A Midlands Odyssey E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nine Arches Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

In A Midlands Odyssey ten writers take the stories of Homer's Odyssey and transplant them to the English Midlands. With a range of settings – from smart canal-side apartments to late-night launderettes – these stories are wonderfully inventive and offer a down-to-earth take on one of the world's greatest pieces of storytelling. 'The Odyssey theme, so rich with its tales of wandering Odysseus, the lure of the Sirens, the loss felt by Penelope and those gruesome reports across time from the underworld, energizes the ten writers here, providing a pretext for a fine array of inventive and imaginative stories, attuned to the legend, aslant to the Ancient World, adventurous in their address. If the topology is contemporary and centrally oriented, and the themes entertainingly current, this anthology is certainly not Midlands miscellaneous; it's the opposite of drab urban realism: a mere seagull's cry, only the odd whisper and rumour away from Ancient Greece itself.' Alan Mahar 'An inventive and intriguing project, distinguished not only by the power of its Homeric reimaginings but by the superb quality of the writing throughout.' Jo Balmer Stories edited by Polly Stoker, Elisabeth Charis and Jonathan Davidson. Includes stories by: Yasmin Ali, Lindsey Davis, Elisabeth Charis, Kit De Waal, Charlie Hill, Paul McDonald, Richard House, Dragan Todorovic, Natalie Haynes, David Calcutt. This book is also available as a eBook. Buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 163

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

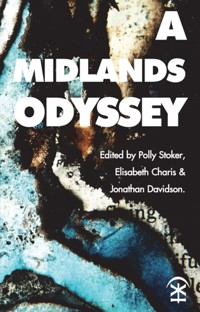

A Midlands Odyssey

A Midlands Odyssey

Edited by Polly Stoker, Elisabeth Charis and Jonathan Davidson

ISBN (ebook): 978-0-9927589-9-8

ISBN (print): 978-0-9927589-8-1

Copyright © remains with the individual authors, 2014

Cover photograph © Eleanor Bennett

www.eleanorleonnebennett.zenfolio.com

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, recorded or mechanical, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The individual authors have asserted their right under Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work.

First published October 2014 by:

Nine Arches Press

PO Box 6269

Rugby

CV21 9NL

www.ninearchespress.com

Printed in Britain by:

imprintdigital.net

Seychelles Farm,

Upton Pyne,

Exeter

EX5 5HY

www.imprintdigital.net

Ebook conversion by leeds-ebooks.co.uk

A Midlands Odyssey

Edited by Polly Stoker, Elisabeth Charis and Jonathan Davidson

A Midlands Odysseyis a Writing West Midlands / Birmingham Literature Festival project managed by Owl Productions.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama for this project.

CONTENTS

YASMIN ALI

In the Lap of the Gods

LINDSEY DAVIS

The Telemachus File

ELISABETH CHARIS

So Far from Home

KIT DE WAAL

Adrift at The Athena

CHARLIE HILL

Odysseus Weeps…

PAUL McDONALD

Who Are Ya?

RICHARD HOUSE

Underworld

DRAGAN TODOROVIC

Every Storm

NATALIE HAYNES

The Two Penelopes

DAVID CALCUTT

The Old Man in the Garden

Reflections

Biographies

INTRODUCTION

THIS COLLECTION of ten responses to the Odyssey, one of two ancient Greek epics attributed to Homer, emerges at a time of immense popular interest in the myth, literature and thought of the ancient world. With formal classical education harder to come by, the dissemination of the body of texts known as Classics increasingly falls to artists and sees the opening up of literary conversations as old as the works themselves to new and divergent voices. ‘Not knowing Greek’, a thorn in the side of Woolf and Keats, is no longer an obstacle to participation in the transmission of texts like the Odyssey, as this collection bears out. Those previously disenfranchised from classical learning on the basis of gender, class and ethnicity are now at the forefront of classical reception, endowing ancient literature with new life and challenging Classics’ traditional elitism. Of course, the practices of revision, appropriation and versioning are nothing new but the sheer volume and variety of contemporary engagements with the ancient world is remarkable, something that this collection is both a product and a new example of.

Precisely why artists return, time and again, to these ancient stories is a compelling question but one without a definitive answer. The idea that the longevity of these texts lies in their saying something universal about mankind is simply too easy an explanation, and often neglects the very specific and deliberate ways in which different times and places read and recreate these works anew. Explicitly ‘situated’ in the Midlands, for example, our collection forms part of a longstanding tradition of epic storytelling while simultaneously remaining local and of its time. It is perhaps more helpful to think about recurring themes and images that may characterise a ‘moment’ of reception. If we reflect on the mechanics of the writing process, drawing on the relationship between the old text and its reincarnations, important questions emerge that are key to thinking about the interplay between the ancient and the contemporary. Where does the Odyssey end and the new work begin? When we read a piece from the collection, whose voice are we hearing; that of Homer, the author or a melding of the two? What is Homeric about these retellings; is reception in a word or phrase, an image or theme?

Our anthology is certainly striking for its lack of violence, a noticeable contrast to the Odyssey; the suffering here tending to be internal and cerebral as opposed to bodily. With graphic images of atrocities channelled directly to us every day on our television screens and over the internet, is there a sense in which fantastical representations of suffering, such as we find in Homer, are in bad taste; at best, inadequate and at worst, offensive?

Moments of humour and lightness do feature throughout the collection but it is a recurrent sadness and pathos that emerges most profoundly and it is in this way that our contemporary receptions most clearly meet and build upon their ancient model. Whilst reminding us that the Odyssey is a story of loss and waste, there is a complementary thread of interpretation that sees this world-weariness as something equally appropriate to the here and now. It has been suggested, for example, that the sense of defeat emanating from some of our anthology’s characters may be redolent of a Midlands identity. What does this say about the place of the epic and its hero in the 21st century and would it even be possible to approach the Odyssey now without one’s reading being coloured by at least some cynicism and disillusionment?

The brief for the collection was simple: to write a short-story response to an element of Homer’s Odyssey in a contemporary Midlands setting. At first we envisaged allocating a different episode from the Odyssey to each writer but it became clear during the commissioning process that this overly ‘managed’ approach could not work, freeing up each writer to find their own way into the epic.

Although some retellings have a greater sense of closure and are more easily identifiable with their Homeric models than others, there is an overriding coherence to the pieces where, much like the ancient text itself, potentially separate stories come together to create a unified whole. Our anthology is in no way claiming to retell Homer’s Odyssey in its entirety nor to fully represent a region as complex and diverse as the Midlands. We hope instead that it is not too ambitious to anticipate that what we have produced here are ten episodes in the story that, over time, may be told as A Midlands Odyssey.

POLLY STOKERANDELISABETH CHARIS

YASMIN ALI

In the Lap of the Gods

Eddie walked through the car factory for the last time. His work here was nearly done.

‘You’ve seen my draft report to Frankfurt,’ said Eddie to the plant manager at his side. ‘We have two options. Both lead to productivity gains, one’s going to hurt more. What’s your take on this, Salim?’

‘Real technical innovation? That means job losses,’ said Salim. ‘But Turkey has enough history. We need to protect the future. We’re a young country.’

‘Good man,’ said Eddie, with a collusive nod. The phone pulsed in his pocket, but he chose to ignore it. In any case, he could guess who it was. Athene.

At the Athene offices Claire could scarcely contain her excitement. ‘I just know they’re going to love this,’ she said.

‘Maybe,’ said David, ‘but Poseidon’s after it, too. Don’t write them off. They sunk our last bid to Channel Four.’

‘But it’s not Channel Four, is it? This is Zeus,’ said Claire. ‘They want bold, edgy…’

‘They want ratings,’ said David. ‘Eyes on the prize, remember?’

So it was that Claire came to prepare for her meeting with the Commissioning Editor (Factual) at Zeus Television. The meeting took place at his club. The Olympus drew little attention to itself from the street; just a discreet doorway in Soho marked by a simple aluminium plate. Inside was a little different. A flunky dressed like a spangly Seventies game show host showed Claire up to the first floor library where Jolyon sat in a flamboyantly upholstered armchair reading on his tablet.

‘It’s a street in Birmingham,’ said Claire.

‘Benefits Street. It’s been done,’ said Jolyon. ‘Poverty porn, too depressing.’

‘This has got wealth and poverty, freaks and glamour,’ Claire began.

‘Heartbreak and humour?’ said Jolyon.

‘Check,’ said Claire. ‘Really. It has everything.’

‘Death?’ said Jolyon.

‘Absolutely,’ said Claire. ‘Athene are confident that this series reinvents reality television.’

‘So,’ said Jolyon, picking imaginary fluff from the knee of his burgundy trousers and dropping it to the floor. The gesture warned Claire that she was losing his attention. ‘Give me the pitch in one word.’

‘War,’ said Claire.

Jolyon looked up from contemplation of his finger nails. ‘OK. A sentence.’

‘Our cast have all been touched by war – profoundly,’ said Claire.

‘What war?’

‘War,’ said Claire. ‘Falklands, Balkans, Gulf, Libya. We’ve even got an old couple who fled Belfast in the 1970s and ended up losing their friends in the IRA pub bombing.’

‘I see the heartbreak,’ said Jolyon. ‘But where’s the humour? More to the point, where’s the glamour? And they’re all on one street?’

‘Around it. Bristol Road,’ said Claire. ‘It’s quite long.’

‘Let’s eat,’ said Jolyon. ‘I’m not sold on this, but I’m interested. I’ll hear you out.’

The walk to the dining room gave Claire the charge of energy she needed. Olympus members and their guests noted Jolyon. His aura was tangible. A red-top editor nodded, a fashionable writer stopped Jolyon for a quiet word, a BBC executive, no doubt looking for a route out of exile to Salford, air kissed the man. His power was a forcefield that took in his companion. The envious eyes of Claire’s peers and rivals took note. Athene Productions was one to watch.

At the table, the best table, supplicants approached to remind the man from Zeus of projects pending, and pitches proposed. An act from the theatre of power, this ended when Jolyon’s body language signalled that lunch had been ordered, and negotiations were about to begin.

‘The story?’ said Jolyon.

‘OK,’ said Claire. ‘We’ve people with PTSD, refugees, exiles, fighters, victims. But they’ve found a way through their experiences. They’re real characters.’

‘Characters, maybe, but where’s the story.’

‘The arc centres on one family,’ said Claire.

‘Are they British?’ said Jolyon. ‘Our audience need people they can identify with.’

‘Yes,’ said Claire. ‘From that longest of British wars, the class war.’

Jolyon spluttered, and reached for his glass. ‘Did you say “class war”?’

‘It’s the conflict at the heart of this series,’ said Claire. ‘It binds everything together. Birmingham used to be the centre of the motor industry. I’ve got a guy who worked at Longbridge all his life.’

‘Long bridge?’ said Jolyon.

‘Car factory at the end of our road,’ said Claire. ‘Or, at least it used to be. Synonymous with industrial militancy back in the day. Our old guy was a communist. Retired on a final salary pension and moved to a nice bungalow.’

‘Communist is exotic,’ said Jolyon, ‘but I’m hearing too much ‘old’. Not sure that works for our demographic.’

‘There’s a mid-century moderne angle,’ said Claire.’ The guy worked on the original Issigonis Mini.’

‘Niche,’ said Jolyon.

‘Just a detail,’ said Claire. ‘The old man’s son was apprenticed to British Leyland, too, as it was called by then. That’s Eddie. He fought the management, too. Lost his job, lost his pension…’

‘So?’ said Jolyon.

‘Lost his family,’ said Claire. ‘Had to move to find work. At first he commuted to Cowley. Then he worked at the Honda plant at Swindon. His marriage fell apart, leaving the wife behind with her baby son, Tel, but Eddie drifted on. Up to Nissan in Sunderland. On to the Czech Republic to help VW take over Skoda.’

‘I’m losing the plot,’ said Jolyon. ‘How does any of this make for reality television?’

‘It’s back-story, I know,’ said Claire. ‘But believe me, it works. Eddie’s ex-wife, Penny, still lives near Eddie’s dad. She’s done all right for herself. Took the license on a pub. Used to be a spit-’n-sawdust place for car workers. Now it’s a smart gastropub full of young professionals.’

‘This is beginning to sound like some kind of anthropological study,’ said Jolyon. ‘Benefits Street, I get. Made In Chelsea, TOWIE. But what is this?’

‘The back story’s important,’ said Claire. ‘What we want to do, across the arc of this series, is bring Eddie back. To reunite him with his dad, his son. Maybe even his wife. End the class war with a romantic meal in Penny’s bistro.’

‘Best laid plans. What if all hell breaks loose?’ said Jolyon.

‘We can handle that,’ said Claire.

It had taken some careful positioning to beat Poseidon to the Zeus commission, but Claire and her colleagues were determined to make this series Athene’s calling card in the business. Now all they had to do was make the programmes.

Izzy the intern rented flats for the crew in the Rotunda, a converted office building near the Bull Ring that was once the distinctive centre of the Birmingham skyline. Researchers armed with notes from Claire and David charmed the ‘cast’ and solicited the permissions. Claire herself worked on Eddie’s family. With their help, she felt, this project could be epic.

First, she visited Len, Eddie’s elderly father.

‘Come in, bab,’ said Len, answering the door of his neat bungalow. ‘Nice to see a pretty face.’

Len basked in Claire’s attention. She listened intently to his tales of working with Red Robbo, and made a show of taking copious notes.

‘You’ve got great tales to tell, Len,’ said Claire. ‘The stuff about your days as a shop steward is brilliant, but you must have some personal stories, too.’

‘I thought this was about class war?’ said Len. ‘We never called it that, mind.’

‘The human touch, Len,’ said Claire. ‘That’s what helps people to engage. Like when your son joined the firm as an apprentice. You must have been proud that day, walking in to work with him.’

‘I was on nights that week, bab,’ said Len. ‘Anyway, we took it for granted that if we had a lad he’d join us on the shop floor. ETU rules. Well, it was probably EETPU by then.’

‘What was that?’ said Claire. ‘EPU, or something?’

‘Frank Chappell’s lot,’ said Len. When Claire shook her head slowly, he added, ‘The electricians’ union.’

‘But you must have been pleased Eddie wanted to work with you, family pride?,’ said Claire.

‘Oh, ar,’ said Len. ‘I’ve always been proud of Eddie. Did well at Shenley Court, bab. And he didn’t let the battle for Longbridge defeat him. Works all over the world now. The stories he could tell you.’

‘But you miss him?’ said Claire.

‘Can’t say I don’t,’ said Len, ‘but the lad’s got his own life to lead.’

Getting Len to sign the consent forms had been easy enough. Getting him to stick to the script once they started filming was likely to be more difficult. They had cast him as a lonely old man who wants to see his son again before he dies. Still, it was all in the edit.

Penny was harder work. Claire couldn’t ingratiate herself with the woman, so David tried an approach. In the flat over the pub he picked up a photograph of Penny’s son.

‘Is this your boy?’ said David, although he knew the answer.

‘Yes,’ said Penny. ‘Spitting image of his dad.’

‘Do you find that difficult?’ said David. ‘The resemblance?’

‘No,’ said Penny. ‘When Eddie went, that was difficult. They were difficult times for all of us, for the whole city.’

‘What happened?’ said David.

‘We hadn’t been married long,’ said Penny. ‘I mean, we’d known each other since we were kids, but after Tel was born we bought a house, mortgage, all that.’

‘Then the factory closed down,’ said David.

‘Longbridge wasn’t just a factory,’ said Penny. ‘Look, old people today, they still talk about the Austin. MG Rover by the time it closed, a shadow of what it had been, but to us it represented what we expected from life.’

‘A job for life?’ said David.

‘Look at Len,’ said Penny, ‘from apprentice to gold watch. Birmingham people used to think that was their birthright.’

‘Who do you blame for the collapse of your marriage?’ said David.

‘Our marriage didn’t collapse,’ said Penny. ‘It never stood a chance. Men like Eddie. Well, he’s like his dad.’

‘Meaning?’ said David.

‘He’d gone into British Leyland as an apprentice,’ said Penny. ‘He wasn’t a tankie like his dad, but he was Labour, a solid union man. It’s how he defined himself. He couldn’t have stayed with us and stacked shelves at Sainsbury’s. It would have humiliated him.’

‘But you were left alone with a child,’ said David.

‘That wasn’t easy. But Eddie always paid the bills,’ said Penny. ‘Generously. That’s how I was able to get this place. I was always financially secure.’

‘And Tel,’ said David. ‘How’s he doing now?’

‘That’s the irony,’ said Penny. ‘He’s doing engineering at Bournville College. On the site of the old Longbridge plant. Like father, like son.’

‘You know it’s a great story,’ said David. ‘A strong, attractive woman, left to bring up her son alone. She becomes a successful businesswoman, the boy maintains the family trade. And it would be terrific publicity for the business.’

‘That’s the only reason I’m even thinking of doing this,’ said Penny.

It was enough for Athene.

Eddie sat on the terrace of his Istanbul apartment with an early evening beer. He was doing a lot of thinking about the past, thanks to Athene. The television company had been astonishingly persistent. Emails, phone calls, promises of first-class travel, above all the attention of a charming young woman who had taken Skype flirting to a whole new level. Was it fate that he should return to Birmingham now? He’d been away so long. He was estranged from Penny, and scarcely knew his own son, except through the occasional photograph. A reunion would have been hard in the best of circumstances, but accompanied by a raucous television crew it might be hell.

For Athene, filming the minor stories for their series was easy. The American teenager who’d dodged the draft in the early 1970s, and now ran a chain of artisanal bakeries across the Midlands and the Cotswolds, just wanted to play the grey hipster and promote his sourdough. The Syrian student stranded far from home by war might have been too much reality for the reality genre, but with his boy-band looks and genial manner, Athene could cut him into the narrative without troubling the viewers unduly. The Somalis might have been a problem until they found an unusually tall, good looking family. The boy was already a promising basketball player, and Claire had managed to talk the daughter into going to a modelling audition where the agent had shrieked “the new Alek Wek!” Great telly.

But the multi-generational tale of Len, Eddie, Tel and the lovely Penny in her palace of a coaching inn was at the centre of the series. Len had proved to be more malleable than Claire had at first suspected. Nothing was too much trouble for the cameras.

‘Can we do that again, Len?’ said Claire. ‘From the bit about Eddie’s first day at Longbridge.’

‘Alright, bab,’ said Len. He coughed, raised his head confidently, and held out a photograph towards the camera. ‘This,’ he began, ‘is my lad Eddie when he was sixteen. I was that proud when he followed me into Longbridge. We walked in together that morning as Men of the Midlands.’

‘Fabulous, Len,’ said Claire. She now had something she could use with the archive footage of Mitchells and Butlers beer commercials for ATV.

‘Now just a few shots we can use when we cut it,’ said Claire.

‘In the garden again?’ said Len, fancying himself something of a pro now.

‘Kitchen, this time, I think,’ said Claire. ‘How about making a nice cup of tea?’

‘Two sugars for you, Rashid?’ said Len to the cameraman. To Claire he said, ‘You’re sweet enough, bab.’

‘Can you just make the one cup?’ said Claire. ‘Then take it and sit down in the armchair over there.’

‘Not my usual chair?’ said Len.