9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Black Magick Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

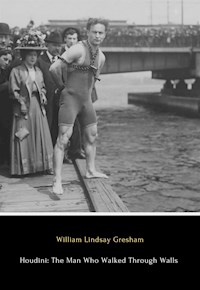

No magician has captured the imagination of the world as did Harry Houdini, his very name a byword for stunning, amazing escapes. In this authoritative biography, acclaimed author and noted psychic skeptic, William Lindsay Gresham details the life of the great man. The strands of Houdini’s life are chronicled in rich detail; the stage illusions and their invention, his private life as he traveled the world, and Houdini’s passion for exposing the frauds and scams of the ‘psychic’ world. Houdini’s legendary illusions are explained and give a fascinating insight into their construction, created with simplicity that is the essence of true genius.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Houdini

William Lindsay Gresham

Published by Black Magick Books, 2022.

Copyright

Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls by William Lindsay Gresham. First published in 1959. Revised edition published by The Black Magick Press, 2022. Footnotes ©Black Magick Press, 2022. All rights reserved.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Prologue—The Shaking Tent

1 - Discovery by Gaslight

2 - The Book of Revelations

3 - The Brothers Houdini

4 - Magic Island

5 - A Crowded House

6 - A Brace of Turkeys

7 - How Broke Can an Act Get?

8 - The Beckoning Ghosts

9 - Jail Break

10 - In Handcuffs and Chains

11 - The Way to Get Dough Is to Ask for It

12 - Young Samson

13 - Underwater

14 - In the Name of the Kaiser

15 - The Impregnable Box

16 - Grave Matters and an Impatient Throng

17 - The House of Mystery

18 - The Big Time at Last

19 - Jail Cells and an Icy River

20 - Challenge and Response

21 - The Miraculous Milk can

22 - Quick Study Connoisseur

23 - The Aeronaut

24 - Shower of Gold

25 - Darkness and the Deep

26 - Through a Brick Wall

27 - Elephants and Eagles

28 - A Grim Game

29 - The Knight's Tale

30 - Movie Star or Bust

31 – “Spooks-a No Come!”

32 - The Blond Witch of Boston

33 - Dreams Come True

34 - Spoiled Egyptian

35 - The Final Challenge

Epilogue - Telegram from Heaven

Further Reading: Pistol Pete, Veteran of the Old West

Prologue—The Shaking Tent

If man has an instinct stronger than self-preservation it is the instinct to escape from bondage—“liberty or death!” Cherished among folk heroes are the liberators: Moses and the Maccabees, Garibaldi and Bolivar. And down the years the adventures of great prison-breakers have made pulses race: Baron Friedrich von der Trenck, indefatigable digger of tunnels from the dungeons hi of Frederick the Great; Henri de Latude, who dangled his way precariously out of the Bastille down a rope ladder several hundred feet long, woven from linen threads. Such tales stir the soul as with the voice of a trumpet. But they are tales, at best, conveyed by the printed word. Then at the turn of the twentieth century there arose from the ranks of obscure music-hall magicians a man who captured the imagination of two continents and held the limelight firmly focused on himself for twenty years. He did it by hammering out a brand-new form of entertainment in which he acted out the dream of every man—escape from bonds by magic. Great as he was, his new art did not burst full formed from his own genius. It had a long and fascinating history of gradual growth. . . The art has always engaged us; perhaps it touches us more deeply than we know. Glance first at these scenes. They are a part of our fabulous history of magic—and of the man who made its practice his life.

In the days before the white men came with their iron skins and fire sticks, the nation of the Anishinabeg lived in the lands Longfellow described as being “by the shining big sea water.” The Anishinabeg (other tribes called them Ojibwa) were great hunters, great fishermen in their big sea water—Lake Superior—and great warriors. But when decisions affecting the nation, a matter like war with the Fox tribes to the south, came before their councils, the elders sought advice from another world. A circle drawn on the ground in the place-of-talking symbolized, for the council, the horizon on which rests the sky. Five stout saplings, trimmed of branches, were sunk three feet into the ground; earth was then packed hard around the saplings' base. A covering of moose hide draped the place of invocation so that no profane gaze could spy on sacred mystery. Then the magician came forward to stand in the firelight, naked save for the pelt of a beaver worn like an apron and, on his head, a medicine bonnet bearing the stuffed heads of an eagle, owl, crane, and loon. He saluted the four winds with proper ceremony. At last, he began to call down the spirits of the ancient great from their ghost dance in the northern heavens. One of the tribe's bravest young warriors, known to be an expert at confining prisoners with strips of hide, then came forward.

The magician held out his left wrist so that hide might be knotted firmly about it; he crossed his hands behind his back and the right wrist was tightly tied to the left. Other strips fastened his ankles. Though he was helpless now, his feet were drawn up and lashed to his wrists. Solemn braves lifted the trussed man and carried him into the tent, left open at the top to admit the spirits of the air. Hoot of the owl, gabble of the loon. From the hide-walled enclosure, only wide enough to allow the jackknifed magician to lie across it, rose a chorus of unearthly sounds. The watching crowd moaned as ghostly fingers twitched the moose-hide walls. The medicine lodge shook, the poles bent from side to side. Obviously, spirits had descended. For a tied, helpless man could not make strong walls tremble. The council fire died. Embers glowed. But the cries of bird and beast still sounded; the howling of great winds, the snapping of ghostly fingers, the steady rasp of the tortoise-shell rattle came from the tent, shaking now as in great winds. As the embers lost their light, tiny flecks of green fire appeared around the tent. All knew that the shades of dead warriors would give wisdom to their people. Now they announced their presence; each spoke his name. A chief whose deeds were tribal legend counseled war in a full-throated voice. (Who could think this was the voice of the conjuror?) The ghost chief hinted of danger. The tent's shaking made more awesome his words. Then the spirits were gone; the strong saplings no longer shook. The elders found the conjuror as firmly bound as ever.

In a lecture hall, ladies settled the enormous skirts decreed by fashion in the 1860's. There would be a demonstration now at which they could only wonder. An old gentleman walked to the center of the platform and paused for quiet. With the silvery voice of a popular preacher but with an underlying note of complete sincerity, he told the strange history of the two young men now to appear, of their seeming power to call spirits from the vast deep, of the motion incredibly imparted to objects placed near them—even though the lads would be firmly tied by volunteers from the audience. To a round of applause, broken by a few boos and hisses from skeptics, he introduced the wondrous brothers, Ira Erastus and William Henry Davenport. The dapper, handsome youths took their places. Their hair was fashionably long, their sweeping mustaches and “imperial” beards neatly trimmed. Behind them rose their famous cabinet. It was no deeper from front to back than a narrow chair, no taller than a standing man. There were three doors. The center door had a tiny, curtained window. A committee from the audience filed hesitantly onstage, a bit dazzled by the footlights, lamps in front of bright tin reflectors. The lecturer produced two short pieces of rope and a single long coil. Volunteers agreed to do the tying “so that the young men cannot possibly be accused of producing the phenomena themselves.”

Ira Davenport extended his left arm; the rope was tied around the wrist with a good square knot over the pulse. The dashing young man with the dark curls and mysterious black, flashing eyes placed his left hand behind his back, then his right. He turned and the audience could see that he held his right wrist against his left. The committeeman settled one wrist firmly against the other, brought the ends of the rope around the right wrist and tied them fast, inspected the knots and tugged at the arms. The youth could not possibly use his hands. With brother William Henry similarly secured, the boys took their places inside the cabinet, one at either end, where they sat on shelves facing each other. The committee knotted the long rope about the knees and ankles of one; then stretched it to tie the other's legs in the same manner. A guitar, a tambourine, a horn, and a bell were placed in the center of the cabinet as the doors were closed. Hardly had the catch of the door snapped when tambourine and bell flew through the center window. At once the master of ceremonies threw open the end doors. Both boys were firmly tied.

In 1914 a forty-year-old man—an athlete, a veteran of vaudeville and before that of the circus, the carnival midway, the dime museum, the medicine show, and the beer halls—began the last mystery of his now famous act.

He was well under average height, powerful without being bulky, bushy-haired, and a little bowlegged. His face was sharp-featured yet handsome, with intense blue-gray eyes. His strong, agile fingers had—in the first minutes of the show—unfastened the buckles of a straitjacket through heavy canvas. Then, in an exhibition of straight magic, he had cut into a length of cloth and magically restored it. This had been followed by his famous needle trick. He apparently swallowed three packs of darning needles and thirty feet of white cotton thread, then produced the end of the thread from his lips—with a needle dangling from it! After handing the tip of the thread to an assistant, he backed across the stage. Little glittering steel points, each threaded on the cotton, emerged from his mouth. The needles had been threaded! Now he announced that the evening's last mystery would be his own invention, the exciting and celebrated Chinese Water Torture Cell. The curtains revealed, ominous beneath a single spotlight in the center of the stage, a mahogany cabinet. A glass panel glittered in its front. An excited audience watched, entranced, as assistants filled the cabinet with water from a firehose.

The man of mystery, offstage for a moment, entered in a dressing gown. Removing the gown, wearing only the bathing suit it covered, he lay down while an assistant imprisoned his feet in a mahogany square with two openings, not unlike the stocks of the seventeenth century. The “stocks” were fastened to a rope descending from the flies. The man was raised, then lowered head down into the water. Liveried attendants locked the top of the tank in place. A cabinet with metal-pipe frame, curtained with dark blue velvet, was lifted forward to enclose torture cell and the occupant, until now plainly visible upside-down in the water. When the curtains closed, an assistant with a fire ax stood by. For two and a half agonizing minutes the audience saw imminent tragedy in the ax poised to smash the water prison. The ax never fell. The curtains parted and the magician stepped out, streaming water. Behind him stood the grim cell, its cover still locked and clasped.

When the applause finally began to dwindle, the man who had escaped raised his hand: “Ladies and gentlemen,” he spoke, in a rather high-pitched voice that somehow (he did not shout) carried to the top row of the balcony, “allow me to thank you for your generous applause. And to make the first public announcement of my most recent development in the field of mystery. On Monday, the sixth of July, when I open at Mr. William Hammerstein's Victoria Theater in New York City, I shall present a feat which has, since the dawn of history, been considered an absolute impossibility. I shall endeavor to walk through a solid brick wall.”

Harry Houdini did just that. Or seemed to. The wall was of solid brick, built on a foot-wide steel beam by a squad of bricklayers before the eyes of the audience. Over a large carpet in the center of the stage was spread a seamless sheet of cloth. Members of a committee from the audience stood on its edges. Screens were placed on each side of the wall and the magician stepped behind one. They heard his voice from the screen, “I’m going ... I'm going ... I'm gone!” Then quietly—from the other side—“Here I am!” He stepped out to greet an audience at first stunned into silence. There was, everyone could see, no connection possible by a tunnel under the wall. The carpet and canvas made that impossible. There was no way around the wall. The committee could see both ends. Everyone could see that he did not go over the barrier. . . . Then how? How did a man walk through a wall?

In previous appearances, he had released himself from ropes and handcuffs, from sealed sacks and bound trunks, from packing cases nailed fast, from stocks and pillories, from coffins, from iron boilers riveted shut, from a giant milk can filled with water, its lid secured with padlocks. But, until now, the Escape King had always left the wondering spectators at least a loophole for speculation. “He opens the handcuffs with magnets.” “The box is made to fall apart when it gets in the water.” “People come up out of the stage by trap doors and let him out of the torture cell.” All wrong, but something at least for the mind to envision. Now there was nothing. Speculation was simply torment. Houdini had done the utterly impossible. Where would he go from here? Where? The following year he entered a box and was buried deep in the ground. In twenty minutes, he reappeared. He had escaped from the box; he had dug his way back to the air and light, to freedom. All escapes were possible for the man who walked through walls.

When he was dead, myth made even more elaborate the legend built during his lifetime: that he had a Secret and he had carried this Secret to the grave. This legend died in the public mind only when Houdini again held the headlines. He had come back from the grave; the voice of a spirit medium had given a ten-word code message to his wife. It did not matter that Bess Houdini denied that it was a spirit message known only to herself. The legend grew. It is still talked about, as Houdini is still remembered.

Time, Lord Dunsany tells us, eventually will conquer even the gods. This book is an effort by one who remembers Houdini in the days of his glory to preserve the fascination of the legend, and at the same time to show a little of the man himself: stormy, and devoted; cruel, and warmhearted; unselfish, and egocentric, he is no easy subject. He was ruled by emotions. His natural shrewdness often was lost in impulse. He was one of the most annoying, most likable, most unpredictable geniuses that ever lived. Can what he was, what he did, have any meaning for us? The author wrote with that conviction. Harry Houdini began with nothing—nothing, that is, but courage and a belief in his own genius which amounted to obsession. As the archetype of the hero who could not be fettered or confined, he became the idol of a million boys, a friend of presidents, and the entertainer of monarchs. This was the Houdini who stepped out of the wings as a legend in his own lifetime. What of the man hidden by the legend? For all his crotchets, Houdini had one great source of power. Courage was that power, and he knew that courage must be practiced as diligently as sleight-of-hand. He was no master manipulator of cards and coins, in spite of his ambition to be remembered as a wizard of dexterity. But he did manipulate life and circumstance and the imaginations of men. By reviewing his life, let us see how he went about it.

1 - Discovery by Gaslight

The early dark of an autumn evening had fallen over Manhattan and now at the street corners night was dispelled by the glow of gaslights on their posts—a soft radiance soon to give way to the electric glitter of progress. Under the corner lamp the boy paused and opened his book. It was a battered specimen rescued from the ten-cent stall of a bookshop. The lad had counted out his pennies and found he could spare ten. He had to keep a nickel for his fare on the Third Avenue Elevated. In one hip pocket he carried a dog-eared deck of playing cards. Ordinarily, on his way home from his place of employment, the necktie factory of H. Richter's Sons at 502 Broadway, he would practice a sleight known as sauter le coup, or “jump the stroke.” But now he had found something infinitely more fascinating; a world of marvels to which the mastery of magic might admit him. And he had found himself! All the restless yearnings of youth for fame and wealth, travel and the friendship of the great were in this book; its author had known them too. The book was The Memoirs of Robert-Houdin, Ambassador, Author and Conjuror, Written by Himself. If a young notary's clerk, Jean Eugène Robert, could rise by patient efforts and stout heart to be the “father of modern magic,” then he, Ehrich Weiss, necktie-lining cutter, could do the same.

From that moment, as the events of his life make clear, Ehrich Weiss never doubted his destiny. Crushing defeats, snubs, family pleading for other ambitions did not stop him. Although tireless practice never gave him the polished ease of the star sleight-of-hand performer, he hacked and carved his place on the heights by inventing a whole new form of magic. He hurled at the universe a challenge to bind, fetter, or confine him so that he, in turn, could break free. He triumphed over manacles and prison cells, the wet-sheet packs of insane asylums, webs of fishnet, iron boxes bolted shut—anything and everything human ingenuity could provide in an attempt to hold him prisoner. His skill and daring finally fused deeply with the unconscious wish of Everyman: to escape from chains and leg irons, gibbets and coffins . . . by magic.

The Weiss family had come to the new world from Budapest, Hungary. Ehrich, the son of a rabbi, was born in the ghetto section of Pest shortly before the family came to America. In the excitement of the trip, the exact date of his birth was apparently forgotten. The Weiss family settled first in Appleton, Wisconsin. Since his mother always wrote him on April 6, Ehrich claimed that date as his birthday and Appleton as the place. Just before the invasion by the Nazis in the Second World War, a Hungarian magic enthusiast, Dr. Vilnos Lenard, found in some synagogue records an entry describing the birth of a son, Ehrich, to Mayer Samuel Weiss on March 24, 1874. The records survived pillage, and examination of Dr. Lenard's discovery may finally settle the matter. The actual date and place of Ehrich's birth are not truly important. It is important that he took great pride in being an American. The Weiss family was numerous. Ehrich was a fifth son. The first-born boy died in Hungary, the second-born in New York shortly after the family came from Wisconsin to settle there in 1888. Two living brothers were older than Ehrich; two were younger, as was his only sister. In their home on East 69th Street, the six Weiss children came quickly to know their parents' pride in family. They lived in an atmosphere of dignity and respect for learning, an atmosphere that contrasted sharply with the world in which Ehrich's destiny lay. If the fact that he never ceased to return to it is evidence, Ehrich loved his home.

He knew the record of his early life was obscure. Later, when he had fallen out of love with his first hero, he wrote of Robert Houdin: “Because of his supreme egotism, his obvious desire to make his autobiography picturesque and interesting rather than historically correct . . . it is extremely hard to present logical and consistent statements regarding his life.” The statement is equally true of Ehrich Weiss.

There is a romantic legend, built up from publicity material and souvenir-program biographies, which tells us that the performer called Houdini was an amazing infant who never cried and needed little sleep, who as a very young child showed so impressive a mastery of locks that a professional locksmith employed him. The legend adds that at the age of nine Houdini was discovered by Jack Hoeffler's Five Cent Circus when it played Appleton and was engaged to do an act he had originated—picking up pins with his eyelids while hanging head down from a trapeze! The stories are apocryphal. It is probable that Ehrich Weiss was introduced to magic at the age of sixteen. His first teacher was Jack Hayman, who worked next to him in the necktie factory. This was the job to which Ehrich had gone after his father gently remonstrated with him about his being a newsboy. A man of impressive dignity, Dr. Weiss explained that selling papers in the street was no occupation for the son of a rabbi and scholar.

In his spare hours, Ehrich was a loyal member of the Pastime Athletic Club. He trained for and won some track events. He also gained skill as a swimmer, doing most of his practice in the garbage-laden waters of the East River, where he joined the other neighborhood boys. Ehrich's interest in spiritualism was aroused when, with Joe Rinn, a friend from the Pastime A. C., he visited the home of the notorious spirit medium, Minnie Williams. Mrs. Williams' house on 46th Street had been acquired from an ardent believer who was advised by the spirits to sell for one dollar and no other considerations. As Mr. Rinn tells the story, when the young Ehrich Weiss entered this plush palace of ghostly mystery he nudged Joe and whispered, “There must be plenty of money in this game.” No wonder he thought so. This was probably the most ornate house he had ever seen. Certainly, it was different from the crowded flat of the scholar and gentleman, Rabbi Weiss. Ehrich sat beside his friend Joe while hymns were sung. The room was lighted only by the dim greenish glow of a lamp in a box. In time, spirit forms came from the curtained corner of the room which was called the “cabinet.” Among the shades resurrected that evening was Dr. Henry Ward Beecher. The boys noted that the floor creaked in very unghostly fashion when the spirits walked across it.

As he left, Ehrich accurately estimated that Mrs. Williams had taken in forty dollars: forty people at a dollar a head. Even after paying two thugs who were her bodyguards, she had, he reckoned, a good net profit. Ehrich knew his factory labor could never give him the money taken in here. But, although he already had a deep interest in illusion, he was not then tempted to become a medium. There were other reasons than conscience and lack of experience. For one thing, his father wouldn't have permitted it. If being a newsboy was no job for a rabbi's son, being a spirit medium would have been infinitely worse.

Soon, Ehrich's hours of dedicated practice began to reward him. Every now and then he was able to appear in public as a prestidigitator. On even rarer occasions he was paid a dollar or two. This was a time-honored and practical course. The amateur gained the experience before live audiences that made possible a chance for professional appearances. For Ehrich, as for all newcomers then, professional life began in beer halls and cheap vaudeville theaters. He worked hard as an amateur to gain such stages.

In these early shows young Weiss was grandiosely billed as “Eric the Great.” Frequently his assistant was his pal from the factory, Jack Hayman, who had not only shown Ehrich his first simple tricks but had taken him down to the Bowery where professional apparatus was glitteringly displayed behind the glass counters of magic shops. Such equipment was far beyond their means. Cards, however, were cheap, as were silk remnants. So Ehrich's act at first consisted mainly of effects with cards and silk handkerchiefs, though he also used a few magic boxes and other props that he had built himself.

Jack Hayman had introduced Ehrich to magic. Now he indirectly helped him to choose the name he made immortal. Jack told him that adding an “i" to a word in French makes it mean “like.” Ehrich never questioned this. An “i" added to the name of his hero, Houdin, produced Houdini. (It was many years before Ehrich realized that the hyphenated Robert-Houdin meant that Robert was not his idol's Christian name.) And since a performer customarily has a given name, and since Harry Kellar was then the biggest “name” in magic, Ehrich Weiss became Harry Houdini. Perhaps the choice had been inevitable since the moment he opened Robert-Houdin's memoirs.

2 - The Book of Revelations

Now the boy who was Ehrich Weiss by day and Harry Houdini by night found direction and challenge in another book. The second half of the nineteenth century was the great age of applied occultism. For forty years a movement called spiritualism had been growing in the face of skeptical scorn. It had begun in a farmhouse near Hydesville, New York, where in 1848 two little girls, Katie and Margaret Fox, began to tease their superstitious mother by tying an apple on a string and bumping it over the floor at night. Later the sisters learned to make rappings by snapping the big toe against the second toe. Under the management of their older sister, Leah, a hard driving and money-hungry termagant, the girls toured the country giving séances at which rappings answered questions. Soon a sickly Scotch-American lad in Connecticut, Daniel Dunglas Home, began to produce rappings himself. And even before Home achieved fame and diamond cufflinks for his endeavors, the Brothers Davenport had hit the lecture circuit with their cabinet in which ghosts romped.

At last, in 1891, a bombshell was heaved into the world of luminous nightshirts and self-playing accordions. It came in the form of a paperbacked book entitled Revelations of a Spirit Medium, or Spiritualistic Mysteries Exposed/ A Detailed Explanation of the Methods Used by Fraudulent Mediums/ by A. Medium. The price was one dollar. The book was copyrighted under the name of Charles F. Pidgeon. Serious students of psychic research and its literature have since ascribed authorship to one Mansfield, to one Donovan—the list of possible authors is long. Whoever the author was, he probably had been a professional “physical phenomena” medium—a producer of voices, spectral forms, raps, etc. At very least he had closely consulted one.

Angered mediums, so the story goes, began buying up copies and shoveling them into convenient furnaces. Sadly, their patronage couldn't save the publishers. They went out of business and the book soon became a rare volume. One copy somehow came to the hands of the newly named Harry Houdini. At that moment he was disinterested (he would not always be) either in spiritualism or in charges of fraud against some spiritualists. He was, however, interested in how the fraud was managed. This slur on spiritualism made a superb text for an escape artist. There were, as an example, explanations in minute detail of the way a medium—or Houdini—might get out of ropes with which he had been tied. (The medium called this trussing a “control.”)

More, the text set out with illustrations the secret of a spirit collar, an iron band to be secured about a medium's neck with a padlock. Of course, the collar never accomplished the announced purpose of holding a medium to a wall, since it could easily be opened by means of a cleverly-devised hinge. There were also explicit directions, and more pictures, about making “spirit” bolts, devices used to fasten a medium to a solid support. Harry learned how this ring-and-bolt contrivance opened to free the wearer. He also found directions for two very mystifying ways to escape from a sack when its drawstrings had been pulled tight, knotted, and sealed.

His preoccupation with escape was instant and intense. Moreover, it endured. Harry became an ardent, tireless student. As often as he could persuade them, he got his Pastime Athletic Club friends, who were doubtlessly puzzled, to tie him up. It was with this concentration of effort that, eventually, he achieved a mastery of the art that has never been surpassed. On one occasion he saw the great Harry Kellar, in his full evening magic show, use the famous Davenport wrist-tie for comic effects, shooting out one free hand to tap the volunteer from the audience, after the volunteer was sure that he had tied the magician so securely that he was helpless. The trick itself delighted the youthful Houdini. He was particularly excited though, by Kellar's challenge: “I challenge you to tie my wrists together with this rope so that I cannot release myself!” He loved that, and it was always to be so. The whole pattern of his career indicates how profoundly he must have been moved by the gesture Kellar handled so commandingly. But years separated Harry Houdini from realization of the full dramatic power of the challenge and full understanding of its most effective presentation. The story will grow with Houdini's growth. For he made the challenge a device peculiarly his. Year after year he defied the world to confine him—and year after year, or so he boasted, he never failed to escape.

At seventeen Harry made the great decision. He entered show business as a full-time professional. In April 1891, he quit his job at H. Richter's Sons, taking with him a good recommendation from the boss and the prospect of trouble at home. It must have been impossible for his parents to appreciate this exchange of a decent job with assured income for the dubious standing and chance employment of an apprentice wonderworker. For Harry there could have been no other decision.

Somehow during that spring he talked his way into a tryout at Huber's Museum on 14th Street, next door to the present site of Luchow's Restaurant. Presiding over the establishment was George Dexter, a tall, suave gentleman from Australia. Dexter, an eloquent “inside talker,” introduced the acts, most of which were at the circus sideshow level. Dexter was a man of the world, experienced in all kinds of variety entertainment, and, most important for Houdini, a master of rope escapes.

The rope-tie effects have been a favorite of traveling mountebanks as long as there have been fairs and festivals, circuses and amusement-seeking crowds. In fact, this form of escape antedates organized entertainment. Ojibwa sorcerers seemingly accomplished mysteries of tribal ritual after being bound. The trick probably was old when it came to the Ojibwa and must have begun its evolution deep in man's prehistory. It seems appropriate that the great escapist should have started to learn the art at, quite literally, its beginning. Dexter was delighted to find that the young card-manipulator was fascinated by “escapery.” Immediately he coached him in the essentials of the rope-tie artistry. He taught him, also, handcuff manipulation. Somewhere along the line some enterprising carnival performer had found that the sight of a man with handcuffs on his wrists has a strong fascination for a midway crowd. Again it is the element of challenge—can he get out? And if so, how?

As presented, even to this day, on the “bally” platform of a carnival ten-in-one show, the handcuff escape has the simplicity of all good magic and, like all good magic, depends for its effect on the acting ability of the performer. Here is a presentation typical of the ones Houdini must have watched: The crowd, idly sauntering along the shavings-cushioned earth of the midway, confused by a plethora of attractions, suddenly has its attention called by noise from the bally platform of a sideshow. A girl, clad in a costume as brief as the law allows, is being handcuffed by a large, official-looking man. The scene is arresting in itself. Here is beauty in distress! The outside talker brings the crowd close. There is business back and forth between the officer and the talker on the platform. More business, back and forth, while the girl stands between them, the gyves on her wrists.

There is something archetypal and deeply stirring in the male human at the sight of a pretty girl in manacles or chains. While the audience stares entranced, the talker throws a cloth over the girl's hands. The crowd, or “tip,” begins to sense that it is all a part of the show, but stays nevertheless. The girl, writhing as if in pain, struggles for a moment and then the handcuffs fall to the floor of the bally platform with a clang. The cloth is waved above her head and she dashes inside the tent followed by a portion of the tip—for no good reason that they could explain except that they want to see where she goes and what she is going to do when she gets there.

The official-looking person is any beefy individual who happens to be connected with the show or the carnival or, on occasion, a real detective who is persona grata with the showman. What the girl has done is to find the keyhole in the cuffs with a key, under cover of the cloth, and release herself, writhing the while as if she is squeezing her hands smaller than her wrists to slip the cuffs off. That, in essence, is the “handcuff trick”—as old, probably, as the invention of handcuffs.

Houdini's genius did not lie in invention of new effects from scratch; rather he was a developer of unsuspected potentials of drama in old effects. The uninspired midway performer, getting out of the cuffs with a duplicate key, seldom really plays it for drama. And for a long time, Houdini, after he had acquired a pair of cuffs from some pawnshop, fell into the trap of showing his cleverness by making it all look easy. The drama lay, and he did not learn this for a heartbreakingly long time, in making the feat seem hard.

He was similarly tardy in seeing how he might put to use a special bit of information, a “secret” about handcuffs that is known to few except peace officers: Nearly all cuffs of the same make and model (before 1920) opened with the same key. Most people believe a key is unique. If they buy a half dozen padlocks, they expect to have six different keys. But the locks of handcuffs are more simple, as simple as the locks of briefcases. Local police may place five pairs of “regulation” cuffs on the escapist's wrists. If all are of the same make and model, one key often frees him. Houdini early learned this about manacles, but he was slow to exploit what he knew. When he finally did, he used it with great imagination. With his own keys for all the makes of cuffs in current use in any city, he could safely challenge police officers to manacle him. In every city he could then extend his reputation as a magician who could free himself “by magic.”

After his spring engagement at Huber's Harry decided to try his luck at Coney Island. He worked briefly with Emil Jarrow, a strongman who could write his name on a wall with a pencil while holding in the same hand, straight out from the shoulder, a sixty-pound dumbbell.

Jarrow and Houdini worked for “throw money”—that is, they put on their show in a tent and then passed the hat. Jarrow, after getting a page write-up in the New York Sun, went on to other activities and, with the irony of fate, he became one of the most adroit sleight-of-hand performers in the business at his own specialty (the trick where a borrowed and marked dollar bill vanishes and appears in the center of a lemon which, up until the moment of slicing, has been in the hands of a spectator)—whereas Houdini, the sleightster, grew to be something of a strongman.

It would be impossible to follow Harry from obscure booking to obscure booking. He went everywhere. In December 1891, he sent a letter to Joe Rinn from Columbus, Kansas, saying that he was with a show in the ten-, fifteen-, and twenty five-cent bracket, and that he was doing his own bill-posting. It's more likely that he was passing out handbills telling of his prowess, an inexpensive form of advertising he used all his life. After Dr. Weiss died in 1892, the support of their mother and sister was up to Houdini and his brothers. Harry thus had one more motive for playing as many weeks as possible. He assured his mother that one day he would pour a stream of gold pieces into her lap. Mother Weiss had her doubts. When Harry came home, it was not to rest. Day after day he practiced rope-tie escapes on the roof of the East 69th Street house. His kid brother, Theodore, who earned the nickname “Dash” for his love of bold haberdashery, would enthusiastically spend hours tying Harry. Harry would spend more strenuous hours wriggling out. What the boys did mystified their mother. Never in all the history of the Weiss family, which had produced a number of rabbis and Talmud scholars, nor in the annals of her own family, the Steiners, had anyone senselessly allowed himself to be tied up with clothesline. “Nu, so from this you should make a living, my son?” “Never mind, Ma, I got an idea.”

Ehrich had a secret. For the first time in his life he had borrowed money—enough to purchase a box trick from a broken-down magician. This box, which was the size of a small trunk, had a secret panel that opened inward. With a man inside, the box could be locked, then roped from side to side and from front to back. With a curtain drawn to conceal the method of escape, the imprisoned man would be outside in a few seconds, the locks and ropes undisturbed. The trick was originally the invention of the English illusionist John Nevil Maskelyne. With many modern improvements it is still being performed wherever magicians can find a stage. Worked by two people who are exceedingly agile, it becomes a genuine miracle.

Houdini was agile, and his kid brother Dash was willing. With Harry's box the Houdini brothers had an act. Both believed in giving audiences plenty of show for their money. Many observers thought it was too much. But Houdini was on his way!

3 - The Brothers Houdini

In 1893 the Midwest erupted with a skyrocket burst of outdoor show business. Nothing like the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition had been seen before in the Americas. The fair had been planned to commemorate the four-hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America, and was scheduled for 1892. But nobody minded the year's delay; it gave an extra twelve months for buildup in the papers. Of all its attractions, the Midway Plaisance (which gave the English language a new word: midway) was a street of wonders—it featured an Eskimo village, a South Seas village, and “The Streets of Cairo,” where Little Egypt gave the West its first view of the belly dance. Every outdoor act in the country seems to have headed for Chicago during that memorable season, and so did Harry Houdini with his new partner, Dash. The boys, billed as the Houdini Brothers, took their trick box with them. In later years they remembered working in one of the sideshows or a ten-in-one on the giant midway. They may have done so. The Fair seemed big enough for everybody. Even Minnie Williams was there with her bodyguard-manager, Bug MacDonald.

In the nineteenth century's biggest of big shows, an apprentice magician and his novice partner did not set Lake Michigan on fire. Of their fortunes, misfortunes, successes, and failures at the fair there is no trace. But there is evidence that Harry—without Dash—was booked by Kohl & Middleton's Dime Museum to do a single for twelve dollars a week. Here was the place to get intensive experience. He gave twenty shows a day! Between shows he spent the little time he had observing the other acts. And a fascinating crew they were.

Many had been engaged because of some deformity or natural anomaly—the midgets, the alligator-skinned boy, the bird girl. Others produced gasps with stunts that mystified or startled crowds, and these captured Houdini's professional interest. The sword swallowers, he discovered, actually let the solid steel blades slide down their throats; they had conquered the gag reflex. He learned that fire-eaters may put in their mouths awesomely blazing materials, so long as they never forget to breathe out gently to keep the heat away from the soft tissues of the roof of the mouth. Houdini admired these acts. His bête noire of the Dime Museum, however, was Horace Goldin, whose rapid-fire illusion show was already winning fame. Goldin appeared in the annex of the museum. This, in itself, was a mark of achievement, since admission here was a dime extra.

When Houdini approached Goldin on a one-master-of-mystery-to-another basis, Goldin told him loftily: “Look here, kid—you're getting twelve a week. I'm getting seventy-five. That makes me six times as important around here as you.” Houdini boiled. It was twenty-five years before he forgave Goldin. In the end they did become good friends, as great figures of vaudeville's golden age.

Once back in New York, Harry's spirits, crushed during the day by constant grinding attempts to book his act, were revived at night by the tender scolding and fussing of Mother Weiss. For the Brothers Houdini, reunited and playing around New York, times were so difficult that to anybody but Harry they would have been considered impossible. But Harry never succumbed to the lure of a prosaic job and regular folding money every week. He always knew what he wanted, and his determination to get it was extreme. Harry had started his career with a number of formidable handicaps. Most people who paid for entertainment expected a magician to be a tall and impressive man, either slender, dark and Mephistophelean (Hermann was the model) or big and stately (Kellar set the style). Houdini was neither. He was short—only about five inches over five feet—and, like many other men who lack height, he wore his hair long and bushy. His clothes, in youth as in middle age, always looked as though he had slept in them. His speech connected one grammatical error with another so that even booking agents not celebrated for sensitive ears immediately graded Harry as small time. He had also to remedy shortcomings more immediately harmful. Although he had done magic before demanding and potentially abusive audiences, he was still young; he worked too eagerly and too hard. He had no flashy apparatus. He did not do sleight-of-hand magic well. He was too proud to haggle over the price of his services, and this was only one of his faults as a businessman. He was healthy, intelligent, and determined. To the casual observer these might have seemed his only assets. No, there was one more. His face was handsome—in moments of concentration its burning intensity could grip the attention of the audience. Then he would smile and the gray-blue eyes, smoldering a moment before, would dance. He could smile a winning, enchanting smile that could make any crowd forgive a bungled trick. That wholehearted, boyish smile stayed with him all his life. It served him well in innumerable tight spots. He needed the defense of a smile in the beer halls he played.

There are rowdy night clubs today where the customers gab during the efforts of entertainers, but the basic toughness of these spots lies in the relationship of the patrons to one another, rather than any concerted attempt to heckle the talent. The beer hall of the nineties has no real descendant. The tables were small and the aisles between them were just barely wide enough to let a waiter wedge his way through. Fights were frequent. The show went grimly on while waiters moved the combatants to the sidewalk.

The performers were weary at times, although there were “regulars” among the talent who seemed never to tire and gave out with such volume of song that they drowned out the gabble of drunken conversation. The stage was usually a narrow platform with draw curtains. Sometimes it was without even this refinement. The girls of the “line,” when there was a chorus, tended toward beef, as the taste of the times required. A novelty act had to fight extra hard to get a hearing. In such a “palace of amusement”—decorated with artificial autumn leaves tacked to the ceiling beams, foggy with smoke and acrid with stale beer—young Harry Houdini would step out “to show youse a few experiments in de art of sleight o' hand.” There was never any lack of volunteers to tie him up. The beer halls were well patronized by sailors.

At the blaring playground by the sea, Coney Island, was a street of cabarets called The Bowery, famous now for the start it gave to ambitious youngsters. Down the years Eddie Cantor, Irving Berlin, Jimmy Durante and Vincent Lopez all played here.

The Houdini Brothers came now to Coney's Bowery cabarets and cheap “vaude” houses. Harry had taken a step up from his tent show here with Jarrow. With Dash, he was in a theater performing the box trick. They played it well. One was tied with a strip of braid around his wrists and locked in the box. The curtains closed. The other partner, putting his head through the curtains, counted, “One, two...” His head ducked out of sight. “Three.” This time the other boy's head appeared. The curtains parted. The box was unlocked and inside, tied with the braid, was the Houdini who originally had been outside!

These were the last days of the Houdini Brothers as an act. Soon the billing became simply The Houdinis. For a girl had entered the picture—a tiny girl who weighed less than a hundred pounds and was just breaking into show business herself. Her stage name was Bessie Raymond. In later years Dash always claimed that he saw her first. But it was Harry she fell in love with and married.