Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

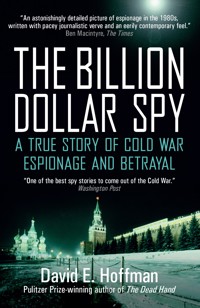

WATERSTONES NON-FICTION BOOK OF THE MONTH AUGUST 2018 AND A SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLER 'An astonishingly detailed picture of espionage in the 1980s, written with pacey journalistic verve and an eerily contemporary feel.' Ben Macintyre, The Times 'A gripping story of courage, professionalism, and betrayal in the secret world.' Rodric Braithwaite, British Ambassador in Moscow, 1988-1992 'One of the best spy stories to come out of the Cold War and all the more riveting for being true.' Washington Post January, 1977. While the chief of the CIA's Moscow station fills his gas tank, a stranger drops a note into the car. In the years that followed, that stranger, Adolf Tolkachev, became one of the West's most valuable spies. At enormous risk Tolkachev and his handlers conducted clandestine meetings across Moscow, using spy cameras, props, and private codes to elude the KGB in its own backyard - until a shocking betrayal put them all at risk. Drawing on previously classified CIA documents and interviews with first-hand participants, The Billion Dollar Spy is a brilliant feat of reporting and a riveting true story from the final years of the Cold War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 613

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for David E. Hoffman’s

THE BILLION DOLLAR SPY

‘The Billion Dollar Spy is one of the best spy stories to come out of the Cold War and all the more riveting … for being true. It hits the sweet spot between page-turning thriller and solidly researched history … and then becomes something more, a shrewd character study of spies and the spies who run them, the mixed motives, the risks … This is a terrific book.’

Washington Post

‘A fabulous read that also provides chilling insights into the Cold War spy game between Washington and Moscow that has erupted anew under Vladimir Putin … It is also an evocative portrait of everyday life in the crumbling Soviet Union and a meticulously researched guide to CIA sources and methods. I devoured every word, including the footnotes.’

Michael Dobbs, author of One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War

‘The Billion Dollar Spy reads like the very best spy fiction yet is meticulously drawn from real life. It is a gripping story of courage, professionalism, and betrayal in the secret world.’

Rodric Braithwaite,British Ambassador in Moscow, 1988–92

‘A true-life tale so gripping at times it reads like spy fiction.’

Los Angeles Times

‘Engrossing … Mr Hoffman’s book particularly shines in cinematic accounts of … anxious encounters.’

New York Times

‘A rare look at the dangerous, intricately choreographed tradecraft behind old-school intelligence gathering … What [Hoffman]’s accomplished here isn’t just a remarkable example of journalistic talent but also an ability to weave an absolutely gripping nonfiction narrative.’

Dallas Morning News

‘Hoffman excels at conveying both the tradecraft and the human vulnerabilities involved in spying.’

The New Yorker

‘Gripping and nerve-wracking … Human tension hangs over every page of The Billion Dollar Spy like the smell of leaded gasoline … [Hoffman] knows the intelligence world well and has expertly used recently declassified documents to tell this unsettling and suspenseful story. … The Billion Dollar Spy reads like the most taut and suspenseful parts of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy or Smiley’s People. It’s worth the clenched jaw and upset stomach it creates.’

USA Today

‘Suspenseful … Hoffman is a scrupulous, meticulous writer whose pages of footnotes and references attest to how carefully he sticks to his sources … His book’s value is in its true-life adventure story and the window it offers into a once-closed world.’

Columbus Dispatch

‘Hoffman viscerally evokes the secret, ruthless Cold War battle between the American Central Intelligence Agency and the Soviet KGB in his true-life espionage thriller … An exciting, revealing tale with a courageous, sympathetic protagonist.’

Tampa Bay Times

‘The fine first sentence of The Billion Dollar Spy could almost have been written with an icicle. A work of painstaking historical research that’s paced like a thriller.’

Departures

‘Hoffman [proves] that nonfiction can read like a John le Carré thriller … This real-life tale of espionage will hook readers from the get-go.’

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

‘Fascinating … Hoffman’s revealing of [Adolf Tolkachev] as a person and a spy is brilliantly done, making this mes-merizing true story scary and thrilling.’

Booklist (starred review)

‘Hoffman ably navigates the many strands of this complex espionage story. An intricate, mesmerizing portrayal of the KGB-CIA spy culture … A thoroughly researched excavation of an astoundingly important (and sadly sacrificed) spy for the CIA.’

Kirkus Reviews

‘This riveting drama … packs valuable insights into the final decade of the cloak-and-dagger rivalry between the United States and the former Soviet Union … A must-read for historians and buffs of that era, as well as aficionados of espionage.’

Christian Science Monitor

‘One of the best real-life spy stories ever told. This is a breakthrough book in intelligence writing, drawing on CIA operational cables—the holy grail of the spy world—to narrate each astonishing move. Hoffman reveals CIA tradecraft tricks that are more delicious than anything in a spy novel, and his command of the Soviet landscape is masterful. Full of twists so amazing you couldn’t make them up, this is spy fact that really is better than fiction.’

David Ignatius, author of The Director

‘A scrupulously researched work of history that is also a gripping thriller, The Billion Dollar Spy by David E. Hoffman is an unforgettable journey into Cold War espionage. This spellbinding story pulses with the dramatic tension of running an agent in Soviet-era Moscow—where the KGB is ubiquitous and CIA officers and Russian assets are prey. I was enthralled.’

Peter Finn, co-author of The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book

THE BILLION DOLLAR SPY

To Carole

Everything we do is dangerous.

—Adolf Tolkachev, to his CIA case officerOctober 11, 1984

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Two retired CIA officers, each with decades of experience in the clandestine service, generously contributed time and effort to this project. Burton Gerber, who served as both chief of the Moscow station and Soviet division chief, devoted hours to research into the original cables, with the agency’s approval and clearance of the materials before release to me. He provided invaluable guidance and context for the Tolkachev story. Barry Royden, who authored an internal CIA monograph on the operation in the 1990s, was an early enthusiast for the book and a source of great insight. Both helped to navigate the declassification process and demystify the world of espionage.

I wish to express special thanks to Ron, chief of the CE division at the CIA when the project began, who provided critical support for declassification of the operational files. He remains in the clandestine service so cannot be further identified. I also benefited from the recollections of David Forden, Robert Fulton, Sandra Grimes, Gardner “Gus” Hathaway, Thomas Mills, Robert Morris, James Olson, Marti Peterson, William Plunkert, David Rolph, Michael Sellers, Haviland Smith, and Robert Wallace. Catherine Guilsher generously provided recollections of John’s life and times. Karin Hathaway graciously helped with memories of Gus. John Ehrman provided an important link to the agency. My thanks also to several retired intelligence officers who agreed to share their knowledge and recollections without being identified.

In Moscow, I was assisted by Anna Masterova, who skillfully sifted archives, conducted interviews, and translated. I also am grateful to Irina Ostrovskaya of Memorial International for archival records on the repression of the Kuzmin family. Volodya Alexandrov and Sergei Belyakov were, as always, selfless and ready to help at every turn. Masha Lipman has been a peerless source of wisdom and insight about Russia for two decades, and provided perceptive and detailed comments on the draft manuscript.

Maryanne Warrick transcribed interviews and carried out research assignments, and I am grateful for her precision and tireless efforts. Charissa Ford and Julie Tate also contributed research.

At the Washington Post, I was fortunate to be part of a golden age of journalism built by Don Graham and Katharine Graham, and I am grateful to the executive editors Benjamin C. Bradlee and Leonard Downie for giving me the opportunity to contribute to it. I am particularly thankful for years of advice and support from Philip Bennett, a colleague and friend with whom I shared some of the best years in the newsroom and who gave me an important critique of the manuscript. Robert Kaiser has been a model and mentor, and Joby Warrick a valued friend and adviser. Peter Finn and Michael Birnbaum, talented Moscow bureau chiefs, offered their cooperation and help.

I am indebted to H. Keith Melton for sharing images from his collection and to Kathy Krantz Fieramosca for permission to reproduce her painting of Adolf Tolkachev. I wish to thank Jack F. Matlock, Dick Combs, and James Schumaker for recollections of the 1977 fire at the Moscow embassy. For insights about radar and air defenses, I am grateful to David Kenneth Ellis, William Andrews, Robin Lee, and Larry Pitts. I also received valuable advice and help from Robert Berls, Benjamin Weiser, Fritz Er marth, Charles Battaglia, Jerrold Schecter, Robert Monroe, Peter Earnest, George Little, Louis Denes, Matthew Aid, Joshua Pollack, and Jason Saltoun-Ebin. Cathy Cox of the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base fulfilled requests professionally and promptly. I am grateful for access to the collections of the National Security Archive, Washington, D.C.; the National Archives at College Park, Maryland; the U.S. Naval Institute Oral History Program, Annapolis, Maryland; the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Simi Valley, California; and the Russian State Archive of the Economy, Moscow.

Glenn Frankel has been a mentor on writing for years and once again gave me perceptive and valuable comments on the manuscript. I am also grateful to Svetlana Savranskaya for comments on a draft and sharing her knowledge about how to pry Cold War secrets out of the world’s archives.

For the second time in a decade, the wise and patient editing of Kris Puopolo steered me from a hazy vision and a box full of loose documents to a finished narrative, and I am deeply appreciative. My thanks, too, to Bill Thomas for believing this book would be worthy of Doubleday. I thank Daniel Meyer for keeping the project on track. I’m grateful to Esther Newberg for being an extraordinary agent. Her first phone call upon reading the draft manuscript, full of enthusiasm, was a moment to cherish.

My deepest gratitude goes to my wife, Carole, who lovingly guided our own Moscow station, with our sons, Daniel and Benjamin, when I was a correspondent for the Washington Post in the late 1990s. She offered advice and insight at every stage of this project. More important, she endured the disruptions and unpredictable twists and turns that come with a life in journalism but never lost a conviction that discovering the world was a voyage worth taking. For as long as I can recall, a small scrap of paper has been fastened to our refrigerator door with a proverb from Saint Augustine: “The world is a book, and those who do not travel, read only a page.” With her steadfast support and participation, the world is, once again, a book.

CONTENTS

MAP

PROLOGUE

1 OUT OF THE WILDERNESS

2 MOSCOW STATION

3 A MAN CALLED SPHERE

4 “FINALLY I HAVE REACHED YOU”

5 “A DISSIDENT AT HEART”

6 SIX FIGURES

7 SPY CAMERA

8 WINDFALLS AND HAZARDS

9 THE BILLION DOLLAR SPY

10 FLIGHT OF UTOPIA

11 GOING BLACK

12 DEVICES AND DESIRES

13 TORMENTED BY THE PAST

14 “EVERYTHING IS DANGEROUS”

15 NOT CAUGHT ALIVE

16 SEEDS OF BETRAYAL

17 VANQUISH

18 SELLING OUT

19 WITHOUT WARNING

20 ON THE RUN

21 “FOR FREEDOM”

EPILOGUE

A NOTE ON THE INTELLIGENCE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

THE BILLION DOLLAR SPY

PROLOGUE

The spy had vanished.

He was the most successful and valued agent the United States had run inside the Soviet Union in two decades. His documents and drawings had unlocked the secrets of Soviet radar and revealed sensitive plans for research on weapons systems a decade into the future. He had taken frightful risks to smuggle circuit boards and blueprints out of his military laboratory and handed them over to the CIA. His espionage put the United States in position to dominate the skies in aerial combat and confirmed the vulnerability of Soviet air defenses—that American cruise missiles and bombers could fly under the radar.

In the late autumn and early winter of 1982, the CIA lost touch with him. Five scheduled meetings were missed. Months had gone by. In October, an attempt to rendezvous with him failed because of overwhelming KGB surveillance on the street. Even the “deep cover” officers of the CIA’s Moscow station, invisible to the KGB, could not break through. On November 24, a deep cover officer, wearing a light disguise, managed to call the spy’s apartment from a pay phone, but someone else answered. The officer hung up.

On the evening of December 7, the next scheduled meeting, the future of the operation was put in the hands of Bill Plunkert. After a stint as a navy aviator, Plunkert had joined the CIA and trained as a clandestine operations officer. He was in his mid-thirties, six feet two, and had arrived at the Moscow station in the summer for a tour devoted to handling the spy. He pored over the files, studied maps and photographs, read cables, and talked to the case officers. He felt he knew the man, even though he had never met him face-to-face. His mission was to give the slip to the KGB and make contact.

In the days before, using the local phone lines they knew were tapped by the KGB, a few American diplomats had organized a birthday party at an apartment for Tuesday evening. That night, around the dinner hour, four people walked to a car in the U.S. embassy parking lot, under constant watch by uniformed militiamen who stood outside and reported to the KGB. One of the four carried a large birthday cake. When the car left the embassy, a woman in the rear seat behind the driver held the cake on her lap.

Driving the car was the CIA’s chief of station. Plunkert sat next to him in the front seat. Their wives were in back. All four of them had earlier rehearsed what they were about to do, using chairs set up in the Moscow station. Now the real show was about to begin.1

Espionage is the art of illusion. Tonight, Plunkert was the illusionist. Under his street clothes, he wore a second layer of clothes that would be typical for an old Russian man. The birthday cake was fake, with a top that looked like a cake but concealed a device underneath created by the CIA’s technical operations wizards. Plunkert hoped the device would give him a means of escape from KGB surveillance.

The device was called the Jack-in-the-Box, known to all as simply the JIB. Over the years, the CIA had learned that KGB surveillance teams almost always followed a car from behind. They rarely pulled alongside. It was possible for a car carrying a CIA officer to slip around a corner or two, momentarily out of view of the KGB. In that brief interval, the CIA case officer could jump out of the car and disappear. At the same time, the Jack-in-the-Box would spring erect, a pop-up that looked, in outline, like the head and torso of the case officer who had just jumped out.

To create it, the CIA had sent two young engineers from the Office of Technical Service to a windowless sex shop in a seedy area of Washington, D.C., to purchase three inflatable, life-sized dolls. But the dolls were hard to inflate or deflate quickly. They leaked air. The young engineers went back to the shop for more test mannequins, but problems persisted. Then the CIA realized that given the distance from which the KGB followed cars in Moscow, it wasn’t necessary to have a three-dimensional dummy in the front seat, only a two-dimensional cutout. Illusion triumphed, and the Jack-in-the-Box was born.2

The device had not been used before in Moscow, but the CIA had grown desperate as weeks went by, with no contact with the agent. A skilled disguise expert from headquarters was sent to the Moscow station to help with the device and to bring Plunkert some “sterile” clothing that had never been worn before, to avoid any telltale scents that could be traced by KGB dogs or any tracking or listening devices that could be hidden inside.

As the car wound through the Moscow streets, Plunkert took off his American street clothes and put them into a small sack, typical of the kind Russians carried about. Wearing a full face mask and eyeglasses, he was now disguised as an old Russian man. At a distance, the KGB was trailing them. It was 7:00 p.m., well after nightfall.

The car turned a corner, briefly out of view of surveillance. The chief of station slowed the car with the hand brake to avoid illuminating the rear brake lights. Plunkert swung open the passenger door and jumped out. At the same moment, the chief of station’s wife took the birthday cake from her lap and laid it on the front passenger seat where Plunkert had been sitting. Plunkert’s wife reached forward and pulled a lever.

With a crisp whack, the top of the cake flung open, and a head and torso snapped into position. The car accelerated.

Outside, Plunkert took four steps on the sidewalk. On his fifth step, the KGB chase car rounded the corner.

The headlights caught an old Russian man on the sidewalk, then sped off in pursuit. The CIA car still appeared to have four persons inside. With a small handle, the station chief moved the head of the Jack-in-the-Box back and forth, as if it were chattering away.

The JIB had worked.

Plunkert felt a momentary rush of relief, but the next few hours would be the most demanding of all. The agent was extraordinarily valuable, not just for the Moscow station, but for the entire CIA and for the United States. Plunkert shouldered a heavy personal burden. One small error, and the operation would be forever lost. The spy would face execution for treason.

No one at the CIA knew why the spy had disappeared. Was he under suspicion? He was not a professional intelligence officer; he was an engineer. Had he made a careless mistake? Had he been arrested and interrogated and his treason revealed?

Alone, Plunkert walked the Moscow streets, a frigid tableau of slick ice and inky shadows. He thought it was just about perfect for espionage. He talked to himself a lot. A practicing Catholic, Plunkert prayed—little, short prayers. Every time he exhaled under the mask, his eyeglasses fogged up. He stopped after a while, removed the mask, and donned a lighter disguise. He took public trolleys and buses in a roundabout route to the rendezvous point. He watched for KGB surveillance but saw none.

He had to find the spy. He could not fail.

1

OUT OF THE WILDERNESS

In the early years of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, the Central Intelligence Agency harbored an uncomfortable secret about itself. The CIA had never really gained an espionage foothold on the streets of Moscow. The agency didn’t recruit in Moscow, because it was just too dangerous—“immensely dangerous,” recalled one officer—for any Soviet citizen or official they might enlist. The recruitment process itself, from the first moment a possible spy was identified and approached, was filled with risk of discovery by the KGB, and if caught spying, an agent would face certain death. A few agents who volunteered or were recruited by the CIA outside the Soviet Union continued to report securely once they returned home. But for the most part, the CIA did not lure agents into spying in the heart of darkness.

This is the story of an espionage operation that turned the tide. At the center of it is an engineer in a top secret design laboratory, a specialist in airborne radar who worked deep inside the Soviet military establishment. Driven by anger and vengeance, he passed thousands of pages of secret documents to the United States, even though he had never set foot in America and knew little about it. He met with CIA officers twenty-one times over six years on the streets of Moscow, a city swarming with KGB surveillance, and was never detected. The engineer was one of the CIA’s most productive agents of the Cold War, providing the United States with intelligence no other spy had ever obtained.

The operation was a coming-of-age for the CIA, a moment when it accomplished what was long thought unattainable: personally meeting with a spy right under the nose of the KGB.

Then the operation was destroyed, not by the KGB, but by betrayal from within.

To understand the significance of the operation, one must look back at the CIA’s long, difficult struggle to penetrate the Soviet Union.

The CIA was born out of the disaster at Pearl Harbor. Despite warning signals, Japan achieved complete and overwhelming surprise in the December 7, 1941, attack that took the lives of more than twenty-four hundred Americans, sunk or damaged twenty-one ships in the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and thrust the United States into war. Intelligence was splintered among different agencies, and no one pulled all the pieces together; a congressional investigation concluded the fragmented process “was seriously at fault.” The creation of the CIA in 1947 reflected more than anything else the determination of Congress and President Truman that Pearl Harbor should never happen again. Truman wanted the CIA to provide high-quality, objective analysis.1 It was to be the first centralized, civilian intelligence agency in American history.2

But the early plans for the CIA soon changed, largely because of the growing Soviet threat, including the blockade of Berlin, Stalin’s tightening grip on Eastern Europe, and Soviet acquisition of the atomic bomb. The CIA rapidly expanded far beyond just intelligence analysis into espionage and covert action. Pursuing a policy of containment, first outlined in George Kennan’s long telegram of 1946 from Moscow and later significantly expanded, the United States attempted to counter Soviet efforts to penetrate and subvert governments all over the world. The Cold War began as a rivalry over war-ravaged Europe but spread far and wide, a contest of ideology, politics, culture, economics, geography, and military might. The CIA was on the front lines. The battle against communism never escalated into direct combat between the superpowers; it was fought in the shadows between war and peace. It played out in what Secretary of State Dean Rusk once called the “back alleys of the world.”3

There was one back alley that was too dangerous to tread—the Soviet Union itself. Stalin was convinced the World War II victory over the Nazis demonstrated the unshakability of the Soviet state. After the war, he resolutely and consciously deepened the brutal, closed system he had perfected in the 1930s, creating perpetual tension in society, constant struggle against “enemies of the people,” “spies,” “doubters,” “cosmopolitans,” and “degenerates.” It was prohibited to receive a book from abroad or listen to a foreign radio broadcast. Travel overseas was nearly impossible for most people, and unauthorized contacts with foreigners were severely punished. Phones were tapped, mail opened, and informers encouraged. The secret police were in every factory and office. It was dangerous for anyone to speak frankly, even in intimate circles.4

This was a forbidding environment for spying. In the early years of the Cold War, the CIA did not set up a station in Moscow and had no case officers on the streets in the capital of the world’s largest and most secretive party-state. It could not identify and recruit Soviet agents, as it did elsewhere. The Soviet secret police, which after 1954 was named the KGB, or Komitet Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti, was seasoned, proficient, omnipotent, and ruthless. By the 1950s, the KGB had been hardened by three decades of experience in carrying out the Stalin purges, in eliminating threats to Soviet rule during and after the war, and in stealing America’s atom bomb secrets. It was not even possible for a foreigner to strike up a conversation in Moscow without arousing suspicion.

The CIA was still getting its feet wet, a young organization, optimistic, naive, and determined to get things done—a reflection of America’s character.5 In 1954, the pioneering aviator General James Doolittle warned that the United States needed to be more hard-nosed and cold-blooded. “We must develop effective espionage and counter-espionage services and must learn to subvert, sabotage and destroy our enemies by more clever, more sophisticated and more effective methods than those used against us,” he said in a top secret report to President Eisenhower.6

The CIA faced intense and constant pressure for intelligence on the Soviet Union and its satellites. In Washington, policy makers were on edge over possible war in Europe—and anxious for early warning. Much information was available from open sources, but that wasn’t the same as genuine, penetrating intelligence. “The pressure for results ranged from repeated instructions to do ‘something’ to exasperated demands to try ‘anything,’ ” recalled Richard Helms, who was responsible for clandestine operations in the 1950s.7

Outside the Soviet Union, the CIA diligently collected intelligence from refugees, defectors, and émigrés. Soviet diplomats, soldiers, and intelligence officers were approached around the world. From refugee camps in Europe, the CIA’s covert action unit recruited a secret army. Some five thousand volunteers were trained as a “post-nuclear guerilla force” to invade the Soviet Union after an atomic attack. Separately, the United States dropped lone parachutists into the Soviet bloc to spy or link up with resistance groups. Most of them were caught and killed. The chief of the covert action unit, Frank G. Wisner, dreamed of penetrating the Eastern bloc and breaking it to pieces. Wisner hoped that through psychological warfare and underground aid—arms caches, radios, propaganda—the peoples of Eastern Europe might be persuaded to throw off their communist oppressors. But almost all of these attempts to get behind enemy lines with covert action were a flop. The intelligence produced was scanty, and the Soviet Union was unshaken.8

The CIA’s sources were still on the outside looking in. “The only way to fulfill our mission was to develop inside sources—spies who could sit beside the policymakers, listen to their debates, and read their mail,” Helms recalled. But the possibility of recruiting and running agents in Moscow who could warn of decisions made by the Soviet leadership “was as improbable as placing resident spies on the planet Mars,” Helms said.9 A comprehensive assessment of the CIA’s intelligence on the Soviet bloc, completed in 1953, was grim. “We have no reliable inside intelligence on thinking in the Kremlin,” it acknowledged. About the military, it added, “Reliable intelligence of the enemy’s long-range plans and intentions is practically non-existent.” The assessment cautioned, “In the event of a surprise attack, we could not hope to obtain any detailed information of the Soviet military intentions.”10 In the early years of the agency, the CIA found it “impossibly difficult to penetrate Stalin’s paranoid police state with agents.”11

“In those days,” said Helms, “our information about the Soviet Union was very sparse indeed.”12

For all the difficulties, the CIA scored two breakthroughs in the 1950s and early 1960s. Pyotr Popov and Oleg Penkovsky, both officers of Soviet military intelligence, began to spy for the United States. They were volunteers, not recruited, who came forward separately, spilling secrets to the CIA largely outside Moscow, each demonstrating the immense advantages of a clandestine agent.

On New Year’s Day 1953 in Vienna, a short and stocky Russian handed an envelope to a U.S. diplomat who was getting into his car in the international zone. At the time, Vienna was under occupation of the American, British, French, and Soviet forces, a city tense with suspicion. The envelope carried a letter, dated December 28, 1952, written in Russian, which said, “I am a Soviet officer. I wish to meet with an American officer with the object of offering certain services.” The letter specified a place and time to meet. Such offers were common in Vienna in those years; a horde of tricksters tried to make money from fabricated intelligence reports. The CIA had trouble sifting them all, but this time the letter seemed real. On the following Saturday evening, the Russian was waiting where he promised to be—standing in the shadows of a doorway, alone, in a hat and bulky overcoat. He was Pyotr Popov, a twenty-nine-year-old major in Soviet military intelligence, the Glavnoye Razvedyvatelnoye Upravleniye, or GRU, a smaller cousin of the KGB. Popov became the CIA’s first and, at the time, most valuable clandestine military source on the inner workings of the Soviet army and security services. He met sixty-six times with the CIA in Vienna between January 1953 and August 1955. His CIA case officer, George Kisevalter, was a rumpled bear of a man, born in Russia to a prominent family in St. Petersburg, who had immigrated to the United States as a young boy. Over time, Popov revealed to Kisevalter that he was the son of peasants, grew up on the dirt floor of a hut, and had not owned a proper pair of leather shoes until he was thirteen years old. He seethed with hatred at what Stalin had done to destroy the Russian peasantry through forced collectivization and famine. His spying was driven by a desire to avenge the injustice inflicted on his parents and his small village near the Volga River. In the CIA safe house in Vienna, Kisevalter kept some magazines spread out, such as Life and Look, but Popov was fascinated by only one, American Farm Journal.13

The CIA helped Popov forge a key that allowed him to open classified drawers at the GRU rezidentura, or station, in Vienna. Popov fingered the identity of all the Soviet intelligence officers in Vienna, delivered information on a broad array of Warsaw Pact units, and handed Kisevalter gems such as a 1954 Soviet military field service manual for the use of atomic weapons.14 When Popov was reassigned to Moscow in 1955, CIA headquarters sent an officer to the city, undercover, to scout for dead drops, or concealed locations, where Popov could leave messages. But the CIA man performed poorly, was snared in a KGB “honeypot” trap, and was later fired.15 The CIA’s first attempt to establish an outpost in Moscow had ended badly.

In 1956, Popov was transferred to East Germany and resumed spying for the CIA, traveling to West Berlin for meetings with Kisevalter at a safe house. He again proved a remarkably productive agent. His intelligence take included the text of a revealing speech in March 1957 by the Soviet defense minister, Marshal Georgy Zhukov, to troops in Germany about the use of nuclear weapons in war. In 1958, Popov was abruptly recalled to Moscow and interrogated, and his treachery was discovered. However, the KGB kept this under wraps and used Popov to occasionally pass misleading information to the CIA. On September 18, 1959, Popov slipped the CIA a message written in pencil on eight strips of paper and rolled into a cylinder about the size of a cigarette. The message told the CIA what had happened, a courageous last act of defiance by a doomed spy. The message was rushed back to headquarters, where Kisevalter read the penciled Cyrillic on the tiny strips of paper and broke down in sobs. Popov was tried in January 1960 and executed in June by firing squad.

The second breakthrough began to unfold just two months later in Moscow, on August 12, at about 11:00 p.m.

Two American student tourists, Eldon Cox and Henry Cobb, strolled across Red Square cobblestones, still wet from a light rain, heading back to their hotel after seeing a performance of the Bolshoi Ballet, when a man came up behind them and pulled at Cobb’s sleeve, holding a cigarette and asking for a light. The man was of medium build, wearing a suit and tie, with reddish hair showing gray at the temples. He asked if they were Americans, and when they said yes, he began to speak rapidly while looking around to make sure they were not being observed. He pressed an envelope into Cox’s hands and pleaded with him to take it immediately to the American embassy. Cox, who spoke Russian, took it to the embassy that night. Inside was a letter. “At the present time,” said the writer, “I have at my disposal very important materials on many subjects of exceptionally great interest and importance to your government.” The writer did not identify himself, but enclosed a hint that he had once been stationed in Ankara, Turkey, for Soviet military intelligence. He gave precise instructions for how to contact him—with messages in a matchbox concealed behind a radiator in the entrance hall of a Moscow building. He included a diagram for the dead drop.16

The writer of the letter was Oleg Penkovsky, a colonel in the GRU, an imaginative, energetic, and self-confident officer who served with distinction in the artillery during World War II. He was now working at the State Committee for Coordination of Scientific Research Work, a government office that oversaw scientific and technical exchanges with the United States, Great Britain, and Canada and provided cover for Soviet industrial espionage and clandestine acquisition of technology in the West.

The letter was delivered to the CIA, which was suspicious at first. They knew the Soviets had been deeply embarrassed by the Popov case. Was the letter a trap? A decision was made at headquarters to contact the writer, but at the time the CIA did not have a streetwise operative in Moscow. The U.S. ambassador in Moscow, Llewellyn Thompson, was adamantly opposed to the assignment of any CIA personnel to the embassy. Eventually, in the autumn of 1960, an arrangement was worked out to send a young officer from the Soviet division at headquarters to Moscow, expressly to make contact with Penkovsky. The officer did not speak Russian very well. The CIA gave him a code name: COMPASS. He screwed up, drank heavily, and failed to make contact.17

Penkovsky was frustrated. He had written his first letter to the Americans in July 1960, and he spent weeks looking for someone to deliver it. “I stalked the American Embassy like a wolf, looking for a reliable foreigner, a patriot,” he recalled.18 After he handed the letter to Cox on Red Square in August, Penkovsky waited and waited for the CIA to respond. He heard nothing. He tried to pass his information through a British businessman, then a Canadian, without success. He was growing desperate.

Finally, on April 11, 1961, Penkovsky slipped a letter to a British businessman that was addressed to the leaders of the United States and the United Kingdom. The businessman, Greville Wynne, shared the letter with the British Secret Intelligence Service, or MI6, which provided the letter to the CIA. The American and British services decided to work together to run Penkovsky as a spy.

Nine days later, Penkovsky came to London as head of a six-man Soviet trade delegation shopping for Western technology—steel, radar, communications, and concrete-processing techniques. It was a tense time; the CIA’s Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba had just failed. On arrival, Wynne met Penkovsky at the airport, and Penkovsky immediately handed an envelope to him. It included descriptions and diagrams of the latest Soviet missiles and launchers. Later that evening, Penkovsky left his room at the sprawling Mount Royal Hotel on Oxford Street in London and walked to room 360. He knocked on the door, wearing a business suit, white shirt, and tie. When he entered the room, he was greeted by two British and two American intelligence officers. “You know now that you are in good hands,” a rumpled, heavyset American reassured Penkovsky. He was Kisevalter. Penkovsky replied, “I have thought about this for a long time.”

In the conversations that followed, Penkovsky told the American and British officers that his career as a Soviet intelligence officer had gone off the rails, and he was bitter. His father died when he was only four months old, and his mother had told him it was from typhus. But papers had been found about a year earlier showing that his father had served as a first lieutenant in the White Army, fighting against the Bolsheviks, which threw Penkovsky’s loyalty into doubt. He was accused of covering it up. An assignment to India fell through, and he was shunted aside. He loathed the KGB.

On two extended visits to London, first in April and May and then in July and August, and one trip to Paris in September and October 1961, Penkovsky spoke to the British and American intelligence officers for 140 hours in smoke-filled hotel rooms, which produced twelve hundred pages of transcripts. Penkovsky also delivered 111 rolls of exposed film. In Moscow, he used a tiny Minox commercial camera to photograph more than five thousand pages of secret documents, almost all of them about the Soviet military and taken from the GRU and military libraries. Penkovsky was filled with zeal and took risks, once photographing a top secret report right off the desk of a colonel who had momentarily stepped out of his Moscow office.

Not all the conversations with the American and British officers went smoothly. In one of the early sessions at the Mount Royal Hotel, Penkovsky presented a bizarre plan to hold Moscow and the entire Soviet leadership hostage. He wanted to deploy twenty-nine small nuclear weapons in random fashion throughout Moscow in suitcases or garbage cans. The United States was to provide the weapons, instruct him on welding them into the bottom of garbage cans, and provide him with a detonator. With difficulty, he was talked out of the fantasy.19

But Penkovsky took his espionage mission seriously and demonstrated to the CIA how a single clandestine agent could produce volumes of material. When asked if he could obtain copies of the Soviet General Staff journal Military Thought and urged to look for the secret version, Penkovsky asked if the CIA also wanted the top secret version. The CIA didn’t know there was one. Penkovsky provided almost every copy of the journal, in which Soviet generals debated concepts of war in the nuclear age.20 His reports provided critical insights into Soviet intentions during the 1961 Berlin blockade, informed the West for the first time about the existence of the all-important Military Industrial Commission, which made decisions about weapons systems, and provided key technical details of the R-12 medium-range missiles that the Soviet Union sent to Cuba in the fall of 1962, especially the range of the missiles and time required to make them operational. Penkovsky’s intelligence, code-named IRON-BARK and CHICKADEE, was a key ingredient in decision making as President Kennedy stood up to Khrushchev during the Cuban missile crisis.21 Penkovsky’s information on the Soviet medium-range missiles was included in the President’s Daily Brief in the third week of October 1962. Additionally, Penkovsky’s information, along with the first reports from the new Corona spy satellite, debunked the myth that the Soviet Union was churning out intercontinental ballistic missiles like sausages, as Khrushchev had boasted. The “missile gap” didn’t exist.

Penkovsky was, at the time, the most productive agent ever run by the United States in the Soviet Union.22 The CIA and MI6 agreed to pay him $1,000 a month for intelligence worth millions.23 After the meetings in the hotel rooms in London and Paris, the operation moved into a second phase in which Penkovsky was run in Moscow. The British businessman Wynne, who visited the Soviet Union periodically, met with Penkovsky, collecting intelligence and passing it to MI6. But Penkovsky was eager to deal directly with the American and British intelligence services in Moscow.

The CIA was not ready. Ever since the disaster of COMPASS, a replacement officer had been in training, but the replacement pulled out at the last minute, leaving the CIA empty-handed at a critical juncture. “We had an increasingly desperate and very valuable agent out there and no one in a position to contact him,” recalled a CIA officer who was involved at the time.24 The agency also still lacked suitable spy gear for the operation.25

While the Americans had played the preeminent role in the meetings in London and Paris hotel rooms, the British came to dominate the operation in Moscow. According to the CIA officer, “MI6 was able to do what we could not—devise and carry out a cover operational plan for the case.” The British chose Janet Chisholm, wife of the MI6 station chief, to be Penkovsky’s case officer. She met with Penkovsky a dozen or so times, at British embassy receptions and a cocktail party, at the nearly empty delicatessen shop of the Praga restaurant, at a secondhand shop, in a park, and in apartment building foyers, often under difficult conditions, with her three children in tow. Penkovsky passed film cassettes concealed in a box of chocolates for the children. He seemed frenetic and driven; the CIA worried that he was meeting too often with Mrs. Chisholm. When the CIA finally deployed a trained officer to Moscow at the end of June 1962 to work on the Penkovsky case, the officer’s work was short-lived. Penkovsky was last seen by the CIA at a U.S. embassy reception on September 5, 1962, and then disappeared.26

He fell under suspicion by the KGB, which had put Mrs. Chisholm under surveillance. They had drilled a pinhole in the ceiling of his apartment study and put a camera there to monitor him. Another KGB camera in a nearby building photographed him in his apartment. A search discovered the Minox camera, as well as methods for encrypting messages, and a radio receiver he had been given for clandestine communications from the West. Penkovsky was arrested in September or October 1962. He was tried publicly and convicted of espionage, then executed on May 16, 1963.27

At almost the same time that Penkovsky was talking to the American and British officers in the hotel rooms, two more Soviet officers volunteered to become spies for the United States, both outside the Soviet Union. In 1961, Dmitri Polyakov, a Soviet military intelligence officer assigned to the United Nations, offered his cooperation in New York and became a source whom the FBI gave the code name TOPHAT. Then, in 1962, Alexei Kulak, a KGB scientific and technical officer, volunteered in New York to the FBI in exchange for cash. He became the FBI’s source FEDORA. Both TOPHAT and FEDORA were important and valuable assets for the CIA and the FBI at different times in the 1960s and 1970s, but they were largely handled beyond the Soviet borders. In the back alleys of the world, it was possible for the CIA to recruit agents and spies, and to exploit volunteers, but not yet in the very center of the Soviet Union, on the streets of Moscow.

After the loss of Penkovsky, the CIA entered a long, unproductive period in Moscow. A major cause for this was the overwhelming influence of James Angleton, the counterintelligence chief at headquarters. He threw the CIA into a state of high paranoia and operational paralysis. A tall, thin, quirky man, gentle to friends and inscrutable to others, Angleton cut a distinctive figure in owlish eyeglasses, dark suits, and wide-brimmed hats. He lorded over his own autonomous office, keeping his files locked and separate from the rest of the CIA, sitting at a desk piled with dossiers and shrouded in blue haze from chain-smoking. He enjoyed two hobbies, growing orchids and twisting elaborate flies for trout fishing. Over twenty years as the CIA’s chief of counterintelligence, from 1954 to 1974, Angleton created an extraordinary mystique about himself and his work. Secretive, suspicious, and tenacious, he became obsessed with the belief the KGB had successfully manipulated the CIA in a vast “master plan” of deception. He often spoke of a “wilderness of mirrors,” a phrase he borrowed from T. S. Eliot’s 1920 poem “Gerontion,” to describe the layers of duplicity and distrust that he believed were being used by the KGB to mislead the West. In 1966, Angleton wrote that an “integrated and purposeful Socialist Bloc” had sought to spread false stories of “splits, evolution, power struggles, economic disasters [and] good and bad Communism” to a confused West. Once this program of strategic deception had succeeded, the Soviet Union would pick off the Western democracies, one by one. Only the counterintelligence experts, he said, could stave off disaster. Angleton’s suspicions permeated the culture and fabric of the CIA’s Soviet operations division during the 1960s, with disastrous results. Two directors of the CIA, Allen Dulles and Helms, let Angleton have his way. Angleton felt that no one and no information from the Soviet KGB could be trusted. If no one could be trusted, there could be no spies.28

Counterintelligence is essential for any spy agency to prevent penetration from the same espionage methods it uses against others. In the Cold War, that required a combination of outward vigilance, watching every move of the KGB and deceiving it when possible, and inward skepticism, ensuring the CIA was not swallowing any deceptions or double agents. Ideally, counterintelligence went hand in hand with collecting intelligence, yet there has always been a natural tension between them. A case officer might have painstakingly recruited an agent to produce a fresh stream of “positive intelligence,” the fruits of spying, only to find a counterintelligence officer raising questions about whether the source could be trusted. The CIA needed both, but Angleton’s counterintelligence juggernaut became overpowering in the 1960s; everything was labeled suspicious or compromised.

Angleton’s adult life was forged in the world of deception. After graduating from Yale, he became an elite counterintelligence officer based in London for the wartime Office of Strategic Services, the OSS. There he witnessed the astonishing British deception operation against the Nazis known as Double Cross. The British identified German agents and turned them against the enemy, effectively neutralizing Nazi intelligence collection. After running agents in Italy, Angleton returned to headquarters to become the CIA’s chief counterintelligence officer. He believed a massive KGB “strategic deception” was being played out against the United States. His friendship with Kim Philby might have played a role. In the 1950s, the British MI6 officer had been a confidant of Angleton’s. Then, in 1963, Philby was revealed to have been a KGB spy, and he fled to Moscow. The CIA had long suspected Philby, but the confirmation might have been taken by Angleton as more evidence the KGB was on the march—everywhere.

The strongest influence on Angleton, however, was Anatoly Golitsyn, a mid-level KGB officer who defected in 1961. Golitsyn spun a vast web of theories and conjecture that reinforced Angleton’s suspicions of a KGB “master plan” to deceive the West. At the CIA, others called it Angleton’s “monster plot.” Golitsyn said that every defector and volunteer to come after him would be part of the master plan. Certainly, the KGB did attempt deceptions, but Angleton pumped fear to new heights. In 1964, he initiated a hunt for a mole inside the CIA to find what Golitsyn asserted were at least five and perhaps as many as thirty agency officers or contractors who were Soviet penetrations. None were ever found, but several careers were ruined. Among those who came under suspicion was the first Moscow station chief and the Soviet division chief; both were later cleared. When another KGB officer, Yuri Nosenko, defected in 1964, he was incarcerated and interrogated by the CIA for more than three years because of doubts raised about his bona fides by Angleton and Golitsyn.

Over time, Angleton’s suspicions seeped into the CIA’s Soviet division. The poisonous distrust and second-guessing became serious obstacles to espionage operations inside the Soviet Union. Neither potential agents nor positive intelligence could get past him. The Moscow station was small, only four or five case officers, and they were exceedingly cautious, spending a great deal of time preparing dead drop sites—just in case there would be a spy. One case officer spent two years in the Moscow station without ever meeting a real agent. Robert M. Gates, who entered the CIA as a Soviet specialist in 1968 and later rose to become CIA director, recalled that “thanks to the excessive zeal of Angleton and his counterintelligence staff, during this period we had very few Soviet agents inside the USSR worthy of the name.”29

A younger generation of CIA case officers—who joined the agency in the 1950s and chafed under the restrictions created by Angleton—wanted to lead the agency out of lethargy and timidity. Burton Gerber was among them. A lanky, curious boy, he grew up in the prosperous small town of Upper Arlington, Ohio, during World War II. Each morning, he delivered the Ohio State Journal, a morning paper in Columbus, on his bicycle. While his mother made breakfast at 5:15 a.m., he folded each of the hundred papers and tucked them in a sack for his route. He often read the front-page stories from the war. He was thirteen years old in 1946, infused with a spirit of patriotism, and he often wondered what life was like in those distant lands he read about on the front page. He was determined to see for himself. He went to Michigan State University in East Lansing on a scholarship and earned a degree in international relations. He considered joining the foreign service, but in the late spring of 1955, the final quarter of his senior year, he agreed to an interview with a CIA campus recruiter. The CIA in those days was not discussed, nor was much known about it. The recruiter could not tell Gerber anything about the job, but would he be interested? Gerber said yes, took the application back to his fraternity house, filled it out, and mailed it in. Before year’s end, Gerber had joined the CIA at twenty-two years old. After a brief, temporary stint in the army, he was trained by the CIA for espionage work and then sent to Frankfurt and Berlin.30

Berlin was a cauldron of espionage on the front lines of the Cold War. The Berlin Operations Base, known as BOB, sat in the middle of the largest concentration of Soviet troops anywhere in the world. The CIA sought to recruit Soviets as agents or defectors, but it was hard, painstaking work. Meanwhile, one of the biggest operations of the base was technical: a clandestine 1,476-foot-long underground tunnel into the Soviet sector in East Berlin used to place wiretaps on Soviet and East German military communications cables. A huge volume of calls and Teletype messages was intercepted; 443,000 conversations, 368,000 of them Soviet, were transcribed by the United States and Britain. The wiretaps worked from May 1955 until uncovered in April 1956.31

Gerber had been taught the traditional methods of handling human espionage agents—finding and filling dead drops, handling letters with secret writing, sending and receiving signals, and making surveillance detection runs. In Berlin during the 1950s, the common method for espionage was to coax sources from the East to come to a safe house in West Berlin for debriefing, as Kisevalter had done with Popov. It depended on the source’s having freedom to move from East to West, which was possible until the Berlin Wall went up in 1961. A whole new set of obstacles then confronted the intelligence officers: how to run agents at a distance. The CIA still had little experience in the closed societies of the Soviet bloc. The agency’s thinking at headquarters was dominated by veterans of the Office of Strategic Services, the World War II intelligence agency, who had carried out daring paramilitary exploits during the war but believed that impersonal methods, such as dead drops, were safest.

A dead drop is a method of exchanging messages and intelligence in a secret location, known to the agent and the handler, who leave materials and pick them up from the concealed spot but never see each other. To the new generation of officers who joined the CIA after the war, the dead drop seemed to be the epitome of caution. They were restless and impatient and began to innovate and experiment with new methods. The Berlin base became a laboratory for running spies on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Instead of just inviting agents to a safe house, the officers created more imaginative techniques for espionage to penetrate forbidden zones.

Fortuitously, Angleton’s suspicions did not extend to Eastern Europe. He didn’t seem to care or pay much attention, although the Soviet satellite states were setting up secret police organizations modeled on the KGB and its predecessors.32 The back alleys of Berlin, Warsaw, Prague, Budapest, Sofia, and other cities of Eastern Europe became a proving ground for younger CIA case officers. They invented new ways to conduct espionage in “denied areas,” as the CIA called them. The methods were important, but even more significant was the mind-set. Gerber had been inspired to do the most important job of the day, which was to fight communism and the Soviet Union. He and his classmates, on their first tours abroad, did not want to sit in their chairs. They were not intimidated by the Iron Curtain. They had chosen espionage as a career and disdained passivity. Gerber always disliked the term “denied areas.” Denied to whom? Not to him, nor to his classmates.

Not to Haviland Smith, either. When he arrived at the Berlin base in 1960, he was full of ideas and became a pioneer in the new thinking that he had first developed in Prague.

A graduate of Dartmouth, Smith served in the Army Security Agency as a Morse code and Russian-language intercept officer from 1951 to 1954 and was later in the graduate program in Russian studies at the University of London, where he did a few odd jobs for the CIA. Smith had a very high language aptitude and spoke French, Russian, and German. He joined the CIA in 1956 and was selected for a tour in Czechoslovakia. While he was deep in language training, headquarters suddenly asked him to take over as Prague station chief in 1958. His predecessor wasn’t particularly active and left abruptly. When Smith arrived in March, he had functioning Czech-language ability but little preparation for the kinds of clandestine operations he wanted to undertake. He hadn’t been trained in the tradecraft of espionage—how to mail secret letters, select and load dead drops, detect and deal with surveillance, or conduct an agent meeting—in a hostile, surveillance-heavy environment. Smith would have to figure it out for himself.33

Smith discovered there were dozens of sophisticated radios in the Prague station, and his army intercept experience proved useful. He found the radio frequency used by the Czech security service in their surveillance vehicles monitoring the U.S. embassy and was able to break their voice codes. If Smith had to put down a dead drop or mail a letter, he turned on the radio first, then ran a tape recorder to capture the broadcasts. He put down the drop or message, then went back and checked the tape. If he was under surveillance while filling the drop, he aborted the operation. If there was no evidence of surveillance, he signaled the agent to pick it up. “Prague was a perfect place for the kinds of operations we were contemplating,” he recalled. “A beautiful old baroque city, it was untouched by war. It was full of narrow, old streets, arcades, and alleys.” Through trial and error, Smith found that most of the time he was under surveillance. Once, he thought he was free but discovered he was being watched by twenty-seven different vehicles. He was shocked and became convinced that whatever espionage he could carry out would have to be done under surveillance. He just could never assume he was free. This was an important early lesson for working in “denied areas.”

Smith began to experiment. He sought to establish regular, observable patterns of behavior that would lull the surveillance teams into complacency. He became a slow, careful driver with the purpose of convincing the Czech surveillance that whenever he went out, on foot or in a car, they already knew what he was up to and left him alone. He went to get a haircut at 10:00 a.m. every other Tuesday, then returned directly to the office, driving slowly. After six months, he realized that no surveillance was on him for the haircut ride, so long as he wasn’t away more than forty-five minutes. Smith always drove his babysitter home each evening, a forty-minute ride. After a while, the surveillance tired of that, too. Smith had created two opportunities for operational activity—a gap—and he might be able to squeeze in the time for a mailing, a dead drop, or something else. In those rigid, careful routines, Smith discovered a behavior of the secret police that had not been realized before. They could be lazy, orthodox, and conventional. The illusionist might deceive them.

Even with this knowledge, however, Smith was restless. The patterns might create a gap, but they were still too rigid. He wanted more flexibility, to be able to carry out a headquarters instruction on the shortest possible notice even when under surveillance. This led him to push the concept of the gap even harder. He found that it was possible, walking or driving the back alleys, to create momentary visual blackouts. He could disappear for a very brief period in a way that would seem normal to the watchers and, if done properly, would allow him enough time to make a brush contact, mail a letter, or put down a dead drop while completely out of sight. The idea was simple: he turned corners. When he was being followed on foot, two brisk right turns around a block would string out the surveillance to the point where he would be completely out of sight from the moment he turned the second corner until the lead watcher caught up and came around the same corner—maybe only fifteen to thirty seconds. That was enough.

Smith also perfected the concept of a brush pass, in which the agent appears at just the right moment in the gap. The agent brushes by the case officer, delivering or accepting a package, then escapes. The secret police would never see the agent on the other end of the brush pass if it worked right; the agent would be gone in a flash. Much depended on finding the right location, with jutting corners to block the line of sight of surveillance and a fast escape path for the agent.

Smith was sent to Berlin next. It was a different kind of city, more spread out, but he still operated in the gap and under surveillance. His ideas suggested a real change was possible from the old days: the ability to run espionage operations in the pressure-cooker environment of closed zones. At the suggestion of headquarters, Smith began to train others in Berlin on his new methods, building in everything he’d learned about working “in the gap.” For years that followed, moving “through the gap” became a watchword and a trusted method for CIA case officers.

In 1963, Smith returned to the United States and set up a course for officers heading to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union that incorporated the new tradecraft. But he found there was still caution and timidity in the CIA leadership. Smith was asked to train a Czech intelligence source in the United States. The agent absolutely refused to use dead drops because the incriminating secret messages and film would be out of his hands—and could potentially be discovered by the Czech secret police. When Smith showed him the brush pass method, the agent readily agreed to use it, because he would put his material directly into the hands of the CIA. At headquarters, a request was made to Helms for permission to use the technique operationally in Prague. Without even asking questions about it, Helms refused, saying he had “sores all over his ass” from the Penkovsky case and was not getting involved in “that sort of thing” again, Smith recalled. The Czech agent went to Prague without permission to use the brush pass, and a year went by. Smith hammered away at headquarters, seeking approval. A steady stream of valuable agents was beginning to show up in Eastern Europe, and Smith felt the dead drop routines were completely inadequate.

In 1965, Helms agreed to an experiment. He sent his deputy, Thomas Karamessines, to a demonstration of the brush pass. Smith set it up in the lobby of the grand old Mayflower Hotel in downtown Washington. In the demonstration, the brush pass was carried out so deftly that Karamessines missed it. The key had been sleight of hand: a case officer dramatically shook out a raincoat with his left hand just as he handed off a package to Smith with his right. Karamessines saw the raincoat but not the package. Smith had learned this technique from a professional magician. The next day, Helms approved the use of the brush pass in Prague. The Czech agent subsequently passed to the CIA hundreds of rolls of film. The brush pass, with modifications, was later expanded into all of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.