Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

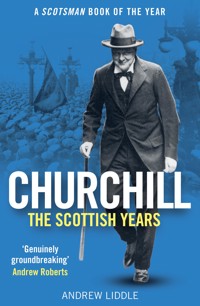

This is the true story of Winston Churchill and Scotland. In the popular imagination, Winston Churchill is the bulldog of 1940 – uncompromising and Conservative. But in 1922 he was the reforming, progressive Liberal MP for Dundee who, after five successive election wins and a majority of 15,000, could confidently claim to have a seat for life. But one man had other ideas. This is the story of how god-fearing teetotaller Edwin Scrymgeour fought and won an election against Britain's most famous politician. Andrew Liddle vividly brings to life an extraordinary rivalry as it unfolded over fifteen years, and also explores for the first time Churchill's controversial Scottish legacy, including his attitude to devolution. 'Rich and well-written . . . a vital insight' – The Scotsman 'A fascinating story' – Times Radio 'A brilliant book' – Andrew Adonis

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 502

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2022 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Andrew B.T. Liddle, 2022

ISBN 978-1-78027-789-9EBOOK ISBN 978-1-78885-535-8

The right of Andrew Liddle to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by

him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available on request from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

Preface

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Facing Oblivion

1 ‘What’s the Use of a W.C. without a Seat?’

2 The Road to Scotland

3 ‘I Chose Dundee’

4 A Seat for Life?

5 Vote as You Pray

6 Enter, Clementine

7 ‘Not at Home’

8 Our Man in Dundee

9 The Peers versus the People

10 The Strike before Christmas

11 Home Rule

12 An Activist Victorious

13 The Policeman, the Pilot and the Prohibitionist

14 War

15 On the Front Line

16 The Home Front

17 ‘Shells versus Booze’

18 Winning the Peace

19 Revolution

20 Resolution

21 Clementine’s Campaign

22 The Final Round

23 Last Orders

24 Closing Time

25 Hangover

Afterword

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

Picture Section

Preface

Scotland had a profound impact on Churchill – practically, politically and personally. Practically, it provided him with a constituency for almost 15 years, five election victories and a platform from which he could launch his cabinet career. Crucially, the voters of Dundee backed Churchill during some of his most difficult moments. Without victory in Dundee in 1908, Churchill’s political career would have been in serious jeopardy. Equally when voters in Dundee chose to endorse Churchill in 1917, they helped cast off the aspersion that he was a political liability in the wake of the failure of the Allied Dardanelles campaign in 1915. These were two crucial endorsements, but the strength of his support was clearly apparent at every election he contested in Dundee until 1922. Even then, as the city voted him out, he received more than 20,000 votes.

Politically, and perhaps most importantly, serving in Scotland changed Churchill’s Liberal perspective from one concerned solely with economics to one that also embraced progressive social reform. Churchill had left the Conservative Party for the Liberal Party in 1904 because of his belief in free trade, and his alignment with the Liberal Party until 1908 was fundamentally due to economic policy. It was support for free trade that won Churchill the Manchester North West constituency in 1906, and it was international affairs that dominated his ministerial career between then and 1908. It was only once he became MP for Dundee – and came to more fully understand poverty, slums and ill health – that his political priorities evolved and he became a champion of social, as well as economic, progress.

Personally, and most prosaically, Scotland also had a profound social and private influence on Churchill’s life. His wife, Clementine, hailed from Angus, and Churchill retained many lifelong friends from Dundee and wider Scotland. His holidays in places such as Aberdeenshire and East Lothian provided much-needed respite from the trials and tribulations of high office. Most importantly, it was a Scottish regiment that helped Churchill recover when, in 1916, his career was at its lowest ebb to date. With his mental health under strain, Churchill took command of the 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers, and it was in the trenches, among the Scottish accents and Glengarries, that he began his recovery.

Despite the significance of Scotland to Churchill, it is a subject that is curiously missing from the vast mass of work on his life. Only one full-length book on the topic, published more than 30 years ago, has ever been attempted. Even then, the focus of that volume is primarily on telling the chronological narrative of Churchill’s life between 1908 and 1922, rather than also exploring his relationship with Scotland in depth. Equally, given the vast scope of Churchill’s life and achievements, more recent biographers understandably pay little attention to his time as an MP in Scotland, which is generally referred to in passing. While several useful academic articles on Churchill’s time in Dundee do exist, they tend to focus on placing Churchill’s defeat in 1922 in the context of broader political or socio-economic trends. The International Churchill Society, which seeks to promote the life and work of its namesake, dedicated a 2020 issue of its quarterly magazine Finest Hour to the topic of Churchill and Scotland, which received considerable press interest. But a void undoubtedly still remains on this important aspect of Churchill’s political and social life.

There are several explanations for this absence. Even the most persuasive writer could hardly claim Churchill’s political life from 1908 to 1922 – while not without its considerable achievements – was more significant than the role he played in British and world history in the 1940s. It is therefore completely natural that this is where the interests of the public and most historians and writers lie. At the same time, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement and a broader awareness of racial injustice has sparked a greater interest in Churchill’s views on race and empire, the study of which tends largely to ignore his earlier life and period in the Liberal Party.

In this void, misinterpretations, misunderstandings and even outright falsehoods about Churchill’s association with Scotland have gained increasing traction among historians and the public. Many of Churchill’s main biographers give the impression that he had a difficult relationship with Dundee and Scotland more widely. He is often described as a ‘carpetbagger’ with little interest in the affairs of the city, while many also assume Churchill opposed devolution or was dismissive of Scottish national identity and culture. Much of this is based solely on Churchill’s defeat in what he thought was a ‘life seat’ and that, in 1943, he tersely rejected an offer of the Freedom of the City of Dundee. Churchill’s amusing outbursts about unsophisticated Dundee hospitality add to this impression, despite making up a tiny proportion of his private writing on the city. In a similar vein, it is taken as a given that Churchill loathed his arch-adversary, the prohibitionist Edwin Scrymgeour, because the pair were the political and personal antithesis of each other. Churchill’s relationship with Edmund Dene (E.D.) Morel, the Labour candidate in 1922, is similarly dismissed because of the latter’s socialism and pacificism.

As well as such assumptions, genuine falsehoods abound, most infamously that Churchill ordered tanks into Glasgow’s George Square to suppress strikers in 1919. This myth is now so pervasive in Scottish society that it has been put on school syllabuses and been included as a correct answer on exam marking keys. Some of this is a result of contemporary political debates in Scotland overshadowing Churchill’s life. The legacy of the man voted the Greatest Briton by BBC viewers in 2002 is often held up by both pro- and anti-Scottish independence activists to support one point of view or another. Scotland’s rejection of Churchill is, for example, often cited as Scotland rejecting Britishness, a metaphor that is strengthened by the fact that Dundee had the strongest pro-independence vote in the 2014 independence referendum. Scotland is far from unique in this phenomenon. For example, Churchill’s legacy was invoked by both Leave and Remain campaigners in the 2016 EU referendum. Nevertheless, there is clearly an absence of understanding about Churchill in Scotland that needs to be addressed.

Cheers, Mr Churchill! is primarily a narrative history of Churchill’s time in Scotland and his political battles with Scrymgeour and Morel. It tells the compelling story of how and why Churchill won elections in Dundee, his rhetorical clashes with Scrymgeour, his real clashes on the Western Front and his eventual defeat at the hands of a teetotaller. It explains how Scrymgeour – and, indeed, Morel – rose from almost nothing to defeat one of the most prominent politicians of the era. And it highlights how women – Churchill’s wife Clementine, but also suffragettes – played an outsized role in his victories and defeat in Dundee. The aim has been to make the account open and engaging, and so that – as much as possible without excessive divergence – readers need little background knowledge of the period or Scotland in order to understand and enjoy it.

But this book also seeks to challenge the key assumptions made about Churchill’s time in Scotland, as well as his relationship with Dundee. This has been possible by returning to and re-evaluating the wide-ranging source material from the time. Not only did Churchill himself leave extensive correspondence, notes and reflections on the period from 1908 to 1922, but those of his staff and parliamentary colleagues are equally voluminous and accessible. Both Scrymgeour and Morel also left substantial personal papers, many of which pertain to Churchill’s time in Scotland and their political battles with him in Dundee. Newspaper reports, as well as photographs and even early film, add significant metaphorical if not physical colour and help develop understanding of the period even further.

By revisiting this material, a more nuanced picture of Churchill in Scotland emerges. While he could hardly be described as a good constituency MP – apart from anything else, such a term, pre-welfare state, is anachronistic – Churchill was not dismissive of Dundee or its constituents. Much of the progressive legislation he introduced, particularly before the First World War, helped improve the lives of his constituents, including raising wages in Dundee’s dominant jute industry. He also genuinely cared about issues in the city and was responsive to even minor requests from individuals, such as helping secure artillery pieces for the city’s Boys’ Brigade. If he visited the city less frequently than his critics would have liked, this was common practice among his contemporaries – including his fellow Dundee Labour MP, Alexander Wilkie, and his successor, Morel – who felt they were sent to represent their constituents in Westminster, not vice versa.

Cheers, Mr Churchill! also reveals for the first time the close relationship that existed between Churchill and his Prohibitionist adversary, Scrymgeour. While Churchill undoubtedly had a trying relationship with Scrymgeour, he retained a begrudging respect for his keenest adversary. This respect extended to hosting Scrymgeour as his guest at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, with Churchill even lending him his car and driver. Likewise, this book also sheds light on the early relationship between Churchill and Morel. Contrary to popular belief, the pair were on good terms in the early 1900s, with Churchill being the first MP to contribute to Morel’s West African Mail, a journal that helped expose the horrors taking place in the Belgian Congo. Even Churchill’s rejection of the Freedom of the City of Dundee is more complex than first assumed: Churchill was in fact acting on the advice of his Scottish Secretary, the Labour MP and former Dundee representative Tom Johnston, who had urged him against accepting because of divisions among city councillors over the offer.

Cheers, Mr Churchill! also fully explores for the first time Churchill’s attitude to Scottish nationhood and political autonomy. It reveals how he advocated for a system of devolution as early as 1901 and continued to be open to a form of Home Rule for Scotland throughout his time as an MP in Dundee. In a speech in 1913, he described a federal United Kingdom as inevitable. Much of this thinking was brought on by the question of Irish Home Rule, but Churchill – with both cruel logic and sincerely held belief – applied the same questions and principles to Scotland as well.

None of this is an attempt to recast Churchill as a Scottish hero, or to suggest that Dundonians were wrong to reject him in 1922. Churchill made many mistakes during his time as an MP for Dundee, both on a local and national level, which are deservedly highlighted in this account. Rather, Cheers, Mr Churchill! is an attempt to better understand what Churchill actually thought of Scotland, and what Scotland thought of him, particularly during the period he was an MP in Dundee. A century on from Churchill’s defeat, it is more important than ever to understand his place in Scottish history.

Andrew Liddle

Edinburgh

August 2022

Author’s Note

For currency conversions, I have used the National Archive’s Currency Converter: 1270–2017 to give an indication of the modern purchasing power of the sums described. The converter offers input on a five-year basis (i.e., 1900, 1905, 1910, 1915 and 1920) and, where the dates are not exact, I have rounded up to the nearest year. If multiple figures are quoted in succession, a conversion of only the first figure is included.

All individuals are referred to initially by their full name, and from then onwards by their surname. The exception to this is members of Churchill, Asquith and Scrymgeour’s family who, to avoid confusion, are referred to initially by their full name, but from then onwards by their first name.

The book follows a chronological timeline as much as possible. However, in some of the more thematic chapters it has been necessary, for both readability and argument, to include material from elsewhere in the timeline. Where this has occurred, it has been clearly marked. As a guideline to help readers, each chapter also contains an approximate date range for the events being discussed.

I have included references as endnotes and a select bibliography of materials I have consulted. Any and all mistakes, however, remain my own.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the staff at the Churchill Archive, Dundee Local History Centre, LSE Archive and British Newspaper Archive for all their help and assistance with the research for this project. I am also grateful to Murray Thomson for his early help and advice, as well as to David Powell, the D.C. Thomson Archive manager, for his assistance.

This project never would have happened without the support and enthusiasm of Hugh Andrew at Birlinn. He saw its potential from the start and has fought for it ever since, providing crucial feedback along the way. I am also extremely grateful to Andrew Simmons for his insightful editorial suggestions and to all the other staff at Birlinn who have helped produce this book. Craig Hillsley, in particular, has my enduring thanks for his judicious and thoughtful editing of the manuscript.

The study of Churchill in Scotland is far from my exclusive remit and many others have undertaken extremely valuable and important research on the topic. I am particularly grateful to Gordon Barclay, whose work on Churchill and the events of George Square in 1919 is ground-breaking and invaluable, and Alastair Stewart, who has almost single-handedly fought to raise the profile of Churchill and his Scottish links. He has been generous with his time and knowledge from the off, and I am extremely grateful for his help and support. I am also indebted to the vast field of historians and writers who have contributed to the wider study of not just Churchill – but also Scrymgeour, Morel, Dundee and the period as a whole – whose work has been an influence on this book. It is obviously not possible to thank them all individually, but I have included a selection of the materials consulted in the bibliography section.

A number of close friends have read early drafts of the manuscript and provided helpful feedback. My thanks, in particular, to Gordon McKee, David Torrance and Christopher Smith for their insightful and useful comments. Tony Halmos has been a consistent and extremely generous supporter of my literary efforts, for which I am enormously grateful. Freddie Burgess, Hatty Hubbard and The Disco also deserve thanks for, at one point, lugging my collection of books across the country.

My parents, Caroline and Roger, have been an enduring support not just with this project but throughout the last 33 years of my life. Their encouragement and advice have been key, and I am particularly grateful to Roger, who kindly lent me much of the secondary material for this book from his own library. Thank you both so much, for this and everything.

Shonagh has had to live with ups and downs of Cheers, Mr Churchill! more than anyone. It has accompanied us throughout our engagement, new house, marriage and honeymoon. At one point, I even disappeared for four whole weeks to finish the first draft. Not only has she never complained, but she has been a constant source of inspiration, support, encouragement and love. I could not do this – or anything worthwhile – without you.

This book, however, is dedicated to my grandfather, George Thomson. George was one of Churchill’s successors as MP for Dundee and provided the introduction, more than 30 years ago, to the only other dedicated book on this subject. But, much more than that, he inspired me to love history and politics, and his influence is one of the main reasons I am able to write this book today. I hope he would have enjoyed it.

Introduction

Facing Oblivion

1922

Winston Churchill sat alone in a corridor in Dundee’s newly completed Caird Hall on 16 November 1922. Despite being dressed in a thick wool three-piece suit, he occasionally shivered. It was winter in Scotland, and cold. Earlier, he had briefly chatted to the bemedalled porter who had carried his solitary seat into the corridor. Churchill had inquired into his war record, but otherwise had spoken to no one for more than an hour. He was pensive and valued the peace. In his right hand he held a large cigar, which he puffed at reflectively, indifferent to the ash falling on the recently polished marble floor. He looked and felt tired. His usually cherubic face was gaunt and emaciated, his suit hung off his body. Not only had it been a tense and trying election campaign, but the wound from his recent surgery was still fresh. If you were to run a hand along his waistcoat, you would feel the raised stitching along the five-inch incision across his abdomen.

Occasionally, Churchill stood up and strode determinedly towards the open window at the end of the corridor, from where he could see the Tay River, Dundee’s most dramatic feature, shimmering in the crisp winter sun. Commercial ships dotted the estuary, travelling to and from the city’s docks and out into the stormy North Sea. Further in the distance was the Tay Rail Bridge, which had been one of Churchill’s main conduits to the city over the last 15 years. But his vista was dominated by the vast monuments to the city’s main industry – jute. Smoking chimney stacks towered over the city’s sandstone tenements, factories sat on street corners, vast warehouses overlooked neighbourhoods. This titanic array of industry was connected by arteries of cobbled streets where carters, manning horse and wagons, moved raw jute or finished fabrics around the city and down to the docks for export.

It was a scene Churchill knew well, but today it was of little interest. Instead, he looked immediately down on the city’s Shore Terrace, where a vast crowd of voters had gathered. What could he divine from the thousands of dirty, hungry, upturned faces? What did they have in store for him this time? They certainly shared his anxiety. Excited murmurs intermittently rippled through the crowd. Predictions and anecdotes from polling day were exchanged. Jokes were made, breaking the tension, and nervous laughter could be heard, only to quickly die down again. From time to time a shout went out in support of one candidate or another and, as Churchill strained to look more closely, he could see the faces of his supporters, many of whom had backed him at every election since 1908. Had things really changed so much since then, he wondered.

Dundee had saved Churchill’s political career. When he was invited to stand as the Liberal Party candidate in the city, his future was in the balance. Churchill had just been defeated in the Manchester North West by-election and his first cabinet role, as President of the Board of Trade, was under threat. If he had been defeated in Dundee, his career – not to mention the Liberal government itself – would have been in jeopardy. One by-election defeat looks like bad luck, but two in a row looks like incompetence. Instead, Dundee resoundingly returned Churchill as their MP, and continued to do so over the next four elections. He won the seat at both 1910 general elections. In 1917 – even after Churchill’s prominent role in the Dardanelles debacle – Dundee kept its faith in him, re-electing him and endorsing his return to the cabinet as Minister of Munitions. In the 1918 general election, he received one of the biggest majorities in the country. Far from hubris, Churchill’s prediction to his mother that Dundee was a ‘life seat’ and ‘cheap and easy beyond all experience’ was so far proving notably accurate.

This was largely because, despite these private displays of confidence, he did not take the Dundee electorate for granted. After his election in 1908, he threw himself into delivering the progressive, reforming agenda his constituents demanded. He and Lloyd George soon established a reputation among Conservatives as the ‘terrible twins’ of the Liberal Party, introducing measures such as old-age pensions, minimum wages and labour exchanges, which helped form the foundations of the welfare state. Further afield, he won the support of his immigrant Irish constituents by being an active supporter of Home Rule – willingly extending the concept to Scotland, as well.

But as Churchill stood at the window in the Caird Hall staring down into the crowds on 16 November 1922, he knew that despite these efforts, all was not well. Many of the personalities who had helped him in Dundee were now gone. His erstwhile running mate, the moderate Labour MP Alexander Wilkie, had stood down, deciding the 1918 general election would be his last. Wilkie had sat alongside Churchill in the two-member Dundee seat for his entire period representing the constituency, and they had developed an excellent working relationship. His absence was a bitter blow. So, too, was the loss of Sir George Ritchie, the chairman of the Dundee Liberal Association. Ritchie had been influential in securing the Dundee nomination for Churchill, and it was Ritchie’s wise advice and shrewd political counsel that he was most grateful for – and which, today of all days, he missed the most. Worse still, Churchill had also made prominent enemies. David Coupar Thomson, mogul of the eponymous Dundee media empire, had always distrusted Churchill, but in recent months their relationship had soured, descending into public acrimony. Churchill had accused Thomson of bias against him. Thomson, in turn, had accused Churchill of trying to bribe him, with the entire tit for tat exchange published prominently in his newspapers.

Then there were his two main political opponents, who Churchill knew all too well. As far back as 1903, he had supported the Labour candidate, Edmund Dene Morel, in his early work to expose the horrors of King Leopold II’s rule in the Congo. But since then, the pair’s paths had significantly diverged. Morel had been a prominent opponent of the First World War, even being imprisoned because of his pacificist campaigning. That experience, which had drawn him towards the Labour Party and eventually the constituency of Dundee, held little truck with Churchill.

But it was his second opponent, Edwin ‘Neddy’ Scrymgeour, who was his most implacable and remarkable foe. Scrymgeour had challenged Churchill at every election he had ever fought in Dundee. In his first, in 1908, Scrymgeour barely secured more than 600 votes and lost his deposit. But he did not give up, and each time he fought a campaign, his level of support slowly rose. By the 1922 general election, Scrymgeour hoped he might finally be on the cusp of the great victory that had so far eluded him. His commitment to defeating Churchill is in itself notable – few other politicians could weather constant defeat and still keep going. But it is all the more remarkable because of Scrymgeour’s unique ideological platform. He was leader of the Scottish Prohibition Party and viewed it as his divine mission to ban the sale and consumption of alcohol, which he argued was the root of all evil. It would be hard to find a political candidate that Churchill, at face value, had less in common with.

Yet, over the course of their 15-year rivalry, Churchill had developed a begrudging respect for his erstwhile political opponent. He admired Scrymgeour’s resilience in the face of adversity, and his determination to succeed despite seemingly insurmountable odds. While he disagreed with him on practically every issue, he also respected his authenticity and sincerely held beliefs. The two were never friends, but Churchill did not hold him in contempt. In 1919, Churchill even helped Scrymgeour with a journalistic assignment at the Paris Peace Conference. Yet Churchill still found it difficult to view Scrymgeour as a credible political threat going into the 1922 general election.

The campaign itself had been difficult to read. Apart from anything else, Churchill had only been able to get to the city four days before polling day as a result of his emergency surgery. In his absence, his wife, Clementine – whose family came from nearby Kirriemuir in Angus – had ably campaigned in his stead, but it remained unclear how well Churchill’s support was holding up. Recent events – particularly the Russian Revolution and the Anglo-Irish War – had certainly put his electoral base under strain. Many workers in Dundee resented Churchill’s bellicose attitude to the Bolsheviks, while his standing with Irish voters had been damaged by his support for the Black-and-Tan paramilitaries in Ireland. His record as a reforming cabinet minister, Irish conciliator and Home Rule supporter was being increasingly forgotten by voters more concerned with recent events. As the votes were counted in the Caird Hall that day, Churchill’s future in Dundee once again hung in the balance.

After a few minutes looking down at the crowd, Churchill turned away from the window to walk back to his solitary seat. As his footsteps echoed across the marble, a returning officer entered the corridor carrying a single sheet of paper. Churchill had been to enough election counts to know it contained the result of the vote. Without hesitating, he took the piece of paper firmly in his hand and looked down to learn his fate.

Chapter 1

‘What’s the Use of a W.C. without a Seat?’

1908

On 8 April 1908, Churchill was formally invited to join the cabinet for the very first time. The Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, offered him the presidency of the Board of Trade – roughly akin to Secretary of State for International Trade today – which Churchill readily accepted. At 33 years old, he would be the youngest member of the cabinet since Spencer Cavendish, the 8th Duke of Devonshire, in 1866. He would be one of only a handful of political prodigies – such as Pitt, Palmerston and Peel – to secure such a role in their early thirties. But the appointment was not unexpected. Churchill had already performed admirably – if not quietly – as Under-Secretary of State in the Colonial Office, a junior ministerial position, and, as a rising star in the Liberal Party, he was ready for promotion. But there was one significant problem. In order to be promoted to the cabinet for the first time, Churchill had to submit to a by-election in his constituency of Manchester North West. If he was defeated, it could throw his entire political future into jeopardy.

Churchill had first won his constituency of Manchester North West two years earlier, at the general election of 1906. It was a significant step on what had already been a remarkable political journey from Conservative whippersnapper to Liberal leading light. Yet, little about Churchill’s life or career to date had been conventional.

Born on 30 November 1874, at Blenheim Palace – his family seat – he was the son of Lord Randolph Churchill and his wife, Jennie. Lord Randolph, the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, had just embarked on his career in politics when Churchill was born. As Conservative MP for Woodstock, Lord Randolph quickly made a name for himself as an impressive parliamentary performer, but he also established a reputation as a political opportunist with a penchant for self-promotion. He was particularly good at fashioning memorable and cutting quips, the most famous of which came in relation to his support for Ulster unionism: ‘Ulster will fight, and Ulster will be right.’ Lord Randolph’s career culminated in his brief appointment as Chancellor of the Exchequer, at the age of 37 in 1886, in Lord Salisbury’s second administration. After just five months in the role, Lord Randolph resigned in a dispute with his cabinet colleagues over his plans for the budget. The move was probably meant to be a feint, but Lord Salisbury – fed up with Lord Randolph’s erratic behaviour – readily accepted it, effectively ending his political career. He died just eight years later, in 1895 – possibly as a result of a syphilis infection, which may also have contributed to his fitful behaviour. Churchill was barely 20 years old, and the death of his unfulfilled and embittered father affected him deeply.

Churchill enjoyed marginally closer relations with his mother, Jennie. The daughter of a wealthy New York businessman, Leonard Jerome, Jennie had married Lord Randolph in April 1874. The marriage, however, was not a happy one and both partners engaged in extramarital affairs, leading to questions over the paternity of Churchill’s younger brother, Jack, born in 1880. Churchill retained a great admiration for Jennie, however, and regularly wrote to her from boarding school and, later, when serving in the military overseas.

Churchill enjoyed a fairly typical education, despite the turbulent public and domestic life of his parents. He attended Harrow, a public school in the north-west suburbs of London, but did not excel academically and, rather than attend university, applied to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, gaining entry on his third attempt in 1893. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars – a cavalry regiment – he was initially posted to India. But, eager for action, he used his mother’s influence in high society to get posted on several military campaigns, including in Cuba, modern-day Afghanistan and Sudan. These campaigns were extremely dangerous, and Churchill often saw combat. But he also combined his role as a soldier with that of a journalist, writing lucid accounts of the wars he witnessed. Newspapers were soon paying him for articles, and he also published full-length books recounting his experiences, such as The River War, a best-selling account of the war against the Dervishes in modern-day Sudan. These books and articles marked Churchill’s first foray into professional writing, which proved a lucrative hinterland for him for the rest of his life.

Churchill’s most famous military escapade came in modern-day South Africa when he was nominally working as a foreign correspondent covering the outbreak of the Second Boer War in 1899. Churchill was captured by Boer commandos and held prisoner in Pretoria before plotting a daring escape across the country and eventually to safety in modern-day Mozambique. The incident made Churchill, who already enjoyed a famous name, a national celebrity in Britain and across much of the Empire, and he embarked on a profitable speaking tour recounting his experience.

But Churchill’s ambitions were not limited to military glory and journalistic scoops. In 1899, before his departure for South Africa, he contested and narrowly lost a by-election in Oldham, where he stood as a Conservative Party candidate. In the general election the following year, however, he won the seat, eventually taking his place as the Conservative MP for Oldham in the House of Commons in early 1901. While many would have wanted to toe the party line in their opening period as an MP, this was not Churchill’s style, and he increasingly spoke out against aspects of government policy he disagreed with. Over the ensuing months, Churchill became gradually more critical of his government and moved politically closer to the Liberal Party.

Churchill’s decision to finally shift allegiance from the Conservative Party to the Liberal Party came over the former’s support for economic protectionism, often referred to as ‘tariff reform’. As a convinced supporter for free trade, he could not support Joseph Chamberlain’s proposal to place tariffs on goods imported from outside the Empire. On 31 May 1904, he crossed the floor – to use the parliamentary parlance – and joined the Liberal Party. This was an ideological move, but it was also politically prudent. In 1906, the Liberal Party won a landslide election victory, and Churchill was resoundingly elected as the MP for his new constituency of Manchester North West. He had made tariff reform and his commitment to free trade a key component of his campaign. His slogan during the campaign was: ‘Vote for Winston Churchill and Free Trade.’1 With a majority of 1,241, Churchill was ready to begin his career in the Liberal government, and he was delighted to be appointed Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, which suited his interest in international affairs. Soon, he hoped, he would follow in his father’s footsteps as a cabinet minister and beyond.

The Manchester North West by-election took place on 24 April 1908, and it was brought about by Churchill’s ascension to the position of President of the Board of Trade. The fact a by-election had to take place was the result of a rule that had been in place since 1705 which decreed that whenever a new member was appointed to the cabinet they had to seek re-election in their constituency. Initially designed as an anti-corruption measure, it continued in varying degrees until 1926, and Churchill would become increasingly familiar with it as he moved in and out of cabinet in the coming years.

By the early 20th century, it was generally considered bad form to contest a ministerial by-election, and they were often unopposed. But Churchill was not so lucky. The Conservative Party announced that William Joynson-Hicks would contest the by-election in a bid to unseat Churchill. His problems were further compounded by confirmation that a Socialist candidate, Dan Irving, would also run, potentially pulling much-needed votes from the left away from Churchill.

Joynson-Hicks’ decision to run against Churchill despite convention can be explained by two key factors. First, many in the Conservative Party establishment remained resentful of Churchill, who they viewed as a traitor for his decision to join the Liberal Party in defence of free trade. Many remembered the self-promotion and unreliability of Lord Randolph and, believing Churchill was very much cut from the same cloth, wanted to trim him down to size. This is an early example of how Churchill’s family, personality and zest for self-publicity could incite resentment as well as awe. Here, he had so antagonised his former colleagues in the Conservative Party that they were determined to see him fail. In the coming years, it was these same traits that would see powerful men, such as the media mogul David Coupar Thomson, take against Churchill in Dundee. Secondly, despite his victory in the general election of 1906, Manchester North West was far from a safe Liberal seat. In fact, apart from Churchill’s recent victory, it had returned a Conservative at every election since its creation in 1885. With the issue of tariff reform on the wane, the Conservative Party therefore saw an opportunity to deliver a blow to a Liberal government still riding high after its landslide election victory two years before. For Joynson-Hicks, who Churchill had defeated at that 1906 election, this was also an early opportunity to regain the seat.

As is the case in most by-elections, a handful of niche issues – almost all of which hurt Churchill – came to dominate the short but intense campaign. The Liberal government’s Education Bill threatened protections for denominational schools and so was particularly controversial among the constituency’s Roman Catholic and Anglican populations. Churchill was also criticised by the constituency’s significant Jewish population, who pointed out he had failed – despite his promise – to reform the Aliens Act, which imposed large naturalisation fees on Jewish arrivals, many of whom were fleeing pogroms in eastern and central Europe. But while Churchill suffered grief on this issue, it is questionable how much it impacted the election. Joynson-Hicks, an inveterate anti-Semite, certainly failed to make any political capital out of it, idiotically declaring: ‘[I am] not going to pander for the Jewish vote.’2 Another issue Churchill had to face down was the Liberal government’s proposed Licensing Bill, which sought to curb the damaging effects of alcoholism and drunkenness by limiting the opening hours of pubs, but was stringently opposed by Manchester’s big brewers.

Despite these challenges, Churchill remained upbeat about his chances of retaining the seat. On his arrival in Manchester at the start of the campaign, Churchill claimed (using language he would later echo in reference to Dundee): ‘I am looking out for a safe seat and I think I have found one here in North West Manchester.’3 He also sought and secured permission from Asquith to confirm that the Irish Home Rule issue would be definitively addressed in the Liberal government’s second term. In the event, this appears to have had little truck with the constituency’s Irish voters, who may have been unmovable due to the pulpit pleading to oppose Churchill and the Education Bill. But it was an issue that Churchill felt particularly passionate about and – despite its failure to carry the day in this case – one that he would frequently return to.

Churchill therefore greeted polling day with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. The drive to get out the vote started early, with campaigners encouraged by the clear spring day. In a not-so-subtle campaign ploy, Churchill’s campaign hired a van emblazoned with posters showing a ‘large Free Trade loaf’ of bread alongside ‘the small loaf’ of Protectionism.4 This suggests that Churchill, at this point, put Liberal economic, rather than social, policies front and centre of his campaign. Churchill’s van was one of scores of vehicles that were draped in party colours, with many used to ferry voters to polling stations. Turnout looked to be high and, as polls closed, both campaigns knew the vote would be tight.

Churchill was the last candidate to arrive at Manchester Town Hall for the count. He was accompanied by his mother – then known by her married name, Jennie Cornwallis-West – and his younger brother, Jack. Jennie had been in Manchester for several days to try to drum up support for her son. Addressing one crowd on the eve of poll, she said: ‘I hear a good deal about dear coal, and dear beer. But what I say is: “Vote for dear Winston”.’5 Campaigning was not a novel experience for her. Jennie had practically run her sickly husband’s 1885 ministerial by-election in his constituency of Woodstock, earning a strong reputation both as a canvasser and as a platform speaker. Indeed, strong campaigning would be a common theme among the Churchill family women, with Clementine performing a very similar role for Churchill in Dundee.

As the trio entered the count in the famous Gothic building just after 9 p.m., Churchill was outwardly confident. The 33-year-old greeted the other candidates warmly and exchanged brief comments with the officials present. But despite this bonhomie, he was tense. Not only was his constituency on the line, but so too was his first cabinet job. When his agent, who had been monitoring the ballots as they were stacked on the tables, approached him, he knew the news was not good. Churchill had narrowly lost, and his political future was now very much an open question.

Despite what was clearly a devastating blow, Churchill’s reaction was one of magnanimity. Before the final result was even official, he approached Joynson-Hicks to concede defeat and offer his congratulations. ‘I must say, you are a real brick to say what you have done,’ a clearly taken aback Joyson-Hicks remarked after Churchill’s salutation.6 But Churchill’s generosity in defeat is not surprising. He had tasted defeat before – in Oldham in 1899 – although now, of course, the stakes were significantly higher. Yet, as a democrat, he always respected the verdict of the people, even if he often disagreed with it. As he explained some 24 years later: ‘I have nearly always had agreeable relations with my opponents . . . after [the election] is over, whatever has happened, one can afford to be good-tempered.’7 It is also the case that he had only been the MP for Manchester North West for two years. He had few ties there and, given his slim majority and the Conservative tendency in the seat, had – despite his public declarations of considering it a ‘safe seat’ – not expected to hold it indefinitely. He may therefore have already mentally adjusted himself to finding an alternative parliamentary seat in the future.

The Conservative hierarchy, however, was not as magnanimous in celebrating its victory. The Conservative-supporting Sheffield Daily Telegraph effervesced: ‘Churchill out – language fails us when it is most needed. We have all been yearning for this to happen with a yearning beyond utterance. Figures – oh! Yes, there are figures – but who cares for figures today? Winston Churchill is out, OUT, OUT! [original emphasis].’8 More cruelly still, a joke circulated of a stock exchange telegram supposedly sent to Churchill after his defeat: ‘To Winston, Manchester: What is the use of a W.C. without a seat?’9 While Churchill would surely have disagreed with the tone, he could not have disagreed with the sentiment.

After the result was confirmed, Churchill and his familial entourage made the short walk to the Manchester Reform Club to thank and console his supporters. Many of Lancashire’s Liberal elite would be there, licking their wounds, including the wealthy mill-owner, Gordon Harvey, MP for Rochdale, and Sir William Bailey, the engineer responsible for the Manchester Ship Canal. The Venetian-Gothic building – opened by Earl Grey, Gladstone’s Foreign Secretary, almost 40 years earlier and adorned with carvings of winged beasts – would have well matched Churchill’s dark mood. Yet, as he strode through the entrance, Churchill was handed an urgent telegram. It was sent from one George Ritchie and transmitted from Dundee.

Churchill later recollected that this telegram ‘contained the unanimous invitation of the Liberals of [Dundee] that I should be their candidate in succession to the sitting member’.10 He continued: ‘It is no exaggeration to say that only seven minutes at the outside passed between my defeat at Manchester and my invitation to Dundee . . .’ This is a nice and distinctly Churchillian anecdote, but it only tells part of the story. In fact, the decision of the Dundee Liberal Association was far from ‘unanimous’, as the membership was bitterly divided. Many were strongly opposed to Churchill taking the seat and were desperate to find a local candidate instead. But, in Ritchie, Churchill had by far the most able political mind in Dundee on his side – and he was determined to get the Dundee nomination for Churchill.

Chapter 2

The Road to Scotland

1908

Dundee was an attractive offer for Churchill, but it was not his only option. The constituency, which encompassed the entire metropolis on the banks of the Tay River in north-east Scotland, was a rare twomember constituency. This meant that, unlike most constituencies, voters in Dundee had two votes and elected two MPs to represent them. This form of representation had existed since 1868* and, given it was a particularly strong Liberal area, both seats had been occupied almost continuously by Liberal MPs since then. The only exception came at the most recent general election, in 1906, when a member of the forerunner to the modern-day Labour Party was elected for the first time. Nevertheless, Dundee remained an extremely appealing prospect for any prospective Liberal.

The vacancy in Dundee had arisen after the sitting Liberal MP, Edmund Robertson, who had been elected with a majority of more than 5,000 in 1906, was somewhat unexpectedly elevated to the House of Lords. Rumours quickly circulated that Robertson – who was charming and effective, but relatively undistinguished and sickly – had been given a peerage to create a vacancy for Churchill. There may be some truth in this – Robertson was certainly sad to give up his role as MP for the city – and the Morning Post noted there was ‘considerable surprise’ at the decision. But it would have been a highrisk strategy for the Liberal Party, particularly given the result in Manchester North West was not even known when Robertson was offered a peerage, nor was victory in a potential contest in Dundee certain. Indeed, Churchill’s own correspondence suggests that, if the Liberal Party had indeed arranged a by-election in Dundee, it was only one of several they had arranged on his behalf. He wrote on 27 April, three days after his defeat in Manchester and with only a whiff of exaggeration: ‘The Liberal Party is, I must say, a good party to fight with. Such loyalty and kindness in misfortune I never saw. I might have won them a great victory from the way they treat me. Eight or nine safe seats have been placed at my disposal already.’1 Certainly, had the Liberal Party really been determined to parachute Churchill into a safe seat, there were safer and more straightforward landing grounds elsewhere in the country.

Nevertheless, some in the local Liberal Party resented even the notion of receiving ‘second-hand goods from Manchester’, as The Courier, already proving itself a sceptic of Churchill’s commitment to the city, frequently described his rumoured candidacy.2 Many were still suffering from the trauma of the 1906 general election, when they had chosen – alongside the recently elevated Robertson – a London stockbroker, Henry Robson, to run as their second candidate. Robson, whose political experience to date had been as mayor of the Royal Borough of Kensington, was hopelessly out of his depth in the cauldron of Dundee politics, enduring a torrid campaign before slumping to defeat to Labour, despite a Liberal landslide across the country.

Yet in Ritchie – the Dundee Liberal Association chairman who sent a telegram to Churchill in the immediate aftermath of his defeat in Manchester North West – Churchill had both a skilful and determined advocate. The silver-haired 59-year-old was born in Kingsmuir, a small village to the north-east of the city, before moving to Dundee as an apprentice grocer in 1869. Ambitious and a hard worker, Ritchie began his own business 10 years later, eventually establishing a network of successful wholesalers in the city. But Ritchie’s primary interest was politics rather than money. A lifelong Liberal, he was first elected to the city’s council in 1889 and later won plaudits as treasurer, using his financial acumen to bring Dundee’s public finances into order. This was particularly notable because, in the words of one historian of the period, Dundee’s councillors were generally ‘seen as incompetent, sometimes corrupt and usually profligate with the public purse’.3 With a reputation as a successful businessman and competent administrator, Ritchie had quietly come to dominate the city’s Liberal caucus. Now he was determined to deliver Churchill the Dundee nomination.

There is little extant evidence available as to why Ritchie so favoured Churchill’s candidacy at this stage. The two went on to become extremely close – ‘one of the best friends I ever had’, according to Churchill4 – but there is nothing to suggest they had met or knew each other well before the 1908 by-election. A cynic might point to personal gain as a motive for Ritchie, particularly given he received a knighthood in 1910.* But this does not fit with his character or career to date, which had been marked by a commitment to public service and diligent business. What seems most likely is that Ritchie – a keen advocate for the city of Dundee – merely desired to secure a well-known and well-regarded politician as the city’s Liberal MP. As future events would show, Ritchie retained excellent political judgement and therefore probably anticipated that Churchill would go on to be a figure of major national and historical significance. To have Dundee associated with such a figure, he may well have thought, could only be a good thing.

Ritchie, therefore, got to work before Churchill had even fought the Manchester North West by-election, seeking to gain as much control of the nomination process as possible in case Churchill was defeated and could be tempted to Dundee. Here he had a problem: the standing orders of the Dundee Liberal Association called for the membership as a whole to shortlist and select candidates. An added difficulty was that the nominating process had to begin before Churchill was even available as a candidate. To make matters even worse, the anti-Churchill faction in the city was well aware of this fact and was therefore determined to speed up the process as much as possible. Ritchie, in turn, needed to ensure it went forward as slowly as possible to give Churchill a chance to become available for selection.

Unperturbed by these challenges, Ritchie used the imminent and unexpected by-election as a pretext to change the rules in his favour. Instead of all members having input into shortlisting, a six-member sub-committee would be formed to draw up a list of suitable candidates, which the membership could then vote on. While Ritchie superficially presented this as a drive to ensure efficiency, the more politically astute members sensed a sinister motive. Their ire was particularly focused on Ritchie himself, who had not only proposed the new sub-committee but promptly placed himself in charge of it as well. Negative but fundamentally correct briefings began to swirl in the Liberal Association – occasionally finding their way into the local newspapers – that Ritchie was attempting to keep the candidate vacancy open as long as possible in the hope of enticing Churchill to Tayside, should he face defeat in Manchester.

The membership’s resentment at their sudden and unexpected exclusion quickly evolved into outright dissension as it emerged this secretive sub-committee was, as they suspected, procrastinating in its only task – to find a suitable candidate. In the sort of timeless briefing that will be familiar to anyone involved in local party politics, one anonymous Liberal member launched a thinly veiled attack on Ritchie, telling The Courier that the failure to find a candidate was ‘just what might be expected from the caucus who attempt to rule the Association according to their own peculiar ideas’.5

Amid such hostile briefing, Ritchie was shrewd enough to know he could not just sit and do nothing, but at least needed to go through the motions of finding an alternative candidate. He first approached Charles Barrie, who from 1902 to 1905 had served as the Lord Provost – the ceremonial head of the local government – of Dundee. Barrie, a 68-year-old native of the city, was a self-made man, having served around the world as a commercial seaman before establishing his own shipping business in the 1880s back in Dundee. With money and a prominent local name, Barrie was a sensible – if unimaginative – choice. But Ritchie also knew that, as a man approaching 70, Barrie was unlikely to want to accept the stress of a tough by-election, or the arduous travel between Dundee and London that being an MP would entail. Indeed, Ritchie had approached Barrie to be the Dundee candidate in 1906, before the Robson debacle – but Barrie had declined then, citing old age. Clearly, Ritchie knew that Barrie, now two years older, was unlikely to feel any more inclined to take up the candidacy.

The next potential candidate sought out by Ritchie was John Fleming, who had been born in Dundee and was known to harbour political ambitions. He had already served as Lord Provost of Aberdeen between 1898 and 1902, while his brother, Robert, had made a fortune as an early pioneer of investment trusts in Dundee before going on to found the eponymous merchant bank, Robert Fleming & Co.* But, as Ritchie most likely anticipated, Fleming’s business and political connections now centred on Aberdeen, and he also declined to put his name forward. With the by-election growing ever closer, Ritchie continued to approach potential candidates. One was 40-year-old John Leng Sturrock, the son of Sir John Leng, who had himself been a Liberal MP for Dundee until 1906. Another was Liberal Association stalwart James Nairn, who may well have been aware of Ritchie’s manoeuvrings. Both declined.

Ritchie’s final approach was to yet another prominent local businessman, William Low. In 1870, Low had joined the management of the family’s grocers’ firm, which had been founded two years earlier by his brother, James, and William Rettie. The company, somewhat confusingly also named William Low – a fusion of the names of the two founders – had since expanded across Dundee.† With a private source of wealth – essential at this time, as MPs were unsalaried – and a local name, Low would have been another fine, if unimaginative, choice. And, unlike the others, he did not immediately rule out running. Instead, he said he would take some time to consider his options. As gossip spread that he was considering putting himself forward for the nomination – and confounding Ritchie’s best-laid plans – the anti-Ritchie faction rallied around Low. Responding to rumours that ‘a certain well-known local gentleman had undertaken to favourably consider’ seeking the nomination, a Liberal Association member told The Courier: ‘I only wish that he would, for it would take us out of a hole.’6

But just as it seemed his plans may have been thwarted, Ritchie received the news of Churchill’s defeat in Manchester North West – and his ready availability as a candidate. That night, without waiting for the approval of his fellow members, Ritchie rushed to send the telegram inviting Churchill to stand in Dundee. Now all he needed was for Churchill to accept.

But Churchill – much to the consternation of Ritchie – demurred on the offer. Ritchie’s telegram, perhaps revealing a twinge of selfdoubt at his own machinations, had urged Churchill to ‘wire if possible tonight’ with his intention to accept the offer. Instead, Churchill waited until the next day to respond and, even then, was lukewarm and non-committal. Arriving in London St Pancras by train just after 2 p.m., he told waiting reporters: ‘Nothing is yet settled with to my standing for Dundee or any other constituency.’7

It is easy to view Churchill’s failure to jump at the offer of the Dundee candidacy as a snub, or that he was somehow hesitant about being an MP in Scotland, but that would be a misreading. Ritchie was, given his own manoeuvrings, keen for Churchill to accept the offer immediately, but it was unrealistic to expect such a major decision to be made on the hoof and without time for proper consideration, particularly so soon after the defeat in Manchester North West. Indeed, far from being an insult, the delay arguably shows the gravity with which Churchill treated the offer.

The reality was also that – as a rising star in the Liberal Party, and as he had indicated in his letter of 27 April – Churchill had several attractive suitors aside from Dundee. The Merionethshire Liberal Association in north Wales wanted to offer him the candidacy in place of Osmond Williams, and this would have been extremely attractive to Churchill given the Merioneth constituency was effectively a rotten borough for the Liberals. It had been held by the party without interruption since 1868 and, for the last three elections, Williams had stood unopposed. Another potential safe harbour for Churchill was in the offing further south in Wales, with Liberal Party headquarters intimating it was in negotiation with John Philipps, the Liberal MP for Pembrokeshire, about standing down to allow Churchill to take his place. While Philipps enjoyed a majority of more than 3,000 – less than the current Liberal majority in Dundee – the seat had returned a Liberal member at every election since 1880, and the lack of a Labour presence there (unlike Dundee) would have also made it an attractive proposition.

Churchill’s indecision was, unsurprisingly, not well received in Dundee. This was largely a question of civic pride, which was justifiably wounded by Churchill’s prevarication. Following reports that he had not immediately accepted the Dundee invitation, gossip quickly circulated the city that Churchill was determined to ‘look this gift horse in the mouth’.8

Churchill finally accepted the Dundee Liberal Association’s invitation on 28 April, some 72 hours after it had initially been offered. During the intervening period, he had taken counsel from close friends and Liberal politicians, including Asquith, on the sagacity of taking up Dundee’s offer, not all of which was positive. The editor of The Westminster Gazette and a regular confidant of Liberal politicians, John Spender – better known by his initials J.A. – strongly advised Churchill against accepting the Dundee nomination. ‘Don’t go to Dundee unless you are sure of your Scots,’ he advised in a letter to Churchill on 25 April, adding ominously: ‘They are queer folk.’9 Churchill, however, would not be put off and, having made the decision to stand, was exuberant at the prospect of having secured such a seemingly safe seat. Writing to his mother the day after he accepted the nomination, he said: ‘They all seem to think it is a certainty – and even though a three-cornered fight will end in a majority of 3,000. It is a life seat and cheap and easy beyond all experience.’10

Dundee’s Liberal Party members gathered on 28 April to accept Churchill’s nomination, in what was effectively a Ritchie-engineered fait accompli. Having agreed to send a message of condolence following the death of the former Liberal Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, who had died the previous week, Ritchie rose to inform the members of Churchill’s response. Cognisant of his own machinations, Ritchie was keen to stress that he had gone to every effort to secure a local champion, speaking to no fewer than six prominent individuals – for good measure, he suggested that he himself had considered running – but without success. Then came the ‘unexpected’ news from Manchester North West and the opportunity to recruit Churchill, a national figure, as their candidate – an opportunity Richie had immediately seized. The decision to approach Churchill was, he recognised with more than a touch of political spin, the ‘implied rather than expressed’ will of the Liberal Association.11 Nevertheless, the offer had been made, and Churchill had accepted it.

If Ritchie had hoped this would be enough to satisfy the more restive association members, he was mistaken. Party member Alex Gow immediately rose to demand Ritchie release the names of the local figures he had approached to run, implicitly suggesting no such conversations had taken place because Ritchie wanted to recruit Churchill all along. Despite attempts among some members to howl Gow down, Ritchie agreed to release the names of those he had approached. In a final coup de grâce, Ritchie confirmed that William Low had actively considered standing, until he had discovered earlier that morning that Churchill would also be seeking the nomination.

Yet, despite all Ritchie’s efforts on his behalf, Churchill was still unhelpful. On receiving confirmation of his nomination on Tuesday 28 April and an invitation to come to Dundee that Friday – three days later – Churchill responded: ‘But why not Monday?’12 Such a casual response made even Ritchie baulk, and – in the first of several such interventions – he rushed to protect his champion’s reputation and persuaded Churchill to agree to arrive on the Friday after all.