Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

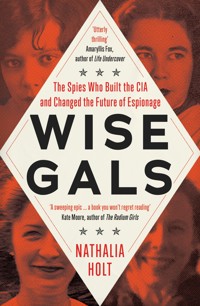

A TIMES BEST PAPERBACK OF THE YEAR 2023 AS HEARD ON BBC RADIO 4 BOOK OF THE WEEK 'A necessary corrective to the sexism and misogyny rife in spy tales ... contains some eye-opening tales of espionage' GUARDIAN 'Gripping' FINANCIAL TIMES 'A thrilling book, as propulsive as classic le Carré' THE TIMES 'As much le Carré as it is Hidden Figures.' AMARYLLIS FOX, author of Life Undercover The never-before-told story of a small cadre of influential female spies in the precarious early days of the CIA - women who helped create the template for cutting-edge espionage (and blazed new paths for equality in the workplace). In the wake of World War II, four agents were critical in helping build a new organisation now known as the CIA. Adelaide Hawkins, Mary Hutchison, Eloise Page, and Elizabeth Sudmeier, called the 'wise gals' by their male colleagues because of their sharp sense of humour and even quicker intelligence, were not the stereotypical femme fatale of spy novels. They were smart, courageous, and groundbreaking agents at the top of their class, instrumental in both developing innovative tools for intelligence gathering - and insisting (in their own unique ways) that they receive the credit and pay their expertise deserved. Adelaide rose through the ranks, developing new cryptosystems that advanced how spies communicate with each other. Mary worked overseas in Europe and Asia, building partnerships and allegiances that would last decades. Elizabeth would risk her life in the Middle East in order to gain intelligence on deadly Soviet weaponry. Eloise would wield influence on scientific and technical operations worldwide, ultimately exposing global terrorism threats. Meticulously researched and beautifully told, Holt uses firsthand interviews with past and present officials and declassified government documents to uncover the stories of these four inspirational women. Wise Gals sheds a light on the untold history of the women whose daring foreign intrigues, domestic persistence, and fighting spirit have been and continue to be instrumental to the world's security.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 559

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY NATHALIA HOLT

The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History

Rise of the Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled Us, from Missiles to the Moon to Mars

Cured: The People Who Defeated HIV

First published in the UK in 2023

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

First published in the USA in 2022

by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Published by arrangement with G.P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Grantham Book Services, Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa

by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

ISBN: 978-178578-958-8e-BOOK ISBN: 978-178578-959-5

Text copyright © 2022 Nathalia Holt

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Interior art: World map © Oleksandr Molotkovych/Shutterstock.com

Book design by Kristin del Rosario

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

For the women who toil, invisible, invaluable, for Laurie

Put yourself behind my eyes

and see me as I see myself,

for I have chosen to dwell in a place you cannot see.

—JALĀL AL-DĪN MUḤAMMAD RŪMĪ

CONTENTS

AUTHOR’S NOTE

November 1953

PART I

“ISN’T THAT A STRANGE PROFESSION?”

1.Jessica, 1934–1944

2.Safehaven, 1944–1945

3.Werwolf, 1945

PART II

“UNSAVORY ACTS”

4.Rusty, 1946

5.Belladonna, 1946

6.Trident, 1947

7.Opera, 1947–1948

PART III

“SHE GETS INTO YOUR DREAMS”

8.Vermont, 1949

9.Kubark, 1950

10.Loss, 1951

11.Aquatone, 1952

12.Petticoat, 1953

PART IV

“FUMBLING IN THE DARK”

13.Farmer, 1954

14.Musketeer, 1956

15.NSG5520, 1957

16.Bluebat, 1958

17.Aerodynamic, 1959

PART V

“THE WORK OF A MAN”

18.Mudlark, 1960

19.Lincoln, 1961

20.Psalm, 1962

21.Hydra, 1965–1972

Epilogue: State Secrets

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The Wise Gals are no longer with us to tell their stories, and yet they still speak. This work of nonfiction was researched thanks to the materials they left behind, which include diaries, letters, interviews, reports, memos, scrapbooks, and photographs. In addition to these sources, the Central Intelligence Agency has released primary documents about the careers of these women and the challenges they faced. All the work published in this book is declassified and was obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

A large portion of this book is credited to the CIA officers, both retired and active, who contributed their stories and memories. Just like the work these men and women perform, their contributions to the book remain anonymous. For this reason, their names appear as redacted in the source notes, and their own stories, while worthy of telling, have mostly been left out.

Firsthand accounts of historical events are often slanted by those who have lived through them. To limit this, I have used material from archival sources, acquired from multiple countries, to ensure that the material I obtained through these interviews is factual. Occasionally, material obtained from an interview was unable to be supported through outside sources. In these instances, I’ve weighed other evidence, and carefully checked dates and timing, when deciding whether to include these portions within the book. When I’ve chosen to include these firsthand histories without supporting documentation, I’ve noted the instance in the endnotes.

The thoughts and feelings of individuals in the book were obtained through their personal materials and author interviews with those who knew them. All quoted material is obtained directly from primary sources and credited in the endnotes.

This is the kind of book the Wise Gals could not have anticipated would ever be written. In their later years, they watched as their male colleagues became the subjects of multiple biographies, while their lives and accomplishments remained undocumented. Sadly, their stories could not have been told while the women were still with us. If living, neither the identities of the women, nor their work within the agency, would have been disclosed by the CIA. It is only in death that the full measure of their accomplishments can be revealed.

WISE GALS

NOVEMBER 1953

A small group of women gathered together just a few blocks from the White House to contemplate the dismal future of American intelligence. They had spent the past decade forming the fledgling American espionage enterprise known as the Central Intelligence Agency, breaking new ground for women in the workplace by working alongside men in dangerous, important operations. They’d played an integral part in gathering the intelligence that had won World War II for the Allies, and now they were on the front lines of the Cold War, spreading their network of spies across the world. But at this moment, these female founders were taking a rare opportunity to look inward.

And what they saw made them angry.

Eloise Page wasn’t the kind of woman who was prone to emotional outbursts. Her friends would tell you that when she was upset, her demeanor was usually icy rather than explosive. She had a firm sense of right and wrong, and she never hesitated to reprimand those who crossed a line. Yet on this unusually balmy day in Washington, D.C., her temper was fiery.

For the past few months, Eloise and a group of twenty-two of her female colleagues at the CIA had tackled a seemingly impossible goal: to strip away the inherent sexism that plagued the institution they loved. Women were doing the same work as their male counterparts, Eloise and her colleagues argued, but they weren’t getting the same pay or recognition as the men they worked alongside each day. That had to change. To accomplish this, they had carefully documented the experiences of women at the agency over the course of years. The daring missions. The enormous responsibility. These women had given everything to safeguard America’s security. In fact, some of their colleagues had even given their lives.

Eloise and the other women knew that achieving their aim of equal pay and recognition for their work would not be easy. They met in the evenings, after their regular workday was over, gathering statistics and stories that would prove their case to the higher-ups at the CIA. While the group was officially named the Committee on Professional Women, everyone at the agency jokingly called them the Petticoat Panel. It became a nickname they loathed but adopted nevertheless, as a reminder of exactly what they were up against.

For Eloise, who had spent years overseas working in complex CIA operations, the task before them was rather mundane. They compiled numbers from each department of the agency, took into account the education and work experience of every employee, combined the dry statistics with personal anecdotes, and then prepared their reports. Yet their training in covert operations was aiding their progress in ways their male managers could not have predicted. As they interviewed female employees, they peeled off the niceties that people naturally coated their experiences in and exposed what a career in government service truly looked like if you were a woman.

What they found wasn’t pretty.

Repeatedly they heard frustration in their colleagues’ voices. The number one reason that women were leaving the CIA was not marriage or pregnancy, as so many executives claimed. Instead, their interviews revealed a deep dissatisfaction among women, specifically concerning their promotion within the agency. Although 40 percent of the CIA’s workforce in 1952 was made up of women, only 20 percent had reached a mid-range salary level (about $7,514 a year). This was compared with 70 percent of their male colleagues who were paid at that level.

The problem wasn’t that the women weren’t being given responsibility, either; it was that they weren’t being paid for it. Many female employees had advanced degrees and were directing the activities of large teams. They had worked on successful operations and had years of experience in the field. In many cases, they even had the support of male colleagues and the recommendations of their bosses.

Yet they couldn’t get a raise.

As she looked around the room, Eloise realized that she had never worked so closely with a group of women before. No matter whether she was in London, Brussels, Paris, or Washington, D.C., it seemed she was always in a room of men. Nor had she ever known her fellow CIA officers so well. After all, they were (by nature and by profession) a secretive bunch, often scattered around the world in various sensitive locales. But the Petticoat Panel was a chance for her and the other women in the CIA to meet and open up to one another in a way they weren’t usually able to when on the job. While delving into the experiences of the women of their agency, it was only natural for them to share their own backgrounds. When one of her colleagues asked Eloise how she’d managed to secure a promotion from secretary to officer from General William Donovan, the father of American intelligence, after the war, she responded, “Oh, I had the goods on Donovan,” a wicked smile on her lips.

Everyone loved the lively Elizabeth Sudmeier, whom they called Liz. She had grown up on a reservation in South Dakota and liked to tease her friends in the Lakota Sioux language. She had recently completed Junior Officer Training, also called JOT, and was the only woman in her class, so she could report directly on gender discrepancies in CIA instruction and mentoring. “Women in the JOT program need to be more highly qualified than most of the men,” she said.

Then there was Mary Hutchison, a woman who had first been dismissed by the agency as a “contract wife.” The term referred to a woman married to a CIA officer, who was assumed to be trained and employed by the agency merely because of her marriage. Such roles were often entry points for women into the CIA, but Mary—with her proficiency in several languages, her doctorate in archaeology, and her string of fiery comebacks—was uniquely suited for a career in espionage. If only she could get the higher-ups at the CIA to notice her exemplary work.

Eloise had grown closest to the chairwoman of their group, Adelaide Hawkins, whom she called Addy. They were the same age, they both hailed from small towns in the South, and they each had joined the CIA during World War II, before it even officially existed (when it had gone by the moniker OSS, or Office of Strategic Services). Friendly as they were, Eloise sensed Addy’s envy of her overseas assignments. While Eloise had spent years in Europe, Addy, a divorced mom with three children, had been bound stateside. It didn’t matter that Addy’s children were grown, that fathers were allowed to work overseas, or even that she was highly qualified for such positions. Addy was a mother, so she would never be sent overseas; that was that. Annoyed by the inconsistency of the agency, Addy hoped that her work with the Petticoat Panel might spur an overseas assignment for herself.

There were dangers overseas. A few members of the panel knew about another woman, one who wasn’t there that day. Jane Burrell was the model of a tough, successful CIA officer. Working across France and Germany, Jane had wrestled with difficult double agents, charmed deadly assassins, and sent dozens of Nazis to their doom.

With Jane’s example to lead the way, how could the Petticoat Panel not succeed? They had a cadre of smart women who had picked this moment, in 1953, to transform the intelligence agency they had built a decade earlier. It wasn’t just their colleagues who were counting on them; it was the CIA itself. Talented women were leaving the agency, and each dissatisfied officer was fragmenting the future of American espionage.

The panel represented both their opportunity and their legacy, and the senior male administrators felt the crushing pressure of their historic expectations. The stakes were high, and their opponent was unrelenting. “I think it is important to remember how it came into being,” said one of the men, referring to the Petticoat Panel, “because [of] a couple of wise gals.”

PART I

“ISN’T THAT A STRANGE PROFESSION?”

CHAPTER ONE

JESSICA

1934–1944

The message could kill someone. It moved from Berlin to Lisbon to Normandy. Then it was stolen off the coast and sent to Bletchley. Twisted around until nearly unrecognizable, it was shipped off to America. In Washington, D.C., it was jumbled once more before being sent to London and then back to France. The paper swam in a sea of secret messages that formed a flood of intelligence during World War II. Finally, in Normandy, on December 20, 1943, X-2 counterintelligence agent Jane Burrell caught it and read the name that had been hidden between the mixed-up letters.

The name: Carl Eitel.

Carl Eitel had other names. Ten years earlier, when he worked as a waiter on the SS Bremen, moving between Germany and New York, he had been known as Charles Rene Gross. The waiter had spent long hours detailing the ports of New York in his notebook, with an emphasis on their fortifications and aircraft support. Once in the city, he slipped off to the Roxy cinema and then got a beer at Café Vaterland on the corner of Eighty-Sixth Street and Second Avenue. Relaxed and happy, he casually wandered the streets, stopping at every bookstall he could find. He didn’t look for reading material. Instead, he purchased technical magazines by the dozen. No matter the subject, Eitel wanted them. Although his behavior had been unusual, he’d passed unnoticed at the time. It was 1934, after all, and the borders of America were then wide open for Western Europeans . . . even those with an odd penchant for technical detail.

In his hotel in New York, Eitel took a tube of what looked like modeling clay, working it through his fingers until the material was soft and supple. Squeezing a little into a glass partially filled with water, he stirred the substance until it turned a mustardy yellow color. He dipped a toothpick into the thick liquid and dragged it across a sheet of rough paper, writing sentences that quickly faded as the fluid dried on the page. The rugged bond obscured any imperfections caused by writing with a crude toothpick, and soon the sheet of paper appeared blank again. Eitel then used that same piece of seemingly blank paper to write an innocuous letter to Germany, sharing mundane details of life in Manhattan and how much he missed his homeland. But underneath these pleasantries, the contents of his missive were anything but harmless.

Eitel was in fact working for Abwehr, the German intelligence agency, scouting details about the technological capabilities of the country his homeland would soon be at war with. Of all his various duties in the US in that precarious inter-war period, however, none was more important than recruiting new agents. Earlier in 1934, he had introduced a young Spaniard named Juan Frutos to the world of German espionage. Frutos was at the time a baggage handler who also worked on the SS Bremen. An ocean liner was a wonderful place for a spy like Eitel to enlist new agents: it was full of young people who spoke multiple languages, were accustomed to travel, and were in need of money. Frutos was enthusiastic about working for Eitel, no matter how seemingly inconsequential the mission. On one trip he had extravagantly handed Eitel an envelope, as proud as if it contained Winston Churchill’s darkest secrets. Instead it was packed with the modest request made by Eitel: dozens of postcards, each one depicting a different French warship. Simple, yes—but these sorts of details would inform crucial intelligence for the years and conflicts that followed.

The two men had kept in contact over the years, as Eitel moved from New York to Germany and then on to Brest, France. The location had the strategic advantage as the closest French port city to the Americas. There Eitel’s life had become increasingly luxurious, as World War II had begun and Eitel enjoyed the fruits of his years of intelligence work. During the day he worked inside the charming surroundings of an ancient stone castle, the Château de Brest, which was seized during Germany’s occupation of France. He was building an intelligence service using the port’s fishing boats. Every day was profitable: even if the boats didn’t turn up information about the suspicious travel habits of French citizens, the daily catch made a healthy addition to his bank balance.

His hair had started thinning and his potbelly ballooned, but Eitel was happy. In the evenings he took his girlfriend, Marie Cann, to the bistro he purchased from the profits of Abwehr and the fish market. The rest of his money he blew on extravagant gold jewelry, not for Cann but for himself. His small, round glasses often reflected the glinting light from his gold chains and rings.

The good life was about to end for Eitel. In the summer of 1943, he left France for Lisbon, pulling behind him a web of intelligence agents that stretched across Germany, France, and now Portugal. In his pockets were papers that identified him as a French citizen named Charles Grey. If arrested, he would show those papers to the authorities and pledge his allegiance to the Allies. Yet hidden deep in his belongings, where he hoped they would never be found, were a German passport, a gun, and a vial of cyanide.

Carl Eitel.

Credit: The National Archives of the United Kingdom

The message that would lead to Eitel’s downfall seemed harmless at first glance. It was only a few lines long and was one of thousands of transmissions moving through Bletchley Park, Britain’s premier cryptanalysis operation. While America’s fledgling spy agency was just starting to take baby steps, Britain’s MI6 intelligence service was already at a full gallop, and Bletchley Park was the beating heart of the whole operation. And it was a surprisingly equitable one as well—through a combination of availability (most men were off at war, after all) and smarts (specifically in mathematics, where many of the women shined), 75 percent of the team at Bletchley was female, and together they received encrypted messages that had been intercepted over the radio.

In 1940, the team at Bletchley had broken Germany’s intensely difficult cipher, Enigma. Codes and ciphers, terms often used interchangeably, are in fact distinct. A code replaces the word or phrase entirely, while a cipher only rearranges the letters. Both codes and ciphers make a message secret and comprise encryption. There were thousands of Enigma ciphers being sent by the Germans, and Bletchley Park was swimming in data, only able to decipher a percentage of the transmissions. But as the Allies were finding, breaking the cipher (as huge of a feat as that had been) wasn’t going to be enough.

Even after the jumble of letters and numbers were deciphered, they still didn’t make sense. There were too many acronyms to understand the cryptic transmissions, and then all the individual snatches of conversation needed to be pieced together to comprehend the larger message. The codebreakers analyzed the material, fitting together the pieces of information like a puzzle. When they were done, the intelligence they had gathered, deciphered, decoded, and reassembled was called Ultra.

The group at Bletchley did not decide what to do with Ultra. Instead, the messages were disseminated to a select group of high-level agents at British intelligence and in the newly developed US spy services, who would use the hard-won intelligence to their advantage. These messages were precious and seen only by a small number of operatives. They were code-named Ultra because this prized wartime intelligence was considered elevated above even the highest British security clearance—it was the most secret, most valuable commodity the Allies had.

Meanwhile, half a world away from the front lines in Europe, another Wise Gal was struggling with her own sea of secret messages.

In Washington, D.C., months before Eitel moved to Portugal, his name was revealed in a coded message. It was winter, with air so cold and dry it could make your skin crack, but inside her office, Adelaide Hawkins was dripping with sweat. You might think the trouble was the stress of her job. As chief of the cryptanalysis section, she hired, trained, and organized her team of dozens of men and women. The center prepared messages, encrypting and transmitting them across the globe, before decrypting the replies and routing the messages to the appropriate individuals. Her office was nothing like the Bletchley Park complex across the Atlantic. Instead, the majority of American codebreaking during World War II was handled by the US Army Signal Corps and the US Navy Signal Intelligence Group. Addy’s work was starkly different, yet it would wield a critical and lasting impact. She was on the forefront of an American experiment that would later be called central intelligence.

Addy was a founding member of a group that was fumbling for recognition: the fledgling American intelligence organization called the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS. The OSS was the world’s newest intelligence agency . . . and by far its least talented. The inexperienced US agency could hardly be compared to the well-established British intelligence service, a massive organization broken into MI5 for domestic spying and MI6 for international espionage. Yet the need for an American system of organizing, evaluating, and communicating intelligence operations across the globe was pressing.

On this Saturday morning in February 1943, inside the headquarters of the OSS, the problem was not the gravity of her work. Instead it was the stuffy basement in which she and her team were confined. There was no air circulation, and the room was packed with young people working elbow to elbow, dancing around the room during moments of success, and even occasionally breaking out into song. But no one was singing now. It was too hot. Then the door swung open loudly and General William Donovan walked in.

Donovan was known by the fun-loving nickname Wild Bill, although there was little crazy about his personality. The man who once planned to become a Catholic priest did not smoke or drink to excess. He was sixty years old and spoke in a reserved voice. He had a round face, a head full of gray hair, and blue eyes that, when narrowed at you, reflected the sagacity of his years of experience. All that experience and gravity was put to the test in his current role as head of the OSS.

As he barged into the room, he remarked, “It’s awfully warm in here.”

“I know,” Addy replied mournfully. “The windows are closed and they’ve gone away without working on the air conditioning and I don’t know what we can do.” She gestured toward the small windows above their heads—they were at street level and didn’t appear to open.

Although uncomfortable in the hot basement, Addy rarely complained. She was thirty years old, married with three young children, and she adored her job. She had initially joined the OSS in 1941 as a way to escape her annoying mother-in-law, a prickly woman who had come to live with the family after Addy’s husband was deployed overseas. But she’d grown to love the work and the way it made her feel irreplaceable.

Adelaide Hawkins, 1941.

Courtesy of the estate of Adelaide Hawkins

She sat at her desk and pondered the stacks of paperwork in front of her. We’re fighting for our lives, she thought to herself. I can do this. Yet when her thoughts turned to the men and women suffering overseas, she felt a sharp pang of guilt. If she was being truly honest with herself, she had to admit that she had never been so happy as she was right then, during World War II.

Like the work of everyone on her team, Addy’s work was secret; she could tell no one in her household how she spent her days at the agency. To the outside world, even to her in-laws, she was merely a clerk. Addy found that people rarely questioned her. “Oh, is that so?” they would say, before losing interest in her unimpressive job. It wasn’t difficult for her to keep quiet. Addy felt special, and she knew she was going to hold on to her secrets, no matter what.

The work represented far more than a retreat to her. She couldn’t imagine her life without it. Still, she knew that she was considered a placeholder. Her position as chief was too critical to entrust to a woman, and certainly not one like her, a mere high school graduate from a small town in West Virginia. All around her were men who had graduated from Ivy League institutions, who were lawyers, professors, and journalists. It was only a matter of time before administrators hired a man to fill her position. She would then have to work under him, as a deputy. Whispers about possible replacements were already circulating, and Addy knew that she needed to make herself indispensable if she wanted to keep her job. Right then, however, she was too hot to think.

“Why, you young people can’t work like this,” Donovan said as he looked around and then headed back to his office upstairs. Addy assumed he was getting on the phone to maintenance. Instead, a brown shoe suddenly kicked through one of the windows from the outside and her desk was covered in shards of glass. She stood, openmouthed.

“And a good thing I wasn’t sitting down,” she said.

The solution was pure Wild Bill—bold, immediate, and a touch reckless. Despite Donovan’s age, there were moments when the years rolled right off his back. “Anyone could do it,” he’d say, the excitement spreading across his face as he spoke of an operation’s potential success. In reality, few were as skilled as Addy.

At the moment, Donovan was as animated as a teenager. Addy had decrypted a new message, deciphered its meaning, and then had rewritten its contents, jumbling its letters once more according to their code, so that it could travel secretly to Donovan’s London office and then to Jane Burrell in France. The new intelligence would draw Donovan back across the ocean to London, where he would spend most of the next few years establishing a new group of spies, ones bent on penetration and deception.

Before President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Donovan to create from scratch the OSS (and its elite unit, X-2) in 1942, the United States had no spy agency. Even the remnants of the Black Chamber, a World War I–era codebreaking group, had been shut down decades earlier. What remained were isolated intelligence units serving the army, navy, and Treasury and State Departments, but which did not coordinate with one another. All that would have to change as the US joined the Allied forces in Europe to defeat the Axis powers. But how?

Donovan was a military man, but one who didn’t stand on ceremony or even hierarchy in the manner of many career soldiers. For one thing, medals and awards were unimportant to him. Everyone knew that in World War I he had been awarded the prestigious Croix de Guerre, a French military honor. What was less well known was that Donovan initially refused to accept it. He would not take the accolade until it was also given to a young Jewish man equally as deserving.

Donovan also had a weakness for passionate eccentrics. He often observed that you could teach an operative strategy, but you couldn’t make him care. He was looking for the people who cared fervently . . . and he found them in sometimes surprising places. With little value placed on social pedigree or military rank, Donovan selected a mix of artists, military men, scientists, movie stars, and, surprisingly, a multitude of women, to build the OSS. This first espionage force was instructed in languages and cloak-and-dagger techniques, and trained to kill. One observer described the ideal candidate as “a Ph.D. who can win a bar fight.”

At Donovan’s side was a young woman named Eloise Page. Her friends called her Weezy, but with her boss she was always Miss Page. Where the general was stocky and imposing, Eloise was petite, with high, delicate cheekbones and bright, intense eyes. She was twenty-one years old but moved through the world with the poise of a much older woman. Part of her graceful manner came from her upbringing in Richmond, Virginia, where she grew up in what was called a “first family,” a prominent and wealthy social group that traced their heritage to early colonial settlers.

The last name Page raised certain expectations within her community. Her friends and family in Richmond expected her to marry well, start a family, live in the right neighborhood, and move in the proper social circles. Had World War II not intervened, it’s possible that Eloise might have fulfilled those hopes, although not likely. She did not care much for others’ expectations, often telling her mother, “I know my own mind.” Her friends would say she was “born to be a leader.” A fresh college graduate with idealistic ambition, Eloise was searching for purpose, and she found one while living in London and working a low-paying job under difficult wartime conditions. She was General Donovan’s secretary.

Eloise Page.

Courtesy of the estate of Eloise Page

The position was more akin to an aide-de-camp. Eloise not only organized and typed Donovan’s correspondence, but she also helped write its content, as well as discuss strategy, organize Donovan’s travel, and arrange meetings. It was a mountain of responsibility for a young woman who was habitually late for her own appointments. Still, Donovan leaned on her: a year earlier, she had played a pivotal role in Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa, and the first jointly planned operation between the United Kingdom and the United States. Hunched over reports and maps, carefully labeled with potential landing sites, Donovan and Eloise spent late nights together organizing the intelligence OSS had collected.

She had not always been so bold with Donovan. Initially she’d stood in awe of the general, but soon she learned to withstand the variabilities of her boss’s hot temper and realized that he actually wanted her opinions. He loved to debate military and espionage strategy as much as she loved shaping his decisions. Although Donovan was known for his extramarital affairs, his relationship with Eloise was professional.

Donovan was accomplished at identifying young, talented individuals. In Eloise he recognized exactly the kind of woman he needed. With her Southern accent and diminutive size, she appeared a pampered socialite. Yet inside the tailored dresses and white gloves, Eloise never flinched. She was surprisingly tough and capable. While her family and friends saw her as a secretary, likely to return to the social set of Virginia after World War II, in reality she was already on her way to becoming a bona fide spy.

By 1943, Eloise was passionate about developing their X-2 network, the elite group of counterintelligence agents who acted as liaisons between British and American intelligence. Admission into X-2 was highly selective. Not only were its officers privy to the secrets behind wartime intelligence, but they also had the power to veto military operations without disclosing their reasons for doing so. It was the vision of this group of agents that dominated American counterintelligence operations in the final years of World War II. Eloise’s strength lay in fostering relationships with British intelligence. As the name Carl Eitel passed back and forth between American and British intelligence, it was clear to both her and Donovan that this was a key opening for their new X-2 agents in Normandy.

Jane Wallis never expected to be living in France. When she’d applied for a government job back in 1941, she remembered seeing a line on her job application that read, “If you are willing to travel, specify: occasionally, frequently, or constantly.” Jane had marked an X next to “occasionally,” hoping for the least amount of travel. It didn’t work out that way.

Born and raised in Iowa, Jane found escape in the study of language. Fluent in French, she studied abroad, in Montreal and Paris, and traveled throughout Germany, Italy, and Spain. She had intellectual potency, graduating with a joint degree in French and English literature from Smith College in 1933. Her family would describe her as “witty and pretty” with dark brown hair, bright blue eyes, and an exceptional mind.

Immediately after graduation she eloped, marrying a man named David Burrell. She assumed her travels were over, and she settled into a life focused not on her love of language and words but instead filled with the expectations of a housewife and mother.

The children Jane hoped for never came, and instead of a house filled with babies, she found herself alone after her husband was deployed. Like so many women, Jane was determined to find her own role in World War II. The female labor force grew by 50 percent between 1940 and 1945, with 25 percent of all married women working outside the home. In 1942, Jane would become one of them, joining the OSS as a junior clerk, at an annual salary of $1,440. Men in her position, with the same education and experience, were starting at an annual salary of $4,600.

Jane Burrell, Bois de Boulogne, Paris, 1945.

Courtesy of the estate of Jane Wallis Burrell

She first worked in the Pictorial Records Section of the OSS, where bundles of photographs of various sites in now-Axis-occupied Europe were dumped on her desk, sorted by region. Her department’s task was enormous—there were more than a million pictures to analyze—and in those confusing early days of World War II, the work was critical. Almost all the pictures of Europe had been taken years before, during the peaceful prewar days. Now, those same images allowed the Allies to re-create detailed and (more) current maps of the landscape where their soldiers would soon be fighting. The US government was placing advertisements in magazines and on the radio, asking citizens to mail in their pictures of European vacations. Pleas for more photographs regularly circulated throughout government agencies. “Possibly some of you possess a photograph,” read one such request, “which, if properly used, could be a more deadly weapon than ten torpedoes or twenty tanks.”

The pictures were used to identify targets and coordinate strategy. With a magnifying glass in hand, Jane went through the images, looking for clues. She often found herself in familiar territory, identifying streets in France that she had strolled down in real life. The work was tiresome, requiring an eye for detail and a patience to go back over the same images repeatedly. The results, however, were sometimes spectacular. Just by piecing together the blocks of a street in a small town in Germany from the snapshots of an American tourist, Jane helped lead to the destruction of a Nazi asset.

It wasn’t long before the quality of her work brought her to the attention of her supervisors. James R. Murphy, chief of OSS counterintelligence, was impressed with Jane’s analysis and her proficiency in languages. He decided that she was ready for more. In July 1943, she received a letter that would alter the course of her life. It said that she was being transferred overseas, stating with typical bureaucratic terseness: “This transfer is not for your convenience, but in the best interests of the Government.” The letter had been sent from the OSS.

The OSS was composed of novice American agents who were untested and very green. At first, the British wanted little to do with their American counterparts, who were more likely to bungle their plans than to actually assist in operations. They made an exception for one elite section of the OSS called X-2.

X-2 was made up of the best spies and communication officers the United States had at that time. These officers were specifically working in counterintelligence, which was related to (but distinct from) intelligence. Whereas espionage acquired information through clandestine operations, counterintelligence destroyed it. And in the case of X-2 counterintelligence, they were working hard to destroy the network of spies sent to infiltrate the Allies’ efforts during World War II.

Instead of looking at photographs of vacations gone by, Jane was now firmly in the present. She traveled through the towns and countryside she had studied in detail, rarely getting lost. The intelligence she was receiving in X-2 was very different than mere photographs. It was the only division to receive raw Ultra material. As Jane sat at her desk in Normandy and held the German intercept that named Eitel, she felt fortunate for the convoluted path that had brought it to her—from Bletchley in the UK, through Donovan’s situation room in Washington, D.C., to her small room in France. Little did she realize that the intelligence had passed through the hands of many hardworking women, just like her, who were doing vital work to win the war. Working as an intelligence officer was a career that hadn’t existed a few years earlier, but now Jane valued it above all else—even her marriage.

Thanks to Donovan, X-2 was bustling with female officers, and Jane developed a diverse group of friends and colleagues overseas. They bonded over the urgency of their work, even as they kept the details of their operations confidential from one another. Their positions were critical, as officers had to recruit, develop, and handle their own spies. It was late 1943, and Jane was ready to initiate contact with Eitel.

British intelligence was wary of working with newcomers like Jane; they eyed her and the X-2 unit with suspicion. While the Americans were struggling to start a spy organization, the British foreign secret intelligence service, MI6, had been operating in Western Europe for decades. Even as they were helping to establish X-2 as their American counterparts, they were hesitant to hand off responsibility to new agents.

However, Jane was not just any agent. She spoke French like a native, wore her hair and makeup like a Parisian, and made friends wherever she went. Ever since she was young, Jane blended seamlessly into situations. She had spent her life playing a series of roles expected of her: that of Midwestern daughter, then student, and finally housewife on a dairy farm. However, it was only now, as an American spy in France, that she felt she could be her genuine self.

The OSS station in Normandy where Jane worked was a villa with whitewashed walls and purple climbing wisteria vines. Inside, agents sat in a living room scattered with newspapers from multiple countries or moved quietly downstairs to a basement converted into a code room. From this base of operations, Jane plotted her strategy.

Meeting with Carl Eitel was simple. Selecting a time when she knew no one would be home, Jane and another agent entered his apartment building at 14 rue Victor Hugo unseen. They picked the lock at his door, ignored his belongings (which had already been searched by British agents), and then waited for him to come home. They weren’t waiting for long.

It turned out the difficulty in this operation wasn’t finding Eitel (he was hiding in plain sight); it was turning the German intelligence agent to work for them. At first Eitel was willing to admit to almost nothing. According to him, he had worked for Abwehr for only two years. He said nothing of ocean liners, espionage in the United States, or his recruitment of agents. Jane began pressuring him, with threats of turning him over to the British or possibly to the Soviet Union. Most German intelligence agents would do anything to avoid the Soviet Union, whose treatment of enemy agents was rumored to be painful and deadly. The threat worked. Eitel, the son of a French mother and a German father, with close ties to his Jewish sister-in-law, had no real loyalty to anyone but himself, and so he agreed to work for the Allies.

Eitel would become a key part of a sensitive operation that Jane was part of: Operation Double Cross. MI5, Britain’s domestic secret service, and MI6, the foreign branch, had been amassing a network of turned German spies who could be used against the Nazi intelligence service. Now, X-2 was joining the operation, recruiting and handling their own agents. Jane was working closely with British agents whose backgrounds appeared unblemished and whose loyalties seemed clear.

Working with another X-2 officer, Lieutenant Edward R. Weismiller, a Rhodes scholar with degrees from Cornell and Harvard, Jane began extracting information from Eitel.

“Who is John Eikins?” Jane asked.

Eitel was surprised. “How did you get that name?” he sputtered. But Jane refused to reveal that their source came from an Ultra communication. They couldn’t risk the Germans finding out that the Allies had cracked the Enigma cipher.

Instead, Weismiller laid a heavy gold ring on the table. It was the perfect bribe for a man who loved to sparkle. With his new jewelry, Eitel revealed the name of the man he had spent the past nine years working with: Juan Frutos. He described him as a young Spaniard, a man who sometimes went by the pseudonym John Eikins, one of many agents Abwehr had sprinkled across the French countryside.

As soon as Jane and her team of X-2 agents had Juan Frutos’s name, they began monitoring him. He was based in the French port city of Cherbourg. When he and his girlfriend left their apartment, the American agents broke in and combed the place. A cache of letters proved to be a treasure. They found some from Eitel, corroborating their relationship, and others that seemed suspicious—a network of spies for them to track down, although they couldn’t be sure the names were real. It was time to make contact.

Frutos had a lot to lose. He had two young sons, a wife . . . and a girlfriend. Even with these incentives, he didn’t want to tell Jane anything. She knew Eitel had recruited him, but Frutos wouldn’t tell her how long he had worked for him. He wouldn’t even admit that he knew Eitel was a spy, instead only saying vaguely that he had suspected it. He certainly was not ready to reveal that he was a “stay-behind agent” in France, one of a number of men and women spying on Allied positions and troop movements along the coast.

As Jane questioned Frutos, her frustration grew. The man was pretending that he couldn’t remember names or dates. He stumbled in his speech, refusing to give details and rambling on about Spain. Jane knew that while getting information from Frutos was important, the most crucial task was recruiting him to work for her and the Allies. It was clear that Frutos was not an idealist; certainly he was not devoted to Germany or that country’s ideals. Rather, he was merely a man trying to save his own skin. She wouldn’t even need a gold ring to pull him to their side.

Jane reasoned with Frutos, acting as his friend and working on his confidence. She promised him some money and told him it would be in his best interests to come over to her side. Other agents stressed that they knew he was lying and that the consequences would be bleak unless he cooperated. They kept up the pressure, holding Frutos for five long days until they were able to turn him. The real exertion, however, was still ahead.

Jane pondered the value of her newest spy. To some, it might have seemed that he was just one unimportant man, a mere underling in the vast army of Allied operations. His loyalties were hazy and his intelligence limited. Yet in the distance, Jane, along with a select group of her colleagues, was preparing for an invasion of staggering proportions. A future was emerging where this one man, buried deep behind enemy lines, would play an essential role. This glimpse of victory, however, could emerge only if Jane was able to control him.

Running agents was dangerous, complex work. It required intimate knowledge of the operation, the enemy’s position, and the Allies’ immediate and long-term goals. It was also frequently deadly. A quarter of all espionage agents in France were killed, and those numbers were even higher for women operatives. Female couriers were a common target for the Gestapo, and even the possession of a wireless radio was a crime that carried a death sentence.

Jane was responsible for a handful of agents. She met with them covertly, assessed their abilities, and clearly defined their roles in an operation. She monitored Ultra transmissions to ensure that information was being passed appropriately and that her agents were acting on the counterintelligence as X-2 predicted. They called it a “closed loop” system because they could feed the information to the Germans and then watch it come out the other end in Nazi communications. With sophistication and caution, Jane constantly tested her agents’ new loyalties.

In May 1944, with speculation of an imminent Allied invasion at a fever pitch, Abwehr sent Frutos two radio sets and strict instructions to report on the arrival of ships, numbers of soldiers, their weaponry, tanks, and artillery. Here was an ideal opportunity for Allied intelligence operations, but the intrigue proved too much for Frutos. In fear for his life, he hid both radio sets in the attic.

Frutos had gone dark.

With British intelligence struggling to control the wayward spy, X-2 agents took command. By July 1944, they had convinced Frutos to continue. He was too far in to back out now. That summer, Jane began calling Frutos a new name. They had played with the code name Pancho before finally deciding on Dragoman. With German intelligence focused on Dragoman and his suspicious, intermittent reporting, Jane was imperiling both their lives with every contact.

Jane knew that time was crucial to their operations. Every day that Dragoman was quiet would inflame the Germans’ suspicions. With nail-biting anxiety, Jane checked the Ultra messages incoming from Bletchley, searching for clues. She suspected Dragoman was being watched, although she didn’t know who among the modest countryfolk living alongside him might, in reality, be a German spy. X-2 was reporting there were at least two Abwehr agents living in Dragoman’s neighborhood. They might sniff out the truth at any moment. If he was even suspected of working with the Allies, the game was over.

Meanwhile, X-2 was losing control of Dragoman/Frutos’s other contact, Eitel. He was bragging to his friends that he was secretly working for the Americans, showing no discretion whatsoever, while simultaneously missing liaisons arranged in Paris with X-2. Even worse, in early 1944, he traveled to Berlin. What is he doing there? Jane and the X-2 spies wondered. The Americans did not know the purpose of his trip, but they certainly had their suspicions. Arresting Eitel upon his return, they found his responses contradictory and unhelpful. Something needed to be done about this potentially rogue double agent.

One line in an X-2 agent’s report underlined the danger Eitel was in if they couldn’t match his accounts: “If such [a] story is not proved, he should be executed.”

Eitel might have been faltering, but Dragoman was finally beginning to prove his worth. His secrecy was critical, as Jane knew he would play an important role in X-2’s next, most vital mission: Operation Jessica. The plan was part of a larger deception run by the Allies.

If Allied forces were going to successfully invade Western Europe following the D-Day landing in France on June 6, 1944, they needed to overtake strategic French port cities. These key locations could supply the invading army with reinforcements and supplies, assisting Allied troops as they moved through France and into new combat zones. The operation was delicate: the Germans needed to believe the Allies were present in large enough numbers along the border between France and Italy so that they would hold the position of Nazi troops and U-boats, but not so large that they would preemptively attack. Meanwhile, the Allies were focused on France’s Brittany coast, a region located west of the D-Day landing sites that would be critical for the invasion of the continent. As luck would have it, it was here that Dragoman resided as a stay-behind German agent and spy for X-2.

The port city of Brest, France, Eitel’s stomping grounds, was now considered vital for the Allies to overtake. To fool the Germans, the Allied forces employed life-size imitation ships, tanks, and aircraft in decoy locations surrounding Brest. But this ruse had a flaw: by itself, the inflatable equipment was comical. It looked real only from a distance, and to give the ploy credibility, the Allies needed the corroboration of their double agents. In a coordinated effort, the British secret service and X-2 instructed their spies to flood Abwehr with misinformation.

As Jane and the X-2 team readied Dragoman to be a trusted source of (false) information for the upcoming invasion of Brest, they first gave him real intelligence on Allied operations to prove his worth to the Germans. It was a nail-biting moment. They hated giving the Germans any genuine information on their troop movements or locations. Yet Jane knew it was a necessary evil if Dragoman was to gain the trust of Abwehr. They planned to give the Germans just enough credible intelligence for them to believe Dragoman, and then they would begin their true mission of misdirection. This proved challenging, as Dragoman’s previous messages to Abwehr were brief and lacking in detail, and an abrupt change would prompt suspicions. They raised the character count slowly, from eighty words up to ninety, until they stretched the reports into pages. The messages worked. The Germans were impressed with Dragoman’s more detailed reporting, little suspecting that X-2 agents had written the transmissions.

The inflatable army was a success. Allied forces soon overtook Brest and Dragoman’s spying gained critical importance. In December 1944, the German offensive campaign in the Ardennes Forest between Belgium and Luxembourg forced Allied forces into the Battle of the Bulge. Under the direction of Jane and X-2, Frutos responded by obtaining technical details on anti-torpedo nets used to protect ships from German U-boats. Frutos gave considerable data not only on the anti-torpedo nets but also detailing convoy routes and describing the vast damage caused by the German V-bombs. Every word was false. X-2 agents crafted each transmission, working together to edit the text until it meshed perfectly with all the information they and MI6 had fed the Germans.

In the last days of 1944, Allied troops were able to reinforce and resupply their forces in the Battle of the Bulge from crucial French port city locations, while the fearsome German U-boats sped toward the sites X-2 had directed them to, far from resupply lines. Speaking of Dragoman, one report read, “[x] might have had a decisive influence on the whole German U-boat campaign in American and British waters.”

Jane—and the network of X-2, OSS, and MI6 spies across the world—had saved countless Allied troops’ lives.

Multiple (secret) reports written in 1945 heaped praise on Frutos and his role in tricking the Germans. The same cannot be said for Eitel.

Following his arrest in France, Eitel was brought, unwillingly, to England. No longer needed by X-2, he was interrogated by the British secret service and was treated as one of many German agents being questioned following World War II. Despite the key role he played in leading the Allies to Frutos, Eitel’s allegiance was murky at best. No one could be sure if he had been under X-2 control, or really an agent of Abwehr, or some perverted combination of the two. The investigators carefully lined up his stories, trying to ferret out the truth. They showed him dozens of photographs, testing his knowledge of German agents but also hoping to gain his collaboration. He detailed his early history in espionage, but the end of his career was poorly defined. “He appears to be three different men,” read one report, connecting Eitel with two other names he used: Gross and Eberle.

At the end of 1945, reports made from Camp 020, the interrogation center in London where Eitel was held, describe his health as good. No one knows what happened to him after that. He never returned to his bistro or to his girlfriend. One cryptic line is found in his files: “A sad end for a double agent.” A list of his personal belongings, which appear to have been unclaimed, included cash, clothes, and a large collection of gold jewelry.

While the fall of 1944 was the beginning of Eitel’s end, as both a spy and possibly as a man, the Wise Gals basked in its glory. By early 1945, the momentum was building in their work. Yet even as they came tantalizingly close to what they hoped would be Germany’s surrender, they could see the long tail of the Third Reich following them.

Both Eloise and Jane were troubled with one particularly frightening intelligence report. It concerned a meeting that took place on August 10, 1944, at the Maison Rouge hotel in Strasbourg, France. In attendance were the titans of German industry: the leaders of IG Farben, Krupp, Leica, Messerschmitt, and Zeiss, among others.

The events of 1944 had brought clarity, even to members of the Nazi Party, that Adolf Hitler’s regime was coming to an end. In response, the men who had massively profited off the Nazis gathered to protect the enormous wealth they’d accumulated. Their plan was clear: transfer the money to Swiss bank accounts, then divert the money to shell companies in neutral countries. They knew the Swiss would be amenable to the proposal, especially if they gave them 5 percent of the profits. Once the world cooled off, the money could be used to fund the Fourth Reich. An underground movement to hide Nazi treasure, gold, jewels, and artwork was spreading across Europe.

The Wise Gals were sharply aware that the Nazi Party would not go quietly; they would merely blend in with their surroundings. Like cicadas, they would remain hidden underground, waiting years if necessary, until the world was ripe for their resurrection.

It was time to get digging.

CHAPTER TWO

SAFEHAVEN

1944–1945

He’s impossible, Eloise thought, her frustration mounting. Unreasonable, and totally thoughtless. She had been up until three in the morning with her boss, General Bill Donovan. It was early May 1945, and they had spread their operations across an entire floor of Claridge’s, central London’s swanky five-star hotel. The hotel was perhaps too polished for the Americans’ endeavors. In rooms considered worthy of royalty, they plotted strategy, bribery, and even deadly retribution.

Eloise was accustomed to the long hours—after all, she’d been working for the brilliant, mercurial Wild Bill for three years by now—but her irritation intensified when, upon returning to the makeshift office four hours later, Donovan asked, “Is the dictation done?” She wanted to scream. Instead she merely replied, “No,” and drew up her chair to the typewriter. Donovan’s unreasonable expectations rattled her.

One might have thought that the end of the war would mean less exertion and pressure for Eloise. Instead, the burdens were building. Donovan wanted to build a permanent American organization that echoed the sophisticated success of British intelligence operations, but he found support wavering in Washington. The OSS was fragile, an organization that could be easily crushed by politicians who saw the end of World War II as the termination of big government.

Victory was a temptress, potent to those who would prefer to leave Europe and the costly rebuilding of the continent to others. To do so was to close one’s eyes to the threat of potential conflict as well as the punishment of prior evil. Even as they fought the war, Donovan was preparing for the eventual prosecution of Nazi war criminals. As early as 1943, he suggested holding the trials in Nuremberg; he wanted the Third Reich to symbolically fall in the place in which it had originated.

In order to try them in court, however, the criminals had to be caught. After four years of training with Donovan, Eloise was ready. As she typed up his dictation in London, connected his phone calls, and responded to his mail, she knew that each administrative act was nearly her last. Soon she would immerse herself in the world of spycraft and leave the secretarial drudgery behind. She would not mourn the change. Being a secretary for Donovan was demanding, and she yearned for the next phase of her life to begin.

While Eloise relished what lay ahead, her parents fretted over her future back in Richmond, Virginia. As the rolling hills of the Shenandoah Valley turned from brown to bright green with the warm rains of spring, so was life returning to what it had once been. Even before Germany formally surrendered, men were returning to their jobs, women were leaving the workforce, and the rations on food, gas, and even toothpaste were lifted. Yet Eloise still didn’t come home.

When their daughter did return, late as usual, she was home only briefly, to pack up a few of her things before leaving for good. She wasn’t telling her family many details about her new career. They understood that she wasn’t a secretary anymore, but in Eloise’s vague job description they couldn’t piece together exactly what she would be doing.

Her mother could still remember what it felt like to see her eleven-year-old daughter cross the stage at the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore. The young girl, in her best white dress and with her hair curled, had fearlessly sat at the piano and begun to play. After her fingers touched the last keys of the piece, she stood up and curtsied in front of the audience. As she clapped at her daughter’s performance, it seemed she was seeing into the future. She pictured Eloise grown into a musician, her talent in the arts unparalleled. When Eloise was accepted into Hollins College in Roanoke, an exclusive women’s college, and majored in music, she was certain this vision would be realized. Now her world had been shaken off its axis with a single sentence from Eloise: “I’m moving to Brussels,” she said.

“Working for that general?” her mother asked.

“Yes, and I’m working for the government . . . ,” Eloise said, keeping her phrasing ambiguous. “In intelligence.”

“Isn’t that a strange profession?” asked her mother. Eloise just shook her head; she had nothing to say.

During the war, Eloise had understood who her allies were and which countries they were fighting against. Now, in 1945, nothing was clear. She was entering a country tangled with loyalties she did not fully comprehend—with consequences she couldn’t yet fathom.

What would happen if the former “good guys” became the enemy?

It started with a gunshot.