Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

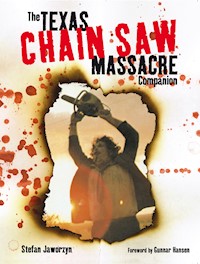

In 1974, a low-budget, no-star horror movie was unleashed on the world, causing panic among the censors and provoking glee from its intended audience. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is still as powerful today as when it was first seen almost thirty years ago, and will return to the screens in a high profile remake this Halloween. Now, in this long-awaited companion to Tobe Hooper's groundbreaking film, Stefan Jaworzyn gives us the inside story of one of the most successful, controversial and influential horror films ever made, as well as in-depth coverage of the three sequels, various documentaries and other movies also based on the life of serial killer Ed Gein. Packed with exclusive interviews, rare and unseen pictures, and with a foreword from the chainsaw-wielding Leatherface himself, Gunnar Hansen!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 471

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE COMPANION

9781781164976

Published by

Titan Books

A division of

Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition October 2003

10987654321

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Companion copyright © 2003 Stefan Jaworzyn. All rights reserved.

Foreword copyright © 2003 Gunnar Hansen. All rights reserved.

Front cover image courtesy of Vortex Inc./Kim Henkel/Tobe Hooper, © 1974 Vortex, Inc.

Picture credits

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following for the use of their visual material, used solely for the advertising, promotion, publicity and review of the specific motion pictures they illustrate. All rights reserved. Braveworld Ltd, Cannon International, Mary Church, Columbia TriStar, Exploited Films, Guild Film Distribution, Hollywood DVD, Eric Lasher, Mars Productions, Media, Metro Tartan Pictures, MGM Home Entertainment, MTI Video, New Line Cinema & Video, Pathé Films, Trisomy Films, Ultra Muchos Inc/River City Films Inc, Universal, Vestron, Vortex Inc./Kim Henkel/Tobe Hooper. Any omissions will be corrected in future editions.

The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees in this book are not necessarily those of the author or publisher, and the author and publisher accept no responsibility for inaccuracies or omissions, and the author and publisher specifically disclaim any liability, loss, or risk, whether personal, financial, or otherwise, that is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, from the contents of this book.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at: [email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address. Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com. To subscribe to our regular newsletter for up-to-the-minute news, great offers and competitions, email: [email protected]. Titan books are available from all good bookshops or direct from our mail order service. For a free catalogue or to order, phone 01536 76 46 46 with your credit card details or contact Titan Books Mail Order, Unit 6, Pipewell Industrial Estate, Desborough, Kettering, Northants NN14 2SW, quoting reference TC/MC.

The right of Stefan Jaworzyn to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG, Bodmin, Cornwall.

TheTEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRECompanion

STEFAN JAWORZYN

FOREWORD BY GUNNAR HANSEN

TITAN BOOKS

Acknowledgements

Firstly, to all the cast and crew members from the films who contributed to this book. Many went out of their way to help with resources, contacts and follow-up interviews. Without them this project really would have been impossible and this book is dedicated to them:

Wayne Bell, Joe Bob Briggs, Marilyn Burns, Robert A. Burns, Allen Danziger, Duane Graves, Ed Guinn, Gunnar Hansen, Kim Henkel, Brian Huberman, Levie Isaacks, Bill Johnson, Richard Kidd, Richard Kooris, Robert Kuhn, Eric Lasher, Jim Moran, Bill Moseley, Paul Partain, Lou Perryman, Sallye Richardson, David J. Schow, Brad Shellady, Jim Siedow, Mike Sullivan/Michael O’Sullivan.

Steve Pittis, without whose encouragement and resources I probably wouldn’t have started on this project.

People who provided help, research materials and/or encouragement:

Chuck Grigson, Jay Grossman/MTI Video, David Hyman, Alan Jones (additional credit: sneering and contempt — I couldn’t live without it), Stephen Jones, Craig Lapper, Edwin Pouncey, John Scoleri.

Others who provided research material or help in other ways:

Ryan Adams, The Austin Chronicle/Marc Savlov, Steve Beeho, Blue Dolphin Films, British Board of Film Classification, Cinefantastique magazine, CineSchlock-o-rama/G. Noel Gross, Fangoria magazine, Film Comment, Royce Freeman, Tim Harden, Harper’s Magazine, International Cinematographer’s Guild/Bob Fisher, David Kerekes, Living-Dead.com/Ryan Rotten, New Line Cinema, Kim Newman, Phil Nutman, The Onion a.v. club, Spencer Perskin, Variety, Video Watchdog/Tim Lucas.

And thanks of course to the staff at Titan Books (David Barraclough, Adam Newell, Katy Wild) for reminding me of the true nature of horror.

(In absentia: Tobe Hooper.)

CONTENTS

Foreword by Gunnar Hansen

Unexpected

Prelude: Eggshells

“Psychedelic Crap!”

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

“We Just Want to Make Something For a Buck”

Fixing It: The Joys of Post-Production

30 Years After and It Just Won’t Die!

Texas Chain Saw and the British Censor

“The Pornography of Terror”

Texas Chain Saw and the Critics

“The Absolute Degradation of the Artistic Imagination”

The Career of Tobe Hooper

Eaten Alive

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2

“This Is the Cinema of Excess!”

“Worth Cutting Further”

Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III

“Junior Likes Them Private Parts”

The Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre

“There’s No Way You Can Go Over the Top!”

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2003

“A Unique Way of Grossing People Out”

Documentaries and Associated Films

“The Texture of Human Beings at Work”

The Life and Crimes of Ed Gein

“A Human Horror Story of Ghastly Proportions”

Afterword

A Horror Film to Scare the Shit Out of You

Cast of Characters

Credits, Select Bibliography and Weblinks

Publisher’s Note

All quotes in the text are taken from interviews conducted by the author, unless otherwise attributed. For detailed ‘who’s who’ information, please refer to the ‘Cast of Characters’ section.

Foreword by Gunnar Hansen

UNEXPECTED

One recent spring day, Marilyn Burns and I took a walk on Regent Street, in London. We found a small pub and went inside for lunch. As we sat at the table contemplating our bangers and mash, Marilyn started to laugh. ‘I never thought,’ she said, ‘that thirty years later you and I would be having a beer in a pub in London. All because of the movie.’ The movie was The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and Marilyn had played Sally, the one victim in that misadventure to escape alive. I had played Leatherface, the brutish killer who, at the end, had danced and swung his chainsaw in frustration at her escape. We were in London for a few days to promote the UK release of a new DVD celebrating the movie’s thirtieth anniversary.

Marilyn was right: given what we had known back then, neither of us would ever have imagined such a thing. In fact, most of what has happened in these thirty years since the movie was released has been entirely unforeseen. When we were making Chain Saw, we were not expecting very much. Of course we wanted it to be a good movie. Of course we hoped people would like it.

But at best, I thought, it was just a low-budget horror movie. If we were lucky, it would earn enough money to make the investors happy, and a few hardcore horror movie fans would remember it for a while. After that it would fade into obscurity. We had even joked on the set that this, at least, was one movie that would never be on television.

I thought the highlight of the movie for me would be our ersatz première at a small theatre in Austin, Texas, just before Halloween 1974. The manager let me in for free after I convinced him I had been in the movie. Afterwards a few friends gathered in the parking lot, where they gave me a defunct chainsaw, and we signed the charter for the Gunnar Hansen Fan Club in red ink. We had a lot of fun that night. And that, I figured, was that.

Gunnar Hansen in the role of Leatherface, an icon of modern horror cinema.

The real Gunnar Hansen.

Well, wrong.

Almost immediately the reviews started coming in, and we knew that we had something hot. One Philadelphia newspaper published articles about how angered and revolted theatre-goers had been at the movie’s explicit violence. They were, the writer claimed, leaving the theatre physically ill and demanding their money back. Of course, none of what they were complaining about is in the movie. For all its supposed violence, it is very tame compared to mainstream action movies such as Raiders of the Lost Ark. Almost all its violence is implied, even if some reviewers call it the original splatter movie.

These complaints were echoed by a talk show host who griped to his audience one night on national TV that movies like Chain Saw should get an X rating, not the tame R that it had received. My favourite angry review came in Harper’s Magazine, which called Chain Saw a ‘vile little piece of sick crap with literally nothing to recommend it.’ Of course this condemnation only increased interest in the movie.

Then New York film reviewer Rex Reed stepped into the middle of this. He praised Chain Saw. Said it was the scariest movie he’d ever seen. Or something like that.

Suddenly the movie was very big. People were jamming the theatres to see it. People talked about it. Everybody, not just hardcore horror fans, had heard of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. (And in spite of our earlier joking, I even saw it on TV one night in my hotel room in Paris. In French.) And, as we listened to all the hubbub, we realized that this movie was going to be more than we expected. This movie was going to be known. And it was going to make us a lot of money.

Well, wrong again. Eventually a few small royalty checks dribbled in, but we never got a big pay-off. No one knows how much money it made. Some estimate that it grossed $50 million. Others say $100 million. But we’ll never know. Lawsuits popped up over a period of years — some involved with the film sued others to get at the money. It did no good, though — no one ever got much out of it. After all this time, the one thing I do know about the finances is that I didn’t see any of those imagined millions.

Not that it mattered much. It would have been nice to get the money, but that wasn’t why I worked on the movie. As I said, I just wanted to do something interesting during the summer. And I got that. I got to make a movie. I got to work with people who were very good at what they did and who gave their best effort. That is something I’ve carried with me — since then I, too, have tried to be good at what I do, and to do my best. I also learned how a movie is made, something few people get to see.

In these thirty years since Chain Saw ’s release I continue to be amazed by how it has turned out to be so much more than what we expected. Movie-makers want to copy the movie. Fans still want to see it. And everybody — not just fans — has an opinion about it.

Some people are still angry after all these years. How dare I, they demand, make such a thing? It represents everything that’s wrong with the movies. I was the reason, one woman claimed, that a dozen people had recently been murdered in New York City.

But mostly the talk is positive.

I go to horror conventions a few times a year to meet fans (who would have expected that?). And here, not only do people remember and love Chain Saw, but each generation rediscovers it. I meet young boys and girls — thirteen or fourteen years old — who have just seen it for the first time, and are fascinated. I meet people in their fifties and sixties who saw it back in ’74, and still have something to say about it. I meet people who are convinced it’s true: ‘I remember when it happened,’ one says. ‘It was in all the papers. It was very scary.’ ‘I knew the original Leatherface,’ another claims. ‘I was a guard at the Texas State Prison, and Leatherface was a prisoner there. He worked in the kitchen.’

All because of this little horror movie we made one summer thirty years ago.

And so, despite our expectations, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is still around. And it’s thriving. It has entered the culture — it’s hard to pick up a chainsaw now without having it mean something menacing. People still tell me chainsaw jokes. (They’re not funny.) Even people who don’t know horror movies know who Leatherface is. A copy of Chain Saw sits in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, in New York. Recently I bought a Texas Chain Saw Massacre lunch box. There are even Leatherface action figures, some eight or nine different ones, including a Bobblehead Leatherface. Who knew?

The movie has proved to be so much more than we could imagine at the time. And the proof was in Marilyn’s laugh in that London pub so many years later.

Gunnar Hansen

Northeast Harbor

April 2003

Prelude: Eggshells

“PSYCHEDELIC CRAP!”

Sallye Richardson: First of all, you think this thing revolves around Tobe Hooper and then you think, well no, maybe not — in part he is the central focus — but whose story is this? Is it a story about Tobe and his movies or is it a story about a lot of people at a particular time?

Gunnar Hansen: What you’ll probably find about this is, we each have our own take on Chain Saw — this is like Rashomon, where we each tell the story... So between five of us we’d have five different stories...

Sallye Richardson: The thing about it is, I’ve heard a lot of different stories — it’s interesting for me because I happen to know the truth — whatever anybody says, that’s fine, but I happen to know the truth... And it’s interesting that people have their own perspective on what happened — everybody sees things differently — some people stretch the truth, and would like it to look like something that it’s not. So it’s an interesting phenomenon — just like what you write will be a compilation of what you have experienced, filtering it through yourself...

_____________

After spending the greater part of the 1960s producing a large body of short films, documentaries and commercials, Tobe Hooper’s first feature film was Eggshells, shot between 1969-1970. Its late hippie-period sensibilities — psychedelic visuals, fragmented, semi-improvised narrative — coupled with incomprehensible artiness left it something short of a commercial venture, destined to play at festivals (it won a gold award at the Atlanta International Film Festival) and a handful of university campuses before being sold as a tax write-off and never seen again.

Left: Eggshellsposter artwork by Jim Franklin.

Lou Perryman: My brother Ron and Tobe were buddies, they were partners, they were the two hot film-makers in town — they had aspirations, they talked about directors and scriptwriters, knew all the stuff. When I moved to Austin, I remember seeing Tobe editing a film for my brother on this ‘hot splicer’ — where you actually clip and scrape and then glue the pieces of film together, whereas a guillotine splicer is one where you tape it and it’s your work print — and I knew he had this visual sense about him. So they would put these films together and talk about them — mostly I would go for cigars and Cokes...

Richard Kidd: I had gone to work for KTVC, a local television station owned by Lyndon Johnson here in Austin, while I was finishing my last years at The University of Texas (UT). I met a fellow camera person also working in the news department, Gary Pickle. So Gary and I decided to leave the television station and start a film company, it was that simple — we didn’t have too many ideas about it, we just thought we could do it on our own. That must have been about 1966. There was another fellow recruited from the TV station, Mike Bosler, who has since died. I guess we did that for about a year, and that’s when we hooked up with Tobe and Ron, both of whom would come into the category of being real creative types. They were trying to make films, do commercials, get started in the business, but they didn’t really have an office, they were just kind of doing it out of their homes. We had rented a small office building near the state capitol, we were an honest-to-goodness legitimate business!

Sallye Richardson: I graduated from UT film school with a degree in film — the department was still very new. After I graduated I went out and did a documentary for a children’s mental health facility, then I met Lou Perryman and we did a second film for the same people. I took the film into Richard Kidd’s company Motion Picture Productions (MPP), where I could use their equipment in exchange for bringing the film in. So I used their post-production facilities, and that’s how I got started with the company. I met Tobe there. I learned so many things about photography from both Tobe and Ron Perryman — Ron was so good at lighting, he had a speciality of doing the long slow shot — he would set up and wait for the sunset, or he would set up with a long lens with someone running in the distance and there’d be a real slow pan that would be so delicate, and it would be lit incredibly. Ron and Tobe complemented each other so well because Tobe was quick and upside down and sideways and Ron had the meticulously slow, beautiful shots — he did so much beautiful work. Ron shot commercials too, and they always had a beautiful quality — softer, slow, beautifully lit, meticulously crafted. They liked working together because they added something to each other, a lot of things they did together were really neat... I was always sad that Ron was not able to put it together to go forward with his career...

Tobe Hooper at work.

Lou Perryman: Tobe had made another movie, a short film, way back, The Heisters — I think it was shot in 35mm. I remember being on that set, must have been about ’62...

Sallye Richardson: I believe it was his first film, I think he just made that by himself — he’s probably the only person with a copy of it — it was a comedy, a slapstick thing. He brought out this giant pie, and this guy gets hit in the face with a pie that’s about as big as a door...

David Ford (left) and Tobe Hooper (right) receive the gold award at the Atlanta International Film Festival.

Lou Perryman: Tobe and Ron were invited to join MPP by Richard Kidd. In some ways he’s the one who had the dream of a film company — Ron and Tobe were the artists and they wanted to do ‘art’, and Richard’s grabbing a camera and running down to a bank and clicking off a bunch of shots and making a commercial out of it. They were just horrified — that’s not art! But he kept it alive, he paid the bills...

Sallye Richardson: Richard Kidd was a phenomenal film-maker, though he’s a commercial film-maker, not an artist. He was able to keep that group of artists together in some manner and still support a company, and it was through his wiles that it managed to stay afloat. I don’t know how he did it sometimes! He knows how to get something out — and forget the art! MPP became Film House because Ron and Tobe along with this other guy, Gary Pickle, tried to make it ‘less Richard’ — they felt like they needed a new name, but it was still basically ‘Richard Kidd Productions’. Everybody left him but he survived — moved to Dallas and became even more successful!

Richard Kidd: MPP changed its name to Film House, maybe ’69 or ’70. When Gary and I started up, we couldn’t think of what to call it so it ended up Motion Picture Productions. Talk about a stupid name! So when we got Ron and Tobe, they said, ‘We need to come up with a better name than MPP,’ so that’s where Film House came from, and that was the operational name till the mid-’70s when everybody split and RKP was born.

The mysterious ‘Boris Schnurr’ (aka Kim Henkel) and Mahlon Forman relax.

Sallye Richardson: If there was a commercial to shoot for the bank in Austin, Richard would say, ‘Tobe, you got to go do this one.’ He would give him the sheet the agency had provided — Tobe would look at it, and we’d go down and there’d be, say, ten people we were supposed to interview. But Tobe would be walking around doing hand-held stuff — that was who he was. If he needed a set-up shot he’d maybe take Ron. He’d bring it back, drop it off with us, then go away until it was ready. Then he’d sit down at the Steenbeck and he would perform this miracle. He’d have film hanging round his neck, taped to his coat — and in almost no time he’d have this imaginative thing that was just great. Perhaps not exactly as the Austin National Bank or the agency would necessarily have liked, but it was so magical that, gosh, who couldn’t like it! He was a great cameraman and has always been an excellent editor.

Richard Kooris: I knew the guys at MPP — I freelanced for them on occasion, but in the early ’70s I started a production company called Shootout with some students, one of whom was Danny Pearl, and we became competitors with MPP. We had a little office above a chiropractor’s. Initially we didn’t own any equipment, then we got a six-plate Steenbeck — a 16mm editing table — and we’d rent cameras, do whatever work we could get. The other guys were Larry Carroll, Ted Nicolaou and Courtney Goodin...

I had known Richard Kidd for years, and of course Tobe — he started making films when he was really young, and down at MPP was where he got his education — and a guy named Ron Perryman, who was a sort of mad genius. He’s Lou’s older brother — I haven’t seen him for years, he’s sort of a recluse, I don’t think his health is too good either. He was a wonderful photographer, just a brilliant photographer, but he was a very strange individual... He had a great eye, and was technically really inventive — he built cameras and cranes and all sorts of devices.

Richard Kidd: Ron was pretty much a recluse even by the early ’70s. He was a true talent but he wanted to do it his own way, and he didn’t want anybody messing with him — you could never send Ron on a corporate job without handlers and managers and producers around, someone to run interference!

Robert A. Burns: I grew up in Austin, as did Tobe — Tobe and I met in 1965 at a small impromptu party after some small stage production in Austin. We decided to have it at my tiny house trailer but it got broken up before it started when the weird park owner thought I was opening up a whorehouse (I wish!). He then threw me out of the park.

I worked with Tobe on a couple of his projects. He did a fine little short picture called Down Friday Street, not a documentary per se, just a short thing about ‘too bad they’re tearing down all the old houses and building parking lots.’ That must have been about ’65, right after I met him, and it was basically him and I. Most of it was in Austin, some was in Dallas, mostly him shooting it and me helping him. He edited it together and it won some awards.

Richard Kidd: In the ’60s Ron was kind of a guru to Tobe. Tobe was a great cinematographer, had a really good eye, but he loved collaboration, which Ron really provided him with — they’d talk over shots for hours, figure out some crazy way to rig the camera, hang the lights, whatever. They just went out and shot Down Friday Street, I don’t think they even had a sponsor. When I saw it, that’s when I wanted to get hooked up with Ron and Tobe. I thought it was great — these were the kind of guys we needed to be working with.

Sallye Richardson: First there was Peter, Paul and Mary [a documentary about the folk singers], which was almost a movie, then there was Eggshells, which was almost a movie...

Fred Miller: [Peter, Paul and Mary] was directed by Tobe Hooper and mainly shot by Tobe and Ron Perryman. Their heroes were D. A. Pennebaker and the Maysles brothers. We set out on a venture budgeted at $500... There was only one company doing film in Austin at the time, Motion Picture Productions of Texas, owned by Richard Kidd. Tobe, Ron, and Gary Pickle were part-owners of that company and they became the crew. We started that night in San Antonio... For six months we toured together and shot about 100 hours of 16mm film. Tobe and Ron edited and sculpted the show. I only had a feeling of what it should be like. They knew how to make cinéma-vérité movies. They taught me. [The Austin Chronicle, Dec 1999]

Richard Kidd: I was very much involved in that one. We used three cameras on that, I shot one, Tobe one and Ron shot one. That’s actually a wonderful documentary, it was an hour long, a classic ‘follow them around the country’ kind of deal, paid for by a crazy guy on his credit card: he was an assistant minister of the Baptist Church in Austin. Fred and I knew each other somehow, he came down to the office — he didn’t have any money but he had credit cards, so I went along with that deal and said, ‘OK, as long as you can cover all the expenses we’ll participate,’ and that’s how it got done... We must have shot half a dozen concerts round the country, interviews, the whole bit... There was concert footage and interviews with the three principals, either backstage or at home. It probably still exists in the vaults of PBS [Public Broadcasting System]. It was great.

Eric Lasher: Tobe’s actually in the movie a bit because there are two cameras and he’s on stage and there’s some feedback going on during rehearsal and they’re asking him if he’s responsible — ‘Oh no, not me!’

Robert A. Burns: And then Tobe had this strange film called Eggshells. It started off as a documentary-type thing about some folks living in ‘hippiedom’ — and of course this is after hippiedom really ended and the people weren’t particularly hippiesque, just living together in a house... After they’d shot a ton of stuff, they decided to inject a story and it was made up as it went along. It was neither fish nor fowl, but they decided to try releasing it as a feature.

I was doing a lot of advertising things and he came to me and I ended up putting together a press book. Eggshells showed in like two places... It was just this kind of odd little oddity, there would be some kinda time capsule-esque aspect to it now maybe. Some of this stuff has become campish, but this was just odd. It has some moments of creativity but basically it’s this pointless thing. It would have more nostalgia value in Austin than elsewhere, ’cause it shows things that aren’t there any more.

Mahlon Forman inEggshells.

Lou Perryman: So Tobe brought Eggshells in. I was a hired hand — they provided me with a Volkswagen van full of beer, and every day I went to the movie, ‘What are we doing now?’ I’d load the magazine, carry the camera, set the camera up, charge the batteries — it was basically just him and me, they added other people as the film went on. I think Ron shot a few things, maybe helped out with some stuff.

Tobe Hooper: It’s a real movie about 1969. It’s kind of vérité but with a little push. Like a script on a napkin, improvisation mixed with magic. It was about the beginning of the end of the subculture. Most of it takes place in a commune house. But what they didn’t know is that in the basement is a cryptoembryonic hyperelectric presence that managed to influence the house and the people in it. The influences in my life were all kind of politically, socially implanted. [Interview with Marjorie Baumgarten, The Austin Chronicle, 27 Oct 2000]

Tobe Hooper: ... some sort of strange presence enters the house and embeds itself in the walls of the basement and grows into this big bulb, half electronic, half organic. Almost like an eye but it’s like a big light. It comes out of the wall. It manipulates the house. Animates the walls. Anyway, that’s sort of what it is. I think that the film is a mixture really. It has sort of a Paul Morrissey look at times, like Trash, and other times it has a Fantasia look. [Interview by Donald G. Jackson, The Late Show fanzine, 1975]

Richard Kidd: I was trying to keep the business functioning, actually bring money in the door, pay salaries. So I would go out and find advertising agencies that would pay for commercials, sponsors who’d pay for documentary work. Of course what Tobe wanted to do was produce theatrical things, so there was this constant conflict — you know, ‘Of course, Tobe, but who’s paying the bills?’ He never got anybody with any money! The concept of raising money was totally lost on him! He wanted all the cameras, editing and lights that a business offered, but he didn’t want to go out and shoot that nasty commercial stuff! So for a few years we’d alternate between people trying to come up with an idea they could sell theatrically or to television and in the meantime do the local bank commercials that were paying the bills.

Ben Skabarsak (Ron Barnhart) acts coy.

So Tobe found someone in Houston with a bit of money, God knows, probably an oil and gas guy, and he agreed to fund just the cost of film and processing. We supplied the equipment and editing and some of the crew. I went on some of the shooting, but I never could get too excited about it, it was pretty weird: the story of a couple of young kids Tobe had recruited from the university who have this ‘out of mind’ weirdo experience and go through all this psychedelic crap! So it was the classic late ’60s/early ’70s head trip [laughs]. That was shot in 16mm, but I don’t think it ever got picked up and shown.

Allen Danziger: I think about twenty people saw Eggshells! You’re not missing much... My involvement came about via the couple the movie was originally centred on, David and Amy. Then Kim Henkel got involved and another couple. I had met David and Amy when I was doing social work here in Austin. They got involved with programmes I was doing to get rights for poor people, welfare recipients. Sallye Richardson and her boyfriend Jim Schulman lived downstairs for a while, and Sallye knew Tobe, so I met Tobe through her and Jim. We started talking and when they found out that David and Amy were involved with my programmes they asked if they could do a scene of them coming in and talking with me — I guess you could say cinéma-vérité, no lines, they just said, ‘Here’s the scene, they’re coming in to talk to you’ and let the cameras roll. And that was the start. After that, they asked if I would do another thing — there was a big anti-Vietnam war demonstration going on and they shot some stuff with me there. And also at the wedding, where they got married in the park, I think I’m in that. My son, who was about eight months old, was in it, and my wife Sharon made him an Uncle Sam hat. I have a picture somewhere of him in that car with the bubble on top... It was a bizarre movie.

Sallye Richardson: Allen and his wife Sharon lived underneath us — we had a duplex, my husband and I lived upstairs. That’s how Allen got involved in Eggshells — he met Tobe through us. Tobe liked his looks and he did it for very little [laughs]...

Tobe Hooper: It was a very low-budget film, maybe $40,000 or $60,000. I shot it in 16, and blew it up to 35mm. I remember loading it into the trunk of my old MG, and thinking that it was quite an accomplishment... It’s a film about the disintegration of the peace movement, toward the end of the Vietnamese war. [Fangoria 12, 1981]

Sallye Richardson: I think it cost about $40,000. But I don’t think it ever got distributed — it got a distributor, but didn’t get shown... I believe it was Eggshells we shot some morgue footage for. We went to Houston and we rented this place where they take you when you’re dead to take the blood out and stuff, ’cause we couldn’t find one in Austin. And we got this guy, like a guy off the street, who agreed to be the dead person and lie on the slab ’cause nobody wanted to do that. I think Tobe paid him $100... I remember shooting in that place — it wasn’t very much fun at all... But I don’t think he ever cut it in. It was supposed to be part of the beginning.

Lou Perryman: In a morgue? Yeah, I was there... It was a sidetrack that was not useful, it didn’t make it into the picture. Tobe was fishing for a film in all this material that he had in front of him... There was some guy who had showed up, I’ve forgotten his name or how he showed up, he was kind of a hippie character. And Tobe decided he’d been killed in a motorbike accident or something, and the next thing we were down in a funeral home outside Houston. So we shot a fake embalming process, where you see them open the carotid artery and the blood drains out and then the embalming fluid goes in — it was fairly ghastly...

There was an interesting scene where we shot two of the actors literally fucking — but it was not shot explicitly. It was a closed set, just me and Tobe and the two actors. I was holding this frame with some mirrored mylar on it and Tobe was shooting into the mylar and I was giving him a distorted reflection of their coupling...

Spencer Perskin: I can’t remember when I first started hanging out with Tobe at his office where he did editing — at the corner of 8th and Nueces, I think. He mostly did short films in those days, but had plans for feature length films, too. When he finally was ready to make Eggshells he gave me the opportunity to do music for it. I wound up doing about half the soundtrack, some on sitar with Jim Franklin tapping tablas, some with Shawn Siegel... We appear in the movie as Shiva’s, playing for a wedding which is actually taking place there at the gazebo in Wooldrige Park by the courthouse. However, you don’t hear the band in that scene. We went up to Robinhood Brian’s studio in Tyler to do the music. Tobe told me we were doing sitar so I brought Jim with me because he had some tablas and could play a little. We did some sitar stuff, and I think some other solo stuff. Then, all of a sudden, Tobe says, ‘Where’s the band?’ and I say, you never said bring the band. But Tobe wanted some rock’n’roll so I called Shawn in Austin and said, ‘How soon can you come?’ and he said ‘Pretty quick,’ because Tobe had dough. So when Shawn showed up, it being a good six hour drive to Tyler from Austin, we did our usual pre-game warm-up and then went right to work. Tobe needed some rough raucous rock and we just had the two of us, so Shawn did piano and organ and I threw on drums, bass, guitars, and, if I remember correctly, some fiddle. We did my instrumental piece, ‘Thing in D’, to which a Volkswagen is blown up in the movie, too cool. [From ‘Stars We Are’, on Spencer Perskin’s Shiva’s Head Band website]

Wayne Bell: Tobe and I were friends. I was a college student and I worked on Eggshells. I had known Tobe before that, when I went to work, right out of High School, for the film production company MPP, later called Film House, here in Austin, of which Tobe was a co-owner. Two of the guys there — Tobe Hooper and Ron Perryman — were very talented and I naturally gravitated towards them. And that’s how Lou got into the film business — through his brother recruiting him. Lou came up and began to get to know cameras. This would be the summer of 1969 — although shooting began on Eggshells in the fall of ’69, my first involvement was in summer 1970.

Levie Isaacks: When I was at UT we turned out 25,000 students against the war in Vietnam — it was pretty much unheard of that that would happen in what had always been considered a pretty conservative city.

Wayne Bell: The protests against the Vietnam War really went onto another level around that time. There was a massive peace march in Austin and this TV station I was associated with at college sent me down to do some coverage and I ran into Tobe. They were filming these — hippies basically [laughs] — so I got in with them and helped out, and we filmed the rest of the day. Then I ended up spending my summer working on Eggshells. My guess is that a lot of the more pedestrian stuff was shot during the preceding spring — people hanging out, you know. A lot of that stuff was basically improvised — I’ve listened to a lot of the audio, the synched sound that was done — there was no script, it was, ‘Here’s the set-up here, see if you can get it to there.’ And there were definitely some non-actors. Kim had a girlfriend named Mahlon and they were both in it. They had this great old painted car with a bubble on top. One of the first shots I did was a scene out in the country where they blow up the car. The car ‘evaporates’ — it was on a platform over a pit and when the puff of smoke goes off, the platform blows and the car disappears. That was the idea.

The wedding in the park.

Boy, was it a character doing the explosives — Henry Holly [laughs] — oh man. Being the kid of the group I got stuck driving with Henry and his shrieking wife, dragging a trailer full of explosives. They were haranguing each other and the car was swerving back and forth — at one point we did a ‘gas and pee stop’ — and I got out of the car and went over to the van with Tobe and the others, got in and said, ‘I’m riding with you.’ And nobody questioned it. Henry had a reputation... The ride back was great, and we really got to know each other.

Shortly after that we would get into these jam sessions. I come from a musical background, whereas Tobe and Ron were non-musicians but very creative guys. So we would play together, just experimenting with all kinds of instruments: dul-cimers, percussion instruments, children’s toys, some electric stuff — there weren’t really synthesizers then. Some of that music is in Eggshells. There’s a lot of other music written by songwriters, and other players as well, so the score is quite eclectic. There are a few places where the score gets kind of strange... I don’t know that any session I played on is in Eggshells — Tobe and Ron would also have these jam sessions when I wasn’t there. And that was the precursor to the Chain Saw music.

Eggshells in a way was dated the moment it came out — so tied to a particular time, not only in the things happening on screen but the whole mindset, and it’s going to look laughable and quaint at different times because it’s so ‘of its time’...

Lou Perryman: I think Tobe gave me an assistant director credit on Eggshells. It was supposed to be a movie about two sweet sort of hip kids in college that the producer Dave Ford knew, and Tobe took it crazy from there — ‘Hmm, they’re going to watch it for about five minutes if it’s people sitting around eating wheat germ, hell’ and so he began to add these fantasy characters. That’s where he met Kim... It was a hippie movie about people that were hip and smoked dope and lived this alternative lifestyle and had various crises... I think it was sold as some sort of tax write-off, so it’s basically never played again.

In the culmination of the picture, Kim goes off in this old car with a bubble on the top, it’s all painted up like the American flag, takes it out in the middle of this field, sets it on fire, throws his clothes in and runs away nekkid, then the car blows up.

I remember on that shot, at the last minute somebody handed me a Nagra [tape recorder] and said, ‘Go get some sound,’ and I went over and got behind these bushes and got ready to turn it on then thought, ‘That guy said something about not starting any electric motors, aren’t these electric motors in the recorder? But my God, I got to get some sound but I can’t turn on the motor...’ Finally I decided I had to get the sound and turned it on, and the instant I turned it on, the explosion went off, I thought I set it off! The car was over a pit which it was going to drop into, then the explosion and gas would go up in line with the camera so it looked like the car blew up — the platform they’d built was not the right width for the tyres, so it looked really cheesy getting the thing on. And the dynamite, like twenty-five sticks of it, was already in the pit and I think there was another seventy-five with the gas. And to get the car onto this thing, we had to pull it with a rope, and so somebody had to steer it. So I ended up getting in the car or leaning over into it and steering it while it went up on the ramp, leaning over this dynamite pit...

Sallye Richardson was involved in some way — it was hard to tell what anybody’s particular job was — you know, it was just put together that way... I do remember Sallye being out there when we blew up the car, that was excellent...

Sallye Richardson: I took all the photos — including the one on the poster, the boy and girl in the bubble — seems to me I took that when we were out blowing up the car. That was the first time I’d ever blown up anything, it was real exciting. I think Ron was doing that too — we had three cameras there, maybe four, it was a lot of fun.

Richard Kidd: I remember seeing some of it in editing — we’d all collectively hold our noses at how bad the two kid actors were — it was pretty terrible from that standpoint. But it did have a gigantic big car explosion. The two hippie kids drive their painted-up old car into the country, to the woods, then they walk away from it, and as they walk away it magically explodes and disappears. Tobe had this great idea, and Ron helped him rig it, where they dug a hole about twelve feet deep then put two by fours together and rolled the car out over the hole, with fifty gallon drums of gasoline and explosives under it. For the big scene I was shooting one of the cameras, we’d gotten three or four together to do it — as Tobe pointed out, ‘Hell, we only get to shoot it once!’ Then they trigger the explosion and the car disappears in a puff of mushroom-shaped cloud, drops down into the hole — it was a great-looking special effect, but, you know, we’re probably lucky nobody got blown up! [Laughs]

In 1971, Tobe Hooper and Jim Siedow both acted in The Windsplitter, a low-budget exploitation number also produced by David Ford. Bobby Joe Smith, a small town boy-turned movie star, returns to his home town with long hair and motorbike to encounter Easy Rider-style prejudice and violence. Hooper played one of the Wilson Brothers, local thugs who take a dislike to Bobby Joe. Mahlon Forman, Kim Henkel’s partner at the time and another Eggshells veteran, also appeared.

Kim Henkel: I was a grip on The Windsplitter, that’s where I met Ron Bozman, who became the production manager on Chain Saw. He was my fellow grip in some cases, most of the time he was the assistant cameraman. If it got a release beyond David Ford going around booking it into a couple of theatres himself, I don’t know. I think David Ford just never had a great deal of judgement when it came to material [laughs]... You know, you have to remember that I took the screenplay of Chain Saw to him and offered him the opportunity to be part of it and he declined...

Sallye Richardson: I was assistant director on The Windsplitter, I shot the one-sheet as well — it was funded by Dave Ford, the director was J. D. Feigelson, and it had an LA cinematographer and lighting crew. We shot it in a little town outside Houston, but I don’t think it ever got much distribution. Jim Siedow played the father of the girl, and Tobe was in it: there are these three goofy guys who get everyone in trouble — he was one of them. I think Tobe always wanted to be an actor too; he was very enthusiastic. He and J. D. were kind of friends at the time, partly because of Dave Ford being the money man behind both their movies. It had local backdrops — there’s a scene in a local bar, but it’s more like a little place where old guys go to play dominoes — with real locals. It was a very historic little town.

Jim Siedow: I didn’t know Tobe back then. The Windsplitter was shot in Columbus, about thirty miles from Houston. When it came to making Chain Saw — the unions had some kind of deal where you can make a movie if there’s a SAG member in the cast and a SAG technician. So I was the SAG actor that Tobe got to be in it — I was the only professional actor.

Tobe Hooper: Kim was one of the actors in Eggshells. That was how we met, and as we worked together, Kim helped to develop it. Eventually we came to be collaborators on the script. Following Eggshells, we worked a year or so together, and worked out the specifications on several projects; finally we came up with Texas Chain Saw. [Fangoria 23, 1982]

Kim Henkel: I acted in Eggshells — well, after a fashion — and that’s where I ran into Tobe. I wrote some short little pieces for it. It was mainly centred on two friends of mine — and it was because I knew them that I ran into the whole situation. After that, Tobe and I talked about something off and on for several years and then we finally settled on the Chain Saw project. Then we spent most of six to eight weeks one spring beating it out.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

“WE JUST WANT TO MAKE SOMETHING FOR A BUCK”

Tobe Hooper: The true monster itself is death. All the classic horror flicks — Dracula, Frankenstein, Psycho — have this in common. They have a unique way of getting inside you by setting up symbols that represent death: a graveyard, bones, flowers. If you put them in the proper order then you create the most important aura known as the creeps. [The Texas Monthly Reporter, March 1974]

Tobe Hooper: It’s a film about meat, about people who have gone beyond dealing with animal meat and rats and dogs and cats. Crazy retarded people going beyond the line between animal and human. [Bryanston press notes]

According to Tobe Hooper, the genesis of the Chain Saw legend runs as follows: one Christmas he found himself in the hardware department of a large branch of Montgomery Ward’s, brooding about a film project and cursing the holiday period crowds, when his attention was drawn to the chainsaws as a useful aid to a hasty exit... After escaping the crowds and store, the whole concept for Chain Saw then apparently manifested itself to Hooper in thirty seconds!

Tobe Hooper: The structural puzzle pieces, the way it folds continuously back in on itself, and no matter where you’re going it’s the wrong place. That was influenced by my thinking about solar flares’ and sunspots’ reflecting behaviours. That’s the reason the movie starts on the sun. It’s amazing how it all kind of zeitgeisted into my head so quickly. [The Austin Chronicle, 27 Oct 2000]

Lou Perryman: I think Tobe starting getting the idea about chainsaws when I was living like a hermit with another fella out in the woods — we had a chainsaw and a lot of stumps, and a wood-burning stove, that was the only way we could heat ourselves. So I had this chainsaw and he was terribly scared of it: ‘Oh God, be careful with that chainsaw, be careful with that chainsaw!’ The next thing I know, I’d moved to Colorado and he and Kim had written this script, Headcheese as it was called...

Tobe Hooper sets upChain Saw’s climax.

Tobe Hooper: The old EC comics were collections of short horror stories... They were absolutely frightening, unbelievably gruesome. And they were packed with the most unspeakably horrible monsters and fiends, most of which specialised in mutilation... I started reading these comics when I was about seven. I loved them. They were not in any way based on logic. To enjoy them you had to accept that there is a Bogey Man out there... Since I started reading these comics when I was young and impressionable, their overall feeling stayed with me. I’d say they were the single most important influence on The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. A lot of their mood went into the film, along with some of Hitchcock’s methods of manipulating an audience. [1977 interview with Glenn Lovell and Bill Kelley, Cinefantastique, Oct 1986]

The brush with Christmas crowds, chainsaws, horror comics, the hippie hangover of Eggshells, and the legend of Wisconsin ghoul Ed Gein (see page 238) combined and ignited with whatever else was happening in Tobe Hooper’s head to provide a spring- board. In what would prove to be one of the great collaborations of horror cinema, Hooper teamed up with Kim Henkel, and the twosome began to hatch a plot...

Kim Henkel: The initial idea was both of ours, though maybe I would say more Tobe’s than mine if I had to split hairs about it... But what we did was sit down and talked through the script, worked through it scene by scene in terms of action, what was going to happen from one scene to the next, then I would go off and write the scene.

Bob Burns knew Gunnar Hansen. I knew Ron Bozman from The Windsplitter and had a lot of confidence in him — I knew we needed someone who could really organise things, because we were dealing with a lot of people who were not particularly good in that realm. So I talked him into coming down and doing that. He did his best given that harem scarem crew of people...

Robert A. Burns: The people involved in Chain Saw were local except for a couple of friends of Tobe’s (Jim Siedow and a couple of crew). Ed Neal was the only one I knew previously — we had crossed in the drama department at the University of Texas years before — I didn’t know him real well but he was the only person I had met before, cast-wise... The crew was all out of UT’s film department — everybody wanted to get the credit and experience, like you do when you’re just starting out, and it’s amazing how many members of the crew have gone on to very successful careers in film-making.

When it came time to do Chain Saw, I had known Tobe for eight years; I was the person to do art direction ’cause Tobe knew what I did, and I had a well-established reputation for being able to make something out of nothing. I’d put things together and taken them apart all my life. I had a large old office where I did graphic arts and advertising — and there was no production office, so we did the casting out of my office ’cause I had a lot of space there.

Tobe and Kim came here and brought this script and said, ‘Let’s do it’ and I was familiar enough with Tobe to know that he’d fling himself into something and it’d become the be-all and end-all. So I was a little cautious but they said, ‘Don’t worry, we just want to make something for a buck.’ But ultimately he did end up flinging himself into it and it became nightmarish...

Richard Kidd: Tobe and Ron were such a creative, energetic team you didn’t want to lose them. They were working at Film House up until Tobe got the Chain Saw money together. I made a deal to supply equipment to them on a rental basis, I think it was a half money, half credit kind of deal. At that point Tobe was soliciting the help of anyone he could, everybody he knew. We owned three Eclairs, and they were always Tobe’s favourite camera so he couldn’t stray too far from our cache of goodies! We didn’t have a colour lab though, the film had to be sent to Dallas. We could do sound mixes and editing and of course we had lighting and film gear, but we didn’t have any processing. As I remember he wound up putting together two or three different deals — he wanted some things we didn’t own, like dollies. And we couldn’t let our gear go all the time ’cause we were trying to do the other stuff, so there was another rental company up in Dallas that was supplying him as well. But Tobe was really a very lousy business person — he was a great, creative ideas guy, but as far as business was concerned...