22,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

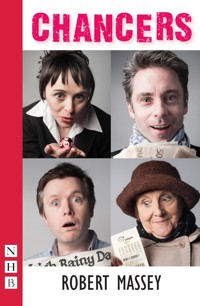

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

In From Able to Remarkable: Help your students become expert learners, Robert Massey provides a pathway to help teachers guide their students through the gauntlets of the gifted, the underpasses of underachievement and the roadblocks to remarkable on their learning journeys. What makes remarkable students remarkable? Attributes such as resilience, curiosity and intelligence may come to mind and we might also add others, such as intuition and tenacity. But what has helped make them what they are? Were they born this way, or did their 'remarkabilities' emerge during their schooling? Such questions may make teachers feel uneasy, prompting them to reflect on the sometimes limiting scope of what is often labelled as 'gifted and talented provision' in their school. Robert Massey argues, however, that these remarkabilities are there, latent and dormant, in many more students than we might at first acknowledge. In From Able to Remarkable Robert shares a rich variety of practical, cross-curricular strategies designed to help teachers unearth and nurture these capabilities and signpost a route to the top for every learner. Informed by educational research and evidence from the field of cognitive science, the book talks teachers through a wide range of effective teaching and learning techniques all of which are appropriate for use with all pupils and not only with top sets or high attainers. Robert also shares ideas on how teachers can improve their students' abilities to receive, respond to and then deliver feedback on both their own work and that of others. To complement the feedback process, he presents practical methods to help teachers make questioning, self-review and greater student ownership of their questioning within lessons a staple of day-to-day classroom interaction. Venturing beyond the classroom, the book also explores approaches to whole-school provision for high-attaining students and offers some robust stretch and challenge to educational leaders in considering what widespread excellence in education might look like. Suitable for teachers and gifted and talented coordinators in both primary and secondary schools.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Foreword by David Didau

At the start of my career as a teacher I worked for some years as a gifted and talented coordinator. Back in the early 2000s, the government of the day decided that more ought to be done to challenge the intellectual development of more able children, and, in turn, schools were tasked with the identification and monitoring of the small percentage of students at the top of the ability curve. As this was my first promotion, I threw myself into this task with a will. I combed through the results of cognitive ability tests, cross-referenced with attainment data and teachers’ reports from the pupils’ primary schools and drew up a list of anointed individuals who were to receive a bespoke package of educational excellence. I organised visiting speakers on a range of mind-broadening topics, funnelled students into improving extracurricular activities and generally made sure that they, their parents and the other teachers in the school knew just how special they were.

It was years later that I began to suspect that these endeavours were, although well-intentioned, entirely wrong-headed. It’s become clear to me now that educational attainment is based, in large part, on how knowledgeable you are; the more you know, the better it’s possible to think. No one, no matter how clever they believe themselves to be, can think about something they know nothing about. And the more you know, the easier it is to learn even more about the world. Academic success is founded on a triumvirate of background knowledge, the good fortune of having been born with an above average working memory capacity, and the determination to work hard and practise, practise, practise.

School is a sorting machine designed to separate the academic wheat from the chaff. Children who are identified as able are treated as able. They’re put into ‘top sets’ or academic streams and fed more challenging content at a rapid pace. Children who present as being less able are put into more ‘nurturing’ environments where they’re given less challenging material at a much slower pace. All this ensures a self-fulfilling prophecy; if children were not more or less able at the start of the process, they most certainly are by the end. So why would anyone concerned with the attainment of the most able focus on those who have already got themselves noticed?

While we may not remember how or why we found ourselves on a particular academic path, our route through education was almost certainly the result of some sort of feedback. Most human beings enjoy doing what they’re good at and avoid what they’re bad at wherever possible. If we’re fortunate enough to find it easy to turn letter combinations into sounds, we’re also likely to enjoy doing so. The more you do anything the better you get at it. A small early difference in the ease with which we accomplish a task is very likely to turn into a large difference over time. The result is, some children become fluent decoders and quickly move from learning to read to reading to learn. Because they read, they fill their minds with information they find much harder to acquire independently and their minds take on the qualities of intellectual Velcro: school stuff sticks.

But those who struggle soon perceive the difference between themselves and those fortunate peers they perceive as being ‘more able’. Somewhere along the line, many children seem to acquire the belief that hard work and effort are a sign of being thick. Children who feel themselves to be ‘rubbish at school’ are likely to search for any other area at which they can excel – and, for many, this leads them to practising less at those things rewarded by the education system and, in far too many cases, more at those things teachers consider undesirable or anti-social. Maybe they become brilliant skateboarders, maybe they’re fantastic at playing computer games, possibly they’re amazing at applying make-up, but the belief that they’re not cut out for school will probably be proved correct day in, day out. Correspondingly these children can sometimes seem to have minds composed of intellectual Teflon.

This no doubt sounds unnecessarily brutal, and maybe it is, but it certainly isn’t fate. There is another way. The trick – if we can call it that – is to assume that all children are capable of remarkable things and, crucially, to treat them as if this is true even – and especially – when they don’t believe it themselves. Robert Massey’s book is written with this very much in mind. From Able to Remarkable is a guide for those who want desperately to believe that school can make a difference, that the way teachers act and interact with young people matters, and that every child is (or can be) remarkable. Robert’s conceptualisation of the ‘expert learner’ should be seen as a message of hope and optimism. Being remarkable doesn’t have to be the preserve of the few and the fortunate. With careful guidance and support, every child can become more expert at learning – and this, in turn, is likely to lead to a more positive and successful experience of academic education. Of course, not every child can or will become the next Einstein or Mozart, but that hardly matters. The real message is this: we are all capable of so much more than we believe.

David Didau, Algajola

Acknowledgements

Family first. Tom, Anton, Molly, Beth and Felix: this book is about you and for you. You have all been on your own remarkable learning journeys, and one of the joys of parenthood is in observing and sharing what each stage involves, and will continue to involve, for each of you. Paul and Maggie Greensmith have offered me wisdom and practical support as retired former teachers of distinction, as well as lending truth to the maxim that teaching runs in families. This book is dedicated with love to my wife, Annie, herself an outstanding teacher, coach and role model.

My own learning journey started in Luton thanks to two men who lived in entirely separate compartments of my young mind. Roy Meek, choirmaster and church organist extraordinaire, led by patient and kind example. Michael Miller at Challney Boys’ High School was that teacher for me – the one who opened every door and made learning an essential requirement of life. I’ve written a little about him in this book but nothing like enough. A mutual love of music meant that these two polymaths knew each other in real life, of course. I hope they know the impact they have had on so many young people.

As the first person in my family to go to university, the conventional choice of a history degree took a twist as I was introduced to medieval attitudes, beliefs and events under the inspirational Christopher Allmand. Christopher’s integrity, kindness and generosity as a teacher and thesis supervisor have been lifelong legacies of my years in Liverpool, not to mention a model of good practice in their own right. At Bancroft’s, another fine teacher, Chris Taylor, took a rookie under his wing and showed me on a daily basis how much was to be gained from a hugely committed and dedicated classroom life: the same investment returned but with added interest. At Bristol Grammar School, I have been allowed the freedom to practise a lot of what I preach in this book, and I am grateful to every colleague, past and present, who has been part of this. If I name and thank Niki Gibbs, Paula Lobo, Andy Nalty, Mike Ransome, Richard Smith, Dan Stone and Colin Wadey, that is not to say that others have not contributed too.

Bristol schools have allowed me access to some of their great ideas and practices. This has included building meaningful networks and working partnerships, which are set to continue in exciting ways in the coming years. Two utterly inspirational primary heads, Inger O’Callaghan at Glenfrome School and Adam Barber at Henleaze Junior School, generously shared their time and expertise with me. Further afield, I have benefited from conversations with Mark Anderson, Alex Quigley and Nick Dennis. Watching Nick conduct the first TeachMeet I ever attended at the wonderful Schools’ History Project annual conference in Leeds some years ago was a turning point.

Without teachers sharing ideas, resources and opinions via blogs, tweets and teaching and learning conferences, books such as this would never be possible. I have profited over the years from hearing speakers as diverse as Daisy Christodoulou, Christine Counsell, David Didau, Tom Sherrington and John Tomsett: their knowledge and insight has been entirely my gain.

At Crown House Publishing, Caroline Lenton had the initial faith, which David Bowman and his team have exemplified since; my thanks to them all. My copy-editor, Emma Tuck, has brought clarity to confusion. Thank you to Russell Earnshaw for inimitable inspiration. Lastly, very special thanks to Nazuna Aida, once a high-attaining pupil at my school and now a remarkable illustrator of ideas. Naz, you have brought the text to life.

Contents

He paid the greatest attention to the liberal arts; and he had great respect for men who taught them, bestowing high honours upon them. When he was learning the rules of grammar he received tuition from Peter the Deacon of Pisa, who by then was an old man, but for all other subjects he was taught by Alcuin, surnamed Albinus, another Deacon, a man of the Saxon race who came from Britain and was the most learned man anywhere to be found. Under him the Emperor spent much time and effort in studying rhetoric, dialectic and especially astrology. He applied himself to mathematics and traced the course of the stars with great attention and care. He also tried to learn to write. With this object in view he used to keep writing-tablets and notebooks under the pillows on his bed, so that he could try his hand at forming letters during his leisure moments; but although he tried very hard, he had begun too late in life and he made little progress.

Einhard and Notker, Two Lives of Charlemagne (1969)

Introduction

Starting Our Learning Journey

When teachers say to me, ‘My job is to help kids reach their potential,’ … I say, ‘No, it’s not. Your job is to help them exceed their potential.’

John Hattie, ‘Visible Learning, Part 2: Effective Methods’ (2011)

What do your remarkable students look like? You may be thinking of adjectives such as resilient, creative, intelligent, interesting, interested, compassionate and more. We might add to the mix terms such as adventurous and intuitive – perhaps the very qualities enshrined on your school or college’s website as characterising your student body.

High attaining academically, these model students may also be excellent at drama, hit the high notes musically or play sport to a very good level, as individual players or as part of a school team. They will certainly be admirably adept time managers, able to juggle a raft of commitments and extra responsibilities, maybe on a school council or as prefects, all without seemingly missing a beat.

What has made them what they are? Were they born this way, or did their abundant capabilities emerge at primary school before they came to you? What has your school or college really done to help generate excellence in learning among these students? Such questions may make you feel uneasy, as they do me, prompting you to reflect on what is often labelled as ‘gifted and talented provision’ in your school. Perhaps, like me, you have been on external continuing professional development (CPD) courses or had some in-house training on this aspect of educational policy. And yet … shouldn’t we be producing more students like Emma, who went off to medical school, or Majid, who is now reading English at Oxford? We might think, ‘Those two were great when I taught them lower down the school, and they seemed to have it even then – that desire to do well and a bit of confidence. Yes, they were a pleasure to teach, but when I come to think about it, they weren’t the only ones in that year …’

This book is designed to help. We need to change the way we think about producing remarkable students in our schools. When we do, the outcomes will be impressive in their own right and we will have irresistible impacts on every child, and not just the high-attaining ones. By making room at the top available to everyone, we make access to the top possible for all. This is not a book about the education of an elite; rather, it signposts a route to the top for every learner on their individual learning journey. By getting this approach right much else will fall into place. Wholesale changes to what you already do are not needed, spending on expensive new software ‘solutions’ is certainly not needed and the search for the legendary philosophers’ stone, in the form of a particular magic teaching or learning technique, can be abandoned before it wastes your or anyone else’s time.

This book offers five big ideas regarding provision for high-attaining pupils:

All students can and should become expert learners. There is no separate category labelled ‘gifted and talented provision’.Teachers make a difference to the learning of high-attaining pupils: adults teach, students learn, students lead.Teaching to the top (and learning to the top) will make a difference because it will help to unlock the latent potential of every child in our classrooms.The learning journey for all our students is lifelong and is undertaken for its own sake – for the love of learning, not the passing of exams.Our expert learners will become remarkable students.1. Expert learners

Here is an extract from my own school’s (Bristol Grammar School) current mission statement:

We aim high … and are proud to do so, inspiring a love of learning, fostering intellectual independence, and promoting self-confidence and a sense of adventure amongst our young. We set our sights on excellence in everything we do.

If you look at your school website, curriculum documentation or school enhancement framework you will probably find similar statements championing high aspirations and achievements, outstanding results and everybody’s favourite, the growth mindset. There is nothing wrong with this. Indeed, it would be surprising and worrying were this not the case:

Pupils at Acacia Avenue Academy do OK. The ones with high IQs we leave pretty much to themselves and they get the great results we all need. Phew! Middling ones who are polite and well behaved make reasonably good progress and some of them even get to university. Weaker students we support well and get nearly all of them their core grade 4 passes so they can scramble their way into college and we don’t get hammered by Ofsted. Standards are high at Acacia!

I doubt that many of us would send our child to a school like this in Year 7. If there is even a grain of truth in the caricature it is worrying. And Ofsted thinks there is (as we will discuss in Chapter 1): schools are failing on a large scale to stretch and challenge our high-attaining (or potentially high-attaining) students. It’s not that as educational professionals we don’t know what we need to do in order to improve student achievement. To a large degree we do. It’s just that we don’t seem to be doing it, or not sufficiently well or often enough to make a difference. It’s what Dylan Wiliam (2018: 118), citing Stanford management professor Jeffrey Pfeffer, refers to as the ‘knowing–doing gap’. This book aims to help fill that gap.

The book will reiterate some of what we know – in fact, quite a lot of what we already know and do as part of good practice – and aims to help teachers and schools kick on from there to start doing what works more consistently. A key premise is that we may be looking at our current Year 9s and missing their latent potential to be everything we see in that mission statement ideal student checklist. Likewise, there may be bright and eager Year 7s in our daily gaze whose dormant qualities as expert learners we are overlooking.

Forget easy labelling such as gifted and talented. Every pupil that you and I work with is potentially a teacher and a learner capable of excellence. If this journey is not worth taking, or at least attempting, then I don’t know what education is for. Surely, it is worth doing for its own sake and for the greater good that will result. If we need more prosaic reasons, then Ofsted’s School Inspection Handbook (2018: 60) states unequivocally: ‘Inspectors will pay particular attention to whether the most able pupils are making progress towards attaining the highest standards and achieving as well as they should across the curriculum’. Quite rightly in my view, there is now an explicit reporting requirement concerning more able provision. The sense is that if provision for what Ofsted labels ‘more able’ pupils is satisfactory, then there is a good chance that other learning and teaching is likely to be achieving its aims. If not, then this is very much less likely.

2. Teachers make a difference

The second and most obvious proposition of this book is that we, as educators, have a large bearing and influence on the quality and quantity of the high-attaining students in our schools. It may be an alchemical process we don’t fully understand, and it may well be that we disagree as individuals and institutions about precisely what proportion of influence and effect that we, as teachers, have on our charges and what may come from hereditary, family and other outside sources. Nevertheless, there is a correlation – if not a measurable, causal effect – between what we do (or don’t do) and significant, lasting consequences for our students.

Despite the fact that we don’t fully understand how we shape and influence young people towards successful outcomes, this is not to suggest that we should be leaving learning to chance. This would be like saying that med school high-attainer Emma just emerged because a ‘bright student’ always comes along eventually. Instead, this book puts teachers at the heart of a modelling process which is more akin to coaching than traditional pedagogy. Techniques for questioning, for feedback and for team activities model excellent processes and outcomes, which are then taken on by students, modified and improved according to context and then applied. Teachers lead, students learn, students lead. This simple mantra empowers students to become their own agents of change. They become responsible for their own learning journeys. They may even meet the accolade to be found on posters and websites in just about any school or college in the country: independent learner.

Our attitudes and actions as teacher-counsellors, teacher-supporters, teacher-motivators and teacher-role models help these journeys to happen and to continue towards successful outcomes. They are not the preserve of first-class ticket holders only. This is coach-class travel at an affordable price for everyone.

3. Teaching to the top

Every teacher has a desk full of anecdotes about that dreadful Year 8 boy who later became a prefect and went on to read engineering at Cambridge, for example. Stories don’t make evidence but experience still counts for something. How dare we limit anyone’s potential? All our students have abilities and remarkabilities. Perhaps we just haven’t found them yet or they haven’t shown them yet. If our lessons, games practice, chess clubs and school musicals are replete, and I mean absolutely replete, with opportunities for these abilities to emerge, then that is a fully fledged, live action high-attainer programme in action. If every sequence of maths lessons contains some spark and ‘I never thought of that’ moments, if year group assemblies leave staff and students feeling positive about the day ahead, if the geography department really sit down and plan how to turn ‘routine’ GCSE fieldwork into something memorable because of the learning and engagement it brings, then remarkable things will happen. As Andy Tharby (2017b) tellingly puts it: ‘if we are to encourage more and more students to aim for the very top, then we must all play our part in the wider school culture – however immeasurable these actions may be’.

An academic culture needs to seep into every crack of conversation, meet-and-greet, lesson and assembly. Andy Tharby’s school, in a coastal town taking in pupils from a wide range of backgrounds, is not afraid to tap into and shape peer and whole-school culture. I believe that modelling teaching to the top leads, via encouragement and repetition, to the students themselves setting high expectations for their own work and progress. If teachers lead to the top, students will learn to the top and then lead those around them in the same direction. Learning to the top then becomes a natural and embedded process because the students are becoming self-actualised, self-monitoring and self-aware learners who are capable of reaching remarkable heights. Scaffolding and support will be needed along the way as part of the rollercoaster journey that classroom learning represents, but that is something that we, as teachers, are already adept at providing.

Generalising hugely, but not totally inaccurately, in much of our educational provision in recent years we have made advances in our professional skill and understanding of supporting students with learning needs and those at the lower end of the ability spectrum. We are perhaps happiest teaching to the middle or just above the middle of the ability range of the class before us, catering best for the majority (as is reasonable) and occasionally remembering to set some stretch and challenge by way of a worksheet or extra reading for the bright ones. We worry about aiming too high in our own practice and leaving too many floundering in our wake. This is understandable professional caution, and no teacher or institution should be judged harshly for getting a lot right for a lot of pupils a lot of the time.

However, a different approach would benefit all learners. Tom Sherrington’s influential 2012 blog post ‘Gifted and Talented Provision: A Total Philosophy’, was part of my own learning journey in terms of opening up the possibility that setting the bar high for all learners is both appropriate and practical. We are doing no student any favours by excessively simplifying, stripping away and reducing meaningful content to a bare minimum. Subsequently reading no-holds-barred Ofsted reports from 2013 and 2015, now reinforced by Rebecca Montacute’s Sutton Trust report, Potential for Success (2018), has bolstered my thinking: a new approach is not just desirable but absolutely necessary. We are failing many students in our classrooms by not offering them the challenges they need and deserve. We are underestimating what they are capable of, in secondary schools in particular, by failing to build on the progress pupils make at Key Stages 1 and 2. This is a disconnect with significant social implications: the attainment or excellence gap whereby high-attaining children from disadvantaged backgrounds underperform in comparison to their peers is not being addressed. Learning to the top, based on modelling by teaching to the top, can help to address the issue squarely.

Allow me to clarify. Schools have been working hard for years to close the attainment gap between pupil premium students and non-pupil premium students. Likewise, schools have historically concentrated on their GCSE C/D borderline pupils (now levels 4/3) with considerable success. But have schools forgotten to focus on the need to raise standards for all, especially high-attaining pupils? Are teachers and schools afraid to ‘push the top end’ for fear of actually widening the attainment gap? If so, this may not be the right approach. It would be better to raise expectations for all and to bring all pupils to the summit.

4. Lifelong learning

This book unashamedly champions lifelong learning for learning’s sake. Regardless of where individuals start from we can end up in unexpected and glorious places, having got there with the help not only of schools and teachers but also employers, public libraries, universities and many others. An unexpected and glorious place for me when I was starting my own learning journey as a child was Luton Central Library. It was new and big and exciting. I learned the layout, recognised the librarians and, even then, I think I understood something of what it represented and what the people who had built it wanted. I loved it and it really mattered to me. We had no books at home (where the word book meant magazine). Now, I had proper books.

Our journeys should be entirely self-justifying. Art for art’s sake? Absolutely. Learning for its own merits and wider cultural value? In an altruistic society we should expect nothing less. We may need thousands of engineers if our future world is not to fall apart, quite literally, but we also need philosophers, dancers, authors and artists to interpret and reimagine those worlds, crumbling or creatively dynamic as they may turn out to be. We are not so well endowed with riches that we can afford to throw away the potential and capacities of any pupil in our care, because who knows what and how that child will contribute to the future? We can only be certain that they will offer something, so let’s help to make it the best it can be.

That great educational success story of the twentieth century, the Open University, encapsulates this ideal perfectly (its significance is discussed in Chapter 10). Lifelong learning doesn’t have to be this literal, of course, but anything we can do to foster critical, evidence-based thinking in our schools, alongside the acquisition of culturally enriching knowledge and then more knowledge, has to be worthwhile.

5. Able to remarkable

‘It’s not as if we never produce really bright kids, is it? Dr Emma came in the other day to say hello. She told me that Yolanda from her year group is now at university after taking a year out. Just goes to show!’ What does it go to show, exactly? That the school offered an impressive programme of aspiration, stretch and challenge to the one and not the other? Yolanda’s remarkable learning journey reminds us that students develop at different rates, both in terms of their academic attainment and their motivation to succeed. It also tells us that if we get the philosophy right of seeing all students as potentially remarkable and of viewing learning as a process, not an outcome, then we stand more of a chance of seeing Anna’s fine achievement as normal rather than exceptional. Not to mention the equally meritorious successes of Maya retaking her maths GCSE or Tom’s resolute adoption of coping strategies so that his mental health issues do not prevent him even thinking about a higher education course.

The great majority of activities and strategies included in this book are appropriate to all pupils and are not reserved for top sets or high prior attainers. It is hardly my job to tell you what suits your pupils. All I ask is that you keep an open mind as you discuss the approach and strategies in your department or school and consider whether they might work for you. I am taking as an absolute and irrefutable given that you, like every other teacher I have ever met or known, want nothing but the best for your students.

High-attainer provision has to compete for attention with many other major issues facing schools and education, including behaviour management, monitoring pupil premium provision and the attainment/excellence gap, to name but a few. Business seen as more relevant or more urgent trumps it on CPD days and in regular departmental meetings. An elite of high-attaining students can surely look after themselves for another week or term?

However, ‘what aboutism’ is never a strong argument to distract attention away from a central dilemma. The fact that education in the 2020s will face a number of key challenges and problems does not preclude us from asking some tough questions about why the purple prose of our school prospectuses and the anodyne adjectives of our mission statements are not grounded in the everyday reality of setting the bar high for every pupil.

Obstacles to overcome

However, there are significant obstacles in the way of this learning journey.

Firstly, if some official baseline data is to be believed, we are at a very low starting point. ‘Failing’, ‘mediocre’ and ‘depressing’ are not the adjectives we might expect to read about the education of high-attaining pupils in the twenty-first century, but these damning descriptions are taken from recent Ofsted documents on the state of more able provision in English schools. In particular, a report published in 2013, and a follow-up one in 2015, raise serious misgivings about the willingness and ability of some schools to challenge the underperformance of this cohort of children.

I’m going to pick out a few of the main findings of the 2013 report The Most Able Students:Are They Doing As Well As They Should in Our Non-Selective Secondary Schools? ‘Most able’ was defined here (and in the follow-up report) as referring to Year 7 students who had achieved level 5 or above in English and/or maths by the end of Key Stage 2. Some 65% of pupils achieving level 5 in English and maths at primary school did not reach an A* or A grade in both subjects at GCSE and 27% of them did not reach a B grade. In 20% of 1,649 non-selective 11–18 schools, not one student in 2012 achieved A level grades of AAB (Ofsted 2013: 4).

Such was the gravity of the findings that Sir Michael Wilshaw, then chief inspector of schools, felt that they challenged the very principles of comprehensive education:

Too many non-selective schools are failing to nurture scholastic excellence. While the best of these schools provide excellent opportunities, many of our most able students receive mediocre provision. Put simply, they are not doing well enough because their secondary schools fail to challenge and support them sufficiently from the beginning. (Ofsted 2013: 5)

The report’s key findings included:

Schools do not routinely give the same attention to the most able as they do to low-attaining students.Teaching is insufficiently focused on the most able at Key Stage 3: too much work is repetitive and undemanding. Parents and teachers too readily accept underperformance.More able children receiving pupil premium funding lag behind their peers and are less likely either to be entered for the English Baccalaureate or achieve it. Able pupils who qualify for free school meals are particularly overlooked.University entrance is not a sufficient focus for many schools.From over 2,300 lesson observation forms, the most able students in only a fifth of these lessons were supported well or better. In a few schools, the teachers didn’t even know who the most able students were.

In 2015, Ofsted published The Most Able Students: An Update on Progress Since June 2013. Unsurprisingly, the picture had not improved in such a short time. Inspectors reported ‘too much complacency’ in many of the schools they visited, a ‘glass ceiling’ that too few leaders were ambitious enough for their students to smash, and a lack of prioritising for more able students. Unchallenging teaching was too often accompanied by low-level disruption, and there was a failure to provide more able students with the information and guidance to prepare for higher education, especially those from a disadvantaged background. In a monthly commentary in June 2016, Sir Michael Wilshaw was so cross about schools that were failing to meet their responsibilities to ‘thousands of our most able pupils’ that he proposed the return of national testing at Key Stage 3 and even sanctions, such as refusing to allow such schools to become academies.

Hugely important among Ofsted’s findings is that disadvantaged pupils of high ability are consistently failing to make the progress they should from their starting points. This is an urgent issue of social mobility which we cannot ignore. The excellence gap must be tackled.

To add to this gloomy picture, a recent survey of the UK landscape for the education of the most able children by two respected former teachers and current experts in the field, Martin Stephen and Ian Warwick (2015: 6), offers a stark conclusion: ‘The first [conclusion] is that provision for the education of the most able children in the UK is in major crisis, and declining to the level where if it were a species of animal it would be deemed close to extinction.’ They characterise the UK as ‘something of a desert for the teaching of gifted and talented children’ (2015: 29–30), with viable schemes starved of funding and teachers given little training or the means to develop clear careers in this area.

Furthermore, we can’t even agree on our terminology. Are our best students gifted and talented, outstanding, able, more able, high starters or just bright? And do labels matter anyway? It gets worse: we confuse ability and attainment. Oh, and IQ and intelligence. Whatever label a school or college applies, there is a natural tendency to treat high-attaining students as if they somehow just look after themselves emotionally. This is not the case. Many will have well-being issues which require and deserve as much care and attention as those facing other pupils.

Where to start? Heaven knows, we teachers beat ourselves up about everything we cannot do and would like to do, and now there are distinguished commentators telling hard-pressed, under-resourced schools that there is something else that we are getting very wrong indeed. There are 101 sound, structural reasons why provision for what Ofsted terms our more able students is not what it should be, but it is not the purpose of this book to start blaming schools and teachers for everything that has hitherto gone wrong.

Getting the approach right

If we are to address meaningfully the challenges of educating our high-attaining students, let’s put the issue, and the students themselves, centre stage. Treating such provision as a fringe benefit for a lucky few is entirely the wrong approach to take.

If we know at step 1 how to stretch and challenge all our students every day, in every lesson or every sequence of lessons, then we go a long way to moving them all, and not just the elite few, from able to remarkable. Better still, if all our students themselves know how to demand excellence of each other (step 2), then we are even closer to getting the approach right. Something amorphous called ‘good teaching’ or ‘effective teaching’ will always be subjective and hard to pin down. But if we focus instead on how well teaching enables students to make good, effective and sustained progress, and then to behave as expert learners and as exemplars for those around them, we are more likely to have something worthwhile to measure and assess. Adults lead, students learn, students lead.

Of course, some students will always start with more intelligence than others (we will look at the contentious issue of intelligence in more detail in Chapter 1). Some will secure better exam results than others. Some will have stronger language, spatial or movement skills helping them to audition for and secure leading roles in the school play. Some will score more points at basketball than others because they have more fast-twitch muscles and superior gross motor coordination. This is a fact of life that no amount of positive thinking or equality of provision can deny.

Some students will simply be outstanding achievers in everything they do at school. But it is not for us as teachers, parents and educators to put caps and limits on any student. Putting a label on one child and not on another risks doing precisely that – unless our schools implement policies and practices which mean that, in effect, such labels are just a convenient, temporary shorthand and not a guarantee of anything.

I’m ready to start this learning journey – give me solutions, not problems!

Reassuringly, there is plenty to suggest that if we accept and address some of these issues, the steps we can put in place to modify and improve our daily practice are modest, attainable and will produce results. To nourish us on our way we can draw on the research evidence of, for example, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Dylan Wiliam and Daniel Willingham and access the websites and recommended further reading of the Education Endowment Foundation (https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk) and the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University led by Rob Coe (www.cem.org). Alongside this, we can implement the countless good practices currently adopted by many schools across the country. There is no need to reinvent the process of making fire because already in many schools the logs are glowing, the results are warming, and schools and teachers are happy to share their firesides. TeachMeets are integral to this. Even that once unwelcome visitor to the hearth, Ofsted, is happy to offer examples of observed good practice and pupil achievements, and surely deserves to warm its hands with us and contribute to a very necessary dialogue.

Meet your five expert learners

Anna and Tom sit in the middle of the ability rankings when they join your school in Year 7, although Tom’s difficult home life has already been flagged up as a pastoral concern. Slightly below them in attainment sits Maya, who is thought to have plenty of potential by her feeder school but is lacking in motivation. Asif is a high attainer with sufficiently strong SATs scores in English and maths for him to join your high-attainer programme. You are aware from a primary school visit that Yolanda is another pupil of great potential.

Your students are not ‘typical’, and nor are mine. They have one shot at secondary education, so they and their parents/carers would like your school to do your best by them, offering as much stretch and challenge in as many areas of the curriculum as possible. As Christine Counsell recently reminded us, the origin of the word ‘curriculum’ lies in the Latin verb ‘currere’, to run; she brilliantly defines curriculum as ‘content structured as narrative over time’ (Counsell 2018; original emphasis). Your runners and my runners need to finish, but they’re not in a race – still less one which only rewards the first over the line. The aim is for each of them to achieve the best of which they are capable, whether they leave the starting line with prior training and genetic advantages or little experience of, or appetite for, running. Nor does the finishing line represent GCSEs or BTECs: it recedes as learning becomes lifelong. The narrative of the run will embrace ebbs and flows, ups and downs because it is more cross-country than track: runners can be pacemakers for others and help each other. The progress of our five expert learners will not be linear. What we may term their ‘interim outcomes’ as they hit one checkpoint – namely, the exam results they achieve and what they do upon leaving school at 16 or 18 – may be surprising.

This curriculum matters because its success or failure in supporting all our learners can be measured both across time among the peers and contemporaries of our five expert learners as they experience it from week to week, but also over time as students continue on their lifelong journeys. The significance of a curriculum which builds understanding via knowledge and skills in both dimensions can hardly be overstated.

What we will never find on our journey, of course, is a magic bullet or simple answer. Brain Gym won’t do it. Yes, I sat through those sessions too. I was there for key skills and have the blister from rewriting every scheme of work. Finding every student’s unique learning style won’t address it – yikes, no. There are still posters of Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats on the walls of a department at my school. Those books were a cult back in the 1970s and must have sold millions. If the posters are just being used in light-hearted fashion to stimulate creativity in a lesson, then fair enough. But if any teacher can demonstrate that any of these methods produces a verifiable positive difference in learner outcomes, then I raise all of my thinking hats to them and will spend my next CPD session under an energy pyramid, stroking my black cat and reading my horoscope. Growth mindset has been seized upon by some with a fervour matched only by its detractors’ gleeful criticisms. Even Carol Dweck herself has reservations regarding teachers who have adopted ideas that she never intended to apply in schools, and about which she professes little expertise.

As teachers we are as vulnerable as Year 7s to the new fidget spinner fad of the staffroom. What will it be this time: exit tickets? Pose-pause-pounce-bounce questioning? Visual, auditory and kinaesthetic learning styles (VAK)? Feedback? (It’s got to be feedback – it always is!) The twin volcanoes of Twitter and educational research emit a lava flow of all-consuming intensity, so surely we can identify some riches among the fire and rubble? All these trends and fads can have the effect of leaving us jaded and judgemental, sticking to what we know for our bright ones. After all, it works for us, doesn’t it – at least for some of our students, some of the time?

This can lead to what seems to be a logical position – namely, looking to other countries to see what works there and to recommend its introduction here. Every year we hear siren calls from commentators and journalists to look to the educational equivalent of the World Cup, PISA rankings, and to follow their lead to Scandinavia or South-East Asia. Whatever we are doing is flawed, and we can surely learn from these clever lands?

Forget Finland. With all due respect to Finnish educationalists, and the admirable education systems of other countries, what works for them will not necessarily work for us. Their achievements reflect structural measures introduced a generation or so ago, perhaps longer, because lasting change in education takes decades not months. Holiday anecdote is no match for peer-reviewed educational research worthy of the name. If we are to address the low starting points acknowledged by Ofsted and others, then solutions must be found in Teignmouth and Tynemouth, not TripAdvisor.

Read ‘Rotherham’ (Ryan 2018). Will Ryan’s essay describes his recent journey to one of the country’s most disadvantaged towns to trace the legacy of a man called Sir Alec Clegg, chief education officer for the West Riding until 1974. Clegg championed an ‘ethic of excellence’ in Rotherham’s primary schools which was rooted in the local environment and in a sense of awe and wonder. At Thornhill and Ferham, Meadowview and Canklow, Ryan finds evidence of success in so many areas – from pupil values and sports to music and art to head teacher leadership and reducing teacher workload – all achieved against a backdrop of one of the most deprived communities in the country. His anecdotal evidence is corroborated by Ofsted. Solutions and inspirations may be closer than we think.

This book aims to offer a pathway for our learning journey through the gorse bushes of gifted, the underpasses of underachievement and the roadblocks to remarkable. Can we produce more students who are not just able but remarkable? Not just high-attaining but the highest attaining possible? Not just very good students but expert learners? I believe not only that we can but we must. On the one hand, we have to be aware of the demands of the society in which we live for more engineers, computer coders, nurses, entrepreneurs and app designers. If there is a chance for today’s schools to produce another J. K. Rowling, Mary Beard or Tim Hadfield, let’s not waste any more time. If that utilitarian motive is not sufficient – and it really isn’t because we can’t have much of a clue about the future needs of society and tend to get it horribly wrong when we try – then we can legitimately argue that helping to get the very best out of all our students is surely worth the effort as an aim in its own right, whatever the outcomes. That is what most of us came into teaching to achieve. Like politicians, we want to make a difference; unlike many of them, we really mean it. Learning matters for its own sake, not for Ofsted and not for an academy leadership team.

The message of this book should be an obvious and reassuring one: if something works with high-attaining pupils then it will work with all pupils. You do not need to find horcruxes amid the deathly hallows of learning and teaching before you can destroy the Voldemort of underachievement. No box of delights, no glowing magic key, no wizardry is needed. If you have robust, triangulated evidence that what you are doing currently offers best practice for your classes, then those good habits and practices will work for your brightest pupils. Conversely, there is no amount of self-delusion that a scheme of work currently aimed at somewhere in the middle of an attainment range will interest and stimulate those pupils – still less their high-attaining peers – to ask big, interesting questions or to make an unexpected connection. You are a teacher, not a magus. A trained and experienced professional, not a charlatan. Your pupils are typical, not geniuses. Spoiler alert: geniuses don’t exist.

Here is my approach:

Make every lesson as stimulating and interesting as possible for as many students as possible as often as it can possibly be achieved in a sequence of lessons. Teach to the top – scaffold and support all students as necessary. Model these attitudes and activities so they become second nature to students who can then carry on the modelling themselves. Effective curriculum mapping is essential both within and between subjects to avoid repetition of content and approaches.Treat all pupils as if they are capable of high attainment from the minute they walk into your classroom. Offer them all, without exception, opportunities to thrive and excel in drama, music, design technology, chess, Raspberry Pi and whatever the pupils themselves can offer each other and whatever your staff can offer. The ones who are currently high-attaining students may be among the first to take advantage, but they will not be the last once the word gets around: you will benefit from a changing cohort of interested and interesting pupils. Set the bar high and don’t let it clatter to the ground when it’s knocked off – just put it back.Offer the best enrichment programme, personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) programme and extra-curricular opportunities you can, ideally with student input into what is created and how it is delivered and offered. Complementary curriculum design which recognises tangents and crossovers is surely, at least in part, the province of experts – namely, the students who experience it every day and can identify and isolate the fertile and the fallow.Retrace your steps for a moment

Please go back to the list of qualities you noted for your outstanding students at the start of this chapter – you might have thought of a few more. Now think of a student or a class which you are convinced does not at first sight share these attributes. Are you sure? Have you observed them as part of a stage crew, playing basketball or tackling a sonnet? Have you done a ‘pupil pursuit’ and observed that student/class in the round during a school day (let alone a week)?

Perhaps I am guilty of motherhood and apple pie naivety, but so often when we literally move outside our classroom and look at the same pupils elsewhere, we see evidence of qualities and abilities not apparent when they are with us, for any one of a thousand reasons. But this does not mean that those attributes are not there in some part of a busy school week or outside school time.

My argument is that these remarkabilities are there, latent and dormant, in many more students than we might at first acknowledge. Anna and Asif may be unaware of what they can do or may be unwilling to acknowledge it – again, for many different reasons. Yolanda may be further along the route as a high prior attainer, with clear academic successes behind her at Key Stage 2, but she too has not yet reached her destination. It’s our job to bring these qualities to the surface within all our learners for the benefit of the whole school community. Maya and Tom know all about resilience and determination because they’ve been attending Scouts and they’ve both played football matches after school. But Tom’s home life has been challenging of late and Maya has been in with a group of girls who have never seen the point of trying too hard in lessons. Helping all these students to create mental models of success for themselves will be part of their learning journeys. This will be made easier because they have shown the ability to do it already. We can help them to apply the deliberate, purposeful practice of hockey to history or from Scouts to science to encourage them to make themselves into remarkable lifelong learners.

Don’t take my word for it:

Dismantling students’ own modest perceptions of what they can attain seems to me one of the most important priorities for classroom teachers. If we can set the level of challenge at a high level early in our students’ secondary career, the better equipped they will be to tackle the increasing demands of GCSE and A Level. (Tomsett 2016)

This quotation from a characteristically personal and engaging blog post by teacher and head teacher John Tomsett strikes the key note. Teaching Macbeth to a Year 7 class of thirty, none of whom has ever learned Shakespeare previously? Of course it’s possible. Writing paragraphs of literary criticism using a point-evidence-analysis model? Yes we can, because Sir modelled it for us. Tomsett’s approach created challenges for some learners who found the work hard, but he turned this to collective advantage by encouraging creative outcomes in the form of a sketch or a story on a class blog. Completing a full circle of benefits, parents heard some of their children’s literary analysis at a subsequent parents’ evening. This approach to mixed-ability teaching is unashamedly demanding and complex, but ultimately it is much more respectful of potential than many curriculum models based on setting and prior assessment data. Great material, a humane and flexible approach, uncompromisingly high standards and clear goals led to measurable progress and worthwhile outcomes.

Alongside the gauntlet thrown down by Tomsett to unpack students’ own, often poor and limited, perceptions of themselves as potential learners comes another glove from me to make the pair. Some of the biggest obstacles to raising student attainment come from teachers, unwittingly and unconsciously. We don’t provide sufficient challenge to our classes sufficiently often. We mistake noisy group work (or less often its opposite – a calm and quiet classroom) for purposeful activity. We cover a scheme of work and there is lots of green ink on books for the next work scrutiny. These and many other poor proxies for learning and student progress are the tripwires I negotiate every day, dodging a few and falling over others.

If, on a national scale, we are seriously failing to educate our high-attaining pupils in the numbers and to the standards that we should be – and as evidence suggests we are – then we, as teachers, the adults in the rooms, need to think carefully about why that is. For therein lies at least part of the solution. In subsequent chapters, I will be discussing activities designed to encourage students to think hard by leading them, or better still getting them to take themselves, into their ‘struggle zones’.