Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Paul McCartney has often initiated and participated in projects that have taken him a long way from the kind of music associated with The Beatles, Wings and his work as a solo artist. These projects include the psychedelic tape loop experiments of the 1960s, the 'Percy Thrillington' diversion in the 1970s and more recent albums recorded, as 'The Fireman' — as well as even more obscure activity, much of which this book reveals in depth for the first time. Ian Peel has interviewed many of McCartney's intimate musical associates from this less familiar side of his career. These include Youth, Super Furry Animals, Nitin Sawhney, playwright Arnold Wesker and, perhaps most surprisingly of all, Yoko Ono. What emerges is a unique insight into an apparently over-familiar public figure—Paul McCartney, experimental musician.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 562

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

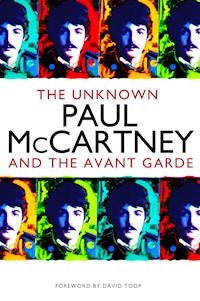

THE UNKNOWN PAUL MCCARTNEY

McCartney and the Avant-Garde

Ian Peel

TITAN BOOKS

The Unknown Paul McCartney

McCartney and the Avant-Garde

E-book ISBN: 9781781162750

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: April 2013

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2002, 2013 by Ian Peel. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

For Kristianna

CONTENTS

Foreword by David Toop

Preface

Acknowledgments

1. Brass Bands, Vinyl and Pigeonholes

2. Influences, Memories and Beatles

3. Carnival of Light at the Fantasy-Loon/Blowout/Drag Ball

4. From Vegetables to Llysisu (and Back)

5. Music Made with Moogs and Glasses

6. “An Abundance of Melody” as Easy Listening Fights Back

7. From Sheep Masks to Pseudonyms (and Baa)

8. Music Made with Radios and Gizmotrons

9. The Chapter Nine Remix

10. It’s a Long Way Off the Frog Chorus...

11. In the Studio with Yoko Ono

12. On Stage with Allen Ginsberg

13. Crossing the Bridge to Palo Verde

14. From Steel Towers to Siegen (and Balaclavas)

15. Reel Gone Dub Mede In Manifest In the Vortex of the Eternal Now

16. Music Made for Families and Neuroses

Epilogue – A Blind Tasting

Appendix 1 – Listening

Appendix 2 – Further Listening

Appendix 3 – Selected Articles and Websites

Appendix 4 – Bibliography

Index

FOREWORD

By the end of the 21st century, the cultural schematics we use today will look very quaint – a bit like those antique maps that would fill some vast area of uncharted territory with a drawing of a poorly observed rhinoceros or spouting whale. Terms such as avant-garde, popular, classical, highbrow, lowbrow, mainstream, middle-of-the-road and experimental began to sound bleached out and pointless during the 1960s. Too many movements, individuals and events contributed to that seismic shift to be named here, but The Beatles were as important as anybody.

They created a happy confusion of perception whereby a single record could be appreciated on many different levels without harming either its sales, its artistic impact or coherence. All those genres that recoiled from miscegenation seemed legitimated and somehow socialised within a Beatles album. There was a party. Carl Perkins, Smokey Robinson, Bob Dylan, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ravi Shankar and The Goons were invited. There were tensions and arguments but by the end of the night, everybody agreed that they had a good time.

Though Lennon and McCartney could write unforgettable songs at a rate that was almost supernatural, they played with sound within each song. Arranging, to use an old-fashioned word, seemed to be an innate skill for all four Beatles. That organic relationship between sonics and structure, reinforced by the experiences of George Martin, led them to electronic music, free improvisation, performance art, minimalism, loops, ambient sound, world musics, collage and noise.

Underestimating the importance of those discoveries is impossible. Composers such as James Tenney, Toru Takemitsu and Terry Riley had sampled and collaged popular musicians to remarkable effect but, even now, their efforts in that area are barely known. Whatever The Beatles did was an event of huge proportions. A general conception of what was possible, or acceptable, was amplified to a similar scale and the influence continues to be felt.

Some of the walls broken down in those heady times have been rebuilt. Somehow it’s difficult to imagine a band as complex, versatile and utterly essential as The Beatles existing now, and besides, experimentation no longer has the same impact. Inevitably, an extensive mythology has accumulated since the 1960s. Understanding the events of that time, their context and the interrelationship of all the characters involved demands research that goes beyond that mythology, along with its deeply rooted images and icons.

What did it mean, chewing vegetables with Brian Wilson? In his various guises and disguises over the years, Paul McCartney has suggested some answers to that question. The chewing, the nature of the question and many of the answers are documented in the pages that follow.

David Toop

author of Rap Attack, Ocean of Sound and Exotica

August 2002

PREFACE

I remember once saying to John that I was going to do an [avant-garde] album called Paul McCartney Goes Too Far. He was really tickled with that idea. ‘That’s great, man! You should do it!’ But I would calculate and think no, I’d better do ‘Hey Jude’.

Paul McCartney on Radio 1, 1990

You won’t believe what you’re about to hear. Or if you do believe it, you might be surprised at who you are hearing it from. This is the story of Paul McCartney’s sound experiments and pseudonyms, from tape loops to trance.

“Ballads and babies. That’s what happened to me,” is how Paul McCartney summed up his post-Beatles career in a 1970s interview with Time magazine. It was later used as the closing quote of a McCartney biography in 1997, but actually makes the perfect opening for this book, which extends the artist’s story a million miles from the ballads, the middle of the road and the rock and roll he is synonymous with.

Since the mid-1960s, Paul McCartney has explored various different fields of avant-garde music on albums, singles, remixes, soundtracks and live performance. Almost every one of these has been carried out either under a pseudonym or completely anonymously, rarely if ever under the name Paul McCartney. Why is this? What avant-garde music has he produced? What are the musical inspirations behind this work? And what are his motivations in continually dabbling away from the mainstream songs he is most famous for?

The Beatles’ musical experiments have been examined to death. But from there on in it’s uncharted territory. Between MacDonald, Miles and The Beatles Anthologyyou have all you need to build a picture of the 1960s, The Beatles and (most of) their avant-garde work at the time. This book continues the story, connecting all the experimental ideas from that period against a backdrop of influences from the decades before, and linking them to McCartney’s work from 1970 to the present day.

The Unknown Paul McCartney doesn’t set out to paint the artist as being seminally important to the avant-garde. It merely aims to put the experimental ten per cent of his music into the frame. Experimental composers such as Stockhausen and Cage are often mentioned as influences on The Beatles in the psychedelic era. But these and many other musicians, sounds and ideas from the left field of music continue to influence McCartney to this day.

In 1969, McCartney and Ringo Starr were the only Beatles who hadn’t released avant-garde solo albums. Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Unfinished Music No. 1/Two Virgins was already infamous. One hour of screaming, electronic effects and tape loops. It was followed by more madness in music – Unfinished Music No. 2/Life with the Lions and The Wedding Album. In 1969, George Harrison released Electronic Sound – a full album’s worth of his (and other people’s) Moog synthesiser test-recordings. This followed the early world music of Harrison’s Wonderwall Music film soundtrack.

Although equally active in the underground experimental scene, McCartney’s work was less visible during the sixties. By 1970 the other Beatles had all but abandoned their avant-garde experiments, but McCartney was just getting started. All the influences he picked up in the psychedelic era leaked out from both his solo work and obscure Wings recordings until, in the 1990s, he embraced his avant-garde side and a flood of collaborations and recordings emerged, ranging from freeform post-rock to chill-out.

As his solo career has progressed, Paul McCartney has become increasingly cautious about what music he has released under his own name. Across the past three decades his work has become more and more wide-ranging, but the material that reaches the public under his own name has trodden the middle ground. It’s only when you assess the work of Paul McCartney, The Fireman, Percy Thrillington – and his myriad collaborations and hidden tracks for art shows, B-sides and film soundtracks – that you get a full picture of this diverse musician.

McCartney’s non-mainstream collaborations are full of surprises. His collaborators include techno/trance producer and founder of The Orb, Youth; Anglo-Asian drum & bass fusion maestro, Nitin Sawhney; Welsh art rock experimentalists Super Furry Animals. To say nothing of a wiggy night-time session with Brian Wilson, a transatlantic rhythm track with Allen Ginsberg and a freeform jazz/rock improvisation with the person you’d least expect McCartney to collaborate with on anything – Yoko Ono.

Major works of official McCartney biography invariably get labelled as either revisionist or propaganda. (“He rewrites history all the time,” said Beatles biographer Philip Norman of McCartney in 1987.) Such is the problem of covering an artist who is, on one hand, of vital importance to 20th century music and, on the other, a living breathing human who juggles celebrity with creativity. Rather than pump propaganda (either for or against), all I hope to do in these pages is describe the music I’ve heard and investigate the influences and processes behind it. As a result, McCartney’s story might be seen from a completely new standpoint and the rest of his musical oeuvre might be cast in a new light.

For a period after John Lennon’s death (and his immortalisation as rock, and avant-garde rock, guru), McCartney became paranoid. He started making statements about his avant-garde work, questioning who dipped their toes into experimental waters first. In the final analysis, The Beatles’ most well-known avant-garde composition is Lennon’s – ‘Revolution 9’ – to say nothing of his random radio broadcasts in ‘I Am the Walrus’ and his backwards vocals in ‘Rain’. Curiously, schizophrenically even, while McCartney the Public Figure was making these statements, McCartney the Private Musician was beavering away making new experimental tracks with no intention of releasing them under his own name. “He’s a very interesting musician,” says author and guitarist Lenny Kaye. “Certainly he has the wherewithal and the range to try anything and I respect him for that. Even though the general categorisation of John being the radical one and Paul being the pop one is kind of widespread, I remember that in actual practice, they took each other’s place in the mirror many a time.”

There’s another potential by-product of both this book and McCartney’s avant-garde musical experiments: some fascinating, out-there genres and musical ideas get put in front of a whole new mass audience. McCartney made his key instrument – the left-handed Hofner violin bass – a musical icon in its own right. This book adds quite a few new, unexpected instruments to the list: olive oil, tape recorders, carrots, pots, celery, radios, apples, glasses, toilets, car horns, twigs and chainsaws. To say nothing of technology. Odd inventions like the ‘watery box’ and the Gizmotron. Or tools like turntables and samplers, Akais and Mini Moogs – not the kind of gear readily associated with an artist whose first major 1990s album was Unplugged.

Tracing the history of the experimental music these odd instruments represent is incredibly subjective. Unless you have a yardstick. How do you know what’s off the beaten track, or left of centre, if you haven’t established where (or who) the centre actually is? So as well as tracing the ‘unknown’ McCartney, the book also traces some of the strands of alternative music from the sixties to the present day. The fact that Paul McCartney has a wealth of relatively unknown avant-garde inspirations and collaborations offers the chance to explore an abstract story (the last 40 years of avant-garde rock) with a familiar central character.

Paul McCartney’s music – both with The Beatles, Wings and solo – is like a permanent radio, soundtracking our daily lives. Another hypothetical FM station is growing up with his classical music. But coming in on the short wave are these avant-garde transmissions. They begin in the psychedelic era with tape collage, both with and outside of The Beatles, and McCartney’s interest in electronic music. These early experiments and the cast of characters and events that inspired them are explored in Chapter 2: ‘Influences, Memories and Beatles’. That is, after we have caught up with McCartney’s life story and formative influences in Chapter 1, which revolve around ‘Brass Bands, Vinyl and Pigeonholes’. One of The Beatles’ great lost avant-garde works, ‘Carnival of Light’, is explored in Chapter 3. “More nonsense has been written about this recording than anything else The Beatles produced,” wrote Ian MacDonald in 1994, so this chapter adds some sense and first-hand accounts to the equation.

You could be forgiven for thinking that the avant-garde world – inhabited by unsmiling performers such as AMM and space-age scientists like Delia Derbyshire – was an intensely serious environment. But some people can question the very nature of music or rhythm with a smile or joke as opposed to a lecture. A musical suite performed on gynaecological instruments pops up in Chapter 3. Then, enter the First Vienna Vegetable Orchestra who talk with the Super Furry Animals about McCartney’s vegetable-chewing music in Chapter 4, ‘From Vegetables to Llysiau (and Back)’. Llysiau is Welsh for vegetables. All will become clear...

Two chapters were originally planned to ‘bridge’ the investigations of the major works and provide some kind of timeline. One covered the 1970s, another covered the 1980s. But the more I dug around, and listened, the more I heard traces of the avant-garde inspirations and influences from the early chapters. I spotted the seeds of McCartney’s relatively recent, prolific experimental output being sown too. So Chapter 5, on the 1970s, became ‘Music Made with Moogs and Glasses’, a history of Wings viewed from the left field. Chapter 8, on McCartney in the 1980s, became ‘Music Made with Radios and Gizmotrons’ and unearths some off-the-wall gems from what is generally regarded as his most lacklustre period.

Between The Beatles and Wings, McCartney flew off in another odd direction, embracing easy listening and exotica to produce Thrillington, an instrumental lounge version of his rocky solo outing, Ram. Some of the production techniques and sounds on there were avant-garde but the music was its complete opposite. So why does it qualify for this book? Well, it’s ‘unknown’ to the mainstream market and was certainly experimental. It has influenced some avant-garde musicians since its limited release. And muzak-style music, which is what Thrillington borders on, is also one of the strongest roots of ambient music, a modern development of the work of 1940s and 1950s avant-garde composers. It also fits in with almost all McCartney’s full-blown experimental output in that it was released not under his own name but under an elaborate smoke screen and pseudonym. These and McCartney’s other attempts to hide from the public eye and watch his music succeed on its own merits are surveyed in Chapter 7, ‘From Sheep Masks to Pseudonyms (and Baa)’.

Avant-garde as a genre began in the 1940s with some of the composers explored in Chapter 2. At that time, making music with turntables and electronic devices was cutting edge. Further out than that even. Nowadays it’s probably just as common as making music with a guitar. These two worlds crossed over in the 1980s in a unique space which grew between song and performance, as Chapter 9, ‘The Chapter Nine Remix’, explains. From the 1990s onwards McCartney has embraced his avant-garde leanings while at the same time some of these styles have become mainstream, transforming into techno, ambient and chill-out. Techno might be a daily staple for McCartney’s children’s generation, but for a rock and roller they’re still cutting edge. Some of the other styles he has explored remain truly avant-garde, like minimalism, post-rock, random orchestrations and pure industrial noise.

Chapter 10 examines McCartney’s first foray into techno and dance territory as The Fireman, a duo comprising McCartney and dance producer Youth. ‘It’s a Long Way Off the Frog Chorus’ indeed. Chapter 13, ‘Crossing the Bridge to Palo Verde’, covers the second Fireman album, an ambient epic. The third album in this series wasn’t credited to The Fireman, as other players were involved. Peter Blake and the Super Furry Animals joined McCartney and Youth in remixing art into music and drawing long-overlooked parallels between sound collage and pop art. The result is Chapter 15, ‘Real Gone Dub Made in Manifest in the Vortex of the Eternal Now’.

McCartney’s songwriting collaborators after John Lennon, the likes of Denny Laine (for Wings), Eric Stewart (for Press to Play in the 80s) and Elvis Costello (for Flowers in the Dirt in the 90s) helped him come up with some catchy melodies and radioplay-friendly arrangements. But it’s his avant-garde/non-mainstream collaborators who have stretched McCartney’s musical mind and produced results close to those he achieved with his first, iconic collaborator. Youth is one and there follow the stories of two other little-known collaborations with artists you wouldn’t expect McCartney to be playing with – Yoko Ono and Allen Ginsberg. Hence Chapter 11, ‘In the Studio with Yoko Ono’, and Chapter 12, ‘On Stage with Allen Ginsberg’.

Not all McCartney’s sound experiments have been confined to obscure vinyl or CD. Chapter 14, ‘Sound and Sound Spaces’, looks at the various bizarre live sessions he has indulged in, far from the mainstream limelight. From continuous 30-minute webcast jams to white noise installed into specially designed steel towers. These are all areas of musical exploration that are relatively alien to his peers. After considering his experimental work at the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 21st century, Chapter 16, ‘Music Made for Families and Neuroses’, considers the artist’s motivations both for experimental work and performance in general.

At the end of Chapter 16, despite hearing the views of musicians and the media on the merits of McCartney’s experimental music, I was left with one nagging question. Is it any good? Or, more to the point, is it any good in the context of experimental music, as opposed to in the context of McCartney Music? To answer this question I staged a ‘blind tasting’, taking CDs and tapes of the recordings unearthed in this book to the studios and lounges of musicians and DJs, all of them renowned in their particular fields, from post-punk experimentalists Wire to Ibiza DJ Chris Coco. We played the tracks and talked about them. And I made sure I didn’t let on that they were listening to Paul McCartney until I’d gathered some frank and very revealing opinions.

The book closes with four appendices. The first, ‘Listening’, is a basic album-based discography of all McCartney’s work covered herein, both mainstream and experimental. The second, ‘Further Listening’, is a lengthy discography of every musician, influence and related performer covered along the way. Musicians like AMM and Cage have often been mentioned in Beatles-related books, but this is the first time a discography has been put together that will actually enable the reader to hear their music. Appendix Three lists ‘Selected Articles and Websites’ that have provided snippets and pointers in the research process and Appendix Four, ‘Bibliography’, provides a list of further reading on the artists and eras covered.

“At his worst Paul is twee,” wrote Chris Fox once in Rubberneck, the UK’s longest-running experimental music magazine, “yet how many are aware that for every ‘Ode to a Koala Bear’ there is a ‘Peter Blake 2000’ (a 17-minute tour de force of looped and distorted dialogue, some taken from Beatles’ studio chat) and for every ‘We All Stand Together’ an ‘Oobu Joobu’?”

If you only hear one Beatles album it has to be Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. If you only hear one Wings album it has to be Band on the Run. If you ask me, the other indispensable McCartney album is Rushes by The Fireman. Yet Paul McCartney’s best and most groundbreaking work of the past 25 years is missing from every biography on the market. Similarly, his other experimental recordings – such as Feedback, Thrillington, Strawberries Oceans Ships Forest and Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue – are completely ignored in every McCartney book I’ve ever picked up and are rarely mentioned in the press. The upcoming 200 pages or so should just about plug the gap.

Ian Peel

Winchester

August 2002

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks first and foremost to Richard Reynolds and Marcus Hearn for their excitement and enthusiasm in bringing this book to life.

Thank you to all the musicians and artists who gave me their time, insights and memories: Yoko Ono, Edwin Prevost, Jerry Marotta, Daevid Allen, David Vaughan, Gruff Rhys and the Super Furry Animals, Laurence Juber, Stuart Howell, Steve Anderson, Steve Silberman, David Mansfield, Nitin Sawhney, Arnold Wesker, Youth, Keir Jens-Smith at Black Dog Towers, Adam Sykes at Iris Light, Natalie Rudd, Tim Cole at SSEYO, Guy Fixsen and Laika, Colin Newman and Post-Everything, Brian Wilson, kG and 8 Frozen Modules, Andrew Poppy, Lenny Kaye, JJ Jeczalik, the First Vienna Vegetable Orchestra (Stefan Kühn, Barbara Kaiser, Mathias Meinhardter, Ernst Reitermaier), Richard Hewson, Herbie Flowers, Mike Keneally, Mike Flowers, Chris Coco, Trevor Horn, Lol Creme.

Thank you also to all the people who helped me connect with the interviewees, many of whom provided insights of their own: Shazia Nizam, Geoff Baker, Mrs David Vaughan and David’s studio colleagues, Robin Eastburn, Julian Carrera, Lindsay Wesker, Darren at Dragonfly, Zak at Big Life, Petrina at Work Hard, Rob Stevens, Mark at deliaderbyshire.com, Jean Sievers, Steve Cohen at Music and Art Management, Bernadette Reitter at the Institute for Transacoustic Research, Karen Foster at the Swingle Singers office. Thanks also to Mark Ellen and the Rocking Vicar, David Hepworth.

And to the listeners, collectors, fans and thinkers whom I have corresponded with. Some have odd, on-line nicknames but all have opened my eyes and ears in some way (or another): Accio; Amrayll, Nowhere Man, cb70, Paul/The Mgnt, Claudio Dirani, Kaikoo Lalkaka, Laila Solum Hansen, Karen Lopez, Nancy, Debbie, Susan, Sue, Cathy (and the Macca-L crowd), Jan Cees ter Brugge, Jorie Gracen, Jonathan Dancey, Chris Hannam, Bill Smith, David Jacobs, Boris Vanjicki, Carol Cleveland, Amy Titmus, Sari Gurney; Pinstripe.

Like this book, Prendergast’s The Ambient Century (Bloomsbury) traces the story of experimental music from Stockhausen to Sawhney but is a road atlas compared to this excavation of one particular path. For dates and facts, two main catalogues were useful and come recommended, namely Madinger and Easter’s Eight Arms to Hold You (44.1 Productions) and Badman’s The Beatles After the Break-Up (Omnibus Press). The former compiles music and the second compiles dates and events regarding the solo Beatles.

Thank you to Mum and Dad for introducing me to music in the first place, to Ken for (musical) inspiration, and to Elisiv for (supreme) motivation.

1

BRASS BANDS, VINYL AND PIGEONHOLES

Pigeonholes can often be comfortable. Sometimes even cosy. But every now and then they get outgrown. Paul McCartney, musically at least, has always had an odd relationship with the one he got landed with. You can trace his predicament back to a yellowed old copy of the New Musical Express, circa 1970: “James Paul McCartney is home and baby and Linda and ballads and rock ‘n’ roll ravers and Fair Isle sweaters and dad and brother and the Friday train to Lime Street,” wrote the NME’s Alan Smith. John Lennon, on the other hand, was “Yoko and Peace and Plastic fantastic; X and Sex; and bang the gong for right and wrong.” These sound like epitaphs, yet Smith wrote these boisterous lines at the beginning of the story this book traces...

From childhood, Paul McCartney experienced an array of musical styles. His father was responsible for his musical education and took him to brass band concerts in the local park, as well as making sure the piano at home was rarely silent. Later, McCartney Jr would play telephone pranks with tape recorders, using rude recordings he’d made with John Lennon when the two were in their early teens. At 11 he won a book token in an essay competition to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. He chose a book on modern art, which provided his first insight into the world of Dalí and Picasso. All of these formative moments went on to influence McCartney’s avant-garde or experimental music as much, if not more so, than his traditional rock and roll songs.

The avant-garde was never knowingly on The Beatles’ agenda. “Avant-garde is French for bullshit,” Lennon famously said. “Avant-garde a clue,” George Harrison added. But in 1966 McCartney – along with Lennon, Harrison and all of the artists he knew – found his mind exploding. The psychedelic era marked the ‘end of the beginning’ of The Beatles. By that stage they’d torn through crowds at the Cavern Club, torn across the Reeperbahn in Hamburg and torn up the charts with the first phase of their album catalogue – Please Please Me and With the Beatles in 1963, A Hard Day’s Night the year after, and Beatles For Sale and Help! in 1965.

By the time this book catches up with McCartney’s life story he is living at his girlfriend Jane Asher’s parents’ house, renting their attic room in London’s Wimpole Street. All of the relationships are in place that would shape his musical career – John Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, George Martin – and a host of others are on the fringe, waiting to splinter it into new, uncharted directions.

Before the psychedelic period took hold, McCartney was getting used to experimenting outside of the Beatles unit. With John Lennon he’d produced The Silkie (‘You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away’), moving on to produce Cliff Bennett & The Rebel Rousers’ ‘Got to Get You into My Life’ on his own. Chapter 7 takes up the thread of these Beatles side-projects with the songs McCartney wrote for Peter & Gordon. But it’s important to note that his first major non-Beatles album, released long before the band broke up, was not in the pop mainstream at all. It provided instead the opening chords to McCartney’s classical career, later to flourish in the 1990s.

In 1966, McCartney decided to try his hand at a film soundtrack. It was the idea of writing for a new medium that came first, rather than inspiration from a particular film. “I rang our Nems office and said I would like to write a film theme,” he told the press at the time, “not a score, just a theme. John was away filming so I had time to do it. Nems fixed it for me to do the theme of The Family Way.”

Starring Hayley Mills, The Family Way was based on a play by Bill Naughton. It gave McCartney a taste of writing outside of The Beatles and for an orchestra. He worked closely with George Martin, who literally had to force him to write the main love theme. “I went to America for a time and on returning realised we needed a love theme for the centre of the picture, something wistful,” he reported. “I told Paul and he said he’d compose something. I waited but nothing materialised, and finally I had to go round to Paul’s house and literally stand there till he’d composed something.” Despite the pressure, the finished result won an Ivor Novello award for Best Instrumental Theme. “John was visiting and advised a bit,” said Martin, who himself listened and wrote down what he heard as manuscript. So this first major solo work for McCartney was, as with any solo music, actually channelled and influenced directly by others. As the albums covered in Chapters Five and Eight show, solo music probably only becomes truly so when it’s ‘isolationist’.

From Hayley Mills’ swinging London, fast forward to Bridgewater Hall in Manchester on a Sunday night in 1997. Andrew Poppy is presenting a paper on ‘The Presence of Performance in the Age of Electronic Transmission’. He is an avant-garde composer whose work is performed at events like Experiments & Eccentricities, in which piano and violin interpret works with names like ‘Romance in C for Optional Lovers’ together with pieces by Cornelius Cardew, the renowned lateral thinker of composition.

Poppy’s presentation is part of Cosmopolis, a symposium “exploring the cultural and social transition from post industrial to digital city.” The Beatles may seem a million miles away from this musical event but there Poppy puts his finger on the precise moment when The Beatles changed from being a rock and roll combo into a meeting of experimental minds. “The Beatles exploited the early multitrack tape recorder in a particular way,” he said. “They were aware of avant-garde composers John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, and they collaged random bits of radio broadcast with George Martin string arrangements and their own rock and roll.” Stockhausen and Cage worked in the live environment but The Beatles had their own – the vinyl environment – and the results they were beginning to come up with were the first true record productions: “a musical experience that could not happen outside the frame of the loudspeakers,” as Poppy described it. “The space it presents is a shameless construction.”

The Beatles weren’t the first musicians to tackle the avant-garde concepts explored in this book. As the psychedelic era dawned, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison drew on composers dating back decades, centuries even, as well as those around them in the present day. But they were among the first to take these concepts, and new experiments in sound, and press them on vinyl for a mass audience. The composers Poppy mentions – Stockhausen and Cage – were established avant-garde, fringe artists by the mid-1960s. But by their very nature, when The Beatles pressed their own interpretations onto vinyl, they went straight onto several million turntables.

When the band gave up touring they built a massive new concert venue, with Abbey Road on the stage and every teenager’s bedroom speakers in the auditorium. “If I sit and play the piano in your presence – is that performance?” asks Andrew Poppy. “If I push the fader up at some point while mixing a recording of the piano playing – is that performance? If I package the recording and send it out into the world – is that performance? A CD is a product of mechanical reproduction. Recordings atomise and fragment musical performance so as to transform its sound materials into a storable form. The sound of a pianist playing is to all intents and purposes retrieved and projected in the space that exists between two speakers.”

As one of the 20th century’s most important avant-garde composers, Karlheinz Stockhausen has over 60 years of performance and composition behind him. His selected back catalogue was re-released in 2002, spanning 62 CDs. But as a consequence of the unique sound stage The Beatles had built, as described by Poppy, this is eclipsed by a single Beatles track. The White Album’s ‘Revolution 9’, John Lennon’s epic and disturbing sound collage, is perhaps the world’s most well-known and most listened-to piece of avant-garde music.

Paul McCartney Goes Too Far was an album title bandied around in that Wimpole Street attic in the mid-60s. McCartney wanted to take the array of left-field musical ideas he was beginning to encounter and put out an album that would really surprise people. But he was only on the cusp of an ocean of sounds and influences outside of The Beatles and rock and roll. He probably wasn’t aware of just how far ‘Too Far’ could actually be.

2

INFLUENCES, MEMORIES AND BEATLES

When the final sensational piano chord crashed in at the end of The Beatles’ ‘A Day in the Life’, the closing song on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, pop music came of age in an instant and the psychedelic era had an audible point focus. But that final chord wasn’t quite the end of the album. Forty-five seconds of pure ambient sound followed, as the microphones recorded the piano notes slowly mixing into silence. A joyful avant-garde sound collage then burst forth on copies of the LP played on turntables that didn’t have ‘modern’ automatic arms. These unexpected reverberations, an avant-garde PS at the end of one of pop music’s most captivating ‘letters’, lit the blue touch paper for experimentalist pop music.

Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran... The influences behind The Beatles’ formation and their early songs are well known. Less so the avant-garde and experimental artists that steered them into such new, uncharted waters.

The German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen and the American composer John Cage certainly cast an enormous shadow, and their influence on McCartney, and modern music in general, is huge. But they were only a part of the picture. Stockhausen and Cage were the kind of avant-garde composers McCartney learned about in conversation but didn’t get to actually hear or see particularly much. Those he did played just as great a part in broadening his field of (aural) vision.

As such, George Martin’s influence is immeasurable. Not only for the famous classical influence but also for Martin’s off-the-wall electronic experiments (under the pseudonym of Ray Cathode), which are much less well known. Max Mathews, Cornelius Cardew and Luciano Berio were other cutting-edge experimental composers McCartney saw and heard from a distance, their influence balanced by those he actually met and talked to, like Daevid Allen and Delia Derbyshire.

All these influences and more had an impact on McCartney in the mid-1960s and have slowly but surely poured out across the following 40 years in the form of his own experimental music. The early results – McCartney and The Beatles’ avant-garde experiments – have been subject to intense scrutiny since the moment they were pressed onto vinyl. ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ (featuring McCartney’s tape-loop symphony), ‘Revolution 9’ (Lennon’s reply) and the freeform orchestral brilliance in ‘A Day in the Life’ are the main songs in question.

When put together, these songs act as another major influence on McCartney’s later experimental work. There is little point in detailing the exact elements provided by each Beatle in these tracks. As McCartney himself said, “We were four corners of the same square.” It was the combined effect of the four players and these recordings that sent shock waves though pop music and made an explosive start to McCartney’s musical experiments.

While volumes have been written about ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘Revolution 9’ and ‘A Day in the Life’, there has been less investigation of The Beatles’ other important – and equally freaky – pieces, namely ‘Pantomime (Everywhere It’s Christmas)’, ‘Carnival of Light’ and ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Inner Groove’. The latter is the tiny burst of tape collage that extended Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band into an album of infinite length.

‘Carnival of Light’ was The Beatles’ great sound-collage experiment which – although still unreleased – gets a chapter to itself in this book. While all The Beatles’ avant-garde work was created for record rather than live performance, ‘Carnival of Light’ was the exception because it was created for a ‘happening’. Tape collage, of course, has become the norm nowadays, ‘happenings’ having sowed the seeds of the club culture which today provides the framework in which such collages are played.

As soon as The Beatles signed with his Parlophone division of EMI Records on 9 May 1962, George Martin became a fundamental part of the band’s sound and a key influence in their musical development. It was Martin who suggested a bluesy harmonica part for the band’s first single, ‘Love Me Do’. Later on, he would open their ears to classical music, his influence memorably inspiring the strings on ‘Yesterday’ and the orchestral interludes in ‘For No One’. At an early age, George Martin had been blown away by the work of Debussy, especially ‘L’Aprés midi d’un faune’. Exposure to both Debussy and Erik Satie – late-19th century composers with a visionary spirit and total disregard for convention – would play a major part in shaping the young McCartney’s interests outside rock and roll.

Unlike most other record producers at the time, George Martin was only too ready to work with The Beatles’ wackier ideas. He had built up quite some skill in tape looping and editing from producing breakneck comedy records for the likes of Peter Sellers and The Goons. These were almost cinematic radio plays made from dialogue, special effects and breakneck editing of Sellers’ sketches like ‘Shadows in the Grass’. Martin had a thirst for electronic music too. Inspired by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, which was located not far from Abbey Road, he cut a bizarre electronic dance single and released it in 1962 under the guise of Ray Cathode.

“Creating atmosphere and sound pictures, that was my bag,” remembered Martin. “I did a lot of it before The Beatles even came along.” ‘Time Beat’ and its B-side ‘Waltz in Orbit’ by Ray Cathode mixed live musicians over a purely synthesised electronic rhythm track Martin had created with the Radiophonic Workshop. “It was a resounding flop,” he later remembered, “but an interesting flop ... Something to learn from anyway!”

One of the leading lights of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was Delia Derbyshire. Martin described their lab and her colleagues as “people who spent their entire time cooking up freaky sounds with whatever they could lay their hands on. They had, to them, standard equipment of oscillators and variable-speed tape machines, but they also indulged in quite a bit of concrete music [using] milk bottles, bits of old piping...”

Delia Derbyshire was 25 when Ray Cathode’s ‘Time Beat’ was released as a single. At the time she was assisting the experimental composer Luciano Berio (who would later cross paths with Paul McCartney) at his Dartington summer school lectures. Having earned a degree in mathematics in Cambridge she was turned down – or rather, refused to allow to apply – for a job at Decca Records. In the late 1950s and early ’60s they simply did not employ women in their recording studios.

Instead she went to work for the BBC as a trainee studio manager and quickly moved sideways into the fledgling Radiophonic Workshop, a hi-tech studio set up to push the boundaries of sound and soundtracks. She became their lynch-pin, enthusiastically exploring sound creation (and perception) using the Workshop’s vast banks of technology. Modes, moods, tuning and transfer of electronic music all came under Derbyshire’s intense research. A lot of it was based around her mathematical training, even if she’d cheerfully break or bend any scientific rule to find a new, emotive sonic experience.

The Radiophonic Workshop and Delia Derbyshire had a job to do too, however. It had been set up to service the BBC’s Radio Drama department, effectively as a sound effects lab and editing suite. But the team there could not quell their avant-garde spirit and pushed the available technology into new music, the most famous being the theme music for Doctor Who. This famous theme ‘song’ led to a slew of TV commissions for Derbyshire and her team, who between them made orchestras virtually redundant for a time. ‘Special sound by BBC Radiophonic Workshop’ was how the TV credits ran, with individual staff gaining no recognition at all. Derbyshire’s impact is only now being reassessed, with the Guardian calling her “the unsung heroine of British electronic music” when she died in 2001, having spent much of the 1980s and ’90s away from music, thoroughly disillusioned.

Following on from her work with Berio, Derbyshire worked with other composers, including Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Roberto Gerhard (on ‘Anger of Achilles’, which won the 1965 Prix Italia) and Ianni Christou. But the BBC was unable to fit her avant-garde work into their mainstream programming, calling it “too lascivious for 11-year-olds [and] too sophisticated for the BBC2 audience.” So she invested her time in Unit Delta Plus, Kaleidophon and Electrophon, three private studios where she pioneered electronic music as we know it today. Another outlet for Derbyshire’s work was the emerging psychedelic scene. She provided music for Yoko Ono’s pre-Lennon Wrapping Event and got involved in happenings and raves, like those at the Roundhouse in Camden, explored in more detail in the next chapter.

Paul McCartney was inspired by what he’d heard of the BBC’s experimental sound installation, and by the work George Martin had done with them. In a moment that could have altered the course of pop history, he seriously considered abandoning the string quartet recorded for ‘Yesterday’ in favour of a purely electronic backing. In 1998, McCartney recounted how he pulled the Workshop’s phone number out of the directory and went there to introduce himself and find out more. He hit it off with Derbyshire immediately and was totally into the experimental work she was producing, most likely because it was reminiscent of his in two key ways – pushing the boundaries while remaining highly melodic and emotional.

But the meeting McCartney remembered (as recounted in his authorised biography Many Years from Now) was slightly blurred by the passage of time. It wasn’t the Radiophonic Workshop he visited, but the private lab of Derbyshire’s friend and colleague Peter Zinovieff, which both used when their experiments became too much for the BBC. Just before she died in 2001, Derbyshire described her meeting with McCartney in an interview with John Cavanagh for Boazine.

■ He never came to the workshop. I always did work outside and he came to [Peter] Zinovieff’s studio and I played him some of my stuff – that’s all ... It was the phrase length he was interested in. I’ve always been non-conformist: I don’t like the 8-bar or the 12-bar standard thing. They’re all beautiful in their own way, but why not explore different phrase lengths? [McCartney] never came to the workshop ... Brian Jones did – golly! There we were with our hand-tuned oscillators and he went into it with his frilly cuffs and things as though he could play it as a musical instrument! He died very young and I cried buckets.

Before going to meet Delia Derbyshire – wherever it was – McCartney had had his mind blown by an album from another unsung pioneer of electronic music. George Martin had played him a recording by Max V Mathews, which had been a major inspiration for his own Ray Cathode alter ego.

Decca Records may have turned Delia Derbyshire away but in 1962 they did release a far-out album, entitled Music from Mathematics. It was one of the most influential and important albums in the history of electronic music and featured 18 different ‘songs’ generated by an IBM 7090 computer and a digital to sound transducer. Mathews was one of seven programmers whose work on the 7090 appeared on the final album, his contributions being electronic interpretations of ‘Bicycle Built for Two’, ‘Numerology’, ‘The Second Law’, ‘May Carol’ and ‘Joy to the World’. Mathews, known as the “father of electronic music” and “the grandfather of techno”, had not only programmed a computer to play music but also to simulate vocals. “The computer can also be programmed to speak and sing, as is illustrated by the last verse of this familiar ditty,” he wrote of ‘Bicycle Built for Two’. “The patterns of human speech are analysed in the same manner as the instrumental sounds. The computer is then programmed to speak the desired words. On this [track] the computer not only was programmed to sing but also to simulate a Honky Tonky type of piano accompaniment that was popular during the era when this song was a hit.”

Max V Mathews was 32 when Music from Mathematics was released. He had first shown the potential of digital music five years earlier with his 1957 Music I computer program and was a leading figure in acoustic research at AT&T Bell Laboratories, where he worked from 1955 until 1987. In the late 1970s, he also acted as Scientific Adviser to the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM) in Paris, whose groundbreaking ideas set the scene for the most non-technical of avant-garde music-making in Chapter 6. His other notable inventions include the Music and Groove software series and the Radio Baton, a computer-linked baton for ‘conducting’ electronic symphonies.

Music from Mathematics is a ‘Eureka! moment’ album. With the IBM 7090 Mathews had created a new kind of musical instrument and a whole new genre of music was about to emerge as a result. “This new ‘instrument’ combination is not merely a gadget or a complicated bit of machinery capable of producing new sounds,” he declared in the album’s liner notes. “It opens the door to the exploration and discovery of many new and unique sounds. However, its musical usefulness and validity go far beyond this. With the development of this equipment carried out at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, the composer will have the benefits of a notational system so precise that future generations will know exactly how the composer intended his music to sound. He will have at his command an ‘instrument’ which is itself directly involved in the creative process.” In an essay that stands as a fitting preface to the history of electronic music in general, Mathews concluded:

■ The human element plays a large role in computer music, as in any art medium. The sounds and sound-producing methods are new; the composer’s role is essentially that which it has always been. History tells us that whenever a new concept emerges, it is labelled revolutionary by either its proponents or the public at large. The new techniques and tools of computer music are not meant to replace the more traditional means of composition and performance. Rather, they are designed to enhance and enlarge the range of possibilities available to the searching imagination of musicians. Science has provided the composer with new means to serve the same ends – artistic excellence and communication.

On hearing Music from Mathematics in the summer of 1963, composer Ivor Darreg was amazed by the “bass voice with good dynamic range and only the slightest ‘electrical accent’” that Mathews had achieved with his computers. “It is important to realise that this was accomplished on machines never intended for musical purposes,” Darreg wrote at the time, “but merely for prosaic, non-artistic tasks like adding up the weekly payroll or doing the mathematical drudgery for a roomful of engineers.” He was convinced that “the ‘psychological moment’ for electronic music has arrived.”

Paul McCartney, too, was taken aback when George Martin played him this landmark recording, and he continued to listen to it outside the studio – his friend and counter-culture mover Barry Miles had a copy and the two would often play it at Miles’ flat. McCartney remains enthused by electronic music to the present day. The light bulbs that Music from Mathematics turned on can be heard predominantly on his McCartney II album from 1980, the first Fireman album, Strawberries Oceans Ships Forest, from 1993, and even his Mellow Extension mix of ‘Vo!ce’ from 2001.

Of course, in the 1960s, just as John Lennon was the most famous Beatle into tape loops, George Harrison was the band’s most visible proponent of this new wave of music. Although he followed a much more traditional path for the rest of his solo career, Harrison’s Electronic Sound album from 1969 put the possibilities of the Moog synthesiser in front of a huge new audience.

Max V Mathews had inspired the work of Delia Derbyshire and George ‘Ray Cathode’ Martin in England. In the US one of his main disciples was Morton Subotnick, whose debut album, Silver Apples of the Moon, made it onto the turntables of Paul McCartney and almost every other fan of experimental/freaky music in 1967. Subotnick, then aged 34, had released 30 minutes of electronic sounds from his homemade array of effects gates and early synthesisers. Side two of this album is one of the first hints of techno and modern electronic music, pre-empting the sounds of Kraftwerk by nearly a decade. Subotnick later coined the term Elevator Music with his 1970s installation in a New York elevator system, which triggered pieces of music when passengers selected particular floors.

* * *

Karlheinz Stockhausen made Brian Epstein nervous. In 1967 The Beatles’ manager needed the composer’s approval for Peter Blake to use his image in the Sgt. Pepper album’s famous front-cover collage. But Stockhausen was touring and was difficult to pin down. He almost didn’t make it onto the cover, but an urgent telegram from Epstein saved the day.

■ FURTHER TO LETTER AND ENCLOSED RELEASE FORM CONCERNING BEATLES LP YOUR DECISION IS MOST URGENTLY REQUESTED ONE WAY OR ANOTHER BY RETURN STOP SORRY TO PUSH YOU BUT AT THIS STAGE SPEED IS OF THE UTMOST IMPORTANCE REGARDS AND BEST WISHES BRIAN EPSTEIN

Brian Epstein went to such lengths because Stockhausen was so important to The Beatles – to McCartney and Lennon especially. McCartney had been hearing about Stockhausen’s work since his teens and began to explore it and actually listen to it in more detail when the psychedelic period arrived. He later described the composer’s seamless mix of primitive electronic sound and human vocals, ‘Song of the Youths’, as his favourite “plick plop” piece.

‘Song of the Youths’ (‘Gesang der Jünglinge’) started life as an electronic mass for Cologne cathedral. Stockhausen thought on a panoramic scale and wanted this grand venue to put electronic music in front of as many people as possible. But Cologne cathedral had other ideas and instead a truncated version of ‘Song of the Youths’ (originally titled ‘The Song of the Youths in the Fiery Furnace’) was performed via five speaker panels in a broadcasting studio of West German Radio in May 1956. The venue may have changed but the impact wasn’t lessened. Stockhausen’s 13-minute mix of sine wave, speech and white noise became the talk of the avant-garde and put the new electronic genre firmly on the map.

Born in 1928, Stockhausen had already composed several groundbreaking works as a student in Cologne and Paris before creating ‘Gesang der Jünglinge’. There was a passion and intensity to this and his other 1950s works that transfixed a generation of European composers, influencing both Boulez and Berio.

Following a spell in the USA, where he met John Cage, Stockhausen worked with Cornelius Cardew to produce minimalist orchestral pieces that were both more fluid and more relaxed than his previous work. From the mid-1960s until the end of the decade the composer progressed to concentrate almost solely on music made with tape cut-ups and electronics. He poured and mixed sound as if it was some physical, malleable paint in pieces such as ‘Mikrophonie I’ (1964), ‘Prozession’ (1967), ‘Kurzwellen’ (1968) and ‘Aus den sieben Tagen’ (1968). All four were being toured around Europe when Epstein started trying to track Stockhausen down.

Outside the live situation and back in his studio, Stockhausen created the seminal early tape compositions ‘Telemusik’ (1966) and ‘Hymnen’ (1967). The latter, which pulled together recordings and samples from around the globe, was heard and loved by John Lennon and was a major influence on ‘Revolution 9’.

In the 1970s, Stockhausen mixed simpler, classical compositions with full-blown performance art. ‘Trans’ (1971) was written for an orchestra bathed in violet light, only to be observed through a veil. ‘Sirius’ (1977) was a scored ceremony for four peculiarly costumed musicians and synthesised and processed audio tape. All were clearly major influences on McCartney’s later live performances explored in Chapter 14.

Alongside Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage is the composer most often cited as The Beatles’ and McCartney’s prime influence in avant-garde music. Born in 1912 in Los Angeles, Cage casts an enormous shadow over the past 50 years of both avant-garde and electronic/dance music. Nineteenth century piano melodies and the dawn of modern radio invigorated his childhood and provided the foundation for his life’s work. His late teens saw him studying for the priesthood before travelling around Europe. Visiting Berlin and Paris, he developed a passion for writing poetry and composing music. At 21 he began studying under Henry Cowell at California’s New School for Social Research. There he absorbed all sorts of experimental ideas and an unconventional approach to music making. These were both logistical, such as methods of retuning the piano and use of the electronic Therminvox device, and influential – he was exposed to Eastern music and the visionary ideas of his teacher Arnold Schoenberg.

Schoenberg and Cage impressed each other equally with their disregard for traditional musical understanding and constant questioning and reinvention of what music actually is and could be. In a groundbreaking 1937 lecture, The Future of Music (Credo), Cage identified two of the major directions that modern music would take. Firstly, he predicted how electronic sound and devices would become the crux of composition. Electronics, he said, would mean that “no rhythm would be beyond the composer’s earth.” He tried to put this theory into practice as part of a quartet, the Magnetic Tape Music Project. Cage also predicted the rise of music created by playing re-engineered machines rather than instruments.

Between 1939 and 1952 Cage started putting both these concepts into practice with the five-part ‘Imaginary Landscapes’ series. Prefiguring DJ culture by almost 50 years, ‘Imaginary Landscapes No. 1’ was the sound of vari-speed turntables playing RCA test discs. ‘Imaginary Landscapes No. 4’ was the sound of overlapping radios being tuned and re-tuned. In the final piece in the series, Cage pre-empted 1980s and 1990s sampling and collage music by creating a new aural landscape by mixing 42 jazz records at once. He would later revisit this merging of previously recorded music into a new, recycled performance with the revolutionary ‘Williams Mix’, a composition based on the random playback of 600 albums.

Cage’s radios-as-music concept in ‘Imaginary Landscapes No. 4’ was just one piece that sent ripples across the surface of avant-garde music, continuing to do so to this day. McCartney later tried out radio-play for himself on ‘The Broadcast’ in 1979 and ‘Trans Lunar Rising’ in 1993. John Lennon was equally inspired and pulled a radio into the mix for ‘I Am the Walrus’. Randomly tuning through the stations, he found a BBC broadcast of the Shakespeare play King Lear, which is now immortalised in the finished Magical Mystery Tour recording.

The ‘Imaginary Landscapes’ sowed the seeds of modern-day dance and experimental music, but attention is more often drawn to another piece of Cage’s revolutionary thinking from 1952. This was the year he first performed ‘4’33”’, an avant-garde composition which took music to its most challenging conclusion, when he sat at the piano for four and a half minutes of nothingness. ‘4’33”’ was not a performance of complete silence, as is the generally received notion. Instead it made the statement that music could be the random, ambient sound around an audience during a predetermined time-span.

Integrating music with random, everyday elements became a theme of Cage’s work across the 1940s and early 50s. He invented the ‘prepared piano’, writing for pianos whose strings had been entwined with various small, everyday objects to create a new percussive sound. His ‘Living Room Music’ pieces devolved percussion further into the hands of the listener and the objects that surround them. In the late 1940s Cage composed some of his most important works, inspired by two new influences. An interest in Zen Buddhism and a love of composer Erik Satie pushed him in minimalist, ambient directions. At the same time, an interest in the I Ching and a friendship with surrealist artist Marcel Duchamp created in him a desire to base composition on randomness and chance. 1951’s ‘Music of Changes’ embraced all these concepts, its ethereal piano passages being joined in a structure based on random coin-tossing.

The roots of DJ culture and interactive music can be traced back to John Cage. As can the roots of multimedia art with the primitive, computer-generated elements in 1968’s ‘HPSCHD’, which duetted traditional instruments (harps) with machines and media (tapes and cartridges). In the late 1950s Cage was back in Europe working with Luciano Berio and recording electronic feedback and hiss to create the sprawling ‘Fontana Mix’.

Despite clearly working to his own futurist agenda, John Cage was not afraid to collaborate or comment on others’ work. He had a love-hate relationship with his closest European peer, Karlheinz Stockhausen. ‘Variations’ was an attempt to further random composition into true ‘indeterminacy’, where sounds would be triggered by devices and the movement of dancers, and was a reaction to Stockhausen’s ‘Klavierstuck’ series.

In 1937 Cage gave a lecture in Seattle where he summed up the thinking behind his unique music. “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating. The sound of a truck at 50 mph. Static between the stations. Rain. We want to capture and control these sounds, to use them, not as sound effects, but as musical instruments.” Outlining his vision for the future of avant-garde music, he went on to set the scene for sampling, remixing and DJ culture when he explained:

■ Every film studio has a library of ‘sound effects’ recorded on film. With a film phonograph it is now possible to control the amplitude and frequency of any one of these sounds and to give to it rhythms within or beyond the reach of anyone’s imagination. Given four film phonographs, we can compose and perform a quartet for explosive motor, wind, heartbeat, and landslide.

Paul McCartney saw these theories put into practice and heard avant-garde music ‘live’ for the first time when he went with Barry Miles to a lecture by Delia Derbyshire’s former mentor, Luciano Berio. Both had enjoyed ‘Thema (Omaggio a Joyce)’, Berio’s pioneering electronic soundscape from 1958 which cut up, looped and ‘remixed’ a reading of Ulysses in homage to its author, James Joyce. Berio had followed this with ‘Allez-Hop’ (1959), which did the same with a text by Calvino.

Italy’s most important avant-garde explorer, Berio was 41 when he came to London to lecture at the Italian Cultural Institute. He had studied as a child with the Milan Conservatoire and then moved into more experimental circles, setting up a laboratory for electronic music in 1955 with fellow experimentalist Bruno Maderna. He would later head the aforementioned institution of academic research into electronic music, ICRAM, in Paris and Milan. Berio spent the 1960s lecturing all over Europe and America, stopping off at Darmstadt, Harvard, the Juilliard School in New York and Columbia University.

During this time, Luciano Berio brought many new influences, such as folk and rock, into his work while extending his passion for the human voice. His muse was his wife, Cathy Berberian, who would perform much of his work – most notably ‘Folk Songs’ (1964). Berio was also inspired by jazz, the Japanese art of Noh and Indian music.