Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

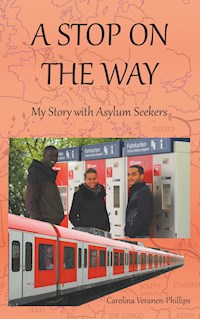

Carolina, a French woman living near Munich, embarks on a social journey with the asylum seekers in her town. She wants to welcome, share and integrate. She quickly finds herself on an emotional roller coaster, mixed with joy and hope, as well as sadness and deception. Where does this adventure take her? ------------------- July 2013. Germany is expecting the arrival of a large number of refugees soon. The refugees are to be dispatched homogeneously around the country. This causes concern and calls into question. Carolina, married, mother of two and new in her community, wants to get involved, she wants to help. Her social network is not very wide yet and she doesn't know how the administrative system really works but she is motivated and determined. How will she commit? What are her plans? This autobiography, aiming at showing various aspects of immigration in Europe, recounts the social journey of a woman amongst the refugees in her town. In this astonishing adventure, her path will cross the path of a great number of travellers seeking for help, including Mariam, an Eritrean injured woman soldier, who has regular epileptic fits, Amadou Sane, a young Senegalese who left his motherland full of hopes and dreams and Bahoz, a young and depressed Iraqi journalist, prosecuted by ISIS. This work describes the determination of a young woman in her quest to facilitate the integration of refugees in her town, intertwined with their sad and often tragic stories. Do they really have a chance to stay and be accepted? What is the reality?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the author:

Carolina Phillips, biologist, wife, and mother of two, is a very active volunteer in her community of Poing, near Munich, in Bavaria.

At the end of 2013, she started, developed and managed a project with the objective of helping to simplify the lives of asylum seekers and their integration into the local community.

Thanks to her multi-cultural origins and many trips overseas, Carolina loves welcoming new people, embracing new cultures and languages in her life. She is driven in her work by her passion and the pleasure of bringing people together.

She is convinced that an open mind and tolerance help to make our world a better place.

Other publications by Carolina Veranen-Phillips:

Mint Tea to Maori Tattoo! ISBN 9780755214730 (in English)

Haltestelle Poing ISBN 9783741210341 (in German)

Leur Périple ISBN 9782322084081 (in French)

To all the people who sought refuge in Poing

A big thank you to all those who helped me, believed in me and encouraged me. Without you I would not have accomplished as many things as I did.

I would specifically like to thank my family for their patience and Julie Phillips and David Schofield for helping with the proof reading.

The names of people presented in the book, other than those of the author Carolina Phillips and Mrs Ismair, who gave her permission, have been changed for reasons of security and the protection of identity.

Contents

P

REFACE

I H

OW

I

T

A

LL

S

TARTED

They’ve Arrived!

At the Restaurant

Preparations

Pakistan

The First German Lesson

Let’s eat!

II F

ATIMA AND

A

ZIZ

At Fatima’s Place

Fatima and the German Class

Yarmouk

The Boat Journey from Egypt

The People Smugglers

Catania - Munich

The Quarrel

Asylum Granted

Aziz

III C

HANGES IN

P

OING

New Families on Passauer Straße

Escape from Eritrea

Some Work for our Pakistanis

Events

The Sports Centre Camp

The People of Poing Open Up

IV E

PISODES FROM ANOTHER

R

EALITY

Kamel

Amadou

Ibrahima

Bhata

Kamara

Khalid

V D

ISAPPOINTMENTS AND

H

OPES

The Long Wait

Impact Day

Some News about Aliou

VI A N

EW

W

IND

New Strategies to Find Work

Successful Asylum Seeker-Mentor Relationships

The Thank You Party

The Finishing Line

E

PILOGUE

M

APS

T

HE

A

SYLUM

A

PPLICATION

P

ROCEDURE IN

G

ERMANY

F

ACTS ABOUT

C

OUNTRIES

Preface

The first thing I asked myself on reading the original title of the book “Haltestelle Poing” (literally “Poing Station”), is what does it really mean.

To my way of thinking, in this context “station” could be considered like a milestone, or an event that defines our lives. Without them, we wouldn’t have any points of reference and would go through life with less assurance. We all need our milestones in order to go forward.

Many asylum seekers have left their country in quest to find a safer place to live. Hundreds of them arrived in Poing, where for the first time they found a safe home, a refuge.

These asylum seekers have been welcomed in Poing by Carolina Phillips, a volunteer at the Family Centre, who, with her group of volunteers, have prepared for their arrival.

Thanks to her dedication, unlimited empathy and overflowing creativity, and to the many projects undertaken by the Family Centre, our community has become a break from danger for the asylum seekers on their way to a new life. What drove her to helping the new comers are her interest in other cultures and her curiosity. A great opportunity for our community.

On behalf of all our volunteers, I thank Carolina Phillips for her engagement in the face of such a social challenge.

As for you, dear readers, I leave you to discover the beautiful and the sad moments in this book. I hope that it will arouse your curiosity and you will feel inspired by these projects of support and integration for asylum seekers, whoever they are.

Albert Hingerl

Mayor of Poing

I How It All Started

They’ve Arrived!

February 2014. I received a telephone call that was unexpected. But the information that Thomas Gerck shared with me was not. The journalist from the Munich Merkur gave me the news that I was waiting for.

“Hello Mrs Phillips, perhaps you are already up to date, but I wanted to inform you that the first asylum seekers are here. They arrived in Poing yesterday.”

As soon as I hung up, I sensed my heart beating to the rhythm of my thoughts: How many are there? Where have they come from? What ordeals have they experienced? Innumerable questions surged in my mind, for which, as yet, I did not have answers.

I armed myself with patience. I had been waiting a long time for them to arrive and had prepared myself to be there for them, to help them.

They had arrived at last: four men from Pakistan, the first asylum seekers in Poing. The time had now come to go and meet them. But how best to begin? Should I simply go and visit them? Or should I first obtain approval from the Local Council (Landratsamt, or LRA). Where were they living exactly? I needed information and contacts, but I had neither. Everything had started in the month of August 2013. The mayor of Poing, a small town near Munich, had invited the members of the local community to an evening meeting in order to demystify the question of asylum. It would be the opportunity to explain the situation of asylum seekers in Germany and to explain the repercussions on the town of Poing. Because of the growing number of migrants in Europe, it was expected that Germany would equally be confronted with this reality. In fact, since 2011, the number of asylum seekers in Germany had grown by about 50% each year. In 2013, there were 127,000 and in 2014, 202,834. In 2015, the Federal Office for Immigration and Refugees (BAMF) had received 425,035 requests.

It wasn’t only large cities like Berlin, Frankfurt and Munich which had been called upon; the towns and villages around these urban centres where equally expected to take support asylum seekers.

Poing is a town both small and young. It has a population of 15,000 and is located east of Munich, in the region of Ebersberg. Around twenty of the community members took part in this meeting about the asylum seekers. The mayor and representatives of the LRA of Ebersberg were trying, based on facts and figures, to examine the possibility of welcoming the asylum seekers into our community and making provisions to that effect. However, the real objective of the meeting was to find accommodation for the asylum seekers.

It was during the course of the evening that I met Bettina Ismair. It was a rewarding meeting, decisive and inspiring for the events to come. Years before, Bettina had developed a program for the children of asylum seekers called “Open Door – Open Heart”. Once a week, the volunteer families opened the doors of their homes to the children and in this way permitted them to be part of their family for an afternoon. The observations and interventions of Bettina Ismair during the course of the evening revealed her broad experience in topics relating to asylum. It fascinated me. Wanting to know more about her work, I approached her after the meeting. She had managed to launch a great project all by herself and to change the lives of many children, and in doing so, that of their families. Her experience inspired me to set up a similar project in Poing. Even though at this point I didn’t know how much I wanted to involve myself in the project, I was determined to take action. To achieve this, I had only my own determination and a few contacts at the Family Centre. I did not know how the representatives of the LRA, and especially the mayor, felt at the end of the meeting. I did not know if they were satisfied with the reactions of the citizens.

However, I knew that this evening had set off something inside of me: I felt inspired. A sort of awakening. The theme had touched me. On my way back home I felt that everything had become clear: I wanted to help. It felt good. At that moment, I knew that I had made the right choice. I just didn’t know how much this decision would change my life.

We were now in the month of February 2014, and our first four asylum seekers had arrived in Poing. Close to six months had rolled by since our meeting with the mayor. I took the opportunity to adapt myself to the situation and to complete the preparations. I was very happy that Thomas Gerck had informed me of the arrival of the asylum seekers. It isn’t easy for new arrivals to fend for themselves in the community.

The first time that I had met Thomas Gerck was at the Family Centre, some time ago. He was writing an article about the welcoming role of the Family Centre on the new citizens setting foot in Poing and interviewed me because I was one of them: I had just arrived three weeks beforehand. For the new people in the town, like me, the Family Centre constituted an ideal springboard to forge links with members of the community. Several times a week, a coffee meeting was held there. It was a good opportunity to meet new people and to make friends. From the start, I felt welcome. I was able to talk and exchange advice with other mothers who had similar problems and concerns as I did. If I hadn’t discovered these coffee meetings, I would never have been able to volunteer for the cause of asylum seekers.

Later, I contacted Thomas again to talk to him about the charity event that I had organised on behalf of the Family Centre, in February 2014. The goal was to raise funds for future asylum seekers. As it happened, the event was held a week before the arrival of the asylum seekers, something we were unaware of at the time. Gerck had sent a photographer to document the occasion. This was one of the reasons why he called me the day after the arrival of the asylum seekers. He wanted to speak to me about his article on the charity event. Without his call, I would not have been informed so promptly of their arrival. Now I only wanted to meet the four new comers. Meet them in order to start the help process. Thomas Gerck had told me that Marie Berg from “Poinger Tafel” (the food bank of Poing) had registered them at the town hall. I didn’t know Marie Berg and certainly didn’t know about the food bank. However, I didn’t have much trouble finding her contact details. I rushed to call her and was disappointed to get her voice mail. I left a message and only thirty minutes later my mobile phone rang. It was Marie, “Hello, Mrs Phillips. You called me?” I was pleasantly surprised to hear her voice. I quickly explained the situation. I told her that I was on the board of the Family Centre and was about to set up a project to help the asylum seekers. To do this I had to meet them first. Was she able to help me?

There was a brief moment’s silence at the other end of the phone. Then came the long-awaited answer, “Tomorrow, I am organising a lunch for the people who attend the food bank. I have also invited our four asylum seekers. Would you like to join us? Do you speak English?”

After hanging up I jumped in the air and let out a “yes!” while making a victory gesture with my hands, as if I had won a set at tennis. It was all happening finally. That night I went to bed happy and serene.

At the Restaurant

When things are meant to happen, they feel right. No wonder I felt full of energy and on top of the world the next day. I couldn't wait to meet our first asylum seekers. I had been waiting since August the year before. Now I was ready to act and it felt good. Meeting the new comers didn’t seem that exotic or amazing to the eye of the observer but for me it was. In fact for me, it was going to be something symbolic: the beginning of something new, a new chapter in my life, not only theirs. The start of a project... That day I was committing myself to a cause and that meeting was the key to opening the door to that engagement, something I had never really done before. I had never really been involved in the community or with a cause that matters. In fact I had never been involved in anything at all. I had played sports but always stayed out of the sports club's life, just being an observer, never committing myself. I have always been busier with all my little personal projects and dreams that I had never found the time to actively commit myself to a cause, a club or something of that sort.

When I arrived at the restaurant, I saw a large table full of people. There must have been about thirty men and women. As I pushed the door, all eyes turned to me. I looked around and noticed Marie Berg. When she saw me, she introduced me to the group. I sat on the side of the table where the asylum seekers were sitting. At first, I was surprised to see only three men. I was expecting to meet four Pakistanis. I was told that the fourth man, Nuwair, hadn’t wanted to come, as his situation was different from that of the others. In fact, he had already spent several years in Austria, before coming to Germany. He had already learnt German. Perhaps he had also already taken part in a welcome ceremony, and therefore didn’t feel the necessity to repeat the experience. Maybe he simply didn’t want, or need, our aid. And perhaps he already knew that his integration into a new community would not accelerate his request for asylum. Such requests go through the Federal Office for Immigration and Refugees or BAMF (see “The Asylum Application Procedure in Germany” pp 176-177): they are not processed and examined on the spot in the community1. Being integrated or not in a German municipality or speaking German has no bearing on the outcome of the asylum procedure. The only thing which counts is what happened beforehand in the country of origin.

Then I introduced myself. In fact, I had no idea how to best go about it. Who was I? Who was I representing? What could I say, what could I offer? My project was only in its infancy. I still had no specific plan. I wanted first to observe and get a better idea of the situation. I also did not know what the expectations of the asylum seekers were. Maybe they did not even want our help. Who knows? First, I wanted to understand the situation of the asylum seekers and simply welcome the newcomers. The situation in which I found myself was totally new, not only for me but also for the whole community of Poing2.

In English, I started to explain that I was part of a group of volunteers who wanted to help the asylum seekers in the community. I added that our group could familiarise them with the German language and culture and, most importantly, make sure that they felt welcome in the community. Azfar was the only one who could speak English. Arfeen and Hosni, despite their efforts, could only say a few words. As Azfar had arrived in Europe by plane, he must have had a tourist visa. Arfeen and Hosni had taken the long and painful route passing through Greece (Map 1, page →).They had some knowledge of Greek but practically no English. As my Greek is almost non-existent and my Urdu3non-existent, I could only talk to Azfar.

Speaking with him brought back memories. It reminded me of my time in England, where many Indians and Pakistanis lived. One can often confuse the two, although they come from two totally different cultures with distinct political and religious contexts. During the second half of the 20th century, many Indians and Pakistanis immigrated to Britain. In Germany, on the other hand, we rarely meet them. That’s why my first question to Azfar was to ask why he wasn’t seeking asylum in England. After all, his English was good. By comparison, German is not an easy language to learn, and someone who does not speak the language of the country does not usually have good employment prospects, nor the opportunity to start a new life. Azfar had found out while he was in Pakistan, that England was already overloaded with Pakistani asylum applications and that the chances of obtaining asylum were clearly higher in Germany.

How could I be useful? What are your needs? It is through these two questions that my humanitarian work began. Azfar translated the questions into Urdu for Arfeen and Hosni, who smiled at me politely. I am sure they were wondering who this woman was, full of energy, and asking them what they needed. Azfar took several minutes to think about it. They probably needed so many things that they didn’t know where to begin. Obviously, I was not able to fulfil all their wishes or grant all their needs. The message that I wanted to convey, was that I wanted them to feel at home here. I wanted to help them to integrate into society and to show them they were welcome in Poing. After a moment, Azfar replied, “Maybe German courses? We want to learn German.” Of course... German courses!

I looked at them and smiled back. Many smiles were exchanged that day. Meanwhile, my brain was processing the new information. Now I had to act. What could I offer? I had at my disposal a group of volunteers who were just waiting to get their hands dirty. I had three Pakistanis who wished to learn German. I even had a place where we could meet: the Family Centre. There was a coffee corner with round tables where the atmosphere was reminiscent of a real Café. They were also open Tuesday and Thursday mornings. I spontaneously invited the Pakistanis to come there next Thursday at 9:30. The news seemed to cheer them up. For my part, I only had two days to get organised and to set up German courses. There we go! The project was starting. Thursday would be our first German lesson.

The food arrived. The three men and I ordered vegetable pasta. In Pakistan, the majority of the population are Muslims and therefore do not eat pork, a meat that is practically part of every meal in Germany. And we were in a German restaurant. By opting for a vegetarian meal, the Pakistanis were avoiding any unwelcome surprise.

We started to eat. My plate was brimming with steaming pasta, a huge portion, sufficient for three people. Soon, I realised I would not be able to finish it all. I felt bad. I still had so much pasta on my plate and I knew I could not eat everything. That would make a bad impression. The food bank offered free lunch to people in need. I did not want to leave food. It would be a disaster. I focused all my concentration on my plate and its contents. It was almost painful. I gathered my courage and almost got to the end.

Azfar and Hosni had no problem finishing their plates, whilst Arfeen only managed a third of his. For him too, the portion was too big. He was small and thin, and it was obvious that he could not eat such a great quantity. He ended up telling me that he couldn’t do it. I had no trouble believing it, since I was in the same situation. All the others had finished their plates and were waiting for us to do the same. When we explained that we were finished, Marie Berg looked surprised to see that Arfeen’s plate was still full. “Don't you want to finish it?” she asked him. I replied for him, saying that he had eaten his fill and that he couldn’t eat anything more. It was on this surreal note that my first meeting with the asylum seekers ended.

Preparations

Even before the arrival of the newcomers, I knew that German lessons would be one of the most important activities to organise for the asylum seekers. The volunteers were ready to fulfil this function but had no training as German teachers. However, their natural knowledge of the German language would be sufficient to teach the basics. What we needed most, in my opinion, were friendly and open people, who had time to meet regularly with the asylum seekers. It was important for the young men to know the people of Poing who could support and advise them. Individuals who could answer their questions of an administrative nature, or who could accompany them to the doctor. What I wanted first and foremost, was to offer the asylum seekers a presence. Someone who would be there for them.

The meal at the restaurant with Marie Berg, Arfeen, Azfar, Hosni and all the other guests from the food bank represented the situation for asylum seekers in Poing and throughout Germany: a few people trying to help newcomers and, as best they can, communicate with them, while most of the population watched from afar and wondered what drove these men and women, who look so different from them, to come here. The media was full of reports on asylum seekers and, despite everything, the population did not really know what to think of this new situation.

One of my goals was to create a win-win situation for everyone in the community. On the one hand, I wanted to facilitate the integration of asylum seekers in our town, and on the other, I wanted to give the community the opportunity to discover new cultures, those that the migrants had brought from their countries. That mutual exchange was for me, and still is, incredibly rewarding for both sides. We offer our protection to the newcomers from diverse backgrounds and, in exchange, they enrich our culture with their way of life. For me, it is a step forward towards a world governed by peace and mutual understanding. And every step counts, as small as it is.

If only there was no fear. Fear of the unknown. It is clear that people are afraid of what they don’t know. Not only in Germany. It’s a universal law. The unknown is always something mysterious, uncontrollable and inconceivable. Often, we remove this uncertainty from our visual field and our life. Without necessarily discriminating, we close ourselves to what is new. To me, this lack of openness is nothing more than a passive form of discrimination.

In this case, the unknown takes the form of another culture, that of the immigrants. By choosing understanding and acceptance instead of exclusion, we can help build a more open society.

Moreover, we must be aware that it is not just our culture that is good and important. Any other culture is as important and enriching as ours. Any other way of life has the right to exist. Unfortunately, we often struggle to see how other cultures can enrich and strengthen our society.

Our lifestyle is marked by haste and duty, but this stress is not found in all cultures. For many of the asylum seekers, it’s more important to spend time with family and friends. Seniors still play an important role in society, while our seniors are often placed in retirement homes and neglected. Children listen to their parents and respect them. Some societies have a good relationship with death. It is not taboo, but rather a reality, and when the time comes, the family is already prepared and has no problem talking about it. In our society, we don’t talk about death, and many people find themselves alone to face this tough stage. It is precisely these strengths of different immigrant cultures which can bring a considerable enrichment to Europe.

It can be very rewarding to step out of our comfort zone sometimes, to take some risks, in order to try to understand what is new to us, what we don't know. Some people take more risks than others. The more adventurous will show courage and will meet other cultures. I consider that I belong to this group of the adventurers. I love being part of a heterogeneous group of cultures. I feel incredibly at home in a multicultural environment. It’s like I have a piece of the world in me.

And this feeling has been reinforced by my life experiences. During my trip to Cairo in 2003, I remember walking along a maze of narrow streets towards the Citadel in the Muslim quarter of Cairo when I met Mr Fouad. Mr Fouad, who was sitting in a Café, called out to me. He was an elderly Arab dressed in a long white robe and a white hat, smoking a cigarette. I don't know if it was the white robe or the hat but he seemed like a wise person. In my mind he resembled the Arab poet Khalil Gibran, even though I don't know what Khalil Gibran looked like. He asked me where I was going. “To the Citadel”, I replied. “Ah! Come and sit with me instead, the Citadel is closed today!” In rough English, he invited me to have a coffee with him. I accepted his invitation. The Citadel could wait. Then he called the waiter, Mr Said, and asked him to bring something to drink. I can’t remember what I drunk first, but I had the opportunity to taste a variety of drinks, from coffee to mint tea to sugarcane-based drinks. I must have spent an hour drinking and smoking cigarettes with him. Probably Mr Fouad spends his time sitting in this Café, waiting for the day to end. It’s just what I imagine, I do not know if it’s really the case. During the time that I spent with him at the Café table, he showed me people and children and explained to me, “That’s my nephew. That’s my son.” As I was about to leave, he invited me to come and have dinner at his home with his family in the evening. I declined the invitation. I will never know what I missed. But in any case, the invitation made me very happy. In Europe it’s not common for a stranger like Mr Fouad to invite you to dine with his family. On the other hand, in the Middle East and in parts of Africa, I have often experienced it.

At that time, I did not expect and could only have doubted that I would be given the same hospitality soon in my own town every time I visited Fatima and Aziz, a Palestinian family from Syria.

After the first meeting with the Mayor, in August 2013, I started thinking seriously about how I could help. All alone, I would not be able to manage a large project. So, I had to get more people interested. At that time, I had just been elected to the board or directors of the Family Centre. I therefore had some influence within the organisation and the decisions that were made. The administration and its contacts with the municipality were of great help for the next steps.

I asked them to start a project inside our walls for asylum seekers and I obtained their blessing on the spot. My idea was materialising. I found out that I could advertise in the local press on behalf of the Family Centre. Which I did. I put an ad in the local Poing newspaper to find volunteers who would like to lend a helping hand for the arrival of the asylum seekers. I received the first calls a few hours after publication. Every day people called, every day my list of volunteers grew.

I did not expect to receive so many phone calls and emails! This showed that our fellow citizens were happy about helping the newcomers. I was really stimulated. That was the impetus that I needed for my next challenge: the ability to respond to phone calls and emails. I prepared myself as best I could, but Germany was a new country for me too, and I had not yet mastered the language. This did not seem to matter much, because when people show kindness and want to help, the language barrier disappears.

I answered the emails as best I could. Then I replied to the phone calls, trying to explain the situation and the plans that I had in mind, as simply as possible. I was not able to give details, the situation was not yet clear, even for me. Gradually a group of volunteers came together. We had virtually no information about the asylum seekers, nor on the next wave of newcomers. We did not know how many there would be, where they would come from and what they would need. Even less if they would accept our help!

My goal was to form a group of volunteers so that we would be ready when the asylum seekers arrived. For the rest, we would see. I would take care of that when the time came. I decided to stick to this idea. I was extremely motivated. After only a few weeks, the list of volunteers was complete. Between fifteen and twenty people had confirmed their support. I had never thought of receiving such feedback as a result of my ad. It gave me wings… and the courage to continue with my project.

I suddenly discovered another face of Germany, a face I had not seen before: people who were sincerely interested in offering their help. Those who called me had the same motivation as me. They wanted to lend a hand and offer their time to these people who had taken refuge with us after having travelled so many kilometres. This was how our group was formed, which from the start gave me the feeling that we could achieve great things. Over time, I would realise that the group was much more than a handful of volunteers. Month after month, links would be forged, and we would get to know one another. We would share unique moments and experiences, fight for the same cause, and in short, grow together. We would become an extremely well-connected community of friends. There would always be an attentive ear when we had worries or fears. We would be there for each other. We had set up this group to help the asylum seekers, but it would prove to be much more than that. We were also going to help each other.

For now, we were a group of volunteers, without asylum seekers to help. I felt however, that we were prepared for their arrival, whatever the date. We wanted to teach the newcomers some German and to explain to them the way of life in Germany in order to facilitate their integration into our society. I had never had any contact with asylum seekers, so, I had no idea of the German refugee procedure and system. I often felt terribly alone, because I did not know who could answer my many questions.

One morning, an idea came to me. Although the asylum seekers had not yet arrived, the volunteers were ready and wanted to take action. Why not organise a charity event to raise funds for the asylum seekers? The idea was immediately adopted, and we made the decision to simply combine our charity event with the Family Centre children’s theatre, which took place each year. The plan was to cook and sell cakes, then invest the proceeds into our project. Moreover, the sale of coffee and cake was a great opportunity to get to know the other volunteers in our group. The press was also invited: the Munich Merkur and the Southern German Zeitung. It was a way for the Family Centre to declare loudly and clearly to the people of Poing that it was encouraging this project and saying YES to the asylum seekers. I was very excited about finally learning about my ambitious colleagues!

1 February 2014. When I arrived at the Family Centre a small crowd was already waiting for me.

“Hello, I am Carolina!”

“Hello, I’m Astrid!”

“... and me, Hilda.”

No more complicated than that. I thought we would have a little time to chat, but our audience was already demanding coffee and cakes! In a short time, we were already overwhelmed! Nevertheless, I had my first glimpse of the people who had offered their help. I was able to see their motivation and kindness, even though I didn’t really know them yet! In addition, I had the opportunity to talk to the press. The organisation of such an event was something quite new to me. I learnt a lot. The day went by without a hitch. The press was very kind to us and wrote a lovely article about us. But what gave me the most pleasure, was that our group of volunteers got on well!

Pakistan

As I mentioned before, our first asylum seekers came from Pakistan. In Germany, we don’t know a lot about this country. In Great Britain the situation is quite different since they share historical ties. They also play cricket. After all, sport brings people together. Germany and Pakistan don’t have a common past, and they have very few links even today. Pakistan has more than 191 million inhabitants and the majority of them are Muslims. Pakistan ranks sixth amongst the most populous countries in the world. It borders the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman, right next to India. It shares other borders with Afghanistan in the west, Iran in the southwest, and China in the far northeast.

To better understand what drove Pakistanis to seek asylum in Germany, we need to look at the history of the country. In the nineteenth century, what is now called Pakistan was part of India, an English colony then. It was not