood, and had gone over to the station-wagon where his wife had been watching from the driver’s seat. ‘Come on, Jed,’ she had said sharply. ‘You can work off those urges on West Street tonight.’ She put the car in gear and called over to me sweetly, ‘ ’Bye now, cutie-pie. Write us every day.’ Then she had wiped the crooked smile off her face and I caught a last glimpse of her withered, hatchet profile as the car turned out on to the road. Phew! What a couple! Right out of a book – and what a book! Dear Diary! Well, people couldn’t come much worse, and now they’d gone. From now on, on my travels, the human race must improve!

I had been standing there, looking down the way the Phanceys had gone, remembering them. Now I turned and looked to the north to see after the weather. It had been a beautiful day, Swiss clear and hot for the middle of October, but now high fretful clouds, black with jagged pink hair from the setting sun, were piling down the sky. Fast little winds were zigzagging among the forest tops and every now and then they hit the single yellow light above the deserted gas station down the road at the tail of the lake and set it swaying. When a longer gust reached me, cold and buffeting, it brought with it the whisper of a metallic squeak from the dancing light, and the first time this happened I shivered deliciously at the little ghostly noise. On the lake shore, beyond the last of the cabins, small waves were lapping fast against the stones and the gunmetal surface of the lake was fretted with sudden cat’s paws that sometimes showed a fleck of white. But, in between the angry gusts, the air was still, and the sentinel trees across the road and behind the motel seemed to be pressing silently closer to huddle round the campfire of the brightly lit building at my back.

I suddenly wanted to go to the loo, and I smiled to myself. It was the piercing tickle that comes to children during hide-and-seek-in-the-dark and ‘sardines’, when, in your cupboard under the stairs, you heard the soft creak of a floorboard, the approaching whisper of the searchers. Then you clutched yourself in thrilling anguish and squeezed your legs together and waited for the ecstasy of discovery, the crack of light from the opening door and then – the supreme moment – your urgent ‘Ssh! Come in with me!’, the softly closing door and the giggling warm body pressed tight against your own.

Standing there, a ‘big girl’ now, I remembered it all and recognised the sensual itch brought on by a fleeting apprehension – the shiver down the spine, the intuitive gooseflesh that come from the primitive fear-signals of animal ancestors. I was amused and I hugged the moment to me. Soon the thunderheads would burst and I would step back from the howl and chaos of the storm into my well-lighted, comfortable cave, make myself a drink, listen to the radio and feel safe and cosseted.

It was getting dark. Tonight there would be no evening chorus from the birds. They had long ago read the signs and disappeared into their own shelters in the forest, as had the animals – the squirrels and the chipmunks and the deer. In all this huge, wild area there was now only me out in the open. I took a last few deep breaths of the soft, moist air. The humidity had strengthened the scent of pine and moss, and now there was also a strong underlying armpit smell of earth. It was almost as if the forest was sweating with the same pleasurable excitement I was feeling. Somewhere, from quite close, a nervous owl asked loudly ‘Who?’ and then was silent. I took a few steps away from the lighted doorway and stood in the middle of the dusty road, looking north. A strong gust of wind hit me and blew back my hair. Lightning threw a quick blue-white hand across the horizon. Seconds later, thunder growled softly like a wakening guard dog, and then the big wind came and the tops of the trees began to dance and thrash and the yellow light over the gas station jigged and blinked down the road as if to warn me. It was warning me. Suddenly the dancing light was blurred with rain, its luminosity fogged by an advancing grey sheet of water. The first heavy drops hit me, and I turned and ran.

I banged the door behind me, locked it and put up the chain. I was only just in time. Then the avalanche crashed down and settled into a steady roar of water whose patterns of sound varied from a heavy drumming on the slanting timbers of the roof to a higher, more precise slashing at the windows. In a moment these sounds were joined by the busy violence of the overflow drainpipes. And the noisy background pattern of the storm was set.

I was still standing there, cosily listening, when the thunder, that had been creeping quietly up behind my back, sprang its ambush. Suddenly lightning blazed in the room, and at the same instant there came a blockbusting crash that shook the building and made the air twang like piano wire. It was just one, single, colossal explosion that might have been a huge bomb falling only yards away. There was a sharp tinkle as a piece of glass fell out of one of the windows on to the floor, and then the noise of water pattering in on to the linoleum.

I didn’t move. I couldn’t. I stood and cringed, my hands over my ears. I hadn’t meant it to be like this! The silence, that had been deafening, resolved itself back into the roar of the rain, the roar that had been so comforting but that now said, ‘You hadn’t thought it could be so bad. You had never seen a storm in these mountains. Pretty flimsy this little shelter of yours, really. How’d you like to have the lights put out as a start? Then the crash of a thunderbolt through that matchwood ceiling of yours? Then, just to finish you off, lightning to set fire to the place – perhaps electrocute you? Or shall we just frighten you so much that you dash out in the rain and try and make those ten miles to Lake George. Like to be alone do you? Well, just try this for size!’ Again the room turned blue-white, again, just overhead, there came the ear-splitting crack of the explosion, but this time the crack widened and racketed to and fro in a furious cannonade that set the cups and glasses rattling behind the bar and made the woodwork creak with the pressure of the sound waves.

My legs felt weak and I faltered to the nearest chair and sat down, my head in my hands. How could I have been so foolish, so, so impudent? If only someone would come, someone to stay with me, someone to tell me that this was only a storm! But it wasn’t! It was catastrophe, the end of the world! And all aimed at me! Now! It would be coming again! Any minute now! I must do something, get help! But the Phanceys had paid off the telephone company and the service had been disconnected. There was only one hope! I got up and ran to the door, reaching up for the big switch that controlled the ‘Vacancy/No Vacancy’ sign in red neon above the threshold. If I put it to ‘Vacancy’, there might be someone driving down the road. Someone who would be glad of shelter. But, as I pulled the switch, the lightning, that had been watching me, crackled viciously in the room, and, as the thunder crashed, I was seized by a giant hand and hurled to the floor.

2

Dear Dead Days

When I came to, I at once knew where I was and what had happened and I cringed closer to the floor, waiting to be hit again. I stayed like that for about ten minutes, listening to the roar of the rain, wondering if the electric shock had done me permanent damage, burnt me, inside perhaps, making me unable to have babies, or turned my hair white. Perhaps all my hair had been burnt off! I moved a hand to it. It felt all right, though there was a bump at the back of my head. Gingerly I moved. Nothing was broken. There was no harm. And then the big General Electric icebox in the corner burst into life and began its cheerful, domestic throbbing and I realised that the world was still going on and that the thunder had gone away and I got rather weakly to my feet and looked about me, expecting I don’t know what scene of chaos and destruction. But there it all was, just as I had ‘left’ it – the important-looking reception desk, the wire rack of paperbacks and magazines, the long counter of the cafeteria, the dozen neat tables with rainbow-hued plastic tops and uncomfortable little metal chairs, the big ice-water container and the gleaming coffee percolator – everything in its place, just as ordinary as could be. There was only the hole in the window and a spreading pool of water on the floor as evidence of the holocaust through which this room and I had just passed. Holocaust? What was I talking about? The only holocaust had been in my head! There was a storm. There had been thunder and lightning. I had been terrified, like a child, by the big bangs. Like an idiot I had taken hold of the electric switch – not even waiting for the pause between lightning flashes, but choosing just the moment when another flash was due. It had knocked me out. I had been punished with a bump on the head. Served me right, stupid, ignorant scaredy cat! But wait a minute! Perhaps my hair had turned white! I walked, rather fast, across the room, picked up my bag from the desk and went behind the bar of the cafeteria and bent down and looked into the long piece of mirror below the shelves. I looked first inquiringly into my eyes. They gazed back at me, blue, clear, but wide with surmise. The lashes were there and the eyebrows, brown, an expanse of inquiring forehead and then, yes, the sharp, brown peak and the tumble of perfectly ordinary, very dark brown hair curving away to right and left in two big waves. So! I took out my comb and ran it brusquely, angrily through my hair, put the comb back in my bag and snapped the clasp.

My watch said it was nearly seven o’clock. I switched on the radio, and while I listened to WOKO frightening its audience about the storm – power lines down, the Hudson River rising dangerously at Glens Falls, a fallen elm blocking Route 9 at Saratoga Springs, flood warning at Mechanicville – I strapped a bit of cardboard over the broken window-pane with Scotch tape and got a cloth and bucket and mopped up the pool of water on the floor. Then I ran across the short covered way to the cabins out back and went into mine, Number 9 on the right-hand side towards the lake, and took off my clothes and had a cold shower. My white Terylene shirt was smudged from my fall and I washed it and hung it up to dry.

I had already forgotten my chastisement by the storm and the fact that I had behaved like a silly goose, and my heart was singing again with the prospect of my solitary evening and of being on my way the next day. On an impulse, I put on the best I had in my tiny wardrobe – my black velvet toreador pants with the rather indecent gold zip down the seat, itself most unchastely tight, and, not bothering with a bra, my golden thread Camelot sweater with the wide floppy turtleneck. I admired myself in the mirror, decided to pull my sleeves up above the elbows, slipped my feet into my gold Ferragamo sandals, and did the quick dash back to the lobby. There was just one good drink left in the quart of Virginia Gentleman bourbon that had already lasted me two weeks, and I filled one of the best cut-glass tumblers with ice cubes and poured the bourbon over them, shaking the bottle to get out the last drop. Then I pulled the most comfortable armchair over from the reception side of the room to stand beside the radio, turned the radio up, lit a Parliament from the last five in my box, took a stiff pull at my drink, and curled myself into the armchair.

The commercial, all about cats and how they loved Pussyfoot Prime Liver Meal, lilted on against the steady roar of the rain, whose tone only altered when a particularly heavy gust of wind hurled the water like grapeshot at the windows and softly shook the building. Inside, it was just as I had visualised – weatherproof, cosy and gay and glittering with lights and chromium. WOKO announced forty minutes of ‘Music To Kiss By’ and suddenly there were the Ink Spots singing ‘Someone’s Rockin’ My Dream Boat’ and I was back on the River Thames and it was five summers ago and we were drifting down past King’s Eyot in a punt and there was Windsor Castle in the distance and Derek was paddling while I worked the portable. We only had ten records, but whenever it came to be the turn of the Ink Spots’ LP and the record got to ‘Dream Boat’, Derek would always plead, ‘Play it again, Viv,’ and I would have to go down on my knees and find the place with the needle.

So now my eyes filled with tears – not because of Derek, but because of the sweet pain of boy and girl and sunshine and first love with its tunes and snapshots and letters ‘Sealed With A Loving Kiss’. They were tears of sentiment for lost childhood, and of self-pity for the pain that had been its winding sheet, and I let two tears roll down my cheeks before I brushed them away and decided to have a short orgy of remembering.

My name is Vivienne Michel and, at the time I was sitting in The Dreamy Pines motel and remembering, I was twenty-three. I am five feet six, and I always thought I had a good figure until the English girls at Astor House told me my behind stuck out too much and that I must wear a tighter bra. My eyes, as I have said, are blue and my hair a dark brown with a natural wave and my ambition is one day to give it a lion’s streak to make me look older and more dashing. I like my rather high cheekbones, although these same girls said they made me look ‘foreign’, but my nose is too small, and my mouth too big so that it often looks sexy when I don’t want it to. I have a sanguine temperament which I like to think is romantically tinged with melancholy, but I am wayward and independent to an extent that worried the sisters at the Convent and exasperated Miss Threadgold at Astor House. (‘Women should be willows, Vivienne. It is for men to be oak and ash.’)

I am French-Canadian. I was born just outside Quebec at a little place called Sainte Famille on the north coast of the Île d’Orléans, a long island that lies like a huge sunken ship in the middle of the St Lawrence River where it approaches the Quebec Straits. I grew up in and beside this great river, with the result that my main hobbies are swimming and fishing and camping and other outdoor things. I can’t remember much about my parents – except that I loved my father and got on badly with my mother – because when I was eight they were both killed in a wartime air crash coming in to land at Montreal on their way to a wedding. The courts made me a ward of my widowed aunt, Florence Toussaint, and she moved into our little house and brought me up. We got on all right, and today I almost love her, but she was a Protestant, while I had been brought up as a Catholic, and I became the victim of the religious tug of war that has always been the bane of priest-ridden Quebec, so nearly exactly divided between the faiths. The Catholics won the battle over my spiritual well-being, and I was educated in the Ursuline Convent until I was fifteen. The sisters were strict and the accent was very much on piety, with the result that I learnt a great deal of religious history and rather obscure dogma which I would gladly have exchanged for subjects that would have fitted me to be something other than a nurse or a nun and, when in the end the atmosphere became so stifling to my spirit that I begged to be taken away, my aunt gladly rescued me from ‘The Papists’ and it was decided that, at the age of sixteen, I should go to England and be ‘finished’. This caused something of a local hullabaloo. Not only are the Ursulines the centre of Catholic tradition in Quebec – the Convent proudly owns the skull of Montcalm: for two centuries there have never been less than nine sisters kneeling at prayer, night and day, before the chapel altar – but my family had belonged to the very innermost citadel of French-Canadianism and that their daughter should flout both treasured folkways at one blow was a nine days’ wonder – and scandal.

The true sons and daughters of Quebec form a society, almost a secret society, that must be as powerful as the Calvinist clique of Geneva, and the initiates refer to themselves proudly, male or female, as Canadiennes. Lower, much lower, down the scale come the Canadiens – Protestant Canadians. Then Les Anglais, which embraces all more or less recent immigrants from Britain, and lastly, Les Américains, a term of contempt. The Canadiennes pride themselves on their spoken French, although it is a bastard patois full of two-hundred-year-old words which Frenchmen themselves don’t understand and is larded with Frenchified English words – rather, I suppose, like the relationship of Afrikaans to the language of the Dutch. The snobbery and exclusiveness of this Quebec clique extend even towards the French who live in France. These mother-people to the Canadiennes are referred to simply as Étrangers! I have told all this at some length to explain that the defection from The Faith of a Michel from Sainte Famille was almost as heinous a crime as a defection, if that were possible, from the Mafia in Sicily, and it was made pretty plain to me that, in leaving the Ursulines and Quebec, I had just about burnt my bridges so far as my spiritual guardians and my home town were concerned.

My aunt sensibly pooh-poohed my nerves over the social ostracism that followed – most of my friends were forbidden to have anything to do with me – but the fact remains that I arrived in England loaded with a sense of guilt and ‘difference’ that, added to my ‘colonialism’, were dreadful psychological burdens with which to face a smart finishing school for young ladies.

Miss Threadgold’s Astor House was, like most of these very English establishments, in the Sunningdale area – a large Victorian stockbrokery kind of place, whose upper floors had been divided up with plasterboard to make bedrooms for twenty-five pairs of girls. Being a ‘foreigner’ I was teamed up with the other foreigner, a dusky Lebanese millionairess with huge tufts of mouse-coloured hair in her armpits, and an equal passion for chocolate fudge and an Egyptian film star called Ben Saïd, whose gleaming photograph – gleaming teeth, moustache, eyes and hair – was soon to be torn up and flushed down the lavatory by the three senior girls of Rose Dormitory, of which we were both members. Actually I was saved by the Lebanese. She was so dreadful, petulant, smelly and obsessed with her money that most of the school took pity on me and went out of their way to be kind. But there were many others who didn’t, and I was made to suffer agonies for my accent, my table manners, which were considered uncouth, my total lack of savoir faire and, in general, for being a Canadian. I was also, I see now, much too sensitive and quick-tempered. I just wouldn’t take the bullying and teasing, and when I had roughed up two or three of my tormentors, others got together with them and set upon me in bed one night and punched and pinched and soaked me with water until I burst into tears and promised I wouldn’t ‘fight like an elk’ any more. After that, I gradually settled down, made an armistice with the place, and morosely set about learning to be a ‘lady’.