Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

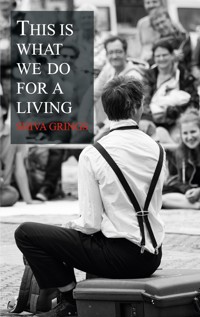

What is street theatre? Who are it's actors and where does it take place? In this humorous exploration of the scene, Shiva Grings mixes his instinct for the comical with the finesse of the storyteller, taking us on a wonderful journey into one of the least known theatrical professions on the planet. This is the second edition, published in 2023.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 412

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Part 1 – Beginnings

1. Hanging around

2. Magic

3. Amateur work

4. Galway Bay from above

5. Moustaches and grapes

6. Oliver Twist in Liverpool

7. My personal Jesus

8. Cartwheels for pennies

9. The Avenue

10. Nails

Part 2 – Switzerland

11. False teeth

12. Tea and Alps

13. Waiting for the show

14. The mannequin king

15. All work

16. On ice

17. Dean

18. Daisy and Donna

19. Northward bound

Part 3 - The learning process

20. Genitals in the wind

21. The crew

22. Drunken Singing

23. Acting the Clown

24. An ugly job

Part 4 – Busking

25. On the road

26. Generic genius

27. Mirrors

28. Creeping forward

29. The Pigeon Chaser

30. Down South

31. Puppets

Part 5 – Festivals

32. When you have nothing to lose

33. Festivities in Brazil

34. Machetes on the side

35. Trash

36. Pins and needles

37. Saint Peter

38. Epilogue

Part 1 – Beginnings

1. Hanging around

I was five metres in the air, shirtless and about to be bombarded with paper aeroplanes, when the police arrived.

There were six of them in a van that came around the corner with the siren wailing. They had been out of sight, waiting for this very moment, and now that it had arrived, they drove at a lazy speed that was at odds with the cutting scream of their blue lights. The side door opened and they spilled out onto the pavement, each one less friendly-looking than the previous. With their bulletproof vests and baseball caps, they had that peculiar Eastern-European policeman’s air that strongly discourages you from asking for help – discourages you from asking anything at all – and leaves you looking around for gangs to rescue you.

From my perch high up on the lamppost, a Barbie doll clutched between my fingers, I was relatively pleased with the knowledge that they couldn’t reach me. This fact was only dampened by the knowledge that I would have to come down eventually. Down below, I saw that one of them was gesticulating at the ground in a way that made me feel as if he were grinding an imaginary me into the pavement. Being a friendly man at heart, he accompanied his signal with one loud barking word:

“Down!”

Observing this little scene were about three hundred people, none of whom were very happy about the arrival of the police. Many of them were yelling at them with anger that came from more than the interruption – that came from a history in which corruption and oppression had not been all that far away. I could feel the pent-up rage in their rumbling: the low growl of menace vibrating through my lamppost.

Yet, always one to try the firm hand of diplomacy, I called down to my would-be jailers, “Just five more minutes!” I tried to accompany my words with a smile. In retrospect, it was probably more of a grimace as I struggled to keep my grip on the lantern.

How did I manage to get myself into this situation, caught topless clutching a Barbie doll on a lamppost in the middle of Poland, while the police debated whether to shoot me down or wait until I starved and fell? The answer – odd as it sounds – is that this is my profession. I was in the middle of a street show in the city of Wroclaw, and the mass of people gathered around my lamp were my impromptu audience. We’d barely known each other for half an hour, but already they had decided to take my side against the law. The same situation had occurred to me many years earlier in Germany, although I’d been on the ground then, and less capable of avoiding the police. The speed at which the relationship between performer and audience builds is incredible, and is equalled only by the speed with which a dislike of the law can grow upon their arrival.

“No,” my policeman was yelling, “You finish now.”

I sighed, and prayed that someone somewhere was scampering to get the festival organiser. But the city was big, and Romauld was notoriously hard to track down.

Romauld, or Romek as we all affectionately called him, was a busker himself; a one-man-band to be precise. Occasionally, when the wind blew from the right direction, he’d strap an eclectic assortment of instruments to his body and surprise us with a rendition. Watching Romauld was an unforgettable experience – like standing directly in front of an elephant while it blows its trumpet. This otherwise quiet man, whose favourite pastime seemed to be sitting with a beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other watching the performers get increasingly inebriated, turned into a raging, fuming whirlwind of energy.

Now and then, when he called out our pitches, you got a hint of the strength within him: he had a voice that could fill a room and drown out all other conversation when it wanted to. On stage, he banged, bellowed, beat and blew out a tune that was more about the pure sonic impression it left behind than the melody.

He wore a hat. He always wore a hat. I used to think he had been born with one on his head, so, when I finally saw him without it, I had to look twice before I realised that it was Romauld. His greying beard covered the rest of his face, leaving the nose and eyes to fend for themselves. The warmth and kindness that came from them was just as strong as the noise that came from his performance.

He had grown up in a different time, back when Poland was still part of the Soviet Union and the West was a strange and distant land. One of the first men to organise a street festival in his country, his reasons were the best kind – a desire to show people something new, allowing laughter into places that had, perhaps, seen little in the previous years. His festivals often toured small and impoverished towns where it was almost impossible to earn money, but easy to spread joy. In Poland he was something of an institution; a rebel due to his insistence on reclaiming the streets in a time when it was hard to express opinion.

Although an organiser, he was awkward when it came to speaking English – the language that most of the festival communication happened in – but he fought his way through this minor difficulty with the same energy he fought his way through his music. His festivals were often barely promoted, so that when you went to play on the street, most people passing didn’t even know there was a festival happening. For them, we appeared like a sudden, random influx of performers.

Therefore, although I respected Romauld deeply, I suspected that he might be some time in coming to my aid. Furthermore, I was far from convinced, even if he did arrive, that leaving my perch atop the lamp would be a wise decision.

Which left me between a lamp and a policeman. Not quite a rock and a hard place, but not far removed.

The audience was beginning to rumble menacingly. With every minute that I kept my perch the rumbling grew louder. And the louder it grew, the more enraged my police entourage became. I wasn’t sure if refusing to come down from a lamp was a crime, but I was fairly sure that being up there in the first place was.

Smart, no? my reasoning in this moment of crisis. But if you presume that my logic came from some highly developed understanding of the laws, or some instinctive understanding of the human condition, I have to disappoint you. My logic came specifically from an earlier encounter with the police during the end of my first show that day.

Back in that first show, as I developed the number to a close, I had begun to climb a building, at which point the police had magically appeared and told me to come down, an action that I had reluctantly done. That time the law had remained outside of the circle and been content with giving instructions from a distance.

When I arrived to do my second show and found their van parked right in the middle of the pitch, I should have suspected that something was afoot, but in that beautiful streak of performer’s optimism that occasionally grabs me like an unwanted illness, I put it down to coincidence. I reckoned they were parked there because they had to park somewhere. By consistently playing with their immobile faces inside of the van, and revolving the entire start of my show around the fact that they were there, I eventually managed to make the situation so uncomfortable for them that they started the engine and drove off.

At which point I naively presumed all my troubles were over, and the officers would be down some side street crying. It had never occurred to me that they could be parked around the corner, waiting for me to climb up any not-to-be-climbed objects.

The situation was only getting worse below me, and although it was a comfortable feeling to be perched above it all, removed – so to speak – from the cares of world, it wasn’t improving my chances of a positive outcome once I decided to descend. There was nothing for it but to face the music.

Reluctantly I began to climb down. Not the easiest job, as the lamp was fairly high. My crowd and my policemen waited for me below. The latter didn’t look any friendlier up close.

Once I had reached the floor one of them grabbed my arm and without wasting any further words, did his best to pull me into the wagon. I’ve always been cursed with a particularly vivid imagination, and in horror I foresaw my immediate future: dragged into the van with six burly officers, the crowd gathered helplessly around. A huge pile of menace to my left and right, another directly before me, cracking his knuckles and smiling with the kind of smile you only smile when the person at the receiving end is entirely at your mercy. “We’ll soon have you climbing up some walls, sonny boy,” he would say, barely moving his lips and with a curiously American accent. Perhaps it was this unfitting tone that wrenched me back to reality.

I planted my feet in the ground. If I thought about it seriously, I didn’t imagine any violence, but I did imagine that it would take the rest of the day for them to decide what to charge me with. And then they’d let me go and I’d be in some distant suburb of Wroclaw, completely lost with my gear missing, and Romauld would only notice three days later, while drawing up one of his maps.

So I resisted their ever-so-kind insistence that I join them in the van and repeated my one line, “I’m with the festival! I’m with the festival!”

In many a festival this would have worked wonderfully, only in this one, which always happened at the last moment and had zero advertisement, it meant nothing at all.

The big fellow was still tugging at my arm, perhaps in the hope that at least my arm would comply if not the rest of me, when I changed tactic.

“Look, this is ridiculous,” I said, “There are over two hundred people here who’ll never let you take me out of here. Let’s just agree that I won’t climb up there again.”

The officer surprised me by understanding the gist of my plea. Around us people where yelling in Polish, and no one, not even the cops, seemed happy about the way things were headed. We were already being pushed from all sides, and the cop and I had to touch noses in order to speak to each other. He stopped his tugging and eyed me sceptically.

“You don’t go up again?” he asked.

“I promise,” I replied, and almost meant it.

He looked around him. “If you go up again we arrest you,” he warned.

“Promise,” I repeated. At least not today, I added in my head.

It was a relief to feel his grip relaxing. The crowd cheered as the policemen returned to their van and slowly reversed out of the circle. It isn’t too often that the police back down, and I had the feeling it was even less common in Wroclaw than in the places I usually play.

The show was over. The crowd hung around for a while and talked to me, letting their anger fade. Once even they had gone, I was left to gather my things in a street that had returned to normal. It was as if nothing had ever happened.

That’s how it is on the street, you make a wave but the ripples are gone faster than you are.

*

If someone were to ask me what street theatre is, I would have a hard time to confine its description. Street theatre can be anything; from the old woman playing accordion to the five-hundred strong crowd watching a clown perform slow motion. It can happen in the most unsuspecting locations apparently at random, instigated by a man in suit or by a punk with piercings.

It is theatre for everyone, from the homeless to the millionaire and everything between. It harbours an eclectic audience that is unlikely to find its way into any theatre – they left the foyer and forgot about it, only to rediscover it in one of the most unlikely places: on their doorsteps, between the street cleaners and department stores.

It happens all over the world, from France to Brazil, Russia to Australia. There isn’t an hour in the day that you won’t find someone at it, yet, paradoxically, it is also one of the least known forms of theatre. People watch the shows and think we are fair-weather performers, perhaps students who need a little extra cash. They never make the equation that the fellow sitting on the lamppost might be doing it professionally. That his lamppost is one of many lampposts all around the world that have the dubious honour of straining under his weight.

We aren’t famous in the classical sense, even though we play for hundreds of thousands of people every year. For me, street theatre isn’t about fame, but about play, joy and the spontaneity of the moment.

*

“I can get you into film business,” he said, grabbing the last straw within reach in an attempt to get me to stay. “I know famous directors , met Tom Cruise once, too.”

We were sitting in a dingy jazz bar down a backwater street just off the main square in Wroclaw. It was autumn, my first time in the city, three years before I ended up on the lamppost. Smoke had stained itself into the mahogany banisters and carved a home in the long grooves of the scarred tabletops. It had settled onto every surface, like time itself, slowly wearing the sharp corners to blunt curves, dimming the veneer of grandeur past that permeated the place like a wine stain.

It lay upon Jens Stollen in the same way – some form of illness that wore through his faded clothes and weighed down the brim of his leather cowboy hat. His face was pulled by it, sagging the jowls, blunting the cheekbones, clenching the dimmed blue eyes. It was there too, in the words that grabbed at me to stay, clutching at the only person they could find to keep the ageing man company.

He lit another cigarette and offered me a replacement for the one I had just killed in the ashtray between us. I declined. It had been a long day, and although the night was still young, I was exhausted from my trip, and the two beers I’d already had were making an impact.

I’d come from Dresden, which is not such a huge distance away, but at the time there was no fast connection from the one city to the next. The train all but fell from the railroad track once it passed the border. The smooth steel of the German railway was replaced by rusting tracks and gaps between the rails that echoed through the entire carriage. We slowed to a crawl and then stopped at a sad little station from which we had to catch a bus that I suspected dated from the fifties. The doors had to be wrenched open, and over our heads bent aluminium luggage racks rattled threateningly throughout the journey.

We didn’t drive for long. The bus was merely there to take us from one station to another because the track between the two was unusable. On leaving, I was somewhat confused, since there had been no announcements concerning our surprise road trip. Up until then, I’d contented myself with the tried and tested method of following everyone else. Now I was suddenly unsure. Were we already in Wroclaw? Was this barren parking lot my destination? Because everyone else was running off to cross a footbridge, I reluctantly decided to follow. At that time I was still carrying my old unicycle and suitcase, as well as a backpack, so I couldn’t dash as fast as the rest. It was only when I saw a train waiting on the other side of the footbridge, that I realised why everyone was in such a rush. The doors were already closing, and the ancient carriages seemed about to crawl away at any moment.

Before me, an old woman in her late sixties rushed to catch the train. She was yelling and waving her arms. The conductor saw her and paused the action of leaving until she was on the platform, after which she shouted at him some more and pointed at me, still struggling to reach them. Thanks to her, I managed to board before they left. I have no idea what I would have done on that empty platform if they’d gone.

I fell asleep almost immediately once we were moving, exhausted from a grinding headache that had plagued me most of the morning. The last thing I remember seeing was an old man shaking his head in disgust as three young men shouted across the carriage at each other. The sound of the falling-apart coach was so overwhelming; it was like a blanket, covering me in a soothing wave of noise.

Over the years a lot has changed, but every time I arrive in Wroclaw, I remember the first time, stepping out of that rattling train into the crumbling station. They’ve torn it down since, replacing it with a gleaming new cement building, but back then – as they prepared for the demolition – everything was falling apart, repaired rather than renovated; make-do rather than serious attempts to fix things permanently. Grime layered the corners, cement lay bare on the walls and the smell of coal seemed to drift in from nowhere.

Within no time, I had met a group of youths fascinated by my unicycle. They were so taken by my skill (well, I could barely refuse them a quick demonstration, could I?) that they insisted on accompanying me directly to my hotel – which was a good thing, since I’d never have found it on my own. They left me there with waves and smiles and broken English.

The hotel felt like an accidental memento of the East Bloc, all vile brown carpets, faded green walls tainted with nicotine and a tiny wooden cot for a bed. The rooms were dormitories, with three empty beds beside mine. At the door a woman in worn clothes sat behind a glass screen with a small ticket-office style window through which she passed the key. Her tiny cubicle was lit up by a TV set which kept her company twenty-four hours a day. Although friendly in a detached way, she spoke no language other than Polish and possibly Russian, so communication was done in sign language and smiles.

I called Romauld and arranged to meet in a pub at nine. We got on well right from the start. In the first pub he downed his beer in one swig and proceeded to lead me to the next location, where Jens was playing Leonard Cohen covers. Although “playing” is a generous term for someone who strummed his guitar as long as Romauld was there but otherwise drank beer and sucked the life out of cigarettes.

Jens talked incessantly, rolling one long tale over and over in his mind until he found a loose thread that lead to another – a man more interested in talking about his genius than proving it.

Romauld, perhaps a veteran of such stories, made an early exit, leaving me alone with Jens. At that stage, the concert was no concert at all. There were only one or two tables occupied in the bar, and no one was listening to the old man in the corner.

Like so many of us street artists, Jens was a mix of cultures. Originally from Germany, living in Greece and just about to move his life to Denmark, he had apparently been everywhere and met almost everyone. But all his chitchats with celebrities and their stories did little to keep my attention. It wasn’t as if, by talking to a man who had talked to men who were famous, all that fame would rob off on me and I too would be famous. Despite the feeling he was trying to convey, I doubted that fame was an illness that I could get infected with if I hung around him long enough. Nor did the fact that he had talked to famous people make Jens any more famous or interesting.

But for him it was an all-consuming passion, as if he were nothing without his celebrity connections. He was a soldier in a fame war, pinning another star onto his uniform for all to see: Leonard Cohen, Van Morrison, Steven Spielberg, all across his shoulder and promoting him to a celebrity hero. The cards in his hands were all big names, and he thought he could keep the game running just with the bluff of them. But once Romauld had gone, (Jens had instantly stopped playing the minute he was out the door, and sat himself directly across from me), I prepared to leave, too. It was then that he came at me with both barrels of his fame gun blazing.

“Steven Spielberg. The Steven Spielberg. His niece, I mean, I met her...”

I left him there wrapped in smoke and his own illusions while I searched for my hotel.

He was my introduction to the oddball characters in that festival, even though I never saw him again – he just disappeared into thin air, like a modern-day Rumpelstiltskin. Once I saw through his illusions of grandeur, he vanished in a puff of cigarette smoke. But, as in many festivals that I’ve been to, the Buskerbus was no exception when it came to strange people with odd habits.

Occasionally, when I’m feeling particularly philosophical, I see us as a mismatched crew aboard a ship adrift in the small towns of the world. The ship in question is always another – sometimes a smoke-stained oak bar, pushed between warehouses and dilapidated housing blocks, sometimes a large hall that has once been a bakery. Sometimes we sleep in five star hotels, so out of place that we are an eye-sore to the staff, other times we sleep six to a room in a hostel.

The crew consists of almost everyone; Argentinian clowns with large shoes, Polish puppeteers with worn props, Australian gold miners with sonny-boy smiles or acrobatic trios complete with five year old son in tow. Everyone a personality be it loud, quiet, egocentric or solitary. Some are there for the money, some for the adventure. They come from all walks of life and wash up on the shores of the street like so much driftwood.

Just like me.

2. Magic

It must have been 1986 when I was handed my first juggling balls. They were red and white hackie-sacks with smilies on them. I can’t recall the person’s name, but he’s responsible for me sitting on lampposts in Poland.

I suspect he only gave them to me because I was getting in the way. He had a market stall in Galway, Ireland, and since I was there most days and liked to be entertained (if not entertaining somehow myself, as an eight-year old tends to do), he gave me the hackie-sacks and showed me how to get them air-born. The next week saw me standing against a wall (which was the only way I could ensure the damn things stayed in front of me instead of dashing all over the place) and tossing them into the air. Six years would pass before I made use of my newly discovered skill, but it had been sown, that little seed of disruption.

I used to sit in Eyre Square and watch the performers do their shows. I thought that Eyre Square was the biggest, boldest public space the world had ever seen. It was everything: lawn, square, public toilets and forest (it had trees at the corner). Even John F. Kennedy, Master of the entire Universe, had been there once. I often wondered which urinal he had used. They all stank, but was there one with that special presidential air? (Ronald Reagan visited Galway once, too. All I remember of that visit was that someone threw an egg and the security police raced down the street after him.) When I go back there nowadays, I’m constantly surprised that Eyre Square is so much smaller than I remember. I keep expecting it to suddenly spread out to ten times its size and say, “Fooled you.”

They tried renovating it once, just after the boom times hit. It took a year for them to dig it up until it resembled the trenches of the first World War. In that state it stayed for such a long time that people began talking about the Zoo when discussing the square. One day, after the contractor had somehow managed to blow all the money, he hung up a sign saying, “I quit” on the fences, and left it to its own devices. The last I heard of him, he was in France, probably sipping Champaign on the Riviera and worrying about his tan. The local newspaper printed a photo of the unexpectedly unemployed builders standing at the fence with bewildered expressions.

The city is inflicted with the most eclectic weather mix that I have ever experienced. In other locations around the world, the weather tends to make firm decisions. It wakes up in the morning and says, “Today I shall be cold,” or “Today I will rain,” and lo and behold, that’s what happens that day.

In Galway the weather is an indecisive, hyperactive junkie. It rises and says “I shall rain today,” but changes its mind half an hour later saying, “No, that’s a bad idea. I shall be sunny instead.” It isn’t long before another mood swing comes across it and it says, “Why, I have not seen sleet and snow in a long time, that’s what I shall be today.”

And so on and so forth every day of the year. When you grow up like that, you start to get edgy outside – there’s no natural trust between you and Mr. Weather. You eye it with suspicion and prepare for everything. For street shows it can be a real nuisance, since you might be in the middle of a wonderful show when a sudden rainstorm chases your entire audience into the nearest pub.

All the same, for some reason best known to themselves, a series of street performers sailed across the Irish Sea from England and did shows in the square on Saturday afternoons. Not a lot, if you compare it to somewhere like Covent Garden, but half a dozen semi-decent shows. I never talked to them. They were like John F. Kennedy – Gods of another planet who’d eat my head off if I as much as uttered a single word to their air around them.

I did my best to never miss a show. This was something so new to me I can only compare it to seeing sunlight after living in a cave.

Not that Ireland was a cave, but it was so different from the world of these performers. In the winter the river flooded the street, and with it came swirls of toilet paper and excrement because we didn’t have a water treatment plant. I had no idea what McDonald’s looked like, or H & M. The first time I saw a black man was in the nineties, and I remember that I had to force myself not to stare too long. Trains left occasionally and buses when they felt like it. The houses were often colder than the world outside and, with all the wind, I had no idea why anyone would use an umbrell0. For me, they appeared to be things that you bought merely to put inside-out into street bins. We had two television stations and two radio stations, and if you were on one of them, the entire world and his daughter knew you. When the radio truck came into town, we’d scramble around it like it was free candy-floss.

Not to say that we were cut off from the outside world. Everyone who came to Ireland past through Galway sooner or later, and most of them decided to stay. We had American tourists and Australian backpackers milling around us with cameras and smiles and words like, “Quaint”. The Americans felt they belonged there, since their great grandfather’s dog had come from Ireland, while the English liked the social welfare the state seemed to be eager to hand out to them.

Originally I’d wanted to become a magician (actually, I wanted to become Asterix, but I could neither find any Romans to fight nor any wild boar to eat). I imagined myself in a tuxedo somewhere making buildings disappear and replacing them with peacocks while the crowd “oooh”ed and “aaaah”ed. It reminded me of all the fantasy books I’d read, and I saw myself as a modern day Gandalf.

For some odd reason that only appears odd to me now, the only place I could learn magic in our town was in the Pet Shop. This was a tiny shop squeezed into Quay Street with one window packed with bones and leads and whatever else you put into pet shop windows. Inside it was barely wide enough to stretch your arms without knocking over a spider tank or a birdcage. There was a smaller room in the back that held a line of aquariums and the sound of the filters was a constant backdrop to my magic lessons.

The pet shop owner was a member of the Magic Circle of Ireland, which sounded to me like a clandestine group of rebels passing on a long history of magic. He’d amaze me with card tricks and coin manipulation whenever I visited, making things appear and disappear at will. His daughter was in her twenties and seemed uninterested in his fantastic skills. What a stupid daughter! Here was a man who could turn a five pound note into ten, and she just sat at the side and stared at the spiders.

Of course I wanted to learn to do the same thing, but whenever I asked how he did it, he just winked and said, “That’s magic.”

Well, of course it was magic, I thought, but couldn’t I learn it, too?

The problem was, I could learn it, too. He offered me the tricks whenever I asked, but to buy the trick of changing fivers into tenners you had to pay a hundred pounds. I wouldn’t need to change fivers into tenners if I already had that much cash.

So apart from a few books that my mum bought for me on the subject, I didn’t get far in the world of magic. When I met jugglers, however, and asked them how they did stuff, they never winked and said, “That’s magic.” They’d say things like, “That’s a two-count, left, right, double.” So I began to hang around them instead.

When I was sixteen or so, I took myself to the furthest most unlikely corner of Eyre Square and juggled behind a statue. A man and his one year old daughter watched me and dropped eleven pence into my hat.

I was a made man! I had earned my first busking money, and the road before me had opened up like a highway. I was a busker, a performer, a juggling clown not all that far removed from the shows that filled Eyre Square every weekend. I could entertain the masses – at least two people at the same time, if you counted the one year old (who, admittedly, was more interested in picking up my hat than watching me). I had the whole world at my feet!

I treated myself to a packet of crisps, which cost twelve pence.

From that moment onwards I began juggling all the time, as well as learning the diabalo, devil sticks and unicycling. I wanted to learn it all.

There was a small scene that began in Galway at that time, partially pushed by the fact that a juggling shop called Butterfingers had opened up in our flashy new shopping centre in the middle of town. Whenever I was in town, I hung around there and learned tricks, bought juggling equipment and bothered the owner, a dread-locked ex-hippie called Nick. Nick sold me all kinds of things, juggled with me and generally found ways to pass the time inside his booth. Once upon a time he had been a street performer, busking on the streets of the world, but for some reason he had landed in Galway, and there he had stayed, opening up a juggling shop instead of busking. Eventually he gave that up too, and the last I heard he was a professional photographer. He was the first performer I ever met with a business postcard.

The scene revolved around the shop, although Nick wasn’t in the scene. He was at its periphery, selling gear but keeping at a distance. The rest of us met up in Eyre Square most Saturdays and juggled together. A few of the people there continued in the business and became relatively well known in Ireland. Me? I eventually disappeared onto the Continent, which was, in terms of Galway, like being shot into outer space.

I guess I became a magician, after all: I took a bow and vanished into thin air.

3. Amateur work

I knocked on the door of 131 Bohemore and waited. Behind me the cars crawled into town for the morning rush, moving as quickly as turtles on a Sunday stroll.

They moved like that every day, three times a day. Ireland had lacklustre public transport, which ended up with most people taking their car into traffic jams for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Bohemore was one of the main arteries into the centre. The small rise that seemed to take a breath before dipping into the centre was lined with squeezed-together houses so tiny you would be forgiven for thinking dwarfs had build them. Like 131, most of the houses consisted of one room at ground floor and another above it. Both rooms were somewhere around fifteen square metres.

Graham opened the door, somewhat dishevelled, as always, his pony tail tied behind him.

“Ready?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied in his British English. The gear was stacked in the room, as I saw once I had ducked through the door and found myself in the tight apartment. The room smelled of cannabis (Graham had a nice little plantation in the back which he tended with a mother’s care). There was the smell of coal too, since the stove that gave the cubbyhole its heat was in the same room. The rest of the first floor was covered in an eaten away couch and some stools. If I stood on my toes, my head touched the roof.

This little room had been the scene of many an afternoon. Although PlayStations didn’t exist in those days, I’m fairly sure our days would have been spent playing one if they had. As it was, we drank tea and chatted about juggling. We never smoked anything – Graham was always very tactful in that regard and kept his gardening habits to himself so as not to tempt my innocent self. He was in his mid thirties, from England and living in Galway for the last couple of years.

Today was to be a very special day. Today would be our first and (although we didn’t know it, then) last show together. Props in hand, costumes in place, we took the car and drove to the Sligo Street Festival to premier our one and only show.

“What should we call ourselves?” I asked, after the decision had been made.

“It has to relate to something we can do,” Graham mused.

We sat in silence for a few moments, puzzling over the range of things we could do, and over the greater range of things we couldn’t. “Not a Lot,” didn’t seem like a good name.

“We’re amateurs at this game,” Graham pointed out. “Maybe we should just admit to it and call ourselves the Amateurs.”

“Amazing,” I said, happy to have found a solution.

“Okay, the Amazing Amateurs it is, then,” Graham agreed.

And so the Amazing Amateurs were formed.

I wore my best clown suit, although I didn’t realise it at the time. I thought I was dressed rather coolly in my Indian waistcoat complete with tiny mirrors, tie-dye t-shirt, baggy pants and sweatband. The sweatband was holding back my shoulder-length hair and made me look like a cross between a hippie and part-time jogger. Thankfully for Graham, my mind goes blank when I try to remember his idea of style.

We’d bundled together every trick we had and devised a show around it. We played two opposing performers competing for the same pitch. The show took place on a tiny pavement almost nose to nose with the audience and won second place, a feat which would have been of greater importance if there had been any other shows there. The other performances consisted of kids playing music on street corners. Back in those days, few people in Ireland had ever seen a circus-based street show. We were a novelty act.

Our tour took us far away from home – Sligo is a good 140 kilometres from Galway – and we were never the same again.

I was one step closer to my goal of being a real street performer! In my mind we were international stars now, admired (or at least looked-at) by dozens of people at the same time, winning prizes and on the road almost all the time (the better part of the day was spent on the potholed tarmac between the two towns). We were surrounded by women, or at least Graham was, because his girlfriend drove with us, and followed by the Paparazzi (there was a photo of us in the local paper). Nothing could stop us now.

Driving home I’m sure we planned out or career, yet somehow it never happened. Perhaps it was the fame that tore us apart, or perhaps we just couldn’t agree on the next production, whatever the reasons, the Amazing Amateurs remained a one-off event. Graham and me went back to drinking tea and juggling in Eyre Square, the plans of another tour forever around the corner.

Galway was a place in which a lot of things were forever around the corner.

*

With the Amazing Amateurs in early retirement, I was at a loss at what to do. I tried my luck in Eyre Square now and then, but the location was too difficult for me. There were too few people there, and those that were, couldn’t be convinced to form a decent crowd. Was my performance life over?

My family had come to Galway in the beginning of the eighties, washed onto the coast like shipwrecks in reverse – they ran out of land to sail across and capsized against the shores of the ocean. Like many foreigners that I met as I grew up, they enjoyed the lack of European bureaucracy. It was a country in which nothing was checked – the most important thing you needed in order to survive was a will to do so. Throughout the rough countryside of Connemara, where I grew up, there were pockets of like-minded ex-hippies, ex-anarchists; full-time dreamers. Some built their own houses, others grew their own vegetables, others home schooled their children.

My family was one of the latter, and all four children passed our younger years without setting foot into a class room. My mother taught us the basics of maths, English and history, but most importantly, independent thought. In those days we lived in the countryside, far from the prying eyes of government officials, but even if we had been in the city, home schooling was perfectly accepted in this country full of religion-dominated, single sex schools.

I used to watch school kids in vague bemusement as they ran out of their school yards, screaming and yelling. Their school lives were so strictly gender separated, that they consequently ended up creating more little boys and girls the minute they finally met up. To my untrained eye, there appeared to be three pregnancies to every school yard.

Home-schooling was all fine and good in the early years, but it left me at a loss later on. Luckily, in the Ireland of those days the most important qualifications were your desire to do something, yet you still needed to know what to do, and I had absolutely no idea. I had some vague hopes of becoming a famous author, but what was I going to do to tie myself over in the meantime?

Ireland was also the land of the Chancer – a term we use for someone who will try anything. Builders would claim to be plumbers in order to get a lucrative contract, plumbers would use water-soluble glue if they thought no one was watching while rubbish was furtively dumped behind every bush. This aspect of life continued into the art scene, resulting in musicians busking as soon as they could play “Wonderwall”.

Strolling through town one evening, bullied by a persistent wind and the occasional splatter of drizzle, I pondered my problem. If I wasn’t going to be a famous author soon, then I should attempt something different to get money. Working Eyre Square wasn’t helping me either, since it was only possible on weekends and when the weather was good.

Shop Street wasn’t pedestrianised back then, but had a thin trail of cars going West along it. During the day, the pavements were jammed with shoppers, but in the evenings the crowds thinned. With the stores shut, their entrances became small alcoves in which musicians played. No one got any crowds, but people walking past on their way to the pub seemed to drop coins regularly.

I could do the same. I couldn’t play an instrument, but I could stand on a corner and throw things in the air.

It wasn’t a bad way to make some money, but it was still difficult to get a crowd. In fact, I noticed that the less I tried to get a crowd, the more often people dropped money while passing. And I noticed something else too: the later I began, the more drunks came along, and the more drunks, the more I got paid.

And so began a gradual process that turned me into a night owl. Deterred from the afternoon pitch in Eyre Square, I began to juggle once the shops closed, then up until dinnertime and finally well past midnight. Without fail, the later it got, the more the people paid me. It was as if every beer someone consumed added fifty pence to what they would put into my hat. And in return they wanted nothing at all, just one quick trick and they were happy.

Of course, I still had to get their attention. Since I wasn’t a musician, therefore not very loud, I had to use another method. Despite being relatively good at juggling, juggling didn’t seem to interest anyone all that much. So I decided to become worse at juggling.

It was a simple enough ruse: as soon as a group walked past, I accidentally let a club fall to the floor.

And the game was afoot!

Now they noticed me and they thought they could do better, tried to toss it between themselves, picked it up again and to everyone’s sheer delight, tossed it directly at me. Of course, they thought, I’d miss like they did, but no! I caught it! Victory!

What skill! What applause! The man was a genius!

My victims would drop something into the hat and wander further into the night, and two minutes later I’d repeat the same trick.

It was like picking apples in an orchard.

The first rush was around nine in the evening. This was the least profitable of times, since no one had been to the pub yet. But they were on the way to it in their droves, one group after another seeking out the location of their inebriation.

The second rush came at midnight. The pubs, all forced to shut due to stringent closing hours, locked their doors and kicked out the customers. Now, if you weren’t already completely drunk you only had one choice left, to make it to a nightclub before they too closed – on the way, give another pound to that funny fellow who keeps dropping his pins.

The third rush was between two and three. This hour was populated by the completely drunk, utterly in love or bitterly disappointed. This was the riskiest time to be out yet one of the most profitable. Sometimes I could sense that someone was looking for a fight, and I’d busy myself with something so as not to get his attention. Apart from one man tossing my club so high into the air that it got stuck on a roof, nothing ever happened to me.

I walked home as the queues at the taxi stands began to form. Most nights I had to tiptoe over sleeping drunks on the pavement, and avoid the vomit that littered the streets like irregular stars – Galway’s very own version of the Walk of Fame.

Before I went to sleep I counted my money, placing it into small piles of each denomination. My silhouette on the curtain probably had similarities to that of Ebenezer Scrooge.

*

To my luck, they pedestrianised Shop Street.

It took a long time. No one seemed exactly sure who was responsible for the job, not even the builders. They’d stand on the street, six to a hole, smoking cigarettes and waiting for a digger-load of pebbles. The minute it arrived, all six would shovel it into the gap within a minute, lean back and wait for the next load to come in. After a year they had the surface covered, only to discover that the pipes leaked. With much embarrassment the city admitted to hiring the same company who specialised in tiling the floor to install the plumbing. So they dug up great chunks of the street a second time and began all over again. Two years after beginning, Shop Street had been completed. The distance paved was less than four hundred metres.

The closing of the street allowed me to play shows in the city centre instead of only in Eyre Square, which turned Galway into a busking heaven. In Shop Street there was always the chance of a show, especially on the weekends. If you tried hard enough, you could drum a crowd together, show them a trick and collect money on any day of the week. At the time, I was the only juggling show, and as such, I had the freedom of the pitch. Occasionally, someone would come over from Dublin or England and do a stint of a week or two, but most of the time it was just me.

Apart from during the Arts Festival: the Galway Arts Festival was Galway’s biggest cultural event, if not Ireland’s. It presented a wide range of in-door shows, from physical theatre, clown to music. With Race Week just behind it, Galway burst at the seams trying to contain all the visitors that arrived merely for those two events.

Alongside the tourists came the circus – the street circus. Shows would happen every evening, some amazing, some mediocre. There were slack-rope routines and acrobatic numbers, unicycle and fire shows, dancers, musicians, mimes, statues and plain oddballs. Like a delayed spring, the Arts Festival turned Galway into a multicoloured paint-bomb full of life. In every pub, on every street, people were sitting outside and telling the tallest tales and the dirtiest of secrets, and no matter where you went, you could never be sure that you wouldn’t be ambushed by a random growth of culture.

This was an amazing time for me. Seeing other performers taught me what was all possible on the street, and not just on the street but on my street.