Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

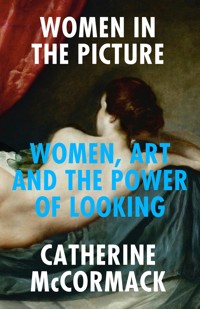

'Incisive and provocative ... a sensitive and probing critique' The New York Times 'Essential reading ... gripping, inspirational, beautifully written and highly thought-provoking' Dr Helen Gørrill, author of Women Can't Paint A bold reconsideration of women in art - from the 'Old Masters' to the posts of Instagram influencers A perfect pin-up, a damsel in distress, a saintly mother, a femme fatale ... Women's identity has long been stifled by a limited set of archetypes, found everywhere in pictures from art history's classics to advertising, while women artists have been overlooked and held back from shaping more empowering roles. In this impassioned book, art historian Catherine McCormack asks us to look again at what these images have told us to value, opening up our most loved images - from those of Titian and Botticelli to Picasso and the Pre-Raphaelites. She also shows us how women artists - from Berthe Morisot to Beyoncé, Judy Chicago to Kara Walker - have offered us new ways of thinking about women's identity, sexuality, race and power. Women in the Picture gives us new ways of seeing the art of the past and the familiar images of today so that we might free women from these restrictive roles and embrace the breadth of women's vision. 'A call to arms in a world where the misogyny that taints much of the western art canon is still largely ignored' Financial Times 'It felt like the scales were falling from my eyes as I read it.' The Herald

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my beloved S&D, that they might see the world clearly. And to Barny, for that spider diagram all those years ago.

Contents

Preface

At first glance, there was nothing unusual to see. A story was unfolding across three panels in an art gallery. At its centre stood a long-haired woman surrounded by a lot of men in tights and a menagerie of animals. In the painting, men talk a lot. Big dogs bark at smaller ones, their fur fraying and their eyes bewildered. In one panel, a small, depressed-looking bear is delicately chained to the decorative architecture. In a few instances, the same long-haired woman appears stripped naked, and even the dogs in the image look at her with pity, their ears down, feeling the heat of her shame.

Master of The Story of Griselda, detail from The Story of Griselda, Part 1: Marriage, about 1494. © The National Gallery, London

I was in the Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery, bouncing my fractious baby on my hip, trying to keep engaged with my work as an art historian and educator after the birth of my second child and keen to view the gallery’s rehang of its Renaissance collection. I wanted to see which works had come out of their dark and silent storage like time-travellers to the present. After all, museums’ collections are not static: they get rearranged and reconfigured, making pictures from the past speak to one another, and to the public who owns them, in endless ways.

And this story of the long-haired woman definitely had something to say. For, while I was looking more closely at the panels, a man appeared at my shoulder. ‘I wouldn’t look too deeply into the symbolism in this one,’ he said with a note of warning. ‘The message it promotes isn’t fashionable at the moment.’

His manner was both avuncular and imperious. ‘Oh?’ I replied with a nervous laugh, taken by surprise by the unsolicited commentary delivered so close in my ear and so close to my body. ‘But this symbolism is exactly what I am interested in, you see. I’m an art history lecturer and I’m preparing for a course I’m teaching on feminist art history and the depiction of women in paintings.’

But the man in the gallery didn’t listen to me. He just saw a woman with a baby, a woman who was not too young to be unapproachable, but young enough that he expected me to listen to him when he wanted to talk. He saw me as a mother, and perhaps not so much as a mind. I wanted to be rid of him, but I also wanted to look at the painting and didn’t have much time. So I stayed in that room, with this man who needed me to know that he knew this troublesome story, narrated in a painting that had at one time hung in a home in Italy in the late fifteenth century. The story goes like this.

An Italian marquis known as Gualtieri was reluctant to marry, but knowing he needed an heir, he set out to find a wife. He found a peasant girl called Griselda, who was well known for her virtuousness and obedience. Still, Gualtieri needed to be sure that this peasant girl was going to always do exactly as he asked, so he put her through a series of cruel tests to prove her constancy (sometimes known in medieval literature as the ‘wife-testing plot’). First, he stripped her naked in public, ostensibly to reinvent her in the clothes of her new noble life, but conveniently exposing her body to humiliation and the mercy and desire of his and the public gaze. Graciously accepting this indignity, she had passed the first test. After their marriage and the birth of their first child, he ordered that their newborn daughter be killed without explanation. The child was taken away, and Griselda was forbidden to ask any questions. When Griselda bore a son, he too was taken from her and killed on his father’s orders. But Gualtieri had secretly ferried his children to other families. Then, he dissolved the marriage. He dismissed Griselda from their home, stripping her once more of her clothes and her claims to any status. Many years later he invited her back as a servant, and gave her the task of preparing a banquet for his new wife. Ever tacit and compliant, Griselda agreed. But the new marriage was revealed to be a trick – and the ‘bride’ was revealed to be the long-lost daughter. Griselda was ‘rewarded’ for her constancy and compliance, and was finally granted her role as wife and mother in a noble family.

With tired patience, I listened to this tedious ‘mansplaining’ of a story of unmitigated misogyny, smiling to myself, thinking how funny and ironic this was going to be as an anecdote to share with my students, who would inevitably all be women. And how we would all laugh about the crude and ridiculous posturing of men inside and outside of pictures. But I also knew that really it wasn’t funny at all, and that the laughter, camaraderie and camp indignation we would treat it with, tutting with the exasperated retort of ‘MEN!’, was really a way of not despairing, because this sort of thing happened so often that it felt like the inevitable order of things. The painting’s message was also inevitable for any fifteenth-century bride. The husband was master, to be obeyed at all costs. Abuse was to be endured, marriage and motherhood the ultimate prize. In the final panel’s scene, Griselda is embraced and kissed by Gualtieri, but she has the lobotomised glassy stare of an obedient automaton stunned into submission, like a Renaissance Stepford wife.

The three panels that make up the ‘Story of Griselda’ are among the National Gallery’s collection of over 2,300 paintings. Among these are some of the world’s favourites – Van Gogh’s sunflowers wilting in a vase, Seurat’s proletarian swimmers at Asnières, Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks. Over the past twenty years I have been inspired and delighted by the details of so many works in the collection: the reflection of the clouds in the stream in Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ; the detumescent Mars in Botticelli’s joke about men rolling over after sex in his panel painting of Venus and Mars; the bristlingly red room of Degas’ La Coiffure; the silhouettes of the birds seen from the window of Antonello da Messina’s impossibly detailed study of Saint Jerome. But there are also the things I can no longer reckon with: things that I see, which cannot be unseen. Irritated by my encounter in front of The Story of Griselda, I turned the corner and found a woman on the ground with her throat pierced, oozing blood from her jugular and with a deep gash on her forearm; her wrists already hooked with rigor mortis; her high round breasts and gently curving stomach egregiously exposed. The only witnesses were a satyr and a mastiff, both looking on vacantly at the dying woman, the dispassionate limpid blue of the horizon flatlining any of the scene’s horror.

Piero di Cosimo’s undated painting is given the loose title ‘A Satyr Mourning over a Nymph’, but the narrative draws on the mythological story of Procris, who was suspicious of her husband Cephalus and spied on him by hiding in bushes in the forest where he hunted. When he called to his beloved Aura to ‘come into his lap and give relief to his heat’, Procris stirred, creating a rustling in the bushes, and Cephalus shot her thinking she was a wild beast. It is a cautionary tale about the fatal consequences of wives spying on husbands.

On my way to the exit I passed by the malignant biblical story of Susanna and the Elders, the comely young woman spied on while bathing by two lascivious old men who say they’ll denounce her as an adulteress unless she sleeps with them. I walked past the figure of the mythological nymph Leda, curled into a conch-like shape as she is violated by the god Zeus who has taken the form of a swan. I glanced again with a shudder at a portrait of a woman posing as Lucretia, the Roman noblewoman from Livy’s histories who killed herself with a dagger to her breast to atone for the shame brought on her family after she was raped.

Seeing these images in their heavy gilded frames, tenderly lit and guarded by tasselled ropes and attentive guards, somehow made male desire and violence both precious and part of the unquestionable natural order of things. They seemed to celebrate the fact that female virtue is rewarded when it is bravely guarded, and that threatening male behaviour is tolerated. They celebrated that being the focus of male sexual desire is an honour (if you are Leda) unless it sullies the patriarchal bonds of honour because you are owned by another male (if you are Lucretia or Susanna), in which case the victim always pays the price for the crime.

The walls of our galleries have a sacrosanct charge that absorbs any censure. Oil paint is a soothing medium that smooths out the brutality and double standards of these narratives and turns them into lessons in culture and civilization for the general public. But what other alternative histories lie buried in plain sight beneath the gilded frames, the imposing ceilings, the tasselled ropes and the protective glass surfaces that deflect proper scrutiny? What discomfiting things are we prepared to overlook in the name of ‘beauty’ and the art-historical concepts of value, ‘genius’ and achievement that we tend to so readily accept? Through whose power and at the expense of whom did they even get here?

Explanatory wall-text often casts no judgement, focusing instead on artistic invention, achievement, style or value – and a pat on the back for the mostly male artists for their singular genius.

The mostly male artists.

While there is no shortage of pictures of women on the walls of the National Gallery, in a collection of 2,300 paintings, only 21 are actually by women.1 It is a discrepancy that the gallery has only very recently openly recognised. The National Gallery is not the only collection with this problem – the invisibility of women artists is part of a much wider, pervasive system of exclusion. In 2019 the Freelands Foundation annual report on gender disparity in the creative arts sector found that 68 per cent of artists represented by London’s top commercial galleries were men, and only 3 per cent of the top-grossing works at contemporary art auction were by women. This is despite the fact that women take up more than two thirds of places on creative arts and design courses in higher education.

The statistics are even worse for artists of colour; the Black Artists & Modernism’s National Collection Audit found that there are only around 2,000 works by black artists in the UK’s permanent collections. In the US, African American women make up just 3.3 per cent of the total number of female artists whose work was collected by US institutions between 2008 and 2018 (190 of 5,832).2

This absence of women as creators and professionals can be felt not just in our prestigious national collections of art, but also in the public spaces of our cities. The Public Monuments and Sculpture Association of the UK has a database of 828 known sculptures on its (non-exhaustive) inventory. Just one fifth of these are sculptures of women. But this number represents sculptures of women’s bodies. When we take away the statues of nymphs and generic nude female figures (for example, representing allegories or symbolising geographical locations), then the actual number of sculptures of named women from that total of 828 is reduced to just 80. Almost half of these are of royalty, many are of the Virgin Mary, and none of them is of a female politician. (By contrast, there are 65 sculptures of named male politicians in public spaces around the country.)

Historically speaking, women have not been allowed to look; held back from studying and entry into the professional sphere, they were not allowed to look at books nor at the world – more specifically, they weren’t allowed to look at the world of men, in case they found something that they wanted to challenge. This restriction also meant that women have historically been excluded from looking at bodies, either as doctors or as artists. This privilege not only gave men near total control over the way women’s bodies worked but also over the way women’s bodies have appeared, in everything from paintings and sculptures to medical textbooks, cinema and political cartoons – and these representations are not necessarily reflective of the myriad ways in which women see themselves.

Some of our best loved works of art are about stopping women from seeing: John William Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott (1888) hangs in the collection of Tate Britain in London and consistently features in polls of the UK’s favourite paintings. Its subject is taken from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s 1833 poem of the same name. It is about a woman trapped in a tower, under a curse that stops her looking directly at the city of Camelot. Instead she is only allowed to see the world through the reflection of a mirror and must obediently get on with weaving representations of it. One day she tires of seeing the world mediated in this way and looks at the passing knight Lancelot, with whom she falls in love. For this she must die. The curse erupts. She climbs into a boat in a white dress and floats away down the river until, as Tennyson puts it in his verse, ‘her eyes were darken’d wholly, and her smooth face sharpen’d slowly’. Like the fate of Procris, shot by her husband, the story is about the perils that afflict women who look.

While paintings of flowers and landscapes were just about tolerated as a hobby for the amateur ‘lady-painter’ as part of her portfolio of charming talents, women were excluded from professional training in art academies. Up until the twentieth century, formal, academic art training always emphasised the mastery of drawing the nude body as the foundational bedrock of everything, in the form of the ‘life class’ or ‘anatomy class’. And the nude model, especially the male nude, provided the basis for the sorts of paintings and sculptures that communicated lofty ideas about humanity, culture and civilization, and religion – the sorts of subjects that made it onto murals, church altarpieces and ceilings in the palaces of the powerful, or as sculptures in public places. The male nude body in art, from its very beginnings in ancient Greece, was about heroism, strength and even intellect. And images of nude, white men subsequently became the normal signifiers of not only the infallible period of classical antiquity and all that was considered impressive about white European civilization, but also of any worthy cultural and intellectual ideas.

But there was such anxiety over the thought of a group of women scrutinizing and understanding a nude male body that women were almost entirely kept out of professional artistic training until at least the end of the nineteenth century, and even up to the middle of the twentieth century in the UK. Among the founding members of the Royal Academy in Britain in 1768 were Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser – two women artists who had managed to slip through the institution’s systemic gender discrimination. This presented a problem when Johann Zoffany produced a group portrait of the founding members. In his painting The Academicians of the Royal Academy (1771–2), a bevy of cultivated men gaze with reverence on one of two nude male life models, their eyes twinkling with inspiration, their expressions settling into satisfied recognition of something approaching the divine. In the foreground, looking out to the viewer, the other male model sits casually peeling off his stockings to add to the growing tumble of clothes on the floor at his feet. Beneath him the sculpted nude torso of a woman’s limbless body lies on the ground, skewered by the walking cane of the green-jacketed man beside him. Zoffany’s painting leaves us in no doubt as to whose bodies count when it comes to the production of ‘great’ art, and whose are treated as little more than meat.

The presence of these two nude men in the studio erased the possibility of any women appearing in the scene, whether they were artists and founding members or not. In order to tolerate their presence, Zoffany turned Moser and Kauffman into pictures and hung them on the wall (above the two men in black on the right-hand side), where they appear as painted portraits, not as people. Let me put that in different terms: women – even when they were seminal artists themselves – could only be depicted as they were seen by others and not in the act of seeing the world themselves.

After the demise of these eighteenth-century women, whose presence within these circles was so precarious, another woman was not elected as a full member of the Royal Academy until 1936. In the minds of the British establishment, therefore, there were no women artists between 1768 and 1936.

The anxiety about women looking at naked men in the studio and manipulating their bodies at will with their pen or brush is at the crux of everything. It is an admittance that looking, and who gets to look, and make art, is more about power and control than we might first be inclined to think. It is about who gets to tell their version of the story and who makes an object out of whom. It is also an admission that men and women’s bodies have historically always been seen differently.

And because, until recently, men have had almost exclusive access to creating our cultural images, they’ve also been able to control the archetypal constructions of womanhood that have influenced ideas of how women should appear and how they should behave, from the meek and patient Virgin Mother, to the always-available, sensuous Venus pin-up, or the vulnerable damsel in distress to the terrifying witch, all of whom we will meet across the chapters of this book.

We’ll be looking at how patriarchy has used images of women to contain and limit them, and how these archetypes persist in our contemporary culture, shaping our ideas of not only beauty and taste, but also national identity, political authority, sexuality and our deepest fears and expectations about what it means to be human. After all, historical images have lives and histories that go beyond the context of their creation. While not everyone goes to Western art galleries, more or less everyone living in the developed world is caught in the unescapable capitalist slipstream of advertising and social media – where historical images of women contour and inform popular culture, from music videos, to advertising for formula milk, to album covers and fashion photography. Some media reference this legacy explicitly, from Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s music video for ‘Apeshit’, shot in the Louvre; to Reebok ads ripping off Renaissance artist Botticelli to sell sportswear; to fashion and lifestyle shoots inspired by the horizontal or docile women in our art collections. Many more are influenced tacitly as our heritage of fine art and cultural images becomes part of our shared visual language. And, as we have seen in the National Gallery’s collection, many of these images objectify women, normalise violence against them, stereotype or exclude racial diversity, or demonise ageing and non-normative bodies and sexualities.

We’ll also be looking at how women artists have challenged these scripts with images that expose culture’s misogynistic legacy and help us to rethink the value of women’s work and the politics of their pleasure, sexuality and power.

Wherever we find them, pictures are not neutral; they can be pernicious and powerful. They help us to form attitudes towards ourselves and others, and sustain our understanding of history, culture, race and sexual identity, among many other things. Most of this power is silent and stealthy, sold to us under the guise of leisure, or an appreciation of beauty and achievement.

Art history has a reputation for being elitist and often irrelevant, and certainly a stereotype of the suited and booted (generally white male) art connoisseur offering judgements about virtuosity and taste has been sold to us in popular TV art history programmes. But art history offers us so much more than luxury connoisseurship for the leisured classes, or background knowledge to inform cultural visits on holiday between wine tasting and artisan shopping trips. Art history can help us see how everyday images of women are steeped in ideas about body shame, how Renaissance paintings can start conversations about rape culture, how pictures of the classical monster Medusa relate to white nationalism and supremacy, or how lifestyle blogs promote the same ideas of wifely virtue as Golden-Age Dutch paintings.

I’m certainly not the first person to raise this. Feminist scholars have been calling out the cultural ramifications of misogyny for half a century. Some of these ideas have also entered mainstream discussions: for example, the concept of the ‘male gaze’, which is the idea that most images, films, plays and works of culture are produced for the pleasure and satisfaction of an implied male spectator; or the concept of ‘sexual objectification’, which is the presentation of someone not as a complex human being but one whose worth is based on their sexual attractiveness to the person looking at them.

Some 40 years ago the American art historian Linda Nochlin wrote the now famous essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, which broached the institutional exclusion of women as artists but also asked us to reconsider the glorifying category of ‘greatness’ that is given to some (generally white male) art and artists in the first place.

There have since been numerous projects to recuperate the absent women from our art collections and correct the historical archives that overlooked them. One early example was the 1972 exhibition ‘Old Mistresses’ curated by Elizabeth Broun and Ann Gabhart, a title that exposes how the language we use in discussing art and artists is heavily biased according to gender. While the term ‘Old Master’ communicates status, value and an accepted place in the canon of esteemed art for well-known artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci or Rembrandt, there is no equivalent term to describe women artists from similar periods. The word ‘mistress’ holds altogether different and sexual connotations.3

Throughout this book I use the term ‘woman artist’, but it’s worth mentioning what is at stake in using this: the gendered distinction enforces the idea that the default identity of an artist is male, and that women artists are a subversive anomaly. (We have, for instance, dropped the terms ‘lady surgeon’ or ‘lady judge’ that do a similar job in undermining women’s professional status.) You might instead choose to adopt art historian Griselda Pollock’s suggestion of ‘artist-woman’ where it’s relevant to note gender.

While many continuing efforts are devoted to making women’s contributions to culture more visible, for example with new books and exhibitions, it’s also vital to also consider why this is so important, particularly when it comes to making pictures. Since 1985, a group of anonymous women artist-activists known as the Guerrilla Girls have been calling out gender and racial disparity in the works that line the walls of our museums and institutions. In a poster from 1989 they make the obvious case for why we should care about this marginalisation: ‘You’re seeing less than half the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of color.’

These critical voices have not exclusively belonged to feminist art historians and artists. Cultural and literary critic John Berger’s book Ways of Seeing, first published in 1972, has sold over a million copies and has never gone out of print. Berger was the first to set up a framework for seeing how images in everyday life, such as photographs and advertising, echoed traditional and much valued images of European art. Moreover, he showed us how seeing this clearly could open up illuminating discussions about the politics of looking itself.

Guerrilla Girls, You’re Seeing Less Than Half the Picture, 1989, Tate, London. © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

His iconic aphorism that in the history of painting ‘men act, women appear’ neatly sums up the gendered power dynamic that women have been depicted for how they look rather than how they see. Then there was his take on the real-world impact of the male gaze on women’s lives: that a woman ‘has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life’.

Despite the legacies of these ideas in academia, in the mainstream, discussions of how women are seen and how they see keep getting lost. It is knowledge that tends to keep getting obscured as too specialist, too academic, too radical (too annoying) for a general audience, and this is where I hope this book will come in useful because the conversation about women, art and women’s art is far from closed. Public discussion of pictures of women’s bodies continues to stoke inflamed debates. Late in 2017 thousands of people signed a petition asking curators to change the context of a painting hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The painting in question, called Thérèse Dreaming, is a voyeuristic depiction of a twelve-year-old girl, her eyes closed in pleasant reverie with her arms behind her head. It was painted by the controversial French-Polish artist Balthus in 1938, a man who throughout his career regularly had girls as young as eight take off their clothes and sit for him in his studio.

In the painting the girl’s legs are splayed and one rests on the stool in front of her to give a view of the white gusset of her knickers. In the foreground a cat laps at a saucer of milk. If we were to discuss the image along the lines of ‘how to read a picture’, we might say that her raised knee makes the top of an axis that continues with the white gusset covering her crotch and culminates in the cat’s head delicately supping at a saucer of milk (also white) directly below. The arrangement makes no ambiguity in suggesting what the external manifestation of her daydream is.

The petition called not for the removal of the work but an acknowledgement that the painting was an eroticised depiction of a child by an adult, and moreover an adult who had a controversial reputation that drew parallels in his time with the fictional character Humbert Humbert from Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Lolita – a man with a sexual passion for young girls. (Throughout his career Balthus repeatedly denied any erotic intention on his part, suggesting instead that any sexual inferences were down to the viewer’s projected perversions.)

The petition and media coverage opened up many thorny issues. Voices of the art establishment clamoured to suggest that sexual experience, especially the nascent desires of children on the threshold of sexual activity, is a valid motif for art to explore because, although uncomfortable, it is a fact of the human condition and therefore art’s role to document and explore it. But the difficulty remains in who precisely is doing this exploring. Balthus’ painting is not an individual’s own expression of their privately burgeoning sexuality – it is an adult male’s adaptation of a child’s sexual inner life.

While some saw the request as a violent puritanical clampdown on human desire, others highlighted a hypocrisy in society’s criminalisation of paedophilia but tacit romanticisation of it in Balthus’ work, seeing it as an example of the widespread sexualisation of young women – not least in the midst of the Me Too movement that had recently erupted.

The Met refused either to take down the work or alter the wall text to acknowledge any allusions to sex between an adult and a minor, and lots of smug articles were written – by male and female authors – suggesting ultimately that these voices of opposition just didn’t get what ‘real art’ was. The inflections were subtle, but the condescension was there in referring to Ms Merrill, the originator of the petition, as ‘an HR manager’ and therefore an outsider to the art cognoscenti, unqualified to voice what she and over 11,000 other people felt when standing in front of Balthus’ painting.

A matter of weeks later, a similar discussion about censorship and women’s bodies erupted over a curatorial intervention at the Manchester Art Gallery in the UK. After discussions and research with gallery staff, curator Clare Gannaway and artist Sonia Boyce discovered that many women within the institution had opinions about how gender was represented in the images hanging on the gallery walls – in particular the way in which women tended to be depicted either as ‘femme fatales or as passive figures of beauty’, especially in a climate where the exploitation and sexualisation of women was dominating public discussions.

Boyce decided to create a space on the gallery walls where this conversation could be aired, as a way of asking questions about power and taste and who gets to decide what story of culture we are offered by our cultural gatekeepers. John William Waterhouse’s painting Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) was taken out of the ‘In Pursuit of Beauty’ gallery for a week, leaving a blank space where it had hung for gallery visitors to post comments on yellow sticky notes. This was part of a series of ‘interventions’ that aimed to look at the Manchester Art Gallery collection from a more contemporary perspective.

The painting is a Victorian fantasy of an episode from classical poetry in which the young Hylas, the male lover of Heracles, is lured to his death by a group of bare-breasted long-haired water nymphs who pull him underwater. It is a classic example of the Victorian era’s fascination with the imaginary figure of the sexually enticing yet villainous ‘femme fatale’.

The intervention provoked another row of mixed opinions in the press, and plenty of umbrage vented on Twitter. Right-wing voices tweeted: ‘why is a curator for fake contemporary “art” allowed to interfere with real art like Hylas and the Nymphs in the first place??’ Others were quick to underline that the women and not Hylas were pictured in a predatory role, and others yet cried about the dangers of censorship and compared feminists to ISIS. One of the many responses on the discussion board of the gallery’s website stated that: ‘provoking discussion through this is just dangerous.’

As the gallery lost control of the discussion and it spiralled online, what failed to be duly noted was that in a room devoted to the ‘Pursuit of Beauty’, only one type of beauty was represented – youthful and white. Misinterpreted almost unanimously as an act of puritanical ‘censorship’, what was also missing from the furore over Boyce’s intervention was that Hylas and the Nymphs (like Balthus’ Thérèse Dreaming) is a man’s version of what adolescent female beauty and sexuality should look like – that is pert and attractive and objectified. Even more importantly, Waterhouse’s painting is not something that celebrates young women’s sexuality but instead casts it in a negative light, as something dangerous and malevolent. This idea has fed into real-life attitudes towards young women’s bodies and continues to do so, and, to my mind at least, it is far more ‘dangerous’ than any questions of censorship.

The fact that artist Sonia Boyce, as a woman of colour, should challenge this singular white male view of beauty and sexuality inspired a violent urge to protect it as sacrosanct and inviolable. Her intervention then was not about banning certain depictions of women in paintings, neither was it only about questioning sexualised depictions of adolescents; it instead revealed how deeply images touch us and affect us, how violently we rush to defend them, and how they shape our lives for better and for worse.

What both incidents at the Met and the Manchester Art Gallery have made clear is that the meanings of collections, images and artworks are not static but fluctuate according to the rush of the outside world. In recent years racial justice movements and feminism’s fourth wave have made us look around at what we have taken for granted as normal or everyday. Sculptures that have existed for decades or centuries celebrating colonial or imperial violence have been toppled. New sculptures have been put contentiously in place. Advertising images that demean people of colour have been pulled (such as Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben). Meanings of works of art or film that we have loved and grown up with have been revisited, their politics questioned, the values – about race, about women’s bodies – that they promote re-examined. Art museums and galleries have been compelled to address whose stories they celebrate and show on their walls, as they seek to rebalance the exclusion of women and people of colour from the version of culture they promote as historical truth.

The overwhelming popular response to these discussions also confirms that the art of the past must be freed from privileged knowledge and made able to speak to lived experience in the now. Art and culture are not separate to our discussions about the politics of gender, race and representation; they are at its very heart.

I’m going to be asking you to look again at well-known images, but to look at them ‘slant’, approaching from a different perspective to see how they might cast light on the discussions we are having about women and women’s bodies today.

With all this in mind, we’re going to start with Venus – the mythological goddess of love, beauty and sex – who we’ve been led to believe represents the icon of womanhood itself, but whose body is something of a battleground on which discussions of shame, desire, race and sex play out.

Venus

Room 30 of the National Gallery in London is like a giant jewellery box, a grand hall lined with crimson damask. On its walls hangs a collection of seventeenth-century Spanish ‘masterpieces’. There is one naked body in the room. It’s a young woman’s, reclining with her back to us, fully nude on a bed whose covers are agitated with the promise of sex. The ripples of silk and cotton echo the curves of her body. Her waist is impossibly small, her buttocks smooth and peachy, and her skin pearlescent, free from blemish, bruise or hair. Spectators ebb and flow to gaze at her body, seemingly unperturbed by their voyeurism. She doesn’t seem bothered either. A pot-bellied toddler with wings props up a mirror in front of her and on its charred surface you can just see her face, looking back at us, as we look at her body. She isn’t smiling, or scowling. She doesn’t look scared or anxious – or even surprised. She’s just seeing you looking at her, and she knows that’s the way it goes. After all, she has been here a long time. Gallery visitors amble past, the word ‘beautiful’ dropping casually from their lips and amateur artists copy her curves. Images of illustrious men surround her. Like sentinels, they flank her – one an archbishop, one a king. Do they guard her or own her? It’s hard to tell.