11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

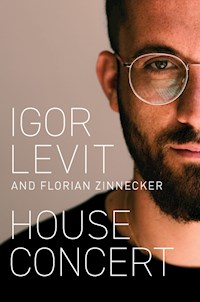

Igor Levit ranks among the greatest pianists of his generation, described by The New York Times as ‘one of the essential artists of our time’. But his influence reaches far beyond music: he uses his public platform to speak out against racism, antisemitism and all forms of intolerance and prejudice. Convinced of the duty of the musician to remain an engaged citizen, he is recognized and admired for his willingness to take a stand on some of the great issues of our day, even though it has come at considerable personal cost.

When the pandemic broke out and Levit was unable to give live concerts, he switched his piano recitals from concert halls to his living room and gained a huge international following. This book opens a window onto Levit’s life during the 2019–2020 concert season, charting the transition from his whirlwind life of back-to-back live concerts in packed concert halls to the eerie stillness of lockdown and the innovative series of house concerts livestreamed over Twitter. A year in which Levit spoke out against hate and received death threats in response. A year in which he found his voice and found himself – as an artist and as a person.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 343

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledegments

Epigraph

House Concert

Notes

Afterword

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

House Concert

IGOR LEVIT

FLORIAN ZINNECKER

Translated by Shaun Whiteside

polity

Copyright Page

Originally published in German as Hauskonzert © 2021 Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, München

This English edition © 2023, Polity Press

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5355-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022935473

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Dedication

to our families

and

our friends

Acknowledgements

Work on this book ran like a constant through a time of turbulence, some of which was at first unforeseeable. For that reason alone, the writing of the book itself was never without its challenges: there was hardly an event that didn’t have to be repeatedly postponed, hardly a plan that didn’t have to be scrapped and redrafted. If it hadn’t been for the unshakeable conviction of a lot of people that it was a good idea to write this book right now, and if those people had not in their own way accompanied and encouraged the process of its making with trust, generosity, expert understanding and patience, both making it possible and helping to carry it along: we would never have made it.

These include first and foremost Maren Borchers-Fromageot, Henriette Gallus and Kristin Schuster, Simone Bode, Anselm Cybinski and Andreas Neubronner, Felix Broede, Georg Diez, Boris Fromageot, Philipp Nedel and Thorsten Schmidt, Moritz Müller-Wirth, Kilian Trorier, Marc Widmann and Bettina Tschaikowski, Kai-Uwe Diaz Philipp and Martina von Brüning, Stefan Arndt, Christian Möller, Andreas Morell and Carolin Pirich, Ulla Kalchmayr, Justus Wille and Charlotte Hartwig, with particular thanks to Jo Lendle, the editorial team and the rest of the crew at Hanser Verlag, Hanna Hesse, Christina Knecht and Kirsten Vogelsang, and most especially to Margie Oberle and Kasimir Straubert, Stephanie Bartsch and the late Ralf Oberle. Antonia Goldhammer, Christiane Lutz, Elena and Simon Levit, Karin and Peter Zinnecker, and very specially to Nora Zinnecker.

Warmest thanks to you all!

Igor Levit and Florian Zinnecker

Epigraph

If you understood everything I said, you’d be me.

Miles Davis

House Concert

Berlin, a Saturday in December 2019. Igor Levit is tired, his right arm hurts; it mightn’t be the best day to get started.

Two days ago he got back from a short tour with the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen. Hamburg, Wiesbaden, Vienna, Bremen, seven performances in eight days. The Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 four times, No. 2 three times. In the weeks before that he played for four evenings each the first half of his Beethoven sonata cycle in Hamburg and Lucerne, on two evenings four sonatas, on two five. And in between there was his inaugural concert as piano professor at the University of Music, Theatre and Media in Hanover. On the programme: a movement from a symphony by Gustav Mahler, after that a passacaglia by Ronald Stevenson, lasting an hour and a half. Enough repertoire for a whole year. Or for three pianists.

Perhaps it would be better to start a few days earlier; it would be easy to make him look good. Then Igor Levit would be sitting at the grand piano right now, pounding the conclusion of the first Brahms concerto into the keys, stormy, ardent, bursting with energy, and then: applause, cries of ‘bravo’, ovations.

That’s how books about pianists begin.

And not on a gloomy Saturday morning in a packed café in Berlin-Mitte, where the only available seat is the one by the door.

But there’s nothing to be done.

Levit is late, even though his apartment is only a few blocks away. He walks jacketless through the icy rain. Neither his manager nor his press agent know about this date, despite the fact that there is hardly anything in Igor Levit’s life that they haven’t authorized.

But he isn’t here for professional reasons. He has some time off – two weeks – his first free days since September, and the next concert is on Boxing Day. ‘It’s possible that in those two weeks I’ll work out that I need another twelve.’

He takes off his glasses and runs his hands over his face.

How was the tour with the guys from Bremen?

‘Ok.’

He runs his hands over his face again.

‘You know, piano concertos take it out of you. Much more than solo recitals. I love doing solo recitals. Then I have two hours on stage, and those two hours belong to me. I might mess it up. But it’s still mine. With a piano concerto I’ve got maybe forty minutes, maybe even only twenty. I sit there and there’s nothing I can do, I’m completely dependent on the energy of the orchestra. If the orchestra’s right, it’s good, and if not, it gets difficult. I know from the very first bars.’

He kneads his right shoulder and pulls a face.

What’s up with your arm?

‘It’s ok.’

Right now, his left arm almost hurts more than his right; last night Igor knocked the funny bone in his left elbow, by accident and quite violently. His right arm has already been sore for a few days: too much Brahms, too much Beethoven, too much everything.

‘If I had to go up on stage later on, no problem. But this morning I could barely brush my teeth.’

We’d actually met up to talk about something else.

More precisely: about one question in particular.

Levit is one of the best pianists of his generation, some say the best of the century, which is quite an unsophisticated judgement, and not one that he himself likes to hear. One music critic applied the superlative, but he’s not keen on such descriptions. His press agent has the term ‘pianist of the century’ deleted from all his interviews.

Recently almost all the big newspapers discussed his complete recording of the Beethoven piano sonatas. A few weeks ago a there was a big profile about him in Die Zeit and now Alex Ross, the music critic of the New Yorker, is coming to do another big profile, and Stern’s working on a piece as well. Bayerischer Rundfunk is planning a Beethoven podcast with him, thirty-two episodes, one for every piano sonata. In September he was on the stage of the Thalia Theater in Hamburg talking to Wolfgang Schäuble about the German constitution, and recently he was a guest on Maybrit Illner’s political talk show on the ZDF channel to discuss hate speech. Igor might well be among the best pianists of the century – he’s certainly the most visible. And then there’s his Twitter account.

All that’s really missing is a book.

Haha.

But seriously.

Almost all the articles, interviews and podcasts are either about Igor Levit, the pianist who expresses political opinions. Or Igor Levit, the Twitter activist who also plays the piano. Mightn’t it be time to talk about how the two things come together, how it began and where it’s going, in short: why Igor Levit sounds the way he does?

Levit says nothing.

Kneads his shoulder.

Looks out of the window into the gloomy morning.

‘Quite honestly? No idea. No idea how long I’ll keep on doing it. How long I want to carry on.’

How long he wants to carry on what?

‘It could be that it’s because I’m exhausted. But right now, I really don’t know.’

He kneads his shoulder again.

‘It’s not enough for me. I’m constantly travelling, I play concert after concert after concert, but once the concerts are over, I don’t sit down, pat myself on the back and say: Goooood concert! Goooood concert! Instead, I immediately ask: What’s next? I’m travelling about at the speed of light, because I’m always worried I won’t have time.’

He rests his head against the wall and shuts his eyes. But only for a moment.

‘You know, right now there’s not that much at stake. What can happen? I can play the Waldstein Sonata in G major rather than C major, and at half-speed – who’s going to stop me? Or the Moonlight Sonata two octaves higher and really fast. So? If I do that they can say I’m a dick. So? I can play badly at a concert, I can get lost, forget how it goes. What happens then? I might get booed, I might get a lousy review and the organizer won’t have me back. Will that kill me? No. Will I starve to death? Nope. So what am I afraid of?

He goes on kneading.

‘It’s not enough for me. The piano isn’t enough for me either, I’m constantly playing pieces that are really too big for the piano. Just wait there for a second, I’ve got to go to the toilet.’

He leaves his phone on the table, and his glasses too. Outside it starts snowing, thin, ugly and relentless. It’s nearly midday and not really light.

‘Let’s have a go’, he says when he comes back. What? ‘The book. Let’s do it. Except I can’t really say what I’ll be doing in a few months.’

All set.

Right: shouldn’t we be on first-name terms?

‘Sure’, Igor says, ‘I’m Igor.’

Then he looks at his phone, and says by way of farewell, ‘Right, I’m off to bed.’

#

The journey itself starts before that.

Wednesday, 18 September 2019. Igor steps onto the stage in the grand hall of the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. On the programme: three Beethoven sonatas and then a fourth, No. 21 in C major Opus 53, the Waldstein Sonata. Igor calls it ‘the most life-affirming piece of music I know.’

The hall is in darkness, Igor sits in the beam of three spotlights shining directly down on him from above. It was the author Roger Willemsen who said that happiness is rarely to be found in a pure C major chord, but the Waldstein Sonata is one of the exceptions, because it begins with fourteen pure C major chords, allegro con brio. They feel like a pleasant shower of rain, like unease at the start of something, butterflies in your stomach before you get going. Like pure happiness.

In the hands of many other pianists, the Waldstein Sonata sounds like a hurdle race where the only thing that counts is following all the instructions as precisely as possible and not stumbling. You can hear the rules through the music. Igor, on the other hand, sets the music free. He plunges into the first movement at such a breakneck tempo that you’re afraid it’s going to send him flying off course. The movement is composed speed, a pounding heart, vibration. So many notes, so many individual sounds in a single sonata movement is rare. You can feel the tempo. Only once does Beethoven allow the music to get slower. If you ask him why he plays so fast, Igor says simply: Because I can. And because it’s what Beethoven demands.

In the second movement the music pauses, the lightness has made way for melancholy. Igor sets the chords down so that all the notes stand motionless like columns in space; the music sounds as if it was written not by Beethoven, but by the very old Franz Liszt: every note comes straight from eternity. There is no hint of a melody striving to get somewhere. The notes are a physical state; nothing moves. Everything is what it is.

The music sounds three-dimensional. But not because it’s coming from different directions: the work itself is three-dimensional. The harmonies create planes and pillars, spaces and doors to the next room. There is light and darkness, there is colour and temperature – and then a voice comes into the room.

Igor isn’t the kind of musician to retreat behind the work. He says: I’m playing this, I make the rules. Not only is he not shy of saying ‘I’ – he’s saying it’s the only way.

But it will still be a while before he finds out who he means when he says ‘I’.

And then, in the middle of the night, the sun comes up again. Igor summons a melody and chases it through the sound traditions of different eras, even those that come after Beethoven. You can hear Liszt and Rachmaninov, Debussy and Glass, and soon the music also gets a beat – are you allowed to play it like that? Why not, Igor says. Without the pianist the piece wouldn’t even exist now. The finale starts small, gets bigger and ends up cosmic, a melody gives rise to a world, and in the end everything ends in pure euphoria.

Igor, on the stage in the Elbphilharmonie, takes a bow.

Plays an encore.

Which piece is unimportant.

On the way home the music still echoes, as it often does after concerts, but this time each note seems to have left a small footprint and the notes as a whole a big one.

What, if you’ll excuse me, was that?

From whose life was Igor telling stories? From his own? Or the audience’s?

Where do the colours come from, the nuances, the power?

Why does the Waldstein Sonata, that piece of music that’s a good 200 years old, so often sound merely exhausted, overplayed, competent? And today so natural – no, so self-evident, as if it couldn’t be otherwise, as if Ludwig van Beethoven hadn’t at some point written it all down, but as if it had always been there and had just become audible for the first time.

Might that be the whole mystery? Does Igor sound as interesting as he does because he doesn’t just play a piece of music, but at the same time – with complete commitment, and a complete sense of risk – brings himself on stage?

Because this is unambiguously not about C major, four-four time, allegro con brio, main subject, second subject. This is about much more than that. If it didn’t sound so platitudinous and pompous you might say: it’s about everything.

And if the reflection of life in the music is so exciting: what must life itself be like?

Or is all the tension, all the power, in the music, and everything else is bleak and empty?

What would be left if you took piano playing away from someone who plays piano like that? Would it even be possible?

How does someone who plays like that come to terms with himself?

#

So this is the story. Igor Levit, 32, not fully stretched by being the pianist of the century and at the same time being completely exhausted by it. In search of an answer to the question and for months in search of the question itself: who am I and what am I supposed to be doing?

And now?

Usually biographies consist of an uninterrupted narrative of events in a life which create the impression that the life described is a sequence of causalities which feel just as logical and conclusive at the moment when they are experienced as they do in retrospect. It is the attempt to give a meaning to things, and some things only acquire a meaning in context.

But life doesn’t consist only of events, but also of feelings, intimations, urgency, tedium, insecurity, good and bad luck. And above all of more questions than answers.

Such a book also never consists of the absolute truth, but only ever personal truth. Stories that are told over and over and that have got better with each telling, in which narrators can barely agree on time and place, they only agree that everything happened exactly like that.

One possibility would be to begin at the beginning, or, even better, before the beginning. Then one would have to tell the story of how in the late winter of 1987 Elena Levit walked to the conservatoire in Gorki morning after morning, and home again evening after evening, to the tiny flat in one of the low-rise estates, and how she always talked to Igor in her belly, even though she still had no idea that the child she was pregnant with was going to be a boy.

And one would also have to tell the story of how, before Igor was born, she dreamt she was sitting at a concert, and on the stage her son was playing Piano Concerto No. 2 Opus 18 in C minor by Sergei Rachmaninov. And 15 years later, in the Maria Callas Competition in Athens, Elena Levit really is sitting in a concert hall while on the podium her son really is playing Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 Opus 18 in C minor.

Stories like that. But do they help?

To understand why a pianist plays as he plays, thinks as he thinks and feels as he feels, do you need to start before the first note? Particularly when he himself can’t even remember that first note?

That might be true of lots of others, but it doesn’t apply to Igor. Igor Levit can only be understood in the context of the immediate present.

There’s also a very different problem with the past – but more of that later.

So we decide to focus on a little bit of present for the book. On that day in December there’s a lot to indicate that the coming year would be a suitable period of time. Because it is largely planned and easy to grasp.

Igor’s concert dates have been arranged for the whole year. It’s the year of the celebration of the 250th anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven’s birth. Igor is one of the most in-demand Beethoven interpreters on the market, so there’s a lot going on. In early February he’s supposed to moderate an edition of the ZDF culture magazine programme Aspekte. On 10 March, his thirty-third birthday, he’s giving a concert with two Beethoven piano concertos in the Elbphilharmonie. In May he’s playing a tour of the USA, with his solo debut at the Carnegie Hall in New York. Then, in August: three weeks of the Salzburg Festival, with the Beethoven sonatas.

So far, so good.

We agree to meet up in Salzburg; three weeks seem like a good framework for discussions about the book. Enough time to go into it in depth. We’d see what’s happened by then.

We knew no better.

Most of the things that this book considers were unimaginable on that day in December. But it doesn’t matter.

When you’re telling a joke it’s important to know the last sentence when you start the first one. This book is not a joke.

#

The simplest option for telling the story of Igor’s life is at the same time the best known and the most impressive: Igor’s success story.

Born in 1987 in Nizhni Novgorod, a city in the Soviet Union that was still called Gorki at the time. Moves to Germany at the age of eight, first to Dortmund, then Hanover. Studies at Hanover University of Music, Drama and Media. Graduates with the highest marks ever awarded by the institution. His debut CD of Beethoven’s last five sonatas wins BBC Music Magazine’s Newcomer Prize and the Young Artist Prize of the Royal Philharmonic Society. This is followed by a recording of the partitas of Johann Sebastian Bach, an album with the set of variations on ‘The People United Will Never Be Defeated!’ by Frederic Rzewski as well as the Goldberg and Diabelli Variations. The album of variations wins Recording of the Year at the Gramophone 2016 Classical Music Awards. His complete recording of the Beethoven piano sonatas tops the classical music charts. He gives solo performances at the Salzburg Festival, at the Lucerne Festival, at the Elbphilharmonie, at London’s Wigmore Hall, at the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the Vienna Musikverein and New York’s Carnegie Hall. Apart from all that, he guests with internationally leading orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic.

He is a holder of the 2018 Gilmore Artist Award and 2018 Instrumentalist of the Year of the Royal Philharmonic Society. In the spring of 2019, Hanover University of Music gave him a professorship. For his political commitment he was awarded the 5th International Beethoven Prize in 2019, followed in 2020 by the Statue ‘B’ of the International Auschwitz Committee.

This biography is printed in the programmes for Igor’s concerts, in the booklets for his CDs, on his website. Nothing here is exaggerated; every word is true. But, and in common with every other artist’s biography: these words don’t relate, explain or substantiate anything. They contain only the results, but not the journey there. Only the highs, none of the lows.

#

Obvious things first: Igor is a pianist. That in itself explains a lot.

A pianist lives by playing in front of an audience. He masters performances. He lives for them.

Performances without an audience are possible, but pointless; music not only needs someone to make it but also someone to hear it. A pianist needs an audience, he needs a counterpart, he isn’t self-sufficient.

Not least because he has spent by far the largest part of his life alone with music.

From early childhood onwards pianists spend a very great deal of time alone with themselves at the instrument, in the practice room, on tours, on stage. Which doesn’t necessarily mean that pianists are lonely; that only happens when they can’t be alone in a good way.

Their life is played out in notes; they learn to mould them so that they can be anything: love, pain, longing, courage. And if they have put enough of themselves into the notes, their listeners find themselves in them too.

‘I play my music with my biography, my experiences and thoughts on this particular day’, Igor once said in an interview with Der Tagesspiegel. ‘And the audience hears the music exactly the same, in their own way. It’s a hugely intimate process. If I ever lose the utopia of the audience interpreting along with me on equal terms, I’ll hang up my hat as a pianist.’

Pianists learn early on to be self-reliant. They can focus on a single subject for a very long time. They are accustomed, in every concert, in every recording, throughout the whole of their career, to carrying all ultimate responsibility on their own shoulders.

But that’s not all. Igor can only lead the life he leads because he performs effectively. He can only perform effectively if he is disciplined. He lives in a system of rules and laws, most of them unwritten. And these rules are no different from any rules in music: you’re allowed to break them at your own risk. But before you break them, you have to know what they are.

Playing the piano isn’t hard, at least in terms of the fundamental principles. You press down a key and hear a note. And you immediately hear how different a note can sound according to how much power you put into striking the key.

That’s exactly where it starts getting hard.

On a violin it’s three years before you achieve the first note, and wind instruments are complicated too.

That’s why the piano is so good for children. Each note is a success; music immediately sounds like music.

When asked why he actually plays the piano, Igor says: because he can’t play any other instrument.

‘The simplest explanation is probably: because I started at the age of three and have never stopped. I crawled to the piano all by myself, I can’t remember doing it.’

Sometimes as an encore Igor plays a miniature by Dmitri Shostakovich – a scherzo, Opus 90b, the first part of the Dancing Dolls, a piano suite from 1952. ‘My mother always used to play this waltz with her pupils. I heard it as a young child.’ The right hand plays a simple melody in three-four time, the left a simple accompaniment. A piece more for two fingers than two hands, any piano pupil could play it with a bit of practice.

The beginning, at least. After the middle part the melody stays in three-four time, while the accompaniment switches to four-four, and for sixteen bars the two run along in parallel, while the audience’s synapses tie themselves up in knots. When playing too.

Too much is happening at the same time.

At least according to the criteria of people who aren’t Igor. Too much at the same time has never been a category for Igor.

#

One of the crucial evenings in Igor’s career is 17 September 2004, a Friday. Igor, 17 years old, performs in the Piano Olympics in Bad Kissingen. A competition that is only open to participants who have already won prizes elsewhere. Other performers include: Martin Stadtfeld, who by this time already has a recording contract with Sony Music, and Alice Sara Ott, whom Igor knows from Salzburg, from the summer academies of his teacher Karl-Heinz Kämmerling. Igor plays Schumann, Beethoven and the Bach transcriptions of Max Reger, an unusual programme for a competition.

And he makes the acquaintance of probably two of the most powerful women in the German music business: Eleonore Büning, music critic of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and Kari Kahl-Wolfsjäger who, before founding the competition, established the KunstFest Weimar, runs the Beethoven Festival in Bonn and in 1986 came up with the Kissinger Summer, three not insignificant festivals in the German-speaking world.

He takes second prize. Like all prize-winners he’s allowed to play in the Kissinger Summer the following year and, as part of the deal, also gets a series of other performance opportunities: for musicians a chance to collect routines, for the organizers of the competition the opportunity to write off their expenses.

Then a lot of time passes.

Early in 2010 Kari Kahl-Wolfsjäger called Igor and asked if he would like to join her on a trip to China. There was a cultural exchange between the Chinese province of Shandong and the state of Bavaria, which was sending a selection of young artists to China for International Music Week: several pianists, several violinists, some singers, for seven concerts over twelve days, in various configurations. Igor agreed. By now he was about to sit for his concert diploma, but otherwise he hadn’t got much on his plate. He discussed two or three possible programmes and booked the fights to Beijing.

Igor travelled a day ahead, because he wanted to eat Peking duck, and some other musicians from the group flew out in advance as well. After landing, he saw an announcement on the monitors at the airport that the volcano Eyjafjallajökull had erupted in Iceland. A few hours later, because of ash at high altitudes, the whole of Russian airspace was closed. Air traffic was suspended across large parts of Europe, and a lot of his colleagues were stuck in Germany; the only pianist in the group who made it to China was Igor.

‘Then, with giddy recklessness, I said: I’ll take on all the concerts, what’s the problem? In cities with a million people and no proper concert halls, it was quite an adventurous idea. I just played three times as many. I also had to dig out a whole lot of repertoire because we sometimes put on two concerts in one city – and I couldn’t play the same thing twice.’

Igor played chamber music, accompanied Lieder evenings and violin sonatas, and also took over his colleagues’ piano recitals.

‘He knew all the works, and if he didn’t, he’d learned them within a day’, the music critic Eleonore Büning says in a radio interview with WDR. She was also in China – Büning had been with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra on a tour of Asia and wished she was back at home. But now she couldn’t get away – and visited her old friend Kari Kahl-Wolfsjäger, who was rehearsing in Jinan with her troupe.

The conditions weren’t ideal. On the stage of the conference centre in Jinan there was a grand piano that sounded as if it had been left in the garden all winter. Igor accompanied Mozart violin sonatas and Schubert Lieder, and finished with the Waldstein Sonata.

Eleonore Büning came into the hall in the middle of the rehearsal, listened for a while and wondered: what kind of pianist is this?

She thought she knew him from somewhere, but couldn’t place him.

The last time she heard him he was 17 years old and podgy.

Four days later, in an unheated and dirty concert hall in Qingdao, with amplifying equipment that gave off a mezzoforte buzz, there was an out-of-tune Baldwin grand piano, with a broken A flat above middle C. When you struck the key, a lot of other notes sounded, but not the A flat. The B rattled too.

The hastily summoned piano tuner didn’t appear. Levit changed the programme: he didn’t play Waldstein, but instead seven of the twelve Transcendental Études by Liszt, which he learned a long time ago but had never played in public. ‘The most sacred passage in Waldstein is the bit in the minor key in the second movement with the diminished fifth, and for that I need the A flat’, Igor explained to the flummoxed critic. ‘That was impossible on this piano, I knew that. I didn’t know what would happen with Liszt. It was an experiment.’ The experiment was successful.

On the four evenings that follow, apart from Waldstein and Liszt, Igor plays Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 Opus 73 in E flat major and Schubert’s Moments musicaux. He accompanied Beethoven violin sonatas and Lieder recitals. A bravura performance.

On the bus journey from Jinan to Qingdao, Eleonore Büning watched Levit practising the piano concerto: score on his knees, keyboard in his head, an Alfred Brendel recording in his ears.

‘First of all I always learn a new piece from the score without a piano. I carry it around with me in my head, and sometimes it goes on for ages, months. You have to know it before you play it. Then when I sit down and play it for the first time it isn’t the first time.’ Levit said this not on the bus in China, but at home on the phone when Eleonore Büning told him she wanted to write a profile of him and had two more questions. He was in the student canteen when she called.

A profile in the Frankfurter Allgemeine of a pianist who hadn’t even sat his concert exams, and hasn’t made a CD apart from a recording of the Diabelli Variations, is unusual.

‘He wasn’t even on the public radar’, Büning would say on WDR. ‘But I was – and still am – so convinced of his artistic integrity. I’m not talking about his technical skill, a lot of people have that, and technically he’s unimpeachable. But the expressive power, the intensity, the creativity of this musician – I’d never experienced anything like it in the whole of my career.’ She decided to tell the world.

The article was published on 3 May 2010, and didn’t begin very flatteringly.

‘Six years ago I heard Igor Levit for the first time. He was 17, a round little person and incredibly chatty. He poked his nose in everywhere, told unfunny jokes, had something to say about every subject, and it was only when he was sitting at the piano and playing that this fat child temporarily stopped talking.’

But then.

‘What distinguishes great pianists? That they flawlessly master the most difficult literature. But above all: that they know something about life, and how it is reflected and elevated through the development and structure, the history and message of the music: so that they can open up the pieces they play the way you open a book and read it, and that they tell us their stories as if they had just happened for the first time, so that we understand it all easily, with our ears and our hearts.’

The article is one of those ones that music critics only get to write a few times in their lives and only when they can’t quite believe what they are hearing. ‘With Levit, music comes into being in his head, not on the keys’, Eleonore Büning wrote. ‘In most rising young pianists, even the very gifted ones, it’s exactly the other way around.’

She concluded with a sentence that would linger in Igor’s mind for a long time to come.

‘So the people of Bad Kissingen can retrospectively pat themselves on the back and say: a great year. But Igor Levit, unlike … all the other nice compliant attractive, mechanical reelers-off of notes that the PR machine throws up from time to time, has what it takes to become one of the great pianists of the century. Or rather, he is already.’

Igor knew that the profile had been published, but not how important it would be. He saw the paper at a filling station near his parents’ house, and asked the man at the till if he could take a look inside. Then he bought the whole stack.

The whole industry read the article. His future press agent Maren Borchers. And the man who gave him the contract with his record company. On that Sunday, in May 2010, a new chapter began.

#

When Maren Borchers finished reading Eleonore Büning’s article, she called her up and shouted at her down the phone. How can you write a piece like that? she asked. How can you lay such a burden on somebody? How can you set the bar so high? He’s still a baby, he can only lose.

Eleonore Büning replied that she knew all that – but you only get to write such a piece once in your life, and this was it.

Months later, in January 2011, Eleonore Büning had her Bechstein grand refurbished – and invited Igor to give a house concert in the sitting room of her flat in an old building in Berlin. It was her birthday, and she had invited Berlin artists, fellow arts journalists, important contacts, friends and Maren Borchers.

Borchers’ husband came with her. She had to promise him not to spend all evening working as she usually did on such evenings.

When they turned up, Büning took Igor and Maren Borchers by the hands, led them into the music library and closed the door from outside, saying: you two need to talk.

Borchers knew Igor only from Büning’s article, and had never heard him play. Igor knew her from an interview of which he remembered only the headline: ‘I don’t take on prodigies.’

They talked briefly, about this and that.

Then Igor had to play. Beethoven, the ‘Tempest’. Eleonore Büning wept with happiness. After the concert Igor and Borchers arranged to meet for a coffee in the Literaturhaus. When they met she said: ‘We don’t have to work together. We can, if we want. But we don’t have to.’ Her words made an impression.

This was the day when Igor’s collaboration with his press agent began. A woman who says that, without her, Igor wouldn’t have become who he is today.

That’s exactly how Igor sees things too.

‘I haven’t got that many human constants in my life’, Igor says, ‘and I’m not really after constants. But if they show up of their own accord, I’m not going to let go of them. Maren is a constant, and she will remain one. I’m not giving her up.’

Maren Borchers spent the first two years turning down requests for interviews. There wasn’t yet anything worth advertising.

When she set up a Facebook page for her agency, she suggested to Igor: do a public rehearsal in the Maison de France. We’ll invite people via Facebook and see what happens.

No one came.

The articles published about Igor were divided into two camps.

There were colleagues who disagreed with Eleonore Büning. And there were those who were enthusiastic about Igor, tried and tested critics as well as authors who didn’t usually write about classical music.

After this Igor became increasingly noisy on Twitter, and the twin soundtracks ran in parallel.

Maren Borchers’ operating principle: the artist should be able to concentrate on art. He needs a milieu that makes that possible for him – a milieu that he blindly trusts.

Except that Igor’s intention wasn’t to concentrate solely on his art.

#

It’s not the result of a strategy that Igor is as visible a presence away from the concert hall as he is in it.

But neither is it completely unplanned.

Maren Borchers tried to get him to focus. Igor did a lot of what he did because Borchers had orchestrated it. He did a lot more because Borchers couldn’t stop him. Igor’s strategy was one of maximum concentration – except on lots of things at the same time.

‘Things are the way they are today not least because of how we worked’, Maren Borchers says. ‘If we’d passed Igor around the talk shows like ripe fruit from the get-go, we wouldn’t be where we are now.’ Not any more.

Before founding her agency Borchers had worked for a classical music label and met a tenor who very quickly became successful. He asked her to advise him, told her she was the only person in the field that he trusted. She warned him: do less. Less. Even less. Don’t go on that TV show, don’t go on that one, don’t go on the glitzy late-night chat show – leave that for now, just wait! But it wasn’t going fast enough for him. She gave him advice, he ignored her warnings and eventually she said: Fine, you’ve decided to burn the candles at both ends. His career didn’t last. She wasn’t going to let that happen again.

It was imperative that Igor didn’t spread himself too thinly. He was too much anyway.