Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Regardeur

- Sprache: Deutsch

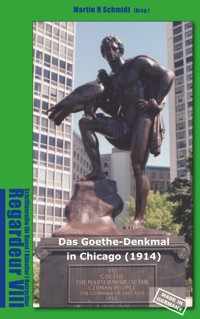

Das Goethe-Denkmal von Hermann Hahn in Chicago. To the Mastermind of the German People. MADE IN GERMANY Die hier zusammengetragenen Zeitdokumente und eine aktuelle Betrachtung zeichnen die 100jährige Geschichte des größten, figurativen Goethe-Denkmals nach, das am 14. Juni 1914 in Chicago der amerikanischen Öffentlichkeit übergeben wurde. "Das einzig mögliche Mittel, die Idee des Weltfriedens zu fördern, ist darin zu finden, dass sich die Völker selbst einander besser verstehen und würdigen lernen. Das dem grössten deutschen Genius geweihte Standbild soll in der Wunderstadt des Westens ehrenvolles Zeugnis geben von deutscher Geistesarbeit und deutscher Kunst." Mit diesen Worten pries der Münchner Historiker Dr. Karl Theodor von Heigel das Goethe-Denkmal von Hermann Hahn kurz vor dessen Abtransport in die USA. Nur wenige Wochen vor dem Ausbruch des 1. Weltkrieges eingeweiht, ist das Goethe-Denkmal von Hermann Hahn Prototyp und Vorbild für monumentale Skulpturen in amerikanischen Großstädten; ohne diesen Goethe würden die Großbronzen von Picasso, Calder, Miro und Flanagan wohl nicht in Chicagos Innenstadt stehen.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 189

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHICAGO

HOG Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the

Nation‘s Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling

City of the Big Shoulders

Carl Sandburg, 1913

MÜNCHEN. Wie schon mitgeteilt, sind aus dem Wettbewerb um ein Goethedenkmal für Chicago Hermann Hahn, Hugo Lederer und Hubert Netzer als Preisträger hervorgegangen.Zwischen Hahn und Lederer schwankte lange die Wahl, endlich entschloß mansich, HahnsEntwurf auszuführen. Er ist plastischer. Das mag entschieden haben. Hahns Entwurf knüpft an das Wort an: „Er nahm an sich Adlerflügel“. Ein Ephebe von wundervoller Körperschönheit mit Goethes Gesichtszügen hält einen Adler auf dem hochaufgesetzten Knie. Ohne alle Symbolik, ein „Zustands“-Werk und doch von überwältigender Wirkung, wenn man bedenkt, daß diese prächtig silhouettierte Gestalt in dreifacher Lebensgröße ausgeführt werden soll und auf einen gewichtigen Sockel zu stehen kommt, der sie über das Menschengewimmelerhöht, ohne sie ihm völlig zu entrücken. In Hahns künstlerischem Entwicklungsgang bedeutet dieses Hauptwerk eine entscheidende Zäsur.

„Die Kunst“, München, 27. Oktober 1910

Der Mittlere Westen wurde wie kein anderer Teil der USA zur neuen Heimat für deutsche Einwanderer. Zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts gaben in Chicago etwa eine halbe Million seiner Bürgerinnen und Bürger an, dass sie entweder selbst oder dass zumindest einer ihrer Elternteile in Deutschland geboren waren. Das entsprach rund einem Viertel der gesamten damaligen Bevölkerung Chicagos. Mit der Zuwanderung fanden zugleich deutsche Kultur und Traditionen Eingang in die damalige US-amerikanische Gesellschaft, die in mannigfaltiger Weise sichtbar wurden und es teilweise auch noch heute sind.

In diesem Zusammenhang kommt der Kunst eine bedeutsame Funktion zu. Sie half unter anderem den deutschen Einwanderern die Verbindungen zu ihrer Heimat, dem Deutschland, das sie aus unterschiedlichsten Gründen hinter sich ließen, aufrecht zu erhalten.

Grußwort

Dr. Martin H Schmidt nimmt sich in vorliegender Publikation einem dieser Kunstwerke an. Zum 100. Jubiläum ihrer Errichtung im Chicagoer Lincoln Park berichtet der Autor über die in Deutschland gegossene Goethe-Statue. Auf anschauliche Weise widmet sich dieses detailreiche Werk der Geschichte eines durchaus ungewöhnlichen Beispieles deutscher Bildhauerkunst in den USA im Kontext der deutschen Zuwanderung nach Chicago und im Wandel der vergangenen 100 Jahre.

Das Denkmal war und ist ein Beispiel deutsch-amerikanischer Verbundenheit und Freundschaft. Dem Autor sei Dank, dass er die spannende und lebendige Geschichte dieses Goethe-Denkmals nachgezeichnet hat.

Dr. Christian Brecht

Generalkonsul der Bundesrepublik Deutschland

Chicago, Dezember 2013

Contents

Grußwort

Generalkonsul Dr. Christian Brecht

Introduction and summary

Einleitung und Zusammenfassung.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Goethe.

The initiator

Der Initiator.

The sculptor

Der Bildhauer.

The material

Das Material.

The transport

Der Transport.

The Idea

Die Idee.

Dr. Martin H Schmidt

Translation

by Christine Galavielle, Paris

Dokumente im Originalwortlaut:

Die Geschichte des Goethe-Denkmales für Chicago

Harry Rubens

Die Festliche Besichtigung in München

Anonym

Das Goethe-Denkmal fuer Chicago – Das moderne Denkmal

Fritz Stahl

Schiller and Goethe

Harry Rubens

Die Jury

Harry Rubens

Gesicht und Geschichte des Erzes

Alexander Heilmeyer

Die Kgl. Erzgiesserei als Privatanstalt (1873-1924)

Simon Miller

Sonntagspost Chicago, 14. Juni 1914 (Auszüge)

Anonym

Zeitlinie

Literaturverzeichnis

Abbildungen

Danksagung / Acknowledgment

Introduction and summary

For the 100th Jubilee of the Erection of the Goethe Monument by Professor Hermann Hahn in Chicago

The Goethe Monument by Hermann Hahn in Chicago is one of a series of monument erections that started during the eighties of the nineteenth century. German emigrants coming from the West and urbanizing the American prairie, creating settlements while remaining conscious of their roots, initiated erections of monuments as a remembrance of their home culture and of their own achievements. The link to Germany was still strong enough, whereas confidence in American art had not yet grown, so that orders for sculptures went to German artists and orders for technical founding went to German foundries.

What was created here was the export of German art of monuments and founding technique, the traces of which can be found distributed over the five continents. Due to its colossal dimension and its experimental conception, the Goethe monument in Chicago represents the apogee of this development, but at the same time we must consider this monument as the latter portion, the twilight of the gods by way of monumental personal sculptures, in Germany as well as overseas.

On September 27the of 1913, the then highest bronze monument of the prince of poetry Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, was presented to the public in the Royal mineral foundry von Miller. Among the important number of invited guests, there was the Bavarian Prince Regent Ludwig III, who would not have foregone the personal inspection of this monument about which so much had been said and written prior the its erection. The connective spirit, the symbolic bridge between the old and the new world was underlined many times on the occasion of the official speeches on the day of presentation; indeed, the monument was not to be placed on German ground, but for America, more precisely for Chicago.

German emigrants, regrouped in a multitude of associations, above all located in the north of Chicago, wanted to erect a monument bearing witness to them and to their attachment to their home country. After the statues for Friedrich Schiller (1886), Alexander von Humboldt (1892) and Fritz Reuter (1893), there figure who was in their opinion the most important hero of German thinking: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. “The Mastermind of the German People”, as it can be read on the front of the pedestal. As to the number of monuments donated, the Germans were on the forefront of other nations, which was in conformity with the inflation of documents during that time, and also with the percentage of German inhabitants in comparison with other immigrants from Ireland, Great Britain, Italy and Poland. “ The Germans of Chicago” inaugurated on the 16th of June 1914 the highest personal bronze monument in North America, in the northern part of the Lincoln Park of the City. The festive act was watched by a crowd of some twenty thousand visitors, a majority of German descent. Pouring rain could not prevent them from being present during the three hours of the ceremony. Admiring speeches were held, German songs brought forward by the numerous association and chorals of singers, and a march of participating associations in their multi-colored costumes mqarked the end of the festivities. Only some weeks later, the First World War started in Europe.

How had the erection of this monument been conceived?

When on the 31st of March 1876 the “Swabian Association” was founded, it was the first association founded by German immigrants in Chicago. The objective of the “non-profit organization” should be as follows: To keep alive the festivities and customs of Swabians having come from Swabia, to acquire land and mutually help and support each other. Obviously, the erection of monuments was part of this effort, and as one of the first personal monuments in Chicago, the replica of the Schiller monument by Ernst Rau in Marbach, had been built under the responsible leadership of the Swabian Association. The Association and its members were also part of the realization of the the Humboldt monument that was already mentioned, and also of the Reuter monument. All the three statues are somewhat taller than life-size and appear in historic outfit; they are in accordance with the usual monumental style of the German Emperors, and they also agree with the interpretation of art as it was emerging in America which is reflected in particular in the public sculptures of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Without a preceding public tender, the German sculptors had received their orders directly, and the bronze casting were done in German foundries: “MADE IN GERMANY”.

As early as 1889 the board of the Swabian Association had planned the erection of a statue of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. However, this time there should be a special monument, for which reason the project was postponed for years. Finally, a committee for the monument was instituted under the direction of the Chicago lawyer Harry Rubens. On the occasion of several trips to Europe, Rubens had far-reaching consultations with artists, directors of museums and other authorities, whereupon an international Jury invited eight sculptors from Germany, with German background and from Austria, to enter a competition. Each one of those invited should receive a uniform prize money, and the winner was to conduct the execution of the monument. The idea was to create an independent monumental sculpture representing by way of an allegory the genius of the prince of poetry to be honored, not one more bronze doll in traditional garment as part of the existing series.

In the rooms of the Royal Academy of Arts in Berlin, during two days of meetings, the founder, artist and director of the Royal Academy of Arts Ferdinand von Miller (Munich), the sculpture of animal August Gaul (Berlin), the sculpturer or German origin Karl Bitter (New York), the architect Frederick A. Ohmann (Vienna) and Harry Rubens discuss the projects of Adolph Bermann(Munich), HermannHahn (Munich), Anton-Hanak (Vienna), Hugo Lederer (Berlin), Hubert Netzer (Munich), Othmar Schimkowitz (Vienna), Georg Wrba (Dresde), Albert Jaegers (Suffern, N.Y.) and HansSchuler (Baltimore, Md.) After tough negotiations, but in the end unanimously, the Jury decided in favor of the project by Hermann Hahn.

In order to have the public in Chicago participate, the initiators organized an exhibition of all the art models in the Art Institute of Chicago at the beginning of the year 1911. The selection process had been praised as one of the most diligent and most thoughtful by the press, as well as its result. Furthermore, preliminary models were to be circulated in the most important cities of the USA; the initiators were so convinced of their project that they envisaged the realization of the other seven designs. The beginning of the war prevented this plan.

The realization finally agreed upon was the design of a monument which was blatantly different in comparison of all preceding personal monuments in Germany. And one would like to say: inadmissible for a site in Germany, but from the German perspective looking at the other side of the Atlantic it was certainly justified.

“He beheld an eagle’s wings”, under this motto Hahn presented an ephebe of immaculate physical beauty who rather makes one think of antique athlete statues or statues of Zeus, than of Goethe. An eagle sits on his elevated right knee, a broad scarf, a chlamys, covers the hips, is turned around the neck and falls in a light swing on the back. The monument was meant to be symbolic, and symbolic it is, because nothing of this colossal statue almost 6 meters high recalls the Early Victorian style image of Goethe that had left the mark of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe on generations. But obviously the experiment went too far even for the artist. A rest bank in granite with a prominent high relief of the old Goethe is situated in the back of the monument. It is somewhat reminiscent of the classical image of Goethe.

Cast in bronze, resting on granite, this is how, according to the wishes of the donors the colossal monument of Goethe should rest here while bearing witness to centuries of German culture and German performances, both spiritual and technical. However, the first 90 years experienced highs and lows. Just a few years after the inauguration, when the USA had just entered into the First World War, the Chicago Herold wrote that the Goethe monument embodied “naked violence and German militarism”.

As a consequence, the members of the Park Committee wanted the destruction of the statue, or at least a change of place for the monument. This first attack on the monument was blocked by art lovers in Chicago with loud protests.

If protests against the Goethe monument and thus against Germany had been of a rather literary nature during the First World War, they became more direct during the Second World War. Aggressions targeting the monument took place, without being capable of seriously damaging the bronze.

What the anti-war demonstrators had not succeeded in doing, that is to lift the monument from its base, nature managed this during the night of the 13th September 1951. During a thunderstorm at night, a flash of lightning hit the statue at 1:45 hours and smashed the left foot, the supporting leg of Goethe. Six German associations joined under the leadership of the architect Albert C. Fehlow, in order to donate the sum required for the repair. The imposing granite base remained an orphan for almost three years, and on the 13th of July 1954 the repaired monument could once again be placed where it had been, with a new left foot, having been sandblasted and provided with a new patina.

An entirely new interpretation was received by the Goethe monument during the winter of 1979. The monument did not reflect violence and militarism, but the contrary: high-minded youth and beauty. The naked statue only covered with a towel became a paradigm of liveliness and eroticism, at least during one night when it was chosen as the meeting place of a night watch organized by an association of Chicago homosexuals.

Queers and lesbians were quite obviously at ease under the wings of Zeus and Goethe.

For the year 2000 the Chicago Park District responsible for parks and sculptures therein, ordered a general cleaning of the monument. Once again, the monument was lifted from its base. Under the direction of chief restorer Andrzej Dajnowski, it was possible to find remnants of patina from the time of its creation that could be selected as the basis for the new surface color. A strong brown color, almost like milk chocolate, makes the monument has been glistening by now for some years and bears witness to the aesthetic inclinations of Munich sculpture art at the beginning of the 20th century. At the same time, this shows ways of handling urban furniture, in a careful and preventive manner that can be observed unfortunately only in its very beginning by the German authorities entrusted with the protection of monuments, as sculptures in the public sphere are treated in Germany almost with disdain.

However, Hermann Hahn’s colossal statue influenced new schools of art. Not just in Germany, nor only with regard to personal monuments, but also concerning free artistic work rising in monumental ways and that were erected in the center of Chicago since the seventies. Colossal pieces of work manufactured after sculptures by Pablo Picasso, Jean Dubufett, Joan Miro, or giant sculptures like the Stabile by Alexander Calder and the two dancing bronze hares in black patina by Donald Flanaggan in the John Hancock Center. Without Goethe’s monumentalism and without his pioneer roll, these giant sculptures would hardly have found a place in public life in Chicago.

Now, on the occasion of the 100th Jubilee of the erection, we have to honor this monumental sign of German-American friendship and to show once more to Americans and Germans how strong the cultural, social and friendly links of both countries, cultures and people have been for many generations and still are and will certainly remain as such in the future.

This publication may and will grow further. The compilation of historical documents and explaining articles at first occupied the front line, in order on the one hand catch the spirit of the time around 1910/1914, but also to offer an embedding of the whole project into the historical context of the present. The next step will be the translation of the texts into American English, so that the American side will also dispose of the information concerning the Goethe monument. Beyond this, contributions by colleagues and specialized journalists are explicitly desired and very much asked for, in order to allow the “Goethe Monument” to progress and and as a symbol confirm German-American friendship, to keep information, develop exchange and to come to know each other by respectful conversation.

„Let us tenderly and kindly cherish, therefore, the means of knowledge. Let us dare to read, think, speak, and write.“

John Adams (2nd President of the United States)

„To be faithful to ourselves, we must keep our ancestors and posterity within reach and grasp of our thoughts and affections, living in the memory and retrospect of the past, and hoping with affection and care for those who are to come after us.“

Daniel Webster (US-Senator and Secretary of State)

Einleitung und Zusammenfassung.

Zum 100sten Jubiläum der Errichtung des Goethe-Denkmals von Prof. Hermann Hahn in Chicago

Das Goethe-Denkmal von Hermann Hahn in Chicago befindet sich in einer Tradition von Denkmalssetzungen, die in den achtziger Jahren des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts begann. Deutsche Emigranten, die von Osten her die amerikanische Prärie urbar machten, Siedlungen schufen und dabei ihrer Wurzeln gewahr blieben, initiierten Denkmalserrichtungen, als Erinnerungsstätte an die heimatliche Kultur und an eigenen Leistungen. Die Verbindung nach Deutschland war noch stark genug und das Vertrauen in die amerikanische Kunst noch nicht gewachsen, sodass die bildhauerischen Aufträge an deutsche Künstler wie auch die gusstechnischen Aufträge an deutsche Gießereien gingen.

Was hier entstand, war der Export deutscher Denkmalskunst und Gusstechnik. Ein Phänomen, dessen Spuren sich über die gesamten fünf Erdteile verteilt nachweisen lässt. Das Goethe-Denkmal in Chicago stellt mit seiner kolossalen Größe und seiner experimentellen Ausrichtung den Höhepunkt dieser Entwicklung dar, gleichzeitig aber müssen wir in dem Denkmal den Abgesang, die „Götterdämmerung der monumentalen Personenplastik“ sehen; in Deutschland, wie in Übersee.

Am 27. September 1913, wurde in der Kgl. Erzgießerei von Miller in München, das seinerzeit größte Bronzedenkmal für den Dichterfürsten Johann Wolfgang von Goethe der Öffentlichkeit vorgestellt. Unter der Vielzahl geladener Gäste war auch der bayerische Prinzregent Ludwig III. Er ließ es sich nicht nehmen das Denkmal, über das im Vorfeld der Entstehung bereits so viel geredet und geschrieben wurde, persönlich zu besichtigen.

Das Verbindende, der Brückenschlag zwischen Alter und Neuer Welt, wurde wiederholt in den Festreden des Besichtigungstages herausgestellt; denn, das Denkmal war nicht für deutschen Boden bestimmt, sondern für Amerika, genauer: für Chicago.

Deutsche Emigranten, zusammengeschlossen in einer Vielzahl von Vereinen, vornehmlich angesiedelt im Norden Chicagos, wollten sich und ihrer Verbundenheit zur Heimat ein weiteres Denkmal setzten. Nach den Standbildern für Friedrich Schiller (1886), Alexander von Humboldt (1892), Fritz Reuter (1893) und Ludwig van Beethoven (1897), nun dem ihrer Meinung nach größten Heroen deutschen Denkertums: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. „The Mastermind of the German People“ wie auf der Sockelvorderseite zu lesen ist. Mit der Anzahl der von ihnen gestifteten Denkmalen waren die Deutschen Spitzenreiter vor anderen Nationen, was der Denkmalsinflation der Zeit im Heimatland entsprach, wie auch dem prozentualen Anteil deutscher Einwohner im Vergleich zu anderen europäischen Einwanderern aus Irland, Großbritannien, Italien und Polen. „The Germans of Chicago“ weihten am 16. Juni 1914 das größte bronzene Personaldenkmal Nordamerikas im nördlichen Lincolnpark der Stadt ein. Den Festakt verfolgte eine Menschenmenge von circa 20tausend vornehmlich deutschstämmiger Besucher. Strömender Regen konnte sie nicht davon abhalten, der gut dreistündigen Zeremonie beizuwohnen. Lobesvolle Reden wurden gehalten, deutsches Liedgut von den vielen Sänger-Vereinen und Chören zu Gehör gebracht, ein Umzug der beteiligten Vereine in ihren farbenprächtigen Trachten schloß die Feierlichkeiten ab. Nur wenige Wochen später brach in Europa der 1. Weltkrieg aus.

Wie kam es zu dieser Denkmalssetzung?

Als am 31. März 1878 der „Schwaben-Verein“ ins Leben gerufen wurde, war es die erste Vereinsgründung deutscher Emigranten in Chicago. Das Ziel der „non-profit-Organization“ sollte werden: „Die Feste und Brauchtümer der Schwaben vom Schwabenland aufrecht zu erhalten, Grundeigentum zu erwerben und sich gegenseitig zu helfen und zu unterstützen.“ Offensichtlich gehörte auch die Errichtung von Denkmälern dazu, denn eines der ersten Personendenkmale in Chicago, eine Replik des Schiller-Denkmales von Ernst Rau in Marbach, entstand unter der federführenden Leitung des Schwaben-Verein. Auch an der Realisierung des erwähnten Humboldt-Denkmals und des Reuter-Denkmals waren der Schwaben-Verein und dessen Mitglieder beteiligt. Alle drei Statuen sind etwas über Lebensgröße gearbeitet und in historischem Gewand gegeben; sie fügen sich ein in den gängigen Denkmalsstil des deutschen Kaiserhauses, wie auch in die sich in Amerika herausbildende Kunstauffassung, die besonders in den öffentlichen Skulpturen des Augustus Saint-Gaudens präsent war. Ohne Ausschreibung eines Wettbewerbes waren die deutschen Bildhauer direkt beauftragt worden, die Bronzegüsse erfolgten in deutschen Gießereien: „MADE IN GERMANY“.

Bereits 1889 plante der Vorstand des Schwabenvereins die Errichtung eines Standbildes für Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Diesmal jedoch sollte ein besonderes Denkmal entstehen, wodurch sich das Projekt um Jahre verzögerte. Ein Denkmalkomitee bildete sich schließlich unter der Führung des Chicagoer Rechtsanwaltes Harry Rubens. Rubens führte auf mehreren Europareisen umfangreiche Konsultationen mit Künstlern, Museumsdirektoren und anderen Autoritäten, woraufhin eine international besetzte Jury acht deutsche, deutschstämmige und österreichische Bildhauer zu einem Wettbewerb einlud. Jeder der Geladenen sollte ein einheitliches Preisgeld erhalten, der Gewinner mit der Ausführung des Denkmals betraut werden. Ziel war es, ein eigenständiges, monumentales Denkmal zu schaffen, welches den Genius des zu ehrenden Dichterfürsten allegorisch darstellt, nicht jedoch eine weitere kostümierte bronzene Kleiderpuppe in die Reihe der bereits vorhandenen einreiht.

In den Räumen der Kgl. Kunstakademie in Berlin beratschlagten innerhalb zweier Tagessitzungen der Gießer, Künstler und Direktor der Münchner Kgl. Kunstakademie Ferdinand von Miller (München), der Tierbildhauer August Gaul (Berlin), der deutschstämmige Bildhauer Karl Bitter (New York), der Architekt Frederick A. Ohmann (Wien) und Harry Rubens über die Entwürfe von Adolph Bermann (München), Hermann Hahn (München), Anton Hanak (Wien), Hugo Lederer (Berlin), Hubert Netzer (München), Othmar Schimkowitz (Wien), Georg Wrba (Dresden), Albert Jaegers (Suffern, N.Y.) und Hans Schuler (Baltimore, Md.). Nach zähen Verhandlungen, dann aber doch einstimmig, entschied sich die Jury für den Entwurf von Hermann Hahn.

Um auch die Öffentlichkeit in Chicago teilhaben zu lassen, organisierten die Initiatoren eine Ausstellung sämtlicher Modelle im Art Institute of Chicago Anfang des Jahres 1911. Das Auswahlverfahren wurde als eines der sorgfältigsten und wohlbedachtetsten in der Presse gelobt, ebenso dessen Ausgang. Geplant war desweiteren eine Rundreise der Modelle durch die wichtigsten Städte der USA; so überzeugt waren die Initiatoren von ihremVorhaben, dass sie die Realisierung der restlichen sieben Entwürfe anstrebten. Der Ausbruch des Krieges verhinderte dieses Vorhaben.

Zur Ausführung bestimmt wurde ein Denkmalsentwurf, der sich von bisherigen Personaldenkmalen in Deutschland eklatant abhob. Und man möchte formulieren: für einen Standort in Deutschland nicht statthaft war; aus deutscher Sicht für Übersee jedoch als Formexperiment durchaus seine Berechtigung hatte.