1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

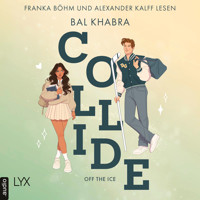

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

In "An Outlaw's Diary: Revolution," Cécile Tormay presents a compelling narrative that intertwines the personal and the political, offering readers a raw and unfiltered account of life during times of upheaval. Written in a vivid, confessional style, the book serves as a stark portrayal of the tumultuous events that define revolutions and their impact on individuals. Tormay's meticulous attention to detail elevates her prose, creating a haunting atmosphere that invites the reader to immerse themselves in the chaos and emotional turmoil experienced by the protagonists. Through lyrical language and poignant reflections, the work critiques the often-glamorized notion of revolution, exposing its harsh realities and the moral ambiguities that accompany it. Cécile Tormay was a prominent Hungarian writer and political figure, having lived through significant historical contexts that shaped her worldview. Her experiences during the early 20th century's societal transformations, as well as her roles in the arts and activism, definitely informed her literary pursuits. Tormay's formidable intellect and deep empathy for humanity are woven throughout her work, making her reflections on revolution both personal and profound. "An Outlaw's Diary: Revolution" is a must-read for anyone interested in the intersection of literature and politics. Tormay's insights into the human condition during revolutionary times offer readers an opportunity for deep reflection on the nature of change and conflict. The book not only stimulates critical thought but also evokes profound emotional responses, making it a significant addition to the canon of revolutionary literature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

An outlaw's diary: revolution

Table of Contents

PREFACE

It was fate that dubbed this book An Outlaw’s Diary, for it was itself outlawed at a time when threat of death was hanging over every voice that gave expression to the sufferings of Hungary. It was in hiding constantly, fleeing from its parental roof to lonely castles, to provincial villas, to rustic hovels. It was in hiding in fragments, between the pages of books, under the eaves of strange houses, up chimneys, in the recesses of cellars, behind furniture, buried in the ground. The hands of searching detectives, the boots of Red soldiers, have passed over it. It has escaped miraculously, to stand as a memento when the graves of the victims it describes have fallen in, when grass has grown over the pits of its gallows, when the writings in blood and bullets have disappeared from the walls of its torture chambers.

And now that I am able to send the book forth in print, I am constrained to omit many facts and many details which as yet cannot stand the light of day, because they are the secrets of living men. The time will come when that which is dumb to-day will be at liberty to raise its voice. And as some time has now passed since I recorded, from day to day, these events, much that was obscure and incomprehensible has been cleared up. Yet I will leave the pages unrevised, I will leave the pulsations of those hours untouched. If I have been in the wrong, I pray the reader’s indulgence. My very errors will mirror the errors of those days.

Here is no attempt to write the history of a revolution, nor is this the diary of a witness of political events. My desire is only that my book may give voice to those human phases which historians of the future will be unable to describe—simply because they are known only to those who have lived through them. It shall speak of those things which were unknown to the foreign inspirers of the revolution, because to them everything that was truly Hungarian was incomprehensible.

May there survive in my book that which perishes with us: the honour of a most unfortunate generation of a people that has been sentenced to death. May those who come after us see what tortures our oppressed and humiliated race suffered silently during the year of its trial. May An Outlaw’s Diary be the diary of our sufferings. When I wrote it my desire was to meet in its pages those who were my brethren in common pain; and through it I would remain in communion with them even to the time which neither they nor I will ever see—the coming of the new Hungarian spring.

CECILE TORMAY.

BUDAPEST,Christmas, 1920.

FOREWORD

The writer of this book tells us that “here is no attempt to write the history of a revolution, nor is this the diary of a witness of political events.” Nevertheless the fact remains that it contains much more than the personal experiences of an actor in one of the greatest tragedies that has occurred in recent history. If it were only that, its value would still be very great, for it is so vivid and dramatic a human document, and yet its style is so simple and so completely devoid of all “frills” or straining after effect, that it will appeal as much to those who like good literature and a moving tale for their own sakes, as to those who desire to understand a chapter of history about which little is known, but which yet throws a flood of light upon the great world movements of to-day.

To those who are interested in that international revolutionary movement which, in one form or another, is threatening every civilized state to-day, this book will be invaluable. The course of events which led up to the revolution in Hungary was precisely similar to the course of events in Russia. In both cases there was a more or less open radical, socialistic, and pacifist movement working in conjunction with a hidden subversive movement. In Hungary the latter movement is described as “a pseudo-scientific organization of the Freemasons, the International Freethinkers’ Branch of Hungarian Higher Schools, and the Circle of Galilee with its almost exclusively Jewish membership.”

In both cases the way for revolution was prepared by an insidious propaganda in the workshops and in the Army and Navy. In both cases the revolution was not the result of a spontaneous outburst of popular feeling but of a sinister conspiracy using the confusion and discouragement of a military disaster for its own ends. In both cases the first step towards the complete overthrow of Church and State was the erection of a bourgeois radical and socialist republic whose aim was to disintegrate and demoralise as a preliminary to the coup d’état which ushered in “the dictatorship of the Proletariat.” Russia had her Kerensky, Hungary her Károlyi.

This book deals with Hungary’s agony from the standpoint of one who experienced every one of its phases; it does not deal with Hungary’s resurrection from the grave of Bolshevism, and it is here that the parallel with Russia ceases. The heart of Hungary was sound; the corruption, demoralisation and inertia which have made Russia the plague-spot of humanity had not so deeply permeated the national life of Hungary. The race had too much vigour, too great a regard for its religion, its history, its traditions and its liberty to submit for long to that soul-destroying tyranny. And yet—and here is a lesson for the countries of Western Europe—this nation, which, owing to its traditions and the character and pursuits of its people would have seemed less disposed than any other to submit to Communism, did for a time succumb to the despotism of a few criminal fanatics, a gang of mental and moral perverts. And the disaster was due not so much to the strength of the subversive influences as to the weakness and cowardice of the authorities in Church and State and in Society at large.

In a great industrial country like Great Britain there is far more favourable ground than there was in Hungary for the production of antisocial philosophies and the manufacture of revolutionaries; the danger from insidious propaganda, from the failure of Government to govern, is no less but rather more than it was in Hungary. This book shows how appalling are the consequences of even a temporary overthrow of those bulwarks of civilisation, law, order and religion, and that mankind in the 20th Century is capable of reverting in a moment to the barbarism and anarchy of the Dark Ages. Russia, Italy, Hungary and Ireland have all in the past few years told the same tale. One of the greatest empires of the world now presents the picture of a society enduring a living death; Hungary and Italy have saved themselves by their exertions and perhaps Europe by their example. Ireland’s fate is trembling in the balance, but the corruption of a whole population, the systematic training of the youth of a country to exalt rebellion into a science and murder into a religion, can only have one result. If the cancer has been checked in some quarters, if the gangrene has been amputated here and there, the poison is still working through all the European body politic, not only in those outrageous forms which naturally arouse opposition in all decent and educated minds, but in those subtle forms which disguise themselves under the cloak of a spurious Christianity, a zeal for humanity, the brotherhood of man, and the internationalism of Labour. The open and the hidden agitations subsist side by side and each plays into the other’s hands. The “Red” International of Moscow, the “Yellow” International of Amsterdam, the various shades of Socialism and Syndicalism, are all parts of one great subversive Movement though their adherents are not all aware of it, and the strings are pulled by the Secret Societies which during the past century have been behind every revolution in Europe.

And, as this book reminds us, the only means of counteracting the danger is not by surrender or compromise, not by seeking new creeds and theories but in adherence to old ones, not by nursing illusions but by facing facts, by courage, by a steadfast regard for principles, by the faith of authority in its mission, by “strengthening the things which remain and are ready to die.”

NORTHUMBERLAND.

AN OUTLAW’S DIARY

CHAPTER I

October 31st, 1918.

The town was preparing for the Day of the Dead, and white chrysanthemums were being sold at the street corners. A mad, black crowd carried the flowers with it. This year there will not be any for the cemeteries: the quick adorn themselves with that which belongs to the dead.

Flowers of the graveyard, symbols of decay, white chrysanthemums. A town beflowered like a grave, under a hopeless sky. Such is Budapest on the 31st of October, 1918.

Between the rows of houses shabby, drenched flags wave on their staffs, and the pavement is covered with dirt. Torn bits of paper, pieces of posters, crushed white flowers mixed in the mud. The town is as filthy and gloomy as a foul tavern after a night’s debauch.

This night Count Michael Károlyi’s National Council has grasped the reins of power.

So low have we fallen! Anger and inexpressible bitterness assailed me. Against my will, with an irresistible obsession, my eyes were reading over and over again the inscriptions on strips of red, white, and green paper which were pasted on the shop windows in unceasing repetition: “Long live the Hungarian National Council”.... Who has wanted this council? Who has asked for it? Why do they stand it?

Count Julius Andrássy, the Monarchy’s Minister for Foreign Affairs in Vienna, was clamouring desperately for a separate peace. The thought of it raised in my mind the picture of some distant little wooden crosses.... As if they came down from among the clouds.... Graves at the foot of the Carpathians, on the Transylvanian frontier, along the Danube. Fallen in the defence of Hungarian soil....

And now we forsake the mothers, wives and children of those who are buried there. The blood rushed to my face. Everything totters, even the country’s honour. The very war-news fluctuates wildly. Our heroes gain tragic, profitless victories on Mount Assolo, whilst on the plains of Venezia the army is already in retreat—along the Drina, the Száva and the Danube too. And here in the capital the soldiers are swearing allegiance to Károlyi’s National Council. What a mean tragedy! And over the empty royal castle, over the bridges, on the steamers on the Danube, flags are flying as if for a holiday.

I reached the Elisabeth Bridge. In irregular ranks disarmed Bosnian soldiers marched past me, most of them carrying small military trunks on their shoulders. The little wooden boxes moved irregularly up and down in rhythm with their steps, which had lost their discipline. The soldiers cheer and cannot understand what it all means. But for all that: “Zivio!” They are allowed to go home, so they are going towards the railway station.

A motor lorry came up the bridge towards me. The electric trams have stopped, and the whole road belonged to the lorry. It raced along furiously, noisily, like a crazy wild animal that has escaped captivity. Armed young ruffians and soldiers stood on it, shouting; and a boy, looking like an apprentice, lifted his rifle with an effort and fired it into the air. The boy was small, the rifle nearly as long as himself. Everything seemed so incredible, so unnatural. One of the Bosnians appeared to think so too, for he turned back as he went along. I can see him now, with his prematurely aged face under the grey cap. He shook his head and muttered something.

Then the Bosnians disappeared. The damp wind blew cold from the Danube between the houses of Pest, and the rain started again.

At the corner, three men were gathered under a single umbrella, their big boots looking as if they stood empty in the water on the road. Their coats too looked as if they were empty, and the water drizzled from their worn-out hats on to the collars of their coats. Clearly they were petty officials. For thirty years and more they have been accustomed to go at this time of the day to their office. Now they have found suddenly that the path has slipped away from under their feet, and they don’t know what to do: this was an unlawful business ... the official oath ... their conscience.... If it were not for the question how to live! What about the others? Perhaps they have gone already. One ought to take counsel with the head of the department....

They discussed the matter, started to go, stopped, then started again. Finally, when I looked after them they were walking on steadily, as if they had found the accustomed groove from which it was impossible for them to swerve.

Posters, fastened to poles, were floating in the air. Underneath, in a steady throng, people passed incessantly, walking as if under compulsion, as if they could not stop, as if they had lost the power of altering their direction. It was as though some huge dark animal crawled along the pavement, a yoke on its neck, and as it crawled slowly it cheered.

I felt an inarticulate cry rising in my throat, and I wanted to shout to them to stop and to turn back. But in the flowing crowd there was already something like predestination, something which cannot be stopped. And yet occasionally its course was deviated. The throng parted now and then, and in between motor cars passed in regular, short jerks. And in the cars, decorated with national coloured ribbons and white chrysanthemums, were typically Semitic faces. Behind them, in the middle of the road, the human waves closed up again.

I turned off into a by-street. A peasant’s little wooden cart came towards me. Swabian peasant women from Hidegkút were being shaken about in it, gay and broad among the milk cans. Suddenly—I did not notice whence they came—three sailors stepped into the cart’s path. One caught hold of the horse’s bridle while the two others jumped on to the cart. Everything happened in a flash.... At first the women thought it was a joke, and turned their stupid young faces to each other with a grin. But the sailors meant no joke. With curses they pushed the women off the cart and, as if they were doing the most natural thing in the world, in broad daylight, in the middle of the city, and in sight of a crowd of people, they calmly drove off with somebody else’s property. The whip cracked and the little cart went off in rapid jerks. Only then did the women realize what had happened. With loud shrieks they called for help and pointed where the cart had gone to. But the street was lazy and cowardly and did not come to the rescue. Men passed by, shrinking from contact with other people’s troubles, as if these were infectious.

It was all so helpless and ugly. It seemed to me that all of us who passed there had lost something. I dared not follow up the trend of my thoughts....

Under the porch of the next house two ruffians attacked a young officer. One of them had a big carving knife in his hand. They howled threats. A stick rose and the lieutenant’s cap was knocked off his head. Dirty hands snatched him by the throat. The knife moved near his collar ... the stars were cut off it. The cross of his order and the gold medal on his chest jangled together. The mob roared. The little lieutenant stood bareheaded in the middle of the circle, his face as white as snow. He said nothing, did not even defend himself, only his shoulders shook convulsively. With a clumsy movement, like a child who starts weeping, he passed the back of his left hand across his eyes. Poor little lieutenant! I noticed now that his right sleeve was empty to the shoulder.

Even then nothing happened. The people again pretended not to see, as if they were glad that it had not been their turn.... Everything seemed confused and vague, like a half-waking fever-dream in the reality of which the dreamer does not believe, though he cannot help moaning under its influence.

What was happening there?... In front of the Garrison Commander’s building, under some bare trees, some soldiers were holding open a large red, white and green flag. At first I thought they were at play. Then I saw that an unkempt, bandy-legged little man was cutting out the crown from above the coat-of-arms with his pocket-knife. And they held it out for him!... I felt as if I had been burnt, and turned my head away so that nobody might see my face. A little further on the declaration of the Social Democratic Party stared at me from a wall:

“Fellow workers. Comrades! The egotism of class rule has driven the country with inevitable fatality into revolution. The troops who have joined the National Council have occupied without bloodshed the principal places of the capital, the Post Office, the Telephone Exchanges and the Town Hall, on Wednesday night, and have sworn allegiance to the National Council. Workers! Comrades! Now it is your turn! The counter revolution will undoubtedly attempt to regain power. You must demonstrate that you are on the side of your soldier brethren. Out into the streets! Stop all work!

The Hungarian Social Democratic Party.”

This poster made a curious impression on me: it was as if a monstrous lie had proclaimed the truth about itself. The party which was striving for the rule of the working-class orders in its first declaration: “Stop all work!” After such a beginning, what will it order to-morrow—and after?

People came towards me: workmen who were not workmen, who no longer do any work; soldiers who were not soldiers, who no longer obey. In this foul atmosphere nothing is any longer what it seems. The many red, white and green flags on the houses are no longer our flags; no longer are they the nation’s colours. Only the chrysanthemums remain true flowers of the graveyard.

I went on slowly, but suddenly I stopped again: on the glass window of an obscure little tobacconist’s shop, among the newspapers exposed for sale, appeared a sickly, crushed-strawberry coloured poster, which proclaimed in red “Long live the National Council.” And then, as if some loathsome skin-disease had infected the houses, appeared more and more red posters, and their colour became bolder and bolder. I was informed later that panic-stricken tradespeople had paid two hundred crowns, some even a thousand, into the funds of the National Council for this shop-window insurance.

In the windows of some shops the big poster of the Népszava[1] was displayed. In one night the organ of the Social Democrats had penetrated from its slum into the city, and its poster proclaimed from the windows of meek bourgeois shops “Behold the writing!” ... On the poster was printed in red a naked man lifting his red hammer at the crowd beyond the window. A horror made of blood.... The thronging crowd never thought that the hammer was lifted to break its head. And the tradesmen never thought that the hairy red hand was on the point of emptying their tills. I noticed that on the poster of evil omen, besides the bloody monster, a red working-man was struggling with a policeman who held him in chains.

A curious picture.... I now thought of the police of the capital. The day before yesterday it had adhered to Károlyi’s National Council. The famous police force of Budapest had forsaken its high ideals of duty and had gone over to the wreckers. Never before did I realize the importance of this betrayal. I shivered. The fog drifted as if the very atmosphere had become unstable. The walls of the houses near me seemed to waver too; and I seemed to hear the cracking of the plaster, as if they also were preparing to collapse. The noise came from the very foundation of things. Something invisible was collapsing in this city already undermined.

“Hungarians” ... then silence. A little further it went on: “National” ... then it started again all along the street. My unwilling eyes were reading the posters over and over again.

“National Council”.... What is this obscure assembly after all? How dare it call itself the council of the nation? Who are those who incite against the state and collect oaths of allegiance for themselves? Who are those who from the room of an hotel appeal to the nation and promise “an immediate Hungarian peace, the equal right of all nations, the League of Nations, the freeing of the world, a social policy which will strengthen the power of the workers”?... They have not got a word for our frontiers established a thousand years! What happens in the background whither our eyes cannot penetrate? Do the secret allies of the Entente work among us, or only our own enemies who, by means of their proclamations, shout in their Ghetto-lingo that “this programme, which is to save Hungary and free the people, has the whole-hearted support of the Hungarian army?”

Who says that? Who proclaims himself the saviour of Hungary in the hour of her greatest peril? Count Michael Károlyi and Rosa Schwimmer? Martin Lovászy, Baron Louis Hatvany-Deutsch, John Hock, Sigmund Kunfi-Kunstätter, Ladislaus Fényes, William Böhm, Count Theodor Batthyány and Louis Bíró-Blau? Dezsö Abraham, Alexander Garbai and Ernest Garami-Grünfeld? Oscar Jászi-Jakobovics, Paul Szende-Schwarz and Mrs. Ernest Müller? Zoltán Jánosi, Louis Purjesz and Jacob Weltner?

Eleven Jews and eight bad Hungarians!

My soul is racked with indescribable pain. Good God, where is the King? Where is Count Hadik and his government, the officers, the still faithful troops? Are there no longer any fists? Is there nobody to strike at all?

After Gödöllö the King now gropes in Vienna. Hadik remains inactive while the fateful hours fly by. The officials do not lay down their pens, but incline their heads meekly under the new yoke. And, worst of all, the military command surrenders its sword without an attempt to draw it. There is no resistance anywhere: dark, underhand forces by careful labour have prepared the ground long ago. They have demolished everything that is Hungarian. And now, one stitch after the other, with deadly rapidity, the fabric that has endured a thousand years is coming undone.

My brain worked feverishly, thoughts galloping madly and seeking desperately for somebody—something. Somebody who could still stem the general ruin. Stephen Tisza!... And silently I asked his pardon for having condemned and misunderstood him. How he must suffer now! What must his thoughts be?

Near the church of the Franciscans a thronging crowd pushed me to the wall, so that I could not move. In front of me small urchins wormed themselves like moles through the crowd—Galician boys, with payes—locks hanging down in front of their ears—who were present and yet invisible, whose passage was only signalled by the shrinking of people’s shoulders, just as the underground road of the mole is marked by the mole-hills above. The boys were distributing poetry printed by the Népszava, offering it with humble impudence and thrusting it into the pockets of those who refused to take it.

The air was full of disturbing noises, and cheering was audible from the end of the road. A motor lorry clattered towards the Town Hall, reeling sailors, armed to the teeth, standing upon it with wide-spread legs. Red ribbons floated from their overcoats, and they bellowed songs. A schoolboy was running after the lorry dragging a big rifle behind him on the pavement. Soldiers, students, ragged women, streamed along. In the uproar two gentlemen were pushed to my side near the church wall. One was extremely excited: “I know it from a quite reliable source,” he said. “They are looting in the suburbs. The stores too.... Yesterday Károlyi’s agents armed the workmen of the arsenal. Thirty thousand armed workmen! At the railway station the mob has disarmed the soldiers.”

“There is not a word of truth in all that,” answered the other. “There is order everywhere. Post Office, telephone exchanges.... The railway-men have declared for the National Council. The whole press is with it, and so is public opinion.... The situation has been quietly cleared. As soon as Károlyi’s government is formed there will be order ... Lovászy, Kunfi, Jászi, Garami.... We must resign ourselves. None but Károlyi can get us a speedy good peace.”

“How do you know?”

“Well, the newspapers.... Then Károlyi has made a statement. He has great connections with the Entente.”

REVOLUTIONARY SOLDIERS.

(To face p. 8.)

I lost all patience and could listen no more, so sought a passage in the crowd. The throng became thinner, and a drunken soldier staggered past me. An officers’ patrol came out from a street and stood in the soldier’s way. Every man of it was a Jew. One of them shouted harshly: “In the name of the Soldiers’ Council!” and the drunkard submitted reluctantly.

Now I remembered: some days ago I had heard that Károlyi’s men were organizing soldiers’ and workmens’ councils. These councils meet in conclave at night in schoolrooms, lecture halls. And this in Hungary! Here, in our midst ... I shuddered from head to foot. “In the name of the Soldiers’ Council!” It seemed as if Trotski’s Russia had shouted into the streets of Pest.

Near my head a half-torn poster rustled in the wind. “To the Nation.”... Tattered, Archduke Joseph’s cry of alarm died on the grimy wall. I looked quickly behind me. Does anybody besides me read it? No, nobody stops. And yet, how many people were about? And the crowd increased. It was as though the city had for years devoured countless Galician immigrants and now vomited them forth in sickness. How sick it was! Syrian faces and bodies, red posters and red hammers whirled round in it. And freemasons, feminists, editorial offices, Galileans, night cafés came to the surface—and the ghetto sported cockades of national colours and chrysanthemums.

As though it were beneath some wicked enchantment, the invisible part of the town has now become visible. It has come forth from the darkness to take what it has long claimed as its own. The gratings of the gutters have been removed. The drains vomit their contents and the streets are invaded by their stench. The filthy odour of unaired dwellings spreads. Doors are thrown open that till now have been kept closed.

Russia! Great, accursed mystery.... Did it begin there in the same way?... I breathed with repugnance and drew myself together so that none might touch me in passing.

Presently I met an armed patrol. Though the soldiers wore ribbons of the national colours I still felt a stranger to them, for they have already sworn allegiance to the National Council.... They looked shabby and bore chrysanthemums in the muzzles of their rifles. From a window a woman of Oriental corpulence threw white flowers to them.

A young girl came along, a Hungarian. She distributed chrysanthemums and smiled, and her shaded eyes shone like a child’s: “Long live independent Hungary!” I stared at her. There are some like this too. Many, perhaps very many. They live the glorious revolution of 1848 in this infamous parody, and dream of the realization of Kossuth’s dreams. Poor wretches! They are even more unfortunate than I am.

The girl offered me a flower and talked some nonsense about Petöfi. I wanted to tell her to give it up and go home, that she had been deceived and it was all lies; but my efforts were in vain, I could not pronounce a single word. I stumbled over the edge of the pavement, my feet seemed leaden.... A bucket stood in front of me with a big brush in it. I looked up. A weedy youth was spreading paste over the wall, and a new poster glared at me. The people stood around and craned their necks.

“Soldiers! You have proved yourselves the greatest heroes within, the last twenty-four hours, don’t soil the honours you have gained.... Abstain from intoxicating liquors.... Obey your comrades who have volunteered to maintain order. With patriotic, cordial greetings,

Heltai,Town Commandant.”

“And who is that, now?” people asked each other.

“The Commander of the troops?”

“Is he the Heltai who is the son of Adolph Hoffer?”

“To be sure!” I heard behind my back.

The unkempt crowd laughed.

“Paul Kéri and Göndör got him nominated by the National Council.”

Paul Kéri, whose name used to be Krammer, and Francis Göndör, whose real name was Nathan Krausz, two radical newspaper scribes, decide who is to command the troops of the Hungarian capital! And it is on Heltai, the son of Adolph Hoffer, that their choice falls.

VICTOR HELTAI alias HOFFER,REVOLUTIONARY COMMANDER OF THE BUDAPEST GARRISON.

PAUL KÉRI alias KRAMMER,ONE OF COUNT KÁROLYI’S ADVISERS.

(To face p. 10.)

Wild fury, hopeless despair, came over me. I wanted to shout for help, like the Swabian women whom I had seen robbed. But who would have listened to me and my misery? They might have laughed, or they might have arrested me. The street moved, lived, hummed, but it was not conscious. For a time I stared at the people, then I set my teeth. Was it I who was mad, or they? And I went on.

In front of the Astoria Hotel the crowd stopped. After its secret sittings in Count Theodor Batthyány’s palace Károlyi’s National Council pitched its tent here, till it might take possession of the conquered Town Hall. Near the hotel innumerable carriages and motors were waiting. Flags flew from the building and through its revolving door, which reminded one of a bank, men of the stock-exchange type went in and out. There was no policeman anywhere, though the crowd was increasing dangerously. The monster which had crawled in from the suburbs was reclining against the wall of the building, leaving a muddy, smirched trail behind it. Its head rose under the porch: a man stood on the others’ shoulders. His face was red and he waved his hat violently as he shouted:

“Hadik has got the sack.... Károlyi is Prime-Minister!”

“Somebody is going to make a speech,” a little Jew girl said and tried to press forward. Over the porch an ugly fat man appeared between the flags. “Eugene Landler!” shouted the girl in rapture. A soldier thrust her aside. “What’s he got to do with it? In the barracks, last night, those who spoke were at any rate Hungarians—a chap called Martin Lovászy and one called Pogány. They had darned big mouthpieces, but they had the gift of the gab!”

The crowd hummed like a boiling kettle. “Speak up, hear! hear!” All looked upward.

A voice from the porch fell into the listening ears. I stood far away, on the other side of the road, so only incoherent words reached me:

“... an independent Hungary ... democracy ... social reforms.... International platform.... In the interest of foreigners.... The gentle-folk have driven us to the slaughter-house!”

“Well, that’s just the place for that fat one,” said the soldier with disgust. Those near him began to laugh, and a man who appeared to be an artisan screwed up his lips and gave a shrill whistle.

“That’ll do. Say something new! Shut up!” some shouted towards the porch.

Then something unexpected happened. A young Jew threw the name of Tisza into the crowd. He threw it there, just as if by accident.

“He caused the war! Long live Károlyi! To death with Tisza!” The same thing was shouted from the other corner, and a hoarse voice exclaimed:

“Long live the revolution!”

I shuddered. It was for the first time that I heard it thus, openly, in the street. Rigid white faces appeared under the entrances. But the cry died away. It found no echo.

“Down with the King!” This appealed to the mob. It was new, hitherto none had dared to touch this. The rabble snatched at what it heard and vomited it back with a vengeance. And the repulsive chorus was led by the young man who had previously mentioned the name of Tisza.

The news-boys of a mid-day paper came shouting down the street: “The National Council has proclaimed the Republic!”

“Long live the Republic....” This was only an attempt, but it failed. Nobody became enthusiastic. Someone shouted: “To Gödöllö!”

A Versailles, à Versailles! The starving mob of Paris shouted this a hundred and thirty years ago, and now in Budapest fat bank clerks exclaim: “Let us go to Gödöllö!” Nobody moved. It is said that ten thousand armed workmen are marching on it.... I burned with shame. This news was not invented by Hungarian minds. Armed men, against children! It is not true.... At any rate, the King’s children have made good their escape.... I only heard half of what was said. Poor little children!...

EUGENE LANDLER,HOME SECRETARY. LATER A COMMANDER IN THE RED ARMY.

(To face p. 12.)

As if I had been chased I turned to go down the boulevard towards the bridge. By now armed sailors were already stopping motor-cars in the streets, thrusting the occupants out and driving off in the cars. It was done quickly. Big lorries filled with armed soldiers raced across the bridge. Some were even hanging on to the steps. Shots were fired, and a drunkard sang in a husky voice: “Long live the Revolution, long live drink....”

The whole thing was humiliating and disgusting. If only I could escape from it, so that I might see nothing, hear nothing! I longed for home—home, out there in the woods, among the hills.

At the entrance of the tunnel that passes under the castle hill a soldier was offering his government rifle for sale and asking five crowns for it. Another offered his bayonet.

On the other side of the tunnel I felt as if I had emerged at the antipodes. There the town was quiet, so quiet that I could hear the echo of my steps in the streets of Buda. The single-storeyed houses cuddled peacefully on the side of the hill. There people will not know what has happened till to-morrow, when they will read it over their breakfast.

In one of the low windows some flower-pots stood between the curtains. A clock struck in the room, and a young girl started watering the flowers with a little red watering-can. Doubtless she watered them yesterday at the same hour and life will be the same for her to-morrow. Meanwhile, on the other bank of the Danube they shout: Long live the revolution! Revolution.... Madness! What good can a revolution do now? Nobody takes it seriously, not even those who made it. Madness! It did me good to repeat the word, and I began to take heart. Nothing will come of it. The Hungarian is not a revolutionary—he fights for freedom. Every commotion in our history of a thousand years has been a war of liberation. And freedom has come: independence has fallen from its own accord into the nation’s lap....

A light already shone in one of the little houses. Under the hanging lamp, round a circular table, people sat peacefully. They knew of nothing.... In one of the yards someone played an accordion. The homely, suburban music, the fatigue of my long silent walk, weakened the awful impressions of the other shore. All that had tortured me was disappearing, and my thoughts were only of hanging lamps and accordions.

The density of the mist increased with the evening, and when I reached the old military cemetery it had nearly absorbed the outlines of all objects. Over the collapsing graves, between the many little rotting wooden crosses, the tombstones dissolved like ghosts in the fog. In Pest by now the mist would be a yellow reeking fog, while here it became a thing of beauty. Nowadays everything that is beautiful in the country turns to filth in Pest.

Again I forgot to pay attention to the road, and my thoughts harped on what I had lately seen.

It was impossible that a few slums of a single town should make a revolution when the whole country was against it.... Then, I don’t know how, I came to think of The Possessed—Dostoevski’s wonderful novel. I remembered a reception which I had attended last winter. We talked of Russia, Lenin and Bolshevism, and I asked one of Michael Károlyi’s relations if Károlyi had ever read that book.

“Of course, and he loves it, too. He lent it to me to read.”

There had been curious rumours about Károlyi for some time.

“Is he learning from it how to make a revolution?” I asked, but received no answer.

I was tired and walked on slowly. Along the road the old, leafless chestnut trees came towards me in hazy monotony, and there recurred to my memory the little Russian town in Dostoevski’s book, into which with his genius he has crowded a picture of Russia as a whole. Young revolutionaries, back from Switzerland, meet accidentally in the little town. The demoniacal leader of these morbid youths, craving for power, destroys the existing order and produces chaos. Consumptive students, alcoholics, syphilitic degenerates, prospective suicides, cracked intellects, murderers and despairing cowards gather round him and he forms a group of five from the select. And then he convinces them that innumerable similar groups are waiting with eagerness for the signal to revolt. When his five men hesitate he tricks them to commit a murder, so that the knowledge of common guilt should make his slaves mutually suspicious of each other. At his order they will raise the pyre.... The actors of the revolution are together and the primal conditions are ready. And then dissolution, terror and panic will come, and the frightened, despoiled people will be prepared to suffer anything and to recognise anybody as their omnipotent master who can create order, whatever that order may be. “We take the sly ones with us, and lord it over the simple.” That is the idea of Dostoevski’s hero. The eleven internationalists of the National Council think the same. They too share the power with the cunning ones and use Károlyi as a stepping-stone to power. After all Károlyi is nothing but the tool of this Council. Who the demon is, I do not yet know.

Up, to power.... But they will not get it! A few resolute officers with a handful of soldiers can restore order. The National Council is nothing but an isolated “group of five.” There are no others. If its members are arrested, the mud they have stirred up will settle down; they are not united by any common honour, by any common crime.

Napoleon once said that with a few guns he could have stopped the great French Revolution. For these, a volley of rifle fire would do. But where is he who can command it to-day?

I came to the bridge over the Devil’s Ditch. In the mist the bridge looked as if it did not rest on the banks. Above the depth of the fog it floated mysteriously in space. Behind a drab amorphous veil the forest on the slope of the hills seemed a dreamy enigma; the trees by the road: lacelike blossoms of mist on the background of the falling night.

No sound reached me. Only some pebbles, displaced by my steps, clattered behind me. A branch cracked in the forest; it made me think of a skeleton wringing its hands in impotent despair.... And if they don’t arrest Károlyi and his accomplices to-night? Dostoevski’s novel came again to my mind and from among my thoughts there emerged the shout of a wicked, shrill voice: “To death with Tisza!” The penetrating mist now chilled me to the marrow. I felt cold all through.... “Death to Tisza!” It rang in my ears all the time. Good God, for how many years has this savage cry been prepared by blinded politicians, by frivolous political salons, by nearly all the press, in barracks, in factories, in the aula of the University, in the market place, between cellar and attic, in every human den! For how many years! The work was done by ruthless agitators, and now it is crowned with an awful success. In the eyes of the crowd he would not be a criminal who attempted the life of Tisza. His life is outlawed. The crowd is already prepared for the event. The mob in the street may clamour without risk or protest for the life of this man: “To death with Tisza!” I could not stop the fearful cry from ringing in my ears.

For days I had spoken to nobody who belonged to Tisza’s circle. Was he in town? Had he gone? If only he had gone away!... And I walked along the mountain path while the hoarse cry followed me, like a vagabond with evil intent. Try as I would I was unable to shake it off.

Night had fallen and the mist had become dense round our house. The fort opposite had disappeared and the edge of the mountain had become invisible. From far away, in the direction where the town lay, the report of firearms was audible.

In the cold darkness the house appeared so lonely, as if it had been expelled from communion with the rest of the world. The bonds that had tied human fates together have been severed, and we know of nought but what is going on in ourselves. The house was enclosed in a huge, grey wall of mist.

In the hall I tried to telephone, but could get no answer from the exchange. The receiver buzzed meaninglessly.

All at once rifle shots sounded from the hills, then came nearer. Suddenly a shot rang out at the bottom of our garden. Another. That one was nearer. Then a bullet struck the chestnut tree under my window. It had a curious effect upon me, for an instant later it seemed as if the whole thing had happened to someone else—as if I did not really live it, but just read about it in a book.

I extinguished the lamp, so that my lighted window should not serve as a target, and then groped my way in the dark to the ground floor, to my mother’s room. A narrow band of light showed on the floor under the door. As she was awake I went in. She was sitting quietly in one of the uncomfortable, high-backed, old-fashioned chairs. At the sound of the opening door she turned and our eyes met. For a time we remained silent. The firing outside had stopped too.

“They seem to have stopped shooting,” said my mother, after a while, in that wonderful quiet way which was always reflected on her countenance whenever life treated her harshly.

“It will be over sometime; we’ve got to live through it somehow,” I said, just to say something.

My mother moved wearily. “Be careful you do not catch cold. The night is cool ...”

Suddenly there was a sound of voices on the road. I remembered something I had been told. Burglars....

“We ought to hide our money, mother, at any rate. If it were taken we could get no more under the present circumstances.”

For a moment, a moment only, my mother looked at me with consternation. Then: “Of course.” And her mind too had crossed the abyss that separated the old world of safety and protection from the new world of insecurity, lawlessness, and uncertainty.

I slipped the money under the carpet in the dark hall. Twice I stopped. Someone was speaking in the road, near the gate. Voices were audible, long consultations.... Steps withdrew. I went carefully up stairs and took care that nobody should observe that the house was awake.

My room seemed to have become chilled while I was downstairs. The blackness engulfed me as in some deep black sea, and I shivered. For a long time I remained standing in the same place. An incessant sound of death came to me from outside: the chestnut tree under the window was shedding its leaves. Resignation. The time of many falling leaves. The eve of November.... The air was filled with low, rustling, soughing, ghostly sounds. It was as if a crowd walked stealthily in the garden and the forest stole secretly away.

Hopeless distress, as I had never felt it before, came over me. Autumn is departing from the hills this night, and by the morrow it will be gone. Then winter comes irresistibly, dragging at its heels snow, cold, frost, suffering, the unknown and perhaps the impossible.

What is in store for us?

In the darkness, like the ticking of time, incessantly, the leaves fell with a faint sound. A dog whined beyond the garden, whined in an eerie, terrifying way, as if somebody had died in its master’s house....

Despair overcame me. It was not only a dog that whined its lament: it was the night that wept over Hungary.

CHAPTER II

November 1st.

In the morning I heard that Tisza had been murdered.

The telephone rang in the corridor, sharply, aggressively, as if the town was shouting out to us among the woods. It was with reluctance that I put the receiver to my ear.

The ringing stopped and I heard only that meaningless buzzing at a distance. It lasted for some time while I stared through the window at the little ice-house in the garden. At last there was silence and I recognised the voice of my brother Géza. He spoke from town, enquired after mother, and asked how we had passed the night. In town they had been shooting all night long, and armoured cars had rushed through the streets. And then he said something I could not understand clearly.

I felt a strange reluctance to understand. I began to be afraid of what was coming, of hearing something which, once known, could never be altered again. The presentiment of catastrophe took possession of me.

“But what happened?”

“Poor Stephen Tisza....”

I still looked out into the garden at the reed-thatched roof of the ice-house, staring at a reed which had become detached by some winter storm. I stared at it till my eyes ached, as if I were clinging to it. It was only a reed, but now everything to which one could cling was but a reed. Suddenly the garden vanished. The window disappeared, and tears fell from my eyes.

I heard the voice of my brother again. He concluded from my silence that I had not understood what he said, so he repeated it: “He is the only victim of the revolution. Soldiers killed him. They penetrated into his house and ... in the presence of his wife and of Denise Almássy they shot him dead.”

“The scoundrels!”