89,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Thieme

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Getting to the Point—Acupuncture for Small Animals

Where is the gallbladder channel and what happens when GB-6 is needled? Which point helps with food refusal? How should I needle, and does the point really fit my intended therapy concept?

This unique acupuncture atlas for small animals makes long searches superfluous!

Special Features:

- An introduction to the basics of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and a comprehensive discussion of the channel system and acupuncture point categories.

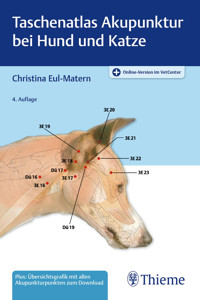

- Quick orientation thanks to the easy-to-use double-page spread layout: Indication, localization, technique, and depth of insertion are listed for each point on the left-hand page. On the right-hand page, a photo illustrates the position of the point on the dog's body in relation to muscles and bones.

New to the Second Edition:

- A chapter on the psycho-emotional basics of small animal acupuncture

- For important acupuncture points, the psychogenic effects are now described

This handy pocket-sized atlas is unique in the field and an ideal companion for veterinarians, animal acupuncturists, students, and trainees whose goal is to provide the highest level of treatment to the animals in their care.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 305

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Acupuncture for Dogs and Cats

A Pocket Atlas

Second Edition

Christina Eul-Matern, DVM IVAS Certified Veterinary Acupuncturist (CVA) VetSensus Mastertherapist (VSCETAO) ICREO Authorization for Further Training in Acupuncture from the Veterinary Chamber of Hessen, Germany; Head of VetSensus Institute for Sensological Diagnostics and Therapy and Tiergesundheitszentrum Idstein (TGZ) Idstein, Germany

207 illustrations

ThiemeStuttgart • New York • Delhi • Rio de Janeiro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available with the publisher.

This book is an authorized translation of the 3rd German edition published and copyrighted 2018 by Sonntag Verlag in Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart. Title of the German edition: Taschenatlas Akupunktur bei Hund und Katze

Translator: Sabine Wilms, PhD, Langley/WA, USA

Drawings: Templates: Martina Steinmetz, Dielkirchen, Germany; Dana Müller, Maintal, Germany Executed by: Malgorzata and Piotr Gusta, Paris, France; Angelika Brauner, Hohengeißenberg, Germany

© 2022 Thieme. All rights reserved.

Georg Thieme Verlag KG Rüdigerstrasse 14, 70469 Stuttgart, Germany +49 [0]711 8931 421, [email protected]

Cover design: © Thieme. Cover illustration: Template: Martina Steinmetz, Dielkirchen, Germany Executed by:Malgorzata and Piotr Gusta, Paris, France

Typesetting by DiTech Process Solutions, India

Printed in Germany by Beltz Grafische Betriebe 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-3-13-243454-7

Also available as an e-book: eISBN (PDF): 978-3-13-243455-4 eISBN (epub): 978-3-13-257915-6

Important note: Medicine is an ever-changing science undergoing continual development. Research and clinical experience are continually expanding our knowledge, in particular our knowledge of proper treatment and drug therapy. Insofar as this book mentions any dosage or application, readers may rest assured that the authors, editors, and publishers have made every effort to ensure that such references are in accordance with the state of knowledge at the time of production of the book.

Nevertheless, this does not involve, imply, or express any guarantee or responsibility on the part of the publishers in respect toanydosage instructions and forms of applications stated in the book. Every Every user is requested to examine carefully the manufacturers’ leaflets accompanying each drug and to check, if necessary in consultation with a physician or specialist, whether the dosage schedules mentioned therein or the contraindications stated by the manufacturers differ from the statements made in the present book. Such examination is particularly important with drugs that are either rarely used or have been newly released on the market. Every dosage schedule or every form of application used is entirely at the user’s own risk and responsibility. The authors and publishers request every user to report to the publishers any discrepancies or inaccuracies noticed. If errors in this work are found after publication, errata will be posted at www.thieme.com on the product description page.

Some of the product names, patents, and registered designs referred to in this book are in fact registered trademarks or proprietary names even though specific reference to this fact is not always made in the text. Therefore, the appearance of a name without designation as proprietary is not to be construed as a representation by the publisher that it is in the public domain.

Thieme addresses people of all gender identities equally. We encourage our authors to use genderneutral or gender-equal expressions wherever the context allows.

This book, including all parts thereof, is legally protected by copyright. Any use, exploitation, or commercialization outside the narrow limits set by copyright legislation without the publisher’s consent is illegal and liable to prosecution. This applies in particular to photostat reproduction, copying, mimeographing or duplication of any kind, translating, preparation of microfilms, and electronic data processing and storage.

Contents

Foreword

Preface to the Second English Edition

Preface to the First English Edition

Acknowledgments

Note from the Translator

I Basic Concepts of Acupuncture

1.What Does Acupuncture Have to Offer?

2.History of Acupuncture

3.The Principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine

3.1.Difference betweenWestern Medicine and TCM

3.2.Important Terms in TCM

4.The Channels

4.1.Function of the Channels

4.2.Main Channels

4.3.Divergent Channels

4.4.Extraordinary Vessels

4.5.Network Vessels (Luo Mai)

4.6.Tendinomuscular Channels

4.7.Cutaneous Vessels

4.8.Cutaneous Regions

5.Psychoemotional Foundations of Veterinary Acupuncture

5.1.Animal Psychology in Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (TCVM)

5.2.The Effects of Points at the Psychological Level

5.3.Five Element Types in Dogs and Cats According to Their Emotional Behavior

5.4.The Role of Pathogenic Factors

6.Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine Diagnostics

6.1.Pathogenic Factors Diagnosis

6.2.Eight Principles Diagnosis

6.3.Organ Diagnosis

6.4.Six Levels Diagnosis (Shang Han Lun)

6.5.Four Aspects Diagnosis (Wen Bing)

6.6.Triple Burner Diagnosis (San Jiao Bian Zheng)

6.7.Channel Diagnosis

6.8.Five Basic Substances Diagnosis

6.9.Five Elements Diagnosis

7.Acupuncture Points

7.1.Transport Points

7.2.Phase Points

7.3.Ting Points

7.4.Xi-Cleft Points

7.5.Source Points

7.6.Network Points

7.7.Back Transport Points

7.8.Alarm Points

7.9.Meeting Points

7.10.Master Points of the Body Regions

7.11.Lower Sea Points

7.12.Points of the Four Seas

8.Point Selection

9.Point Identification and Needling

10.Forms of Acupuncture

10.1.Acupuncture Needles

10.2.Alternatives to Needle Acupuncture

II Atlas of Acupuncture Points

11.Lung Channel

12.Large Intestine Channel

13.Stomach Channel

14.Spleen/Pancreas Channel

15.Heart Channel

16.Small Intestine Channel

17.Bladder Channel

18.Kidney Channel

19.Pericardium Channel

20.Triple Burner Channel

21.Gallbladder Channel

22.Liver Channel

23.Governing Vessel

24.Controlling Vessel

25.Extra Points

26.Subject Index

27.Points Index

Foreword

I first met Dr. Christina Eul-Matern at a meeting of the German Society for Holistic Veterinary Medicine (Gesellschaft für Ganzheitliche Tiermedizin; GGTM) in Nuremberg in 2006. At that time, she was working with other colleagues to form the German IVAS Affiliate (GERVAS). I was impressed not only by her knowledge of acupuncture but also by her dedication in forming an organization that would provide acupuncturists in Germany with another avenue to meet and join forces in the promotion of acupuncture and Chinese medicine. Through her efforts and those of her colleagues, GERVAS is a young but strong and enthusiastic organization. She was also committed in providing a solid education of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (TCVM) and acupuncture to veterinarians and saw the IVAS-based curriculum model as ideal to teach veterinarians about TCVM and acupuncture in an organized, concise, and efficient manner, allowing veterinarians to complete the training within a year.

Dr. Eul-Matern remains committed to teaching and disseminating important information about acupuncture and TCVM, as evidenced by this atlas. Acupuncture for Dogs and Cats is well written, giving a concise but accurate review of TCVM and the bones of Chinese medical philosophy. Included in the first section are synopses of the Fundamental Substances, the zang fu organs—their relations to each other and their functions, primarily in accordance with the Five Element theory—and the various channel systems of the body. The author has distilled some of the most pertinent information regarding the Chinese understanding of medical physiology and has presented it in an easy-to-understand and relevant format. The TCVM diagnostics section is brief and to the point, again providing veterinarians new to the world of acupuncture with a handy “go-to” reference section to understand the various diagnostic methods and paradigms that exist in TCVM. Interspersed between the text are wellpresented drawings and tables that assist the reader in understanding basic and important concepts.

The second half of the first section of the book focuses on the acupuncture points that are most commonly used in animals today. Again, the author has successfully distilled the important characteristics and categories of points and their functions, beginning with an overview of various groupings of points and their functions and indications. The clear drawings accompanying this section of the book, which illustrate the location of these groups of points in relation to each other, are a very useful learning aid. The accompanying tables provide a quick and easy reference for veterinarians trying to categorize all of the new information regarding acupuncture.

The majority of the book focuses on the acupuncture points that are used in animals— their functions, locations, indications, and advice on needling techniques. Even the Chinese names and characters are given, something I have a personal interest in. What I find particularly useful about this atlas is that all the points on each of the channels are described. These include all of the transpositional points as well as some of the traditional points. The illustrations that accompany the point descriptions are impressive—not just in their quality but in showing the described points in relation to other nearby points. This is a great learning aid not only for new practitioners of veterinary acupuncture but also as a reminder for those of us with more experience.

It has been a pleasure to meet Christina and work with her on a limited basis, and I am honored that she asked me to write a foreword for her book. I had seen the atlas during courses in Germany and was disappointed that it was only available in German. Now this much-needed, concise reference book is also available in English and I would recommend it to any veterinarians learning acupuncture as well as to those with some experience. It will be a benefit to any veterinarian for years as they strive to understand all of the nuances of Chinese medical theory and how to use acupuncture to help our four-legged friends.

Linda Boggie, DVMIVAS Certified Veterinary AcupuncturistThe Netherlands

Preface to the Second English Edition

Because emotional factors are also highly relevant for illness in animals, I have decided to expand the third German edition of this book by incorporating the psychological effects of acupuncture points. Furthermore, I have added a chapter on the five elements and their connection to the psyche. This is intended to take into account an important aspect of animal acupuncture.

I want to take the opportunity here to thank Dana Müller who, as part of her acupuncture training, took all the illustrations to create a comprehensive chart for the cover pages, to offer a quick overview to the reader.

Christina Eul-Matern, DVM

Preface to the First English Edition

When a friend introduced me to Chinese medicine many years ago, my attitude toward holistic therapies changed rapidly. I had been conscious of the limited options for disease prevention in biomedicine for a long time and now seemed to have finally found a way to recognize health-related imbalances early on and even to avert disorders altogether. Countless scientific studies were able to substantiate this fact. For me as a veterinarian with a doctorate in Western veterinary medicine, this was great news. Research on topics such as the stimulation of vasoactive substances like serotonin, adrenaline, and endorphins or the effects of acupuncture on the autonomous nervous system aroused my interest.

Already during my training and even more so after years of clinical experience, after I began my activity as lecturer on animal acupuncture, discussions broke out again and again on therapies as well as point localizations. In this context it is important to know that in contrast to today, acupuncture in early China did not know of the exact point descriptions. At that time, it would be more accurate to speak of reactive areas than precise points. Even today, acupuncturists are still well advised to test the reactivity of an acupuncture point at the described location before needling it. To touch, palpate, and feel where the correct point is located, that is and remains an important aspect of acupuncture. The discussion on exact localizations is also kept alive by the fact that contemporary animal acupuncture in the West uses the two systems of transposed and traditional points side by side. Taking into consideration the physical changes in the course of evolution, the practice of transposing point localizations from the human body to the animal also contains a certain potential for variations. Animal acupuncture is increasingly being integrated into our Western healthcare system and scientifically examined and developed. Specialists all over the world are studying the effect, origin, and exact localization of individual points and exchanging their findings. The present work is an attempt to bring together all current information and tie it into a single atlas fit for the clinic. I have compared relevant information from the leading educational organizations and educators of animal acupuncture with the experiences from my own practice and taken this as a basis. This approach was utilized both for point localizations as well as for their effect and indications. In addition, for the effect and indications of acupuncture points, I have also taken into consideration the practical and Western-scientific experiences of modern animal acupuncturists.

Among all the possible justifications for the efficacy of acupuncture, however, one point is of particular importance to me: Acupuncture is an energy-based system of healing. All university education and long years of training in Chinese medicine do not change the fact that we bring our own energies into play when we practice acupuncture.

The literature on Chinese medicine contains numerous allusions to this factor: Needling techniques explain how we bring more or less qi into the organism or pull it out by changing the direction in which we twist the needle or the speed during insertion. Hand position (e.g., middle finger on HT-8) during needling is also meant to protect the practitioner’s own qi.

Good posture and attitude during needling are said to stabilize the practitioner and optimize treatment results.More than anything, though, a necessary prerequisite for any successful treatment is mutual trust, openness, and the willingness to help or be helped. I, therefore, appeal to anyone engaged in Chinese medicine and acupuncture to be attentive to the processes that take place on an energetic level and, if necessary, to continue training also in this area.

Now that Thieme Publishers has translated the pocket atlas Acupuncture for Dogs and Cats into English so soon after its German publication, I am overjoyed that this text will reach the international community of veterinarians and animal acupuncturists. I look forward to constructive pointers and collaboration.

Christina Eul-Matern, DVM

Acknowledgments

Here I want to express my gratitude to those without whose support this work would have never been possible in the first place, as well as to those who took charge so energetically of the English translation.

First of all, my thanks go to my students who pointed out again and again with matchless persistence the necessity of composing this atlas, thereby giving me the necessary motivation. Your ideas and suggestions were very useful.

Next, I want to thank my colleagues Dr. Brigitte Traenckner and Dr. Jean Yves Guray for having infected me with their enthusiasm for Chinese veterinary medicine and for giving me numerous new impulses, especially in the initial stages, which greatly accelerated my path.

I thank Christine Kinbach for her constructive suggestions for this book and for her consistent support, which has helped me along again and again.

In addition, special thanks go to my colleague Dr. Martina Steinmetz, who contributed greatly to the success of this book with her wonderful drawings, and to Suse Capelle, whose creativity has already helped me in so many ways. Her photographs of dogs and cats have become part of the foundations for this atlas.

I also want to thank Leon, our Podenco, for his patient collaboration and our kitty Smilla for her voluntary posing. You have done a fantastic job!

My dear family members, Hans-Karl, Anika, and Carina, deserve my deepest gratitude as well. They supported me and always granted me the space to work on this book in important moments.

I thank my parents who have always believed in me and have given me the feeling that everything that is truly important is within my reach.

Lastly, I thank Angelika Findgott and Anne Lamparter from Thieme Publishers, who have produced and optimized this wonderful translated edition with exceptional dedication and professionalism. For the translation itself, though, I have to thank Dr. Sabine Wilms. In an unparalleled manner, she has worked through, supplemented, and translated my writings, tables, and illustrations.

My heartfelt thanks to all of you!

Christina Eul-Matern, DVM

Note from the Translator

It is a rare treat for a translator to be involved in a project with as much personal appeal and connections as I have enjoyed in the present book. As a farmer and animal lover myself, I have been so happy to find Dr. Matern’s empathetic concern and experience in caring for our four-legged friends expressed on every page. As a lecturer and author on classical Chinese medicine for humans, I have found her clinical insights inspiring and her distinctly personal perspective refreshing, and I have been fascinated by her skillful integration of the traditional concepts of Chinese medicine with her clinical experience and modern scientific research. In my mind, the contents of this book and Dr. Matern’s style of veterinary medicine ultimately reflect the author’s understanding of the connections between humans and animals and the macrocosm at large.

It has been an honor to play a small part in bringing this book to the larger audience it deserves. My only hope is that the clinical advice contained herein will find abundant application, to the benefit of all the cats and dogs out there!

Sabine Wilms, PhD

I Basic Concepts of Acupuncture

1.What Does Acupuncture Have to Offer?

2.History of Acupuncture

3.The Principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine

4.The Channels

5.Psychoemotional Foundations of Veterinary Acupuncture

6.Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine Diagnostics

7.Acupuncture Points

8.Point Selection

9.Point Identification and Needling

10.Forms of Acupuncture

1 What Does Acupuncture Have to Offer?

Acupuncture is an energy-based system of healing that is several thousand years old and addresses and activates the self-healing powers of the body. Biomedicine therefore classifies it as a form of “regulatory medicine.”

The stimulation of acupuncture points influences the flow of energy within the body along the channels and hence in the entire organism. Acupuncture resolves blockages, moves stagnations, supplies emptiness with new energy, and relieves fullness. As a result, pain can be reduced and disturbed organ functions can be revived. Successful acupuncture restores the natural balance of the organism. It is not able, however, to heal permanently destroyed tissue.

One important aspect of this healing process is that the body learns through acupuncture to restore its balance on its own. The acupuncturist thereby has the role of showing the diseased organism the path to healing by means of the needle. Ideally, if identical problems reappear later, the patient’s self-healing powers will “remember” this path and start functioning on their own in the way that they have learned earlier.

During acupuncture treatment, fine needles are inserted at precisely localized acupuncture points and retained there for a certain amount of time. The length of time that the needles remain in the body depends on the indication and condition of the patient. To avoid injury to the underlying tissue and to nerves, blood vessels, joints, or organs, this treatment should only be performed by trained and qualified practitioners.

Animal acupuncture originally worked with individual, empirically discovered points and their combinations. A system of channels did not exist. This was only developed later, resulting in the systematization of animal acupuncture. This led to the development of the so-called “transposed system” of animal acupuncture, which differs from the classical points especially in the location of the back shu points. In the process of transposing, the location of these diagnostically and therapeutically useful acupuncture points was transferred from their location in the human body to their location in animals. The system was then refined further, primarily by medical doctors and later also by veterinarians. In clinical practice, veterinarians often supplement the transposed system with classical points of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (TCVM).

For the following disorders, TCVM and acupuncture can have a helpful or at least a supportive effect:

•Movement disorders; for example, due to arthrosis or arthritis in the hip, shoulder, elbow, knee, spinal column, and toes

•Growth and development disorders of the bones and joints

•Geriatric problems

•Chronic disorders of the respiratory tract, skin, gastrointestinal tract, urogenital tract, cardiovascular system, eyes, and ears

•Allergies and disorders of the immune system

•Hormonal disturbances, as in diabetes mellitus, Cushing’s disease, thyroid problems, ovarian cysts, and fertility disorders

•Epilepsy

•Tumors

•Psychological problems, such as pathological fears, aggression, etc.

At the same time, acupuncture can reduce the dosages of pharmaceutical drugs that may be necessary.

In all of these cases, the basic requirements for a successful treatment are a thorough medical history, examination, and diagnosis. The mere application of standardized needling formulas without knowledge of their background carries the risk of exacerbating the disorder and carrying it deeper into the body instead of improving or to say nothing of healing it.

The complex system of Chinese medicine was developed over several thousand years, partly on the basis of observations and experiences gathered and documented by individual practitioners. Over a long period of time, a large number of patients provided huge amounts of informative data. The evaluation of this material made it possible to discern general patterns that finally gave rise to a coherent medical philosophy. This philosophy aims at preserving the health of the individual by means of controlling and balancing actions on the inside and outside. Our Western knowledge of Chinese medicine and acupuncture is built on this groundwork, allowing for a well-informed application of acupuncture.

In my research, I have come across the following statement several times. I find it very meaningful and would therefore like to share it with you. The statement is from the preface of the extensively studied and often-cited classic Qian Jin Yao Fang (Essential Formulas Worth a Thousand Pieces of Gold) in which Sun Simiao (a Tang dynasty physician) describes the preparations required for anyone who wants to study medicine:

•“First, you must familiarize yourself with the Su Wen (Plain Questions), Jia Yi Jing (A-Z Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion), and Huang Di Nei Jing (Inner Classic of the Yellow Emperor) (three classic texts of Chinese medicine), the 12 channels, the Chinese pulse locations, the five viscera and six bowels (the internal ‘organs’ of Chinese medicine), the inside, the outside, the points, the medicinals, and the classic formulas.

•Additionally, you must understand yin and yang and acquire the ability to recognize life’s fortune (to read a person’s destiny from their face), to use the Yi Jing (Classic of Changes) (fortune-telling).

•You must know the meaning of justice, humaneness, and virtue. As well as compassion, sorrow, luck, and giving. You must also study the five phases of change as well as geography and astronomy ...”

These realizations are 1300 years old and still hold true today. Well-founded knowledge, life experience, and insight into human nature are indispensable for the correct evaluation of any state of health. Empathy, the desire to help, openness, and the willingness to give love are prerequisites for healing.

2 History of Acupuncture

To convey an impression of the time frame for the development of veterinary acupuncture, the following section lists some benchmarks:

In the Shang dynasty (1766–122 BCE), veterinary knowledge was documented for the first time. Inscriptions on bones describe disorders of both humans and animals. “Horse priests” used their healing powers to treat horses. One of their methods was the early use of the precursor of the modern Yi Jing (Classic of Changes). For this oracle, animal bones or turtle shells were heated and then interpreted by reading the resulting cracks.

During the Zhou dynasty/Chou dynasty (11th century to 476 BCE), the theory of yin and yang and that of the five elements was established. In this period, a large amount of veterinary knowledge was documented. As recorded in the historical text Zhou Li Tian Guan (History of the Zhou Dynasty), there were already full-time professional veterinarians. Another book from this time, the Li Ji (Book of Rites) describes the collection of medicinal herbs and also some serious animal diseases. The first veterinarian referred to by name was Chao Fu. The Huang Di Nei Jing (Inner Classic of the Yellow Emperor), which was composed in the Warring States period, states that acupuncture developed in Southern China, moxibustion in Northern China, medicinal therapy in Western China, and massage and acupressure in Central China. In this period, there were veterinarians who specialized in the treatment of equine disorders. Some of these books described various disorders of domestic animals. The needles used for acupuncture were made of iron.

During the Qin dynasty/Ch’in dynasty (221–209 BCE), the government issued laws governing livestock breeding and veterinary medicine, which is documented in the text Jiu (Yuan) Lu (Livestock Breeding and Rules of Veterinary Medicine).

In 1930, archaeologists discovered slips of bamboo in the desert of Western China that date from the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE) and contain formulas of medicinal therapy for animals. Some books from the time of Zhang Zhongjing (Zhang Ji) (about 150–219 CE) describe animal treatments that combine acupuncture and pharmacotherapy. There were also veterinarians specializing in cattle.

Around 500 CE, a training center and agency for veterinary medicine were established. Different books on veterinary medicine were composed.

During the Sui dynasty (581–618 CE), a government agency for veterinary medicine and livestock breeding (Tai Pu Si) was set up, subsequently employing 120 veterinarians. Several books were published on equine medicine, among them an atlas for channels and acupuncture for horses.

During the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), a comprehensive educational system for veterinary medicine was established. Between 705 and 707 CE, there were 600 veterinarians, four teachers, and 100 students at the Tai Pu Si. The Si Mu An Ji Ji (Collection of Ways to Care for and Treat Horses) is a book that systematically presents basic knowledge, diagnosis, and therapeutic techniques of Chinese veterinary medicine. In 659 CE, the government published the Xin Xiu Ben Cao (Newly Revised Materia Medica), which described 844 Chinese medicinal herbs for humans and animals.

During the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), Bing Ma Jian opened its doors as the first hospital for horses. They had so much work to do there that a plea went out in 1036 to consult other establishments for less serious cases. The famous veterinarian Chang Shun lived during this time.

In the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368 CE), Bian Bao wrote his famous book Ji Tong Xuan Lun (Treatment of Sick Horses).

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE), every owner of more than 25 horses had to provide two or three young men for the study of veterinary medicine. Many famous books on veterinary medicine were composed. Probably the most famous of these is the Liao Ma Ji (The Treatment of Horses), which was written by the Yü brothers after 60 years of clinical experience.

In the period from the Qing dynasty/Ching dynasty to the Opium War (1644–1840 CE), veterinary medicine developed little in China. We know of a few books on cattle diseases. In 1683, the German physician Dr. E. Kampfer (as did some French merchants at the same time) brought acupuncture to Europe.

Entering the Modern Age (1840–1949 CE), China had no interest in TCVM. Nevertheless, veterinarians kept it alive in their practice. Only two known books survive from this period—one on many types of animals including dogs and cats by Li Nanhui, and a unique book from 1900 on swine diseases, Zhu Jin Da Quan (Complete Collection of Swine Diseases), which contains 63 examples of complete formulas.

Western veterinary medicine (WVM) reached China at the beginning of the 20th century. A private school for WVM was opened in Shanghai.

Recent developments (1949 to present): The People’s Republic of China under Mao Zedong attempted to revive and develop TCVM and issued an edict on this matter in 1956. In the same year, the first National Congress for Popular Veterinary Medicine was held in Beijing. Here, participants were urged to combine Traditional Chinese with conventional Western medicine, in order to join the respective advantages of each system and to allow them to support each other.

Each therapy has its strengths and weaknesses. TCVM can treat disorders and thereby reduce sensitivity to certain disturbances. WVM has advanced diagnostic possibilities that can directly reveal the cause of a disease and pathogens. TCVM directs its attention to restoring the balance in the whole body so that it is better able to face stress factors and maintain its health. WVM addresses pathological symptoms and searches for causes in the form of agents, tissue injuries, dysfunctions, etc.

In the People’s Republic of China, training and research centers for TCVM were once again established. The publication of acupuncture analgesia has had a breakthrough effect, impressing Chinese and Western experts equally. New acupuncture techniques and formulas have been developed and as a result attention to acupuncture has grown tremendously since 1978.

Oswald Kothbauer from Grieskirchen in Austria was one of the first practicing Western veterinarians to apply acupuncture. He has written several scientific treatises on the subject of animal acupuncture and has thereby contributed to the development of this field in the West. Kothbauer was the first Western scientist who managed to perform acupuncture analgesia on a cow, the results of which he published in 1973.

Since the founding of the International Veterinary Acupuncture Society (IVAS) in the United States in 1974, veterinary acupuncture has developed rapidly all over the world, not least because of the founding of numerous affiliated national organizations.

In 2004, with the help of engaged colleagues the author was able to establish the first association of pure acupuncture veterinarians in Germany, the German Veterinary Acupuncture Society (GERVAS). Its objective is to promote the spread and quality assurance of veterinary acupuncture by means of qualified training and collegial exchange.

Today, we stimulate acupuncture points by a variety of methods. Different needles (steel, gold, silver, and platinum) are used (see Chapter 10, Acupuncture Needles), and laser, ultrasound, crystal, magnetic acupuncture, and moxibustion are examples of modern techniques in animal acupuncture (see Chapter 10, Alternatives to Needle Acupuncture). Acupuncture is known all over the world and has established itself in many countries. Veterinary universities and especially volunteer-led veterinary organizations have been engaged intensively in the development and training of Chinese animal acupuncture and medicinal therapy. The nonprofit organizations that currently offer state-certified training for veterinarians are the IVAS in the USA, Norwegian Acupuncture Society (NoVAS) in Norway, and the Akademie für Tierärztliche Fortbildung/Gesellschaft für Ganzheitliche Tiermedizin (ATF/GGTM) and GERVAS in Germany.

From 2016 to 2019, the author has been able to follow her colleague Detlef Rittmann in offering acupuncture/osteopathy as an elective to students in the School of Veterinary Medicine at the Justus-Liebig-Universität in Gießen, with an overwhelming response. The author is also teaching animal acupuncture as a lecturer at the Fresenius University of Applied Sciences in Idstein. Hopefully, these appointments are only a beginning and an important step for the acceptance of Chinese medicine. Individual veterinarians and alternative veterinary practitioners are also working successfully in this area. In order to promote the development of veterinary acupuncture and energetic veterinary medicine in this complex situation to the best of her abilities, the author decided in 2013 to establish a separate educational institute called VetSensus.

3 The Principles of TCM

3.1 Difference between Western Medicine and TCM

While Western medicine focuses on detecting and eliminating the cause of a disorder, Eastern medicine sees the origin of disease in the interaction of various, mutually interdependent internal and external influences. The Chinese physician looks for the threads that connect individual processes in the organism and merges them into one common effect. This is the point at which he or she recognizes nonphysiological patterns and shows the body the way back into healthy channels. Misdirected energies are steered back in the right direction, and the body is shown the way to self-healing.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the underlying goal is to integrate all the potential variables of a disorder into the patient’s clinical picture and include them in the treatment. This approach entails a direct contradiction to current research and treatment methods of Western medicine, whose goal is to control and, if possible, eliminate all variables. In individual cases, a deviation of symptoms from the norm can lead to problems with diagnosis or treatment.

Western medicine tends to analyze individual symptoms to understand the cause of a disorder. For this purpose, it has developed sophisticated diagnostic systems such as imaging techniques and laboratory diagnostics.

3.2 Important Terms in TCM

3.2.1 The Basic Substances

The five basic substances are:

•Qi (life energy)

•Xue (blood)

•Jing (essence)

•Shen (vital spirit)

•Jin ye (bodily fluids)

Qi

From the philosophical or cosmological perspective, qi is the true source of the entire universe and of life in general. It is the basic substance of which the world and hence also the human body is composed. It is only as the result of the tension between yin and yang that this activating energy in our world is created.

The body’s own qi moves the organism and, depending on its function, has different characteristics. To begin with, each organ and each functional cycle have their own qi with the specific characteristics required in that context.

In general, the functions of qi are:

•Moving

•Protecting

•Transforming

•Preserving

•Warming

In addition, there are different manifestations of qi in the body, which fulfill a variety of functions.

Zong Qi The respiratory or gathering qi is connected to the heart and lung. It gathers in the thorax and directs the rhythm of the breath.

Yuan Qi The source qi is the refined, energetic form of essence and has its source in the kidneys. It circulates in the body and activates all organs. It gathers in the yuan source points and courses through the triple burner.

Gu Qi The food qi is formed from ingested food by the spleen and then ascends into the thorax. There, it is transformed into blood in the heart and, in combination with air, forms the zong qi in the lung.

Zhen Qi The true qi is the last stage of refined qi and has two manifestations: wei qi and ying qi.

Wei Qi One aspect of qi which defends the body. It is the external protection (defense qi). Wei qi courses closely underneath the skin and regulates the sweat glands.

Ying Qi This is the nutritive qi that is linked to the blood (xue) and assists in transforming the purest nutrients into blood. Xue and ying are inseparable. “Battalion, barrack, camp, operational, searching” are translations for this term. All these terms are in the widest sense related to the notion of provisioning. Ying extracts itself and becomes blood. It nourishes the viscera and moistens the bowels. It originates from food (nutrients).

Xue

Xue is equated with blood. It is the material aspect of qi.

Jing

Jing (essence) is the earth aspect of the three treasures shen, qi, and jing, and thereby carries the greatest yin energy. Jing stands for the inherited substance/DNA and is an internally produced substance that should be preserved. Earlier heaven essence (xian tian zhi jing) is bestowed already on the fetus during conception and is very difficult to reproduce. It is consumed in the course of one’s life.

Later heaven essence (hou tian zhi jing) can be replaced daily by the spleen and stomach with a healthy diet.

Shen

Shen is the spirit, consciousness, vitality, or external manifestation of the internal condition of the body. Thinking is the dominant aspect of this concept. Shen manifests in the memory and in sleep, emanates from the eyes, and means “wonderful,” “mysterious,” and is related to the eternal dimension of life, to the magical and heavenly aspects of being alive. Shen is the yang aspect of the three treasures shen, qi,and jing. It connects us to heaven and brings us our dao.

Jin Ye

Jin ye are all the other fluids except for blood (xue). They are two completely different substances: Jin is a thin fluid that nourishes the skin and muscles and enters the blood. It forms sweat and urine. Ye is the thicker part that nourishes the bones, internal organs, brain, and marrow. It moistens openings and joints. Both of these come from the essence of our food.

3.2.2 Zang Fu

Zang fu is the Chinese term for the internal organs (Table 3.1). Zang are the visceral or storage organs. Fu are the bowels or hollow organs, which have the role of collecting and eliminating. The viscera and bowels are linked to the 12 main channels.

Table 3.1 Viscera and bowels

Viscera (yin)

Bowels (yang)

Liver

Gallbladder

Heart

Small intestine

Pericardium

Triple burner

Spleen

Stomach

Lung

Large intestine

Kidney

Bladder

3.2.3 Yin and Yang

Yin and yang are complementary opposites that form the basis of all phenomena and events in the universe. They are a developmental stage in the cosmological sequence.

Life means transformation. The monad tai ji (Fig. 3.1) symbolizes the relationship between yin and yang. The lower, black section of the circle symbolizes yin within yin, while the upper, white section stands for yang within yang. Both halves continuously change into each other and carry the seed of the other in them. We can see the polarity of yin and yang in animate and inanimate nature as well as in every living creature (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.1 Monad.

Fig. 3.2Yin and yang sides on the dog.

Originally, yin and yang were compared with the properties of the two sides of a mountain. The darker, cooler, lower side corresponded to yin; the brighter, warmer, upper side to yang. Consequently, yin was also associated with the sinking of fog, the condensation of water, slowness, stillness, gathering and containing, the inside, heaviness, depth, nurturing, the feminine, and the night. Yang, on the other hand, referred to warmth, dispersing, evaporation, activity, movement, speed, the outside, pushing, the masculine, and the day.

Heaven (seat of the sun) is yang; the earth is yin.

Functions of Yang

•