Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

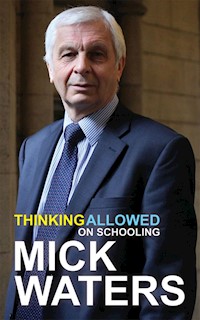

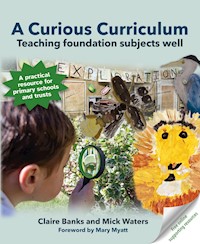

Written by Claire Banks and Mick Waters, A Curious Curriculum: Teaching foundation subjects well details the insightful and transformational steps that a school can take towards designing and delivering a rich, rigorous and wide-ranging curriculum. Foreword by Mary Myatt. Rather than being a model curriculum that can be uprooted and planted in any school, the book is a model schools can use to design their own curriculum, one that not only encourages children to be active participants in their own learning, but also to see the benefits of being part of a bigger, wider family of learners. The authors concentrate on the foundation subjects, particularly history, geography and science but also design and technology (DT) and art and design areas that are often challenging for teachers in primary schools. Subjects are brought together and explored under "big ideas" and, crucially, the emphasis is on avoiding the superficial and trivial and rooting teaching in extending and challenging children. In A Curious Curriculum, Claire Banks and Mick Waters share the story of one multi-academy trust (MAT) which designed and delivered a shared educational vision, a rationale for excellence in the curriculum, and the resources and support given to help reduce teachers' workload. Claire and Mick present a clear model both for supporting a group of schools or leading one school, offering a fresh perspective on working on a MAT-wide curriculum, as well as providing a range of snapshot examples of the curriculum in action in the form of documents, plans, photos and the learners' own work. The book shares transferrable lessons from the trust's journey to success, setting out an educational philosophy that pairs pedagogy with a well-structured curriculum designed with learners' best interests at its heart. All children deserve an engaging, exciting curriculum designed to spark their curiosity, feed their imagination and develop their skills and knowledge. With clear timelines and an honest and transparent dialogue about the challenges and benefits of working together collaboratively and the importance of external expertise, A Curious Curriculum is an essential read for all school leaders. Suitable for executive leaders, head teachers, curriculum coordinators and subject leaders in primary school settings.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 445

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A

Praise for A Curious Curriculum

This is a powerful, hard-hitting book about how we ensure that the curriculum truly inspires curiosity and challenge in primary-aged learners. Alongside beautiful illustrations and inspiring stories of practice, there is a strong undercurrent that cuts across complacency. With dialogic pedagogy at the heart, this text seeks to explore how the highest standards can be achieved within and through foundation subjects – standards that can never be achieved via formulaic lessons. The authentic wisdom of these authors really packs a punch. Not to be missed.

Dame Alison Peacock, DL, Chief Executive, Chartered College of Teaching

An intelligent, honest and practical account of a multi-academy trust’s journey to create an authentically rich and progressive curriculum. Claire Banks and Mick Waters present a compelling vision for a preferred future for primary school provision.

Kevin Butlin, Director of Education, Plymouth CAST Multi-Academy Trust

A Curious Curriculum is likely to be an enormous asset to all in primary who (using the authors’ own words) seek to be ‘well informed, well read and thoughtfully discerning … careful to distinguish between trends, fads and genuine new answers to perennial questions’ in relation to the curriculum. This approach is to be admired for the whole curriculum and in particular for foundation subjects – which are so often the poor relative. I particularly like that the whole process of collaboratively applying this approach to create a truly owned curious curriculum that has both depth and breadth is analysed in a way that does not claim to create a model that can be ‘lifted and shifted’ into different contexts. Rather, what arises from the analysis is a set of principles and ways of working that can be applied and owned in a range of ways.

Professor Sam Twiselton, OBE, Director of Sheffield Institute of Education, Sheffield Hallam University

The focus on curriculum development and its position at the core of school improvement is one of the golden threads of what makes for a strong and sustainable trust. When a trust is set up, it is done so with the core aim of creating better educational opportunities for children than were possible before. That was the deal! This brilliant book, from a trust I know well and have huge respect for, traces the development of curriculum thinking from the perspective of the trust, seen through the eyes of the schools. This book does not tell people what to include in a curriculum. Why would it? Instead, it is a case study in leading change. How to take people with you. How to communicate intent. How to create expectations of what will happen in different classrooms where the ownership of the trust curriculum is with the teacher and not the trust itself. The more our most credible practitioners can share with the wider sector, the better. This book adds to the growing library of must-read books. I loved it.

Sir David Carter, former National Schools Commissioner, Director of Carter Leadership Consultancy

There is so much in this book that I wish I had written, and even more that I am glad I have read. I will go back to it again and again and will look forward to every visit.

David Cameron, The Real David Cameron Ltd

This compelling narrative unveils the journey of a collaborative endeavour that is steeped in a commitment to an ecology of learning and flourishing. Claire and Mick provide an honest and insightful account of how the trust has been able to foster and nurture a curriculum that provides an equity of provision and opportunity for all children. With practical tips and key questions underpinned by an informed and inspired philosophy of education, this book is a crucial read for all pragmatic educators who are interested in planning for the unpredictable and cultivating joy.

Vikki Pendry, CEO, The Curriculum Foundation

A Curious Curriculum doesn’t offer an off-the-shelf solution (although QR codes link directly to resources for readers), but rather a lively buffet of what a curriculum could be – for those brave enough, and curious enough, to try.

Judith Schafer, Director, One Cumbria Teaching School Hub

A really interesting read that will help schools navigating their important journey in developing and evaluating their curriculum. It highlights the importance of the thought behind individual curriculums and provides a structured way to reach the desired outcome, learning from this trust’s experience.

Mrs J. Heaton, OBE, CEO, Northern Lights Learning TrustB

Crafting a school curriculum that is rich in engaging learning experiences should be a priority for every school, yet it is a complex task fraught with challenges. A Curious Curriculum describes the journey undertaken by a school trust to bring teaching communities together to construct the foundations of a school curriculum that is engaging, motivational and wholly relevant to the present and future world in which our young people live. At the same time, it provides other schools with a framework to allow them to reflect on their own practice and inspires them with practical tools to reimagine a school curriculum that places high-quality learning at its heart. Thank you, Claire and Mick, for a compelling and uplifting read that will benefit educators around the world.

Daniel Jones, Chief Education Officer, Globeducate

Refreshing in its honesty and humility, A Curious Curriculum is a comprehensive resource for any school or trust leader looking to improve their curriculum. Rightly proud of Olympus Trust’s curious curriculum, the authors nevertheless do not present it as a blueprint for others to follow, rather as evidence of the depth of thinking and planning that characterise their approach to the foundation subjects. The real value of this book is in how it describes one trust’s journey in navigating the snakes and ladders of curriculum development. Readers are invited not to ‘drag and drop’ the curious curriculum developed at Olympus, but to learn from how it was done, what worked and what was difficult. It was a joy and an education to see beneath the bonnet of such a considered and coherent approach to curriculum.

Dr Kate Chhatwal, OBE, Chief Executive, Challenge Partners

I encourage all educators to read this book! Filled with a sense of joy, it has put learning at the centre for all. It will empower you to wonder, explore and become forward-thinking leaders. This book exemplifies the journey of a trust that has understood that if you want innovative learners, you need innovative educators/facilitators. Ultimately, innovation is not about a skill set, it’s about a mindset, and to develop this mindset takes planning, sampling and, most importantly, talking about learning. Claire and Mick guide the way with great models, questions and exemplars that will help any educator to critically assess where they are on the journey. I am left with the curiosity to take a deeper look at the curriculum models in our trust. I particularly love how the development takes into consideration how the curriculum will be experienced by the child by using ‘through the eyes of the child’ in the planning.

Sarah Finch, CEO, Marches Academy Trust

Wherever you are on your curriculum journey, I highly recommend this book. Through the eyes of the children, it charts the long-term journey Olympus Trust has taken to ensure that the foundation subjects are taught as well as English and maths. It provides a practical walkthrough with real examples of their rich and engaging process, reminding us of the importance of sharing the ‘why’ behind all decision-making. This is not an off-the-shelf answer for your curriculum. It will inspire you to think and have rich discussions about how your curriculum and pedagogy are interwoven to ensure children are equipped with the best opportunities to flourish and thrive.

Narinder Gill, School Improvement Director, Elevate Multi-Academy Trust, author of Creating Change in Urban Settings

The Curious Curriculum is a must-read for anyone with a passion for a values-driven, child-centred approach to teaching and learning. Claire and Mick brilliantly articulate the interconnection between a philosophy of education, inclusive pedagogical principles and deep subject knowledge. Claire and Mick place great sensitivity on the context of individual schools and the autonomy of practitioners.

Claire Shaw, Diocesan Director of Education

This is so much more than a book on developing a great foundation curriculum! It is a book about effective change management, about leadership behaviours, culture and practice, underpinned by an honest narrative sharing all the benefits of hindsight. The ‘through the eyes of the child’ perspective reminds us all that we should never get distracted from this. I feel inspired!

Mrs Claire Savory, Director of Academies, Gloucestershire Learning Alliance

C

A Curious Curriculum

Teaching foundation subjects well

Claire Banks and Mick Waters

This book is an appreciation of the professionalism and commitment of head teachers and the community of schools in the Olympus Academy Trust. Their efforts have enriched learning and enhanced the life chances of children in our schools.

F

Foreword

It is odd that in some quarters there is talk about the curriculum as though it is a ‘new thing’. Yet, there has always been a curriculum, even before the national curriculum, and even before it became a focus in the quality of education judgement in the latest inspection framework. What is new, however, is the attention being paid to the quality of what is being offered to pupils, particularly in the foundation subjects. While English and mathematics have been well served in terms of resources, thinking and planning – and with good reason – the same cannot be said for the other subjects. What has characterised the planning and delivery of the foundation subjects in many, but not all, parts of the sector, is that they are something to be ‘covered’, in the form of activities for pupils to do rather than worthwhile areas of exploration.

The reasons for the foundation subjects being poor relations in terms of curriculum thinking and realisation are understandable: pressures of time, absence of resources and lack of knowledge about where to find good materials. But, with the sector now focused on levelling up the wider curriculum beyond the core, many of us have realised that this is about more than tarting up plans or refreshing a bought-in scheme. It is more complicated than that, and there is work to be done over the long term.ii

We talk about making sure the curriculum is coherent for our pupils, but is our approach to thinking about and planning that curriculum also coherent? Is there a shared meaning beyond the catchy headlines? If we are going to get better at this, we need to begin by taking a wider view and looking at and interrogating examples from other contexts. A Curious Curriculum provides a missing link in the literature on how to make this aspect of school provision actually work on the ground.

We might have all the values statements in the world, but are we doing the gritty work of making sure that the curriculum is working for every child, every day, in every classroom? It is never a blame game, but why is it so common to find that schools are downloading generic stand-alone lesson plans and then wondering why the pupils don’t know, aren’t able to talk about or do something with what they have been given? This is because we have often slipped into a hand-to-mouth approach, as Banks and Waters call it, to curriculum delivery. In these cases, it means that the provision of a task or an activity becomes more important than whether the pupils have learned anything.

It struck me as I read this book that the three categories of student teachers identified by Professor Sam Twiselton1 might be applied to curriculum leadership: task managers who view their main role as being very product orientated, concerned with completing the task rather than developing the learning; curriculum deliverers, where there is more explicit reference to learning, but this is conceived within the restrictions of an externally given curriculum and where curriculum coverage frequently trumps learning; and, finally, concept and skill builders, where there is a focus on proficiency and deep learning. iii

What we have in this terrific book is the account of one trust setting out to think about, talk about and attempt to realise what an honest, ambitious provision might look like. At Olympus Academy, a cross-phase trust with eleven schools, this work is led by Claire Banks, director of education, with support from Professor Mick Waters (lucky them). It is full of provocations and bold statements, which help us to move from task managers to concept and skill builders. The authors explain how the trust has answered these questions, why they established ‘narrative’ curriculum plans, which is a genius idea, and give us examples of what this looks like in their context. It is this concrete, exemplar work that will be a real boon to the profession.

There are several important threads in A Curious Curriculum. One relates to reappraising what counts as valuable work: when presented with the ‘products’ of pupils’ learning, can we really say that they have learned something when all they have done is fill in the gaps or coloured a worksheet, when instead they might be presenting at an exhibition?

Another notable thread is a proper focus on the curriculum as it is experienced through the eyes of a child. We are likely to know that we are on the right track if we hear pupils talking about their work being complicated, that what they are learning is making them wonder and that the questions help them to understand bigger, wider ideas.

A further thread is that this sort of work is fundamentally about problem-solving: solving problems is complex and occasionally frustrating but also exhilarating when things go well. This is much more rewarding than the pursuit of silver bullets and quick fixes.

To shift the perspective from ‘What am I doing as a teacher?’ to ‘What are my pupils learning?’ needs sensitive and purposeful engagement to get to the heart of the matter. In A Curious Curriculum, Banks and Waters describe how they went about this: the setbacks, the insights, the doubts and, above all, the growing ownership by all involved ivin this important work. We need to stop thinking that this element of provision can be completed quickly. It can’t. It is slow, deliberate, purposeful work, and it will always be work in progress. What the authors have also shown in this book is that it can also be great fun!

Mary Myatt

1 S. Twiselton, V. Randall and S. Lane, Developing Effective Teachers: Perspectives and Approaches, Impact: Journal of the Chartered College of Teaching (summer 2018). Available at: https://my.chartered.college/impact_article/developing-effective-teachers-perspectives-and-approaches.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Claire Banks and Mick Waters may have written this book but they have simply told the story. In truth, the story has been written by the teachers and children in our schools, supported by colleagues within Olympus Academy Trust. As with all organisations, some of the head teachers and teachers have moved elsewhere and some are newer to our community. Their names may only be listed here but their contribution to our book is significant.

Bradley Stoke Community School: Sharon Clark, head of primary phase, working with Vicky Williams and Natasha Beech as curriculum leads.Callicroft Primary Academy: Lucy Lang, head teacher, working with Camilla Oscroft as deputy head and Rachel Wagstaff as curriculum lead. Richard Clark was the previous head teacher who retired in April 2022.Charborough Road Primary School: Matt Lankester, head teacher, working with Claire Jones as deputy head and James Davolls, early years lead.Filton Hill Primary School: Ian Oake, head teacher, working with Sara Malik, deputy head, and Emma Escott, curriculum lead. Kirsten Lemming was the previous head teacher who retired in August 2021.Meadowbrook Primary School: Nicola Bailey, head teacher, working alongside Laura Walker as deputy head and curriculum lead.Stoke Lodge Primary School: Will Ferris, head teacher, working alongside Sarah Reeves as deputy head and curriculum lead.Dave Baker: CEO, Olympus Academy Trust.viSarah Gardner: executive assistant, Olympus Academy Trust.Kate Sheldon: trustee, Olympus Academy Trust.Richard Sloan: previous chair of trustees, Olympus Academy Trust.Jen Wathan: teaching and learning lead, Olympus Academy Trust.Sarah Williams: chair of trustees, Olympus Academy Trust.We owe a huge debt to those who have helped us to bring this book to the reader. As well as the contributors listed above, we would like to thank Mary Myatt, an accomplished author and recognised authority on curriculum practice in schools, for offering to write our foreword. Alistair Bryce-Clegg’s work has informed our parallel work in the early years phase, and Rob Carpenter at Inspire Partnership supported our early enquiries into development. We are grateful for the assistance of Patrice Baldwin, chair of the Council for Subject Associations.

The graphic work in our trust publications, and much of it in the book, has been developed by Rob Wilson from FortyFour Creative. Many of the photographs in the book and on the accompanying web platform have been produced by Richard Clark, Blue Apple Education and Richard McDonough. Jen Wathan has, as always, been a valued support to us in the work we have done with schools, as well as helping us to collate examples of illustrative material. We are indebted to Amarjot Butcher who has helped us with the organisation and management of producing the book. Lastly, the team at Crown House has been a source of support and advice throughout, particularly our editors, Daniel Bowen and Emma Tuck. We are grateful to them all.

CONTENTS

xvi

Introduction: a curriculum built on a good foundation

Why we have written this book

We want to help teachers enjoy teaching some of the foundation subjects well, and, in doing so, see children in primary schools become intrigued by their world and set on a path to success in school and beyond. Knowing that schools grapple with the challenge of curriculum design and the teaching that accompanies it, we wanted to share our experience of developing foundation subjects in the hope that a description of our work and the thinking behind it would be of use to schools elsewhere. This is a book that tries to support head teachers and curriculum coordinators by showing practice, exploring the thinking behind it and describing the process of securing consistent benefits for all children. It tells the story of the development of entwined curriculum and pedagogy in some of the foundation subjects.

Over the course of five years, we have worked together with a group of head teachers, teachers and teaching assistants to help them make a positive difference to children’s learning experiences. The schools involved are now proud of their professional work in this area. We know that every school sets out to teach well and ensure good learning outcomes for its children. Every school also sets out at some point to define, reshape and redefine its curriculum. In this 2book, we explore how our schools have managed to both design an appropriate curriculum and teach it.

Children experience and enjoy the learning we plan. In our schools, it is provided as a Curious Curriculum. Both of these words have Latin roots. Curriculum means ‘course’, in the sense of a route to be followed. We also wanted our children to build their sense of being eager to learn and know – the Latin meaning for the word ‘curious’. Curriculum also means ‘speculation or intent’ – our ambitions. Our Curious Curriculum is a course that leads children to the learning ambitions we have for them.

Who we are and how this story began

Five years ago, Claire had recently been appointed to support the work of all primary schools in the Olympus Academy Trust to the benefit of every child. She had many years of experience as a head teacher in an inner-city primary school in Bristol and was building working relationships with the schools in the trust: the head teachers, teaching and other staff, children and wider communities. A common thread for all the schools was concern about the effectiveness of curriculum, partly as a result of revision of the national curriculum in 20131 and partly due to the natural commitment of most staff in primary schools to enjoy the best of learning with and for children.

The community of head teachers signed up to a programme of curriculum development to unfold over the next year or two. Claire decided that it would be useful to have some advice and support from a source external to the trust and turned to Mick.

Mick had been around the educational block a few times in various roles from schools to local authority to a national role as director of 3curriculum at the then Qualifications and Curriculum Authority. Mick’s experience in supporting schools in different parts of the country and beyond had been utilised by Claire in her previous school, and she asked him again to lead an initial staff development day about the curriculum at the start of a school year, followed by intermittent school-based support over the course of the next twelve months. At the time, Mick remarked that it would take longer than that, and they discussed the premise that curriculum has to be linked with pedagogy to make progress.

Mick has spent about ten days a year supporting the trust, working in schools, contributing to their conferences and workshops, and doing detailed work with head teachers or curriculum lead groups. His role has been to provide the necessary spur, to throw a new pebble in the pond, to hold a mirror up to what was being achieved. Over the five years we describe, Mick spent a total of about thirty days with the schools prior to the COVID-19 lockdowns, supplemented by time spent producing documents, being in touch and talking on the phone to Claire. During lockdown he Zoomed in periodically.

Where Mick has floated in, Claire has been submerged, helping the schools to develop on a day-by-day basis. Naturally, there is the ongoing big agenda linked to supporting schools in seeking continuous improvement, checking progress, helping with all manner of urgencies, and looking after individuals and schools when problems crop up – the agenda that anyone in a leadership position would recognise. Alongside this, she has also done the hard bits: supporting people’s efforts, reminding them of agreements, checking understanding, organising meetings, insisting that things get done, confronting occasional shortcomings, and endlessly recognising effort and achievement.

Although Claire and Mick have an unbalanced partnership, both agree that the crucial work in developing our curriculum story 4successfully has been done by the teachers, teaching assistants and head teachers day after day in the schools. Nothing that has been achieved could have been achieved without their commitment and willingness to keep pushing the boundaries of practice. At times it has been exhilarating, at times frustrating and at times sheer graft. What it has been is a story of continuous improvement, children’s achievement and professional worth.

What this book tries to do

A book can only ever accomplish so much. There are libraries of books on curriculum theory and rationale. This is a book about some of the foundation subjects – those subjects that primary schools often teach through a themed or topic approach. Much of the focus is on the teaching of history, geography and science, of which there has been much consideration about where knowledge fits in; there is less specific reference to music or PE. We have also covered design and technology (DT) and art and design, two areas that are often challenging for teachers in primary schools.

As the book is about the foundation subjects, it addresses the prospect of organising learning into themes that bring the subject disciplines together under ‘big ideas’. But it is not a book that rejects the discrete teaching of some aspects of some subject disciplines. Nor do we shy away from giving examples of where mathematics and English can be strengthened through good work in foundation subjects or used to strengthen the wider subject knowledge of the children. As Mary Myatt comments, we are not a trust that has sidelined the wider curriculum;2 indeed, this book is about exactly the opposite. We stress that our teaching must avoid the superficial and trivial and must be rooted in extending and challenging children. 5

This is a book about how we can teach some aspects of the broader curriculum and do it at depth – and teach it well.

Many books deal with curriculum design by relating curriculum theory to the content that schools need to include, through requirement or philosophy. Other books offer schools a curriculum plan to ensure coverage and depth. Yet more books explore pedagogy or assessment. Our book tries to explain how we made decisions on the ‘what’ of curriculum and then ensured that everyone understood the reasons for those decisions – the ‘why’ of the work we do. This is vital for the adults in the school, of course, but also for the parents and, most importantly, the children.

We then go on to set out some of the tactics we have used to overcome challenges and make successes become routine. Part Two is almost a collection of insights, linked to research, which would support consideration of many aspects of school leadership. We take the general principles and explore how schools can make them work in their own circumstances.

We needed our staff to make the curriculum their own. We wanted teachers to commit to a curriculum for their children – a curriculum that mattered for their community rather than one that was simply packaged for them to deliver. What we call our Curious Curriculum is work in progress, and always will be. That is the thing about learning and teaching: we should keep exploring new territory and pushing the boundaries in the quest for continuous improvement.

We deal with both the big picture and the detail, addressing intellectual concepts and how they are best explored, and delve into the ways that teachers can organise and manage specific and detailed aspects of classroom life to ensure success. At times, we focus on global issues that affect our world today and our children’s futures, such as sustainability, economy, identity and technology. At other times, we find ourselves discussing how to help children to fold paper, use scissors or mix paint.6

This book is essentially our own dialogue about the development of the Curious Curriculum – how we approached the work and how we got it done. It is not a model curriculum that can be uprooted and planted in any school, but we hope that the discussions, explanations, assertions, asides and advice will resonate with you as you relate the circumstances to your own school setting. We have spent many hours over the last five years discussing the complicated world that is the school and the best way to enable those closest to the children to take another step towards the effectiveness that every teacher wants to feel.

This is not a ‘certain’ book with a straightforward solution or a ‘must do’ sequence of actions. We offer our experience with professional humility, inviting readers to use what makes sense for your own school at the time you need it. We both learned long ago that the application of a formula is rarely effective in teaching.

Because we do not believe in off-the-shelf solutions, we have not included our whole curriculum plan, but we have included many sections to exemplify what we do cover.

This book paints a picture of how we developed the Curious Curriculum over time and, importantly, how it will continue to develop. We all know that curriculum doesn’t stand still. It evolves and adjusts to new developments in thinking and research, to new understandings about learning, and to our own growing professional competence and confidence.

We wanted everyone involved to engage deeply rather than be expected to ‘deliver’. We wanted them to exercise responsibility over the work they do, collaborate over curriculum design and innovate to push the boundaries of pedagogy. We wanted them to be professionally curious about just how good learning could be and aim for excellence.7

Why investing in our teachers and other staff matters

The story of curriculum is paved with good intentions. So many nations, schools and teachers set out to provide coherent teaching with good learning outcomes, and then find a gap between the planned curriculum and what the child experiences.

The first challenge facing schools is to make sense of the many and competing demands in terms of what children should be taught. In England, on top of a national curriculum (which, of course, is not required of academies) and guidance from government sits a whole range of imperatives: some are local expectations, some are traditional to the school, some are interpretations of the accountability framework and some are aspects that are ‘on message’ at the time. Often, when schools have organised all this into policies and charts, they breathe a sigh of relief – until next time. There is an intrinsic fascination with trying to sort out learning journeys for children, coupled with a recognisable frustration that outcomes often fall short of managerial expectations.

The second challenge schools face is how to interpret curriculum expectations in terms of how they are taught. The recognition that variability within schools is a key problem has led to leaders being urged to secure consistency, which in turn has brought about many of the compliance-focused developments of recent years. Performance management and target-setting have resulted in lesson observations and the emergence of ‘good lesson’ templates to ensure that teachers include the essential features.

More recently, some trusts and schools have started to provide scripted lessons, quality assured by leadership. The main problem with a scripted lesson, of course, is that the children need to know the script or there is a risk that the lesson will go off course. The same blueprint was behind the provision of textbooks and workbooks fifty years ago.8

They were eventually phased out because the professionalism of the teacher was being factored out and learning would not work in the same way for all aspects of a subject discipline. The other reason textbooks faded away is that children vary so much that the blueprint very quickly fails to work with a significant proportion, and the teacher is left grappling with a different problem. It is vital, therefore, that teachers understand fully the thinking behind the curriculum they provide and learn how to make it work with all their learners.

All of this has now come into sharp relief because the inspection framework has changed to include a focus on the curriculum.3 This is not a book about how to keep inspectors happy, although inspectors have been very positive about developments in the trust’s schools in respect of the Curious Curriculum. This book is built on first principles – of doing right by every child – on the premise that accountability begins there.

The curriculum comes alive at the point when it meets the child. It is only then that it informs, clarifies, reassures, intrigues and amazes as it unveils new areas of learning and builds on what is already in place. Until that point, the curriculum is an abstract; it is what the government or the school expects all children to be offered.

We have written this book jointly, so you might detect differences in style at times. Some of our writing is business-like and functional. At times, there is a narrative describing a series of steps or events. At other times, the writing is lyrical or quizzical. This reflects the sorts of dialogues we have had over time as we have grappled with our developing agenda. We have organised, managed, structured and recorded our development, and we have puzzled, wondered, researched and laughed. We hope this is reflected in our writing. 9

This book tells our story. You might want to dwell on some parts and dig into the detail. We visit some points more than once in different contexts because that is what teaching is like. We have alluded to research and background reading that you may wish to explore further. You might want to delve into our connected website (www.crownhouse.co.uk/curious-curriculum), using the QR codes, and explore some of our resources as a stimulus for your own work. We have included some photographs, though anyone in a school will understand the need for caution around images of children. It is not an instruction manual. We would love you to be curious, to be fascinated by learning and to be stimulated by the professional excitement of seeing children truly engage with it. We hope that you enjoy our Curious Curriculum adventure – and then enjoy your own.

Is the Curious Curriculum based on a particular theory?

Our curriculum development takes account of theoretical perspectives but, crucially, it is not wedded to any particular school of thought. Theoretical perspectives evolve over time as they are informed and influenced by research.

Our starting point is to be well informed, well read and thoughtfully discerning. We are careful to distinguish between trends, fads and genuine new answers to perennial questions. Too often, novel approaches sweep through schooling based on new rhetoric and become dogma and unquestioned practice. Both of us try to couple our insight from the education discourse with which we engage with the insights we have gained, and continue to gain, from our constant involvement with schools, classrooms and teachers. In this book, we have referred to some sources of further reading that might be useful in explaining or delving deeper into our thinking; at times, we have expanded on the rationale or justification.10

From time to time in schooling, particular authors or voices urging change or specific approaches become prominent and are quoted constantly. Ten years ago, politicians leant on the work of E. D. Hirsch to validate their position and today many schools cite Mary Myatt or Barak Rosenshine as justification of their approach. Of course, most authors, particularly when writing about curriculum theory, refer to, add to and summarise the theories of others; so, someone like Myatt, rather than introducing new research, is trying to help readers to appreciate the implications for their practice.

Within curriculum and pedagogy, there is rarely any groundbreaking practice. For instance, the arrival of technology did not change pedagogy that much as it allowed itself to be modified to be accommodated in classrooms. The much-vaunted introduction of synthetic phonics (later known as applied phonics) was built on the reawakening of traditional practices. Rosenshine’s principles of instruction were first expounded in the 1980s but only took hold in England nearly forty years later.

Few classroom developments are researched in depth. Most good research on curriculum or pedagogy needs to be long term; one example of this would be the work of Robin Alexander on dialogic pedagogy.4 This is high-level classroom-based research which has developed enhanced classroom processes proven by rigorous evaluation and analysis. Our work on the Curious Curriculum is informed by dialogic pedagogy without being driven by it.

University research rarely gains prominence in schools, so in recent years the Education Endowment Foundation has become a reference point for the efficacy of practice. Similarly, the Chartered College of Teaching is encouraging action-centred research and disseminating the results. We encourage teachers to make 11discerning use of the findings promoted by these organisations, as well as considering the emerging practices in curriculum and pedagogy from other nations, regions and continents, such as Wales, Scandinavia and Asia.

What matters, particularly in a school community or group of schools in a trust, is a shared philosophy for education. Can we articulate our views on childhood and learning? Do we agree on how children should be treated and how they should encounter learning? Are we clear on the teacher’s role? Are we clear on what constitutes success in our schools? Can we use new thinking to inform and improve our practice?

A brief history of curriculum and pedagogy in primary schools in England

Before we begin our story, it might be helpful to sketch out the background to the way in which curriculum and pedagogy have evolved over time. Few things are new in education and many debates are very old. Whenever a school sets out to update, renew, change or develop its practice, it does so as another step on a long professional pathway. So it was with us as we sought to build a shared outlook with a group of people who had very different starting points and histories in the world of teaching.

It is hard to imagine that until relatively recently teachers could make their own decisions about what they taught and how they taught it. It was widely assumed that children’s ability was fixed, and the professional ability or contribution of teachers went largely unquestioned.

For a long while after the Second World War, most primary schools would follow a fairly common curriculum, mainly drawn from textbooks that children would work through with teacher guidance. The three Rs of reading, writing and arithmetic would fill most of 12the morning and afternoons would include geography, history and physical education. There was some science but it was generally undeveloped and often masqueraded as ‘nature study’ lessons. Most primary children experienced arts and crafts, including needlework, weaving, drawing, painting, pastels, clay and lino printing. Music was also present in the majority of schools with children singing and having an opportunity to play percussion instruments regularly.

Gradually, advocates of what came to be seen as progressive methodology began to question this tradition. Most of the change was in terms of pedagogy, with some teachers organising children into mixed-ability groups or allowing them to discover as opposed to being instructed. Such approaches were fuelled by the work of Jean Piaget, who described the stages of development through which children need to travel and questioned whether the school system enabled or constrained that development.5

Some teachers began to use their time more flexibly, shifting to an integrated day (or curriculum), and others began to work with colleagues on team teaching – sharing expertise and teaching loads. Publishers sensed a growing market and began to produce individualised programmes, usually focused on work cards that children could manage and progress through at their own rate. There was a heavy emphasis on the display of children’s work on classroom walls as the children stopped using exercise books for all their recording and teachers encouraged a range of responses to the stimulus of cross-curriculum themes and topics. Architects designing new schools also sensed the mood and designed modern buildings to enable these approaches, which were open plan to allow flexibility. Teachers who appeared forward-looking often secured promotion and, in turn, encouraged their staff to embrace the new order and 13practices. This shift of emphasis reached a crescendo in 1968 with the publication of the Plowden Report, which urged primary schools to adapt and see their role as guiding children through learning with a broad and practical curriculum experience.6

The problem was that the effectiveness of the new, more ‘progressive’ practices was variable, although probably no more variable than ‘traditional’ practices. The traditional practices were at least understood by most adults, since they had experienced them themselves as children. (Even if they had achieved poorly at school, they had learned that schools got it right and that underachievement was their own fault or destiny.) Many in the profession were reluctant to adopt the new approaches: in the new open-plan schools, some teachers created makeshift classrooms using furniture (and sometimes children’s bags!) to build ‘walls’, so they could continue with formal, didactic lessons.

In the early 1970s, the rearguard action against progressivism gained pace with the publication of what were called the Black Papers,7 which set out to cast doubt on the shift from traditional approaches. The tensions reached fever pitch in 1976 with the publication of the Auld Report on the failures at William Tyndale Primary School in London,8 which were portrayed by many as the natural outcome of the progressive approach. In the same year, Neville Bennett’s study of thirty-two primary schools in Lancashire appeared to indicate that traditional teaching styles led to greater pupil progress than 14progressive methods.9 While the findings were disputed, not least by Bennett himself who said that he had struggled to find a school not using traditional approaches, the book played into the hands of the sceptics. In October 1976, the then prime minister, Jim Callaghan, made a watershed speech at Ruskin College calling for a Great Education Debate to bring consensus.10

Callaghan’s speech brought to an end a period of optimism and trust in schools (and other public services) that had existed since the war and began an age of doubt and distrust during which the arguments continued. In 1978, a report produced by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate (HMI) urged a balanced approach using didactic alongside discovery approaches,11 and HMI began publishing regular discussion documents on aspects of the curriculum to encourage debate and careful development of improved pedagogy.12 However, as the economy changed and families moved to different parts of the country for work, the variability of schooling became increasingly apparent to parents. Different expectations on children were exposed and parents witnessed the diverse routines and practices in schools. Issues such as children studying the Romans, for example, more than once because of a move of school began to be seen evidence of a lack of coordination.

In 1988, the secretary of state, Kenneth Baker, brought in the Education Reform Act 1988 which began a process of centralising 15the school system.13 It included arrangements for a national curriculum, which came into force in 1990. The national curriculum organised the primary phase into Key Stages 1 and 2 and structured learning by subjects with attainment targets. The Act did not specify approaches to teaching but it did bring in Standardised Attainment Tasks (SATs), which would help teachers and parents to find out how well their children were performing compared with average expectations.

In 1992, the government established the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted). The first inspection framework had a significant focus on whether schools were ‘covering’ the national curriculum. The National Curriculum Council and Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, which was replaced by the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) and the Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency, produced guidance on how best to teach the new curriculum,14 and the official endorsement meant that many schools resorted to using this in the face of inspection.

A relatively uniform curriculum began to appear across the country, although teachers complained that there was too much content and the recently created Ofsted inspections made them feel vulnerable, so the government commissioned the Dearing Review in 1994 to slim down the content.15 At the same time, data from the early SATs suggested that schools’ performance in English, mathematics and science was variable. As computers began to make the management of data more adept, it became apparent that this variability was not predictable entirely by virtue of home background. This led Ofsted to conclude that teaching was a key variable, and therefore the 16inspection framework was changed to place less focus on curriculum and more on teaching quality.

In 1997, the Blair government swept to power with the promise of raising school standards; among their flagship programmes were the National Strategies for literacy and numeracy.16 For the first time, central government was recommending pedagogic approaches through the literacy and numeracy hours, which balanced teacher direction of learning with whole-class and group work as well as including some practical work in each one-hour lesson. The rise in standards was credited largely to improved teaching, but the high-stakes accountability of league tables and inspection led to widespread concerns that the curriculum was being narrowed. The government attempted to counter this with the publication in 2003 of Excellence and Enjoyment, which urged schools to spread excellent teaching across the range of children’s curriculum experiences.17

This was followed later the same year by the publication of a new strategy in response to the tragic death of a child and growing concerns about childhood: Every Child Matters.18 The initiative was generally embraced by schools. The five outcomes – being healthy, staying safe, enjoying and achieving, making a positive contribution and achieving economic well-being – appealed to teachers and answered many of the concerns about the narrowing down of the curriculum. 17

The Rose Review of the primary national curriculum began in 2008.19 It proposed a rounded school experience with six areas of learning (as opposed to subject divisions), which met the expectation of Every Child Matters within schooling. However, just before its approval in 2010, a general election was called and the draft bill was not supported by all parties and did not pass into legislation.