4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BookRix

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

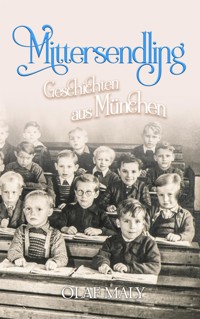

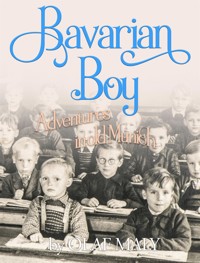

A childhood after the war: The leather pants are bought in a flea market behind the church, food is scarce and going to a movie is not even in the picture. But Hansi and his three best friends always have a solution up their sleeves. They find some excitement with no money at all. They explore ruins, secret tunnels, old buildings; and sneak into the public pool, drink secretly from the beer they have to buy and dream about careers as soccer stars.

Olaf Maly tells amusing, realistic short stories from old Munich. They arouse memories of a time when little boys could survive an adventure and didn’t have to fear anything. Except their mothers or a few girls. Although these stories play in Munich, the content is certainly universal.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Bavarian Boy

Adventures in old Munich

I want to say thank you to three people, without whom this book never would have become a reality. First, my years-long partner, Marita Stepe, who always reads all my books first and has a big influence on the tedious process of creation. Furthermore, my editor, Sue Hargis Spigel, who corrected all my mistakes in the English version and never told me how bad it was. Thank you, Sue. Last but not least, my cover creator Vivian Tan AiHua, who has always the best ideas.BookRix GmbH & Co. KG81371 MunichIntroduction

After reading some of the stories to a good friend, he suggested I should publish this book about a childhood in Munich also in English.

These adventures take place in the 1950s. Although the war had been over for a good 10 years, its scars remained wide open. Destruction and disorder could still be seen everywhere; the supply of day-to-day goods wasn’t always guaranteed; housing was scarce. Those with an apartment were among the lucky ones, but as the world goes, there were people who did not share that same luck. This is the environment in which four friends grow up together. One summer, they experience life just as they know it. For them there is no other way and they are happy. Their names are Hans Heinsberger (nickname Hansi), Franz Kerbel, Georg Friedel (Schorsch) and Anton Kranzlberger (Toni). Then there is a girl who is to play an important role in Hansi’s life. Although he doesn’t yet know it, it will be his first love, Maria.

I have kept the original German names for a purpose. I feel they are important for the environment in which these characters live. If I had changed them to English, this would have been a different story.

The people in these stories did exist. Perhaps not precisely as described, but very close.

Our housing complex

And here again was another hot summer. A summer that faded slowly and quietly from the spring. Just like that. All the leaves, which were a subtle green just days ago, changed to a more solid color without a big fanfare. The colorful blossoms detached themselves from the trees and covered the ground like a flower carpet on lush, green grass. We had to say goodbye to the pleasant evenings, when you could leave the window open overnight to cool down. And we had to accept the heat, wishing it would be winter again. Maybe not a real winter, but just a light breeze from the north. This year there was no low-pressure system, no cold spell. There was no storm named Gabi coming from the west, trailing over the Biscay before it came to us. Maybe just a waitress named Gabi, bringing cold beer under the shadow of an old chestnut tree, in which the small bubbles constantly and slowly rose to the top, like warm air to the blue Bavarian sky.

Everybody was sweating miserably. An obvious sign for the heat was that the schools closed early, which happened only above a certain temperature. And this temperature was reached. Who decided what this temperature was will be forever a mystery to us that only the Bavarian Government in its unlimited and inexhaustible wisdom would be able to solve. They recommended that we sit still, move only when absolutely necessary and drink as much as we could. Things they do every day, even if it’s not hot outside, and have a lot of experience in.

“Boy close the window. We don’t need all the bugs in here,” said my mother, who sat on the couch and patched up my pants, which were ripped again.

“If you don’t take better care of them, I will not be able to fix them anymore. And we can’t afford new ones either, as you know. Your uncle Karl promised to send us a pair, but this can take a while. You know your uncle. Everything takes forever.”

I was sitting close to her on the floor and listened patiently. My uncle lived in Nuremberg, a town north of us, maybe two hours on the train. We never went there. We had neither the desire nor the money to visit him. He was not a real brother to my mother, more of a half-brother.

“You know, Hansi, when there is the same mother and a different father, then your brother is just a half-brother. And for you, in this case, only half of an uncle.”

She didn’t want to talk about it, it was clear to see, when I asked her about that. But I couldn’t care less anyway if he was a full uncle or a half uncle; the main thing was that he was my uncle. We didn’t have any other male relatives, so I had to be happy to have one at all. As I talked with him about it, he said that I would be his only nephew, and he would not have to cut himself in half either. In this respect, I should absolutely consider him a full uncle.

Then there was my aunt Rosi. She was a full aunt, still living on the farm where my mother grew up. The big disadvantage of my aunt was that she always had to kiss me all the time. Then she permanently said what a good boy I was. But we didn’t want to be “good boys” in those days. We wanted to be feared and respected, but not “good boys,” for heaven’s sake. On top of this, she always took out a big handkerchief, spit into it a few times and washed my face with it. My half uncle didn’t do anything like that. Therefore, I liked him much more than my full aunt.

“I know how Uncle Karl is. He promised me a new soccer ball last Christmas and I’m still waiting for it.”

“What are you talking about? He gave you a new ball.”

“Mom, this rubber ball is not a real soccer ball. Everybody and his brother just laughed at me when I showed up with this one. It has all the colors one can think of and bounces like a small rubber balloon. This is something for girls, but not for future professional soccer players like us.”

“Professional soccer player?”

“Yes, we want to go to 1860 München. Only stupid Toni wants to go to Bayern München. But we have to start small, in the soccer club down there on the river.

Then, when they discover us because we are the best players on the field, you have to drive us to the club every time we train. Or a game. Only as long as I don't have my own driver's license, I mean."

The soccer club 1860 München has a long history in Munich. Since 1860. There were two groups in Munich. One group is fans of 1860 München, the other one is for Bayern München. We didn’t like Bayern München, since we were told that only the stinking rich played there. And we were not in that class. My friend, Toni Kranzelberger, was once with his father at a Bayern München game. Since that day, he always wanted to play there. But he was the only one in our group thinking like that. We considered it high treason.

My mother, who was laughing very hard and loud, looked up from her work. When she was able to speak, she said, “Boy, now you’ve really gone crazy. I will never drive you anywhere. We don’t even have a car. But at your age you still can have your dreams.”

Then she patted me softly on the head. I looked at her with determination.

“Mom, you will see, when you sit in the stadium and everybody is just yelling and screaming my name, because I shot another goal. Then you will not laugh at me anymore.”

“Aha. I thought you’re a goalie. I don’t understand very much about soccer, but I thought the man in the goal is supposed to prevent goals and not shoot them.”

“Mom, that was yesterday.”

The ignorance of my mother about soccer was legendary. During my whole childhood, and thereafter too for that matter, she never learned anything about the game. But regarding my career as a soccer player, she was right at that time. The small club down on the river had 11 teams. When my friends and I started to play for them, we had to join team number 11 and work our way up. Only the best were able to make it and be discovered by the big clubs. We never made it higher than team 8. My mother never had to drive me anywhere. But why she knew this already at that time is one of the big secrets that mothers carry around with them and never disclose.

“Georg meant that because I couldn’t hold any balls in the goal, I would be better as a striker. After all, I know how they shoot goals, since I cannot prevent them from doing so. Understand me, Mom. I have the experience to out-maneuver the goalie. Franz said I could be the second Uwe Seeler.”

Uwe Seeler was the best striker at the time and a big idol for all of us. Being compared to him did actually boost my self-confidence to reach new levels.

My mother dedicated herself to the pants again. My having played soccer a while ago was the reason why she was sitting there in the first place. She wagged her head slightly, as if she would doubt my ambitions.

“1860 München. In this case, my boy, we have to talk to your uncle and ask him for new soccer shoes.”

She did ask him, but it took a long time before he even came through and bought me some. They were used, old and too big for my feet. His argument was that they were already broken into, which means they already had field experience. As if this would be an advantage.

School was over two days earlier. This meant that we could sleep in, were free to roam the area, play soccer all day and just have a good time. We also would visit the other quarters close by to have some fun. They called it pollution, when we came, but this didn’t bother us. Just the contrary. We loved to be hated.

The area we lived in was called Mittersendling, which means we were in the middle of the three neighborhoods. Then there was Upper Sendling and Lower Sendling. The inhabitants of the upper and lower parts of the town considered themselves something better, the upper class. They told us we were the proletarians, the lower class. Only because we lived in big rental units. Behind the wall. Close to the coal and stone depot. They just thought they were better people.

There were also blocks of flats in those other quarters, but besides those, there were also single-family homes. We didn’t have that—houses, where only one family lived in. Without a neighbor right behind the paper-thin walls, as in our case, where everybody could hear anything that happened next door. Whether you liked it or not.

We didn’t know what it meant to be a proletarian until we asked our teacher, Mrs. Zwirbel, one day.

“Proletarians, my little kiddies” —she always called us this, even though we were not her little kiddies at that time— “are people in the working class. There are people who work, and there are people who sit in the office.”

“And don’t work,” added my best friend, Franz Kerbel, who sat right beside me, and laughed.

“No, Franz, they work too, but more with their head and mind. The proletarians work more with their hands.”

“And this is bad?” asked Georg Friedel, the one who asked the question in the first place.

His father was one who ran around in a suit all day. He certainly didn’t work with his hands. Georg meant that he worked for an Insurance Company. But he wasn’t sure, he could have also worked for the Secret Service. Or as an inspector at the Police Department. His father never talked about his work at home, so he really didn’t know crap. Since we thought the Secret Service would be the most interesting of the choices, we found a slot for him there.

“No, that is not a bad thing, Georg. Just different. Some people think it’s better to be in an office, that’s it. But now we’ll fetch our booklets and have a math test.”

It was always the same story. Whenever we had a good time, she had to ruin it with a stupid test. I think she just wanted us to know who really was in charge here. Or she ran out of answers.

Sometimes we just leisurely roamed the streets and looked for some entertainment that could lighten up our day. This was in most cases kids in expensive clothes or on overpriced bicycles. When they saw us, they just took off and disappeared. Only when we were outnumbered, then we had a small problem. Then we were the kids running away. If that didn’t work, we sometimes could end up with some bruises. But in the end, it all balanced out somehow.

Many of the small houses in the area were empty. This was how it was after the war. The owners were either dead or gone. Most of these dwellings didn’t have windows or doors anymore, since owners of the ones that were inhabited took what they needed to fix up their own abodes. One could see this, since the windows and doors didn’t really fit in the renovated homes. When a house was empty, we just went in it to explore. When there was a couch or anything else where we could sink in, we sat there and had the feeling of being unbelievably rich. Then we called our servant for a cold lemonade. Nobody came, obviously, but this didn’t matter. We just loved to be in a house all by ourselves. We were delighted to experience how some people lived. And we dreamed that one day, we would be one of them.

Sometimes there was a small pond in the garden, grown over with weeds, dark and mysterious. Then we planned to excavate the treasure, which was certainly buried somewhere there. We never found anything. Or there was a swimming pool, which was filled in with all kinds of rubble.

“Having our own pool would be nice,” was the comment from Franz, “then we would not have to go the stupid public pool all the time.”

This is how we spent some days, until somebody came and chased us away again. Then our dreams were gone for a while and reality caught up with us once more.

There was also a bookstore in this area behind the wall. None of my closest friends were ever interested in books, except me. They were my escape to an unknown world, which I thought was much more glorious than the one I lived in. A world where everything was better: everybody had enough money to buy what they needed. Nobody was ever hungry. Everybody had enough to eat, every day. Nobody was ever freezing just because it was cold outside. And nobody had lice in their hair which feasted on us and ate us alive. You never read about this in these books. That's why I liked those books. I dived into a world in which I had wished to live.

The bookstore smelled wonderful. At that time, I didn’t know what it was, what made me wish to breathe in this aromatic smell and take it home with me, to have it all the time. Now I know. It was the printer’s ink, the paper and the glue. The unmistakable and mysterious smell of books. When one opened the door and the sun was shining right, then you could see the fine dust coming out of the pages and floating silently in the air. I was always afraid that these were all the words which escaped and couldn’t be read anymore. They would be lost forever, annihilated before someone could see them, for me a dreadful thought. I was just fascinated by the fact that one could tell so many exciting stories just by placing words next to each other.

When one entered the store, there was a small table to the right, a little bit higher than a normal desk. On it was an old cash register. This was the place where you paid for what you took home. On the left side was a large, white bookcase full of all the wonders. Straight ahead was a dark blue couch, where one could sit down and read. In front of it was a small shelf with magazines.

Mrs. Bleicher, who owned the store, was a slim, tall and elegant woman. I had the feeling that she had already read all the books that were there. Maybe even more. Somehow you could see this. I envied her.

She had gray hair, which was bound on the back of her small head with a black ribbon as a queue. She was always dressed in a long gray dress, which almost touched the floor. Over it, she had a light blue sweater. Only when it was hot could you see her without it. She sat behind the desk and read a book or magazine, which was open in front of her. When somebody came in the store, she just looked over her small reading glasses and greeted them. She knew her customers, almost every one of them. It was a small world, this bookstore. I was not a customer, just a little boy who didn’t want to do anything else but read. Nevertheless, she always greeted me by my name when I entered.

“Good morning, Hansi, you are here again. You can sit down over there on the couch. I got a new book in, which you should read. It’s a story of a ship which runs against a cliff. Most of the sailors drown, except a few, who are saved by the natives. But this is all I’ll tell you; otherwise, all the suspense is gone. Just one more thing.”

She put on a sad face:

“It doesn’t end well.”

Then she came out of her corner, went to the shelf, looked for the book and gave it to me. I went to the couch and she back to her desk. I sat down and enjoyed the total silence, which floated above me and sank into the fascinating world of ships and sea and storm. It was as if I weren’t there. Not for Mrs. Bleicher or anybody else, for that matter. Or even for myself.

Mrs. Bleicher knew that I couldn’t afford to buy a book. With my much-too-big formerly white shirt, which wasn’t so white anymore, the old sandals and the short leather pants, which hung on me like they didn’t belong to me, she knew that I came from the public housing complex behind the wall. And she also knew, when we met the first time, that I was fascinated by books, as I was standing there in front of the store and looking in amazement. I must have been staring in the window for a long time. She came out of her store, took me by the hand and showed me to the blue couch.

“Sit down, over there,” she said. “But before you do that, you have to tell me your name.”

“Hansi is my name. And I would like to read the book with the Indian on it that is in the window. But I don’t have any money and my mother…”

She interrupted me and said: “You see, Hansi, I thought so, that you want to read that book. And I also see that you don’t have the money to pay for it. But that doesn’t matter.”

She went to the shelf, took the book out and gave it to me. I ran to the couch, sat down and didn’t stop reading until she said she had to close the store. The title was The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper. That was my first book ever. I will never forget it. I couldn’t stop. Mrs. Bleicher came over to the couch and tore me out of my world.

“You can come tomorrow, if you want to, and continue reading.”

I had to stop, and I went home and couldn’t wait to come back. I not only came back the next day. I was in that store as much as I could be, and we became very good friends, Mrs. Bleicher and me.

The direction opposite the bookstore, when we left the housing complex, was an empty street, with a storage area for stones, pebbles and coal. The street was just cleared from all the rubble and still looked like a large lesion right through the heart of town. No house, or what was left of it, was higher than a few meters. Why it was this way, we didn’t know. They just told us not to go in that direction.

“Keep right” was what everybody said. Stay out of the area to the left. Go to the right. In this direction was life, adventure and excitement. This was our small world that we lived in, if only in our dreams and heads sometimes. And in this wonderful world of books.

The lost soccer baall

Where we lived there, as I already said, was a wall surrounding our complex. This wall went around the whole site and enclosed most of the public housing complex. It wasn’t very high, but still a wall, separating us from the little houses. For us kids, the wall seemed to be very high anyway, since we were not very tall. Much too high. One could not look over it, even standing on one’s toes. Franz Kerber, my best friend at the time, was at least a head taller than I was, since he had had to run a lap of honor at the school, which means he had to repeat the last class. In reality, he should have been one class higher than I was. When somebody asked him about that, he claimed that he liked our teacher, Mrs. Zwirbel, much more than the other teacher, Mr. Zwick, whom he just hated. He was hoping that after the additional year with Mrs. Zwirbel, Mr. Zwick would be gone. This would solve the problem for him.

“I hope he will retire soon, Hansi. I can just repeat this class one more time and then it’s over.”

This was the reason why he was one head taller than I was. And because of this, he was standing with his back against the wall, folding the fingers of his hands into each other to form a surface I could stand on. I put my foot on this step to hoist myself up on the wall, to be able to look over it. First, he was holding his hands very low and started to pull me up.

“Boy, you are heavy,” he complained loudly. “Help me a little bit and grip the wall to pull yourself up.”

I did what I could, without any big success.

“Do you see something?” he asked, when I finally got hold of the last row of bricks on top of the wall and was able to somehow hold steady.

“Nothing special. Just a few houses and some gardens. Flowers, trees. Otherwise, nothing exciting.”

“I know that there are houses, you simpleton. I mean the ball. Do you see our ball? It cannot be that you don’t see the ball. Just take a look. Don’t tell me you don’t see anything.”

“If you don’t believe me, look for yourself.”

“And how, exactly, would I do this, standing here and holding you up?”

He certainly was right with that scenario. I took another hard look and let my eyes wonder around the area.

A few minutes earlier, we had played soccer. The plan was that Georg Friedel, another member of our group, was supposed to pass the ball to my friend Franz. I was the goalie, standing in perfect position between the posts and waiting for the ball to come. My other friend, Anton Kranzlberger, was standing right in front of me, playing the defender. He never would have had a chance to get the ball, since he never did. I was the last resort. Instead of passing the ball, Georg just shot it to the goal, since he wanted to prove that he was a good striker, although we told him more than a hundred times that he was a dull loser and wouldn’t hit a barn door from 2 meters.

He yelled, “I can make it,” and this is how our ball ended up over and behind the wall. The ball was gone. This was the only leather ball we had, and it disappeared. We had another rubber ball, but this one didn’t count. This was a ball for girls, and not for soccer hopefuls.

“And now, you idiot?” Franz yelled angrily. “What are we going to do now?”

Screaming swear words, which I really shouldn’t repeat here, he ran after Georg, since he wanted to kick him in his lower back. Or ass, for that matter. He failed miserably and swung his leg into empty space, which made him perform a half loop around himself, to which we applauded loudly and enthusiastically. This made him even angrier and he yelled after Georg: “You will regret this the rest of your life, you stupid, brain-dead, village idiot.”

Anyway, after a few minutes of fruitless discussion and after we calmed down a bit, we decided to take a look at where our ball could be. And this is how I ended up standing on the hands of my friend Franz to look over the wall.

“I see it, I see it,” I shouted in excitement. “It’s in the flower bed. Oh my gosh, the flowers are toast. You can’t even put them in a vase anymore. They will not be very happy, seeing this.”

At that moment Willi Steiger, the son, came out of the house. He went to school with us. We knew him. He knew us. He thought we were lower class, antisocial elements, since he lived in a house and we in the public housing complex behind the wall. He was one of them, calling us proletarians. Besides that, he always wore a bow tie and a checkered shirt to school. During winter time, he even had a jacket or coat, which we didn’t have. And his pants were made of fabric, not rough leather, which constantly rubbed on our legs, until there was no skin anymore. He also had real shoes, made from leather. We had a pair too, but were only allowed to wear them on Sundays, and then they pinched so hard and hurt so badly that we took them off anyway. What we had were cheap sandals, which we could only use as goal markers. Had we used them to play soccer, the soles would have gone in no time and we would have been in big trouble, since we had to fix them again, which we couldn’t afford. Then the only issue my mother would talk about for days was how expensive this was—again.

When we met Willi at school (he was one class above us), we called and asked him to use his bow tie as a prop, like a helicopter.

“Why don’t you turn your stupid prop on and take off, Willi,” we yelled and half of the school started laughing. He couldn’t care less. He just turned his tie and looked at us contemptibly.

“Willi is in the garden now,” I whispered to Franz, who seemed to get redder and redder in the face.

“Tell that prude to throw over the ball. I can’t hold you much longer.”

“Willi,” I yelled at him, “shoot the ball over to us, which is in the flower bed over there.”

He looked at me and then turned around to search for the ball. When he saw it, he turned around to me and said, with a sneer on his lips: “Why don’t you fly over here and pick it up yourself, you stupid proletarian?”

I didn’t know yet what a proletarian was then, but knowing Willi, it couldn’t be anything good. That was for sure. I asked Franz what that could mean, but he didn’t know either. So we concluded that it was not good. Then I asked Franz what we should do next.

“Tell him,” and now it came very laboriously out of his mouth, “that I personally will smack his ugly face to pieces if he doesn’t shoot the ball over here immediately. Tomorrow in school he will feel the consequences. He will not forget this the rest of his life, this low-life bastard. Even his mother won’t recognize him anymore when he comes home. I have already waited too long for the moment to show him who has the say here in the area. Tell him that.”

I relayed the message to him as well as I could, always making sure that it came from Franz and not from me. He would take him on and beat him up, not me. I thought it would be important to mention this. Willi just stood there with a stupid grin on his face and didn’t say anything.

After a while, he said: “You can pick up your stupid ball yourselves, you useless proletarians. I will not give it to you.”

Now he used that word again. If he used it twice, I thought, it really must be bad. Idiot, pig head, loser, monkey, all those terms (and much worse) were normal for us and we could live with them. We even called each other these names. But proletarian was new.

“He always calls us proletarians. I think this has something to do with people who work and the ones who don’t work. The ones who waste away the days in the office.”

“I don’t care what he calls us. I will smack him in his stupid mouth tomorrow so that he knows how proletarians can hit.”