1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

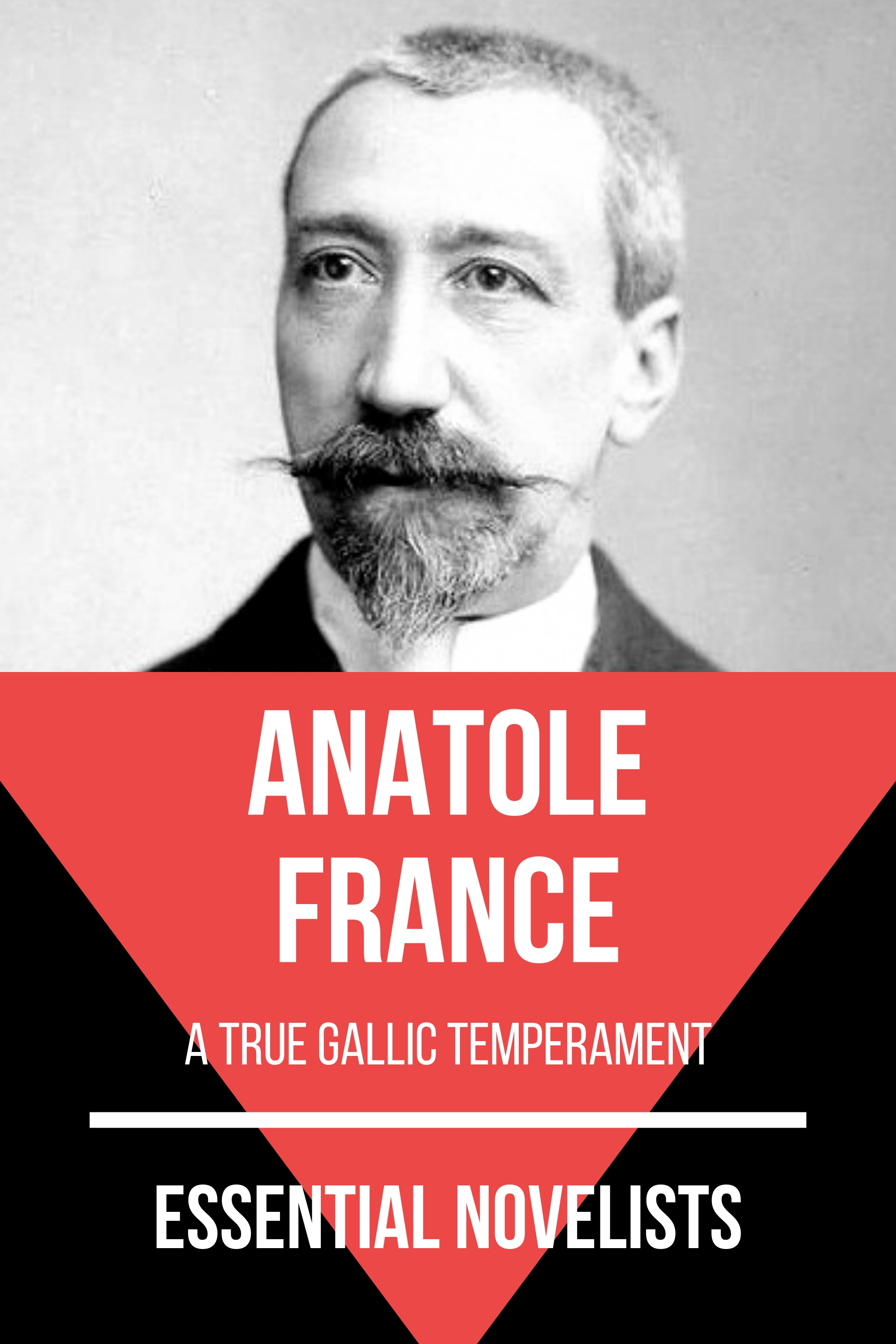

- Herausgeber: Anatole France

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A FEW Frenchmen, united in friendship, who were spending the spring in Rome, were wont to meet amid the ruins of the disinterred Forum. They were Joséphin Leclerc, an Embassy Attaché on leave; M. Goubin, licencié ès lettres, an annotator; Nicole Langelier, of the old Parisian family of the Langeliers, printers and classical scholars; Jean Boilly, a civil engineer, and Hippolyte Dufresne, a man of leisure, and a lover of the fine arts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The White Stone

By

Anatole France

(Philopatris, xxi.)

And to me it seems that you have fallen asleep upon a white rock, and in a parish of dreams, and have dreamt all this in a moment while it was night.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER_I

CHAPTER_II

CHAPTER_III

CHAPTER_IV

CHAPTER_V

CHAPTER_VI

CHAPTER I

A FEW Frenchmen, united in friendship, who were spending the spring in Rome, were wont to meet amid the ruins of the disinterred Forum. They were Joséphin Leclerc, an Embassy Attaché on leave; M. Goubin, licencié ès lettres, an annotator; Nicole Langelier, of the old Parisian family of the Langeliers, printers and classical scholars; Jean Boilly, a civil engineer, and Hippolyte Dufresne, a man of leisure, and a lover of the fine arts.

Towards five o’clock of the afternoon of the first day of May, they wended their way, as was their custom, through the northern door, closed to the public, where Commendatore Boni, who superintended the excavations, welcomed them with quiet amenity, and led them to the threshold of his house of wood nestling in the shadow of laurel bushes, privet hedges and cytisus, and rising above the vast trench, dug down to the depth of the ancient Forum, in the cattle market of pontifical Rome.

Here, they pause awhile, and look about them.

Facing them rise the truncated shafts of the Columnæ Honorariæ, and where stood the Basilica of Julia, the eye rested on what bore the semblance of a huge draughts-board and its draughts. Further south, the three columns of the Temple of the Dioscuri cleave the azure of the skies with their blue-tinted volutes. On their right, surmounting the dilapidated Arch of Septimus Severus, the tall columns of the Temple of Saturn, the dwellings of Christian Rome, and the Women’s Hospital display in tiers, their facings yellower and muddier than the waters of the Tiber. To their left stands the Palatine flanked by huge red arches and crowned with evergreen oaks. At their feet, from hill to hill, among the flagstones of the Via Sacra, narrow as a village street, spring from the earth an agglomeration of brick walls and marble foundations, the remains of buildings which dotted the Forum in the days of Rome’s strength. Trefoil, oats, and the grasses of the field which the wind has sown on their lowered tops, have covered them with a rustic roof illumined by the crimson poppies. A mass of débris, of crumbling entablatures, a multitude of pillars and altars, an entanglement of steps and enclosing walls: all this indeed not stunted but of a serried vastness and within limits.

Nicole Langelier was doubtless reviewing in his mind the host of monuments confined in this famed space:

“These edifices of wise proportions and moderate dimensions,” he remarked, “were separated from one another by narrow streets full of shade. Here ran the vicolibeloved in countries where the sun shines, while the generous descendants of Remus, on their return from hearing public speakers, found, along the walls of the temples, cool yet foul-smelling corners, whence the rinds of water-melons and castaway shells were never swept away, and where they could eat and enjoy their siesta. The shops skirting the square must certainly have emitted the pungent odour of onions, wine, fried meats, and cheese. The butchers’ stalls were laden with meats, to the delectation of the hardy citizens, and it was from one of those butchers that Virginius snatched the knife with which he killed his daughter. There also were doubtless jewellers and vendors of little domestic tutelary deities, protectors of the hearth, the ox-stall, and the garden. The citizens’ necessaries of life were all centred in this spot. The market and the shops, the basilicas, i.e., the commercial Exchanges and the civil tribunals; the Curia, that municipal council which became the administrative power of the universe; the prisons, whose vaults emitted their much dreaded and fetid effluvia, and the temples, the altars, of the highest necessity to the Italians who have ever some thing to beg of the celestial powers.

“Here it was, lastly, that during a long roll of centuries were accomplished the vulgar or strange deeds, almost ever flat and dull, oftentimes odious and ridiculous, at times generous, the agglomeration of which constitutes the august life of a people.”

“What is it that one sees, in the centre of the square, fronting the commemorative pedestals?” inquired M. Goubin, who, primed with an eye-glass, had noticed a new feature in the ancient Forum, and was thirsting for information concerning it.

Joséphin Leclerc obligingly answered him that they were the foundations of the recently unearthed colossal statue of Domitian.

Thereupon he pointed out, one after the other, the monuments laid bare by Giacomo Boni in the course of his five years’ fruitful excavations: the fountain and the well of Juturna, under the Palatine Hill; the altar erected on the site of Cæsar’s funeral pile, the base of which spread itself at their feet, opposite the Rostra; the archaic stele and the legendary tomb of Romulus over which lies the black marble slab of the Comitium; and again, the Lacus Curtius.

The sun, which had set behind the Capitol, was striking with its last shafts the triumphal arch of Titus on the towering Velia. The heavens, where to the West the pearl-white moon floated, remained as blue as at midday. An even, peaceful, and clear shadow spread itself over the silent Forum. The bronzed navvies were delving this field of stones, while, pursuing the work of the ancient Kings, their comrades turned the crank of a well, for the purpose of drawing the water which still forms the bed where slumbered, in the days of pious Numa, the reed-fringed Velabrum.

They were performing their task methodically and with vigilance. Hippolyte Dufresne, who had for several months been a witness of their assiduous labour, of their intelligence and of their prompt obedience to orders, inquired of the director of the excavations how it was that he obtained such yeoman’s work from his labourers.

“By leading their life,” replied Giacomo Boni. “Together with them do I turn over the soil; I impart to them what we are together seeking for, and I impress on their minds the beauty of our common work. They feel an interest in an enterprise the grandeur of which they apprehend but vaguely. I have seen their faces pale with enthusiasm when unearthing the tomb of Romulus. I am their everyday comrade, and if one of them falls ill, I take a seat at his bedside. I place as great faith in them asthey do in me. And so it is that I boast of faithful workmen.”

“Boni, my dear Boni,” exclaimed Joséphin Leclerc, “you know full well that I admire your labours, and that your grand discoveries fill me with emotion, and yet, allow me to say so, I regret the days when flocks grazed over the entombed Forum. A white ox, from whose massive head branched horns widely apart, chewed the cud in the unploughed field; a hind dozed at the foot of a tall column which sprang from the sward, and one mused: Here was debated the fate of the world. The Forum has been lost to poets and lovers from the day that it ceased to be the Campo Formio.”

Jean Boilly dwelt on the value of these excavations, so methodically carried out, as a contribution towards a knowledge of the past. Then, the conversation having drifted towards the philosophy of the history of Rome:

“The Latins,” he remarked, “displayed reason even in the matter of their religion. Their gods were commonplace and vulgar, but full of common sense and occasionally generous. If a comparison be drawn between this Roman Pantheon composed of soldiers, magistrates, virgins, and matrons and the deviltries painted on the walls of Etruscan tombs, reason and madness will be found in juxtaposition. The infernal scenes depicted in the mortuary chambers of Corneto represent the monstrous creations of ignorance and fear. They seem to us as grotesque as Orcagna’s Day of Judgment in Santa Maria Novella at Florence, and the Dantesque Hell of the Campo Santo of Pisa, whereas the Latin Pantheon reflects for ever the image of a well-organised society. The gods of the Romans were like themselves, industrious and good citizens. They were useful deities, each one having its proper function. The very nymphs held civil and political offices.

Look at Juturna, whose altar at the foot of the Palatine we have so frequently contemplated. She did not seem fated by her birth, her adventures, and her misfortunes to occupy a permanent post in the city of Romulus. An incensed Rutula, beloved by Jupiter, who rewarded her with immortality, when King Turnus fell by the hand of Æneas, as decreed by the Fates, she flung herself into the Tiber, to escape thus from the light of day, since it was denied her to perish with her royal brother. Long did the shepherds of Latium tell the story of the living nymph’s lamentations from the depths of the river. In later years, the villagers of rural Rome, when looking down at night-time over the bank, imagined that they could see her by the moon’s rays, lurking in her glaucous garments among the rushes. The Romans, however, did not leave her to the idle contemplation of her sorrows. They promptly conceived the idea of allotting to her an important duty, and entrusted her with the custody of their fountains, converting her into a municipal goddess. And so it is with all their divinities. The Dioscuri, whose temple lives in its beautiful ruins, the Dioscuri, the brothers of Helen, the sparkling Gemini, were put to good use by the Romans, as messengers of the State. The Dioscuri it was, who, mounted on a white charger, brought to Rome the news of the victory of Lake Regillus.

The Italians asked of their gods only temporal and substantial benefits. In this respect, notwithstanding the Asiatic fears which have invaded Europe, their religious sentiment has not changed. That which they formally demanded from their gods and their genii, they nowadays expect from the Madonna and the Saints. Every parish possesses its Beatified patron, to whom requests are preferred just as in the case of a Deputy. There are Saints for the vine, for cereals, for cattle, for the colic, and for toothache. Latin imagination has repeopled Heaven with a multitude of living bodies, and has converted Judaic monotheism into a new polytheism. It has enlivened the Gospels with a copious mythology; it has re-established a familiar intercourse between the divine and the terrestrial worlds. The peasantry demand miracles of their protecting Saints, and hurl invectives at them if the miracle is slow of manifestation. The peasant who has in vain solicited a favour of the Bambino, returns to the chapel, and addressing on this occasion the Incoronata herself, exclaims:

“I am not speaking to you, you whoreson, but to your sainted mother.”

“The women make the Madre di Dio a confidant of their love affairs. They believe with some show of reason that being a woman she understands, and that there is no need to be on a footing of delicacy with her. They have no fear of going too far—a proof of their piety. Hence we must view with admiration the prayer which a fine lass of the Genoese Riviera addressed to the Madonna: ‘Holy Mother of God, who didst conceive without sin, grant me the grace of sinning without conceiving.’”

Nicole Langelier here remarked that the religion of the Romans lent itself to the evolution of Rome’s policy.

“Bearing the stamp of a distinctly national character,” he said, “it was, for all that, capable of penetrating the minds of foreign nations, and of winning them over by its sociable and tolerant spirit. It was an administrative religion propagating itself without effort together with the rest of the administration.”

“The Romans loved war,” said M. Goubin, who studiously avoided paradoxes.

“They loved not war for itself,” was Jean Boilly’s rejoinder. “They were far too reasonable for that. That military service was to them a hardship is revealed by certain signs. Monsieur Michel Bréal tells you that the word which primarily expressed the equipment of the soldier, ærumna, subsequently assumed the general meaning of lassitude, need, trouble, hardship, toil, pain, and distress. Those peasants were just as other peasants. They entered the ranks merely because compelled and forced thereto. Their very leaders, the wealthy proprietors, waged war neither for pleasure nor for glory. Previous to entering on a campaign, they consulted their interests twenty times over, and carefully computed the chances.”

“True,” said M. Goubin, “but their circumstances and the state of the world compelled them ever to be in arms. Thus it is that they carried civilisation to the far ends of the known world. War is above all an instrument of progress.”

“The Latins,” resumed Jean Boilly, “were agriculturists who waged agriculturists’ wars. Their ambitions were ever agricultural. They exacted of the vanquished, not money, but soil, the whole or part of the territory of the subjugated confederation, generally speaking one-third, out of friendship, as they said, and because they were moderate in their desires. The farmer came and drove his plough over the spot where the legionary had a short while ago planted his pike. The tiller of the soil confirmed the soldier’s conquests. Admirable soldiers, doubtless, well disciplined, patient, and brave, who fought and who were sometimes beaten just like any others; yet still more admirable peasants. If wonder is felt at their having conquered so many lands, still more is it to be wondered at that they should have kept them. The marvel of it is that in spite of the many battles they lost, these stubborn peasants never yielded an acre of soil, so to speak.”

While this discussion was proceeding, Giacomo Boni was gazing with a hostile eye at the tall brick house standing to the north of the Forum on top of several layers of ancient substructures.

“We are about,” he said, “to explore the Curia Julia. We shall soon, I hope, be in a position to break up the sordid building which covers its remains. It will not cost the State much to purchase it for the spade’s work. Buried under nine mètres of soil on which stands the Convent of S. Adriano lie the flagstones of Diocletian, who restored the Curia for the last time. We shall surely find among the rubbish a number of the marble tables on which the laws were engraved. It is a matter of interest to Rome, to Italy, nay to the whole world, that the last vestiges of the Roman Senate should see the light of day.”

Thereupon he invited his friends into his hut, as hospitable and rustic a one as that of Evander.

It constituted a single room wherein stood a deal table laden with black potteries and shapeless fragments giving out an earthy smell.

“Prehistorical treasures!” sighed Joséphin Leclerc. “And so, my good Giacomo Boni, not content with seeking in the Forum the monuments of the Emperors, those of the Republic, and those of the Kings, you must fain sink down into the soil which bore flora and fauna that have vanished, drive your spade into the quaternary, and the tertiary, penetrate the pliocene, the miocene, and the eocene; from Latin archæology you wander to prehistoric archæology and to palæontology. The salons are expressing alarm at the depths to which you are venturing. Countess Pasolini would like to know where you intend to stop, and you are represented in a little satirical sheet as coming out at the Antipodes, breathing the words: Adesso va bene!”

Boni seemed not to have heard.

He was examining with deep attention a clay vessel still damp and covered with ooze. His pale blue expressive eyes darkened while critically examining this humble work of man for some unrevealed trace of a mysterious past, but resumed their natural hue as the Commendatore’s mind wandered off into a reverie.

“These remains which you have before you,” he presently remarked, “these roughly hewn little wooden sarcophagi and these cinerary urns of black pottery and of house-like shape containing calcined bones were gathered under the Temple of Faustina, on the north-west side of the Forum.

“Black urns containing ashes, and skeletons resting in their coffins as if in a bed, are here to be met with side by side. The funeral rites of the Greeks and the Romans included both those of burial and of cremation. Over the whole of Europe, in prehistoric days, the two customs were simultaneously observed, in the same city and in the same tribe. Does this dual fashion of sepulture correspond with the ideals of two races? I am inclined to believe so.”

Picking up, with reverential and almost ritual gesture, an urn shaped like a dwelling and containing a small quantity of ashes, he went on:

“The men who in immemorial times gave this form to clay, believed that the soul, being attached to the bones and the ashes, had need of a dwelling, but that it did not require a very large house wherein to live the abridged life of the dead. These men were of a noble race which came from Asia. The one whose light ashes I now hold lived before the days of Evander and of the shepherd Faustulus.”

Then, making use of the phraseology of the ancients, he added:

Those were the days when King Vitulus, King Calf as we should say, held peaceful sway over this country so pregnant with glory. Monotonous pastoral times reigned over the Ausonian plain. These men were, however, neither ignorant nor boorish. Much priceless knowledge had come to them from their forefathers. Both the ship and the oar were known to them. They practised the art of subjecting oxen to the yoke and of harnessing them to the pole. They kindled at will the divine flame. They gathered salt, wrought in gold, kneaded and baked vases of clay. Probably too they began to till the soil. They do say that the Latin shepherds became agricultural labourers in the fabled days of the Calf. They cultivated millet, wheat, and spelt. They stitched skins together with needles of bone. They wove and perchance made wool false to its whiteness by dyeing it various colours. By the phases of the moon did they measure time. They gazed upon the heavens but to discover in them what was in the world below. They saw in them the greyhound who watches for Diospiter the shepherd who tends the starry flock. The prolific clouds were to them the Sun’s cattle, the cows supplying milk to the cerulean countryside. They worshipped the heavens as their Father, and the Earth as their Mother. At eventide, they heard the chariots of the gods, like themselves migratory, roll along the mountain roads with their ponderous wheels. They enjoyed the light of day and pondered with sadness over the life of the souls in the Kingdom of Shadows.

We know that these massive-headed Aryans were fair, since their gods, made to their own image, were fair. Indra had locks like ears of wheat and a beard as tawny as the tiger’s coat. The Greeks conceived the immortal gods with blue or glaucous eyes, and a head of golden hair. The goddess Roma was flava et candida:

“Were it possible to make a whole out of these calcined bony fragments, the result would be pure Aryan forms. In those massive and vigorous skulls, in those heads as square as the primary Rome which their sons were to build, you would recognise the ancestors of the patricians of the Commonwealth, the long flourishing stock which produced tribunes of the people, pontiffs, and consuls; you would be handling the magnificent mould of the robust brains which constructed religion, the family, the army, and the public laws of the most strongly organised city that ever existed.”

Gently placing the bit of pottery on the rustic table, Giacomo Boni bends over a coffin the size of a cradle, a coffin dug out of the trunk of an oak, and similar in shape to the early canoes of man. He lifts up the thin covering of bark and sap-wood forming the lid of that funeral wherry, and brings to light bones as frail as a bird’s skeleton. Of the body, there hardly remains the spinal column, and it would bear resemblance to one of the lowest of vertebrata, such as a big saurian, did not the fullness of the forehead reveal man. Coloured beads, which have become detached from a necklace, are scattered over these bones browned with age, washed by subterraneous waters, and exhumed from clayey soil.

“Look!” says Boni, “at this little boy who was not given the honours of cremation, but buried, and returned as a whole to the earth whence he sprung. He is not a son of headmen, nor a noble inheritor of the traits of a fair race. He belongs to the race indigenous to the Mediterranean, the race which became the Roman plebs, and which supplies Italy to the present day with subtile lawyers and calculating individuals. He was born in the Palatine City of the Seven Hills, in days seen dimly through the mist of heroic fables. It is a Romulean boy. In those days, the Valley of the Seven Hills was a morass, and the slopes of the Palatine were covered with reed-thatched huts only. A tiny lance was placed on the coffin to show that the child was a male. He was barely four years old when he fell asleep in death. Then his mother clothed him with a beautiful tunic clasped at the neck, around which she fastened a string of beads. The kinsmen did not begrudge him their offerings. They deposited on his tomb, in urns of black earthenware, milk, beans, and a bunch of grapes. I have collected these vessels and I have fashioned similar ones out of the same clay by the heat of a wood fire lit in the Forum at night. Previous to taking a last farewell of him, they ate and drank together a portion of their offerings; this funeral repast assuaged their sorrow. Child, thou who sleepest since the days of the god Quirinus, an Empire has passed over thy agrestic coffin, and the same stars which shone at thy birth are about to light up the skies above us. The unfathomable space which separates the hours of your life from those of our own constitutes but an imperceptible moment in the life of the Universe.”

After a moment’s silence, Nicole Langelier remarked:

It is as difficult to distinguish amid a people the races composing it as to trace in the course of a river the streams which mingle with it. What constitutes, moreover, a race? Do any human races really exist? I see white men, red men, and black men. But, they do not constitute races; they are merely varieties of the same race, of the same species, which form together fruitful unions and intermingle without ceasing. A fortiori, the man of learning knows not several yellow races or several white races. Human beings invent, however, races in pursuance of their vanity, their hatred, or their greed. In 1871, France became dismembered by virtue of the rights of the Germanic race, and yet no German race has an existence. The antiemites kindle the hatred of Christian peoples against the Jews, and still there is no Jewish race.

“What I state on the subject, Boni, is purely speculative, and not with the view of running counter to your ideas. How could one not believe you! Conviction has its home on your lips. Moreover, you blend in your thoughts the profound verities of poetry with the far-spreading truths of science. As you truly state, the shepherds who came from Bactriana peopled Greece and Italy. As you again say, they found there natives of the soil. In ancient days, a belief shared in common by Italians and Hellenes was that the first men who peopled their country were like Erectheus, born of Mother Earth. Nor do I pretend, my dear Boni, that you cannot trace through the centuries the antochthones of your Ausonia, and the immigrants from the Pamir; the former, intelligent and eloquent plebeians; the latter, patricians fully impregnated with courage and faith. For, when all is said, if there are not, properly speaking, several human races, and if still less so several white races, our species assuredly comprises distinct varieties oftentimes stamped with marked characteristics. Hence there is nothing to hinder two or more of these varieties living for a long time side by side without fusing, each one preserving its individual characteristics. Nay, these differences may occasionally, in lieu of vanishing with the course of time under the action of the plastic forces of nature, on the contrary become accentuated more strongly through the empire of immutable customs, and the stress of social institutions.”

“E proprio vero,” said Boni in a low tone, as he replaced the oaken lid on the coffin of the Romulean child.

Then, begging his guests to be seated, he said to Nicole Langelier:

“I shall now hold you to your promise, and beg you to read to us that story of Gallio, at which I have seen you at work in your little room in the Foro Traiano. You make Romans speak in your script. This is the spot to hear your narrative, here in a corner of the Forum, close by the Via Sacra, between the Capitol and the Palatine. Tarry not with your reading, so as not to be overtaken by the twilight, and lest your voice be quickly drowned by the cries of the birds warning one another of approaching night.”

The guests of Giacomo Boni welcomed the foregoing utterance with a murmur of approval, and Nicole Langelier, without waiting for more pressing entreaties, unrolled a manuscript and read aloud the following narrative.

CHAPTER II

GALLIO

IN the 804th year of the foundation of Rome, and the 13th of the principality of Claudius Cæsar, Junius Annæus Novatus was proconsul of Achaia. Born of a knightly family of Spanish origin, a son of Seneca the Rhetor and of the chaste Helvia, a brother of Annæus Mela, and of the famed Lucius Annæus, he bore the name of his adoptive father, the Rhetor Gallio, exiled by Tiberius. In his mother’s veins flowed the same blood as that of Cicero, and he had inherited from his father, together with immense wealth, a love of letters and of philosophy. He studied the works of the Greeks even more assiduously than those of the Latins. His mind was a prey to noble aspiration. He was an interested student of nature and of what appertains to her. The activity of his intelligence was so keen that he enjoyed being read to while in his bath, and that, even when joining in the chase, he was wont to carry with him his tablets of wax and his stylus. During the leisure moments which he managed to secure in the intervals of most serious duties and most important works, he wrote books on subjects relating to nature, and composed tragedies.

His clients and his freedmen loudly proclaimed his gentleness. His was indeed a genial character. He had never been known to give way to a fit of anger. He looked upon violence as the worst and most unpardonable of weaknesses.