0,91 €

Mehr erfahren.

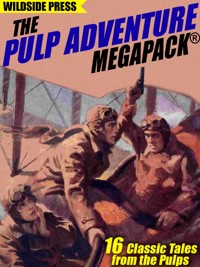

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

When you think of the pulp magazines that flourished in the first half of the 20th century, it’s hard not to think of adventure—the term “pulp fiction” these days has come to mean slam-bang action. That’s what this volume of our MEGAPACK® is here to celebrate: great adventure stories.

Included are:

HE SWALLOWS GOLD, by H. Bedford-Jones

PLANE JANE by Frederick C. Davis

ARCTIC ANGELS, by A. DeHerries Smith

THE TAKING OF CLOUDY McGEE, by W.C. Tuttle

ESPECIALLY DANCE HALL WOMEN by Alma and Paul Ellerbe

ISLAND HONOR, by Murray Leinster

NERVE ENOUGH, by Richard Howells Watkins

BY ORDER OF BUCK BRADY, by W.C. Tuttle

CODE, by L. Paul

SALVAGE, by Roy Norton

THE LUCKY LITTLE STIFF, by H.P.S. Greene

WHEN EVERYBODY KNEW, by Raymond S. Spears

THE SOUL OF HENRY JONES, by Ray Cummings

THEN LUCK CAME IN, by Andrew A. Caffrey

TOO MUCH PROGRESS FOR PIPEROCK, by W.C. Tuttle

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 460

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION

ABOUT THE MEGAPACK® SERIES

HE SWALLOWS GOLD, by H. Bedford-Jones

PLANE JANE by Frederick C. Davis

ARCTIC ANGELS, by A. DeHerries Smith

THE TAKING OF CLOUDY McGEE, by W.C. Tuttle

ESPECIALLY DANCE HALL WOMEN by Alma and Paul Ellerbe

ISLAND HONOR, by Murray Leinster

NERVE ENOUGH, by Richard Howells Watkins

BY ORDER OF BUCK BRADY, by W.C. Tuttle

CODE, by L. Paul

SALVAGE, by Roy Norton

THE LUCKY LITTLE STIFF, by H.P.S. Greene

WHEN EVERYBODY KNEW, by Raymond S. Spears

THE SOUL OF HENRY JONES, by Ray Cummings

THEN LUCK CAME IN, by Andrew A. Caffrey

TOO MUCH PROGRESS FOR PIPEROCK, by W.C. Tuttle

INTO THE BLUE, by F. Britten Austin

ABOUT THE MEGAPACK® SERIES

Wildside Press’s MEGAPACK® Ebook Series

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

The Pulp Adventure MEGAPACK® is copyright © 2024 by Wildside Press, LLC.

The MEGAPACK® ebook series name is a registered trademarkof Wildside Press, LLC.

All rights reserved.

*

“He Swallows Gold,” by H. Bedford-Jones, was originally published in Argosy and Railroad Man’s Magazine, May 3, 1919.

“Plane Jane,”by Frederick C. Davis, was originally published in Adventure, Aug. 1928.

“Arctic Angels,” by A. DeHerries Smith, was originally published in Adventure, Nov. 15, 1928.

“The Taking of Cloudy McGee,” by W. C. Tuttle, was originally published in Short Stories, Feb. 10, 1926.

“Especially Dance Hall Women,” by Alma and Paul Ellerbe, was originally published in Adventure, July 1, 1928.

“Island Honor,” by Murray Leinster, was originally published in Short Stories, Feb. 10, 1926

“Nerve Enough,” by Richard Howells Watkins, was originally published in Adventure, Dec. 30, 1925.

“By Order of Buck Brady,” by W.C. Tuttle, was originally published in Adventure, July 1, 1928.

“Code,” by L. Paul, was originally published in Adventure, Nov. 15, 1927.

“Salvage,” by Roy Norton, was originally published in The Popular Magazine, Feb. 4, 1928.

“The Lucky Little Stiff,” by H.P.S. Greene, was originally published in Adventure, Oct. 1, 1927.

“When Everybody Knew,” by Raymond S. Spears, was originally published in Adventure, July 15, 1928.

“Then Luck Came In,” by Andrew A. Caffrey, was originally published in Adventure, Nov. 15, 1928.

Too Much Progress For Piperock,” by W. C. Tuttle, was originally published in Adventure, April 30, 1922.

“Into The Blue,” by F. Britten Austin, was originally published in The Blue Book Magazine, March 1924.

INTRODUCTION

When you think of the pulp magazines that flourished in the first half of the 20th century, it’s hard not to think of adventure—the term “pulp fiction” these days has come to mean slam-bang action. That’s what this volume of our MEGAPACK® is here to celebrate: great adventure stories.

Although the pulps published every type of fiction imaginable, from romance to mystery to science fiction to westerns to horror, I have focused this volume on tales of heroes—both small and larger-than-life—with a special emphasis on stories from Adventure magazine. It’s an eclectic mix, with westerns, sea stories, air stories (pilots were heroes in the early days of aviation, especially during and after World War I), mysteries, and more. It surprises many who aren’t familiar with pulps that the quality of fiction they published—especially in the leading magazines, whose circulations often topped a million copies per issue—was quite high. They paid substantial money for the stories they published, and successful writers earned good livings. Some transitioned to movies; others moved on to the “slick” magazines (which paid substantially more). But many, especially those who enjoyed working in specific genres like mystery and science fiction, were content to write just for the pulps.

Among the notable names in this volume are W.C. Tuttle (who was quite prolific and one of the top western authors of the era); H. Bedford-Jones (the self-proclaimed “king of the pulps,” who published millions of words of fiction every year and became a favorite of many for his tales of adventure, often in exotic lands); Murray Leinster (still remembered for his classic science fiction—though he wrote in every genre, from romance to mystery to mainstream); and Ray Cummings (who wrote classic science fiction before the term was invented, and went on to have a decades-long career in the science fiction magazines and comic books). Also check out Raymond S. Spears, who is one of my favorite pulp writers—I don’t know much about him, but he never fails to entertain.

Enjoy!

—John Betancourt

Publisher, Wildside Press

wildsidepress.com

ABOUT THE MEGAPACK® SERIES

Over the last decade, our MEGAPACK® ebook series has grown to be our most popular endeavor. (Maybe it helps that we sometimes offer them as premiums to our mailing list!) One question we keep getting asked is, “Who’s the editor?”

The MEGAPACK® ebook series (except where specifically credited) are a group effort. Everyone at Wildside works on them. This includes John Betancourt (me), Carla Coupe, Steve Coupe, Shawn Garrett, Helen McGee, Bonner Menking, Sam Cooper, Helen McGee and many of Wildside’s authors…who often suggest stories to include (and not just their own!)

RECOMMEND A FAVORITE STORY?

Do you know a great classic science fiction story, or have a favorite author whom you believe is perfect for the MEGAPACK® ebook series? We’d love your suggestions! You can email the publisher at [email protected]. Note: we only consider stories that have already been professionally published. This is not a market for new works.

TYPOS

Unfortunately, as hard as we try, a few typos do slip through. We update our ebooks periodically, so make sure you have the current version (or download a fresh copy if it’s been sitting in your ebook reader for months.) It may have already been updated.

If you spot a new typo, please let us know. We’ll fix it for everyone. You can email the publisher at [email protected] or contact us through the Wildside Press web site.

HE SWALLOWS GOLD,by H. Bedford-Jones

Originally published in Argosy and Railroad Man’s Magazine, May 3, 1919.

I

“We, all of us,” said Huber Davis reflectively, “like to show off how we do things; we like to tell people about our methods; we like to exposit our particular way of managing affairs. Each of us thinks he is a little tin god in that respect, Carefrew. That’s the way of a white man. A Chinaman, however, is just the opposite. He does not want to show his methods. He does things in a damned mysterious way—and he never tells.”

Carefrew sucked at his cigarette and eyed his brother-in-law with a sneer beneath his eyelids. Only a few hours previously Carefrew had landed from the coasting steamer, very glad indeed to get out of Batavia and parts adjacent with a whole skin. His wife was coming later, after she had straightened up his affairs, and he would then hop aboard the Royal Mail liner with her, and voyage on to Colombo and Europe. Ruth Carefrew, however, knew little about the deal which had sent Carefrew himself up to Sabang in a hurry.

“You seem to know a lot about Chinese ways,” said Carefrew.

“I ought to,” admitted Huber Davis placidly. “I’ve been dealing with ’em here for the past ten years, and I’ve built up a whale of a business with their help. You, on the other hand, got into a whale of a mess through swindling the innocent Oriental—”

“Oh, cut out the abuse!” broke in Carefrew nastily. “What are you driving at with your drivel about Chinese methods? I suppose you’re insinuating that they’ll try to get after me away up here at Sabang?”

“More than likely,” assented Huber Davis. “They have fairly close connections, what with business tongs and the Heaven-and-Earth Society, which has a lodge here. They’ll know that the clever chap who carried out that swindling game in Singapore, and then managed to put it over the second time in Batavia, is named Reginald Carefrew. They’ll have relatives in both places; probably you ruined a good many of their relatives—”

“Look here!” snapped Carefrew nastily. “Let me impress on you that there was no swindle! The Chinese love to gamble, and I gave ’em a run for their money—that’s all.”

Huber Davis eyed his brother-in-law with a trace of cynicism in his wide-eyed, poised features.

“Never mind lying about it, Reggy,” he said coolly. “You’ll be here until the next boat to Colombo, which is five days. In those five days you take my advice and stick close to this house; you’ll be absolutely safe here. I’m not helping and protecting you, mind, because I love you—it’s for Ruth’s sake. Somehow, Ruth would be sorry if you got bumped off. No one else would be sorry that I know of, but Ruth’s my sister, and I’d like to oblige her. I don’t order you to stay here, mind that! It’s merely advice.”

Under this lash of cool, unimpassioned truths Carefrew reddened and then paled again. He did not display any resentment, however. He was a little afraid of Huber Davis.

“You’re away off color,” he said carelessly. “Think I’m going to be a prisoner here? No. Besides, I honestly think there’s no danger, in spite of your apprehension. The yellow boys have nothing to be revengeful over, you see.”

“Oh,” said Huber Davis mildly. “I understood that several had committed suicide back in Batavia. That makes you their murderer, according to the old beliefs.”

Carefrew laughed; his laugh was not very good to hear, either.

“Bosh!” he exclaimed. “Those old superstitions are discarded in these days of New China. You’ll be saying next that the ghosts of the dead will haunt me!”

“They ought to,” retorted Huber Davis. “So you think the old beliefs are gone, do you? Well, we’re not in China, my excellent Reggy. We’re in Sabang, and the Straits Chinese have a way of clinging to the beliefs of their ancestors. You stick close to the house.”

“You go to the devil!” snapped Carefrew.

Huber Davis merely shrugged his shoulders, as though he had received all the consideration which he had expected.

“Li Mow Gee,” he observed, “is the biggest trader in these parts, and I know he has a raft of relatives back your way. I’d avoid his store.”

Carefrew, uttering an impatient oath, got up and left the veranda.

Huber Davis glanced after his brother-in-law, a sleepy, cynical laziness in his gaze. One gathered that he would not care a whit how soon Carefrew died, except possibly that his sister Ruth still loved Carefrew—a little. And except, of course, that the man was his own brother-in-law, and at the ends of the earth a white man upholds certain ideas about caste and the duty of white to white, and so forth.

II

Singapore is called the gateway of the Far East, but the real portal is the free-trade island harbor of Sabang, at the northern end of Sumatra.

At Sabang even the mail-steamers stop, coming and going. From England and India, coal is dumped at Sabang; the wharves and floating docks are many and busy; the cables extend from Sabang to all parts of the globe.

From the harbor heads runs brilliant blue water up to the brilliant green shores, and under the hill is snugly nestled a city whose Chinese streets convey a dull-red impression. Here, as elsewhere, the Chinese are the ganglia of trade and activity. The Dutch government likes them and profits by them, and they profit likewise.

One of the narrow Chinese streets turns sharply, almost at right angles, and is called the Street of the Heavenly Elbow for this reason. At the outside corner of the elbow is a door and shop sign, opening upon a narrow room little wider than the door; but behind this is another room, widening as one goes farther from the elbow, and behind this yet another room which broadens into a suite of apartments.

Such was the shop of Li Mow Gee. As is well known, Li is one of the Four Hundred surnames, and betokens that its owner is at least of good family, also widely connected. Li Mow Gee was both; to boot, he was very rich, considerably dissipated, and his private affairs were exactly like his shop—they began at a small and obscure point, which was himself, and they widened and widened beyond the ken of passersby until they comprised an extent which would have been incredible to any chance beholder. But Li Mow Gee saw to it that there were no chance beholders of his private affairs or shop either.

Li Mow Gee was not the type of inscrutable, omnipotent gambler who somehow manages to control fate and carry out the purposes of destiny, such as appear to be many of his race. He prided himself upon being a “son of T’ang”—that is, a man of the old southern empire whose ancestry was quite clear and unblemished through about nine centuries.

He was a slant-eyed, yellow-skinned, wrinkled little man of fifty. He had a bad digestion and an irritable temper, he was much given to rice-wine and wives, and he possessed an uncanny knowledge of the code of Confucius, by which he ruled his life—sometimes.

Upon the day after Reginald Carefrew arrived in Sabang the estimable Li Mow Gee sat in his private back room, which was hung with Chien Lung paintings, whose subjects would have scandalized Sodom and Gomorrah. Li Mow Gee sucked a three-foot pipe of bamboo and steel, and watched a kettle of water bubbling over a charcoal brazier. At the proper moment he took a pewter insert from its stand, slipped it into its niche inside the kettle, and watched the water boil until the pewter vessel was well heated. Then he poured hot rice-wine into the thimble-cup of porcelain at his elbow, sipped it with satisfaction, and clapped his hands four times.

One of the numerous doors of the room opened to admit a spectacled old man who was a junior partner of Li Mow Gee in business, but who was also Venerable Master of the local lodge of the Heaven-and-Earth Society. As etiquette demanded, the junior partner removed his spectacles and stood blinking, being blind as a bat without them.

“As you are aware, worshipful Chang,” said Li Mow Gee after some preliminary discourse, “my father’s younger brother has become an ancient.”

Mr. Chang bowed respectfully. A son of T’ang never says of his family that they are dead. But Mr. Chang had heard that Li Mow Gee’s father’s younger brother had committed suicide, with the intent of sending his avenging ghost after one Reginald Carefrew.

“You are also aware,” pursued Li Mow Gee, refilling the steel bowl of his pipe, “that the brother-in-law of my friend Huber Davis has arrived in Sabang for a short visit. As a man of learning, you will comprehend that I have certain duties to perform.”

Mr. Chang blinked, and promptly took his cue.

“You doubtless recall certain canons of the law which bear upon the situation,” he squeaked blandly. “It would give me infinite pleasure to hear them from your lips.”

Li Mow Gee had been waiting for this. He exhaled a thin cloud of smoke, and quoted from his exact memory of the writings of the Confucian canon:

“With the slayer of his father, a man may not live under the same sky; against the slayer of his brother, a man must never have to go home to seek a weapon; with the slayer of his friend, a man may not live in the same state.”

Li Mow Gee smoked for a moment in silence, then continued:

“Thus reads the Book of Rites, most venerable Chang. And yet our friend Huber Davis is our friend.”

“If the tiger and the ox are in company,” quoth Mr. Chang squeakily, “let the ox die with the tiger.”

“Not at all to the point,” said Li Mow Gee in irritated accents. “Do not be a venerable fool, my father! I desire that a messenger be sent to my bazaar.”

“Speak the message, beloved of heaven,” responded the elder.

“In our safe,” said Li Mow Gee slowly, “is a three-armed candlestick of white jade, bound in brass and having upon its three arms the characters signifying chalk, charcoal, and water. It is my wish that this precious object be taken to my bazaar and placed there near the door, with a sign upon it putting the price at nine florins; also, that our clerks be severely instructed to sell this object to no one except Mr. Carefrew.”

Mr. Chang wet his lips.

“But, dear brother,” he expostulated, “this is one of the precious objects of the Heaven-and-Earth Society.”

“That is why I desire your permission to make use of it,” said Li Mow Gee. “Am I to be trusted or not? Is my sacred honor of no worth in your eyes?”

“But, to be sold to a foreign devil!” the junior partner exclaimed.

“That is my wish.”

Mr. Chang threw up his hands, not without a smothered oath.

“Very well!” he squeaked angrily. “But when this swindler, this murderer of honest folk, sees it for sale in your bazaar at so ridiculous a price, he will buy it and take it away, and laugh at Li Mow Gee for a fool!”

“If he did not,” said Li Mow Gee, pouring himself another thimble-cup of wine, “I should be a most wretched and unhappy man!”

III

A Chinese candlestick is meant to hold, upon a long, upright prong, a candle painted with very soft red wax, so soft that the finger cannot touch the paint without blurring and marring it. Otherwise, it is like Occidental candlesticks in general respects.

Reginald Carefrew, who had plenty of money in his pocket, but who had left Singapore in something of a real hurry, walked into the Benevolent Brethren Bazaar in search of silks and pongees to take home to Europe. The bazaar, which bore no other name, confined itself almost exclusively to such goods. In the front of the shop, which was upon one of the half-Dutch streets overlooking the harbor, were strewn about a few objects of brass, bronze, and the cheap champlevé cloisonné which are made for tourists.

Almost as he entered the place, however, the vigilant eye of Carefrew discovered a very different object, placed in a niche which concealed it from view of the street. It was no less than a candlestick of three arms, a most unusual thing; also, it was made chiefly from jade, highly carven, while the upright prongs and the trimmings were of brass. Altogether, a most extraordinary and wonderful candlestick—priced at nine florins.

Carefrew, naturally, thought that his eyes lied to him about the price. With excitement twitching at his nerves, he walked back and bought several bolts of silk, ordering them sent to him at the residence of Huber Davis.

Then, casually, he inquired about the candlestick of the smiling clerk.

It was, he learned, a worthless object, left here for sale long years ago by some now forgotten Hindu native, or maybe Arab; one could not be certain where years had elapsed and the insignificance of the object was great, but of course the books would show, should it be desired that the affair be looked into.

Naturally, Carefrew did not desire the affair looked into, because some one was then sure to discover that the candlestick was real jade. There was no doubt about that fact, and he was too shrewd to be deceived. A passing wonder did enter his mind as to how yellow men, especially men of T’ang from the middle provinces, could have supposed the candlestick to be worthless; but, after all, mistakes happen to all men—and other men profit by them. The candlestick was not a wonder of the world, but was worth a few hundred dollars at least.

So Carefrew laid down his nine florins, and carried his purchase away with him, wrapped in paper.

Carefrew found the bungalow deserted except for the native boys; the siesta hour was over, and Huber Davis had departed to his office. After a critical inspection of his purchase, resulting in a complete vindication of his former judgment, Carefrew set the triple candlestick on the dining-table and swung off to Chinatown again.

It was the most natural desire in the world to want to complete that princely candlestick with appropriate candles; particularly as Carefrew was now on his way to Europe and would have little further chance to get hold of the real articles.

Being downtown, Carefrew dropped into the office of Huber Davis, and found a letter which had come in that morning by the coast steamer from Batavia. The letter was from Ruth, confirming her passage on the next fast Royal Mail boat. Upon the fourth day from this she would be at Sabang, having taken passage as far as Colombo for herself and Carefrew, whose loose business ends she was arranging.

“I suppose,” inquired Huber Davis in his cool, semi-interested fashion, “you did not take her into your confidence regarding your late financial ventures?”

“Why in hell would I want to bother her about finances?” retorted Carefrew, with his bold-eyed look. “She doesn’t understand such things.”

“Damned good thing she doesn’t, perhaps,” reflected the other. “Well, see you later! By the way, here’s the receipt for that thirty thousand you laid in my safe.”

“I don’t want receipts from you.” protested Carefrew virtuously.

“Maybe not, but I want to give ’em to you,” and Huber Davis smiled.

“Damned rotter!” reflected Carefrew as he passed on his way.

He was not acquainted in or with Sabang. It was not hard to see what he desired, however, and presently he succeeded beyond his expectations. A dirty window filled with dried oysters and strings of fish and other things, after the Chinese fashion, carried also a display of temple candles. They had only appeared in the window that morning, but Carefrew did not know it, and would not have cared had he known it.

Carefrew stopped and inspected the candles, which were exactly what he wanted. There was a half-inch wick of twisted cotton, around which was built the candle, two inches thick. The outside was gaudy red and blue with sticky greasepaint, and at the lower end was a protruding reed four inches long.

By this reed one might handle the affair without marring the paint, and into this reed fitted the upright prong of a candlestick. The whole candle was bound inside a big joint of bamboo, which held it without harm.

Noting that there was one candle on display, and that there seemed to be but two more with it, Carefrew entered the shop, found the proprietor, and priced the candles. The proprietor had brought them from Singapore ten years previously and did not want to sell them. However, Carefrew offered a ten-florin note, and carried them home.

He was, for the moment, a child with a new toy, completely absorbed in it, and utterly heedless of all the rest of the world. Another man might have had weights upon his conscience, but Reginald Carefrew was not bothered by any such.

He laid the three bamboo cylinders upon the dining-table, after it had been laid for dinner, and opened them, cutting the shrunken withes that held them securely. The glaring red candles lay before him, and for a moment he pulled at his cigarette and studied them. Knowing what sort of candles they were, he tentatively touched them with his forefinger. The touch left a red blotch at the end of his finger, so soft was the greasepaint.

One by one he set them carefully upon the three prongs of his jade candlestick. One could not blame his ardent admiration. Even to an eye which knew nothing of Chinese art, the picture was exquisite; to one who could appreciate fully, it was marvelous. Candles and candlestick blended into a perfect thing, a creation.

“And to think that it cost me,” said Carefrew to his brother-in-law, when Huber Davis appeared, “exactly nineteen florins—ten of which were for the candles!”

Huber Davis gazed at the outfit appraisingly, a slight frown creasing his brow.

“If I were you,” he said after a moment, “I’d get rid of it, Reggy. You certainly picked up something there—but it doesn’t look right to me. You don’t catch John Chinaman handing out stuff like that at a bargain price, not these days!”

“Bosh!” ejaculated Carefrew. “A pickup, that’s all—one of the things that comes the way of any man who keeps his eyes open.”

Huber Davis shrugged his shoulders.

“Got the red stuff on your hands, eh?”

Carefrew smiled vaguely—his smile was always vague and disagreeable—and glanced at his hands. He rubbed them, and the red spots became a fine pink rouge.

“I’ll light ’em up,” he said, “and then wash for dinner, eh?”

Huber Davis said nothing, but watched with cold-growing eyes as Carefrew lighted the three wicks. He was somewhat long in doing this, for they were slow to catch. When they did flare, it was with a yellow, smoky light that sent a black trail to the ceiling. Carefrew turned to leave the room, but the voice of his brother-in-law brought him about quickly.

“Wait! I had a letter today from my agent in Batavia, Reggy. He said that Ruth had been in the office—he was helping her straighten up some of your affairs.”

A subtle alarm crept into the narrow eyes of Carefrew as he met the cold, passionless gaze of Huber Davis.

“Well?” he demanded suddenly. “What is the idea?”

“You didn’t say anything was wrong with Ruth,” said Huber Davis calmly. “But my agent mentioned that her right arm looked badly bruised—her sleeve fell away, I imagine—and she said it had been a slight accident. What was it?”

Carefrew’s brows lifted. “Damned if I know! Must have hurt herself after I left, eh? Too bad, now—”

He turned and left the room, whistling. Huber Davis gazed after him; one would have said that the man’s cold eyes suddenly glowed and smoldered, as a shaft of sunlight suddenly strikes fire into cold amethyst.

“Ah!” he muttered. “You damned blackguard—it goes with the rest, it does! You’ve laid hands on her, and yet she sticks by you; some women are like that. You’ve laid hands on her, all right. If I could prove it, by the Lord I’d let out your rotten soul! But she’ll never tell.”

Presently Carefrew’s gay whistle sounded, and he sauntered back into the dining-room.

“That’s queer!” he observed lightly. “The red ink wouldn’t come off. I’ll get some of your cocoa butter after dinner and try it on. Hello! Real steamed rice, eh? Say, that’s a treat! I despise this Dutch stuff.”

IV

Huber Davis, who had an excellent general agency, always dealt with Li Mow Gee in silks and fabrics—that is, he dealt with Li Mow Gee direct, which meant that he was one of a circle of half a dozen men who did this. Not more than half a dozen knew that Li Mow Gee had any particular interest in the silk trade.

Two days after Carefrew had brought home the candlestick and appurtenances thereof, Huber Davis sought the Street of the Heavenly Elbow, and entered the dingy cubby-hole which opened upon the widening shop of Li Mow Gee. That morning Carefrew had carefully tied up his temple candles again and was preparing to pack his purchases of silk.

After a very short wait Huber Davis was ushered through the fan-shaped apartments to the hub and kernel of Li Mow Gee’s enterprises, where the owner sat before his charcoal brazier, heated his rice-wine, and gazed upon his nudes—to call them by a polite name—with never-flagging appreciation.

Li Mow Gee greeted him cordially and ordered tea brought in. Huber Davis said nothing of business until the tea had been poured, and then he did not make the usual foreigner’s mistake of drinking his tea. He knew better, for Li Mow Gee followed the tea ceremony implicitly.

When he had concluded his business in silk Huber Davis took from his pocket a sheet of note-paper upon which were inscribed three ideographs.

“I wish you would do me a favor, Mr. Li,” he said. “My brother-in-law is visiting me, and the other day he picked up a candlestick bearing these characters. For the sake of satisfying my own curiosity, I copied the characters and put ’em up to my clerk, but he said they were very old writing, and that only a university man like yourself could decipher them correctly. So, if you would oblige me—”

Li Mow Gee took the paper and glanced at the three ideographs. He wrinkled up his dissipated eyes and gazed at Huber Davis. Then he picked up his pipe and began to smoke.

“Your clerk was a wise man, Mr. Davis,” he said quietly. “You have heard of the Heaven-and-Earth Society, no doubt?”

Huber Davis started. “You mean—”

“Exactly, my friend. How your esteemed brother-in-law picked up this candlestick I cannot imagine; but it is marked with the emblems of that society, of which I am a member.”

Huber Davis whistled. He knew that not all the power of the Manchu emperors had availed to stifle that secret fraternity, and he knew that Reggy Carefrew was playing with hot coals. But he kept silence, and presently he had his reward.

“If we were not friends,” said Li Mow Gee reflectively, “and if the ties of friendship were not sacred and honorable things, I would say nothing to you. Even now it may be too late; as to that I cannot say, for others may know that your brother-in-law made this purchase. But, because we are friends, for your sake I shall try to help you.”

“I appreciate it,” said Huber Davis, not without anxiety. His anxiety was warranted. “If you will give me advice it shall be followed implicitly, I assure you.”

Li Mow Gee smoked until his long pipe sucked dry.

“Well, then, bring to me that candlestick and whatever else was with it—candles, perhaps. I will make good whatever sum your honorable relative expended, and I will see to it that the matter is adjusted in the right quarters in case trouble has arisen. But, remember, time is an element of importance.”

“In half an hour,” said Huber Davis earnestly, “I shall return with the things.”

Li Mow Gee picked up his cup of tea, signaling that the interview was ended.

Huber Davis dropped business and hurried home. If he could have reconciled it with his conscience, he would have let matters alone in the confidence that before a great while Reginald Carefrew would be removed from this mortal sphere; but Huber Davis had a stiff conscience. Besides, there was Ruth. If Ruth still loved this swindler, Huber Davis intended to protect and further him—for her sake. There was a good deal of the old conventional spirit in Huber Davis.

He expected trouble, and was prepared to handle it firmly; but he wanted to avoid a scene if possible. So, finding Carefrew engaged in packing, he lighted his pipe and watched for a few moments without broaching the subject on his mind.

“How much,” he said at last, “do you expect to get for that candlestick if you sell it?”

Carefrew looked at him in surprise.

“Eh? Think I have some judgment, after all, do you? Oh, I ought to get a hundred easily.”

“Well, see here,” proposed Huber Davis, “I do like the thing, Reggy. Tell you what: I’ll give a hundred and twenty-five, cash down, if you’ll turn it over. Eh?”

Carefrew grinned. “Hundred and fifty takes it,” he said.

“You nasty son of—” thought Huber Davis. With an effort he controlled himself and produced his check-book. By the time he had written the check Carefrew had unpacked the candlestick. Huber Davis remembered the negligible remark which Li Mow Gee had made about the candles.

“Throw in the candles,” he said, waving the check to dry it. “I want ’em.”

Carefrew assented with a laugh. “You are welcome, old boy! I’ve never yet got that damned red stuff off my hands; nothing touches it. It’ll have to wear off. And it itches!”

Huber Davis paid little attention to him, but picked up the wrapped candlestick, took the two-foot bamboo sections, and started off down the hill.

“Now, you dirty whelp,” he mentally apostrophized his relative, “I’ve got you out of a cursed bad situation, only you don’t know it and would never believe it!”

Upon reaching the funny-bone in the Street of the Heavenly Elbow, he sent in his name and was ushered quickly to the presence of Li Mow Gee.

“There’s the stuff,” he said, with a deep breath of relief. “And I’m in your debt, Li. I’ll remember it.”

Li Mow Gee smiled slightly, ironically, as though Huber Davis might stand more in his debt than was known or dreamed of.

“Don’t forget the price,” he said quietly. “Accounts must be kept straight, my friend. What was the cost of this thing?”

“Nineteen florins, but don’t bother about that,” returned the other, saying nothing of his payment to Carefrew.

“Pardon me, but it must be made all straight.” Li Mow Gee counted out nineteen florins from his pocketbook, which Huber Davis accepted. “Now a little wine to our friendship, eh?”

Huber Davis drank a thimble-cup of hot wine and took his departure, feeling that his hundred and fifty dollars had been well spent, having pulled Carefrew out of a bad situation, and thereby benefited Ruth.

Li Mow Gee, alone with his charcoal brazier and his pictures and his pipe, left the wrapped candlestick as it was, but took the three candles in their bamboo wrappings and opened a door in the wall where no door appeared to sight. He entered a long, narrow room which contained a great many queer little bottles, many of them old Chinese flasks carved from agate or amethyst, and a long table; the room did not appear in the least like a laboratory.

When he had laid the candles upon the table Li Mow Gee carefully cut the wrappings, but left each candle lying in its cradle of bamboo. Then he took a large glass bottle from the corner, and poured oil over each candle until the bamboo cradles were filled. When he lighted a match and ignited the oil one realized that the table was of ironwood.

Li Mow Gee stood placidly watching while the three candles became reduced to scorched and smoking masses of black grease, then blew out the lingering flames, cleaned the débris from the table into a brass jar, and returned to his own apartment.

When he had emptied six cups of wine he clapped his hands four times, and promptly the venerable Mr. Chang appeared, removing his spectacles and blinking.

“I return to your keeping the honorable candlestick of our lodge,” said Li Mow Gee, “and I thank you for the loan, venerable master.”

“Are the spirits of the dead satisfied?” queried Mr. Chang.

Li Mow Gee poured himself another cup of wine and positively grinned.

“If they are not,” he said, this time in English, “they are damned hard to please!”

It will be observed that Li Mow Gee was out nothing whatever—except certain obscure labors—for while he had paid Huber Davis nineteen florins, Carefrew had paid nineteen florins to agents of Li Mow Gee. And this, according to Oriental notions, was the acme of honor and propriety.

V

The Royal Mail boat, the “through packet” on which Ruth Carefrew was coming, held due for Sabang late in the afternoon. Upon the morning of that day Huber Davis went to the wireless station and sent a message to Ruth, aboard the steamer, to prepare to leave ship at Saban and cancel passage.

Then Huber Davis returned to his own bungalow, and met Dr. Brossot as the latter was leaving.

“Well,” inquired Huber Davis quickly, “what’s the trouble?”

The physician shrugged his shoulders.

“It has come, that’s all. Java has been swept, the west coast of Sumatra has seen them die by thousands, and now—it is here.”

“The influenza?” said Huber Davis.

“It can be nothing else. High temperature, and you say he had chills yesterday; much pain, everything according to the ritual. I am sorry, Mynheer Davis; his room had better be quarantined, of course.”

“You think it is dangerous?”

“No. The danger, of course, lies in the pneumonia afterward. We must wait and see?”

After this, events moved fast. At noon the doctor arrived again, in response to a hurried message from Huber Davis. An hour later the two men sat in the study of Davis.

“But, Brossot,” said the latter, staring at the doctor, “what the devil was it, then? You say there was no pneumenia—”

The honest Dutchman shook his head. “Mynheer, upon my word of honor, I don’t know! I shall call it heart-failure; that’s what we all say, you know, to conceal our ignorance. The Chinese would say that he had swallowed gold, another polite way of saying the same thing. If you want an autopsy—”

Huber Davis rose, paced up and down the room, his brow furrowed.

“That’s not half bad, that Chinese saying,” he muttered. “No, Brossot, no autopsy. His wife arrives this afternoon, you know; my sister Ruth. Swallowed gold, did he? I believe it’s the truth, at that!”

But he never thought again about the red grease-paint on those candles, and he did not know anything about Li Mow Gee having a little laboratory—in the Chinese style—opening off his apartments. Nobody knew about that laboratory, except Li Mow Gee; and Mr. Li never boasted of his methods.

PLANE JANEby Frederick C. Davis

Originally published in Adventure, August 1928.

Don’t go wonderin’ if I’m a expert on the subject, but ain’t there a kind of girl that looks her prettiest when she’s wearin’ a kitchen dress and rollin’ out biscuits? And ain’t there another sort of girl who transforms herself into the most beautiful when she appears in a filmy evenin’ gown and waits for you to waft her out into the moonlight? Then there’s another that becomes the one and only when she is wool from head to toe and cuddlin’ beside you on a toboggan. And there’s one who is a shade above Venus when she comes slashin’ out of the surf glistenin’ and lithe and fresh.

Jane Alton wasn’t any of these kinds, but, oh, what a dream she was in a flyin’ suit! Jane was born to ornament the air. With a stick in her hand and flyin’ joy in her eyes, she was an angel—and, of course, bein’ an angel, she belonged in the sky. She put herself there every chance she got!

It was a mornin’ full of smooth air and high visibility when Jane came rompin’ around the hangars, shinin’ leather all over and, seein’ us, smiled brighter ’n the sun and ran straight for our plane.

Ned Knight was in the fore cubby, jazzin’ the motor, ready for a take-off. He grinned and remarked over his shoulder:

“Benny, ol’ nut-twister, here’s where you lose your seat, back there. Jane’s all set to take another trip to her home port, Heaven, and there’s no use tryin’ to stop her. Better start gettin’ out.”

I’d already begun startin’, and I was all the way out when Jane came up laughin’.

“Thank you, you ol’ darlin’,” she said to me, and I ain’t so old, either. “I can’t wait another minute to get up into all that glorious sky. Ned, would you mind changin’ back to Benny’s seat?”

“What!” barked Ned. “Listen, Jane. I’m takin’ this little Alton up for a check-ride. Your Dad is waitin’ for the data on it. Just this time won’t you ride in back, just this once, and lemme—”

“Ned Knight,” came back Jane, “am I not the holder of a pilot’s license?”

“Yes, but—”

“Haven’t you, my only instructor, pronounced me to be a flyer equal to any other you know?”

“You sure are, Jane, but—”

“Can’t I handle that stick and do a good job of gatherin’ data myself?”

“I’m not sayin’ you can’t, but—”

“Do you want me to go up in another plane, without you, Ned Knight?”

“No!” said Ned, and so he began gettin’ out!

Me, I couldn’t ’ve held out half that long against Jane Alton. I was plenty crazy about that girl, but bein’ only a grease-monkey, and havin’ a map resemblin’ a mauled-up bulldog’s, I confined myself to bein’ just her slave. Ned Knight, however, being the best flyer in the state, and the handsomest in six, got a lot of time from her. I suspected maybe that there was some kind of romance goin’ on there, between the flyer and the daughter of the plant owner, ’cause they flew a lot together, those two.

So, with Ned back in the rear pit, Jane climbed into the front one, settled to the controls, jazzed the motor, and waved one tiny gloved hand to me. I socked the blocks; she stepped on the gas; and the Alton was off. It trundled to the other edge of the sand, and Jane pulled it up neatly; she circled twice, got herself a nice lot of altitude, rode a few air waves in sheer joy, and then deadheaded across the blue.

Now and then she cut the motor. Say, there wasn’t any tellin’ what went on between them two, all alone up there, so close to Heaven! I know they didn’t exactly dislike the open solitude of that sky! I remember once, when Jane hopped out of the Alton, after a spell of hootin’ with Ned, she said to him: “I love to be all alone with you up there!” And Ned was never quite the same when he came down from a flit with Jane, anyhow!

Well, while the Alton was banking and skimming at about a thousand, Robert Bennett Alton himself came out onto the field. He was owner of the field, and of the factory where the Altons were made. He was manufacturing a sturdy, speedy, almost foolproof plane that was just about the ultimate in aviation on a small scale. A man dissatisfied with anything short of perfection—that was Alton. And a fine man, in and out from the heart. He stood beside me, watching his little moth weave across the sky.

“What a ship!” I said. “What a joy of a ship!”

“It seems to handle well, Benny,” was all Alton said. “What—what’s that?”

Starin’, I went cold. From the front of the plane some black smoke spouted out; and then came the flashin’ of fire. Fire it was! The nose of that plane was bein’ licked by the flames leapin’ back from the engine. One second it had been all o. k., and the next it was pushin’ a bonfire through the sky! If the fire reached the gasoline lines and the tank—if it kindled the linen—it meant disaster! And I, myself, I had inspected that ship to make sure it was o. k. All but passin’ out, I continued to stare, and Mr. Alton got as white as the clouds.

“Benny, who’s pilotin’ that ship?”

“Jane!”

“What!”

Now the plane was sideslippin’ away from the flames; it tore off them, and they disappeared.

“And Jane knows her stuff!” I shouted.

Once havin’ snapped away from the danger, Jane dove at full throttle, but the fire flashed out again, worse than before. As soon as it did, Jane sideslipped again, and the wind put the fire out. This time when she recovered she banked steep, gradually losin’ altitude and made for the T. Mushin’ out, she cut the gun, and the Alton glided for the sand. The fire popped out again, not so bad this time, but bad enough!

The burnin’ ship trundled in, and before it stopped Ned Knight was out of it. Jane jumped right behind him. Ned scooped up sand and threw it on the fire, and Jane worked just as fast. Mr. Alton and me and some of the other boys ran for the ship, but by the time we got there, the fire was all out.

Ned Knight, plenty mad, stepped up to me chin first. “Benny, your job is to keep these ships in trim, ain’t it—’specially this one, that’s goin’ to fly the race—or was! Then how come the timin’ is off, and fire got sucked back into the carburetor? I’ll bet my hat that the screen and drain is in bad shape, too, you—. Good gosh!”

“Well, I got it out all right, didn’t I?” inquired Jane, who seemed to think that any scrape wasn’t very bad if she got out of it alive.

“You sure did! You got us out like a veteran. Jane, you’re all right. Benny, dang you—”

I wasn’t wastin’ time standin’ there and bein’ bawled out. I put my head into that motor, and it took only a minute for me to find out that some monkey business had been goin on—grease-monkey business! The engine had been tampered with. Our pet Alton! The ship we were dressin’ for the race! And with Jane in it! Lord!

I whirled around and barked out my troubles. And then there was plenty of quiet for a minute.

* * * *

Ned Knight moved first. Some other members of the hangar crew had come out to share the excitement. He singled out a pilot named Stud Walker, and stepped right up to him. Ugly eyes that man had, and an ugly face, and an ugly heart—Walker. His eyes sort of flashed with fear, and he tried to back away, but Ned had him nailed.

“Walker, lemme ask you some questions! Last night, while I was fussin’ around the field, I heard somebody inside this Alton’s hangar. That was strange. By the time I got it unlocked, and went inside, the noises stopped, and the hangar was empty. But I found a hole in the sand, under the tin wall, that was fresh dug, and that hole was hid by two empty oil barrels. You know anything about that? I’ll answer for you. You know all about it. You’re the man that tampered with the plane!”

“You can’t prove—” Walker gulped.

“Your guilty face proves it for me! I’m goin’ to smash—”

Ned began to sail in with both hands and feet, but I grabbed him. While he was talkin’, two other greaseballs had got behind Walker, and blocked his retreat. Also, they kept Ned from killin’ him. And right then Mr. Robert Bennett Alton himself stepped up and spoke.

“Ned, if you’re accusin’ this man of tamperin’ with that plane, I hope you can prove what you say.”

“Mr. Alton,” Ned came back, “some time ago I caught Walker tappin’ a gin bottle on the field, and ever since then I’ve been watchin’ him. A few days ago he acted funny. I watched closer. After dark a sedan drew up, and Walker got in. The car stayed, and I watched it. Inside it was Gifford, at the wheel—Gifford, of the Stormbird people. He and Walker were talkin’ low. Then I saw Gifford pass money to Walker. That is proof enough for me that he’s in Gifford’s pay, working against us. He was clever enough to jim the plane so I couldn’t find the trouble last night, but he’s got now!”

Walker looked plenty sick. Alton looked at him, and he couldn’t look back. He might ’ve killed Ned Knight and Jane—Jane!—with his trick, done for pay. He couldn’t face the man that had hired him out of good faith.

“Walker, you look guilty!” Alton spoke up. “You’ve tried to cripple us in favor of the Stormbird people—so they can win over us, of course, in the air derby tomorrow. Thank the Lord you won’t have a chance to get in any more of your dirty work! The Stormbirds are so afraid that we’ll outfly them that they have to hire crooks to beat us, eh? Do you know, Walker, that you could be jailed for what you’ve done?”

Walker was white around the gills.

“Walker, I don’t want to bother with you. I think too little of you and what you’ve done to prefer charges against you. Now, Walker, get off this field. Get off! If you show your face on it again, man, I’ll break you with my bare hands!”

Alton didn’t usually say much, but this was plenty for the occasion, and he meant every word. Alton’s contempt was worse than a lickin’ for Walker to take. Let loose, he shambled away, looks of disgust and hate followin’ him. When he disappeared around the hangars, the field seemed like a better place to stay.

Mr. Alton spoke quietly now to the boys, askin’ ’em to look over the planes careful, suggestin’ that a guard be put around the hangars tonight so that nothin’ could happen to the planes before the start of the air race the next day; and they’d better keep a gun handy; and—

“Ned!” Jane called out, not bein’ able to hold herself in any longer. “Please, let’s get another plane out and go right back up!”

* * * *

“Jane,” Mr. Alton said, “I want to talk with Ned a little, so you’d better let the flyin’ go a while. Benny, is that ship damaged much?”

“No, sir,” I answered. “By adjusting the timer and putting in a screen, and some new ignition wires—they’re burned off—she’ll be shipshape again.”

“Start on it right away,” Mr. Alton told me. “Ned, how did the ship feel today?”

“Better than ever before,” Knight answered. “Jane was at the stick, but I could feel the pull of the new prop. We get the proper revs now when we’re climbing.”

“The stabilizer?”

“Works like a dream. The ship’s as steady as a Rolls Royce on Fifth Avenue and she stays that way. Also, it’s easier to hold her head up. And the ailerons can be used when she’s throttled way down—that’s somethin’ that’s improved with the new prop and stabilizer. She’s ready for any race now, Mr. Alton.”

“Good!” said the Boss.

The boys’d been helpin’ me to roll the plane tail-to into the hangar, and then, leavin’ Mr. Alton, Jane, Ned and me in there alone, they went back to work. I tore off the old ignition wires while Mr. Alton talked.

“Ned, are you ready to fly your best tomorrow? Goin’ to reach Curtiss ahead of all the other entries, are you?”

“Sure he is!” spoke up Jane. “I’m his mascot!”

“I think your plane is a better flyer than any other in the line-up, Mr. Alton,” Ned answered. “The Stormbird will tail us, but we’ll win.”

“I hope so!” Mr. Alton came back, sighin’. “Ned, I’m goin’ to take you into my confidence. You’re goin’ to pilot that ship tomorrow, and Benny will be along with you, and you both ought to know that I’m bankin’ on you boys heavily. Aside from the purse—which, of course, the pilot is goin’ to keep, for he’s the man that is goin’ to earn it—the reputation of the Alton is at stake. The number of accidents that have happened recently in Altons has given us a black-eye, Ned—you know that.”

“People’ll forget that when we zip across the finish field first,” Ned answered.

“They will—if we win,” Mr. Alton answered. “That will help. But that’s not all. That ill will has hurt our business. We have been runnin’ on a shoestring—and we’ve just about reached the end of it. We need the winnin’ place in this race because of the good it will do our business. If we don’t come in number one, Ned, I’m afraid that we’ll have to be closing up the plant soon.”

Ned got pale, and I forgot work, and Jane listened plumb excited. Mr. Alton was talkin’ in a low, serious tone. Since the Alton plant was all any of us had in life right then, it was serious. We knew business had been bad, but we never suspected it was that bad—never suspected that this air derby was becomin’ a life and death matter for Alton planes.

“I’ll explain a little more,” Mr. Alton went on, solemn and quiet. “You know that the United Airways is holding up a large order of planes—enough to keep us busy for the better part of a year—and will place its order dependin’ on the outcome of the race tomorrow. They’re lookin’ for speed and stamina, and they think they’ll find it in the winnin’ ship. I had a talk with Finley, the manager, last night. ‘Win the race, and I’ll place my order with you,’ he said. That’s how the matter stands. And that United order, if we get it, will save our lives.”

Lord!

“There are other orders in the balance, too,” Mr. Alton went on. “The government is going to give the winner some places in the air mail and border patrol fleets, to replace the antiquated DeHavilands. There’s a passenger airport in Texas that I’ve been tryin’ to land, that’s waitin’ for the winner to take the order away from it. I could name half a dozen more such examples; but it isn’t necessary.

“You understand, Ned, that when you fly tomorrow, you’ll be flyin’ to win—win not only the purse for yourself, but a new life for us. And if you lose—but we won’t think about that now. You’re goin’ to win.”

“Yes, sir,” said Ned. “We’re goin’ to win!” He gave a look at Jane, and Jane’s eyes sparkled. “There’s still another reason why I’m goin’ to win, Mr. Alton!”

“There is?”

“A pilot that ain’t married usually hasn’t got a habit of savin’ his money—and I’ve spent all mine, till lately. But if I had to buy a house and a lot of furniture, right now, I couldn’t do it. But with that purse in my pocket—five thousand dollars—it wouldn’t be so hard! I want to do that, Mr. Alton. I want to win that race, and then step up to you, and say, ‘Sir, I want to marry your daughter!’”

Mr. Alton smiled. “From Jane’s conversation at home, which has just two subjects—flyin’ and Ned—I’d suspected the situation.” He chuckled. “I’d rather have a pilot for a son-in-law than anybody else, and of all the pilots I know, you rate highest with me, Ned. Well, after you win that race, and step up to me, and say your say, I’ll talk with you about it!”

“Thanks!”

Mr. Alton walked out of the hangar, havin’ said his say to us—which was plenty. For a few minutes I was stunned. Things was comin’ too fast for me. That whole big plant, out there, was in danger of vanishin’. Those peppy little Altons were in danger of eventually droppin’ out of the air. Altons had been the subject of our talk and dreams for years, and if they went—it would be worse than a death in the family. And yet, there the whole matter was, flat up and lookin’ us in the face—and all of us swore, right then, that this Alton had to win that race!

I turned and got to work on it—and how I began to work!

Somethin’ that happened behind me sounded a whole lot like a kiss.

“So!” said Jane Alton. “You think, do you, Ned Knight, that you’re goin’ to win me in a race as though I was a kewpie doll on a rack?”

“Why—”

“And if you don’t win the race, you won’t ask me to marry you at all?”

“Well, gosh!”