Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

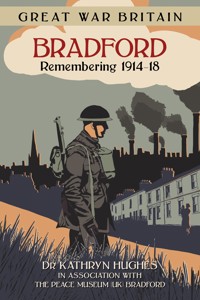

The First World War claimed over 995,000 British lives, and its legacy continues to be remembered today. Great War Britain: Bradford offers an intimate portrayal of the city and its people living in the shadow of the 'war to end all wars'. A beautifully illustrated and highly accessible volume, it describes local reaction to the outbreak of war; the increasingly difficult job of recruiting; the changing face of industry and related unrest; the growing demands on hospitals in the area; the impact of war on women and children left at home; and concludes with a chapter dedicated to how the city and its people coped with the transition to life in peacetime once more. The Great War story of Bradford is told through the stories of those who were there and is vividly illustrated with evocative images.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 249

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Timeline

Foreword

Acknowledgements

1 Outbreak of War

2 Raising the Troops

3 Adjusting to War Work

4 Restrictions and Relief

5 Civilian Life at Home

6 Caring for the Troops

7 War, Near and Far

8 Peace, and Return to Life as Normal?

Postscript – Legacy

Copyright

TIMELINE

FOREWORD

The scale and scope of the conflict would have been inconceivable in an earlier age. What we call the first ‘world’ war reached, in some form or other, to most parts of the globe. It also permeated deep into every corner of British society. This was total war in a way that an imperial nation, used to fighting its wars at arm’s length, could never have anticipated. Nowhere could escape, however far from the trenches of France and Belgium. Bradford, a proud, successful Yorkshire city with a radical, independent streak, would be caught up in this all-encompassing war and the lives of every citizen would be changed by the conflict forever.

In this comprehensive and thoroughly researched insight into Bradford lives in 1914–18, Kathryn Hughes takes us into the heart of wartime society. Who were the people who lived and worked in this city? What were their concerns, passions and interests? What was the shape of their lives, their homes, and their work? And how did that change as the young men started to go away? There were spaces in family life, gaps in the workplace temporarily and, too often, permanently. How did the city rally round to the common cause?

Or was it such a common cause? What about those who protested about the war, who did not believe it to be justified, or who wanted negotiations to end it as soon as possible? That nonconformist, independent streak in the city, and the rise of the Independent Labour Party, meant that the war was not without its critics. What about those individuals who courted public disapproval and scandal by refusing to be conscripted into the army, by becoming conscientious objectors? And what about their families, facing public disdain by association?

We are used to hearing of men’s stories from the front, but what of the women’s stories, still as yet disenfranchised women whose lives were overturned as the certainties of pre-war home life were cast aside in factory and mill and social organising?

And how did they, and everyone else, cope when their young men started to return home, wounded or sick, physically and mentally, shadows of the enthusiasts who had succumbed to the euphoria of the recruiting campaigns? In particular, how did the city handle the trauma when the Battle of the Somme decimated the Bradford Pals Battalion, hundreds of local young men sacrificed in a single day? In a tight-knit community, few were left unscathed by grief and mourning.

This is the society that Kathryn Hughes explores: ordinary citizens caught up in a war far away which transformed their city, their neighbourhoods, and their homes. What choices did they have? What choices did they make? And how were they affected by the decisions of others?

Perhaps this is not only history – an exploration of the past; as we consider the choices of our forebears, it may inspire us to think on the choices we make today in our own lives. What do we value most in our family, our society, our nation? All too clearly we see the cost of war; how can we make a difference today and make our choice for peace?

Dr Clive Barrett,

Chair, the Peace Museum, Bradford

2015

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been written if it were not for the support and encouragement of Sue Caton, Senior Information Manager, Bradford Local Studies Library. The staff and management of West Yorkshire Archive Service have also been invaluable in allowing me access to their records. Thanks are also due to those individuals who have taken the time to proofread copies of the text or provided images for the book. Finally to family and friends whose support has been invaluable from the outset.

1

OUTBREAK OF WAR

Bradford to-day very much resembles a garrison town, for all manner of troops are being mobilised here, and in addition to the hundreds that have already left, we are housing large numbers of His Majesty’s Troops.

(Bradford Daily Telegraph, 7 August 1914.)

The Build-up to War

Bradfordians were enjoying the summer of 1914. Record numbers had attended the Yorkshire Show which was held in Bradford on 22–24 July 1914, the highlight of which was the launch of the ‘Great Yorkshire Show Air Line’. It was said to be the first airline service in Great Britain flying between two cities, Bradford and Leeds, to a timetable – although this was hampered by the weather on the second and third days of the show.

People were looking forward to the August Bank Holiday weekend and, although the threat of war reduced the exodus of the wealthy to the Continent, neither that nor bad weather prevented holidaymakers pouring out of the city to the seaside on Saturday, 1 August.

The following day, however, railway companies started cancelling excursions and bookings as their trains were requisitioned for military use, and even local day trips were down by 75 per cent.

The speed at which the international situation developed came as a shock to many; every day brought news of a new ultimatum or sensation. Visible signs of the war came, as first foreign and then home reservists started to depart the city in the midst of returning holidaymakers.

The first of the Bradford reservists left the city on 3 August. The following day, the last of the foreign reservists left Bradford from the Exchange Station, including a party of fifty German conscripts (many of whom were well-known Bradford tradesmen) who bade tearful goodbyes to their wives and children. The French consul in Bradford, Mr Claude Lievre, who had lived in the city for nineteen years, was kept busy getting his compatriots away before himself leaving to join his battalion in France.

The Yorkshire Show came to Bradford, 22–24 July 1914. (West Yorkshire Archive Service)

Food prices also started to soar as those who could afford to do so were preparing for the worst-case scenario by bulk buying and hoarding supplies. This caused a run at the Bradford grocers who found it virtually impossible to supply the abnormal orders. The Lord Mayor of Bradford sent out an appeal for calm, quoting a report from the Minister of Agriculture stating that there were ample supplies in the country and that there was no need to pay ‘panic’ prices. He pointed out that bulk buying by those who could afford it was having a detrimental effect on the poorest in the city who could not afford to pay the inflated prices; they had little chance to save money in normal times, and in most cases had no out-of-work pay to fall back on.

4 August 1914 - War Declared

The declaration of war sent shockwaves over the city; a mix of excitement at the scenes being witnessed in the city, concern for loved ones already engaged in the military and uncertainty about the financial situation and jobs at home.

Declaration of War carved into a stone on the moor above Wilsden. (Peter Hughes)

The government had passed a bill to extend the bank holiday for a further three days to prevent a run on the banks. The plan was that general industry would not be stopped. However, concern over access to capital; orders and deliveries cancelled; doubt as to whether wages could be paid; the hoarding of gold; withholding of payments; disruption to supplies from overseas; foreign debt, and the collapse of the export market caused great difficulties to many industries.

The Bradford Chamber of Commerce convened a special meeting on 5 August calling for trades to unite and assist each other during these uncertain and difficult times, and continued to hold many meetings in the following days.

Trade associations from a range of sectors across Bradford called for businesses to minimise the hardship to their employees and to do all in their power to keep workers employed. Many, like Lister & Co. Ltd, did this by going on short time rather than shutting completely. Still, Bradford’s wool trade practically came to a standstill, but engineers and iron founders also found they had to close their works temporarily or indefinitely.

Other places of business were opened, but there was little business done in them, instead crowds gathered in the city waiting for news. Around 5,000 men in the city were still thought to be out of work or working only a day or two per week.

BRADFORD REGIMENTS IN AUGUST 1914

REGULAR ARMY – Army Service Corps – headquarters Bradford Moor Barracks.

TERRITORIAL ARMY – originally enlisted for home defence in the UK only, both battalions were part of the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division.

6th Battalion Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) (Territorial Force) – headquarters Belle Vue Barracks.

2nd West Riding Brigade Royal Field Artillery (Territorial Force) – headquarters Valley Parade Barracks.

It didn’t take long to fill up the city’s battalions to their full strength with men of high medical and physical standards, who had enlisted in order to continue to support their families with the promise of army pay and separation allowance. They were sworn in and entered straight onto a course of drilling.

Those that were employed when they enlisted were more fortunate, as many businesses declared that they would hold their workers’ positions open for them and some, for example Bradford Corporation, Bradford Dyers’ Association and Lister’s & Co. Ltd, even promised to supplement their army pay.

Garrison Town

Both of Bradford’s Territorial units had barracks just off Manningham Lane, at Belle Vue and Valley Parade, and the area became a centre for great military activity. The 2nd West Riding RFA (Royal Field Artillery) were at camp in Marske until they were told to strike the camp and return home on Sunday, 3 August. Then they, and the men of the 6th West Yorks., reported to their barracks and awaited instructions.

On 4 August, the majority of the 6th West Yorks. were on parade and were informed that they were under martial law. Each would receive a £5 gratuity for joining their unit, and separation allowance would be paid to their wives and children. Those who lived within a mile of the barracks were permitted to return home at night. The men who lived further away had to bivouac in the barracks, some in the drill hall, others in Belle Vue, Carlton Street and Green Lane schools with just a blanket for a covering and a kit bag for a pillow. Thankfully they were offered the use of the corporation’s baths for free!

Scene outside Belle Vue Barracks. (Bradford Libraries)

Mobilisation at Midland Station. (Bradford Libraries)

Large crowds assembled at the Army Service Corps Barracks at Bradford Moor expecting to see the arrival of men parading in great numbers. However, as the reserves arrived from across the country they did not turn up en masse, and once they had undergone medical examination they were rapidly drafted off to different parts of the country where their services were required. However, there were 1,000 ‘sturdy ploughmen’ of the Yorkshire Wagoners’ Special Reserve who made a stir on their arrival and were stationed at the barracks prior to being mobilised.

The train stations were kept very busy with the constant flow of reservists and Army Service Corp troops in and out of the city. The trams were also severely affected when ninety-four reservists in the department suddenly left the city in the first few days of the war, causing a large number of services to be withdrawn at very short notice and resulting in considerable disruption in the city. However, the scheme to manage sudden emergencies kicked in and conductors who were trained drivers took the place of those called away, the conductors being replaced from the male tram cleaners, thus avoiding prolonged disruptions.

Lister Park was shut to the public after 6 August, under armed guard, as an almost constant stream of horses as well as the guns, ammunition and other wagons of the Army Service Corps and Territorial units arrived. On 8 August, before the first week of war was over, the 6th West Yorkshire (Territorials) had made up their numbers to twenty-nine officers, 979 men, fifty-seven horses and the necessary equipment. They reported to York that they were at full strength and were the first Territorial unit to do so.

They were also the first of the two Bradford Territorial battalions to leave the city, departing from their barracks at 6 a.m. on Monday, 10 August and marching to Midland Station. Due to the lack of warning and the early hour, their departure was relatively quiet. Two special trains were put on to convey the soldiers and horses, the first leaving at 9 a.m. and the second, half an hour later. The lord mayor and chief constable were present to see them off, and as word started to spread, crowds gathered on railway embankments to wave them off on their journey to Selby.

War Horses - Mobilisation of the 2nd West Riding Royal Field Artillery Territorials

The Royal Field Artillery (RFA) Battalion needed to acquire large numbers of horses to pull the heavy guns and ammunition. However, as they didn’t have a parade ground at their Valley Parade barracks they were given the use of Lister Park to drill and prepare their guns and horses, as well as the Midland Hotel to use as headquarters. The 7 August saw the arrival of the 5th Battery from Halifax and the 6th Battery from Heckmondwike, followed on the 8 August by 137 heavy draught horses purchased by the army. It was soon realised that the headcollars and harnesses would not hold the heavy draught horses at night and stronger ones were ordered.

Bradford Corporation tramcars hooking up the gun carriages. (West Yorkshire Archive Service)

When the horses arrived they were inspected by military and extra civilian vets; those considered unsuitable for stabling in the open or in tents in the park were taken to sheds in the playgrounds of Belle Vue and Carlton Street Schools or to Bradford Carriage Company’s depot in Manningham Lane. The horses were then branded with a government broad arrow on the near fore foot, with the County Association Consecutive Number on the off and near fore foot, ‘RFAT’ on the off hind foot and ‘WR’ proceeded by the battery number, or ‘AC’ (Ammunition Column) on the near hind foot.

On 10 August (the sixth day of mobilisation) collecting parties were sent out to bring in horses from collecting stations around the district:

Keighley –

71 (2 rejected)

Leeds –

95

Halifax –

42

Dewsbury –

26

Bradford (two stations) –

not forthcoming

Selby –

28 sent by rail to remounts at York

The allotted number of horses were not forthcoming from Bradford. On 12 August, twenty-six of the 573 horses had been provided at short notice by Spen Valley but they were still fourteen short. They put the problems down to ‘undisciplined civilian purchasers who seemed to have no system’ (Bradford Volunteer Artillery Mini Archive). Some of the horses were for riding, while heavy horses were required to pull the twelve guns, seven carts and nine wagons for small arms ammunition (SAA), twenty-four ammunition wagons, twelve wagons for guns, eleven wagons for baggage, four water carts and a medical equipment cart.

GERMAN PRISONERS OF WAR

On 7 August fifty Germans were taken as prisoners of war, the majority being released on parole by 13 August. The remaining twenty were removed to York Castle on 16 August. The Register of Aliens, completed on 20 August, contained a much larger number of German or Austrian subjects than the 500 originally estimated.

Aliens on parole, or deemed unlikely to be a threat, were banned from using telephones or motor cars, and all correspondence was subject to careful scrutiny. They were not allowed to leave the town without a permit from the police and anyone without the permit in their possession was liable to be arrested.

More difficulties with the strength of the harnesses and in obtaining forage caused delays, and the horses, not surprisingly, were unsettled by their new environment and duties, being branded and the noise of the troops and heavy equipment. So much so that there was a stampede in Lister Park the evening before mobilisation; the horses broke free of their lines and careered wildly over flower beds and bowling greens, spooked by their strange surroundings.

Early on the morning of 13 August, just three days after the 6th West Yorks., they were ready to depart, causing much more of a spectacle, even though half of the guns had already been sent off in advance by train, and one or two horses were still not recaptured. This was partly due to trams being used to tow the heavy guns for the first time ever, thanks to a special coupling made by the Tramways Department.

They departed at 5 a.m., and the journey was not an easy one, with twists and turns, dangerous descents and steep uphill climbs, but thankfully none of the carriages toppled or broke free. It spared the horses much heavy work and allowed the spirited ones to calm down and get used to their new role before they took over at Drighlington and completed the journey.

SHORT-TIME WORK: LISTER & CO. LTD

‘In view of the impossibility of shipping our goods to a large number of our customers and for reasons stated below it has been decided at a full meeting of directors to put the whole of the works for the present on short time beginning next week. The hours will be as follows: Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday 9 a.m.–1 p.m. and 1.40 p.m.–4 p.m. The works will be closed on Saturdays and Mondays. Our object in taking this step immediately is to spread the work and wages over the longest possible period.

It will be our endeavour to employ the full complement of workpeople, so as to distribute as fairly as possible the wages available. Unfortunately, many of our necessary supplies come from the continent and consequently this will eventually cause a stoppage of certain sections. We wish to impress upon all our workpeople the absolute necessity of affecting every possible economy in their expenditure with a view to meeting whatever difficult times the future may bring forth.’

(Bradford Daily Telegraph, 7 August 1914.)

Lister & Co. Ltd, Manningham Mills. (West Yorkshire Archive Service)

The troops then marched off with their 300 horses and equipment to Midland Station where the main personnel train awaited their departure to Doncaster at 8.45 a.m. With its long line of horse boxes it stretched beyond the platform’s end. However, an even longer train was yet to come; the longest in the history of the station. Comprising ordinary carriages, gun trucks and horseboxes, it was estimated at ¼ mile long. The Halifax 5th Battery boarded this train, and departed at 10 a.m. Amazingly, it only took them forty-five and thirty-five minutes respectively to entrain. They were seen off by the lord and lady mayor.

It took twenty men from the corporation’s Parks Committee two days to return Lister Park to order after the stampede and it was reopened to the public on 15 August.

A Father's Concern

The father of one of the Territorials wrote to the Bradford Daily Telegraph to complain that his son, who was a private in the 6th West Yorks., had written to tell him that all the men were asked to volunteer for foreign service ‘if necessary’ and that most (if not all) agreed to do so. He states:

This is very serious news for parents with sons in the Territorials and is not quite playing the game. The Territorials were formed for the distinct and only purpose of defending our country from invasion and every man was enlisted on this understanding; on any other understanding the great majority would not have joined, nor would parents have allowed them to do so. I am proud that my son should have entered the service, and I am fully prepared for whatever this may entail in the fulfilment of his accepted duties and the defence of his country. But compulsory Foreign Service is altogether different matter, and I protest most emphatically against the action of the military authorities in demanding this. They call it ‘voluntary’; but it is not voluntary. When men under such circumstances are ‘asked’ to volunteer it is impossible to refuse, and the request becomes a command. It is certain that if left to the really voluntary action of the Territorials many who are merely boys would not take such a step without consulting their parents. This has been made impossible and I consider that there has been a gross breach of faith, and that the men have been tricked into accepting, and that their parents have been treated most hardly and unfairly.

(Bradford Daily Telegraph, 15 August 1914.)

German Aliens and Spy Scares

Bradford had a large well-respected German community. Many were prominent businessmen in the city, and two (Charles Semon and Jacob Moser), had previously been mayors. Many had become naturalised British subjects. However, the bureaucracy, cost and the need for evidence of residence in the UK for more than five years, meant that others had not yet completed the process and were now considered to be enemy aliens. Many sought the help of Sydney Neumann, a British-born solicitor (who later changed his name to Newman), and Augustus Ingram, the US consul in Bradford, who temporarily assumed the protection of the interests of German subjects in the Bradford district.

The 7 August saw the start of a procession of foreigners to the town hall to register under the new Aliens (Restrictions) Act 1914. This led to a long series of alien arrests; German prisoners of war were handed over to military authorities and taken to Bradford Moor Barracks, which acted as a military prison. The barracks, which would normally house 600 troops and had been deemed as unfit for human habitation many years before, now provided accommodation for nearly 1,000 troops as well as fifty prisoners of war. To cope with the numbers, stables and outhouses were used as sleeping rooms with the ‘ploughmen’ sleeping on the bare floor and sharing a blanket.

Bradford Moor Barracks. (Bradford Libraries)

In contrast, the German prisoners were shown every consideration; they were provided with a comfortable bed and were mostly accommodated in the officers’ quarters. They were allowed to have food supplied by friends from outside, and they had time set aside for recreation, etc. As long as they behaved decently there was no undue supervision. When Ingram went to see them he received no complaints of their treatment. There was one scare that a German prisoner had escaped, however, the barrack-breaker was found to be a ploughman who had climbed the wall to enjoy a night in the city!

Location of the 6th West Yorks. and the 2nd RFA barracks on Manningham Lane. (Bradford Libraries)

Rumours were rife, as people speculated about individuals’ alien status. But, although there were cases of spy scares and broken windows, many were unfounded, drunken misdemeanours or schoolboy pranks. The wild speculations as to citizens’ alien status died down in a few weeks; there was no mass anti-German rioting or high-profile arrests of spies. Even in neighbouring Keighley, the fact that rioters attacked German pork butchers’ shops in August has to be set against the background of a very long ongoing strike and general unrest in the town.

There were many calls for restraint and considerate treatment of naturalised Germans, including one by the lord mayor, Alderman John Arnold. Sidney Neumann also expressed concern for Bradford German families who were starting to struggle financially:

Remember these poor people who have lived amongst us as friends for many years are in no way responsible for the war, and there are many ways in which kindly neighbourly assistance may be given to them which will be remembered gratefully in years to come.

(Bradford Daily Telegraph, 12 August 1914.)

Many naturalised or British-born Germans felt alienated. Some publicly set about helping the war effort to demonstrate their allegiance to the country, while others rushed to change their names by deed poll, and painters were kept busy changing the signs over the shop doors of almost all of the German pork butchers before the month was out. One of the first to change his name by deed poll, on 12 August 1914, was the proprietor of the Alexandra Hotel who changed his name from Frederick George Schutz to Sterling (London Gazette, 28 August 1914).

Motor Volunteers and Scouts

The Bradford Automobile Club issued an appeal for the loan of motor cars for military use, and hundreds of offers were received. In addition, volunteer motorcyclists were called up for service with the army. They were required to enlist for one year or as long as the war continued and were paid 35s weekly, with a bounty of £10 to each man approved and a further £3 on discharge.

However, some of the men who volunteered returned home to Bradford a few days later as a protest about their treatment:

It is alleged that the volunteers are required not only to place themselves entirely at the disposal of the authorities and submit to military law – which of course they are willing to do – but they are expected to provide their own petrol and board and lodging for themselves and accommodation for their cars or cycles. As this would entail very considerable expense entirely apart from the loss which they are already sustaining by giving their services the volunteers feel this is too much to expect of them.

(Bradford Daily Telegraph, 12 August.)

The Bradford Boy Scouts were soon employed helping the military as despatch riders, and guarding the guns of the Bradford Artillery at Lister Park, while others were in the service of officers at Belle Vue Barracks and the Midland Hotel, the headquarters of the artillery officers.

The Scout masters came up with a scheme by which to provide their services to the authorities. They collated a register of around 200 Bradford Scouts (over 14 years old) which included details of each Scout’s average earnings, qualifications and times they were available. They offered services including carrying messages, guarding buildings, distributing food and making enquiries, while younger boys were utilised for other duties such as selling tickets for fundraising events. All applications for assistance were considered by the executive committee and, with the government officially recognising the Boy Scout uniform as that of a public non-military body, it put them on equal standing with organisations such as the St John Ambulance Brigade.

Before long they decided that it wasn’t satisfactory to have the boys waiting outside their small headquarters at No. 1 Manchester Road, and the corporation offered them the use of bigger premises at No. 141 Manchester Road, where four or five Scouts were in attendance every day.

A Fortnight in ...

Two weeks later, the first war orders had started to trickle into the city for khaki uniforms, blankets and for tons of the explosive lyddite. Other businesses started to recognise that the war could provide business opportunities, as German goods were unable to leave Europe and they could cash in on their market. Many dyestuffs, including khaki, were almost exclusively manufactured in Germany prior to the war and work started to develop substitutes. Bradford Corporation was also encouraged by the government to identify work that could be put in hand or accelerated to provide additional employment, for example, starting the tender for the construction of open-air baths at Lister Park.

RIFLE RANGES

Rifle ranges started opening up around the city. The Bradford Municipal Officers’ Guild rifle range, based at the Hall Ings tramway depot, opened at night. It was staffed by six instructors and each man paid 2d for eight rounds. Demand was high and as many as 800 rounds were fired each night.

The third week of the war fell over Bowling Tide, the Bradford holiday week when most of the mills (with the exception of Lister & Co. Ltd) shut down and people holidayed at the seaside. Excursion tickets started to be more widely available, and advertisements from the seaside towns tried to reassure and encourage the tourists to visit. However, with the prospect of short-time work lasting six months or more, people were carefully managing their money and, unsurprisingly, many chose to stay close to home. Musical concerts and other events were hastily used to raise funds for the Lord Mayor’s War Relief Fund and other distress funds.

‘BILLY’ MOON - ONE OF THE FIRST RESERVISTS TO LEAVE THE CITY - 3 AUGUST 1914

‘Billy’ William Edward Tunstall Moon was born in Bolton, Lancashire, and had served in the Royal Navy but, at the time of the outbreak of the war, he was a lift attendant at the General Post Office. On arriving at work at 7 a.m. on 3 August, he and two other postmen had official government envelopes placed into their hands. They had been called up as naval reservists. Billy promptly left his workplace and returned to his house on Draughton Street to put on his uniform and gather his kit and to tell his wife Mary Ann and 4-year-old son Norman. He returned to Midland Station to catch the 10.30 a.m. train with four other naval reservists and, on being met by a crowd of 100 postmen, received a mighty send-off amidst returning holidaymakers. They were lifted shoulder high to a chorus of ‘Rule Britannia’ and the national anthem and the men were carried to their train. Tearful farewells were said to wives and families with cries of ‘We shall soon be back’ from the sailors, who were in the best of spirits.

Billy was on board the cruiser HMS Creesy which, along with its sister ships Aboukir and Houge, was attacked by submarines on 22 September 1914. The Creesy had already sent all her lifeboats to help those on board the Aboukir when it too was hit. Billy was one of the survivors and returned home on the 26 September, less than two months after he left. He said: