9,60 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Daunt Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

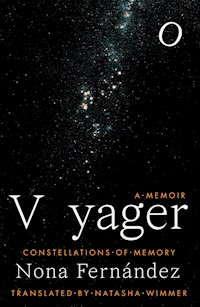

One of the world's foremost spots for astronomical observation, the Atacama Desert in Chile is also where, in October 1973, twenty-six people were executed by Pinochet's Caravan of Death. Decades on, a petition gathers for a constellation's stars to be dedicated to them. Nona Fernández is made a godmother to Mario Argüelles Toro, star HD89353, and asked to write a message to his family.When her own mother begins to suffer from fainting spells, Fernández accompanies her to neurological examinations. There, the mapping of her mother's brain activity – groups of neurons glowing and sparking on screen – calls to mind the night sky, as memories light up into a complex stellar tapestry.Weaving together the narrative of her mother's illness with stories of the cosmos and of her country, Fernández braids astronomy and astrology, neuroscience and memory, family history and national history into an intensely imagined autobiographical work.A profound reckoning with the past, Voyager is a refusal to allow lives to be forgotten and truths inconvenient to those in power erased. It confirms Nona Fernández as one of the great chroniclers of our time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 140

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

‘Nona demonstrates that the past – personal and political – needs a telescope as much as a microscope, to make out the disappearing ghosts of lost memories and people and ideals. Information from Chile’s recent history, as with the events of each individual life, can merge into the blackness between stars. Nona Fernández has the courage to go looking – the past isn’t always immediately visible, which doesn’t mean it isn’t there.’ Richard Beard, author of The Day That Went Missing

Praise for Space Invaders and The Twilight Zone

‘Fernández’s picturesque language and dream-like atmosphere is well worth being invaded by.’ Patti Smith

‘Wildly innovative, a major contribution to literature.’ New York Times Book Review

‘There is an incantatory quality … a feeling of walking, as though under a spell, and then accidentally tripping into the murky unknown.’ Paris Review

‘An absolute gem – a book of uncommon depth, precise in its language, unsparing in its emotion, unflinching as it evokes a past many would prefer to forget.’ Daniel Alarcón

VOYAGER

constellations of memory

Nona Fernández

translated by Natasha Wimmer

For Patricia the mother star

The Voyagers are two space probes launched by NASA in 1977. Multiple arms and antennae jut from them, making them look curiously like cosmic insects. Their sophisticated framework accommodates cameras, light sensors, sonic radar: an array of instruments for measuring and gauging temperature, colour, plasma waves, particle energy. The Voyagers are equipped to be two perfect huntresses. Their task is to record. To store fragments of stellar memory

We must bring new energy to remembering.

Make memory talk to the troubled present.

—Nelly Richard

While I live, I remember.

—Agnès Varda

Contents

Southern Cross

My mother has been fainting. Without warning, for no apparent reason, she falls and briefly disconnects. It might be a few minutes or only a few seconds, but when she comes to she can’t remember what’s happened. The moment is tucked away in some hidden corner of her brain. When her eyes open, she generally finds herself under the gaze of a series of strangers trying to help by fanning her or offering her water and tissues. These strangers tend to try to help her piece together the time lost from her memory. You leaned against the wall, you held your head, you vomited, you sat down on the ground, you closed your eyes, you collapsed. A chorus of voices offering up details of the blackout, enough for her to partially recover the scrap of life hidden 2in a parenthesis in her brain. It upsets my mother not to be able to remember what happened in these spatio-temporal lapses. Falling down in the middle of the street, collapsing in her seat on the bus or in line at the supermarket – these things are less troubling than the lost minutes of lucidity. The black holes that lurk in her everyday memories bother her more than the bruises she collects each time she faints.

I understand my mother. I have a theory that we’re made up of these everyday memories. It’s not an original idea, but I believe it. The way we wake up, what we have for breakfast, a walk down the street, an unexpected downpour, some annoyance, a surprise in the middle of the day, a story in the paper, a phone call, a song on the radio, the preparation of a meal, the smell from the pot, a complaint filed, a scream heard. Each day and each night lived, year after year, with its full complement of activity and inactivity, upheavals and routines – continuous storing of all this is what translates into personal history. Our archive of memories is the closest thing we have to a record of identity. It’s the only clue to ourselves, the only way to figure ourselves out. I guess that’s why we’re asked to claim it on the therapist’s couch. Sorting through childhood, adolescence, youth; declaring step by step what we’ve lived. Because all of it – everything collected in the kaleidoscope of our hypothalamus – speaks for us. Describes and reveals us. Disjointed fragments, a pile of mirror shards, a heap of the past. The accumulation is what we’re made of.3

I understand my mother. Losing a memory is like losing a hand, an ear, one’s very navel.

On the hospital room monitor I can see my mother’s brain activity. She is lying on a bed, her head sprouting electrodes and her eyes tightly closed. A series of stimuli administered by the doctor triggers electric charges in her brain. A network of hundreds of thousands of neurons interwoven with millions of axons and dendrites exchanging messages via a connective system of multiple transmitters: that’s presumably what I’m seeing translated on the screen. The complexity of what’s going on in there when my mother inhales, exhales, or is illuminated by the soft flickering of a light on her eyelids is indescribable. And when the doctor suggests a simple relaxation exercise, like thinking of a happy moment in her life, her brain really puts on a show. As my mother conjures some unspoken memory, a group of neurons lights up. In his office, the doctor showed us images of active neurons. Though the picture on the monitor doesn’t translate those electric sparks the same way, what I see looks like a starscape. An imaginary chorus of stars twinkling softly in my mother’s brain, soothing her, steadying her nerves during this test. A network stitching together familiar and comforting sensory details, I guess. Smells, tastes, colours, textures, temperatures, emotions. A neuronal circuit like the most complex stellar tapestry. 4In my mother’s brain, groups of stars constellate in the name of the fond memory lighting them up.

The last time I saw a constellation with any clarity was years ago, up north, far from the polluted skies of Santiago. I spotted Ursa Minor, Orion, the Three Marys, and the Southern Cross, which as a child I was told pointed the way home. I summon the memory and I think about the spectacle surely being staged inside my head.

A moonless night. The cold of the Atacama Desert creeping up the sleeves of my jacket. Some drowsiness, pent-up fatigue. Soreness in my neck from long minutes of gazing skyward. An astronomer indicating different constellations with a laser pointer, explaining to a group of tourists and me that all those distant lights we see shining above our heads come from the past. Depending how far away they are, we might be talking about billions of years. The glow from stars that may be dead or gone. Reports of their death have yet to reach us and what we see is the glimmer of a life possibly extinguished without our knowing it. Shafts of light freezing the past in our gaze, like family snapshots in a photograph album or the kaleidoscopic patterns of our own memory.

As we stare open-mouthed at the firmament, immersed in our genuinely Palaeolithic ritual, I remember a crazy theory my mother came up with when I was little. I think it 5was at our Barrancas house in the port city of San Antonio, near the sea, another place you could see the stars. Sitting on the patio, smoking a cigarette on a summer night, my mother said that way up there in the night sky little people were trying to send messages with mirrors. A kind of luminous Morse code, relayed in flashes. I can’t remember why she said it. She probably came up with it in response to some question of mine. What I do remember is that I assumed the messages sent by those little people in the sky were to say hello and assure us they were there, despite the distance and the darkness. Hello, here we are, the little people, don’t forget us. They never stopped signalling. We couldn’t see them during the day, but they were always there. Whether or not we looked up, whether or not we were inside our houses in the city, under a blanket of pollution, blinded by neon lights and billboards, oblivious of what was happening above, the little people’s signals were there and would be there every night of our lives, flashing for us. Lights from the past making a home in our present, lighting up the fearsome darkness like a beacon.

Crazy as her old theory might be, a vague sense of peace came over me when I remembered it on that cold night in the desert. Like a whisper, like the soft voices of grandmothers singing us to sleep, like the memory my mother summoned in the examination room to try to soothe herself. A buried urge for a return to the womb satisfied by that nocturnal scene. The strange sense of an 6enduring, mysterious, protective reality, confirmed by each of those orbs speaking to me with their light from another time. Hello, here we are, don’t forget us.

In a life I never had I was a brave cosmonaut and I navigated the stars I’d always watched curiously. In this life I plunged into strange galaxies, witnessed the explosion of supernovas, escaped from black holes, and crossed entire nebulae; I was surprised by the dance of comets, the streaking passage of tens of meteorites, the presence of white dwarfs and red giants. I saw hundreds of stars as yet unnamed twinkling around me; I yearned to hear their dead voices, heed their cries for help. And from each stage of this voyage I never made, I sent postcards of the starscapes that sprang to life in my mind when I saw a memory of my mother’s on the monitor in that hospital room.

As I learnt in the desert, light from the past illuminates our present. My mother summons a happy scene from her life and the neuronal mechanism is a present act that reverberates electrically in the shape of a constellation. My mother revives a scene from her past, and the brain process is a present act as complex as the vast fabric of the cosmos that knits itself mysteriously over our heads, enthralling and confounding us. Wrong though I may be, I like to think that the human brain – the organ used by women and men for centuries to observe the universe and try to 7understand it – must be one of the most complex systems in the universe.

Inside my mother’s brain, stars constellate under the name of the fond memory that lights them up.

But what memory is it?

What piece of her broken mirror are we talking about?

Epilepsy, that’s what’s causing my mother’s disconnects. After this test and the many others that preceded it, the neurologist gives us his final diagnosis. The fits are triggered by an excess of electrical activity in one of her neuronal circuits. I imagine something like an energy drain, a cerebral short, a momentary blackout, a halt in transmissions for the duration of one of her episodes. Then brain activity is restored and my mother starts working again. Same as a house when the main fuse blows and everything stops. Clocks, televisions, radios, refrigerators, the internet, a world on pause, still and silent until someone flips the right switch and the house alarm goes off and the system resets and everything starts up again. As if the short circuit hadn’t frozen anything. As if a moment of life – a hand, an ear, even the navel – hadn’t been lost in that space-time parenthesis.

We exit the neurologist’s office and I look at my mother with new eyes. Now I know that she’s carrying the whole 8cosmos on her shoulders. I tell her what I saw on the doctor’s screen. I tell her how much her brain looks like the night sky. I tell her about the electrical patterns of her neurons, the glow of her memory, the constellation that lit up the moment she summoned it, the luminescent reflection of her own past. I ask which happy scene it was that I saw twinkling on the monitor in the doctor’s office and she smiles and says she was remembering the moment I was born.

My life’s first scene is a constellation in my mother’s brain.

(Hello, we’re the little people.)

The ground zero of my past shining in her head.

(Here we are, don’t forget us.)

The Southern Cross showing me the way home.

www.constelaciondeloscaidos.cl

A few months ago I was invited to sign a petition addressed to the International Astronomical Union. My signature, along with those of anyone else interested, would endorse the creation of a new constellation in the sky. The explanation included a link to an Amnesty International web page, where more information could be found: www.constelaciondeloscaidos.cl.1

Atacama Desert, Chile. The best place in the world for stargazing. The same place where, forty-five years ago, 10twenty-six Chileans were executed by the Caravan of Death. This is what I read on the screen as a video begins to play. How do we make sure the twenty-six are never forgotten? How do we make sure such things never happen again? Now images appear before my eyes of the desert, the night sky, an aerial shot of the city of Calama, where the victims were from. Next comes an array of black-and-white photographs of their faces. We want to rename twenty-six stars and give them the names of the victims, I read on the screen. We plan to create the first memorial in the universe where stories and lives can be told in the stars. Next we see the wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters of the victims, sifting the desert in search of some trace of the dead they were never able to bury. The same sky that one day watched them depart today remembers them forever, I read. Learn about the constellation and add your signature to send the petition to the International Astronomical Union.

1. The website www.constelaciondeloscaidos.cl no longer exists. It’s a dead star whose light has yet to reach us. Some traces of this project can be found here: https://amnistia.cl/noticia/chile-dia-internacional-de-apoyo-a-las-victimas-de-la-tortura-constelacion-de-los-caidos/

Cancer

I was born when the sun was crossing the constellation of Cancer at noon on a winter day in 1971. Early that morning my mother felt a hot liquid run between her legs and assumed it was her water breaking. It was her first and only labour. She had a suitcase ready to go and she left the house carrying it and a towel to wipe herself off. A few yards away on the same street was a garage where Don Tito came early each morning to work in grease-stained overalls. My mother asked him to help her, please. Her body was telling her it was time to have the baby, but she couldn’t take a bus or get to the clinic by herself. So Don Tito, with his grimy hands and ginger moustache, got into one of the junkers in the shop and set off as fast as he could with my mother, her suitcase, and her towel. 12

There are more than one hundred stars in the constellation of Cancer, only fifty of them visible. The brightest of all is Al Tarf, an orange giant five hundred times brighter than the sun and 290 light years from our solar system. My brain can’t fathom exactly what that means, but I understand that its light departed a long, long time ago, making an endless voyage from the past to twinkle here over my head. What I see in the night sky, when I can see anything at all, is a bright postcard of a moment that has ceased to exist but lives on in the glow. Like my mother’s memory of the moment I was born.