Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

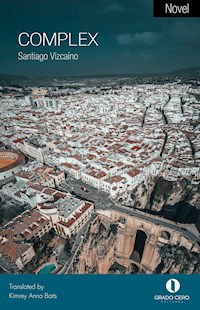

- Herausgeber: Grado Cero Editores

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Complex follows the life of Willy, an Ecuadorian writer and student on scholarship in Malaga, Spain. In a wry and self-deprecating tone, the novel provides a first-person account of life as an Ecuadorian migrant in Spain. This fragmentary and often poetic meditation on the Ecuadorian identity crisis, and on the ways in which it intersects with masculinity and machismo, does not shy away from making the reader feel by turns amused and repulsed: Willy is a character who is difficult to love yet impossible to hate, a dizzying contradiction of removed analysis and unbridled emotion, of self-awareness and instinct. Willy's misadventures take him to strange and at times disturbing places, and this is not the stereotypical tale of life as a migrant. Rather—as the title hints at—it is something more obscure, more convoluted, more complex.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 106

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

I

and all I wanted was to see the ocean in Malaga. I had the pilgrim’s notion that you could see Africa from its shores. qué huevón. I’ve been in Madrid for two days, and I am scared. scared of the thousands of eyes appraising me from above like some rare breed. if there weren’t so much fucking ecuatorianito here, I think it’d be different. I might even pass for a piece of folk art. but no. in Madrid, it starts to get cold, te cagas, and here I am in this shitty suit jacket like a cultured thief. better put, like a Chinese-suit–jacketed thief. because in Ecuador, everything they sell to you as “american” or italian or french is Chinese. even what you get in the shoppings, the worst really: do not wash in washing machine; do not expose to direct sunlight; do not iron at high temperatures. how the hell do you pay a hundred and fifty for a suit jacket if the mere act of donning it causes damage? to the jacket and to you. and so on.

in Madrid, you feel like a strange bird. scratch that: like a brown piece of shit on the royal palace’s sidewalk. and the cold isn’t the “achachay” of quito. no. here, it burns your eyes and pierces your lungs. but the cold passes. the elegance of these huevones is so unbearable that you understand how moctezuma must have felt when confronted by cortez’s lead. the worst is that it all sticks to you, and in two hours, you’re already saying macho and joder and que te den por el culo. saying, “fuck you up the ass,” like it’s nothing. but in Madrid, you’re still the Chinese-suit–jacketed weirdo. Like a dead rat in Caracas, there in el callejón de la puñalada. What’s perhaps surprising is that an andean latino who ought to be cleaning tables is dressed like this: a sort of neo-baroque dandy. a unique specimen who sits down to eat twenty-euro pork shoulder and potatoes. the fucking potatoes they never would have eaten if they hadn’t raped my great-grandmother. everything I think is, of course, subnormal: sub-developed, sub-terranean, sub-urban. but the words escape my throat, and I say them to a Chilean immigrant who gives me a look like I’ve offended her.

the thing is, it’s muy jodido to live in Madrid. my whole panorama is the following: hostel basement in san mateo, number twenty in front of the museum of romanticism. the high heels of Spanish women who talk too fast and walk by too fast in their silken pantyhose. well-mannered children who say, “que se ha machao, madre”; “mother, it’s stained!” la puta que les parió, fuck the cunt who begat them. and once more, I feel like the underdeveloped sudaca who thinks himself somewhat cultured but has no one to talk to about literature or film or music or about anything. that’s why it’s been such a blessed relief that they play Spanish porn on TV at midnight. my first time making love to a Spanish woman. it’s a saying. to quote fogwill, “the love was already made.” in Ecuador, it’s all youporn with swiss, poles, russians, and romanians. a great mass of blondes who must have come out of a flea market, but so long as the end purpose is served, who really cares?

my uncle lives here. he’s a migrant. he rents out this cold basement and sublets it to a Chilean and an Ecuadorian who show up about twice per week. migration is an underworld. Ecuadorians here are like a plague. they’re also useful. they do what everyone knows how to do, what the spaniards don’t want to do, or what they must do in accordance with their level of poverty. Ecuadorians here suffer from a vital schizophrenia: mind divided, living off nostalgia. but they’ve also gotten used to the comfortable life offered by this strange so-called “first world.” when they return to Ecuador, they feel out of place. they speak differently. dress differently. they even regard their roots with contempt. it’s a rematch: the racism they suffer here, they bring back to take out upon their own, redoubled. the Ecuadorian identity crisis transforms immigrants into cultural monsters.

my uncle works in hospitality, waiting tables and washing dishes at a seafood restaurant. people wait in endless lines to get in the place. this means I’ve been able to eat odd things like razor clams and barnacles and brown crab. I’ve also tried callos a la madrileña: beef tripe stew, or what we call guatita in Ecuador. but the best, by far, is the wine. everyone knows that. for a euro, you can buy a harsh, sour wine that would cost you ten dollars in Ecuador. everyone knows that.

I’ll be here just three days. even so, I’ve managed to grasp some idea of this world. I’m far more interested in the lives of the characters known as immigrants. the spaniards are highly predictable. extremely conservative. they are quite smart about exploiting the tourists, but that’s another story. south americans in general are a richer phenomenon. their condition has turned them into something more complex. their own language has mutated in an extremely odd way. it’s laughable to listen to them saying tío, joder, macho, que te den por el culo alongside their own cultural idioms. the Ecuadorian and the bolivian stand out the most in this jungle. they’re savage drinkers. the few resting places they have are dedicated to drinking beer: whichever’s strongest. they take refuge in their apartments with a steadfast determination for self-destruction. fights are, thus, frequent. and jealously. the sexual explosion in their (our) countries is sinful. oh, spain, remove your sex from me.

I’m no immigrant. I don’t want to be an immigrant. I regard them with ire. but I find myself obliged to enjoy their delirium. there are those who want to return and those who don’t. the former retain a sense of self out of nostalgia. the latter have mutated. they have no idea what they are. or perhaps they do—they’re not going back, and in that resignation lies their conversion into spaniards. the others will never manage to adapt. they work themselves to the bone to send back remittances and forever think of Ecuador as the promised land. for them, it’s a struggle, a lucha. work is a sacrifice. those who gave up live for the day and day-to-day. they want to bury their past. generally speaking, they’re the younger ones. they want to be included. they go out with spaniards. dress like them. eat like them. they tend to regard Ecuador with distain. they’ve “grown.”

my uncle’s friends run the gamut from one extreme to the other. there’s one, for example, who’s from one of those coastal Ecuadorian towns where poverty and violence wound the days and envelop the nights. he lives with a bolivian woman in a study in the center of Madrid: a single room that serves as bedroom, living room, dining room, and kitchen, normally occupied by students. the woman is fat and indianized and won’t stop talking about the tragedy of her job with a smelly old man that she puts up with all day. one of those unbearably racist spaniards. she’s fed up, but a good person.

we have ceviche for dinner. every good costeño knows how to make a good ceviche, my uncle says.

“how long have you lived here?” I ask.

“I came fifteen years ago and haven’t been back to Ecuador,” he responds. “they don’t like me there, ñaño. if I show up, they’ll kill me. some sons of bitches swore it to me. I put three bullets in a careverga who was screwing my woman. so, I stay here. I don’t want problems. I’m rehabilitated, my bróder. why don’t you have a drink? do you like wine?” and he takes out a bottle of marqués de cáceres nipped from the restaurant he works at.

that’s what my uncle’s friends are like. all with sad stories to hide. they’ve buried their pasts. those who go back go only for a few months because they’re not used to it anymore. their country—our country—is precisely an imaginary line, a space filled with abandoned women and children. or, in the case of the women who left, with abandoned men. be in Spain and long for Ecuador, be in Ecuador and long for Spain. that mental divide turns them into acculturated cabrones.

I already know that two or three nights aren’t enough to fully understand a way of life, but this has been my first impression. my first contact with what would be called “my own kind.” like the last night before leaving for the mediterranean. we go to a disco in south Madrid. it is sunday, and I can’t believe it. in Quito, sundays make you want to kill yourself. nothing’s open. people flee, hide indoors. here, sunday is the day immigrants go out on the town, because many of them have mondays off: blessed day of the hangover, the resaca, the chuchaqui, the guayabo, the ratón, the cruda. sunday nights fill with the scent of sudaca cologne. the women go out heavily made-up, in snug dresses they’ve bought on sale or wearing out-of-style, fake-leather jackets. it’s like being in the eighties. even the music they dance to is about thirty years out of date. they live off pure nostalgia. it’s fucked up, but such great fun. they dance pressed tightly against their dance partners, while the tables fill with pails of beers and bottles of rum.

salsa, perhaps, then cumbia, then bachata, and to top it off, some reggaeton or vallenato. they’re eating it up. it’s like a quinceñera party. the men have gelled-back hair and colored shoes and flowered shirts to attract attention. there’s almost always a gold chain gleaming against their bare chests. it’s like kusturica’s underground but with south americans. young and old, all sharing in the same tastes. there’s consensus. here, no one has issues unless you look at their girl. or their guy.

there are three of us sitting here, with an insatiable desire to drink because it’s my last day in Madrid. my uncle insists that I ask a girl to dance and take her back home with me. “no problems here, loco,” he says, “it’s all easy. they’re all crazy to fuck.”

I laugh enthusiastically and tell him to wait, be patient, that I’m not that fired up just yet. and we toast to the joy of seeing one another after all these years. we’re friends now, we’ve moved over and beyond blood ties.

“to that, cheers. come whenever you want, ñaño. my house is humble, and it is yours.”

“thanks, brother, I’ll be back.” and so on.

then I see one of the guys who’s with us, also Ecuadorian, get up and go over to another table where there’s a girl sitting alone and ask her to dance. he draws her against his body but clearly has no idea how to follow the rhythm. it’s cantinflas-esque. she tries to pull away, pushes him a bit, and he says something into her ear and she laughs. she’s brown-skinned, long-nosed, wearing a turquoise dress with some type of flower over her right clavicle. she has mid-forehead bangs that suit her quite badly. she’s terribly unattractive, but her ass is terrific. the guy looks at us and winks. we laugh.

suddenly, a man approaches our friend and shoves him to the ground. our friend picks himself up and they begin to squabble. we stand up from the table to get a better look at what’s happening, and kicks and punches start flying every which way. I take shelter to one side to observe the action. I see my uncle in the center of the dance floor, defending himself with a beer bottle. I come up behind him and take hold of his shoulders to calm him down. the bouncers arrive and throw us out of the disco, shoving us roughly through the door. just like that. the night ends in the middle of Madrid with a bottle of whiskey and laughter. all would seem normal.

II