Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

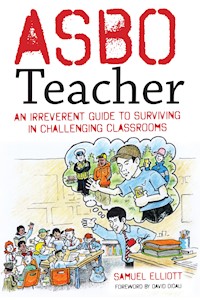

Foreword by David Didau. Samuel Elliott has been the pupil from hell. He knows what he needed from his teachers in order to turn his life around - and in this book he shares that knowledge with hard-pressed colleagues who just want to do their best for their pupils. In ASBO Teacher Samuel offers no-nonsense principles hewn from the chalkface of the modern British classroom: ideas and approaches that have worked for the author in the most challenging settings and with the most testing pupils. Covering a range of issues spanning behaviour management, lesson structure, resource preparation and narratives in the classroom, the book is a blueprint for becoming a particular kind of teacher - one who has high expectations, a concern for pupil well-being, and a knack for ushering learners into more effective learning. (Note: ASBO stands for 'antisocial behaviour order', a legal order in the UK issued to restrict an individual aged ten or above from harassing or causing alarm or distress to other people.)

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A

PRAISE FOR ASBO TEACHER

Filled with truth, ASBO Teacher illuminates the reality of modern-day teaching with vivid and visceral clarity. At times shocking and at others downright hilarious, Samuel’s revelations are always insightful and carefully disseminated, taking in both the bigger picture and the finer details of education theory.

This is not just an enthralling account of one young teacher navigating his way through the comprehensive system; it is also filled with invaluable advice for others who are attempting to do the same.

CHARLIE CARROLL, AUTHOR OF ON THE EDGE

ASBO Teacher is the educational equivalent of a Bear Grylls survival guide, with particularly insightful tips on effective classroom management. It offers an informative view that details why pupils often misbehave and provides a fantastic array of practical strategies and approaches that any teacher can pick up and run with. The anecdotes and stories embedded into the book also give the issues at hand true relevance and are easy to relate to.

A cracking read and a must-have book for any classroom teacher.

SAM STRICKLAND, PRINCIPAL, THE DUSTON SCHOOL, AND AUTHOR OF EDUCATION EXPOSED AND EDUCATION EXPOSED 2

Samuel Elliott’s ASBO Teacher takes us on a whirlwind tour of the modern British education system that is hair-raising, eye-opening, and hugely entertaining.

For those embarking on a career in the inner-city classroom this book is surely an invaluable resource, an essential guide, and a compendium of ‘everything you need to learn about teaching that the establishment may never teach you’. I hope many new teachers educate and entertain themselves by reading it.

MELISSA KITE, CONTRIBUTING EDITOR, THE SPECTATORB

The subtitle of this book calls it irreverent, but to label it wholly as this does it a disservice. It is crammed full of brilliant behaviour management strategies that are rooted in research, psychology and Samuel’s own experience, giving teachers a unique insight into why kids might misbehave and what they can do about it.

This book won’t help you turn kids into robots, but its useful realism will genuinely help improve your behaviour management skills. What is more, it is written by someone who is still in the classroom, walking the walk. I will be recommending ASBO Teacher to everyone.

HAILI HUGHES, TEACHER, CONSULTANT, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR OF MENTORING IN SCHOOLS

C

FOREWORD

I was something of a toerag when I was at school. (Some might tell you I still am, but they didn’t meet me back then.) I skived almost all of what is now referred to as Year 9 and, when I did put in an appearance, I was lazy, uncooperative and a royal pain in the arse. That said, I was more of a class clown than a thoroughgoing ne’er-do-well. In my favour, I was very good at seeming contrite. My head teacher once told me that, of all the boys he’d had to sanction, I was always the sorriest. I left school with three substandard GCSEs and a determination never to set foot in a school again.

My naughtiness pales into laughable insignificance when contrasted with the tales of terror Sam Elliott tells of himself. Sam’s story is utterly compelling. His journey from ASBO to teacher, and thence to ASBO Teacher, is very different to my own. Unlike Sam, who seems to have turned himself around in remarkably short order, I spent many long, rather pathetic years in a wilderness of heroin addiction and petty crime before eventually cleaning up in my mid-twenties. I would like to say that I took to teaching like a duck to water, but that would be a lie. It would be closer to the truth to say that my relation to my chosen career was more that of an abandoned shopping trolley dumped in a fetid pond. Like many new teachers, I experienced much of the ritual harrowing that Sam describes in this book and, through a long and bitter struggle, I carved out a stern teacher persona that meant I could begin to teach in a way that meant a precious few of my students got at least something worthwhile from their education.

It is utterly depressing to think that this trial by terror is still a routine occurrence for too many teachers. Some time ago, I described successful teachers surviving – occasionally thriving – in broken schools as warlords in a failed state. Despite the chaos raging around them, their classrooms are bastions against barbarism and oases of sweetness and light. As you will see, Sam has taken on this mantle with pride. His stories of classroom life are both an inspiration and a source of despair. ii

The fact that so many schools continue to be such unwholesome places in which to work or learn is very much a cause for despair. After a break of eight years gallivanting around the country as a Z-list edu-celebrity, I am now back in the classroom teaching English part-time in three different schools. Each of the schools in which I am fortunate enough to work have committed to eliminating low-level disruption. Each school has challenging intakes and, in each, teachers have been forced to tolerate appalling levels of defiance and disrespect because those responsible for setting the school culture shrugged their collective shoulders, sheepishly shook their heads and asked, ‘Well, what can you expect from kids like these?’

But in each of these schools a quiet revolution is underway. Robust systems are now in place which ensure that teachers can teach and children can learn. There is a better way. This undiscovered country is no Shangri-La. Schools up and down the country are working out that having high expectations for students’ behaviour is not just possible; it is – for all its challenges – vastly easier than the alternative.

But for those teachers condemned to work in schools where leaders have abandoned the belief that ‘kids like these’ are capable of behaving with even minimal levels of politeness and respect, hope is in desperately short supply. Lack of collective responsibility ensures that the system chews through bright young teachers, spitting out their desiccated husks as the twin demands of unsustainable workloads and viciously unacceptable student behaviour take their toll. ASBO Teacher is a survival guide for working with challenging students in challenging schools and, as such, is a beacon burning in the darkness and will provide much-needed succour and support for those who need it most.

But this book is more than a mere candle in the wind. It is a riveting read and – more than a few times – laugh-out-loud funny. The stories of the students and colleagues Sam has had the pleasure (and misfortune) to teach and work with jump from the page with ringing authenticity. You can imagine yourself in his classroom, laughing at his jokes and being desperately keen to win your very own Geography Ambassador badge. This isn’t all. ASBO Teacher is steeped in a deep understanding of the complexity of education. Sam talks readers through many of the thorny issues confronting iiiteachers – differentiation, classroom organisation, workload, assessment – and, with commendable honesty and openness, attempts to pick a way through the tangles of competing claims to arrive at workable solutions.

Bullshit is as rife as ever in schools and this book provides a much-needed tonic. As your guide and fellow traveller, Sam is a wonderfully subversive staffroom crony, muttering beautifully timed comic imprecations, just as the assistant head in charge of teaching of learning spells out what new balderdash is expected of teachers in the term to come. If you work with challenging students in a school where students are failed by inadequate leadership, you could do worse than become an ASBO Teacher yourself.

DAVID DIDAU BACKWELL iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In register order, a big thank you to Teiga Clarke-Phillips, Nathan Cornwall, James Croissant, David Didau, Rebecca Elliott, Wilson Gill, Melissa Kite, Ben McIlwaine, Jake McIlwaine, Matt Perryman, Samuel Pollard, Ben Stockton, Nathan Tyson, and Gurpreet Virdee. And, of course, Emma Tuck and everyone at Crown House Publishing. vi

CONTENTS

x

INTRODUCTION

There is too much information in the teaching profession, much of which is either flawed, contradictory, or stultifyingly boring. I don’t see why this should be.

If I want to drive a car, I am taught simply and directly to apply the clutch, to change gears gently, and not to careen around cyclists. By contrast, in teaching, all we are really offered are Barnum statements. Popularised by circus ringleader P. T. Barnum, these are the very general, seemingly prophetic insights offered by mystics, fortune tellers, and astrologists. An example would be, ‘You are having problems with a friend or relative’, which could apply to anyone. Barnum statements are also what mentors and managers will offer you in those vital few moments after asking you, ‘So, how did you think that went?’

Some will tell you that you ‘need more engagement’, maybe observing that ‘Billy is being disruptive’. Others will ask you with a wry, knowing smile, ‘How could you have made that easier for yourself?’ thereby hoping to invoke the spirit of group work from your lips. Other popular trivialities include: ‘You’ll get there’, ‘Try using mini whiteboards’, or, if things are truly desperate, ‘Have you ever tried using lollipop sticks to call names out?’1 I’m only surprised that nobody has asked me to ‘await patiently the alignment of Jupiter and Saturn’, and yet I think that these bland snippets of unobjectionable advice are even less useful than that.

Now, I am convinced that while every teacher will have his or her own preferred style, there are certain dos and don’ts of the profession. And I believe that these apply universally. What I offer in this book are principles that you can choose either to adopt or discard. If you were to adopt all of them, you would become a particular kind 2of teacher – one who has high expectations, a concern for pupil well-being and a fearsome reputation. But I expect that this ‘menu’ will be more à la carte than that.

Why is there a need for this book? Well, you are going to be given a number of contradictory messages over the course of your career. Take seating plans: at the time of writing, the dogma has it that they should be mixed ability. However, my belief is that children should be seated so as to minimise disruption, and pupil data gives us very little indication on how disruptive a pupil can be. Maybe when psychologists invent an NQ, or naughtiness quotient, we can use data from the school information management system (SIMS) to reliably seat individual pupils. Until then, you have no choice but to go into a room and decide the plan for yourself.

There are no quick fixes, but like chess there are certain strategies you can use, such as the Spanish Opening, along with positions you will want to avoid, like checkmate and hanging pieces. This book will not tell you how, where, and why to do X, Y, and Z, but it will give you the educational version of a Spanish Opening, helping you to anticipate mistakes before making them and thus to gradually improve over time.

In Chapters 1–3, I examine effective behaviour management through the narrative lens. Inevitably, these chapters are autobiographical. The stories are all true and pupil dialogue is verbatim, although I have done the literary equivalent of putting the names and places through a blender, siphoning out extraneous fluids, while retaining the salutary pulp and fibre. In the remaining chapters, I offer the principles distilled through practice. The offerings here are more concentrated. I take counterintuitive principles from my own career and attempt to stir and shake them into the heady cocktail of contemporary educational research. Whether or not I’ve succeeded, I shall leave to the reader to decide. 3

WHY ASBO TEACHER?

The concept came to me one morning in the humanities staffroom as my ‘Stone’ computer whirred and clanged into fitful inactivity. A boot-up so excruciatingly slow that it was barely keeping pace with its brand name; to call the process ‘geological’ would be a slander on sedimentary rocks everywhere. My colleague was talking about a book he wanted to write called ‘Vampire Teacher’. I’d explain the premise, but I don’t have access to a campfire and the radiator doesn’t quite cut it. That was when I thought of ASBO Teacher.

But who, or what, is an ASBO Teacher? Rewind to 2007. I was in Year 10. You would find me in the park with twenty of my mates, downing vodka like I wanted to high-score the breathalyser and chain-smoking enough to contribute appreciably to climate change. I couldn’t have cared less about my education. I lived in the pub that my parents ran in one of the rougher areas of Coventry, and this gave me seemingly infinite scope for mischief. For instance, in the summer of 2007, I set up my own bootlegging enterprise, where I’d fill up one of those giant four-litre squash bottles with random squirts from various upside-down spirit bottles at the bar – no half measures here. Every time I made this concoction, it turned chalk-grey, then white, and then the kind of green that looks like it should glow in the dark but disappointingly didn’t. No idea why it turned out this way; maybe something to do with the combination of Pernod and cordial. Next thing you know, kids from all over Coventry would be lining up to pay me for samples of this choice vintage, since it saved them from waiting for half an hour outside Bargain Booze.

In another of my extracurriculars, I found an old cigarette machine lying forlorn in a brambly allotment behind the pub car park, and resolved to break in and have what was inside. It wasn’t quite Ocean’s Eleven, but it did involve a blowtorch, an empty beer keg, and a steel baseball bat. Once I’d battered the front in, the machine disgorged hundreds of old cigarette packs, and I scooped them into a Tesco carrier bag. I spent the whole of Year 10 selling these for £2 each, managing to make a few hundred quid. Every little helps. It was tough at first because these cigarettes weren’t in packs of twenty, but in the unusual denominations of seventeen or fifteen 4– apparently so they could fit in the machine. When everyone trusted me that the cigarettes were ‘legit’, they paid up because, again, it cut out the caprices of whatever patron saint was currently in charge of getting served.

Ten years later, I’m a teacher. I’m reading a book called On the Edge by Charlie Carroll, a supply teacher who requests to be sent to Britain’s toughest schools. Carroll visits Nottingham, Sheffield, and London, and has to deal with all manner of abuse. One particularly cheeky chappie named Ralph makes his feelings clear, ‘I’m gonna smash that fucking posh twat’s face in! Fucking following me everywhere, the gay prick!’2 It’s like Notes from a Small Island if Bill Bryson got told to fuck off every seven pages. Nobody ever helped Carroll, and it’s a shame because there are effective strategies. You’ll be told that it’s all about your teaching, and that’s partly true, but behaviour management is the precondition.

The moral question that Carroll’s story raises is simply this: ‘What is a teacher to do?’ When I was at school, I remember one occasion when I had beaten somebody up for beating up one of my friends; these sorts of tortuous casus belli were as much a feature of teenage altercations as of the Peloponnesian War or the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The next day, there were older cousins at the school gates ready to ‘bang me out’. I needed a detention – fast. So, I shouted, ‘Miss!’ and tore up my friend’s planner so thoroughly that many would consider me an early pioneer of GDPR.3 Suitably detained, my teacher went to the office, and I sat there terrified, watching the clock. I was nervous; testosterone coursing through my veins like antifreeze. But, hey, at least I was in a detention, safe, with the teachers in the nearby maths office.

But at 3.25pm, the classroom door thwacked open and in poured about twenty lads, none of whom had even attended the school, many of them brandishing scooter helmets. Not a teacher in sight. I had a sneaking suspicion that at least one of the teachers in the maths office must have known about this incursion, but if they did, they prudently kept out of it. Fortunately, these lads had all been 5expelled from school before they could develop anything approaching even basic initiative, and their only plan had been for me to have a rematch with the kid I’d already beaten up. I said, ‘Why? I’ll just beat him up again.’ They thought about it, a few of them nodded, and some bright spark opined that I should at least apologise. ‘Sorry,’ I said. That was it.4

I could well imagine my maths teacher walking in during this face-off between me and the Mensa Youth – and what could she have done? She could probably have given ‘partial agreement’, a strategy advocated by Bill Rogers.5 ‘Why, yes, you should beat up this pupil, but maybe let him wear one of the helmets, and only from the neck down.’ She might have been in favour of that.

So, what is a teacher to do? And where does ASBO Teacher come in? Two words: Frank Abagnale. In Catch Me If You Can, Frank forges cheques, impersonates airline pilots, and makes a lot of money.6 But it couldn’t last forever. Eventually, he’s captured by the FBI, imprisoned, and later recruited by the FBI’s bank fraud unit. His former lifestyle gave him an invaluable insight into the psychology of scam artists and con men. As a result, he was very successful.

How I came to be a teacher, I shall never know. Fate? Or maybe the scientologists are right and it was all those negative orgones I racked up as a teenager. Either way, just like Frank could identify a counterfeit from its pigments and resins, so I know every bluff, trick, and prank in all of the unwritten Haynes Manuals of pupil disruption. Is it about poverty? No. The richer my family were, the more money I had to spend on ASBOlogical appurtenances like Bacardi Breezers and Adidas hoodies. The parents, then? Well, my mum was a striver who had worked hard to earn a scholarship to private school. She was from a background so poor that my nan, instead of buying her new joggers for PE, would crochet additional length onto the trouser cuffs. Consequently, she was always banging on about university. 6‘But students are wastemans,’ I’d point out. ‘Why the fuck would I wanna go uni?’ I didn’t know any Latin otherwise I could’ve capped it with a ‘QED’. So, why are pupils badly behaved? The answer is the seemingly paradoxical answer that there is no answer. I could give you something specious like the Edmund Hillary rationale: ‘Because it’s there’.7 But the truth isn’t quite so intrepid. I was just a Cov lad who couldn’t give a fuck.

To give you an idea, one Friday I had been getting drunk at the Forum – more high street and bowling alley than toga and chariot, although Caesar could just as well have been stabbed there. There had been complaints about us from the locals. I’m not surprised: there were about 200 of us hanging out along the 100-metre stretch between Bargain Booze and KFC. All in tracksuits, drinking something that looked like radioactive waste, with many parked up on mopeds and road-legal dirt bikes. Later that night, I was wrestled into a police car by two officers and delivered back to the pub. These were the days before Uber so I suppose I owed them a fiver.

On Monday, everybody at school was talking with admiration about how I’d been grappled by two police officers. ‘They couldn’t get him in the car,’ said one. ‘Trust me, my brudda’s on a big man ting.’ Thankfully, none of them saw the crocodile tears in the back seat that diverted the officers from their original destination of Chace Avenue Police Station.

The same scene played out every fortnight or so, until one day, two police community support officers tricked me into signing a yellow form. I thought it was some kind of well-being survey. Next thing you know, there’s an ‘ASBO caseworker’ ringing my mum. ‘What’s an ASBO?’ I asked, as all the bar staff fell about in crumpled postures, laughing. ‘Antisocial behaviour order,’ the barman said. ‘Basically, the government wants you to stop being such a little knobhead.’ Outside of a Mike Skinner concert or fire sale at JD Sports, ASBOs were one of the few ways of keeping the yobbos off the streets. It’s why the police were so keen on chauffeuring me home every Friday night.

7Is this anything to be proud of? Not really. It is simply my equivalent of the senior leadership team’s (SLT) youthful dalliance with bell-bottoms and platform shoes with dead goldfish inside. Back in the 1970s, when Mr Blockhead was out every Saturday doing his best John Travolta impression, the only professionals he was concerned with was a television show where the young Judge John Deed runs into abandoned warehouses with a sawn-off shotgun every week. When there was an oil crisis so severe it meant people had to cut back on everyday essentials like hairstyles that didn’t grow down over their ears. Then, in an unforeseeable turn of events thirty years later, a 12-year-old rapper named Little T would singlehandedly rehabilitate the perm.8 ‘His lyrics leave much to be desired, so it’s hard to see why it caught on again.’ With lyrics like that, it’s easy to see why it caught on again. No longer the preserve of Liverpudlian carjackers from the 1980s, the cycle of idiocy has come full circle. But I am part of this cycle, and I do not pretend otherwise. I boast of my youthful antics in the same way that Mr Blockhead might reminisce about his denim shirt with the pointy collar and the satin tiger stitched on the reverse.

Thinking back over these events, I’ve thought of a useful rule for enforcing discipline within the comprehensive education system. I was reading a book called The Learning Rainforest by Tom Sherrington. He talks about ‘rainforest teaching’, which comprises 80% knowledge teaching and 20% opportunity for more experimental, group-based activities.9 So far, so good. However, although he has worked in challenging schools, throughout the book he mostly refers to King Edward VI Grammar School (KEGS), and says that, ‘Once you have met students with an extraordinary work ethic or students who can dazzle you with their insights and imagination … you see possibilities for learning that you can never unsee.’10 While Sherrington makes a convincing case for rainforest teaching, he also notes that in ‘more challenging contexts’ there are 8several benefits to what he calls ‘plantation thinking’.11 This is where the school environment is more strict, controlled, and authoritarian. The purpose is to provide ‘a safety-net that seeks to ensure that every child gets a solid curriculum experience’.12 I contend that in certain communities, plantation teaching is more appropriate than its rainforest counterpart. This is because of what I call the disadvantage–strictness ratio: in short, tougher areas require tougher schools.

Back when I was a pupil, the only thing I could dazzle you with was the headlamp of an unregistered moped. For me, teachers had to be strict because I didn’t have any cultural capital outside of school – unless the Walsgrave Bargain Booze has recently been classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In exploratory or group-based learning activities, I’d draw more blanks than a mime artist with an invisible paintbrush. And what I needed most was to be drilled with the propositional knowledge that I wasn’t getting anywhere else. This is not to blame my teachers. Everything I did in Year 10 was my own fault and falls squarely on my own shoulders. But there are still kids like me in schools today, and if we’re asking in a strictly logical sense, ‘How do we get them from A to B?’ this is how: (a) direct instruction that is knowledge-based, and (b) zero-tolerance disciplinary measures. I know that only these two in conjunction can bridge the yawning crevasse of social disadvantage.

At the moment, we have to be cautious in how we implement findings from cognitive psychology, since in some schools there is an implicit trade-off between learning and behaviour. Here’s one example: ‘A workable solution for individual teachers is to vary seating plans as much as possible [since] changing the physical and emotional context even to this small degree can disrupt students’ ability 9to recall and transfer [information].’13 David Didau and Nick Rose argue that disrupting certain short-term cues can boost learning over the long term. However, I can think of many classes where a high number of disruptive pupils means there’s only one workable seating plan. If I were to vary my seating plan, chairs would be flung, rulers snapped, and projectile fidget-spinners embedded in the walls. To a lesser extent, the same is true of other findings such as interleaving content; it would work at KEGS, but it makes naughty kids less confident and thereby increases disruption. Currently, our expectations of pupil behaviour are lower than fracking equipment, and the only way to implement research-based ideas wholesale is for us to deal with naughty children, either by being strict, removing them from circulation, or through dedicated isolation facilities.

Why are some catchments worse than others? It has much to do with a culture of honour in what we call rough areas. According to Steven Pinker, cultures of honour ‘spring up when a rapid response to a threat is essential because one’s wealth can be carried away by others’.14 Where do we find them? Typically, in ‘urban underworlds or rural frontiers or in times when the state did not exist’.15 As deprived as some areas of Coventry and Birmingham are, they’re nothing compared with the blood feuds of the American West, or the Yanomamö tribesmen of Venezuela who routinely cleave each other with machetes over marriage rights. There is a continuum between honour cultures and those known as ‘dignity cultures’, where ‘people are expected to have enough self-control to shrug off irritations, slights, and minor conflicts’.16 Deprived urban areas exist closer 10towards the honour end of the spectrum than areas in wealthier catchments.

How does this affect our practice? In higher socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds, parenting can be either authoritarian or permissive, but lower SES parents are ‘typically authoritarian’, reflecting the social reality of a childhood that is ‘rife with threat’.17 This is why telling professionals to nurture children can be damaging. In tougher areas, Sweet Valley High sentiments not only transform standards into limbo poles, they mark out professionals as outsiders: soppy individuals, almost foreign in their naiveté, who can be terrorised with impunity. At the moment, these teachers try desperately to ‘engage’ city kids with gimmicks – an egregious example being Nando’s-themed ‘takeaway’ homeworks, where pupils are asked to try at least one ‘extra-hot’ task, along with whatever ‘mild’ and ‘medium’ tasks they see fit. All this shows is that you’ve never been to a Nando’s before: when did you last ask for a medium butterfly chicken and have the waiter raise an eyebrow before telling you, ‘That’s a bit low on the Peri-ometer’? As Tom Bennett puts it, ‘engagement is an outcome, not a process’.18

In this book, I’m providing a set of tips, tricks, and heuristics (rules of thumb) that I have gleaned from my ASBO apprenticeship, my close reading of the literature, and my first four years of teaching. The word ‘authority’ has many political connotations. Full disclosure: I am not a conservative. The appeal of Boris Johnson has always eluded me. And as for military investment, if you like looking at missiles and army helicopters so much, try Airfix. Neither is this some sergeant-major manifesto for shouting at children. My solutions are more nuanced than you might expect for an author who has already managed to hit just about every hot button going before clearing the introduction.

My final piece of advice before reading this book is to understand that if you’re working in the comprehensive system, the social rules, 11norms, and even aspirations are starkly different from schools in wealthier areas. I’m not suggesting you rail-grind a BMX into the school reception on your first day or that you spit some bars about spits and bars, if geography is your thing. What I am saying is that if you are going to change the culture in these schools, you need to learn elements of the culture in order to understand how not to get terrorised, and the weapons that initial teaching training (ITT) currently equips you with are as useful as a KFC spork in the midst of The Hunger Games. Read the book, observe fellow professionals, and try these tricks for yourself. Enjoy.

1 Daisy Christodoulou explains that the implementation of these ‘surface features’ of Assessment for Learning (AfL) were far from Dylan Wiliam’s original intention in their side-by-side interview for Carl Hendrick and Robin Macpherson (eds), What Does This Look Like in the Classroom? Bridging the Gap Between Research and Practice, Kindle edn (Woodbridge: John Catt Educational, 2017), loc. 561.

2 Charlie Carroll, On the Edge: One Teacher, A Camper Van, Britain’s ToughestSchools, Kindle edn (London: Monday Books, 2010), loc. 2407.

3 General Data Protection Regulation.

4 Or so I thought. Ten years later I would see one of them in a presentation on why we shouldn’t exclude pupils. He’d been sent to prison for putting drugs up his bum.

5 Shaun Killian, My 5 Favourite On-the-Spot Behaviour Management Strategies from Bill Rogers, Evidence-Based Teaching (22 November 2019). Available at: https://www.evidencebasedteaching.org.au/bill-rogers-behaviour-management.

6Catch Me If You Can, dir. Steven Spielberg (DreamWorks Pictures, 2002).

7 Technically, George Mallory first said it: Forbes, ‘Because It’s There’ (29 October 2001). Available at: https://www.forbes.com/global/2001/1029/060.html#397284ad2080.

8 Also known as the ‘Meet Me at McDonald’s’ haircut – it’s the kind of hairstyle that kids who meet up outside McDonald’s invariably have.

9 Tom Sherrington, The Learning Rainforest: Great Teaching in Real Classrooms (Woodbridge: John Catt Educational, 2017), pp. 142–143.

10 Sherrington, The Learning Rainforest, p. 41.

11 The term is an unfortunate one since it inspires the intellectual sloven to cries of ‘slavery’. I leave the rebuttal to social psychologist Erich Fromm: teacher–pupil authority is ‘the condition for helping of the person subjected’, whereas slave-owner authority is ‘the condition for exploitation’. This is the difference between ‘rational’ and ‘inhibiting’ authority. I argue in favour of the former: see Erich Fromm, The Sane Society (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2002 [1955]), pp. 93–94.

12 Sherrington, The Learning Rainforest, p. 41. This is not to say that I agree with the full definition of ‘plantation’ outlined on p. 39; I mean it entirely in the sense that teachers acknowledge a ‘right way of doing things’ and not interventions, accountability to external agencies, or the increased status of data.

13 David Didau and Nick Rose, What Every Teacher Needs to Know AboutPsychology (Woodbridge: John Catt Educational, 2016), p. 67.

14 Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works (London: Penguin, 1999), p. 497.

15 Pinker, How the Mind Works, p. 497. Another theory is Robert Putnam’s social capital – ‘a sense of trust and cooperation and common interest’ – which is lacking in these communities. Since Putnam’s theory applies just as well to wealthier areas, I have chosen to ignore it. See David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics (London: Penguin, 2017), p. 110; and Brian Keeley, Human Capital: How What You Know Shapes Your Life (OECD Insights) (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2007), p. 102. The relevant subsection of chapter 6 headed ‘What is Social Capital?’ is available at https://www.oecd.org/insights/37966934.pdf.

16 Jonathan Haidt, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions andBad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (London: Penguin, 2018), p. 209.

17 Robert Sapolsky, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst (London: Penguin, 2018), p. 208.

18 Tom Bennett and Jill Berry, Behaviour. In Carl Hendrick and Robin Macpherson (eds), What Does This Look Like in the Classroom? Bridging the Gap BetweenResearch and Practice, Kindle edn (Woodbridge: John Catt Educational, 2017), loc. 757.

12