0,93 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

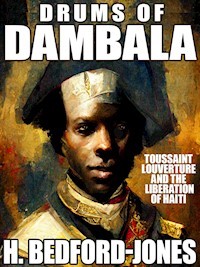

This fine historical novel by adventure writer Henry Bedford-Jones -- the self-styled "King of the Pulps" -- focuses on Toussaint Louverture and the liberation of Haiti. It first appeared in 1932.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 310

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

DRUMS OF DAMBALA, by Henry Bedford-Jones

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

AUTHOR’S NOTE

DRUMS OF DAMBALA,by Henry Bedford-Jones

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2022 by Wildside Press LLC.

Originally published in 1932.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com | blackcatweekly.com

INTRODUCTION

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin Borjigin c. 1155 – c. April 16, 1162 – August 18, 1227), also officially Genghis Emperor, was the founder and first Great Khan and Emperor of the Mongol Empire, which became the largest contiguous empire in history after his death. He came to power by uniting many of the nomadic tribes of Northeast Asia. After founding the Empire and being proclaimed Genghis Khan, he launched the Mongol invasions that conquered most of Eurasia. Campaigns initiated in his lifetime include those against the Qara Khitai, Khwarezmia, and the Western Xia and Jin dynasties, and raids into Medieval Georgia, the Kievan Rus’, and Volga Bulgaria. These campaigns were often accompanied by large-scale massacres of the civilian populations, especially in the Khwarazmian- and Western Xia-controlled lands. Because of this brutality, which left millions dead, he is considered by many to have been a brutal ruler. By the end of his life, the Mongol Empire occupied a substantial portion of Central Asia and China. Due to his exceptional military successes, Genghis Khan is often considered to be the greatest conqueror of all time.

Ghenghis Khan seems a natural subject for author Henry James O’Brien Bedford-Jones (1887-1949). Bedford-Jones was a Canadian-born historical, adventure, fantasy, science fiction, crime, and Western writer who became a naturalized United States citizen in 1908. After being encouraged to try writing by his friend, writer William Wallace Cook, Bedford-Jones began writing dime novels and pulp magazine stories. He became an enormously prolific writer; the pulp editor Harold Hersey once recalled meeting Bedford-Jones in Paris, where he was working on two novels simultaneously, each story on its own separate typewriter.

Bedford-Jones cited Alexandre Dumas as his main influence, and even wrote a sequel to Dumas’ The Three Musketeers, D’Artagnan (1928). All told, he wrote nearly 200 novels, 400 novelettes, and 800 short stories, earning the nickname “King of the Pulps”.

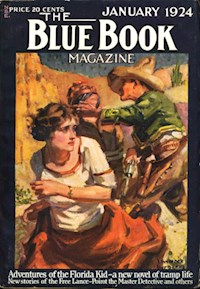

His works appeared in all the leading pulp magazines of the day, but his main publisher was Blue Book magazine. Notable work also appeared in Adventure, All-Story Weekly, Argosy, Short Stories, Top-Notch Magazine, The Magic Carpet/Oriental Stories, Golden Fleece, Ace-High Magazine, People’s Story Magazine, Hutchinson’s Adventure-Story Magazine, Detective Fiction Weekly, Western Story Magazine, and Weird Tales—among many, many others.

Bedford-Jones wrote numerous works of historical fiction dealing with several different eras, including Ancient Rome, the Viking era, seventeenth century France and Canada during the “New France” era. Bedford-Jones produced several fantasy novels revolving around Lost Worlds, including The Temple of the Ten (1921, with W. C. Robertson).

In addition to writing fiction, Bedford-Jones also worked as a journalist for the Boston Globe, and wrote poetry. He counted Erle Stanley Gardner and Vincent Starrett among his friends.

—John Betancourt

CHAPTER 1

LE SERPENT’S PROPHECY

In the early summer of the year 1801, an American brig was standing into the harbor of Cap François, more generally known as Le Cap. Behind her lay Tortuga, the isle of the buccaneers; around and ahead, as she forged in under the great height of Morne Rouge, lay the golden Hispaniola of song and story, whose old native name of Haiti was coming more into local usage.

Before the brig now opened out the marvelous vista of the city, rimmed about by mountains towering up black and green, with still other mountains behind lifting into the clouds. Burned to the ground only nine years previously, and literally drenched in blood, the old city had risen from its ashes in new glory.

On the quarterdeck of the brig stood her sole passenger, while bluff Captain Michaelson pointed out to him the various points of interest showing in the city ahead—the governor’s palace, the theatre, the shipping so thickly lining the quays, the temple of freedom in its little grove. The passenger listened with imperturbable air. He was dark, less than thirty years of age at a guess, and stood a full six feet. Heavy brows shaded heavy-lidded eyes; the lines ran strongly from brow to wide and firm lips, with finely carved nostrils above. When he smiled, merry lights danced in his blue eyes; for beneath those shaggy black brows, his eyes were blue, a light and sparkling blue. The contrast was severe and startling. It attracted attention on the instant. The high-boned features seemed at first glance intolerant, almost arrogant; but upon study of the man one divined how astonishingly great was his self-mastery, his restraint.

He ran his eye over the shipping in the harbor ahead, then broke in upon the captain’s discourse to point out a barge approaching them, a large craft of a dozen oars, carrying a number of soldiers.

“Port officers?” he asked laconically.

“Worse, Master O’Donnell. I remember now, I forgot to salute their cursed French flag in passing the forts.” The master shouted hasty orders at the mate and men, then caught the arm of O’Donnell. “One thing, sir! No talk of negroes or niggers; the word is offensive. These men are blacks, and very proud of it. They wish to be called blacks, as distinct from——”

“Thank you, sir,” and O’Donnell nodded quietly. “I fancy I’ll be able to handle them all right. What’s the matter?”

An exclamation broke from the skipper. In the stern of the approaching barge sat two resplendent officers wearing much gold lace, huge epaulets, and the enormous curved sabres which Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign had brought into fashion in the armies of France.

“You see the big chap on the larboard side? Has but one eye. That is Moyse himself; General Moyse, nephew of Toussaint Louverture. The most perfect devil unhung, a butcher, a very fiend incarnate! He’s capable of anything.”

“We’ll have no trouble,” said O’Donnell calmly. “Leave the talking to me.”

The skipper shrugged, with a hopeless air. The brig came into the wind with flapping canvas, and her gangway was rigged. The barge drew in alongside. The two officers mounted to her deck and strutted aft. The port captain and health officer was a small, alert black, dwarfed by the brawny general beside him, whose features beneath his large cockaded hat wore an expression of scowling ferocity, not lessened by the one empty, hideous eye-socket.

“You, captain!” broke out Moyse angrily, in the Creole patois of the island. “Do you know, citizen, that you passed the forts without a salute? Your American flag was not dipped to the glorious tricolor of France! You and your ship are under arrest——”

“One moment, citizen general,” intervened O’Donnell, using the same patois with surprising fluency. “I will do the answering here.”

Moyse surveyed him. “And who are you?”

“An American. My name is Paul O’Donnell.” As he spoke, O’Donnell produced a folded paper and opened it. “Who may you be, and what is your authority, citizen!”

“I?” Moyse drew himself up. “Moyse! General of the army of San Domingo, captain general of this district, nephew of our governor Toussaint Louverture!”

“Whose signature you doubtless know,” said O’Donnell, holding out the paper.

The general stared at it. He could not read, but he knew well that sprawling signature. He reached out to take the letter; O’Donnell calmly folded and pocketed it.

“This is not for you. It is for General Cristophe, who I believe is in command here at Le Cap.”

“He is my subordinate!” declared Moyse angrily. “I am captain general over the entire north district, do you understand? It’s nothing to me if you carry a letter from that old uncle of mine. You and your ship are under arrest, the cargo is confiscated—”

O’Donnell took a step forward. He tapped the gold-laced chest of the general with its tinkling medals, and stared into the one flaming, savage eye. His calm assurance checked the ire of the brawny black.

“Now, listen,” he said quietly. “Stop rattling your tongue, like a monkey shaking stones in a calabash; look at me, listen to me. You are not giving orders here. I am! Here is a letter from Toussaint Louverture, ordering that every courtesy and assistance be given me by all his officers and agents. The stores, munitions and other cargo of this ship are his property. Interfere with them or with me, and you will certainly suffer. And what is more—look at me! Now do you understand, citizen general?”

That an American should speak the patois so fluently was astonishing enough; but there was more. The scarred countenance of Moyse underwent a curious change as he met the direct, staring gaze of O’Donnell. He made a swift, furtive gesture which the American understood perfectly.

“You need not look at me like that,” he said sulkily, in a very altered tone. “I have not harmed you. I have only come aboard to welcome you to Le Cap. I will go ashore and tell Citizen Cristophe of your arrival. The port captain will take care of your ship.”

While bluff Captain Michaelson gaped in utter incredulity, Moyse turned and went over the side again into his barge, which departed at once. The little port captain, staring at O’Donnell with bulging eyes, swallowed hard and then made a brisk salute.

“All right, sar,” he said in English. “No more trouble. I take care of you, sar. Let me have the ship’s papers, cap’n. I pilot her in.”

He went to the wheel, accompanied by the mate, who gave sharp orders; the brig picked up way again. The astounded skipper plucked at O’Donnell’s sleeve.

“What the devil does it all mean? How did you settle him so quick, eh?”

O’Donnell’s rather harsh features relaxed. He glanced at the port captain with a whimsical smile, and the black grinned happily at him, in obvious relief.

“Partly the name of Louverture,” said O’Donnell, “and partly because they’re afraid of the evil eye. Better get your ship’s papers for that chap, cap’n. You’ll find all clear now.”

Not comprehending in the least, the seaman shrugged and turned away. O’Donnell looked over the rail at the retiring barge, then past the other shipping to the long quays and the paved plaisance or harbor walk where black soldiers loafed in the sunlight. He chuckled softly to himself as he took a cigar from his pocket and bit at it.

Blue eyes and black brows did not necessarily mean anything, but when properly used they meant everything. This peculiar mannerism had more than once been of the utmost use to O’Donnell. If, when he opened his eyes wide and stared at them, black folk credited him with having the evil eye, he was not slow to take advantage of the fact. The twist of character, or personality, causing this singular belief was past his explanation, but the effect was obvious enough.

Presently the brig was moored at the quay. The customs officers trooped aboard, and the mulatto heading them could read well enough. The ship’s papers, the name of Toussaint Louverture, quickly banished all formalities; throughout Haiti this name was a magic talisman. Toussaint was nominally governor in the name of the French Republic, but the French commissioners were absolutely powerless in the land, every iota of authority was centered in him and in his lieutenants, and it was rumored that he planned to become a king in name as well as in fact.

During the past nine years, Toussaint had risen from the position of a slave to that of a ruler more despotic than Bonaparte himself. His mere word was law, his power was unlimited, the military government he had instituted was absolute. His name was feared terribly, even by his savage lieutenants, themselves feared by all other men. During these years Toussaint had emerged from a literal sea of blood. Barbaric warfare, slaughter, flame and pitiless massacre had swept this entire island from end to end; yet in emerging from these years, Toussaint bore no stain of blood, no taint of cruelty. His justice was feared, but it was justice.

Arranging to send later for his luggage, O’Donnell left the brig and sauntered along the quays. He was in no haste to reach his destination, and wanted first to get a glimpse of the busy city, so totally different from the old city of nine years back that had been swept out of existence in four days of blood and fire. On every side were vast bustle and confusion. Ships were loading and discharging, lighters were going out to larger craft, carts were rumbling on the cobbles, and the astonishing thing was that only soldiers loafed about. Idleness was a crime under the regime of Toussaint, so far as the blacks were concerned.

Coming to the Grand Cafe, the center of social and even business life on the quays, O’Donnell turned into the city, passing through the streets to the central Place d’Armes. He found wide streets, magnificent houses, tokens of the greatest prosperity on every hand. The governor’s palace, with its magnificent appointments, the imposing theatre billing the latest plays from Paris, the busy shops, all spoke eloquently of the vast wealth being produced by the reborn commerce of the island. White planters, whom Toussaint had brought back from exile to their former estates, rode through the streets on horseback, or in extremely ornate carriages with their ladies. Certain of these ladies also rode on horseback, wearing male garments and riding astride—a thing unheard of in America but not unusual in the islands and even in Paris, where Josephine and her circle had introduced the custom.

Gazing around him with frank interest, O’Donnell finally headed back towards the quays. Out across the busy harbor rose the gigantic headland dominating the western end of the bay; past the gap in the girdling hills lay the great Plaine du Nord, once the home of the richest plantations in all the new world. Thinking of these things, O’Donnell mechanically turned aside to avoid an approaching rider, only to find the horse abruptly checked beside him. A silvery voice, penetrating, sweet, of remarkable quality, greeted him in French.

“So you have come back to our island, citizen?”

O’Donnell turned, looked up, removed his hat.

The woman in the saddle above, smiling down at him, was of a startling and vivid beauty; she was not above twenty-four or five. Raven hair, superb dark eyes filled with intelligence and fire, features delicately molded yet firm and assured, met his gaze. Her man’s attire was all of green and gold, very rich, and a black groom in the same livery rode at her stirrup. Some planter’s wife or daughter, no doubt; certainly a very beautiful woman, though too hard about the mouth to please O’Donnell.

“Madame, I fear there is some mistake,” he said, with a bow. “I am a stranger here, and to my great regret cannot claim acquaintance either with Le Cap or with its loveliness so suddenly personified before me.”

A laugh curved her lips, but he noted that it did not touch her eyes. On second glance, they too carried a certain peculiar hardness.

“Indeed!” she returned in surprise. “Then you are not M. Borie?”

O’Donnell smiled, and somehow kept the heart-leap from his face.

“I am an American, madame, by name O’Donnell, a commercial agent by profession.”

“So?” She regarded him for an instant. “You are the first commercial agent I ever saw who looked like an officer and a gentleman.”

“In America, madame, all men are gentlemen, and two-thirds of them are officers of something or other.”

She disregarded his whimsical response, turned her head with an impatient word to her groom, brought her riding crop smartly down, and was gone with a scramble of hooves. Looking after her, O’Donnell’s gaze narrowed. Then he swung his cloak about his shoulders, pulled his hat over his eyes, and headed again for the quays.

“What a devilish stroke of luck! That was no coincidence. She knew something, she had meaning in her words. Decidedly, I’ve made a bad beginning!”

So thinking, he drew aside against a shop-front to let a blind, crippled old black go past. He had seen beggars enough around the cathedral in the Place d’Armes, but this creature was different. Bent half double, hobbling along with a stick outstretched before him, the scarred black thing was horrible to see. All his upper face was a repulsive scar. His left arm was twisted as though by fire, though he still used the hand. Among the rags half covering his body, O’Donnell discerned a number of native charms, showing that the man was some vaudou worshipper from the hills, perhaps a priest of the cult. This seemed the more probable because the black folk retreated hurriedly from him, so that in the crowded street he walked alone.

Within arm’s length of O’Donnell, he halted and turned his sightless face to the American.

“Speak!” he said in Creole, his voice very low. “I feel you there. I can smell the blood that drips on the stones behind you. Fool! Because Le Serpent is blind, does he know nothing? Does not Dambala, the snake god, whisper to him of all that passes? I know why you have come here. Speak to me.”

O’Donnell glanced around and saw no one within hearing, though frightened faces were turned toward them.

“What shall I say?” he rejoined in the patois. “Are you a friend or enemy?”

Le Serpent cackled in hideous mirth. “You ask me that! If I were an enemy, you would not be so strong and handsome, my fine man. I know why you are here; gold and blood surround you as you walk. Gold and blood! And you know not what will come of it, but Le Serpent knows. The snake god has whispered to me. The flames will glow red against the sky, and men will die, and the woman in green and gold will throw back her head and laugh when you are stretched on the wheel for breaking.”

“What’s that?” O’Donnell started. “You know that woman?”

The blind man’s stick reached out and touched his shoulder, pressing hard against him for a moment, then fell again.

“Do I know Citizeness Rigaud, la belle Hermione? Yes. And I know you, my fine man! Well, your errand will come to nothing unless you find the man Mirliton. Remember the name, remember well the name! You have a false errand and a real errand, and I know what they are. This is the second time within two years that I have spoken with a Borie.”

Le Serpent departed, hobbling away down the street. O’Donnell stared after him, speechless for the moment. He had thought himself dealing with some half-crazed vaudou man from the hills, as he undoubtedly was; but this maimed wretch seemed positively able to read his mind. “A false errand and a real errand”—well, this was true, but not a soul in the world knew it except O’Donnell himself.

Collecting his startled senses, O’Donnell continued his way back to the quays. Gold and blood! Some truth in this also. At least, his ostensible errand here in Haiti was concerned with gold, and one might say his real errand was one of blood. That final sentence, however, was what held O’Donnell spellbound.

The gabbled prediction he dismissed. In his youth he had frequently met these wild folk, devotees of the snake god, the mountain god, or other black deities, and he took small stock in any of their prophecies. He did know, however, that they possessed strange and varied powers. The blind man had certainly sensed him, had named him, might have read his mind by some sort of telepathy. Unless, indeed, the cripple had overheard his brief conversation with the woman in green and gold. That might explain anything—except the final sentence.

“Another Borie!” muttered O’Donnell. “There could be only one other in the world, so this gives me a clue. He’s a friend, certainly; my one chance of success is not to antagonize these mountain blacks. A good augury! Find the man Mirliton, eh? That’s the name of a squash or calabash, I remember. Well, time enough lost! Now for Dupuche.”

Halting a strapping black officer, he inquired his way.

“Dupuche? But yes, citizen,” was the response. “House number ten, Quai Desfarges; straight ahead and to the right at the corner. You cannot—you—you—”

The officer’s eyes widened, became distended; his jaw dropped. Following his gaze, O’Donnell glanced down at his light gray cloak. What brought this look of startled fear into the black face? He could see nothing, except a round spot of red on the left shoulder. He rubbed at it, and it did not come off. Then he remembered suddenly the pressure from the blind man’s stick. Undoubtedly this stick had made the mark.

O’Donnell glanced up to question the officer, but the latter was striding away in hot haste, his big epaulets bobbing up and down. With a shrug, the American went his way.

He knew that he had come into a land of spies, of intrigue, only recently drawn from a chaos of the most frightful warfare and butchery imaginable. If Le Serpent had put this mark on his cloak, it most certainly had a meaning; the blacks might know it, but he would lose time questioning them. Here in Haiti reigned bitter hatred between blacks and mulattoes, but not between blacks and whites. As a general thing, the attitude of the ruling blacks was one of amiable friendliness or indifference toward the whites. They would tell no secrets, though.

“Therefore, I’d best leave the mark alone,” thought O’Donnell. “It may be useful.”

He turned in at a warehouse and residence combined, whose signboard announced the business of Dupuche & Delcasse, Negociants. Ships were unloading along the quay; in and out of the warehouse poured every kind of merchandise from wine to furniture, while plantation carts were rumbling up with loads of sugar and rum, and going away empty. O’Donnell stepped into the dingy office where white and mulatto clerks bent over ledgers, and addressed the nearest of them.

“Is Citizen Dupuche here?”

“He is busy, citizen,” came the brusque response. “When he has finished with the aide-de-camp of General Moyse, he will see you.”

“Indeed!” said the American coolly. “You will kindly inform him that Citizen O’Donnell of Philadelphia is here to see him on direct business of the governor, and that he may send the aide of General Moyse to the devil. Sharp about it, citizen!”

The clerk blinked at him, then departed hastily while the others stared. Evidently the message was delivered literally. A moment after, the door of an inner office was flung open and out strode a mulatto in colonel’s uniform, jingling his sabre and flinging an arrogant and furious look at O’Donnell. After him came Dupuche, rushing forward to grip his visitor’s hand and shake it heartily.

“Citizen O’Donnell at last!” he exclaimed. “I did not know what had become of you. The ship was in, but you were ashore and they knew nothing of you. I have taken the liberty of sending for your things; you’ll stop in my house, as my guest. Come, enter! I am honored by your presence, citizen. From our long correspondence, from our business dealings, I feel that I know you well already. You outside there—admit no one! I am not to be disturbed. In half an hour I shall want a messenger to ride to the habitation d’Héricourt.”

The American found himself ushered into a book-lined office, bare except for chairs and a large table stacked with papers. Dupuche pulled a bell cord, and a black woman appeared at a door leading into the residence.

“Bring wine, cakes, sherbet, whatever Madame may have.”

Studying his host, O’Donnell found the Frenchman to be a man of fifty, rather small of build, with ornate whiskers and much cheap jewelry in evidence. By no means an impressive person at first glance; but those square, hard-jawed features, those shrewd little eyes, told quite another story. Citizen Dupuche, confidential agent of Toussaint Louverture, had not only survived anarchy, massacre, and flame, but was riding the crest of the incredible richness and prosperity that liberty had brought to Haiti.

“Do you wish to talk of business or of personal affairs?” said Dupuche, setting out a box of Havanas.

“The latter first,” rejoined O’Donnell. “I suppose that the matter of the ship’s cargo is now in your hands?”

“All attended to and out of the way. I gathered, from the last letter you sent me, that you have personal affairs here of some importance.”

“Yes. You forwarded me the letter from Toussaint, addressed to General Cristophe——”

Dupuche laughed and waved his hand.

“Let it wait, my friend. Henry Cristophe is a good soul, a great man, and lives like a king; he’ll dine you off gold plate, give you whatever you fancy, and drink you under the table. But you have made an enemy here, and a bad one. A bitter one. A powerful one. Moyse will some day betray his uncle or rebel against him; until that day comes, he is to be placated and feared. He’s unbelievably crafty, also. Dangerous.”

“So you heard how he boarded the brig, eh?”

“And how you sent him back. He’ll not forget, mind.”

O’Donnell shrugged carelessly. The servant appeared with a tray bearing wine and cakes and sweetmeats. When she had gone, Dupuche filled the glasses and, lifting his own, sniffed it with appreciation.

“I have but one toast to offer, citizen—Toussaint Louverture! Not bad, this wine. The Englishmen certainly know wines! General Maitland sent this to Toussaint, after his capitulation, and Toussaint sent it to me, as he never uses wine.”

O’Donnell’s brows lifted in surprise, and the other smiled.

“I see you know little of our governor. No, he drinks only water, eats a little bread or biscuit, a potato or so—that is all. Well, my friend, you’ve been his agent in Philadelphia for the past couple of years, and since most of the accounts have gone through my hands, I know you have been a good agent. Toussaint thinks highly of you.”

“Thank you.” O’Donnell lighted a cigar. “When shall I be able to see him?”

“God knows! In a day, a week, a month. Where he is, no one ever knows. He is presumably at Port au Prince now, but I send all messages to the plantation. They are forwarded.”

“I must see him as soon as possible,” said O’Donnell. “As you know, many of the émigrés from this island live in Philadelphia, and due to my own connections many of them are my friends. While it is true that numbers of the old families have returned here to resume life on their plantations, at the invitation of the governor, others have not done so. Many do not trust him, others believe that anarchy will ensue if he is killed.”

Dupuche shrugged. “Personally, I think the Tiger will ensue,” he said drily. “In other words, Jean Jacques Dessalines; or perhaps Cristophe. I’d prefer to bet on Dessalines. He’s a killer, and these blacks fear killers. If the French return and try to seize the island, anything may happen. But pray resume, citizen! Toussaint is far from dead, thank heaven!”

“You must be well aware,” pursued O’Donnell, “that at the time of the first massacres and revolts nine or ten years ago, many of the planters buried their valuables and fled, glad to escape with their bare lives.”

“And few were lucky enough for that, even,” assented Dupuche with a nod.

“The short of it is that the emigrant members of four families have commissioned me to visit their former plantations and to disinter their valuables,” said the American. “These may or may not be still concealed. I have received explicit instructions, which are in my memory alone, as to finding these hidden belongings. I am hoping to secure permission to this end from Toussaint.”

Dupuche lit a cigar, inspected it critically, and puffed it into a glow.

“I admire your frankness, citizen. Your errand may prove dangerous.”

“You think Toussaint may not give permission?”

“Oh, readily enough! But you must comprehend the situation here. Some of the plantations are in the hands of the original owners, who have returned. Most, however, have been farmed out to officers of the black army. The labor laws are rigidly enforced, the plantations are managed with efficiency; and the result? Wealth. The wealth of Croesus, my friend! The revenues from the rented plantations alone more than cover the entire government expense. The planters have gained incredible riches, and so have others. Why, in the Spanish treasury at Santo Domingo, Toussaint found close to a million gourdes, or dollars, when he took that city. The state is wealthy. The people are wealthy. Luxury is on all sides of us; you have no idea in what mad luxury some of these people, white and black, are living! So much for that.”

He paused, sipped at his wine, and then lowered his voice as he proceeded.

“Death, too, is on all sides. Toussaint is all-powerful, but cannot be everywhere, and without him there is no restraint. He refused to let the English make him king here, because he believes in France and in Bonaparte. He refuses to credit my warnings. I know that Bonaparte means to destroy him and retake Haiti. There are French spies and agents among us. There are English spies and agents. The mulattoes, who hate the blacks, have their spies and agents. So have the Spanish.

“Your arrival, your very errand here, is probably known far and wide already. Certain of the blacks hate Toussaint because he is just and merciful, and makes them work, and favors the whites, as they think. At the head of these dissenters is his own nephew, Moyse, who would gladly murder him—and has tried to do so. Well, then! What passes in the mountains?”

Dupuche puffed his cigar alight. “In the mountains are the maroons, escaped slaves. They are independent; Toussaint has made them submit, but has not conquered them. What passes in the far gorges, on the roads, among the plantations even of the Plaine du Nord? Death! Death passes everywhere, I tell you. My friend, this is a land of death!” Agitation shook the man suddenly, as he leaned forward. “Give up your errand here and go safely home. I warn you! Here is a land of brave men, of damnable intrigue, of savage ignorance, of death behind a glittering smile. Go back!”

“No.”

O’Donnell uttered just the one word. The Frenchman looked into his eyes for a moment, drew a deep breath, and with a gesture of helplessness relaxed in his chair.

“Then that is settled. I shall see that you reach our governor as soon as possible. By the way, what plantations do you wish to visit and search?”

“That of Aussenac. That of Langlade. That of Dartigues. That of Borie.”

At this last word, Dupuche changed countenance.

“Monsieur! I—I mean, citizen! That was the richest plantation on the whole island, in the old days. It is the richest today. It was bought from the Borie family by Citizen St. Leger some time since.”

“And who is St. Leger? A Creole?” asked O’Donnell curiously.

“No. A man of color, a mulatto. He is supposed to be in secret the head of all the mulatto faction, but no one knows certainly. He was educated in France. He is intelligent, able, unscrupulous.”

“You appear unduly disturbed,” said O’Donnell drily. “You say that he bought the plantation from the Borie family?”

“From one of the heirs, yes. Old Colonel Borie was killed in the first outbreak. Two years ago, his son Alexandre returned from exile, sold the plantation to St. Leger, and then vanished very suddenly. Some say he was murdered; I do not know. He has a brother somewhere in America, I believe. St. Leger produced the proper documents and is now the resident owner. The plantation has given him wealth, but beyond wealth lies power, and dark things are said of him. He is a man of moods. Let him take a fancy to you—voilà! The world is yours. If not, he may have you shot from ambush. Sometimes I am tempted to think he is merely an honest sort of fellow trying to keep his head above water. He’ll not let you remove anything.”

“He will at the order of Toussaint,” said O’Donnell. “And I have the authorization of this surviving Borie heir to get the family treasures, hidden at the plantation.”

“You were wiser not to press the matter,” warned Dupuche uneasily. “Enemies of St. Leger have a way of disappearing.”

“You think he murdered Alexandre Borie after buying the plantation?”

Dupuche frowned. “No. I tell you I think he’s honest, after a queer fashion all his own! But he may have done so. And he is a friend of Moyse. He also acts for British interests here. Suppose you let this matter drop for the present—”

“No,” said the American, with the same finality as before, and the other threw out his hands. “Do you, by any chance, know a lady named Rigaud?”

“God forbid!” answered Dupuche, and the color ebbed from his cheeks as he peered at O’Donnell. “Do you?”

“I encountered her today. What do you know of her? I did not care for her looks, myself.”

The other shrugged.

“She is French—married Rigaud in Paris three years ago. He was a proud man, of the best blood in France. They came here to the old Rigaud plantation and he died shortly after. She manages it now. She has varied interests; chiefly, I believe, political. She is friendly with St. Leger. She mixes freely with the blacks and mulattoes. She is a secret agent here for Bonaparte; since we know this, we leave her alone and watch her. So far, so good. But things—well, things are said of her, difficult to repeat between gentlemen. The blacks declare she is a vampire. I have heard that she has pried into vaudou affairs. There’s something about her—you can feel it but you can’t see it, can’t determine it!”

“Exactly the impression she gave me,” affirmed O’Donnell, and laughed a little. “She mistook me for someone else. For one of the Borie family, I think.”

Dupuche shook his head, and chewed on his cigar for a moment.

“My friend, I ask no questions,” he said slowly. “There are women for whom no words have been invented. She is one of them. For nine years, cruelty and blood-lust have run riot in this land. I have seen men and women murdered by the score, tortured, mutilated, done to death by men more savage than beasts. Yet there is something inhuman about this woman that terrifies me. If she or St. Leger were at all interested in your arrival here, you may be sure they learned of it long before you came. There are spies in Philadelphia as well as in Le Cap.”

O’Donnell’s dark, powerful features seemed to tighten imperceptibly.

“So? I understand,” he said, and then broke into a smile. “Well, that’s all of my personal business here, my dear Dupuche. If you’ll be good enough to write Toussaint whatever you see fit, and arrange for me to see him, I’ll be glad. In the meantime——”

“Present your letter to Cristophe, who will immediately make you free of Haiti, thrust gold into your pocket, and present you with a handsome horse,” said Dupuche ironically. “He will make you feel at home, certainly. Tell him I said he’s an honest rascal, and he’ll love you. He regards Toussaint as a brother, absorbs flattery like a sponge, and hates Moyse as the devil hates holy water.”

“Good! But I must not impose on your hospitality——”

“My house is your home while you are here, my friend,” said Dupuche with grave courtesy. “A room is prepared for you. Take your meals with us, unless you go invited elsewhere. Be free, come and go as you like. You are one of the family. We’ll talk again, eh?”

So O’Donnell went to his room. He had learned a good deal about Haiti—and wondered just how much Haiti had learned about him.

CHAPTER 2

FRIENDS AND ENEMIES

General Henry Cristophe did not shove any gold into O’Donnell’s pockets. However, he informed him that an excellent horse would arrive as a present for him; and then, relaxing comfortably, he puffed his long clay pipe alight, unbuttoned his high gold-laced collar, and asked O’Donnell to tell him about America.