Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

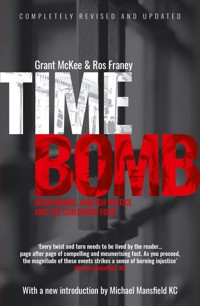

Fifty years after the Guildford bombings, the case remains profoundly relevant today. This new edition is completely updated and revised with startling new material. The Guildford Four endured 15 years behind bars for a crime they did not commit. The only evidence against them was their confessions extracted through intimidation and violence. Three Surrey police officers were acquitted of wrongdoing in 1993, but as this new edition reveals, there is testimony, never published, that corroborates evidence of far wider police malpractice. Time Bomb was central to the reopening of the case of the Guildford Four when it was published in 1988 – exposing this egregious miscarriage of justice, and telling the chilling parallel story of the men actually responsible for the bombings, the London Active Service Unit, whose 1974-75 IRA campaign terrorised Britain. Profoundly relevant today, as Michael Mansfield identifies in his introduction, the case of the Guildford Four is essentially the prototype of the corruption and concealment scandals which have beset the UK, from the Stephen Lawrence case through to the Post Office scandal, and asks how we can galvanise reform. 'Every twist and turn needs to be lived by the reader… page after page of compelling and mesmerising fact. As you proceed, the magnitude of these events strikes a sense of burning injustice.' Michael Mansfield

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 532

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

TIME BOMB

Irish Bombs, English Justice and the Guildford Four

Grant McKee and Ros Franey

Author’s Note

I got caught up again with the Guildford case in 2020 when I started to follow the manoeuvres surrounding the inquest into the deaths of the bomb victims.* As pre-inquest hearings progressed, I grew increasingly uneasy: the object seemed to be to throw as little light as possible on the case’s shameful history. Indeed, early in the process, 700 files due for release to the public in January 2020 were removed by the Home Office from the National Archives and will now remain secret until late this century.

I and my co-author, Grant McKee, worked on three ITV documentaries about Guildford in the 1980s and published the first edition of TimeBomb in 1988. After the release of the Guildford Four in 1989, except for staying in contact with some of the families, I had only a general reader’s knowledge of what happened next. Returning to it 30 years later, I realised that the startling injustices of the case, far from being resolved when the convictions were quashed, had proliferated down the years. It seemed necessary not to let Guildford slide out of the public consciousness – particularly in the light of virecent miscarriages of justice which have been allowed to persist over decades, despite the apparent ‘reforms’ after the Birmingham Six, Judith Ward’s wrongful imprisonment for 18 years for the M62 coach bombing, and other infamous miscarriages of the 1970s and 1980s. In this 50th anniversary year of the bombings, I hope that, in revisiting Guildford’s legacy of injustice, there may be some lessons for the future.

There is plenty to learn. This new edition reveals that the Bomb Squad knew the identities of the IRA active service unit even before the original trial in 1975 – and that they had no discernible connection to the Guildford Four. The information was passed to the DPP who chose not to share it with the Defence at the trial. After the Four were released, following findings of serious misconduct during the original interrogations, three Surrey Police officers were acquitted of wrongdoing in 1993. Yet the investigating police force obtained testimony alleging more extensive malpractice in Guildford Police Station back in 1974 than was previously thought. The public inquiry set up under Sir John May declined to investigate this new evidence. It was never published and is locked away with the other files.

None of this can bring comfort to any of the victims of the Guildford and Woolwich bombings: neither the families of those who died; those who were injured; nor the Guildford Four and their alibi witnesses, who have continued to suffer throughout their lives from their appalling experiences.

The other great sadness is that my co-author was not around to work on the new edition with me. Grant died in 2019. Any errors, therefore, are mine alone.

Ros Franey, April 2024

* See Chapter 37

Contents

Introduction

michael mansfield kc

The devil is in the detail of this extensively revised book. A taster, let alone a summary from me will not do it justice! Nor a commentary, which would destroy its impact. Every twist and turn needs to be lived by the reader, as it was written originally, and in the manner it has been updated, page after page of compelling and mesmerising fact. It’s the only way for generations who were not born in the 1980s, and also for those who were, but whose memories have naturally faded in the mists of time. As you proceed, the power and magnitude of these events unerringly strikes a conscientious chord and a sense of burning injustice. These essential responses are frequently bypassed and replaced by a list containing shorthand references to the Guildford Four and the Maguires, along with others like the Birmingham Six, the Tottenham Three, the Cardiff Five, the Bradford Twelve and the Newham Seven.

What is important to remember in each of these cases, however, while you read this magnum opus, is that there are noted core similarities within all of them. The point is that the risk of repetition, unless lessons are learned and driven home, is ever present. It is only through the vigilance of the public, 2and particularly those most affected, that change of any kind can be inaugurated.

In case you think for one moment that the relevance of this is all old hat and everything has moved on, rest assured that human frailty and tainted mindsets have a nasty habit of reappearing in later generations – for example, the inquiry into the imprisonment of Andrew Malkinson, who spent seventeen years in jail for a crime he did not commit. Unless these faultlines are spotted early and rectified effectively, the quagmire of injustice will continue to reverberate and inflict untold damage. Examples follow in the paragraphs below.

It’s not the system which uncovers the faultlines but the victims, their families and friends. They combine to relentlessly fight the forces of prejudice and preconception. In each case they wring change from a recalcitrant, myopic authority which has been blinkered by denial. A matter starkly illustrated by Sir John May, who was commissioned to conduct an inquiry into the events so graphically described in this book, and is quoted on p. 347:

The miscarriages of justice which occurred in this case were not due to any specific weakness or inherent fault in the criminal justice system itself, nor the trial procedures which are part of that system. They were the result of individual failings on the part of those who had a role to play in that system and against whose personal failings no rules could provide complete protection.

Fortunately these sentiments bear little relation to reality and have been overtaken by a structure of rules and procedure that has rendered the recurrence of false or forced confessions a rarity. The full truth, however, about police malpractice 3has yet to surface, as the relevant police reports are still being withheld from the public for some seventy years!

To recapitulate for a second, the real point here is – it’s not over, by any means – that it’s the focus which has changed. The malaise described in this book has spread way beyond the confines of the criminal justice system. The familiar themes of extensive delay, despicable lies and deceit, lack of transparency and candour, deficient investigation, preconceived outcomes and unaccountability have been brought into the open by another generation of citizens. This time it goes to the heart of our democratic system, its very essence – the rule of law.

Flagrantly ignored by those in power (for example, ‘Partygate’ during Covid lockdowns, to Boris Johnson’s unlawful attempt to bypass the authority of Parliament in the hope of gaining a no-deal Brexit, to the procurement of NHS Covid contracts, to deportation of refugees to Rwanda), the themes outlined in the paragraph above have been laid bare in a series of momentous public inquiries and inquests, which have been brought about by the pressure of the victims and the public, with their origins coinciding with the same period as the observations by Sir John May.

The increasing and welcome deployment of cameras in the most recent hearings has enabled aspects of the evidence and the findings to shock public consciousness into demanding root and branch accountability and change. It’s a recognition that there has been too much, prevailing for too long, and that a bit of sticking plaster here and there, some tinkering with mechanisms, and even a change of government will not cut the mustard.

The Post Office scandal is now well-trodden ground. The story is on everyone’s lips thanks in large measure to the ITV series focusing on the singular efforts of the beknighted Alan 4Bates, amplified by the regular news transmissions from the hearings showing the ineptitude – and worse – of critical personae in this dark and devastating drama. Where innocent citizens were convicted, lives destroyed, truth distorted and hidden, and where deceit became the hallmark and mode of governance.

Running alongside this has been the Infected Blood Inquiry. This one has come to a conclusion with a verdict which is excoriating. Like this book, it needs to be read in full for its ramifications to be appreciated and correlated with the book itself. Thirty thousand patients between 1970 and 1991 contracted HIV and hepatitis C from treatment which included contaminated blood products. Three thousand died.

On 24 May 2024 when the report was published, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was compelled to admit that the

report shows a decades-long moral failure at the heart of our national life. From the National Health Service to the civil service, to ministers in successive governments … at every level, the people and institutions in which we place our trust … failed in the most harrowing and devastating way. They failed the victims and their families – and they failed this country.

The speech and the report highlight the fact that it was known these treatments were contaminated and therefore the calamity was avoidable. Repeated warnings were ignored.

Some government papers were destroyed to make the truth more difficult to reveal – in short, a cover-up. ‘And throughout it all, victims and their loved ones have had to fight for justice … fight to be heard, fight to be believed, fight to uncover the whole truth.’ Those who died never heard how this 5came about, never saw any accountability and never received any apology – a shockingly familiar narrative.

Small wonder the prime minister labelled it a ‘day of shame for the British state’.

But there is yet more of similar ilk to come, with the Grenfell Fire report (unpublished at the time of going to press), and then, much further down the line, reports from the judicial inquiries into Covid-19 and undercover policing.

If these various developments are aggregated with some better-known scandals that have gone before – for example, the institutional behaviour concerning the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the Marchionessdisaster, Bloody Sunday, Hillsborough and the Ballymurphy massacre – the overall picture from Guildford onwards is abundantly clear.

Basic principles of good and fair governance have been ignored. They need to be reinforced, reinvigorated and restored as effective criteria against which the actions of public authorities may be measured. The Nolan Seven Principles of Public Life were enunciated in 1995, near the beginning of the period with which we are dealing. The Parliamentary Committee on Standards in Public Life was established in 1994 as a cross-party advisory group to compile a code of conduct, for the first time confronting and addressing culture rather than process. There was an urgent need then, as there is now, to restore trust and faith in a desperately failing system.

The seven principles relate to selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership. Four of these have a particular resonance and applicability here. Integrityis defined as the avoidance of obligations to people or organisations that might try inappropriately to influence work; by decision-making that does not seek to gain financial and other material benefits; and the declaration and resolution 6of any interests and relationships. Accountability– holders of public office (which applies to all the examples cited here) are accountable to the public for their decisions and actions and must submit themselves to the scrutiny necessary to ensure this. Openness– decisions must be taken in an open and transparent manner and information must not be withheld unless there are clear and lawful reasons for doing so. Honesty– holders of public office should be truthful(!).

Now apply these criteria to the Guildford case: the refusal of Sir John May’s Inquiry to explore allegations of far wider corruption within Surrey Police, as revealed in the final chapter of this book; or the force’s recent failure to investigate ‘new’ forensic evidence – a blatant breach of honesty, transparency and non disclosure. In a sense it is astonishing that the principle of honesty has to be set out in writing, let alone embodied in legislation. This has been the demand by the Hillsborough families with their proposal for an enforceable Duty of Candour in a Public Accountability Bill. There is a common-law duty but it is ill-defined and ineffective.

It should not require a massive miscarriage of justice or disaster to galvanise reformative action brought about by the pressure of the beleaguered. Waiting for a judicial public inquiry, essential though they are, is very much at the behest of government and can be tortuous and long-winded. Boris Johnson delayed, stalled and obfuscated as long as he could to avoid the consequences of the inevitable investigation into the Partygate scandal – in the end, his own departure.

Other avenues for challenge by citizens have been made virtually impossible by prohibitive costs and an overstretched legal system. Most civil remedies, as Sir Alan Bates has pointed out, are not possible without funding from the private sector or from crowdfunding platforms.

7The vision of a state that provides a welfare safety net and pays due regard to the rule of law has been shredded and is now derided as some form of evil ‘wokery’. The malaise is deep-seated and requires the strength and common purpose displayed by the central figures in this book.

Another time bomb.

16 June 20248

1

A Funeral in County Clare

‘This is something deep in their hearts; inherent in their blood. I tell them what is right but I cannot force them on to that path. I pray to God that it will end.’

father michael keating, parish priest, Feakle, County Clare

If Harry Duggan had really been dead, Father Keating should have officiated at his funeral. Harry was a local boy, approaching his 21st birthday when, in the autumn of 1973, Harry Duggan senior was informed by the police that his son had been killed. Details were sketchy, but it seemed there had been some sort of explosion across the border; a Provisional IRA bomb had detonated prematurely; Harry had been involved; Harry was dead.

The funeral was said to be so private that neither Father Keating nor Harry’s parents were invited. An unmarked grave apparently appeared overnight in Feakle Cemetery, and it was put about that Duggan had died on active IRA service, 10that the burial had been kept secret to deprive the British of a small propaganda victory and to preserve the morale of other volunteers.

Perhaps there had been an explosion, and some young Provo had been blown to unrecognisable bits on top of his own bomb – but it was not Harry Duggan. Duggan – very much alive – protested years later* that this was no cunning plan by the IRA to give him a new identity, but a mistake by the police, which he immediately sought to correct by getting in touch with his father and a member of his local community. ‘Hardly the actions of somebody trying to fake his own death,’ he pointed out.

Whatever the truth of it, the ‘faked death’ story was widely reported, finding its way into articles and books – including the first edition of this one – as well as being taken out of the local community by informers and passed on to the security forces. In consequence, whether by accident or design, it provided its subject with a new persona: now known as Michael Wilson, volunteer Harry Duggan was ready to go on active service again.

The IRA Army Council was assembling a crack team for a job on the British mainland, chosen by one of the least known but most important Provisionals of the 1970s, Brian Keenan. At 32, Keenan was the Dublin-based quartermaster of the entire Provisional IRA effort. In 1973 he was entrusted with a new role by Dublin command – that of director of operations for mainland bombing and, in particular, with forming the Provisional IRA’s next London Active Service Unit (ASU). This was not going to repeat the mistakes of the Price sisters fiasco earlier that year, when several members of a bombing 11team, including Marian and Dolours Price, had been arrested at Heathrow awaiting take-off for Ireland just as three car bombs were primed to explode in central London. To have the bombers attempting to leave Britain on the day of the bombings, albeit before the bombs were due to explode, had been incompetent planning. The sealing of ports and airports was always the first reaction to any suspected terrorist activity on the mainland.

Keenan’s plan was to put together a team with the patience and skill to integrate themselves fully into living in London full-time, like secret agents behind enemy lines; not a one-off hit-and-run team but an undercover unit which could sustain a long-term bombing campaign and survive long spells of inactivity. Except in dire emergencies, they would have no contact with the established Irish Republican movement in London – a prime target for Special Branch monitoring. They would operate on their own initiative as far as possible to minimise contact with Dublin and the risk of being uncovered by informers. They would select their own targets and times, working to a predetermined strategy of hitting military, establishment and economic institutions. Details of fresh targets, as well as supplies and funds, would be brought into England by couriers. Keenan dispatched a former British paratrooper, Peter McMullen, for the initial military reconnaissance.

The men chosen for the ASU would have to have minimal ‘form’ and would come preferably from the South, from the Republic. So many young men in Belfast and Londonderry were routinely picked up and ‘screened’ by the security forces regarding their and their friends’ movements that volunteers from the North represented an unacceptable risk. This also suited the Belfast commanders, who had no desire to offer up their best volunteers for a Dublin plan when they were 12stretched to the limit by internment and the courts. In 1973 and 1974 the authorities had charged 2,700 people from the North with terrorist offences. Nevertheless, the preference for using men from the South was not exclusive; Keenan himself was a Northerner.

He wanted men of commando quality and his trawl concentrated on the south-west triangle of counties Clare, Limerick and Kerry, where the IRA’s roots ran back to the beginning of the century. In his view, the most reliable men came from families with an unbroken tradition of Republican action and sympathy; men with cross-border experience who were unknown to the British security forces. A shortlist of 20 was drawn up and vetted by the Army Council. Initial training was borrowed from the British Army. The men were dropped in open countryside and instructed to survive by living rough for three days. A more selective explosives course followed.

The principal members of Keenan’s new ASU all had experience in laying mines and placing bombs across the border in the ‘bandit country’ of South Armagh. Each agreed to an undercover assignment in London, with an option of pulling out after three months.

They were Harry Duggan, now 21, of Feakle; Martin Joseph ‘Joe’ O’Connell, 21, of Kilkee, County Clare; Edward Butler, 24, of Castleconnell, County Limerick; Brendan Dowd, 24, of Tralee, County Kerry; and Hugh Doherty, 22, originally from the Irish Catholic estate of Toryglen in Glasgow, but brought up principally in County Donegal. They became the hard core of the London ASU, but there were more to be added to their number. Two young and trusted women were lined up as the main couriers. Graine Cooling, 28, of Dublin was appointed co-ordinator. She was valuable to the unit as she had lived in Harlow, Essex, from 131970–74 and worked for the architects’ department at the Harlow Development Corporation. They would operate a classical cell structure. As few people as possible, even in the highest echelons of the IRA, would know who they were. They were destined to become the most devastatingly successful team the IRA has ever assembled.

Harry Duggan’s background was typical: his upbringing with two brothers and a sister in a stone farmworker’s cottage in the backwoods of County Clare; remembered in his village as quiet, law-abiding and baby-faced. He was six feet tall, athletically built and good at sport and carpentry, following his father as an apprentice in the Scariff Chipboard kitchen furniture factory. Sometimes he shared a flat with Joseph O’Connell in Lower Market Street in the county town of Ennis. He knew Eddie Butler too. Then he went on a trip to Dublin and apparently never went home again. His mother, Bridget, who had separated from Harry Duggan senior, had not seen him since 1970.

The transition from country boy to effective fighter was fast. One exploit soon after his ‘death’ marked him down as being of the required calibre for Brian Keenan’s ASU: he was part of the team who pulled off one of the world’s most lucrative robberies.

On 26 April 1974 four armed men and a woman rang the front doorbell of Russborough House in Blessington, County Wicklow, the stately home of 71-year-old Sir Alfred Beit, heir to a South African gold and diamond fortune, a former Conservative MP and, more famously, the owner of one of the world’s most valuable art collections. The IRA burst into the hall and within five minutes had rounded up the Beits and five members of staff, dragged them into the library at gunpoint and tied them up with nylon stockings. They 14then deactivated the alarm system and proceeded to cut 19 Old Master paintings from their frames with a screwdriver. The paintings included three Rubens, two Gainsboroughs, a Goya, a Vermeer and a Velázquez. Within a further five minutes the gang had escaped in a silver-grey Ford Cortina. The paintings, valued at between £8 million and £10 million, were obviously impossible to sell, and three days later came a written ransom demand for £500,000 and for the return of the Price sisters and two of their colleagues from English prisons, where they were on hunger strike, to Northern Ireland. The demand was ignored, and ten days after the robbery the haul was recovered at a rented cottage in Glandore, County Cork. Harry Duggan was never associated with the crime.

Duggan went to war against the British with a sense of injustice partly instinctive and partly inculcated. He was now set on an irreversible course of multiple killings that could lead only and surely to years in a British prison, a sacrifice for the cause. He must have known it and embraced it. His colleagues were much the same.

Joseph O’Connell’s parents were County Clare farmers and the family lived in a little blue-and-white bungalow outside Kilkee, overlooking the Atlantic near the mouth of the River Shannon. The area is a stronghold of Gaelic-speaking inhabitants and old-guard IRA sympathisers and active Republicanism was well established in the family. Joseph was a ready learner. He had no difficulty in getting a job as a radio operator and electronics trainee at Marconi in Cork.

Joe was of medium height and build, and invariably well dressed; his face was markedly thin and sharp. He was remembered locally for his quiet, almost shy manner combined with a thoughtful intelligence and ready wit. He remained a 15practising Catholic, and at one stage was thought to have a vocation for the priesthood. Widely read, totally committed and clearly possessing leadership potential, he was the explosives expert for the London mission, under the assumed identity of John O’Brien.

Eddie Butler, one of four brothers from Castleconnell, a prized salmon-fishing haunt on the east bank of the Shannon, was the only one with a criminal record. As a youth, he had been caught daubing anti-British and pro-Republican graffiti on the roads near his home in County Limerick. He was never chased up to pay the fine. Butler settled down after that – there were bigger jobs to be done – and joined the Provisionals in 1972. He was tough and burly, the last man the IRA would expect to crack under police interrogation. He was, however, frightened of flying. Butler was the dependable back-up man, whose job would regularly entail providing covering fire with a Sten gun on the unit’s missions.

Hugh Doherty, born in Glasgow, was ostensibly the odd man out, but his Irish roots stood out as much as his red hair and beard. His family, like many others, had migrated from the Irish Republic to Scotland to look for work after the Second World War, but every year the Dohertys returned to Donegal for the summer holidays and Hugh eventually settled there with his elder brother. He was the altar boy who left school at 15, became an itinerant building-site labourer and then a Provo volunteer.

The acknowledged first boss of the unit was Brendan Dowd, an imposing six-footer. He was the nerveless leader-by-example. He was brought up the youngest of a family of seven brothers and seven sisters (six of whom died) in a smallholder’s cottage at Raheeny, near the riverside town of Tralee on the Dingle Peninsula. His father, a retired forestry 16worker, was a member of Sinn Féin, and his mother was equally committed.

En route to enlisting with the Provisionals, he became a crane driver and motor mechanic, a line of work that led him to travel frequently to England. His expertise with vehicles would later be adapted to serve an additional skill – stealing cars – but his principal job was to establish the London ASU and, once that was operating effectively, to set up further ASUs elsewhere on the mainland.

Dowd and O’Connell were the first to arrive, crossing from Shannon to Heathrow in early August 1974, ostensibly looking for work. Once in London, they headed for Fulham, where there were enough Irish residents not to make them conspicuous but not so many as to constitute an obvious community like that in Kilburn, where Irish gregariousness and police interest could put them at risk. They rented a twin bedsit flat at 21 Waldemar Avenue, close to Fulham Road, where they were joined by ‘English Joe’ Gilhooley, who had already been operating on the mainland since at least March. Selected as another member of Brian Keenan’s chosen team, Gilhooley, born in 1951 of Irish parents, had grown up in Moss Side, Manchester, settled in Dublin and adopted Irish citizenship.

The £10 weekly rent on the flat was paid with scrupulous punctuality. They were polite to the neighbours but never stopped to encourage conversations on the doorstep or in the hallway. They left and returned at regular hours, as if going to work. They were seen to be smartly but casually dressed. The first of a number of London safe houses was thus quietly established.

* in An Phoblacht, Republican News, 1 December 1988

2

On Active Service

‘The British Government and the British people must realise that because of the terrible war they wage in Ireland they will suffer the consequences.’

dáithí ó conaill, IRA Chief of Staff, ITV, 1974

The IRA rationale for bombing Britain is, of course, rooted in history that long pre-dates the formation of the IRA.

In 1867 a group of Fenians planted a bomb at Clerkenwell Prison in London in an unsuccessful attempt to spring a colleague. It killed 12 people and moved Ireland to the top of the British political agenda of the day, thus giving birth to the Republican notion that one bomb in Britain is worth 100 bombs in Belfast. Both the truth and the fallacy of the argument hold today. A bomb on ‘England’s sod’ has always commanded overwhelmingly greater press and public reaction than any explosion in Ireland, either north or south of 18the border. The corollary has also been vehement anti-Irish emotion, with stiff anti-terrorist legislation and a redoubled political will set against concessions in the face of violence.

Although the IRA has, at regular intervals, brought the war to Britain, in the late twentieth century this didn’t occur until well into the Troubles. In 1972 the Official IRA bombed the military garrison at Aldershot in a claimed reprisal for the Catholic deaths on Derry’s Bloody Sunday. The bomb killed a Roman Catholic chaplain, five cleaning women and a gardener – a catastrophic outcome which prompted the Officials to order a ceasefire for an indefinite period.

By now, the Provisional IRA had taken over the military side of the campaign, considering the Officials to have reneged on the true principles of 32-county Republicanism and to have failed to protect the Belfast Catholic ghettos against the waves of Protestant attacks in 1969. The split was formalised in 1970 and the Provisionals’ first mainland bombings followed in 1972 with the Price sisters’ car bombs in Whitehall and the Old Bailey.

In 1973 and 1974 a number of one-off attacks took place: 40 schoolchildren were injured and a woman killed by a blast at the Tower of London (the standing instruction to avoid ‘innocent’ victims was interpreted loosely throughout the history of the mainland campaigns).

Peter McMullen, who had deserted from the 1st Battalion of the British Army’s Parachute Regiment three days before Bloody Sunday, had meanwhile linked up with Joseph Gilhooley. On 25 March 1974, the two men walked through the front gates of Claro Barracks in Yorkshire, a base of the Royal Engineers, and planted a time bomb which injured a woman canteen worker. The following month, on 28 April, their flat in Bootle was raided by police, who discovered 19forensic links with the Claro Barracks bomb. Gilhooley’s fingerprints were identified in the flat, together with a sketch-map of Bruneval Barracks in Aldershot, almost certainly drawn by McMullen. This information was duly passed to Hampshire Police and the relevant military authorities in Aldershot in June – four months before the Guildford bombings. Somewhat surprisingly, it was decided not to raise the alert state from ‘Bikini Black’ in Aldershot or the surrounding military establishments.* The men themselves had melted away, but in August Gilhooley resurfaced in London at the heart of the ASU.

These bombings coincided with a spate of mainland letter-bomb attacks, involving another man whom Keenan would attach to the London ASU – William (Liam) Joseph Quinn. Quinn had been born and brought up in the Irish American district of Sunset in San Francisco – an American citizen. But by 1970 what he saw on television news from Belfast spurred him into active Republicanism. In 1971 he quit his job with the US Mail and left for Ireland: the letter bombs of 1974 were his induction into active service for the Provisional IRA. Quinn’s fingerprints were on devices sent to three of the numerous ‘establishment’ British mainland targets.

Frightening as the flurry of letter-bomb attacks was, it was the M62 coach bomb that proved that the Provisionals were now able to place highly proficient bombers in England. During the 1974 general-election campaign, reconnaissance 20had established from where and when troop-carrying coaches left a Manchester bus depot for Catterick Camp in Yorkshire. As the soldiers’ belongings were loaded into the luggage hold, a time bomb was slipped in alongside. High on the Pennines between Huddersfield and Bradford it ripped the coach apart, killing two children, their mother and nine soldiers. The two main perpetrators got away and have never been caught. Judith Ward, a flatmate in their safe house, was sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment for her role in the attack. She was to serve 18 years before being released in 1992, following a unanimous ruling by the Court of Appeal that her conviction was ‘a grave miscarriage of justice’.

All this was a grim foretaste of the campaign to be waged by the new ASU now settling in to Fulham. Brendan Dowd, the leader, and Joe O’Connell, the explosives expert, began to list their targets, make their first discreet recces and assemble their lethal equipment.

From the beginning it was apparent that they intended to bomb and shoot their way through as much of the British legal, political and military establishment as possible. They obtained the Army List, the Civil Service Year Book, Who’s Who, Whitaker’s Almanack and lists of senior policemen, stipendiary magistrates and high sheriffs.

Potential targets in London ranged from the luxury department store Fortnum & Mason, Cartier, Harley Street and various streets in Knightsbridge to the International Telephone Exchange, a major telex exchange for City dealers, Walthamstow reservoir and Hackney Downs pumping station. O’Connell made a sketch plan of the environs of New Scotland Yard.

They accumulated railway timetables, a set of Liverpool and London telephone directories, stolen from post offices and 21libraries, and enough maps to fill a British Airways holdall: street maps of London, Liverpool, Bristol and Bath and the Medway towns, and bigger motoring atlases of Great Britain. Their reading matter was often austere: Freedom: The Wolfe Tone Way, Technology of Repression: Lessons from Ireland and The Anarchist’s Cook Book, which did at least promise in its foreword to provide a witty guide to bomb manufacture.

Harry Duggan, the youngest, and Eddie Butler, perhaps the toughest, arrived on 10 October 1974 to take a second bedsit on the top floor of the same Waldemar Avenue house. Social life was necessarily spartan. The team drank occasionally and sparingly at the Durrell Arms round the corner in Fulham Road. Hugh Doherty, who arrived in late 1974, joined an Irish social club in Camden Town – a dangerous move by the unit’s rigorous standards. The only evidence of incipient sexuality was Harry Duggan’s visit to a Soho strip club (enabling him to confirm to his colleagues that the management did not search the clientele) and a spoof reply to a Time Out lonely-hearts advertisement, filled out by the rest on behalf of Doherty but never posted.

The female couriers began their runs from Dublin, once every two months, usually carrying fresh targeting suggestions and £1,000 in cash for living expenses. The route used for guns, ammunition and explosives is less clear. In 1974 the Provisionals had supporters installed in ferries and airlines and among baggage-handling staff at points of entry to Britain. There were stories of explosives being smuggled in the door panels of cars, but the most common method was still by fishing boat, with secret landings on the Lancashire coast, or in containers through the port of Liverpool. In Fulham, the gelignite was wrapped in sawdust and wood shavings, placed in suitcases or under floorboards, and intermittently turned 22to prevent ‘weeping’ and the onset of ‘NG head’, the searing headache caused by proximity to exposed nitroglycerine.

The unit also did their own shopping. Coach bolts for inclusion in anti-personnel shrapnel bombs were picked up at hardware stores. For use in delayed-detonation devices – time bombs – Smith’s pocket watches were bought in quantity at branches of Comet and Woolworth. Thus equipped, the unit chose its first target.

* Army security section report dated 7 June 1974. (Had the alert state been raised, it is possible security measures would have been introduced in and around Aldershot, which might have made it more difficult for the IRA to penetrate the military pubs in the vicinity of Aldershot and nearby Guildford.)

3

Preparations for a Bombing

‘I was in charge of the operation.’

brendan dowd, 26 October 1976

The car was a Ford Escort. Dowd signed his name clearly: ‘Martin Moffitt’. The woman from the rental agency, Swan National, checked his driving licence and added the time and date: 17.30, 21 September 1974. She signed her own name, ‘Liz’, with a small circle over the ‘i’. Dowd needed no instruction about the car; he was used to Escorts. He swung out into the Saturday traffic and headed west from Victoria back to Fulham. It would be useful for Joe O’Connell to come on the recce to Guildford tonight with him and the other guy. Joe was good, but inexperienced in England, having arrived from Dublin only a month before. They would all three go, Dowd decided; two bombs, two pubs – one to enter each and Joe to observe.

They had been given the names of several suitable pubs in Guildford. The first, the Star, had no soldiers and they left at once. The Seven Stars was better. Then, finding themselves 24in North Street, they spotted the Horse & Groom. Glancing around from the doorway, Dowd took in a collection of tables set in alcoves to the left and a bar to the right, a jukebox, dim lighting. The place was already crowded with soldiers. The three stood near the bar and had a drink. Dowd made a mental note that it would be necessary to arrive here early to ensure getting a seat. They would have to do another recce on a quieter night. Dowd was a meticulous planner.

Returning to the Seven Stars, they found that the disco was now packed with people. Most of them were soldiers; it was the haircuts that gave them away. Again, the three Irishmen stood at the bar and watched the drinkers and the dancers. These were the right pubs, military pubs, Dowd thought. There would be no warning.

At 2.30 p.m. on Friday 4 October, ‘Martin Moffitt’ presented himself once more at the Swan National office next to Victoria Coach Station. This time he hired a white Hillman Avenger, RAE 211M, arranging to keep it over the weekend, though in the event he retained it for almost a week.

The bombs were made at the flat in Waldemar Avenue, Fulham, the next morning; there were six pounds of explosive – 12 sticks of gelignite, Frangex – in each. Dowd and O’Connell made the two bombs. The third man made the timers, using Smith’s Combat pocket watches. O’Connell explained later how this was done: first he removed the glass of the watch and snipped off the second hand, leaving nothing but a stump. At the ten o’clock position he stuck a piece of tape onto the glass of the watch and made a hole towards the centre so that the hour hand would pass underneath it, across the hole. Then he replaced the glass onto the watch mechanism. Removing an inch of plastic coating from a piece of wire, he doubled the end back and inserted it through the 25hole he had made in the glass and taped it in place. The other end of the wire was connected to a four-and-a-half-volt bell battery with two terminals, via an electrical detonator which was inserted into the centre of the sticks of gelignite. As the hour hand touched the wire, the circuit would be completed and the bomb would explode.*

In the late afternoon, the team was ready to set out. The bombs were to be carried into the pubs by two young women who now arrived from north London. Each carried two bags of similar design: one bag to convey the bomb into the pub, while the other, hidden under her coat, would be produced afterwards so that she appeared to carry out what she had brought in. They were handbags, about 12 inches long and seven inches deep; one pair were imitation-leather shoulder bags with a flap and a fastener (one brown, the other black); the second pair were identical to each other, dark cloth with wooden handles which closed together. The five young people climbed into the Avenger and headed south for the A3. Dowd, as usual, was driving. He had dressed unobtrusively, in a grey-flecked sports jacket and black trousers, and was clean-shaven, with his dark hair cut fairly short. He was to forget what the women were wearing; the important thing was not to attract attention.

In Guildford, he parked the car in a multi-storey car park tucked into a hollow behind the shops and flanked on one side by a cliff. It was not yet dusk when they arrived, though rain clouds reflected a fading, greyish light over the city. They sat in the car park, set the wire of the timer to the battery and the detonator. The bombs were placed into the two handbags with the battery and the watch packed on top.

26They discussed who should enter which pub. Dowd sent O’Connell with one of the women and the third man into the Seven Stars; then he and the second woman set out for the Horse & Groom.

It was still early when they entered the bar. Dowd was pleased with his timing: the Irish couple could mingle unobserved with the gathering crowd, but there were still empty seats in the dim recesses of the bar. Dowd ordered lager. They sat on a bench seat in an alcove with their backs against the gable-end wall, and surveyed their fellow customers. Many of them were Saturday-afternoon shoppers waiting for buses home, Dowd guessed; he had noted the bus stop outside the pub door. A few Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC) recruits started to arrive and, as time passed, an increasing number of young soldiers. Dowd’s choice was possibly more clever and more deadly than he knew. With the cheapest beer in town, the Horse & Groom was a favourite among young recruits from the Army bases at Pirbright and Aldershot. After an initial month confined to barracks, a Saturday night at the Horse & Groom or the Seven Stars disco was often the first taste of freedom for those servicemen and women, many of whom were no more than 17 years old.

The woman with Dowd slipped her handbag under the seat. They sat over it for long enough to have three drinks. There wasn’t a great deal to say. Witnesses saw them kiss each other; police were later to call them the ‘courting couple’. Dowd estimated their time in the pub at an hour or more.

O’Connell and the others were quicker. They had planned to leave their bomb under a table in the disco, but the only suitable table was occupied, so instead they found seats in a corner of the bar, to the left of the door as they went in. The woman put her bag on the floor and the man pushed it with his 27foot under the bench on which they were sitting. O’Connell noticed the barman watching them closely. Some Guardsmen came and sat beside them. One asked them a question about the time of buses to Aldershot.

After two drinks, the three left the pub and walked back to the car park. It was 15 minutes before Dowd and his companion reappeared, but they had allowed plenty of time. They reached Fulham, by O’Connell’s estimation, at about 8.15, and had a drink at the Durrell Arms. As the time drew towards nine o’clock, the hour they had set for the detonation of the Guildford time bombs, they left the pub. Dowd and O’Connell drove the women home. They switched on the car radio to listen for the news.

* Part of O’Connell’s description has deliberately been omitted here.

4

Explosion

‘You do appreciate that in the manufacture of devices there is something known as modus operandi; that you can see between devices which are made by the same man, subtle techniques of assembly which show up time after time …’

donald lidstone, forensic scientist, Old Bailey, February 1977

There was no warning.

The hour hand of the Smith’s Combat pocket watch approached 8.50 p.m. and touched the bare wire in the timing device. The nitroglycerine-based explosive erupted from the bag beneath the bench seat in an alcove of the Horse & Groom in Guildford.

It exploded with pulverising force. A phenomenon known as ‘gas wash’ hurled the tiniest particles – dust, grit, scraps of paper – from the point of detonation at a rate of two feet per millisecond to scour surrounding surfaces with the combined effects of a sandblaster and a shotgun.

29Those who heard it described the sound as a ‘dull thud’, a ‘large woomph’, a ‘buzzing’ and a ‘muffled roar’. There was a dazzling flash of blue light, then blackness as everyone in the pub was engulfed by a wave of intense heat.

A passing motorcyclist was blown off his machine. A woman police constable [WPC] in a nearby Panda car radioed, ‘Priority! Priority!’ Special Constable Malcolm Keith stumbled into the Horse & Groom. He shone his torch on to a pile of people bleeding in a hole in the floor. He swung one woman to safety and grabbed at someone’s leg. It came away in his hand and he let it go. He felt ‘stunned and sick’. The wooden floor was subsiding into the cellar.

Rob King, a reporter on the Surrey Daily Advertiser, who was working late in his office 100 yards away, ran to the pub: ‘On the corner I nearly stepped on the outstretched body of a young man,’ he wrote.

He was covered in blood and being helped by a couple who were shouting … When I got round the corner it was horrific. People were running, shouting and screaming. Many of them were young girls and many were clutching bleeding heads. There was blood everywhere. The entire front of the Horse & Groom was blown out – there was rubble everywhere, glass, bricks, timber. People were scrabbling among the debris trying to pull people out of the mess … Everyone seemed covered in blood. I couldn’t tell who were the injured and who were the rescuers …

Robert Burns had been sitting in the alcove with a family party celebrating his daughter Carol’s 19th birthday. Also in the party was Paul Craig, a plasterer from Hertfordshire, who 30was due to celebrate his 23rd birthday the following day. Paul and Carol had changed places just before 8.50 p.m.

There were five instantaneous deaths from the massive blast injuries: WRAC Private Caroline Jean Slater, 18, of Cannock, Staffordshire and WRAC Private Ann Ray Higgins Murray Hamilton, 19, of Crewe, who were both training at the Queen Elizabeth Barracks in Guildford; Guardsman William McKenzie Forsyth, 18, and Guardsman John Crawford Hunter, 17, boyhood friends from the same street in Barrhead, Renfrewshire, who had signed up with the Scots Guards three weeks earlier and were stationed at Pirbright; and civilian Paul Craig, the family friend who had swapped seats with Carol Burns seconds earlier.

The four young recruits had been sitting around a table in the alcove, two on stools and two on the bench seat. Caroline Slater had been sitting directly on top of the bomb. Particles of zinc from the battery of the timing mechanism were recovered from her body. Police photographs of the bodies do not bear description.

There were 57 injuries, major and minor. Those closest to the bomb suffered variously lost limbs, severe burns and cuts, fractures, burst eardrums and lifelong facial scarring. People were blown over the bar counter, thrown through windows and blasted out of the front door into the street.

From his hospital bed, Private Jimmy Cooper described the moment he came to. ‘I must have gone straight through the window because I was lying outside with my hair and clothes on fire. Some people tore off my jacket and shirt to save me from serious burns. My two mates were killed outright and another was critically injured.’

The front wall of the pub on North Street was all but blown out. This was actually fortunate, for if it had withstood 31the blast, much more of the explosive force would have been channelled back into the crowded bar and caused more casualties. As it was, the disintegrating floor absorbed much of the eruption. Had it not been for the recent insertion of steel supports into the brick pillars in the bar, the single-storey section of the building would probably have collapsed. Outside, shop windows up and down North Street were shattered.

The first 999 call from a member of the public was logged at Guildford Ambulance Depot at 8.50 p.m. A minute later the town’s emergency planning was activated by Police Headquarters Control and, in an impressive response, five ambulances and a fire engine were at the scene inside seven minutes. In all, 17 ambulances, including four military vehicles, were involved in the rescue operation. More doctors were summoned from a concert performance in the Civic Hall.

The disco in the Seven Stars was so loud that nobody heard the bomb go off at the Horse & Groom, but within a quarter of an hour, talk at the bar of an explosion at the pub round the corner prompted the Seven Stars’ manager, Owen O’Brien, to go and see for himself. His first reaction to the mass of police cars and ambulances was to give the order to his disc jockey Tim Cummin to shut down the disco. Then he took a second, closer look at the wreckage in North Street and hurried back to evacuate his pub. As fast as the 200 customers could be ushered out, Owen O’Brien and his bar staff searched the bars and toilets but found nothing. At 9.25, just after the last customer had left, a blast ripped the Seven Stars apart.

Mr O’Brien, his face and hands severely cut, staggered outside before losing consciousness. His wife Dorothy rescued their two young children, aged six and four, uninjured from an upstairs bedroom, along with the family’s pet poodle.

Remarkably, nobody was killed. Although the explosion 32had been as powerful as the one at the Horse & Groom, the wall nearest to the Seven Stars bomb and the concrete floor had both held up, and this had resulted in even greater internal wreckage. Had the evacuation not been ordered, the death toll at the Seven Stars might well have exceeded the five at the Horse & Groom. As it was, just eight people were injured. There was also wreckage in the narrow street outside. In a nearby pet shop the glass fish tanks shattered, leaving the goldfish to die on the shop floor.

The police now evacuated all other pubs in the town centre. Routes out of town were sealed off. Local military establishments were put on alert. A search was made of the grounds of Princess Anne’s then home at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst.

Throughout the night, blue flashing police lights lit up North Street and Swan Lane. Blood donors arrived at the Royal Surrey Hospital, where amputations and other emergency operations continued all night. By 8 a.m., as the rest of Britain woke up to Sunday-morning news of the latest IRA horror, the bodies of the dead were being taken to Chertsey mortuary.

Shock and outrage swept through the country and beyond. The Queen, the Prime Minister and the Pope sent messages of sympathy and condemnation. The Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, rescheduled his election campaigning to fly to Surrey. Many Conservative politicians were quick to call for the restoration of capital punishment, among them a former Solicitor General, who in later Conservative governments would rise to become Attorney General and Lord Chancellor, the brilliant criminal barrister and Queen’s Counsel Sir Michael Havers.

5

Womble Spaceman Invaders

‘It all seems so embarrassing to think that’s how we used to live then.’

carole richardson, HM Prison Styal, 1987

The occupants of 14 Linstead Street, London NW6 were rarely any trouble in the morning. By 11.30 on Saturday 5 October nobody was stirring in the Victorian terraced house. As usual, the old blanket that served as a curtain hung limply from a piece of string, partially blotting the daylight from the downstairs front room.

Linstead Street, just east of Kilburn High Road, was rundown and off the beaten track. There was little in the strongly Irish and Black quarter of Kilburn to attract property speculators in the 1970s: it was prime squatting territory.

Paddy Armstrong and Carole Richardson had the front room downstairs. Scattered round the rest of the house were Tom and Jacko Walker, Vintie, Patrick Rayne, Lenno, Pearce, John Brown and Maggie Carrass. Others came and went. There was a deranged kitten – not destined to live long since 34some wit had thought it clever to slip LSD into its food – and there was Leb, Carole’s recently adopted stray mongrel, part Labrador, part retriever, named after Lebanese Gold hashish. Kilburn was a predictable haunt for the young men, mostly Irish from Dublin and Belfast, who were now well away from parental restraints and thoroughly enjoying the big city. The girls were mostly local, equally glad to be off the leash and making up fast for what in many cases had been abusive and chaotic home lives.

The front room’s only furniture consisted of mattresses laid out side by side on the floor. There were no sheets. Inside three sleeping bags were Lisa Astin, 16, a regular visitor to the squat; her friend Carole Richardson, 17; and, curled beside her, Paddy Armstrong, Carole’s 24-year-old boyfriend from Belfast. Brian McLoughlin, who sometimes stayed in that room, had not come back last night. A few tattered pop posters adorned the walls but the main decoration was graffiti Lisa had daubed when she was stoned, the largest of which was a great beady eye, with the warning: ‘You Are Being Watched’. The most probable watchers would have been the local drug squad, but Big Brother had little to fear from the Linstead Street household. They might have been a nuisance to their neighbours, rolling home late at night and noisily drunk. But not even the most appalled would have marked them down as plausible enemies of the state.

Predictably, they had all got stoned again the night before, but for them it had been a comparatively mild evening as they settled for a regular haunt, the Windsor Castle on Harrow Road. Back at home after closing time, they gathered upstairs around Tom Walker’s record player. There was Pink Floyd, David Bowie and the current favourite, Eric Clapton’s 461 Ocean Boulevard. Everyone crashed out at around 2 a.m.

35Carole and Lisa were the first to emerge, shortly before midday. There was a semblance of routine in the household chores and Saturday – or every other Saturday – was launderette day. Fat chance that Paddy would volunteer to do the washing. His Saturdays were mapped out according to more traditional male imperatives: the pub and the bookie’s.

Carole was his first and only girlfriend in London. They had met briefly in a squat in West End Lane in July and had got together properly at Lisa’s birthday party on 6 September. Since then, they had slept with each other most nights, although they rarely spent their days together. Carole was attractive: she had long brown hair, usually centre-parted, with a touch of red in it, and a strong, handsome face, with clear, sometimes mischievous eyes, and she was about five feet seven inches tall. Paddy would never have let on, but he had tasted only a fraction of her experience with sex and drugs when he was 17.

Carole gathered up the dirty clothes as Paddy slept on. He was already getting chubby in the face and the gut. That was the beer. He certainly didn’t eat properly. He had immature sideburns and a long straggle of lank, fair hair which Carole thought he could wash more often. She looked on him fondly, as gentle and wise, a great soft thing. She called him Piggy: ‘Silly Piggy’. The relationship was one month old and they were already talking precipitately of marriage. She didn’t mind taking his clothes around the corner to the Hemstal Road launderette.

The laundry load was an hour’s worth of washing and tumble-drying, so while Lisa stayed to supervise, Carole would usually dash off to catch her mother at her regular Saturday hairdresser’s appointment on Cricklewood Broadway. She was close to her mother and took care to keep 36in touch, but relations with her stepfather, Alan Docherty, were downright impossible. It had all come to a head in July with a series of increasingly ugly rows about staying out all night. Carole had disappeared into a King’s Cross squat for a drug binge which lasted three nights. She still hadn’t returned to the family home in Iverson Road, West Hampstead when Docherty spotted her in Kilburn High Road.

There was a screaming, stand-up row; slaps were exchanged and there was a parting ultimatum from Docherty: ‘If you’re not home in five minutes, don’t bother coming back at all.’ Carole did return home, but only to pick up some clothes. This time she left for good.

Docherty was not strictly Carole’s stepfather in 1974, although that was what she called him. He had been living with her mother for four years, ever since they’d moved out of Carole’s maternal grandparents’ small flat in Dunster Gardens, Kilburn. As for Carole’s real father, she had never seen him and never knew his name.

Carole’s mother, Anne Richardson, was a meek soul who shrank from taking sides during the rows, and so mother and daughter now held unofficial meetings away from the house, at the hairdresser’s or at the Regent Street Polytechnic, where Anne had an office job. She despaired of her only daughter. The girl was running wild, out of control. Everything had gone so well until Carole was 13. Hadn’t they been perfectly happy living in Dunster Gardens with her grandparents? Grandpa was secretary of the Kilburn Evangelical Church, Grandma was the Sunday-school teacher and Carole used to go along every Sunday. She had seemed to like it.

Then they moved and Docherty had appeared on the scene. Carole started playing truant from Carlton Vale School for Girls. Someone from education welfare came round to see 37Mrs Richardson about it once, but it got no better when she transferred to Aylestone Middle School in Willesden.

Bunking off school meant long, aimless wanderings around London and an early grounding in shoplifting. It was on one of these expeditions that Carole, then 11, found herself in Hyde Park watching a group of horses and riders and trailed them back to Lilo Bloom’s Riding School in Grosvenor Crescent Mews, Belgravia. There was always room for willing girls to muck out, and soon Carole was allowed to ride out with the others, too. A long attachment to horses began, holding out the promise of eventual work and a place to live away from the deteriorating atmosphere at home.