24,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'A penetrating account of Cuban history ... [an] extraordinary book' MADELEINE K. ALBRIGHT, US Secretary of State, 1997-2001 'This is a splendid book, which narrates the tragedy of a Cuban, Oswaldo Payá, who dared to oppose Fidel Castro in communist Cuba, and paid dearly for it. David E. Hoffman's research is magnificent and his biography reads like a great novel' MARIO VARGAS LLOSA The riveting biography of a dissident who defied Castro's dictatorship, and paid with his life. Oswaldo Payá was seven years old when Fidel Castro seized power, promising to create a 'free, democratic, and just Cuba'. But Castro instead created an authoritarian regime and crushed all dissent. The dream of democracy became Payá's life work. Sent to Castro's forced labour camps, he could not stay silent, and formed a pro-democracy movement. After receiving multiple death threats, Payá was killed in a suspicious car accident in 2012. Democracy is in retreat all over the world. Oswaldo Payá showed how to fight for it. His battle was waged from the streets of Havana but carried universal truths.Pulitzer Prize-winner David E. Hoffman, author of the acclaimed The Billion Dollar Spy, tells the compelling story of a courageous dissident in action.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

i

Praise for Give Me Liberty

‘This is a splendid book, recounting the tragedy of a Cuban, Oswaldo Payá, who dared to oppose Fidel Castro in communist Cuba, and paid dearly for it. David E. Hoffman’s research is magnificent and his biography reads like a great novel.’

Mario Vargas Llosa, Winner of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature

‘David Hoffman has written a penetrating account of Cuban history, highlighting the true nature of the Castro regime and the courage of one man who became a threat to it. Through this extraordinary book, the world can now learn the story of Oswaldo Payá and understand why my friend Vaclav Havel nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize.’

Madeleine K. Albright, United States Secretary of State, 1997–2001

‘David Hoffman’s Give Me Liberty is a superbly readable and thoroughly researched account of attempts from within Cuba to democratise its highly authoritarian system. It is also a moving and convincing tribute to the courage and tenacity of Oswaldo Payá who was convinced that fundamental political change must come from within Cuba rather than from Washington or Miami.’

Archie Brown, Emeritus Professor of Politics at Oxford and author of The Rise and Fall of Communism

‘With his signature flair for joining white-knuckle narrative to meticulous journalism, Hoffman brings us a ground-breaking biography. Hoffman’s portrait of Oswaldo Payá offers a sweeping panorama of Castro’s Cuba, from its glimmers of promise to its devastating plunge into authoritarianism.’

Marie Arana, author of Bolívar: American Liberator and Silver, Sword, and Stone: Three Crucibles in the Latin American Story

‘This blend of biography and history has the intrigue and surprise of a well-written spy novel.’

Booklist

‘[F]inely detailed … A welcome study of political resistance by figures unknown to most readers outside Cuba.’

Kirkus

‘[A]n engrossing history of modern Cuba … an intriguing and often inspiring look at the courage of one man’s convictions.’

Publishers Weekly

ii

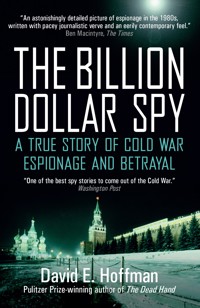

Praise for The Billion Dollar Spy

‘An astonishingly detailed picture of espionage in the 1980s, written with pacey journalistic verve and an eerily contemporary feel. Essential reading for anyone who wants to know how the spy mind works.’

Ben Macinytre, The Times

‘It is the human factor that elevates The Billion Dollar Spy to a different level: non-fiction as rich and resonant as a spy novel by John Le Carré or Graham Greene.’

Mail on Sunday

‘The Billion Dollar Spy is one of the best spy stories to come out of the Cold War and all the more riveting … for being true. It hits the sweet spot between page-turning thriller and solidly researched history … and then becomes something more, a shrewd character study of spies and the spies who run them, the mixed motives, the risks … This is a terrific book.’

Washington Post

‘The Billion Dollar Spy reads like the very best spy fiction yet is meticulously drawn from real life. It is a gripping story of courage, professionalism, and betrayal in the secret world.’

Rodric Braithwaite, British Ambassador in Moscow, 1988–92

‘A fabulous read that also provides chilling insights into the Cold War spy game between Washington and Moscow that has erupted anew under Vladimir Putin … It is also an evocative portrait of everyday life in the crumbling Soviet Union and a meticulously researched guide to CIA sources and methods. I devoured every word, including the footnotes.’

Michael Dobbs, author of One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War

‘A true-life tale so gripping at times it reads like spy fiction.’

Los Angeles Times

‘Hoffman excels at conveying both the tradecraft and the human vulnerabilities involved in spying.’

The New Yorker

iii

Praise for The Dead Hand

‘A stunning feat of research and narrative. Terrifying.’

John le Carré

‘Authoritative and chilling … a readable, many-tentacled account of the decades-long military standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union … The Dead Hand is deadly serious, but this story can verge on pitch-black comedy – Dr Strangelove as updated by the Coen Brothers.’

New York Times

‘The Dead Hand is a brilliant work of history, a richly detailed, gripping tale that takes us inside the Cold War arms race as no other book has … a story so riveting and scary that you feel like you are reading a fictional thriller.’

Rajiv Chandrasekaran, author of Imperial Life in the Emerald City

‘[M]agisterial, human, vividly readable’

Peter Preston, The Guardian

‘[Hoffman] has compiled a fascinating narrative of the last phase of the cold war and the era of Mikhail Gorbachev, glasnost and perestroika, which ended amid the collapse of the Soviet Union.’

Max Hastings, Sunday Times

‘[The Dead Hand] has important things to say … It is exceptionally well informed. Anyone interested in the Cold War will learn something new from this fascinating, if rather depressing, read.’

BBC History Magazine

‘If you like your history told James Bond style, you’ll love this book.’

Simon Heffer, Daily Telegraph

iv

v

GIVE ME LIBERTY

OSWALDO PAYÁ AND THE STRUGGLE TO FREE CUBA

DAVID E. HOFFMAN

vii

To Carole

viii

Contents

xi

We can’t be just the spectators of our own history. We must be the protagonists.

Oswaldo Payá, Pueblo de Dios, No. 7 1987

xii

Prologue

HAVANA, JULY 22, 2012

Bleary-eyed, Oswaldo Payá had been up all night, waiting for his daughter to come home. Rosa María was twenty-three years old, a university graduate in physics, lively and strikingly attractive, with a rebellious streak very much like her father. That she had been out all night, Oswaldo could do nothing, but he waited for her, worried about her safety, agitated, unable to sleep. She had promised to join him before dawn for the long and dangerous journey, staying one step ahead of state security.

Where was she?

Oswaldo was sixty years old, with thick, wavy hair the color of charcoal and a swirl at the peak of his forehead. He had deep rings under his eyes and worry creases sometimes rippled across his brow, but his brown eyes were soft, understanding, and patient. Oswaldo dressed casually, in jeans and a short-sleeved checkered shirt, the collar open wide, his shirt buttons absentmindedly askew. His voice had a slight nasal tone. He was a practiced orator, clear and articulate. He had a lot to say, and did.

By day, Oswaldo was an engineer who specialized in medical electronics, troubleshooting life-saving equipment at Havana hospitals. He worked with oxygen tanks, ventilators, and incubators. He took great satisfaction when he could help save a life.xiv

But his great passion was to change Cuba, to unleash a society of free people with unfettered rights to speak and act as they wished. He called it liberation. He had devoted many years to the cause, shared with his wife, Ofelia Acevedo. At this moment she was away, visiting her parents, but she knew he was taking another step into the unknown. She sensed he was rushing toward something. She wondered why he was taking the chances, hurtling into the darkness once again.

Ofelia and Oswaldo had made a promise to themselves as newlyweds years before: their children would live in a free country. They would fight for it and never flee Cuba. Oswaldo had spoken out against Fidel Castro’s despotism since his own days in high school. He wrote dozens of manifestos and declarations, published underground handbills, formed a prodemocracy movement, and championed the Varela Project, a citizen initiative demanding free speech, a free press, freedom of association, freedom of belief, private enterprise, free elections, and freedom for political prisoners. He had never run from his values.

But lately, fear was choking him. The secret police, Seguridad del Estado, or state security, threatened his family. In fleeting encounters on the street, strangers came up to him and said simply, “Be careful, or your children could be hurt.” Oswaldo knew that state security could cause an accident, a bicycle run off the road, or a careless driver running a red light. They could plant drugs in a boy’s backpack, then haul him off to prison. They could detain and sexually assault a young girl. They could do anything. The thoughts were unbearable.

Oswaldo, shaken, had taken his three children, Oswaldito, Rosa María, and Reinaldo, to a convent of the Sisters of Mary Magdalene near their home in Havana. With assistance from the nuns, he showed them a hidden entrance leading to a concealed room. This was their refuge, he said; if he were ever arrested or if they were in serious trouble, they should come here, and the nuns would harbor them. The children thought it was a lark, but Oswaldo was serious. Another time, he turned to a visitor from Sweden and asked point-blank: What would it take to get asylum for my family?

Finally, in desperation, Oswaldo and Ofelia made a tough decision. xvThe time had come to send their children out of Cuba. The two oldest, Oswaldito and Rosa María, applied for and were admitted to the University of Amsterdam. They were to go in August. The youngest, Reinaldo, might go to Spain. It was agonizing for Oswaldo and Ofelia to think about being apart from their children, to abandon the vow they had made to build a free country for them, but they felt they no longer had a choice. They sensed the dangers were growing.

Where was Rosa María?

Oswaldo was heading to Santiago de Cuba, 540 miles to the east, to train young activists and organize local committees for the Movimiento Cristiano Liberación, the democracy movement he founded nearly twenty-four years earlier. He started it with friends in the parish of El Salvador del Mundo in Havana, where four generations of his family had anchored their Catholic faith. The movimiento had grown to more than a thousand members across the island, a civic and political movement, nondenominational but driven by the values of Christian democracy that had confronted fascism and communism in the twentieth century.

At this point, Fidel, almost eighty-six years old, had relinquished power to his brother Raúl, who eased up slightly on the economy but maintained a hard line against any dissent, continuing the Castro dictatorship of more than five decades. Members of the movimiento were frequently jailed, harassed, interrogated, and pressured to become informers. State security kept Oswaldo under surveillance, and his name was blacklisted. He could not travel by plane, train, or bus without being immediately spotted. The trip to Santiago de Cuba would set off alarms if he took public transportation. Yet, from years of experience, Oswaldo had developed a clandestine method to evade surveillance. He could move relatively unseen in a rental car driven by tourists. State security might spend a few fruitless days looking for him. In this case, the “tourists” were two young men, from Spain and Sweden, both eager democracy activists who had arrived in Havana two days before.

The only problem was that they arrived unexpectedly early, and now he had to rush the trip, which had been planned for later. On July 26, in four days’ time, a holiday marked the anniversary of Fidel’s 1953 attack xvion the Moncada army barracks in Santiago de Cuba, the first armed assault of his guerrilla war. State security was on alert. To reach Santiago, a day’s drive, and get back, Oswaldo would have to hurry. He decided to leave before dawn, while darkness cloaked the streets.

Just before 6:00 a.m., Rosa María cracked open the front door.

Oswaldo was waiting in their tidy living room, with pale yellow walls and black-and-white checkered floor tiles. Rosa María steeled herself for his reproach. But as soon as he saw her, his anger melted away. She was safe. There was no time for questions. He had to leave before the sun rose. She had planned to go with him but was exhausted. She didn’t dare ask him to wait for her. She knew he couldn’t.

Oswaldo crossed the room and kissed her good-bye.

He grabbed his backpack. He motioned to Harold Cepero to grab his own overnight bag. Cepero was Oswaldo’s protégé. While waiting for Rosa María, Oswaldo had spent the night talking with Harold about God, Cuba, democracy, and dictatorship. Oswaldo ranged over these topics naturally and passionately. With boyish good looks, tousled hair, faded jeans, and a white T-shirt, Cepero, thirty-two years old, was Oswaldo’s hope for a new generation of activists. He was helping Oswaldo train young people to fight for their rights, and he and Rosa María were preparing a youth magazine. The first edition was almost ready. As Harold stepped toward the door, Rosa María rushed up to him and put her hand on his shoulder.

“Be careful,” she admonished him. Cepero flashed back his wide, generous smile.

Oswaldo opened the front door of 221 Calle Peñón and cautiously stepped into the predawn darkness.

The air was pleasant and the skies clear. To his left he could see the knurled boughs of the old álamo trees that shaded his childhood playground, Parque Manila. The house where he had grown up, at 276 Calle Peñón, was directly across from the park. The house was a boxy two-floor structure of sun-washed masonry, with an oversized portico thrusting out toward the curb. Oswaldo was the fifth of seven children, and when he was a boy, the park was his second home. Next door, at 280 xviiCalle Peñón, stood a similar but smaller house where Oswaldo’s aunt Beba lived. She was his father’s sister, with no children of her own. For as long as Oswaldo could remember, Beba was a presence in his family, often walking him and his brothers and sisters to Sunday Mass or taking them by the hand to the movies.

In recent years, Beba helped him once again. Her house became the nerve center for his ambitious and daring political quest.

Oswaldo turned to the right, away from the park. He and Cepero walked silently down the slope of Calle Peñón, past slumbering households, with dogs and roosters milling about behind gates and fences. Oswaldo looked warily for any cars in the shadows. Over many years, state security stationed their surveillance vehicles near the park, and they paid informers in nearby houses to keep an eye on him. Oswaldo hoped the darkness would cover their departure, giving them a head start.

El Cerro was once a neighborhood of luxury villas built in the 1800s by the upper classes seeking to escape Old Havana. Back then it was a refuge of spacious homes, with perfumed flowers and flickering gas lanterns. Even today, remnants of that era were visible on Calle Peñón: balconies of elegant stone balusters, decorative archways, and elaborate cornices along the rooftops. But over the decades, El Cerro slowly crumbled; concrete exteriors turned dingy, and once-breezy open windows were now shuttered behind rusty iron grates.

Oswaldo passed a forbidding, tall cinder-block wall. Six years earlier, the regime had painted a threatening slogan. “In a besieged fortress,” it declared, “dissidence is treason.”

A few blocks beyond, they reached the Calzada del Cerro, on most days a busy avenue. Now it was quiet. Oswaldo could barely make out the graceful colonnades that flanked the street, faint reminders of the city’s lost grandeur. Just around a corner, a block off the Calzada, stood the parish church with a bell tower that was at the center of Oswaldo’s faith. But it was not the church or the colonnade that commanded his attention.

He peered into the shadows, looking for a rental car.

• • •

xviiiAt 6:15 a.m., a blue Hyundai Accent pulled up to the curb. Oswaldo recited a brief prayer, softly but audibly, and climbed into the rear seat on the driver’s side. Harold climbed in the back on the passenger side. Two foreigners were in the front. Oswaldo had met them two days earlier. The driver, Ángel Carromero, twenty-six, led the Madrid youth wing of Spain’s ruling Partido Popular, or People’s Party. Next to him was Aron Modig, twenty-seven, who headed the youth organization of Sweden’s Christian Democrats in Stockholm. They had come to Cuba expressly to assist Oswaldo, and rented the blue Hyundai to drive him around, evading state security.

Carromero was in flip-flops. Modig wore a T-shirt with navy and white stripes, and blue shorts. Their trip had been arranged somewhat hastily. Both knew the risks of the long drive, and Carromero was nervous about it, but they were eager to prove useful.

Oswaldo gave directions out of Havana toward the east, and onto the ocho vías, a broad eight-lane highway, almost empty at this hour. Carromero glanced at the rearview mirror and saw no one trailing them. Soon the sun was up and the road straight and wide.

Oswaldo talked for a long time, never tiring, full of memories and pent-up hopes, a lifetime of visions pursued and yet never quite fulfilled. As a boy he had witnessed the seizure of his father’s business as Castro’s revolution confiscated private enterprises in 1965. As a teenager he had protested the crushing of the Prague Spring with Soviet tanks in 1968 and was sent to Castro’s forced labor camps. Later, as a member of the laity, Oswaldo demanded that Catholic Church leaders stand up for human rights and democracy, but, weakened by decades of repression, they chose reconciliation rather than confrontation. When Oswaldo published a popular newsletter, full of his essays demanding basic rights for the Cuban people, the archbishop insisted that he stop. He could not. By the 1990s, when Cubans were plunged into economic despair with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Oswaldo had become a prominent voice of the opposition.

As Oswaldo talked, the sun rose higher and they rolled down the windows. The morning air was already warm and fragrant.xix

Oswaldo recalled how they had launched the Varela Project, challenging Castro’s dictatorship with a citizen petition for democracy. The project was named after Félix Varela, a nineteenth-century priest, philosopher, and Cuba’s most illustrious educator. Oswaldo loved to recount how the movimiento had doggedly collected the signatures, door to door, over four years, then surprised Fidel and state security by submitting 11,020 signatures to the National Assembly in 2002, and another 14,384 signatures the following year. More than 10,000 additional signatures were still hidden by the nuns. Nothing like it had ever happened before in Cuba.

But Oswaldo and his movement paid a heavy price. He was thrust into the crosshairs of state security, a hardened secret police who were trained in the methods of East Germany’s Ministry of State Security, the Stasi. In Cuba, state security harassed and intimidated dissidents and opposition figures using wiretapping, subversion, threats, detention, and fear. Payá took the brunt of it for years. After the first wave of Varela Project signatures were submitted, state security arrested and imprisoned seventy-five of his movimiento activists and independent journalists. They were given prison terms of up to twenty-eight years for nothing more than collecting signatures. Oswaldo was not arrested, but subjected to a different torment, a relentless psychological warfare. The threats he dreaded most were conveyed in exactly the same words, “You will not outlive Fidel.”

When a US diplomat visited his house on Calle Peñón, Oswaldo was insistent. “People aren’t taking seriously enough the threat that they’d liquidate me,” he said.

He confided to a friend, “I see very few chances of getting out alive.”

As Payá and the young activists drove deeper into the Cuban countryside, few cars were on the road, only people riding bicycles, and occasionally a horse-drawn cart. Oswaldo told the visitors about the hardships of day-to-day life on the island. Sugar and tobacco production—once mainstays of the economy—were lower than in the 1950s. Since 2010, Raúl had allowed a nascent private sector to grow, but for most of Cuba’s xxeleven million people, living conditions were dire, salaries paltry, food and goods scarce.

Several hours into their trip, Carromero, the driver, noticed something. A car was following them, far behind, but steadily.

Anxious, Carromero started smoking, holding the cigarette between his fingers at the open window. A red Lada, the Soviet-era boxy auto fashioned after the Fiat, was on their tail, but still distant. The road was getting worse, and Carromero slowed. Carromero mentioned the red Lada to Oswaldo, who told him, “Do not give them any reason to stop us.”

Carromero asked Oswaldo whether it was normal to be followed in such a remote place. Yes, Oswaldo replied. But he urged Carromero to remain calm. The tone of his voice was reassuring. He said that state security often did this to show who was boss, “Don’t forget, we are here.” They wanted everyone to live in fear.

Carromero pulled over for gas. The station was painted in a candy-red and white, with a sign, “Black Gold Servicecenter Sputnik.” It added, “Welcome to Camagüey,” a major city in central Cuba. They had been driving for five hours. Modig, who had been dozing in the car, snapped a photo of Cepero and the gas station at 11:09 a.m. The red Lada stopped too, and the driver eyed them from afar. Carromero looked back, uneasy.

On the road again, as they headed southeast, the red Lada peeled away. At midday they found a place for lunch, another gas station with a bar. They were hungry and wolfed down ham and cheese sandwiches. A boy was selling music CDs. Cepero bought two: one was a compilation of the Beatles, the other a Cuban artist.

Back on the road, a hot breeze rushed through the car windows. Oswaldo pointed out swaths of uncultivated land, fertile fields once devoted to sugarcane, now overrun by the invasive marabú, or sickle bush.

Carromero slipped the Beatles CD into the slot and turned up the volume. Oswaldo loved the Beatles. There were many hit songs on the disc, and he knew the lyrics. He was particularly fond of the Abbey Road classic “Oh! Darling.”

The Cuban countryside rolled by, scenes of hay and grassland.xxi

The music and warm air lulled Modig to sleep again, while Payá and Cepero sang their hearts out.

Then Carromero noticed something in the mirror.

Another car was tailing them, newer than the red Lada, and it was closing in, stubbornly. Carromero saw two men in the car.

Payá and Cepero turned around, too. “The Communists,” Cepero said with a tone of scorn, referring to state security. The car license plate was blue, a government vehicle. Carromero asked what he should do.

Payá responded once again, Don’t give them any reason to stop us. Just keep going.

The car drew closer. Carromero could see the eyes of the driver.

The other car seemed to leap forward. It charged at the Hyundai.

Carromero felt a powerful shudder. He heard a dry, metallic sound. Both cars were traveling in the same direction, so it wasn’t a collision, but Carromero felt the shove.

He lost control of the Hyundai.

Modig had been dozing but suddenly awoke. He curled his legs up in a protective fetal position.

Oswaldo Payá was born ten days before Fulgencio Batista seized power in Cuba on March 10, 1952, establishing a brutish autocracy. Oswaldo was nearly seven years old when Fidel Castro ousted Batista. From his guerrilla outpost in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Fidel had once promised, “We are fighting for the beautiful ideal of a free, democratic, and just Cuba. We want elections, but with one condition: truly free, democratic, and impartial elections.” But once in power, Castro built a dictatorship based on an overarching ideology, a single party, a secret police, total control of communications, and the elimination of civil society. His ambitions were totalitarian, to corral all of Cuba inside his revolution; as he put it, “within the Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing.” Still, the revolution was not airtight. Despite the police state, freethinking bubbled up from the grassroots, especially in the 1990s, when the loss of subsidies from the Soviet Union led to hardship and misery, unleashing waves of discontent.xxii

Oswaldo devoted a lifetime to opposing Castro’s repression. Oswaldo believed the rights of every person are God-given and cannot be taken away by the state. Yet for most of his life in Cuba, those rights were stolen, tarnished, and denied. Even something as innocent as hanging a “Feliz Navidad,” or Merry Christmas, sign on the bell tower of his church was considered subversive. Defiant, Oswaldo hung the sign anyway. He never lived in a state of liberty, but liberty lived in his mind and drove his fight for it.

His most daring challenge to Castro was the Varela Project, a citizen petition printed on a single sheet of paper creased at the half fold. At the top were five demands for freedom and democracy. Those who signed their names also gave their addresses and identification numbers. They stood up to be counted. Oswaldo had no modern tools of communication to mobilize the Cuban people—he had no access to radio, television, or print, and the online world barely existed—yet he was joined by tens of thousands of people demanding the right to choose their own destiny.

The Varela Project should have triggered action by the National Assembly, a referendum, a free and fair election, and a chance at a new, democratic Cuba. But Fidel Castro held a monopoly on power and was intolerant of any challenge to his authority. He ignored the petitions.

However, Castro could not extinguish the spirit of the Varela Project. When massive anti-government protests broke out in Cuba on July 11, 2021, some demonstrators raised their thumb and forefinger in Oswaldo’s familiar “L” for liberación. Nearly all those who spontaneously crowded the streets that day shouted the same demands for ¡libertad! that Oswaldo had championed two decades before. Many still remembered how Oswaldo had braved persecution and death threats, how he had urged them to overcome their fears.

Significantly, Oswaldo’s quest grew from the soil of Cuba. The Varela Project was based on Cuba’s existing constitution and had its roots in the nation’s greatest democratic experiment, the 1940 constitution and the years that followed it. With nothing more than pen and paper, Cubans took the risks to sign and collect the Varela Project petitions. It was not a product of the Miami exiles or the US government, so often xxiiireviled by Castro as the enemy. When some of Oswaldo’s relatives urged him to depart for Florida during the 1980 Mariel boatlift, he refused. “I believed for this entire time that Cuba had to be liberated from within,” he insisted. The Varela Project was that cry from within.

How do people gain the right to think and speak freely, advocate their views, follow their conscience, worship or assemble as they desire—without persecution? How do they secure the right to choose their leaders and set the course for their own future? What does it take to attain such freedoms? These questions are at the heart of this book, the story of one man’s journey into the whirlwind of dictatorship.

Oswaldo did not want to be called a dissident. He thought it applied to those who had once been inside Castro’s revolution and then turned against it. Oswaldo never set foot inside, not from the day he was born. He preferred to be called opposition. He fought a lifelong challenge to a relentless and repressive machine. This book explores where he found the ideas and inspiration, the courage, faith, and persistence against impossible odds.

Throughout Cuba’s volatile history, people rose to demand the right to rule themselves freely. A thread of tragedy and loss runs through their struggle. They were dreamers who dared wish for more, whose visions were cut short, whose pursuit of liberty was lost, then resurrected again by a new generation. Oswaldo Payá inherited these dreams, and turned them into action.

To understand Oswaldo’s life and his quest, it is necessary to begin in the first half of the twentieth century, when Cuba was newly independent from Spain. Liberty did not come easily. Political corruption and violence took a toll. The United States cast a long imperial shadow. But in 1940, the Cuban Republic surmounted its difficulties and gave birth to a new, democratic constitution. It was the work of many, but especially Gustavo Gutiérrez, a jurist, politician, and thinker who harbored a vision of Cuba as a modern republic built on democratic values and constitutional rule.

The vision did not last. The 1940 constitution was later torn up. Dictatorship prevailed.

But Gutiérrez had planted a seed.xxiv

PART I

SEARCH FOR LIBERTY

2

ONE

AGONY OF THE REPUBLIC

The man of law rose in the temple of law.

Gustavo Gutiérrez wore a tropical suit of white linen, known as the dril cien, stylish and cool in the summer heat. He stood at a mahogany desk trimmed in bronze on the floor of Cuba’s House of Representatives. At forty-five years old, Gustavo’s black hair was already receding from a broad forehead. He had brown eyes and a penetrating gaze under thick, dark brows that curved in large arcs. Six feet tall, with an athletic build, he was stern and reserved, a member of the House, a politician, and a lawyer. He was an imposing figure, impatient with those who dithered, “black and white in speech and action,” recalled his eldest daughter. He disliked the boisterousness and chicanery of politics, but he believed deeply that politics was necessary, that from politics came laws, the only way a democratic society could avoid chaos.

An enormous frieze, cast in bronze, was draped across the front of the House chamber. On the left, it depicted Cuba’s struggle for freedom, and on the right, the benefits of liberty. In the rear of the chamber was a second-floor public gallery framed by a colonnade of eighteen Corinthian columns that rose to a soaring, skylit ceiling. Above the columns, 4another frieze displayed sepia motifs on themes ranging from motherhood to literature, from work to equality, from justice to freedom.

These were the lofty ideals of the republic. But on this afternoon in July 1940, Gustavo knew that the reality below was darker. Since independence from Spain, the republic’s history had been marked by tumult, violence, corruption, and disappointment. The promise of freedom had never been fully realized. Gustavo’s generation was the first to come of age in this fledgling republic. He had run with a crowd of bright young intellectuals and artists, amassed wealth, political stature, and prestige, and then witnessed a terrifying fall into dictatorship.

He tried to right the ship, to establish the pillars of democracy.

They stood—for a while.

Gustavo was born on September 22, 1895, in Camajuaní, a small town in central Cuba. Only months before, the war for independence had begun.

His father, Miguel, an immigrant from Santander in northern Spain, had arrived in a vast stream of migration subsidized by Madrid after 1868 to flood the island and tamp down independence fervor. The immigrants were known as peninsulares, often young and destitute but strong-willed and determined to succeed. Miguel became a prosperous tobacco grower and packer. He was a tall fellow, with a large mustache that curled up at the ends. His wife, María Sánchez de Granada, was a strict disciplinarian known as “Mamabella.” Gustavo was the second of their five sons and a daughter.

When Gustavo was born, one of the first family friends to come by with congratulations was Gerardo Machado, twenty-four years old. Machado and his father had once been cattle raiders; now they were in the tobacco business, like Miguel. The families were very close. Gerardo had been injured working in a butcher shop in Camajuaní and had only three fingers on his left hand.

Machado cradled the infant Gustavo in his arms. Then he went off to fight with the rebel army.

• • •

5The first Cuban war for independence from Spain, the Ten Years’ War, 1868 to 1878, had ended with a treaty that was supposed to be followed by reforms and autonomy, but promises went unfulfilled and Cubans remained under the Spanish boot. The Spanish captain general in Cuba had absolute authority: he could ban public meetings; elections were corrupt; critics could be exiled. The peninsulares prevailed at the polls and dominated politics. They held majorities in the colonial government, provincial and city governments, the military, and the clergy, as well as judges, magistrates, prosecutors, solicitors, court clerks, and scribes.

To throw off Spanish rule, a ragtag rebel army began fighting anew in early 1895. It was a conflict of steel ripping flesh, charred fields, and ghastly death camps. General Maxímo Gómez, the commander of the rebel army, waged guerrilla warfare against Spanish troops that outnumbered him five to one. Determined to deny Spain the rich bounty of Cuba’s harvests, Gómez destroyed the economy of the island he was defending, wrecking Cuba’s sugar plantations and mills. He targeted the big planters, manufacturers, mining operations, and lines of communication. Bridges and rail lines were dynamited. Tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs, with no choice but to join the rebel forces or become refugees. One night on the battlefield, Gómez wrote by candlelight that “Cuba’s wealth is the cause of her bondage” to Spain, thus the rebels “are determined that everything must be destroyed.” His rebels had no uniforms, small rations, and old rifles, shotguns, and pistols. By legend, their most fearsome weapon was the machete, a large, heavy-backed knife with a sharp edge about two feet long, a curving blade and thick wooden handle, ideal for sugarcane harvesting. While the machete was terrifying, it was more symbol than combat weapon. Far more lethal were the well-aimed sharpshooters in the rebel ranks. While the first war had been fought in the east, this time the rebels, led by Antonio Maceo, a veteran of the Ten Years’ War, spread what one historian called “flame and misery, pillage and plunder” to the west and across the whole island. Slavery had ended in 1886, but Cuban society continued to be deeply divided along racial lines. Black and mixed-race Cubans joined 6the rebel army en masse, many harboring dreams of a better place for themselves in a free Cuba.

Spain fought back with its own scorched earth tactics. General Valeriano Weyler, a veteran of the Ten Years’ War, forced a million Cubans into crude garrison towns and guarded encampments surrounded by barbed wire. Death was the penalty for escape. Both soldiers and civilians succumbed to waves of yellow fever. Starvation set in. More than 100,000 people died—perhaps up to 170,000—in the policy of “reconcentration.” Even after the policy ended in 1897, hundreds died every day in the major towns and cities, many interred in mass graves, or their bodies left stacked by the roadside for wild dogs and birds. “The country was wrapped in the stillness of death and the silence of desolation,” wrote a former congressman, William J. Calhoun, on visiting Cuba at the request of President McKinley in 1897.

The USS Maine was sent to Havana to signal concern for the substantial US economic interests in Cuba. On several occasions, the United States attempted to buy the island from Spain, and groups in both Cuba and the United States had sought annexation. When the ship was destroyed by a blast in the Harbor of Havana on February 15, 1898, killing 266, a war cry erupted in the United States, fueled by sensationalist journalism that blamed Spain, although no proof was ever found. Twelve weeks after the United States declared war, following the Battles of San Juan and Kettle Hills and the destruction of the Spanish fleet in the Port of Santiago de Cuba, a weary Spain surrendered Cuba, its last colony in the New World. The formal handover to the United States came on January 1, 1899.

The island’s fields were blackened, pastures barren, fruit trees bare. Two generations of Cubans had embraced the fight for independence; many had devoted the better part of their adult lives to the cause and were now impoverished. The island was deeply divided; more than 60,000 Cubans had served on the Spanish side in various auxiliary capacities during the war, far exceeding the 40,000 rebel troops. Cuba’s population was 1.5 million at war’s end, a devastating loss of some 300,000. The island was a smoking ruin and not yet entirely free.7

The United States established a military occupation of Cuba from January 1899 to May 1902, building hundreds of schools and improving public health. Cuban doctor Carlos Finlay’s discovery that mosquitoes transmitted yellow fever was verified, leading to improved sanitary conditions. At the same time, the US occupiers arrived with a haughty sense of superiority. Leonard Wood, the second military governor, ordered Cuban schools reorganized, “adapting them as far as practicable to the public school system of the U.S.” Cuba’s new draft constitution was patterned on the United States’ separation of powers. Wood, a general with a medical degree from Harvard University, had commanded the Rough Riders, the volunteer cavalry unit that fought to expel the Spanish, with Theodore Roosevelt as his second-in-command. He believed that after a brief period Cubans would want to be annexed by the United States. He looked down upon them as needing “new life, new principles and new methods.” He wrote President McKinley in April 1900, “The people here, Mr. President, know that they are not ready for self-government.” He wrote to Secretary of War Elihu Root, “These men are all rascals and political adventurers whose object is to loot the Island.” This attitude was held widely in the United States, too. In newspaper cartoons, Cubans were portrayed with racist, humiliating tropes, as infants; rowdy, undisciplined youths; and out-of-control gun-toting delinquents, all requiring constant guidance and tutelage from North America. The rebel army, which fought for three years before the United States intervened, was not even acknowledged in the peace treaty with Spain and was excluded from the signing ceremony. When one of their most senior and revered commanders, Major General Calixto García, passed away, the United States organized a military parade on February 11, 1899, to carry him to Havana’s Colón Cemetery. But due to a misunderstanding, the rebel fighters were told to march in the rear. Indignant, they abandoned the procession. The rebel army was disbanded later that year.

The war marked the first US territorial expansion outside the North American continent: the Philippines, where rebels fought for independence for several years; Guam, which fell under US control; Puerto Rico, which became a US territory; and Hawaii, which was annexed by the 8United States. What to do with Cuba? In 1901, in exchange for ending the military occupation, Cuba’s first constitutional convention was forced to accept a provision that gave the United States “the right to intervene” in the island’s affairs for “the maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property and individual liberty.” This was the Platt Amendment, named after Senator Orville H. Platt, Republican of Connecticut and chairman of the Senate Committee on Relations with Cuba, who insisted that the United States had a duty to preserve stability on the island. The amendment, largely based on a memorandum written by Root, was approved as a rider to an appropriations bill and signed by McKinley on March 2, 1901. It was a fateful decision. Cuba was hamstrung from signing treaties with other countries, and severely limited in taking on debt. Despite serious misgivings, the Cubans accepted the terms in June; it was made clear to them that they had no choice. The Platt Amendment became an appendix to Cuba’s 1901 constitution. The island became a quasi-protectorate of the United States, putting it in a legal and political chokehold that would have consequences for decades.

Tobacco rebounded quickly after the war, and Miguel Gutiérrez survived the devastation. In 1900, he moved his family to Havana, which had fared better in the war than most places in Cuba. A photograph shows Miguel seated outdoors in a wicker chair and holding a rolled document. Mamabella is nearby, surrounded by five of their children, including a skinny Gustavo, his arm around a younger brother.

Gustavo was sent to Cuba’s best schools, including the prestigious Jesuit preparatory academy Colegio de Belén. The Jesuits placed a heavy emphasis on classic literature, Latin, and Greek. He had been bookish as a young boy and was smart and a quick learner.

When Gustavo was twelve years old, the United States returned to rule Cuba in a second intervention. Political forces behind the island’s first president, Tomás Estrada Palma, had committed fraud in his reelection campaign, prompting his opponent, the popular war general José Miguel Gómez, to organize an armed insurrection. Estrada Palma resigned, leaving Cuba rudderless. President Theodore Roosevelt sent in 9the marines and installed a civilian administrator, Charles Magoon, from 1906 to 1909, another potent reminder of the Platt Amendment. In 1912, the Partido Independiente de Color, a political party of Black Cubans who were seeking to take part in upcoming elections, staged an armed protest out of fear of being excluded. The government responded with brutal force, killing hundreds. The United States landed troops again, on a smaller scale; and once more in 1917 to protect US sugar plantations at a time of unrest.

Gustavo’s parents sent him to the United States for a year, attending St. Ann’s Academy, a Marist Brothers school in Manhattan, to sharpen his English. On his return to Cuba, he prepared for university at the Instituto de La Habana, the equivalent of a high school. Lanky but muscular, he excelled in baseball, traveling to Cincinnati to play in US youth leagues. Gustavo was an exacting catcher. A friend later wrote, “When I close my eyes, I can see a thin, athletic Gustavo standing tall, always minding his position, paying close attention to everything, fully involved in the contest, impeccably framing the pitch, remaining completely calm, not squabbling with his rivals; in short, foreshadowing what would later be his typical demeanor throughout his life: somewhat reserved, somewhat cold.”

Gustavo entered the University of Havana, Cuba’s only center of higher learning. Fewer than one adolescent in twenty at the time went beyond six years of public schooling. At the university, the schools of law and medicine were the largest, overshadowing almost all others, because they were valuable stepping-stones to professions. The university, neglected at the end of Spanish rule, had been reinaugurated after the war, and moved to a hilltop location in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood. It was still plagued with problems, however, including no-show professors on the payroll. Gustavo graduated in 1916 with a doctorado degree in civil law, and a year later with a second doctorado in public law, both with honors.

From his late teens, Gustavo had single-mindedly courted María Vianello, the vivacious daughter of a tobacco planter. Like Gustavo, María received the best schooling of the day, studying French at the prestigious 10El Colegio Francés de Leónie Olivier in Havana, traveling to Paris, and later studying piano, mandolin, and painting. They married in 1918, living for a while with his parents.

The dean of Havana’s legal establishment, Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante, spotted Gustavo as a smart young law student. With a distinctive white mustache and neatly trimmed beard, Bustamante was Cuba’s most respected legal mind. He gave Gustavo an internship in his law firm when he was twenty years old and still a student, then a lawyer’s job, for a year, upon graduation. Bustamante held a chair in international law at the university. When he was sent as Cuba’s diplomatic representative to the Paris peace talks in 1919, he appointed Gustavo to teach his classes. When six new assistant professorships were created—the school desperately needed qualified faculty—one went to Gustavo to teach international public law. He soon became secretary-treasurer of the Cuban Society for International Law, of which Bustamante was president. Bustamante’s law firm represented foreign companies and banks in their expansive interests in Cuba. Gustavo was exposed to the nexus of money and influence, and the sizable share of the economy that was dominated from abroad.

Gustavo’s circle of friends were lively young intellectuals and artists who gathered for hours of intense criticism, debate, and camaraderie. On Saturdays, they often assembled at the offices of Social, Cuba’s premier cultural monthly magazine, founded by Conrado Massaguer, a caricaturist, illustrator, and satirist whose elegant drawings graced the cover of each issue. After meeting at Social, Gutiérrez and his friends moved to the cafés. A favorite was the popular café at the Teatro Martí, a complex with patios and gardens, pomegranates, and orange and banana trees. Here Gutiérrez was joined by the leading lights of a restless new generation: the literary editor of Social, Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring, a graduate of Belén and the university’s law school; the poet Rubén Martínez Villena; the author and thinker Jorge Mañach, a Harvard graduate; and writers Juan Marinello and Enrique Serpa. The poet and journalist Andrés Nuñez Olano recalled the café was where “we would tirelessly discuss 11with each other; we would bring up something we had recently written or read, throwing it out there as if it were a challenge; we would lay into people and their reputations; we would fiercely critique each other; we would drop names, waving them high like banners or trampling upon them like rags; we would outwardly express, in the same tones, what enraged us, what excited us, what disappointed us … in short, we magnificently lived out our remarkable youth.”

All of them were in their twenties and deeply discouraged by Cuba’s direction. They were passionate about the need for a wholesale “rejuvenation,” or “regeneration.” The great promise of independence—dramatic change, a free and sovereign Cuba—had faded. They blamed the generation of the independence war, especially Cuba’s second, third, and fourth presidents. As historian Lillian Guerra put it, the war generation had “presided over the stillbirth rather than the birth of a republic.”

After the US intervention, the second elected president was José Miguel Gómez, an attractive figure with cattleman gusto who rose to major general in the rebel army. He took the presidency in 1909 as a poor man and left in 1913 as a millionaire with a new marble palace in Havana. When visitors came seeking favors, he was said to genially offer them cigars, in a box, into which they were expected to put the bribes. The third president, Mario Menocal, who had been a major general in the war, looked the other way at substantial stealing by his friends and relatives. The fourth and current president, Alfredo Zayas, who took office in 1921, was a perpetual political striver, lawyer, and poet who had formed his own party. Zayas was not a battlefield war hero but had been outspoken for the rebellion and was captured by the Spanish and deported. He was a slight man, timid, with bad teeth and a yellowish complexion, but brilliantly clever, and known as someone who never hesitated to take the smallest graft. On the eve of his inauguration, a columnist in Social compared Zayas to an eel: slippery.

It was painfully evident to Gustavo and his friends that, as historian Luis A. Pérez Jr. wrote, “Almost everything turned out different than the way it was supposed to be.” Much of Cuba’s wealth and opportunity were beyond the reach of the Cubans themselves. Foreigners prevailed 12over production and property; sugar, banks, railways, public utilities, and other enterprises were dominated by interests from the United States and elsewhere. Also, fresh waves of Spanish immigrants surged to Cuba after the independence war. Some seven hundred thousand arrived between 1902 and 1919, mostly young, ambitious, poor, and in pursuit of riches. They controlled retail commerce and made up more than half the merchants on the island. They were strongly represented in the professions, education, and the press, and the Catholic Church remained substantially a Spanish Church. This meant that Cubans were squeezed into one area where they could succeed and survive, government and politics, where the levers of power dispensed patronage and graft. The public treasury became the largest employer of the middle class. “Corruption developed into a pervasive presence in Cuban public life,” wrote Pérez. “Graft, bribery, and embezzlement served as the medium of political exchange.” A job in Cuba’s bureaucracy was called un destino, “a destiny,” or a salvation, and election campaigns celebrated as the “second harvest,” after sugar. Public office-holders rewarded their families and supporters with money, land, licenses, contracts, franchises, and concessions. By one estimate in 1921, Cuba’s government spent $15 million a year on botellas, or no-show jobs and sinecures.

At the café where Gustavo met his friends, there was much soul-searching. How had the ideals of independence gone off the rails? Cuba seemed unable to govern itself. Not only in politics; the social sphere was also a mess. “Cuban society is disintegrating,” warned the respected anthropologist Fernando Ortiz. More than half the population could not read or write and, alarmingly, illiteracy was growing. Although Cuba’s population had doubled since the independence war, school enrollment fell. In 1900, seventy-five students per thousand residents were in classrooms; now it was fifty per thousand. Even more alarming, the school dropout rate was abysmally high. “So,” said Ortiz, “our poor little Cubans leave school, when they have attended it, at the age of thirteen or fourteen, with an education of age eight or nine.” Cuba, he said, was becoming a “twentieth-century republic with mid-nineteenth-century mentality and habits.”

Gustavo and his friends witnessed a culture of impunity. Legislators 13enjoyed constitutional immunity from criminal prosecution; at the same time, amnesty bills were routinely passed, setting aside past convictions, and pardons were granted by the thousands. Fully a fifth of all candidates for political office in the 1922 elections had criminal records, Ortiz lamented.

Black Cubans and those of mixed-race heritage, a third of Cuba’s population, had been promised social justice and political equality after independence but received neither. After the war, nine-tenths of the sugar and tobacco production was white-controlled, as was most of the livestock, while Black Cubans mostly held small farms. In the professions, Black presence was very small. In 1907 there were only four Black lawyers and nine doctors on the island. But Cubans of color were predominant as laundresses, dressmakers, builders, shoemakers, woodcutters, tailors, musicians, domestic servants, bakers, and barbers. By 1919, among Black males twenty-one years old and over, the illiteracy rate was more than 48 percent, compared to 37 percent for whites. A total of 10,123 Cuban white men more than twenty-one years old had received professional or academic degrees, compared to 429 Black Cubans.

In January 1919, Gustavo took the café debates to a wider audience in a speech he delivered to the Cuban Society for International Law. He was just twenty-three years old, but a protégé of the respected Bustamante. His words reflected the worries of many. He decried Cuba’s “great national evils” but said they were partially rooted in the people themselves. “The incompetence of the governors,” he declared, “befits the indifference of the governed, the passivity of the Congress, the foolishness of the voters, the lack of direction of our international politics, and the disorder of our inner life.” He then insisted that Cuba must begin a wholesale change in its political culture. “Start over,” he said. “This is what we have to do.” It was not enough to create laws and institutions, he insisted. Citizens had to be taught about honor and the meaning of good government. Someday, he predicted, a generation would come of age with “public servants known for their integrity and admired for their skill,” with judges “who always try to get to the bottom of the issues” and democratic presidents “who live by the people and for the people.”14

“Liberty can be gained,” he concluded, “but never given up.” It was an appeal to Cubans not to retreat. But the situation was about to go from bad to worse.

They called it the “dance of the millions.”

After World War I, Germany’s sugar beet crop was decimated. The United States ended war price controls. As a result, the price for Cuban sugar skyrocketed. The 1919 to 1920 crop brought in an astounding $1 billion, more than all the harvests from 1900 to 1914.

Bank deposits soared, luxury goods flooded the stores, and property values zoomed. Cubans and foreigners engaged in speculation, price fixing, bank manipulation, and credit pyramids. A luxurious residential area, Miramar, spread out to the west of Havana, with elegant avenues bordered by flowering trees and shrubs. In the evenings, limousines cruised up and down the seaside Malecón Boulevard, the women in dresses designed in Paris, with billowy scarves and sparkling jewels. New casinos opened, famous opera stars performed, world-champion boxers fought, horses raced for staggering purses. Money cascaded down to the cane workers and farmers known as colonos, who could buy their first necktie or patent leather shoes or put money down on a phonograph. All of it was built on a dizzying expansion of credit, borrowed on sugar.

Then it all crashed. As competing supplies of sugar from elsewhere began to enter the world market, prices collapsed. In Cuba, unemployment, strikes, and shortages broke out. The domestic banking system nearly failed. In 1920, foreign banks held only 20 percent of the total deposits in Cuba, but by 1923, more than 76 percent were in foreign banks. One result of the crash was that even more sugar mills were taken over by US banks when they defaulted on loans or went bankrupt; National City Bank took over nearly sixty mills after the owners went bust.

Despite the crash, sugar remained the most powerful engine of Cuba’s economy. In the first twenty-five years after independence, when Cuba became the single largest producer in the world, national income quadrupled. Sugar demanded land, labor, and capital. For land, vast latifundios were created, estates with, as Ortiz, the anthropologist, put it, 15“territories so large that in other countries they would be provinces.” For labor, Cuba began importing tens of thousands of workers from Haiti and Jamaica, and many stayed on, to find jobs in the cities.

For capital, the main source was the United States. Although the statistics are imprecise because of hidden ownership, by 1919 mills owned by US interests produced 51.4 percent of Cuba’s sugar. The Cubans had 22.8 percent, and Spanish interests were 17.3 percent. There were prominent exceptions, such as Havana sugar king Julio Lobo. The US sugar mills, however, were far more efficient than others, and US interests also controlled the railroads, the phone system, the docks, and the banks.

In the aftermath of the crash, Gustavo and his friends again asked: What went wrong?

Their discontent led them to rediscover José Martí.

In the first years of the republic, Martí was not widely known on the island, regarded as a faded revolutionary martyr. But Gustavo and his generation found more and more about him to admire.

Martí was born in Havana in January 1853. His father, Mariano, was a Spanish sergeant who later became a police inspector. His mother, Leonor, came from a Spanish military family in the Canary Islands who immigrated to Cuba. Although Mariano would later encounter economic troubles, when José was born they were a relatively affluent military couple, living a few blocks from the sea on the outskirts of Old Havana. José was a precocious student, tutored by a famous poet and educator, Rafael Mendive. Imbued with his teacher’s rebellious spirit, Martí formed a young “revolutionary” club in school, and when he was sixteen years old he wrote a letter urging a former classmate, a Spanish military cadet, to desert. When the letter was discovered, Martí was charged with conspiracy, and after a trial, sentenced to six years of forced labor, including at a limestone quarry. The quarry was a hellish scene for prisoner 113: massive walls of limerock; the sun’s fierce heat; prisoners excavating with picks and sledgehammers; quicklime burning their feet; and a fine, white powdery dust choking their lungs. Martí’s ankles were rubbed raw by the prison chains, his eyes burned by the blinding whiteness. In the quarry he 16saw the horrors of political imprisonment in Cuba, and it left him with a deep loathing of Spanish colonial rule. After six months, he was released, thanks to lobbying by his parents and the intervention of a friend of his father. He was exiled to Spain at age seventeen, where he unenthusiastically studied law. He was more attracted to philosophy and literature. Four years later, he sailed to Mexico to join his parents, who had settled there, and was drawn into politics. “Except for literature, nothing interested him so much as politics,” wrote biographer Jorge Mañach. “The art of making a people and ruling them impressed him as something magical….” After protesting a regime in Mexico installed by a military coup, Martí taught for a year in Guatemala, and in 1878 returned to Cuba, where he became active in the underground resistance, and was banished again to Spain. Soon he arrived penniless in New York City, and, still restless, traveled to Venezuela, where a dictatorship again forced him to depart. Back in New York in 1881, he began an extraordinary fourteen years of journalism—and activism for an independent Cuba.

He worked from a tiny room in a New York boardinghouse. “A good part of the day and night he spent at the table in a sea of newspapers and magazines, filling sheet after sheet of copy paper with a handwriting made almost illegible by intellectual drive,” wrote Mañach. He earned money as an accountant by day, and by night wrote poems of lyric intensity for a new book, Versos Libres. In 1882, he began writing for the great Buenos Aires daily La Nación, and his reputation for reportage and commentary spread across Latin America. Martí was an observant witness to the rise of the American experiment. In his dispatches, he denounced the materialism, prejudice, expansionist arrogance, and political corruption he found in the United States, but he embraced the love of liberty, tolerance, egalitarianism, and the practice of democracy there. In New York he worked as an editor, translator, secondary-school teacher, university professor, diplomat, and playwright while tirelessly squeezing in time to advocate independence for Cuba. A political thinker and revolutionary, a prodigious writer, teacher, poet, and tireless organizer, Martí laid the foundations for Cuba’s war of independence.

Martí possessed an almost mystical faith in democracy. “There isn’t 17a throne that can compare to the mind of a free person,” he wrote. “As the bones to the human body, the axle to the wheel, the wing to the bird, and the air to the wing, so is liberty the essence of life. Whatever is done without it is imperfect.” Martí was convinced that the next drive for Cuban independence should be a people’s uprising, a wave of civilians. The war was just the starting point, he thought; it had to lead to the republic of tomorrow, free of dictatorship. He was alarmed that Máximo Gómez—whom he needed to lead the battle—remained a stubborn authoritarian. In 1884, Martí met Gómez and Antonio Maceo in New York. The two great military chieftains looked down on Martí; Gómez thought Martí was a better poet than revolutionary, and Maceo thought Martí was unlikable and unreliable, a schemer rather than a soldier. At one point, Gómez brusquely told Martí to “limit yourself to obeying orders.” In protest, Martí wrote a long letter to Gómez in which he warned against swapping “the present political despotism in Cuba for a personal despotism, a thousand times worse.” Martí added, “One does not establish a people, General, the way one commands a military camp.”